I. Introduction

In this case the plaintiff trustees, Richard H. Pearson and Bonnie B. Pearson [Note 1] (together, the Pearsons), claim passage rights over Bayberry Road, a private way in Wareham, Massachusetts. The defendant, Bayview Associates, Inc. (Bayview), says it owns the fee in Bayberry Road, and that the plaintiffs do not. The plaintiffs seek to use Bayberry Road to gain access to the parcel they currently own, which has a street address of 5B Bayberry Road. The plaintiffs base their claimed right, in relevant part, on an easement established in a 1927 deed. The plaintiffs contend that this record easement runs the route of Bayberry Road and that plaintiffs hold, under the 1927 easement, the right to travel along Bayberry Road to come in and out of the plaintiffs lot at 5B Bayberry Road. The defendant denies that the 1927 easement lies along this route, saying that the 1927 easement's location does not touch the land the plaintiffs own today.

Members of the Pearson family have owned land in this neighborhood since 1953. Until 1999, the Pearson land was larger; the Pearson parcel included both the land still owned by the plaintiffs, at 5B Bayberry Road, and an adjoining lot, which has a street address of 5A Bayberry Road. In 1999, the Pearsons sold off the improved 5A Bayberry Road parcel to third parties. The Pearsons did not reserve--for the benefit of the land they kept--any record right of passage across the lot they conveyed away. This litigation seeks to establish that the land the plaintiff trustees still own is not landlocked following the 1999 sale. Plaintiffs ask the court to determine that their retained land enjoys a right of way, not across the parcel sold off, but over Bayberry Road. Currently before the court is the question whether the plaintiffs have rights to use Bayberry Road pursuant to the 1927 easement. The court, following trial, is called upon to determine the location on the ground of the easement created in 1927, and, in particular, to decide if that easement reaches the plaintiffs parcel at 5B Bayberry Road.

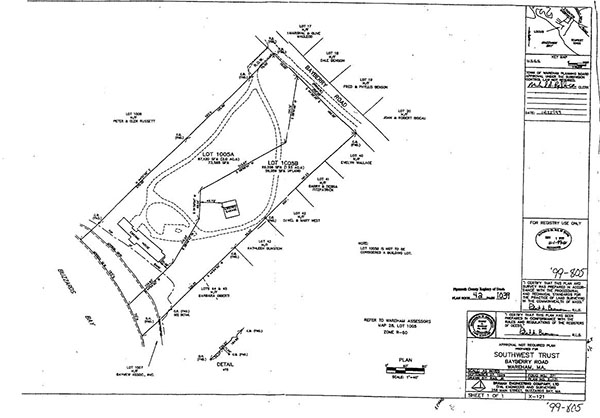

Before the 1999 sale, the Pearson family owned one parcel (locus) of a bit less than four acres. The locus, the same land the Pearson interests owned since 1953, is the land shown as Lot 1005A and Lot 1005B on a 1999 approval not required division plan recorded with the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds (Registry) in Plan Book 42, Page 1039. A copy of this 1999 plan, which is agreed Exhibit 27, is appended to this decision. As the plan reveals, both lots are waterfront, and run on one side along Buzzards Bay. In 1999, the Pearsons sold Lot 1005A for $1,100,000 to Barry Rose, Katherine Rose and Kay Goldstein. These buyers (Lot 1005A

owners) are not parties to this litigation.

After the 1999 conveyance out of Lot 1005A, the Pearson trustees still owned Lot 1005B, about 1.53 acres in area, of which 59,059 square feet were upland. On the boundary opposite the waterfront, Lot 1005B is shown as bounding on Bayberry Road a distance of 180.20 feet. Lot 1005A is shown on the recorded 1999 plan as having a 70.00 foot long boundary along Bayberry Road. It generally is without dispute that the locus prior to the 1999 sale enjoyed in some manner the benefit of the apparent easement granted in 1927, which put in place a right of way suitable for the Grantees purposes from a point at the Northeasterly side of the lot hereby conveyed to ... Beach Road. The location on the ground of the right of way which that deed established is the central issue at this phase of this case.

At the time of the 1999 sale of Lot 1005A, the plan used in the conveyance showed a pre- existing right of way running away from Bayberry Road, perpendicular to it, in the direction of the water, a distance of approximately 75 feet over land of others before turning into Lot 1005A. This right of way runs for this stretch through the neighboring property (Russett lot) [Note 2] and connects Lot 1005A with Bayberry Road where it fronts on the Russett lot nearest to Lot 1005A. After this short 75-foot right of way enters Lot 1005A, it is shown as connecting with internal paths or drives over the locus, indicated on the 1999 plan by a series of looping dashed lines.

Although these internal routes appear to depict connections across the new zig-zag boundary separating Lot 1005A from Lot 1005B, the Pearsons, who retained title to lot 1005B, did not reserve for themselves any easement for passage over lot 1005A. As a matter of record title at least, Lot 1005B has no express rights across Lot 1005A, and is landlocked unless the Pearsons hold rights to use Bayberry Road to pass from Lot 1005B to reach the public way to which the private Bayberry Road connects, now known as Little Harbor Road. [Note 3] (The parties agree that in 1927 what now is called Little Harbor Road was Beach Road.) In 2001, Bayview erected a fence along Bayberry Road, physically blocking passage across Lot 1005Bs property line at Bayberry Road.

The Pearsons claim that the right of way included in the original 1927 deed conveying the locus granted a right to use the entirety of Bayberry Road for any purpose, including the right to travel along Bayberry Road to access lot 1005B. Bayview contends that the access routed through the Russett lot, which currently only benefits lot 1005A, [Note 4] is the original, or the implicitly relocated, right of way, and the 1999 division of the locus left lot 1005B with no record way out. Alternatively, Bayview (again disputing the Pearsons interpretation of where the 1927 deed locates the right of way), claims that, even if that right of way went beyond what is now the Russett land, and passed over what is now Bayberry Road along its boundary with the locus, the granted 1927 easement only connected with the locus very near its northwest cornerthe one farthest to the north and west. Bayview says that the court cannot find that the 1927 easement extends far enough along Bayberry Road to reach what is now the Pearsons Lot 1005B.

II. Procedural History

The Pearsons filed a complaint on March 26, 2012 containing the following three counts:

1. Count One: Quiet Title;

2. Count Two: Trespass; and

3. Count Three: Assessment of costs, pursuant to G.L. c. 187, § 4.

The court held a case management conference on May 11, 2012, following which the court directed discovery to conclude by October 31, 2012 and dispositive motions to be filed by November 30, 2012. No motion for summary judgment was filed by either party prior to the deadline established by the court, but the plaintiffs filed a request to extend discovery until November 30, 2012, which was allowed. [Note 5] There was more than one change in counsel for the plaintiffs, but their current counsel appeared in June of 2013.

On September 30, 2014, the parties filed a joint motion to extend time for filing motions for summary judgment. The motion was denied in a docket entry dated October 8, 2014:

Result: Hearing Held on Joint Motion to Extend Time for Filing Motions for Summary Judgment. Attorney Evans Huber Appeared for Plaintiff. Counsel for Defendant Elected Not to Appear. Motion DENIED. Deadline for Filing Dispositive Motions, Originally Set for November 30, 2012, and Extended to December 31, 2012, Has Too Long Passed. Additionally, the Plaintiff's Proposed Motion Is Unlikely to Dispose of All Issues in this Case, and Trial Likely Will Be Required Even Were Court to Permit Parties to Engage in Motion Practice at this Late Stage. Pretrial Conference Scheduled November 18, 2014 at 3:30 P.M. Parties to Hold December 19, 2014 at 9:30 A.M. for Trial at the Land Court in Boston. To the Extent Parties Are Able to Agree That Some or All Issues in this Case May Be Decided by Court Without Live Testimony, Parties May, in Their Joint Pretrial Memorandum to Be Filed with Court, Propose Submitting Case to Court on Agreed Record or Case Stated.

On November 18, 2014, counsel attended a pretrial conference where they stipulated to limiting the scope of trial to the threshold (and potentially dispositive) issue of locating the record easement created in 1927. With counsels concurrence, the court instructed them to offer evidence limited to documents and testimony by experts on [the] issue of determining [the] location of [the] 1927 easement. The plaintiffs claims for a prescriptive easement, or other theories of nonrecord rights or rights acquired by use, were to be held in abeyance pending resolution by the court of the record easements location.

Trial began on January 21, 2015. Thirty-seven exhibits were admitted into evidence and three witnesses testified: called by the plaintiffs were Mr. Robert Braman, a registered land surveyor; and a real estate attorney, Richard Golder; the defendant called another real estate lawyer, Richard Gallivan. The crux of the plaintiffs argument was that the 1927 deed conveying the Locus included a right of way on Bayberry Road, and that the right of way as granted provides for access at any and every point on Bayberry Road. [Note 6] The defendant argued that the pre- existing right of way onto lot 1005A, extending from just beyond Lot 1005As northwestern corner through the Russett lot, is the route of the original right of way granted by the 1927 deed.

Two court reporters, Wendy L. Thomas and Karen Smith, were sworn and present to create transcripts of the testimony and the two days of trial proceedings. When the taking of evidence concluded, the court suspended the trial. Counsel were instructed to file and serve posttrial legal memoranda, proposed findings of fact, and rulings of law upon receipt of the trial transcript. The transcript was received in March, and posttrial written submissions were submitted to the court in April. Counsel then returned to the court, made closing arguments, the transcript of them was received and filed, and the case taken under advisement. I now decide where the 1927 deed located the easement, and whether the location of that record right of way allows access directly from Bayberry Road to plaintiffs lot 1005B.

III. Findings of Fact

Based on the evidence as I credit it and find it to be persuasive, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, in addition to the facts set forth elsewhere in this decision, I make the following factual findings:

1. The locus in this case was, until 1999, one roughly four-acre lot located at 1005 Bayberry Road, Wareham, Massachusetts, 02571.

2. The plaintiffs, Richard Pearson and Bonnie Pearson, as trustees, owned the locus prior to 1999.

3. In 1999, pursuant to endorsement of a so-called approval not required plan under G.L. c. 41 § 81P, recorded in the Registry at Plan Book 42, Page 1039, the Pearsons divided the locus into lot 1005A (the western portion of the locus) and lot 1005B (the eastern portion of the locus).

4. The Pearsons conveyed lot 1005A to unrelated parties for value in 1999 by deed recorded in the Registry at Book 18004, Page 303, but the grantors retained title to lot 1005B.

5. The defendant, Bayview Associates, Inc., is a homeowners association comprised of approximately twenty homeowners with improved lots located on or near Bayberry Road.

6. Bayview claims to own the fee title in Bayberry Road and maintains it as a private right of way. Nothing in the evidence suggests there are any general public rights to use Bayberry Road.

7. Bayberry Road first appeared on a recorded plan as such on the Plot Plan Subdivision 3 of Land Situated in Wareham, Mass. at Little Harbor Owned by Charles Jacoby, Surveyed by Ernest A. Truran, C.E." dated October, 1946 and recorded that year at the Registry in Plan Book 7, Page 94.

8. In and prior to 1927, William L. Carlton owned a substantial amount of land in Wareham, Massachusetts, including the locus and the land surrounding present-day Bayberry Road.

9. By deed dated February 10, 1927, recorded in the Registry at Book 1549, Page 380, Carlton conveyed the locus to Frank H. Godfrey. This is the first conveyance of the locus, and is the root of the easement at issue in this case.

10. Frank H. Godfrey and his wife Anna T. Godfrey conveyed the locus in a July 29, 1953 deed to Ellen A. Messenger, recorded in the Registry at Book 2288, Page 178.

11. Ellen A. Messenger then conveyed the locus in an October 10, 1953 deed to Nathan Pearson, recorded in the Registry at Book 2304, Page 469. This deed, the first putting title into the Pearson family interests, reduced the width of the locus by twenty feet, but the parties agree that this change is immaterial to this case. The metes and bounds description of the locus did not change in any subsequent conveyances.

12. Nathan Pearson then conveyed the locus in a 1978 deed to Richard H. Pearson, as trustee of the Warebrook Realty Trust, recorded in the Registry at Book 4519, Page 334.

13. Richard H. Pearson as Trustee of the same trust then conveyed the locus in a May 22, 1990 deed to Richard Pearson, as trustee of the Southwest Trust, recorded in the Registry at Book 9767, Page 196.

14. The 1927 Carlton to Godfrey deed conveyed, along with the fee to the locus, among other rights not here relevant, also a right of way suitable for the Grantees purposes from a point at the Northeasterly side of the lot hereby conveyed to said Beach Road. This is the language whose meaning and effect is in dispute.

15. Beach Road as used in the 1927 deed today is known as Little Harbor Road.

16. The same 1927 language establishing the disputed right of way carries forward in each of the subsequent deeds conveying the locus.

17. The 1927 Carlton to Godfrey deed references a plan (1927 Titus Plan) titled Plan of land in Wareham, Mass. , owned by Mrs. Henry M. Channing, prepared by John E. Titus, Landscape Architect, dated July 9, 1926, and revised February 7, 1927. This deed refers to this Titus Plan to describe further the locus, which in the deed, after being laid out by metes and bounds, is then described as [b]eing the parcel of land marked 4 Acres on the Titus Plan.

18. The 1927 Titus Plan never was recorded and has not been located, despite reasonable and diligent efforts by both parties. It is the absence of this plan, referred to in the seminal 1927 deed but evidently not presented for record with the deed or at any time, that has given rise to the challenging issue of where the parties to the deed creating the 1927 easement intended it to go. I infer that this missing unrecorded plan, prepared not long before the 1927 deed and referenced in it, quite likely supplied the answer to the central question that has kept the parties to the current litigation in dispute.

19. By deed dated January 6, 1928, recorded in Book 1553, Page 53, Carlton conveyed to Robert F. Herrick all of Carltons remaining land surrounding the locus, except one 5.8 acre beachfront lot, which was adjacent to the southeast side of the locus, and which Carlton kept for himself.

20. In the Carlton to Herrick deed, Carlton reserved for the benefit of himself, his heirs and assigns, for the benefit of his remaining land, a right-of-way suitable for Grantors purposes, from the Northeasterly boundary of the Grantors remaining land to the Beach Road, so-called . . .

21. In 1942, Robert Herrick left all of the land he had acquired from Carlton to the Massachusetts General Hospital.

22. By deed dated February 23, 1944, recorded in Book 1859, Page 361, the Massachusetts General Hospital conveyed the property to Charles W. and Barbara I. Jacoby.

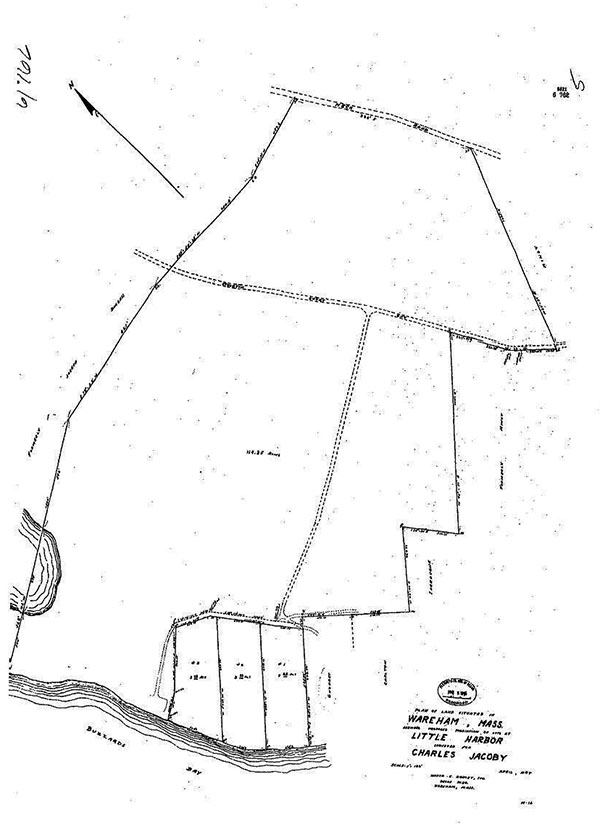

23. Jacoby commissioned a survey, which was prepared by surveyor Walter E. Rowley, in 1944 (Rowley Plan). The Rowley Plan, dated April, 1944, is on record in the Registry at Plan Book 6, Page 762. It is agreed Exhibit 8. On it, our locus is shown in a general way, though not with a complete perimeter, as Godfrey, its then owner. A copy of a version of the Rowley Plan is appended to this decision.

24. The Rowley Plan shows, by means of dashed lines, the routes of two ways which might have provided points of access from the locus to be used to reach Beach Road: one from what is now Bayberry Road, and following its route today, and another (Russett right of way.) a short distance to the south and west of the northwest corner of the locus, extending through what is now the Russett lot before entering into the locus.

25. In 1995, the Russetts recorded an instrument which purported to relocate an easement over the Russett lot benefiting the locus. In this document the Russetts granted a right of way for the benefit of the Pearsons to pass and repass by foot or motor vehicle over the Driveway Easement area. The relocation document, dated and recorded June 2, 1995 is in the Registry at Book 13612, Page 123.

26. The 1995 relocation document, captioned Easement, purports to terminate the prior access via the Previous R.O.W. shown on a May 4, 1995 plan recorded with the 1995 recorded document, and to provide in lieu of the previous right of way a new access, over an area of 1,370 square feet shown on the accompanying plan as Driveway Easement. The document says [s]aid grant being appurtenant to and being granted to provide access to the existing two family dwelling of the grantee at Bayberry Road.... The document provides that the former right of of [sic] way is being terminated by the recordation of this instrument, the layout of said driveway easement on the plan to be recorded herewith and by the construction heretofore of physical access from Bayberry Road to the land of grantee by the grantors. Although there is nothing in this relocation document to show that it was executed by the grantee, Bonnie B. Pearson as Trustee of the Southwest Trust, I find it reasonable to conclude that the Pearson interests accepted this document and its terms, causing it to be recorded, and thereby agreeing to the relocation of the route of the driveway easement and to the relinquishment of rights to pass over the former route, which the document said were to be terminated. This had the effect of discontinuing any preexisting right of the locus owner to pass more perpendicularly across the Russett land from the Bayberry Road intersection to reach Lot 1005. This document also establishes that the purpose of this new or relocated easement was to provide access going forward only in this new 1,370 square foot area on the Russett lot, hugging the Pearson property line, and that the purpose of that access was to serve the then existing two-family residence on the Pearson property.

27. In November of 2001, Bayview erected a split rail fence along Bayberry Road. The fence prevents direct access from Bayberry Road to Lot 1005B.

28. The Pearsons filed this case against Bayview on March 26, 2012, alleging that the right of way conveyed by the 1927 deed allows unlimited ingress and egress over Bayberry Road for the benefit of lot 1005B.

29. Mr. Robert Braman is a registered land surveyor with Braman Survey & Associates, LLC.

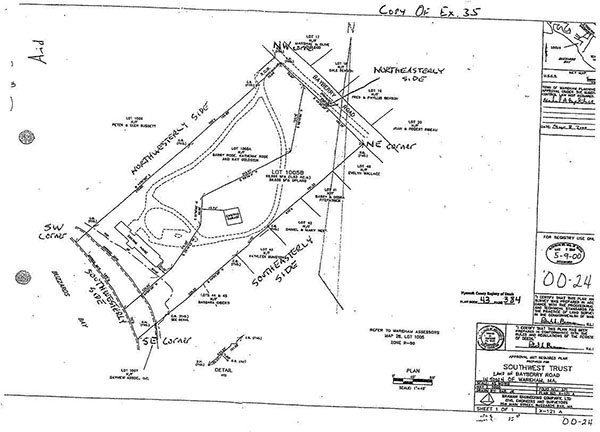

30. At trial, Mr. Braman used a plan of the locus to mark its northwest, northeast, southwest, and southeast sides. What he marked is Exhibit 35. The 1927 Carlton- Godfrey deed describes the boundaries of the locus in terms of the southeast, northeast, northwest, and northeast corners of the lot. Mr. Braman testified convincingly that the side of the locus abutting Bayberry Road would be referred to as the northeastern side, rather than the northwestern side or the north side. I accept the attribution of the compass directional descriptions shown by Mr. Bramans annotations on this plan. A copy of this annotated plan is appended to this decision.

31. Attorney Richard Gallivan is an attorney long licensed to practice in Massachusets. Mr. Gallivan specializes in title examinations.

32. Mr. Gallivan testified that the phrase suitable for the grantees purposes, as used in the 1927 deed, was intended to refer to the method of travel set up in the easement, rather than the grantees future use of the locus. I found this line of evidence generally persuasive and adopt it.

33. Mr. Gallivan felt that, based upon ambiguous language in the deed, a plan would be necessary to establish the location of the right of way for those interested in the title to rely on a particular location.

34. Mr. Gallivan had no knowledge of any reasons why the right of way granted in 1927 would emanate from the northwestern side of the locus rather than the northeastern side of the locus. The evidence as I find it to be is consistent with this testimony.

35. Mr. Gallivan testified that he could not conclude that the Russett right of way was the right of way conveyed by the 1927 deed, but he could conclude that because the path of the Russett right of way appears on the 1944 Rowley Plan, the Russett right of way was by that time a traveled right of way.

36. Attorney Richard Golder also has been licensed to practice in Massachusetts for many years. He too specializes in real estate matters, including title examination.

37. Mr. Golder testified that the dotted lines on the 1944 Rowley Plan represent cart paths or rights of way that the surveyor saw when examining the parcel. I find this to be so.

38. Mr. Golder opined that the language of the 1927 deed clearly indicated that the right of way must emanate from the northeasterly side and was intended to provide access to Beach Road. I accept part of this testimony, finding that the 1927 deed shows the parties to it intended the easement to provide access to Beach Road.

39. Mr. Golder felt that, in the deed, the phrase from a point was ambiguous because it did not define that point. In his opinion, this ambiguity should be resolved by reading these words broadly to mean any point. I do not adopt this testimony.

40. Mr. Golder testified that he interpreted the deed to reflect an intent to convey an easement that would facilitate a broad range of purposes and uses of the locus. I do not adopt this testimony.

41. Mr. Golder noted that the Carlton to Herrick deed reserved a similar right of way for Carlton to use for access to Beach Road, but that the language in the Carlton-Herrick deed did not limit Carltons right of way to a point. This is so.

42. Mr. Golder testified that the Russett right of way is not the same right of way granted by the 1927 deed. Any subsequent relocation of the Russett right of way was therefore not, in Mr. Golders opinion, pursuant to the relocation terms included in the 1927 deed. I agree with these statements.

43. No witness, including the expert witnesses, had adequate information or knowledge to know, or to make inferences about, the terrain or topography of the locus in or around 1927.

44. No witness had knowledge of how either right of way depicted on the 1944 Rowley Plan was created.

45. No evidence was presented regarding which path or paths Godfrey may have used while he held title to the locus from 1927 to 1953.

46. There was no evidence presented to prove whether or not the establishment of Bayberry Road in this disputed stretch predates the Russett right of way.

IV. Discussion

An easement is a nonpossessory right to enter and use land in the possession of another. Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 663 (2007) (quoting Restatement (Third) of Prop. (Servitudes) § 1.2(1) (2000)). The benefit of an easement . . . generally authorizes limited uses of the burdened property for a particular purpose. Martin v. Simmons Props., LLC., 467 Mass. 1 , 9 (2014). If a deed intends to convey an easement, but the deed is not clear as to location, scope, or purpose, it is appropriate that a court assist in giving meaning to the instrument and the intention of the parties, as the court does in interpreting incomplete or insufficiently precise terms of a contract. Stone v. Perkins, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 265 , 268 (2003). In so doing, [t]he basic principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that their meaning is derived from the presumed intent of the grantor. . . ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998).

Following these interpretive guidelines, I conclude that the plaintiffs have carried their burden and have proven that a right of way benefiting locus exists at some location on what now is Bayberry Road. However, the terms of the 1927 deed--and the other proper evidence concerning its meaning--proves to me, as the trier of fact, that the intention of the parties to that deed was to establish the right of way so that it enters locus from what now is Bayberry Road where it abuts Lot 1005A, at and very near to the northwest corner of the locus (now Lot 1005A) and at a place which does not provide ingress and egress to Lot 1005B.

A. Where The Right Of Way Exists

The party asserting the benefit of an easement has the burden of proving its existence, its nature, and its extent. Martin, 467 Mass. at 10. However, the mere fact that the precise location is undefined does not negate the existence of the right of access. Cheever v. Graves, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 601 , 605 (1992). An easement is considered ambiguous when its meaning, as far as the right of way is concerned, is uncertain and susceptible of multiple interpretations. Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 26 (2006); see also Hogan v. Gordon, 82 Mass. App. Ct. 1122 (2012) (unpublished memorandum) (determining an easements terms are ambiguous when the deed's language does not clearly define the easement's location.). Although ambiguity does not negate existence, ambiguous terms allow room for the admission of parol evidence, to prove that the parties intended something different. Hamouda, 66 Mass. App. Ct. at 25 (quoting Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. 526 , 528 (1851)).

The 1927 deed grants ... a right of way suitable for the Grantees purposes from a point at the Northeasterly side of the lot hereby conveyed to said Beach Road. Using the metes and bounds description of the locus, which describes the boundaries of the locus by first locating the southeast corner, I have determined the corresponding northwest, northeast, southwest, and southeast corners and sides of locus, and conclude that the northeast side currently abuts Bayberry Road. I adopt as accurate the labels of the compass directions given for the sides and the corners of the locus as shown on Exhibit 35.

Although the side of the locus abutting Bayberry Road falls between the northwestern and northeastern corners, the evidence about the compass points on the various plans confirms that this side is at an approximately forty-five degree angle to what has been shown as magnetic north, so that this segment fairly can be said to be facing in a northeasterly direction. Each witness confirmed that the side of locus abutting Bayberry Road would be referred to as the northeastern side. Satisfied that the parties are justified in agreeing that Bayberry Road sits to the northeast of the locus, I conclude that the right of way must be at a point along the northeasterly side of the locus, or at a point along what now is Bayberry Road.

Acknowledging that Bayberry Road runs along locus to the northeastern side, the defendant contends that the original right of way created by the 1927 deed is not a pathway along the line of Bayberry Road, but rather is the Russett right of way. I find, however, that the Russett right of way never has entered the locus from its northeast side. The Russett right of way, both before and after the 1995 relocation effort, always has come into the locus on its northwestern side, after first passing over the Russett parcel. The Russett right of way, I find, historically cut across the Russett land after entering it somewhere in the vicinity of the junction of what is now Bayberry Road and Little Harbor Road, entering into the locus at a location on its boundary with the Russett parcel which is approximately fifty to seventy-five feet distant from the northwest corner of the locus. Based on the words used in the written agreement, the Russett right of way cannot be the original 1927 right of way, because it does not begin at a point on the northeastern side of the locus. See Sheftel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. at 179.

The defendant seems to urge that, notwithstanding that the words of the 1927 deed put the right of way at a point at the locus northeasterly side, there may have been a reason, topographical or physical, that led to the actual positioning of the right of way referenced in the deed on the northwestern side instead. But there is no proof of this which I find satisfying. If the defendant had presented evidence of some practical reason for the initial placement of the easement to the northwest side of the locus, instead of on the northeast side, there might be more merit in arguing that the Russett right of way is in fact the route of the originally granted easement. But no persuasive evidence was presented at trial to suggest any pressing necessity for placing or moving the easement to the northwestern side of locus at or around the time of the creative instrument. In fact, the witnesses were consistent in saying that the record included very little helpful information about the topography and ground conditions in and around the locus in 1927. I have no reason to believe there was any reason whatsoever the parties in and around 1927 would have had to cause the right of way to enter the locus from the northwestern side, as opposed to from the northeastern side (as explicitly granted). On the evidence which I have and find persuasive, I conclude that the location of the original right of way must exist at a point on Bayberry Road.

In the alternative, the defendant argues that the original 1927 right of way has been relocated as a result of subsequent use, pointing to the long-standing use of the Russett right of way. See Proulx v. DUrso, 60 Mass. App. Ct. 701 , 705 (2004) (easement relocated when the parties conduct showed that they had agreed a different easement route be substituted for the original). To prove such a relocation, there must be evidence of affirmative and willing participation in the relocation process, or acquiescence in the use of the different easement in lieu of the original. Id. Sufficient evidence of such acquiescence includes, but is not limited to, using that way as [the] exclusive access to and from [the] property. Id. For example, in the Proulx case, a landowner conveyed an easement to his neighbor to use the wood road as his right of way to reach the public road. For some undisclosed reason, the landowner fenced off the wood road, making it impassible, but constructed a gravel path as an alternate right of access to the public road. Instead of removing the fence to use the wood road, the neighbor used and improved the gravel path as his alternative route of ingress and egress. The court found the neighbors conduct constituted acquiescence to the relocation of the easement from the wood road to the gravel path.

In this instance, there is no evidence that the Russett right of way substituted for the original right of way, because there is nothing in the record that indicates to me, as the trier of fact, that Godfrey ever used the Russett path in lieu of the original right of way. In fact, the earliest recorded identification of the Russett path is in the 1944 Rowley Plan, which also shows a traveled way along Bayberry Road (although it was not identified on any recorded plan as Bayberry Road until 1946). It is reasonable to infer from the Rowley Plan that surveyor Walter Rowley observed two existing routes, either of which Godfrey may have used as his right of way to access the locus. Neither party was able to produce evidence to prove which path or paths Godfrey actually used. There was nothing in the nature of personal letters, personal sketches or maps, or earlier plans to nail down this important point. Of course, the 1927 Titus Plan referenced in the Godfrey deed would have been enormously helpful, but we do not have it. Walter Rowleys 1944 plan, though helpful to show in a rough sense the conditions a number of years after the 1927 deed, did not indicate which paths looked to be more intensively traveled or which path presented itself as a more usable or practical route than the other. Nothing on the 1944 Plan indicates whether either path appeared better maintained than the other, or whether substantial improvements had been made to one or both of the rights of way. More importantly, there was no evidence presented at trial that showed what was on the ground in 1927, nor from 1927 to 1944. In the Proulx case, the court was aware that the original easement, the wood road, was impassible because a fence prevented its use. In this case, however, there is no evidence suggesting barriers, physical conditions or topography prevented or preferred the use or maintenance of one path or the other. Without information about the specific topography of the locus at the relevant times, there is no reason to believe one path was more practical than the other, and nothing to support a conclusion that Godfrey acquiesced to any relocation of one route in favor of another. I cannot determine that one right of way was a substitute for the other, because the only reasonable inference I can draw from the record is that both paths existed, at least to some degree, as traveled paths as early as 1944.

Based on the language of the deed and the relevant testimony at trial, I determine that the plaintiffs have sustained their burden of showing that, as established in the 1927 deed, a right of way does exist, separately from the Russett right of way, at a point that must begin on the northeast side of locus, or at a point along Bayberry Road.

B . Where The 1927 Right Of Way is Located On Bayberry Road

Concluding that the plaintiffs have met their threshold burden of establishing that a right of way exists, located on the northeastern side of locus, the next task is to determine the point on Bayberry Road at which the 1927 deed positioned the right of way. When a deed does not specify a location for a right of way, the court looks to discern the intent of the parties to the instrument from the words used in the deed. Hamouda, 66 Mass. App. Ct. at 26; see also Adams v. Planning Bd. of Westwood, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 389 (2005). If the words themselves are not sufficiently illuminating, the court interprets the language of the grant in light of the circumstances attending its execution, the physical condition of the premises and the knowledge which the parties had. Perodeau v. O'Connor, 336 Mass. 472 , 474 (1957) (quoting Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. 102 , 103 (1940)). If that intent still lies in doubt, the court may resort to extrinsic evidence of the parties subsequent use and conduct if such use tends to explain or characterize the deed, or to show its practical construction by the parties, providing the acts relied upon are not so remote in time . . . . Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 632 (1990) (quoting Bacon v. Onset Bay Grove Ass'n, 241 Mass. 417 , 423 (1922)). Ultimately, a trial courts interpretation must give proper effect to both the language of the deed and the original purpose of the grant itself. Hogan, 82 Mass. App. Ct. 1122 . The burden of proof, however, remains with the plaintiffs. Foley v. McGonigle, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 746 , 746 (1975) (stating the proponent of the

easement has the burden of proving the nature and extent of any such easement.).

1. A Point Does Not Mean Every Point

Unlike the reference to the northeast side, the deeds reference to a point is at least a bit ambiguous, certainly to the extent that phrase does not fix any specific location and is susceptible to a variety of reasonable interpretations about where the easement was placed by the parties. See Hamouda, 66 Mass. App. Ct. at 26; Hogan, 82 Mass. App. Ct. 1122 . Based on this ambiguity, the plaintiffs argue that a point must be read to mean every point or any point on the northeastern side of the locus. This interpretation, however, attempts to capitalize on the ambiguity by giving the words a meaning they cannot bear. Although the point in question is not defined as to its location, and thus is ambiguous in that sense, there is no doubt that there is only one point, not multiple points, at which the right of way must emanate from the locus. Allowing the right of way to begin at every point is simply an unreasonable interpretation of the language included in the grant. Instead,at a point on the Northeasterly side is best reasonably interpreted to mean that Carlton intended to locate the right of way at one fixed point, albeit a point undefined in the words of the deed, and likely lost to us today due to the absence of the referenced 1927 Titus Plan.

I cannot bring myself to find that Carlton and Godfrey used the words they dida point to memorialize an intention to grant unfettered access into Godfreys new lot all along the line of its northeasterly boundary, or even at any point of Godfreys choosing along that boundary. If that had been the parties intention, they would have put the words rather differently. See Sheftel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. at 179 (stating that the particular language used is the most telling indication of the intended scope of the easement.).

I draw strength for this conclusion by looking just a short distance in time beyond the 1927 deeds execution. In 1928, Carlton conveyed all of his remaining land to Robert Herrick, except for a 5.8 acre parcel abutting the southeastern side of the locus and also abutting present- day Bayberry Road to the northeast. To avoid landlocking this piece, his last remaining parcel, Carlton reserved for himself a right-of-way suitable for Grantors purposes, from the Northeasterly boundary of the Grantors remaining land to the Beach Road, so-called.... This grant, written less than one year after the Carlton-Godfrey deed, is almost identical to the 1927 Godfrey easement--except that it does not reference a point on the northeastern boundary. The 1928 easement allows ingress and egress across the entire northeastern boundary, or across all of what has become Bayberry Road alongside Carltons 5.8 acre parcel, because the grant lacks any language that could be interpreted as limiting its scope. Simply put, there is a fundamental difference between a point, the word Carlton chose in his 1927 deed to Godfrey of our locus, and a line, which is what Carlton obviously was referring to when he made out the description in the 1928 deed. In light of this significant difference, the 1927 deeds inclusion of a point must reasonably be interpreted as a showing intention to limit the right of way to one particular location, rather than a broad grant to use every point along the northeast boundary as the right of way.

While it is not necessary for me to make such a finding to resolve the question tried to me, what I conclude occurred is that, in 1927, when Carlton sold the locus to Godfrey, there was already in existence a right of way leaving from the conveyed land along its northeastern side line, very close to its northwestern corner. This right of way headed from there in a northerly and westerly direction towards the Beach Road. It is fair to infer that this right of way, because it was in existence already, was known to the parties to the 1927 deed, and was depicted on the 1927 Titus Plan. It is for this reason that Carlton and Godfrey would have spoken of the right of way as proceeding from a point at the Northeasterly side of the lot.... The right of way existed, it had a known location, and it lay on the ground at a certain point.

After Carlton sold off the locus to Godfrey, he then parted with his remaining land, which Carlton sold to Herrick the following year, keeping only the 5.8 acre parcel abutting our locus on its southeasterly side. Until the sale to Herrick, Carlton had other land over which to pass to gain access to the 5.8 acre parcel and the rest of his holdings. When Carlton sold off the rest of what he owned to Herrick, he needed to preserve his right to locate and establish a new right of way, not using the land sold the year prior to Godfrey, to come in and out of the 5.8 acre parcel. He thus reserved a right that gave him a broad easement to bring his right of way into that parcel all along its northeastern boundary. The difference in the words used makes sense if this is what happened, and I conclude that it likely did.

I emphasize that, given the paucity of evidence about the true lay of the land in the 1920's, I cannot and do not find outright that this is what took place and physically existed in 1927 and 1928. I reach the findings and rulings that I do without needing to make hard and fast findings about what I infer well may have been the situation on the ground at the time of the 1927 and the 1928 deeds by Carlton. But the scenario I have described is certainly a likely one, and one which buttresses my conviction that the differences in the words used in the two grants were meaningful and intentionalthat those differences in the language used in the 1927 and the 1928 deeds resulted from choices made for good reason.

2. Suitable for the Grantees Purposes Is In Reference To Accessing Beach Road

The plaintiffs also focus on the phrase suitable for the grantees purposes, and argue that this should be interpreted to mean that the right of way extends along all of Bayberry Road, to accommodate various and varied uses of the locus. See Bedford v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 82 (2004) (concluding an easement unlimited in scope may be available for any reasonable use of the dominant estate). The plaintiffs argue that this interpretation is most consistent with the grantors intent because Carlton reasonably anticipated development and subdivision of the locus. In particular, the plaintiffs rely on the various deeds admitted into the record that show Carlton was in the process of subdividing his own property in 1927. See Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 260 (1964) (Where a description in a deed is of doubtful or ambiguous import, extrinsic evidence is admissible to show the construction given to the deed by the parties and their predecessors in title as manifested by their acts.). In light of this specific language, the plaintiffs argue that the most reasonable interpretation of the grantors intent is to locate the point on the Northeasterly side closest to the northeastern corner, because then the easement would allow subdivisions and development of the locus without landlocking any newly created subdivision lots.

I am not persuaded that this is the most reasonable interpretation of the deed. The plaintiffs argument is flawed because when ascertaining intent from the language used, the granted right of way must be read in its entirety . . . together with the then existing conditions. Patterson, 448 Mass. at 666; see also Hamouda, 66 Mass. App. Ct. at 27 (Deeds must be read as a whole, with reference to all of their terms.). By taking the phrase suitable for the grantees purposes out of context from the rest of the grant, the plaintiffs have again created ambiguity favorable to their cause. The plaintiffs would have the court read the grant as suitable for the grantees purposes in utilizing the locus. But the deed in fact reads, a right of way suitable for the Grantees purposes from a point at the Northeasterly side of the lot hereby conveyed to said Beach Road. The language included in the grant does not reference Godfreys purposes as to the use of the locus, but does reference accessing Beach Road, which we know, and all the witnesses confirmed, was crucial to Godfreys otherwise landlocked property. See Adams v. Planning Bd. of Westwood, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 389 (2005) (ambiguous language must be read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution.).

I interpret suitable for the grantees purposes to mean suitable for the grantee to access Beach Road. This is the dominant, and only really explicit, purpose of the right of wayto get out to the road. This interpretation is consistent with both the language of the grant, read in its entirety, as well as the attendant circumstance of getting Godfrey meaningful access to a public road. See Perodeau, 336 Mass. at 474. Nothing in the words used bespeaks any concern about subsequent development of the parcel being transferred. Locating the right of way at any point on Bayberry Road, or in the northeast corner of the locus, as the plaintiffs urge, is not only contradictory to the language of the deed, but also would be unreasonable and unnecessary for Godfreys purposegaining access to the public way. No good reason exists why Godfrey would need or desire to locate the access point connecting the right of way to his new land at a further distance from the stated destinationout, to the north and west, to Beach Road. I determine that the 1927 deed located the right of way on Bayberry Road at a definite point at or very near to the northwestern corner of the locus, where there would be the most convenient access to said Beach Road. Town of Bedford, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 81. This interpretation of the grant gives appropriate weight to both the language used in the deed, the attendant circumstances identified in the record, and the purpose of the grant itself.

I further conclude that, even to the extent Godfrey would have thought about someday divvying up his four acre parcel into smaller components (something I deeply doubt was on his mind in 1927) he would not have addressed this concern by bargaining with Carlton for a right to enter locus further to the southeast along what is now Bayberry Road. Even if he had been thinking about someday subdividing the land, Godfrey would not have sought to have his access point come into the locus at any greater distance than needed from the destination stated in the deed: Beach Road. If Godfrey had been concerned with making an additional lot out of what he was buying, he would have been able later to establish an adequate route from the point of access, at or near the northwestern corner of the locus, over the locus, to serve the newly subdivided lot or lots.

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that the division of locus took place in 1999, when Lot 1005A was conveyed out. That conveyance established two lots, each, unsurprisingly, with water frontage on Buzzards Bay. It is hard to imagine that Godfrey, if he ever even considered in 1927 that he might divide the locus, would have thought about doing it much differently than was done in 1999. The only real difference is that, if Godfrey had given the matter any reflection at all, he would have concluded that he would be able to reserve passage rights across the locus to reach a second lot; he would not have thought he needed, to serve future additional lots, access over what was then the remaining land of Carlton on the northeast. Indeed, when the plaintiffs sold Lot 1005A to its new owners in 1999, they too could have expressly of record kept rights to pass over that parcel to get to their retained land. They did not, and as a result they have had to assert the rights advanced in this litigation.

3. The Canon that Doubtful Language Ought Be Construed Against the Grantor Does Not Alter the Courts Findings and Rulings

The plaintiffs contend that even if, as I have concluded, there is evidence the 1927 deeds parties intended to locate the right of way near the northwestern corner of the locus, one canon of interpretation saves the day for the plaintiffsthe principle which requires that ambiguity within deeds be resolved in favor of the grantee. See Bernard v. Nantucket Boys Club, Inc., 391 Mass. 823 , 827 (1984) (citing Thayer v. Payne, 56 Mass. 327 , 331 (1848)) (It is a rule in the construction of deeds, that the language, being the language of the grantor, is to be construed most strongly against him."). I conclude that, even giving weight to this general interpretive precept, it does not change the ultimate findings and rulings I must issue in this case on the question tried.

First, I observe that this canon, where matters of description are concerned, is best and more often applied to resolve the tension between multiple distinctly conflicting provisions within a deed, and not so often to give meaning to one ambiguous descriptive provision. See Melvin v. Proprietors of the Locks & Canals on Merrimack River, 5 Met. 15 , 27 (1842) (construing the terms of the deed against the grantor when there are "two descriptions of the land conveyed, which do not coincide.). I note that in the case cited by the plaintiffs invoking this canon in their favor, Nantucket Boys Club, 391 Mass. 823 (1984), the court construed the language of the deed most strongly against the grantor only because there were two conflicting descriptions of the property within the same deed.

In any event, this principle is not an iron rule, which in all cases of ambiguity mandates that the court decide against a grantor. If that were so, grantors would never prevail in cases of this sort. The canon certainly can help break a tie where a real estate instruments words are difficult to parse, and there is no meaningful other admissible evidence to control and explain the doubtful meaning. In that case, it is not unfair to indulge the assumption that the grantor, who more controls the scrivening of the deed, should bear the blame if the words fail to speak clearly enough. But in this case, there are many other factors which counsel me to find and rule as I have. I have followed closely the provisions of the 1927 deed, and have found in them a distinct meaning that tracks the particular meaning of the words used. I have discerned a meaning that is fair and faithful to those words. That meaning is supported by the other proper evidence external to the deed, which supports the reading I have given the document. Here there is no occasion to apply the canon to upend the result called for by the clear weight of the evidence.

4. This is Not an Instance Where the Parties Never Located the Easement; The Location Of The Easement Is Not Equitably To Be Established by the Court

Finally, I am not persuaded by the plaintiffs argument that I should exercise equitable principles to locate judicially the right of way near the northeastern corner of the locus. In certain circumstances, the court is called upon to locate a right of way by striking a balance between minimizing the damage to the servient estate and maximizing the utility to the [dominant estate]. Restatement (Third) of Prop. (Servitudes) § 4.8, cmt. b (2000). Such an exercise acknowledges that the grantee is entitled to use the easement in a manner that is reasonably necessary for [the dominant estates] convenient enjoyment. Cater, 462 Mass. at 533 (quoting Restatement (Third) of Prop. (Servitudes) § 4.10 (2000)).

The role of the courts in this respect, however, ordinarily is limited to those situations where, from the outset, there is an absence of agreement by the parties. Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 533 (2012). In other words, when the parties create an easement, but leave its location unfixed, or to be located later within a broadly general area, the court may step in and, applying principles of equity, balance the rights of the burdened and benefited landowners to set, for the first time, the route of the easement.

For example, in Cater, the court felt it was appropriate to locate judicially the route and width of the easement, because the language of the deed and the evidence of subsequent use admitted in the record all indicated that the parties never established the location of the easement, and instead left its route and dimensions to be determined at a later date.

The case now before me is different. I am not required or able to locate the 1927 right of way using equitable factors, because the evidence does not indicate there was any absence of agreement between Carlton and Godfrey about where the right of way was. The 1927 grant is ambiguous is some respects, as explained above, but I am firmly satisfied that in that deed the parties agreed between themselves to a definite location of the right of way. In fact, there is ample evidence that grantor and grantee had settled on a specific point where the right of way would exit the locus and head out towards Beach Road. As I have said, the deeds explicit reference to the 1927 Titus Plan proves that the parties looked to that plan specifically to memorialize and illustrate their agreement about the right of ways definite location. Their failure to record or preserve that plan leaves us today somewhat unsure where exactly that location of the easement was planted by the parties, but I harbor no uncertainty that they did fix the right of way in a specific place. For this reason, I have not viewed my task in this case as deciding where, equitably, it would be best to locate the easement created in 1927, as a matter of original inquiry. Rather, my role is to determine, as well as I can from the available evidence, where the parties themselves put the easement on the ground in 1927. My conclusion is that they placed the easement along what is now Bayberry Road, but just at and very near to the northwest corner of the land conveyed in the 1927 deed. The right of way, as the parties placed it in 1927, would not in any case have extended to have any contact with the Pearsons Lot 1005Bs northeastern sideline, which begins seventy feet away from that northwest corner of Lot 1005A.

C. Conclusion

The Pearson family has held title to the locus since 1953. They were aware of the terms of their deeds, and familiar with the property. They knew that when they subdivided the locus in 1999, selling off Lot 1005A to third parties, the land they kept, Lot 1005B, could only be accessed over legally recognized rights of way. The Pearsons, as the sellers of lot 1005A, could have bargained for a record easement over the lot they sold for the benefit of the lot they kept. I do not hypothesize about why that did not happen. Faced with the reality that the record instruments contain no such right over Lot 1005A, the Pearsons are left, as a matter of record title at least, asserting that in 1927 their predecessor acquired a record right of way which reaches to where it connects with the parcel the Pearsons today still own. Their reliance on the terms of a ninety year-old deed to achieve this end is not borne out by the facts as I find them, and the controlling law I must apply.

I conclude that the 1927 right of way begins at one particular point on Bayberry Road, and that the point in question is located at and immediately near the northwest corner of the Lot 1005A. The right of way does not extend along Bayberry Road the full seventy-foot length of Lot 1005As boundary along Bayberry Road, and in no way reaches to any part of Lot 1005Bs 180.20 foot boundary along Bayberry Road. The Pearsons, as owners of Lot 1005B, have no record right under the 1927 deed to pass to and from their land onto and over Bayberry Road.

Because this trial was limited to determining, as a matter of the record title, as between the plaintiffs and this defendant, the location of the 1927 right of way, the parties have reserved the right to present evidence concerning claims for easements which may exist independent of record rights. The parties are to file, no later than twenty-one days after the date of this decision, a joint written report providing their views on the steps the court now ought take to bring this case to judgment.

RICHARD H. PEARSON and BONNIE B. PEARSON, Trustees of THE SOUTHWEST TRUST v. BAYVIEW ASSOCIATES, INC.

RICHARD H. PEARSON and BONNIE B. PEARSON, Trustees of THE SOUTHWEST TRUST v. BAYVIEW ASSOCIATES, INC.