Was it lawful for the Hopkinton Planning Board (Board) to allow a proposed Dunkin Donuts shop to be characterized as a retail store, instead of as a restaurant? Plaintiff Coco Bella LLC, (Coco Bella) an abutter to the proposed donut shop, thinks not, and for that reason appeals a decision of the defendant Hopkinton Board of Appeals (the ZBA) affirming the Planning Boards decision granting Site Plan Approval for property at 78 West Main Street (the Locus) belonging to defendant 2 High Street Realty LLC (2HS Realty). Defendant S.F. Management LLC (SFM) was the applicant before the Planning Board seeking to build a Dunkin Donuts on the Locus (the Project). Coco Bella argues that the proposed development at the Locus is not a permitted use under the Town of Hopkinton Zoning Bylaws (the Bylaw). SFM filed a Motion for Summary Judgment, alleging first, that Coco Bella lacks standing to

proceed on appeal and second, that the site plan approved by the Planning Board complies with the Bylaws zoning requirements and it is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. For the reasons stated below, summary judgment will enter for Coco Bella, and against the defendants, annulling the decision of the ZBA.

FACTS

The following material facts are found in the record for purposes of Mass. R. Civ. P. 56, and are undisputed for the purposes of the motion for summary judgment:

THE PARTIES AND THEIR PROPERTIES

1. Coco Bella is a Massachusetts limited liability company that owns property at 4 High Street, a/k/a 61 Elm Street, Hopkinton, by deed dated August 26, 2008, recorded with the Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds (Registry) at Book 51614, Page 109. Coco Bellas property is improved by a single-family dwelling. Edward J. Murphy (Murphy) is the manager and a member of Coco Bella. Coco Bella operates its property as a residential rental property. [Note 1]

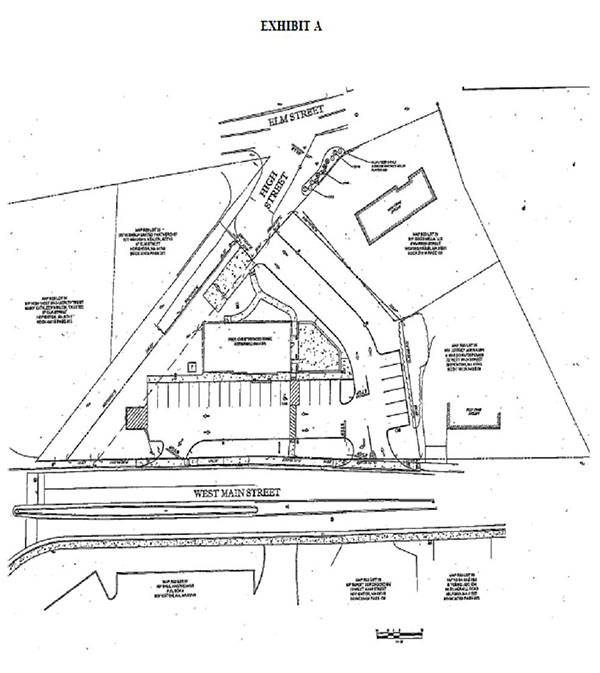

2. 2HS Realty owns the Locus by deed dated October 29, 2004, recorded with the Registry at Book 43999, Page 26. The Locus was originally a 29,543 square foot lot as described on a deed and shown on a plan of land dated March 12, 1955, entitled Plan of Land in Hopkinton, Mass., recorded with the Registry at Book 8436, Page 237. An additional 3,772 square foot strip was added to the Locus when the Town of Hopkinton (the Town) discontinued a portion of High Street, an abutting roadway to the rear of the Locus (the High Street Strip). [Note 2] The vote at town meeting to discontinue the High Street Strip, retaining only a utility easement, was taken on May 4, 2005, and notice was recorded in the Registry on August 25, 2011 at Book 57344, Page 432. [Note 3] The Locus is presently a 33,315 square foot lot, improved by a boarded-up single-family dwelling and a barn that have not been in use for some time. [Note 4]

3. The southerly lot line of Coco Bellas property abuts the Locus for 125 feet. [Note 5]

4. The Locus is located in a Rural Business (BR) zoning district, immediately adjacent to a Residence B (RB) zoning district, in which Coco Bellas property is located. In 1955, when a plan showing the Locus was recorded, the Locus conformed to the 15,000 square foot minimum lot area requirement for a BR district. The Bylaw was amended in 2009, increasing the minimum lot area allowed in a BR district to 45,000 square feet. [Note 6]

5. SFM, the applicant for the Dunkin Donuts shop proposed to be built on the Locus, is an operating entity that owns and operates several Dunkin Donuts franchise locations in Massachusetts. Virginio C. Sardinha, Jr. (Sardinha), is the manager of the franchises owned by SFM. [Note 7]

THE PROPOSED DUNKIN DONUTS

6. On March 28, 2013, SFM filed an Application for Site Plan Review with the Planning Board to demolish the existing dwelling and barn on the Locus, and to build a two-story 6,690 square foot building with office and retail space, including a Dunkin Donuts shop. [Note 8]

7. Public hearings on SFMs Application for the proposed Project were held on April 22, May 13, June 10, and June 24, 2013. To address concerns of the Planning Board and its consultants, the Site Plan was revised during the public hearings to reduce the size of the building to a 3,000 square foot one-story structure occupied solely by a Dunkin Donuts shop. There are three proposed entrances to the Project, two front entrances from West Main Street and a rear entrance from High Street, via Elm Street. The proposed Dunkin Donuts would provide both take-out and sit-in service. The building would contain 28 seats, tables and couches, seasonal outdoor seating, and would provide free-wifi. The site will also contain 24 parking spaces, landscaping, and a trash enclosure. There is no drive- through window proposed at this location. The menu will include coffee and other hot beverages, specialty beverages like smoothies and espresso-based beverages, egg, cheese, and meat sandwiches, as well as bagels, muffins, donuts, and other pastries. [Note 9]

8. By a decision dated and filed with the Town Clerk on July 10, 2013, the Planning Board approved SFMs Application and the Site Plan. After consulting with the building commissioner, the Planning Board classified the use of the proposed Project as a retail store, a use allowed as a matter of right in a BR district. [Note 10]

9. Pursuant to § 210-135.F, Coco Bella appealed the Planning Boards decision to the ZBA on July 30, 2013.

10. By a decision dated and filed with the Town Clerk on October 23, 2013, the ZBA denied Coco Bellas appeal to overturn the Planning Boards Site Plan Approval, finding that the Locus retained grandfather protection for its nonconforming lot area even after merger, and affirming the Planning Boards decision that the Project was a use permitted as a matter of right within the BR district. [Note 11]

THE BYLAW

11. Section 210-117.B of the Bylaw, amended in 2009, provides protection for certain lots that do not satisfy current minimum lot area and width requirements. The section provides:

Lot area and width requirements shall not apply to a lot which at the time of the adoption or amendment of this Chapter cannot be made to conform to the requirements for the district in which it is located, provided that said lot has been duly recorded by plan or deed or assessed as a separate parcel before the adoption or amendment of this Chapter.

12. Section 210-136 of the Bylaw governs the standards, decision criteria, and conditions needed for Site Plan Approval. Subsection 210-136.1.H requires the site plan to comply with all zoning requirements.

13. Section 210-23 of the Bylaw lists seven permitted uses in a BR district, two of which are relevant to the present action. Section 210-23 states in relevant part:

The following land uses and building uses shall be permitted in a BR District. Any uses not so permitted are excluded unless otherwise permitted by law or the terms hereof:

(A) Restaurants where all customers are seated and where no live commercial entertainment is offered.

(B) Retail stores, provided that not more than six employees are on the premises

14. The terms restaurant and retail store are not defined in the Bylaw, and the Bylaw does not include, either as a permitted use or as a use permitted by special permit, a restaurant where fewer than all customers are seated.

15. Under §§210-34 and 210-37.8 of the Bylaw, in industrial districts retail stores are allowed as a matter of right if they sell particular items including groceries, prepared take-out food, toilet articles, cosmetics, candy, sundries, medications, newspapers, magazines, and ice cream.

DISCUSSION

I. SUMMARY JUDGMENT STANDARD

Summary judgment is granted where there are no issues of genuine material fact, and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Ng Bros. Constr. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 643-44 (2002); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). The moving party bears the burden of affirmatively showing that there is no triable issue of fact. Ng Bros., supra, at 644. In determining whether genuine issues of fact exist, the court must draw all inferences from the underlying facts in the light most favorable to the party opposing the motion. See Attorney Gen. v. Bailey, 386 Mass. 367 , 371, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 970 (1982). Whether a fact is material or not is determined by the substantive law, and an adverse party may not manufacture disputes by conclusory factual assertions. See Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986); Ng Bros., 436 Mass. at 648. When appropriate, summary judgment may be entered against the moving party and may be limited to certain issues. Community Nat'l Bank v. Dawes, 369 Mass. 550 , 553 (1976); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c).

SFM has moved for summary judgment on two grounds: first, that Coco Bella lacks standing and second, that the Site Plan Approval did satisfy the zoning requirements and as such, judgment should be made in their favor as a matter of law. In response, Coco Bella argues that SFM has not rebutted its presumption of standing and alternatively, that it has offered sufficient evidence to support its standing. Coco Bella also asserts that the Site Plan Approval did not satisfy the local zoning requirements.

II. STANDING

As an abutter to the Locus, Coco Bella enjoys a rebuttable presumption that it is aggrieved and entitled to challenge the decision of the ZBA, pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17. Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Marotta v. Bd. of Appeals of Revere, 336 Mass. 199 , 204 (1957). SFM challenges Coco Bellas standing, contending that it is not an aggrieved party. If standing is challenged, the jurisdictional question is decided on all the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiffs from the presumption. Marashlian, supra, at 721, citing, Marotta, supra, at 204. The party challenging the plaintiff's presumption of standing as an abutter can do so by offering evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact. 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012), quoting Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 258 (2003). If a defendant offers enough evidence to warrant a finding contrary to the presumed fact, the presumption of aggrievement is rebutted, and the plaintiff must prove standing by putting forth credible evidence to substantiate the allegations. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, supra, at

701. Following rebuttal of the presumption by a defendant, plaintiffs have the burden of proving, by direct facts and not speculative evidence, that they would suffer a particularized injury as a consequence of a zoning boards decision. Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 120 (2011). The facts offered by the plaintiff must be more than merely speculative. Sweenie v. A.L. Prime Energy Consultants, 451 Mass. 539 , 543 (2008). On the other hand, if a defendant fails to offer sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption of standing, then the abutter is deemed to have standing, and the case proceeds on the merits. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, supra, at 701.

In a prior order denying SFMs Motion to Dismiss, the court (Grossman, J.) held that Coco Bella could rely on its presumption of standing as a preliminary matter, because the defendants had failed to rebut the presumption. The court must now decide, on summary judgment, whether Coco Bellas presumption of standing has been rebutted, and if so, whether it has offered sufficient credible evidence to support a finding that it is aggrieved.

SFM, by affidavit, describes the proposed Dunkin Donuts shop as providing both take- out and dine-in service, with 28 seats, tables, couches, seasonal outdoor seating, and 24 parking spaces. There would be three entrances onto the Locus, two front entrances from West Main Street and a rear entrance from High Street, via Elm Street, where Coco Bellas abutting property is located. [Note 12] The hours of operation are proposed to be from 4:00 A.M. to midnight, with employees closing the business around 12:30 A.M. No drive-through window is proposed.

SFM contends that Coco Bellas principal complaint about the proposed Dunkin Donuts is not one of actual harm in the use or enjoyment of its property, but rather it is Coco Bellas interest in the enforcement of the Bylaw so as to prevent a non-permitted use, a restaurant in which not all the patrons are seated, from being approved in the BR district. This is essentially characterized by SFM as a mere civic interest in enforcing a zoning bylaw, and not a cognizable injury that can confer standing. See Harvard Square Defense Fund, Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Cambridge, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 491 , 495-496 (1989). SFM submits that this is a general enforcement request and not a private injury, and how the ZBA and Board have chosen to interpret the Bylaw is insufficient to support a judicial appeal under G.L. c. 40A, §17. However, this argument by SFM is not enough to rebut the presumption of standing. In order to rebut a presumption of injury to Coco Bella in the use of its property, SFM does offer a Traffic Impact Study (unsupported by affidavit), purporting to demonstrate a lack of impact from traffic. The study analyzes data concerning traffic volume and patterns to project the amount of traffic during the week and on the weekends, and in particular during peak periods. It also determined the trip generation of the proposed development based on the type of use. Based on this information, the study concluded that the Project would result in only a one to four percent increase in the traffic on West Main Street, and therefore, little or no impact on Coco Bellas property. [Note 13] Overall, SFM offers little evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact to rebut Coco Bellas claims of aggrievement. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, supra, at 700. It primarily relies on the set of conditions imposed by the Planning Board in granting Site Plan Approval to suggest that Coco Bellas property will be protected and that therefore the alleged harms are without merit.

However, assuming the evidence presented by SFM is sufficient to rebut the presumption, it behooves Coco Bella only to come forward with credible evidence of a non-speculative injury. This it has done. The sole manager and member of Coco Bella, Edward Murphy, testified at his deposition that, based on what he understands about the plan for the Dunkin Donuts, cars and trucks will stop in front of the house and park, traffic will be a cut through (based on his belief that High Street was narrowed because it had become a cut through), noise level from the patio, car radios at all hours, smell from baking, idling cars, idling delivery trucks, smell from the trash, delivery at all hours is not restricted. Nonstop car or truck exits from the fast food establishment, compressor noise and exhaust at all hours, dumpster pickup in front of my property, trash in the yard. [Note 14]

These concerns are reasonable, plausible and not speculative, based on the undisputed facts in the record concerning the proposed facility, its proposed hours of operation, and its proximity to Coco Bellas property at 61 Elm Street, abutting the proposed Dunkin Donuts. One does not need to be an expert to credibly testify that these types of impacts are likely to occur when a proposed Dunkin Donuts shop is located next door to a single-family residence, where there is a parking lot entrance adjacent to the residential property, where there will be 24 parking spaces in the parking lot next to the residential property, where there will be a trash Dumpster in the vicinity of the residence, where the Dunkin Donuts will be open from approximately 4:00 A.M. to midnight, with its outdoor lights on from 4:00 A.M. to 12:30 A.M., where there will be seasonal outdoor seating with no limits on hours of use, and where there undisputedly will be traffic at all open hours and truck deliveries perhaps even during earlier or later hours. See 81 Spooner Road, LLC, supra, at 704-705 (no need for expert testimony as to impact on density); Marashlian, supra, at 722-723 (no need for expert testimony as to impact of loss of street parking spaces); Epstein v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 752 , 759-760 (2010) (expert testimony unnecessary to demonstrate loss of light and air from building to be constructed five feet from plaintiffs building).

Coco Bella has demonstrated its aggrievement with credible evidence on issues the Planning Board acknowledged during the public hearing process and addressed to a limited degree, with conditions requiring, for instance, that box trucks deliver only from West Main Street, but at unlimited hours. [Note 15] Though the applicant proposed virtually unrestricted hours of operation, there was no limit placed on the hours for the shop in the Site Plan Approval, and it is acknowledged that exterior lights would remain on outside the building as late as 12:30 A.M., and some even after the close of business. [Note 16] The attempt in the Planning Boards decision to address some (but by no means all) of the injuries claimed by Coco Bella does not overcome, and in some ways validates, the evidence presented by Coco Bella that these claimed injuries are real and not speculative.

The court must draw all reasonable inferences in favor of Coco Bella, as the nonmoving party. I find that Coco Bella has presented credible evidence of a specific, non-speculative injury sufficient to withstand summary judgment and to establish its standing.

III. ZONING REQUIREMENTS FOR SITE PLAN APPROVAL

Where a use allowed as a matter of right is proposed, a planning board does not have the discretionary authority to deny site plan approval, but may only impose reasonable conditions that do not have the effect of denying the proposed use. Prudential Ins. Co. of America v. Board of Appeals of Westwood, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 278 , 281-282 (1986). Coco Bella properly does not argue that the Planning Board (or the ZBA) failed to impose adequate restrictions, but rather argues that the Planning Board and the ZBA had no authority to approve the site plan because the proposed use is not allowed as a matter of right. The Bylaw specifically incorporates this limited authority of the Planning Board to deny approval, by requiring that the site plan must comply with all zoning requirements. Bylaw, §210-136.1.H. There are two bases on which Coco Bella makes the argument that the site plan failed to comply with all zoning requirements. First, it asserts that the proposed Project does not conform to any permitted uses in a BR district under §210-23. Second, Coco Bella contends that the Locus is not a buildable lot because it does not satisfy the minimum lot area requirement of a BR district under the Bylaw, and that the exemption in §210-117.B for undersized lots does not apply in this circumstance. I address each argument in turn below.

A. Use: Restaurant or Retail Store?

Section 210-23 of the Bylaw lists several uses permitted as a matter of right in a BR district, including restaurants where all customers are seated and retail stores, provided that not more than six employees are on the premises. [Note 17] Coco Bella argues that the proposed Dunkin Donuts should be classified as a restaurant under the Bylaw, albeit one that is prohibited because it is not a restaurant where all customers are seated. SFM contends that the Project was properly characterized as a retail store. Because the Bylaw does not define either of these two terms, the parties dispute over the meaning of this language, and the intent of the Bylaw, lies at the center of this case. Accordingly, the courts task is to decide if the Bylaw prohibits restaurants where not all patrons are seated, as Coco Bella asserts, or whether, as SFM claims, establishments, such as the proposed Project, are permitted as-of-right as retail stores.

Throughout the Bylaw, only two use classifications specifically address uses pertaining to food. First, restaurants are allowed in several districts, including the BR district, where the use is described as Restaurants where all customers are seated. [Note 18] SFM concedes that not all patrons of the shop will be seated and thus, the Project cannot be permitted as a restaurant under the Bylaw. Second, in industrial zoning districts, retail stores are permitted that sell specific items such as groceries, prepared take-out food, toilet articles, cosmetics, [and] candy. [Note 19] Since the Dunkin Donuts is not proposed to sell any of the enumerated items and its food is made to order, not pre-prepared, it does not fit into this category either (and is not, in any event, in an Industrial district). SFM submits that because there is no other classification in the Bylaw that would squarely fit such a use, the Town is permitted to, and intended to, interpret retail store broadly under §210-23 so as to encompass the proposed Dunkin Donuts shop. SFM states there is precedent for this interpretation based on the permitted use of similar shops selling take-out food in the BR district. [Note 20] SFM submitted, as evidence of the Towns consistent interpretation of retail store as encompassing this type of use, copies of building permits for a Starbucks, another Dunkin Donuts, and a Café Mocha Express in the BR district, that were evidently issued without the need for any variance or other zoning relief.

Coco Bella insists that the proposed Dunkin Donuts is a restaurant, based on the food preparation and cooking occurring in the shop and the fact that Dunkin Donuts own website refers to its locations as restaurants. [Note 21] To support its position, Coco Bella points to testimony given by Virginio Sardinha, a manager of the franchises owned by SFM. Sardinha testified in his deposition that the Dunkin Donuts menu would include hot beverages, specialty beverages like smoothies and espresso-based beverages, sandwiches, bagels, muffins and donuts. [Note 22] Sardinha also testified that food preparation would occur at the shop involving portioning ingredients such as meats, cheeses, and eggs that arrive in bulk. The sandwiches are not pre-packed, but are made upon the placement of an order by a customer. Muffins and bagels arrive frozen, but are baked in ovens on site. Donuts arrive partially cooked, with frosting or filling added at the Locus. Additionally, local food permits are required for the operation, including a milk and cream license, a common victualler license, and a food establishment license. [Note 23] Sales at the proposed Dunkin Donuts will be subject to the Massachusetts state meals tax, which is imposed on sales of meals by a restaurant. 840 CMR 64H, §6. Based on this evidence, Coco Bella contends that the Project must be classified as a restaurant. In creating separate line items for restaurants and retail stores in a number of different zoning districts, Coco Bella postulates that the Bylaw acknowledges a distinct difference between the two uses. Coco Bella asserts that if the Bylaw was intended to allow food establishments where not all customers are seated, such a provision would have been explicitly listed in the Bylaw.

The court is ultimately left with the task of providing the legal interpretation of local legislation. The interpretation of bylaws is a question of law for the court, not a question of fact, to be determined by ordinary principles of statutory construction. Framingham Clinic Inc. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Framingham, 382 Mass. 283 , 290 (1981); Bldg. Comm'r of Franklin v. Dispatch Communications of New England, 48 Mass. App. Ct. 709 , 713 (2000). The court interprets municipal bylaws and ordinances according to ordinary principles of statutory construction. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Pship v. Bd. of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 477 (2012). The court first looks to the statutory language as the principal source of insight into legislative intent. Id. When the meaning of the language is plain and unambiguous, the court enforces the statute according to its plain wording unless a literal construction would yield an absurd or unworkable result. Commonwealth v. DeBella, 442 Mass, 683, 687 (2004) (stating that the court will not resort to extrinsic aids in interpreting the statute when the ordinary meaning of words yield a workable and logical result).

Where ambiguities exist in the language of the bylaw, however, the court owes some deference to a local boards reasonable construction of its own bylaw. Petrillo v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Cohasset, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 453 , 456 (2006); Shirley Wayside Ltd. Pship, supra, at 475. Ambiguities exist when multiple interpretations lie within the band of a reasonable reading, as to the meanings of terms included in, and the intentions lying behind, the ordinance's words. Livoli v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Southborough, 42 Mass. App. Ct. 921 , 923 (1997). Deference is owed to a local zoning boards interpretation, because the local board is deemed to have special knowledge about the history and purpose of its zoning bylaw. Deadrick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 85 Mass. App. Ct. 539 , 545 (2014). Such deference, however, is given only when that interpretation is reasonable. Pelullo v. Croft, 86 Mass. App. Ct. 908 , 909 (2014). An incorrect interpretation of a bylaw is not entitled to deference. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Pship, supra, at 475 (a judge should overturn a local boards decision when the boards conclusion is not supported by any rational view, or when the reasons given by the board lacked substantial basis in fact and were in reality mere pretexts for arbitrary action or veils for reasons not related to the purposes of the zoning law).

Absent express definition, the meaning of a word or phrase used in a local zoning enactment is a question of law and is to be determined by ordinary principles of statutory construction. Shirley Wayside Ltd. PShip, supra, at 477. The terms used in a zoning bylaw are to be read in the context of the bylaw as a whole and to the extent consistent with common sense and practicality, they should be given their ordinary meaning. Kurz v. Bd. of Appeals of North Reading, 341 Mass. 110 , 112-113 (1960); Hall v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Edgartown, 28 Mass. App. Ct. 249 , 254 (1990). The words usual and accepted meanings are derived from sources presumably known to the bylaws enactors, such as their use in other legal contexts and dictionary definitions. See Commonwealth v. Zone Brook, Inc., 372 Mass. 366 , 369 (1977). A zoning board of appeals is entitled to all rational presumptions in favor of its interpretation of its own by-law, provided there is a rational relation between its decision and the purpose of the regulations it is charged with enforcing. See Livoli, supra, at 923; Bldg. Commr of Franklin, supra, 715-718; Advanced Dev. Concepts, Inc. v. Town of Blackstone, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 228 , 231 (1992); Cameron v. DiVirgilio, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 24 , 28-29 (2002).

In order to determine the validity of the Boards and the ZBAs determination that the proposed Dunkin Donuts may properly be classified as a retail store, and not as a restaurant seating less than all of its customers, the courts first task is to examine the context of the use of these terms in the Bylaw. The Bylaw is of the prohibitive variety, in which uses not explicitly listed as permitted as a matter of right, or by special permit, are deemed to be prohibited. The preamble to the list of permitted uses in each district makes this clear, providing in relevant part that, [a]ny uses not so permitted are excluded. In the BR district, in which the Locus lies, the first two uses listed are: Restaurants where all customers are seated and where no live commercial entertainment is offered, and Retail stores, provided that not more than six employees are on the premises. With minor differences, this is consistent with the treatment of these uses in other districts. In all of the districts in which any kind of restaurant is allowed, (Business, Downtown Business, Rural Business, Industrial A, and Industrial B) the use is limited to those establishments where all customers are seated. The only differences are in the Industrial A district, in which a prohibition against live entertainment is not present, and in the Industrial B district, where there is a limitation of 100 seats, and the closing time must be no later than 11:00 P.M. Retail stores are permitted in all of these districts, with different limitations in different districts, including the limits on the number of employees and on size.

The restriction to restaurants in which all customers are seated suggests that the use described is what is colloquially known as a sit-down restaurant. There is no corresponding use item listed in the Bylaw for restaurants where fewer than all customers are seated, or for what is colloquially known as a fast-food restaurant. Other municipalities have struggled with differing treatments of fast-food restaurants and sit-down restaurants, with various definitions of the two types of restaurants, and with distinctions as to how to draw the line between the two where the difference is not always clear. For example, the Boston Zoning Code distinguishes between sit-down and fast-food restaurants by differentiating between establishments where food is sold for on-premises consumption and those that sell on-premises prepared food or drink for off-premises consumption or for on-premises consumption if, as so sold, such food or drink is ready for take-out. But even with this relatively straightforward distinction, the Boston Zoning Code makes an exception to the fast-food definition by carving out an allowance for incidental sale of over the counter foods by retail establishments including grocery stores and bakeries. [Note 24]

The limitation of the permitted use restaurant in several districts, to those restaurants in which all customers are seated, leads to the inescapable conclusion that the drafters of the Bylaw understood that there are other restaurants in which fewer than all of the customers are seated. That the drafters of the Bylaw chose not to list as an allowed use or as a special permit use, these other restaurants in which fewer than all customers are seated, indicates not that they meant to include such establishments within the ambit of the term retail stores, but rather, that they chose to leave such uses, by their exclusion, subject to the provision that uses not so permitted are excluded. This conclusion is consistent with common sense and practicality, and with the ordinary meaning of the terms restaurant and retail store. Kurz, supra, at 112-113.

The term retail store is a general term of broad application, and were it not for the presence of the term restaurant in the Bylaw, there would be some appeal to SFMs argument that the term retail store as used in the Bylaw was intended to encompass restaurant uses where not all the customers are seated. Blacks Law Dictionary defines retail as [t]he sale of goods or commodities to ultimate consumers, as opposed to the sale for further distribution or processing. Blacks Law Dictionary (10th ed. 2014). Similarly, the American Heritage Dictionary defines retail as [t]he sale of goods or commodities in small quantities to the consumer. Am. Heritage Dictionary 1186 (4th ed. 2002). Both of these sources suggest that the term retail is to be given a broad definition. There is no limitation placed on the kinds of goods or commodities that can be sold, nor does the definition distinguish food and beverages from other types of retail items that can be sold.

Courts have also sometimes chosen to provide a generously broad definition to the term retail store when interpreting a bylaw or statute. In Commonwealth v. Moriarty, the court determined a tavern was a retail store within a statute requiring that retail stores be closed between 7 a.m. and 1 p.m. on Columbus Day, after finding that serving alcohol was considered a sale of beverages. 311 Mass. 116 , 120 (1942). In Petros v. Superintendent & Inspector of Bldgs of City of Lynn, the court found that a small poultry store, in which live fowl was slaughtered to be sold to retail meat markets and directly to customers, was permitted as a retail store under the City of Lynns ordinance. 306 Mass. 368 , 371 (1940). The court in Petros acknowledged that a primary component of what makes something a retail use is when goods and commodities are sold in small quantities, such as are adapted to individual purchasers. Id.; see also Commonwealth v. Greenwood, 205 Mass. 124 , 126-127 (1910) (distinguishing wholesale sales from those made in small quantities, which are to be regarded as sales at retail); Commonwealth v. Poulin, 187 Mass. 568 , 568 (1905) (To retail is to sell in small quantities.); Lowe's Home Centers, Inc. v. Town of Auburn Planning Bd., 2008 WL 5115069, at *6 (Mass. Land Ct. Dec. 5, 2008) (a proposed home improvement store was considered a retail store rather than a lumber yard because the sale of lumber and building materials was coupled with other merchandise sold at the store directly to consumers); Town of Wellesley v. Javamine, 22 Mass. L. Rptr. 12, *1-2 (2006) (finding that a proposed Dunkin Donuts offering exclusively take-out food, with no tables, chairs or counters for in-store consumption, not required to obtain common victuallers license).

However, courts have not permitted uses to be considered retail stores when there is another more specific and appropriate use classification in the bylaw. See Magnone v. Planning Bd. of Sutton, 76 Mass. App. Ct. 1115 , 1115 (2010) (finding that a station selling gasoline at retail was not a retail store, but rather constituted the provision of automobile services, a prohibited use in the zoning district). Where there is a more specific term in the Bylaw that more accurately describes the use than the general and broad term retail store, the more specific term will govern. See, Silva v. Rent-A-Car Center, Inc., 454 Mass. 667 , 671 (2009) ([G]eneral statutory language must yield to that which is more specific). In the present case, the Bylaw employs the much more specific term restaurant to describe a use permitted as a matter of right in the BR district.

Restaurant is also defined in G. L. c. 64H, §6(h) as any eating establishment where food, food products, or beverages are provided and for which a charge is made, including but not limited to, a café, lunch counter, private or social club, cocktail lounge, hotel dining room, catering business, tavern, diner, snack bar, dining room, vending machine, and any other place or establishment where food or beverages are provided

This definition not only better describes the proposed Dunkin Donuts at the Locus, but it is directly applicable to the Locus and serves as the basis upon which sales at the Locus would be subject to the state meals tax. The Massachusetts sales tax is imposed on sales of meals by a restaurant. 840 C.M.R. 64H.6.5(1)(A). The proposed Dunkin Donuts will also be required to obtain a common victuallers license to operate the proposed facility. The words common victualer, in Massachusetts, by long usage, have come to mean the keeper, of a restaurant or public eating-house. Liggett Drug Co. v. Bd. of License of the Commrs of the City of North Adams, 296 Mass. 41 , 49 (1936).

Given this context, it is apparent, and I so find, that the use of the word restaurant in the Bylaw, even with reference to restaurants in which all customers are seated, precludes the characterization of the proposed Dunkin Donuts shop as a retail store and requires that it be characterized as a restaurant at which fewer than all customers are seated. Because this use is not listed as a use either permitted by right or by special permit in the Bylaw, it is prohibited.

B. Dimensional Requirements

Given my conclusion with respect to the propriety of the proposed use of the Locus, it is unnecessary for me to reach the issue whether the construction as proposed would violate the dimensional requirements of the Bylaw. However, I do so in the event that the use issues upon which this decision is based are resolved by variance, change in the Bylaw, or otherwise. In both its appeal to the ZBA and its complaint to this court, Coco Bella asserts that when the Locus merged with the High Street Strip, the change in lot area eliminated any grandfather protection. Coco Bella contends that since the Locus is nonconforming, the change in status from the existing residence and barn to the proposed Project requires the issuance of a special permit for a change in a nonconforming use with respect to lot area. Conversely, SFM argues that the Locus does still retain grandfather protection and that §210-117.B of the Bylaw exempts the Locus from satisfying the current minimum lot area requirement.

A general principle [of zoning law is] that adjacent lots in common ownership will normally be treated as a single lot for zoning purposes so as to minimize nonconformities with the dimensional requirements of the zoning by-law ordinance. Seltzer v. Bd. of Appeals of Orleans, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 521 , 522 (citations omitted), rev. denied, 400 Mass. 1107 (1987); see also Asack v. Bd. of Appeals of Westwood, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 733 , 736 (1999) (A basic purpose of the zoning law is to foster the creation of conforming lots.), quoting Murphy v. Kotlik, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 410 , 414, n. 7 (1993). This common law doctrine of presumed merger of adjacent lots applies even if the lots held under common ownership were acquired at different times. Vetter v. Zoning Bd. of App. of Attleboro, 330 Mass. 628 , 630-631 (1953). When this occurs, adjacent lots in common ownership are normally treated as a single lot for zoning purposes so as to minimize nonconformities with dimensional requirements. Under this doctrine, a property owner can avail himself of an exemption for a nonconformity if adjacent land owned by the property owner, that minimizes the nonconformity, is included. Asack, supra, at 736. The rationale behind the doctrine is that such a landowner has the power to comply with zoning requirements by adding such land to the substandard lot, thus precluding him from reaping the benefits of the exemption unless he uses such adjacent land to minimize the nonconformity. LEsperance v. Cohen, 15 LCR 665 , 669 (2007) citing Sorenti v. Bd. of Appeals of Wellesley, 345 Mass. 348 , 353 (1963). The crucial inquiry for grandfathering purposes is the status of the lot immediately prior to the zoning change that rendered the lot nonconforming. Adamowicz v. Ipswich, 395 Mass. 757 , 762763 (1985); see Boulter Bros. Constr. Co., Inc. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Norfolk, 45 Mass. App. Ct. 283 , 286287(1998).

There is no dispute that the plan for the Locus was recorded showing it as a separately owned lot from the High Street Strip in 1955. The Locus was a 29,543 square feet parcel that complied with the 15,000 square feet minimum lot area requirement. The square footage of the Locus was increased by the discontinuance of the adjacent High Street Strip as a public way in 2005. In 2009, the Bylaw was amended to increase the minimum lot area in a BR district from 15,000 square feet to 45,000 square feet. After the change in the Bylaw, the Locus was grandfathered as a pre-existing lawful nonconforming lot under §210-117.B. Coco Bella argues that this merger caused the Locus to lose the protection of the exemption in §210-117.B. This is an incorrect application of the merger doctrine.

The Locus has existed as a matter of record since 1955, and therefore, predated the zoning change that rendered it dimensionally nonconforming. When it merged with the High Street Strip, this did not cause the Locus to lose its protected status. Such protection is lost only when a lot owner has adjoining land available to satisfy a dimensional requirement, but chooses not to add such land to the substandard lot. Nonconforming exemptions remain available to property owners where adjacent substandard lots are merged yet the nonconformity still remains, which occurred in the present situation. The Locus cannot be made to conform to the minimum lot size through the addition of adjacent land that is now in common ownership. The addition only worked to reduce the existing nonconformity by adding approximately 3,700 extra square feet of land to the Locus. Moreover, the usual application of the merger doctrine involves property owners who purchase adjacent lots. That is not the case here, where a portion of an adjacent roadway was abandoned by the Town through no action of the owners of the Locus. Nothing in the record indicates that 2HS Realty purchased or was ever separately deeded the High Street Strip.

Coco Bellas argument fails for the additional reason that the High Street Strip was not actually added to the Locus upon the discontinuance of a portion of High Street in 2005. Rather, the additional real estate was already part of the Locus, but it was not available for use because it was subject to the publics rights to High Street as a public way. Upon discontinuance, it became available for use by the abutting owner, who, pursuant to the Derelict Fee Statute, G. L. c. 183, §58, already owned it to the centerline.

Following Coco Bellas interpretation and eliminating grandfather protection in such circumstances would be inconsistent with the policy of requiring that available adjacent real estate be merged and available for use to reduce the nonconformity of nonconforming lots. Since 2HS Realty and SFM have reduced the nonconformity of the Locus by including the High Street Strip, they may avail themselves of the statutory exemption for prior lawful nonconforming lots. Accordingly, I find that §210-117.B of the Bylaw protects the Locus from the Towns current minimum lot size requirements. Because the Locus is a lawfully nonconforming lot, not considered undersized for purposes of the Bylaw, it may be built upon without the need for additional dimensional zoning relief. If the use issues upon which this decision is based are resolved by variance, change in the Bylaw or otherwise, the Locus will retain the protection afforded it with respect to lot area by §210-117.B of the Bylaw. Until such change, however, it is appropriate to grant summary judgment in favor of Coco Bella and against the defendants on the merits.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, the SFMs Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED, and summary judgment will enter in favor of Coco Bella, annulling the decision of the ZBA.

So Ordered.

COCO BELLA LLC v. TOWN OF HOPKINTON BOARD OF APPEALS, and its Members, Roy Warren, G. Michael Peirce, Tina Rose, Michael DiMascio, June Clark, Kelly Knight, and John Savignano, 2 HIGH STREET REALTY LLC and S.F. MANAGEMENT LLC.

COCO BELLA LLC v. TOWN OF HOPKINTON BOARD OF APPEALS, and its Members, Roy Warren, G. Michael Peirce, Tina Rose, Michael DiMascio, June Clark, Kelly Knight, and John Savignano, 2 HIGH STREET REALTY LLC and S.F. MANAGEMENT LLC.