At issue is whether the fence separating the abutting properties in Stoneham owned by Linda A. Salera and Lauri Weinstein is on Ms. Saleras or Ms. Weinsteins property and whether either of them have established title by adverse possession to the fence or the land between the fence and their common boundary. After trial, I find that the fence lies entirely on Ms. Saleras property and that Ms. Weinstein and her husband David Amentola have not established title by adverse possession to the land between their boundary and the fence.

Procedural Background

Linda A. Salera (Salera) filed her three-count Verified Complaint and Motion for Lis Pendens on December 24, 2013, naming Lauri Weinstein Amentola (Weinstein) and David Amentola (Amentola) as defendants (together, the Amentolas). The three counts are of the Verified Complaint are (1) Petition to Require Action to Try Title; (2) Action to Recover Freehold Estate; and (3) Adverse Possession. On January 15, 2014, a hearing on Saleras Motion for Lis Pendens was held, and the Motion was allowed.

The Amentolas filed their Verified Answer and Counterclaims, and Motion for Lis Pendens on May 7, 2014. On May 19, 2014, a hearing on the Defendants Motion for Lis Pendens was held, and the Motion was denied without prejudice.

A pre-trial conference was held on November 13, 2014. A view was taken on January 21, 2015, and a two-day trial was held on January 21-22, 2015. The court heard testimony from Stephen J. Russo, Linda Salera, Richard Vecchio, Richard Goulette, Lauri Weinstein, Bethany Cassin Gaita, David M. Amentola, Elliot Kerner, Diane Salley, and Judy Petri. Exhibits 1-25 were marked. Defendants Motion for a Finding in its Favor at the Close of Evidence was denied. Saleras Post-Trial Brief was filed on March 18, 2015, along with Requested Findings of Fact and Ruling of Law. Defendants Post-Trial Brief was also filed on March 18, 2015, along with Proposed Findings of Fact and Proposed Findings of Law. Plaintiffs Motion to Strike Argument II of Defendants Post-Trial Brief (Motion to Strike) was filed on March 23, 2015, and the Amentolas filed their reply on March 27, 2015. Closing arguments were heard on March 24, 2015. The matter was taken under advisement. This Decision follows.

Findings of Fact

Based on the view, the exhibits, the testimony at trial, and my assessment of credibility, I make the following findings of fact:

Facts Relating to Ownership of the Properties

1. Salera is the record owner of 3 Dale Court, Stoneham, Massachusetts (the Salera Property) by a deed from her father, John L. Salera, reserving unto himself a life estate, dated June 11, 2003 and recorded with the Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds (registry) at Book 40154, Page 96. Exh. 4D.

2. The Salera Property has been in the Salera family since 1946 when it was purchased by Saleras grandfather, Frank Salera, who had already owned the property at 1 Dale Court since 1929. The Salera Property was conveyed to Saleras parents, John and Concetta Salera, by a deed dated January 31, 1972 and recorded in the registry at Book 12158, Page 176. Exhs. 4B-4C, 5C; Tr. 1:72.

3. Salera grew up and lived in the house from the time of her birth in 1952 until 1971, when she moved out of the state. She did not return to Stoneham, Massachusetts until 2000. Salera resumed residing at the Salera Property in August of 2005. In 2012, Saleras father passed away. Tr. 1:72-74, 100, 145.

4. Weinstein is the record owner of 5 Dale Court, Stoneham, Massachusetts (the Weinstein Property), by a deed dated December 15, 1998 and recorded with the registry at Book 29524, Page 590. Co-defendant Amentola is married to Weinstein and also resides at 5 Dale Court, but is not a record owner of the Weinstein Property. Exhs. 3K, 5B. Tr. 1:170, 263, 290.

5. The relevant predecessors in Weinsteins chain-of-title begin in 1970, when Ella Kelleher conveyed the Weinstein Property to Hollis and Judith Petri (the Petris) by a deed dated April 17, 1970 and recorded with the registry at Book 11822, Page 562. Petri conveyed the Weinstein Property to Richard and Ernestine Pashoian (the Pashoians) by a deed dated September 12, 1972 and recorded with the registry at Book 12286, Page 37. Following a series of mesne conveyances from 1972 to 1985, Kevin and Diane Salley (Salley) acquired the property by a deed dated May 31, 1985 and recorded with the registry at Book 16196, Page 119. Salley conveyed the Weinstein Property to Patricia A. Hoffman (Hoffman) and Elliot J. Kerner (Kerner) by a deed on June 24, 1986 and recorded with the registry at Book 7130, Page 375. A little over a year later, Hoffman and Kerner conveyed the Weinstein Property to Bethany Cassin (Cassin) and Michael A. Gaita (Gaita) by a deed dated August 3, 1987, recorded with the registry at Book 18431, Page 488, who owned the property for about eleven years until conveying it to Weinstein in 1998. Exhs. 3C-3K; Tr. 2:38-39, 43, 94, 109, 119.

Facts Relating to the Boundary Line

6. At trial, the location of the boundary line between the Salera and Weinstein Properties (Subject Properties) was disputed. Title to the Subject Properties derives from a June 11, 1859 conveyance by a deed from Clarissa Stone to Mary A. Eastman (Eastman) for the properties now known as 1, 3, 5, and 7 Dale Court, recorded with the registry at Book 818, Page 234. The Weinstein Property was first conveyed out by a deed from Eastman to Matilda M. Dale (Dale), dated May 31, 1873, and recorded with the registry at Book 1271, Page 203 (1873 Deed). The 1873 Deed provides a complete metes and bounds description of the Weinstein Property. [Note 1] Exhs. 2, 3A.

7. Over a decade later, 1 Dale Court and the Salera Property (3 Dale Court) were conveyed together from Lyman Dike (Dike), the Administrator of the estate of Eastman, to Dale, by a deed dated August 18, 1884 (1884 Deed) and recorded with the registry at Book 1689, Page 62. The 1884 Deed provided only a bounds description, stating that the conveyed parcel was bounded northerly by land of said Matilda M. Dale (i.e. the Weinstein Property). Exh. 4A.

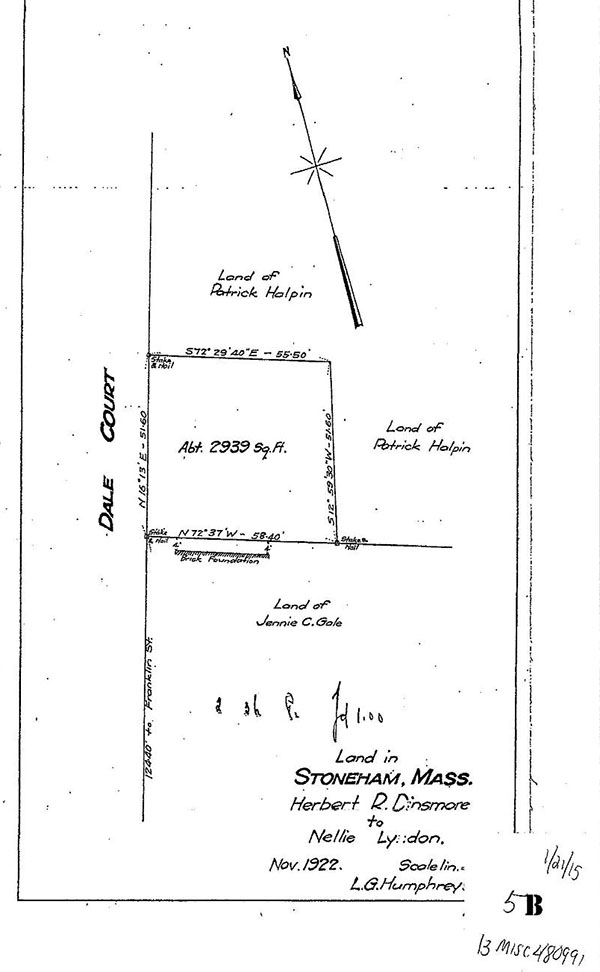

8. In 1922, the Weinstein Property was surveyed, and a plan entitled Land in Stoneham, Mass., Herbert R. Densmore (Densmore) to Nellie Lydon (Lydon), November 1922, L.B. Humphrey, C.E. (1922 Plan), attached here as Exhibit A, was prepared and recorded with the registry in Book 4576 in connection with Densmores conveyance of the Weinstein Property to Lydon by a deed dated December 1, 1922 (1922 Deed) and recorded with the registry at Book 4575, Page 590. The description of the Weinstein Property in the 1922 Deed contains the same metes and bounds as the 1873 Deed as well as a point of beginning:

Beginning at a stake at the southwesterly corner of the granted premises on the easterly line of said Dale Court and at land formerly of Mary A. Eastman [i.e. 3 Dale Court], later of Jennie C. Gale, said point of beginning being one hundred twenty-four and 4/10 (124.4) feet northerly along the easterly line of said Dale Court from the northerly line of Franklin Street. . . .

The point of beginning states that the distance from the northerly line of the intersection of Franklin Street (the nearest perpendicular street) and Dale Court to the northwesterly corner of the now Salera Property is 124.4 feet. Subsequent deeds in Weinsteins chain- of-title recite the same metes and bounds description found in the 1922 Deed, and reference the location of the southwesterly corner of the now Weinstein Property as 124.4 feet from the northerly line of Franklin Street, incorporating the 1922 Plan by reference. Exhs. 3B-3K, 5B.

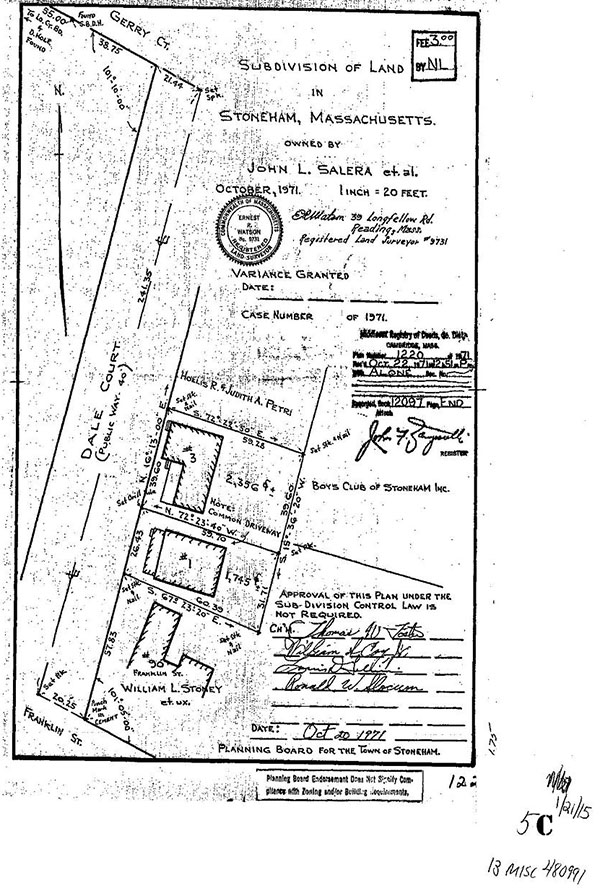

9. Saleras grandfather, Frank Salera, acquired 1 Dale Court from Herbert Richardson by a deed dated April 3, 1929 and recorded with the registry at Book 53, Page 450. Years later, the Salera Property (3 Dale Court) was also conveyed to Frank Salera from Florence Pike by a deed dated April 9, 1946 (1946 Deed) and recorded with the registry at Book 6960, Page 25. As in the 1884 Deed from Dike to Dale, the 1946 Deed provided only a bounds description, stating once again that the Salera Property was bound Northerly by land formerly of Matilda M. Dale (i.e. the Weinstein Property). In 1971, 1 Dale Court and the Salera Property were subdivided and a subdivision plan was created entitled Subdivision of Land in Stoneham, Massachusetts, Owned by John L. Salera et. al., dated October 1971 and recorded with the registry in Book 12097 (the 1971 Plan), attached here as Exhibit B. The 1971 Plan shows the distance from the northerly line of Franklin Street to the northwesterly corner of the Salera Property as 123.86 feet (determined by adding together the three frontage dimensions listed on the 1971 Plan57.83, 26.43, and 39.60). All subsequent deeds conveying the Salera Property reference the 1971 Plan. Exhs. 4A-4D, 5C; Tr. 1:72.

10. Stephen J. Russo, P.L.S. (Russo), a licensed Massachusetts professional surveyor since 1990, with 44 years of survey experience and currently a survey manager with Millennium Engineering, Inc., visited the property in 2010 to do a retracement survey of the Salera Property at the request of Salera (2010 Resurvey). Exh. 8; Tr. 1-32-36.

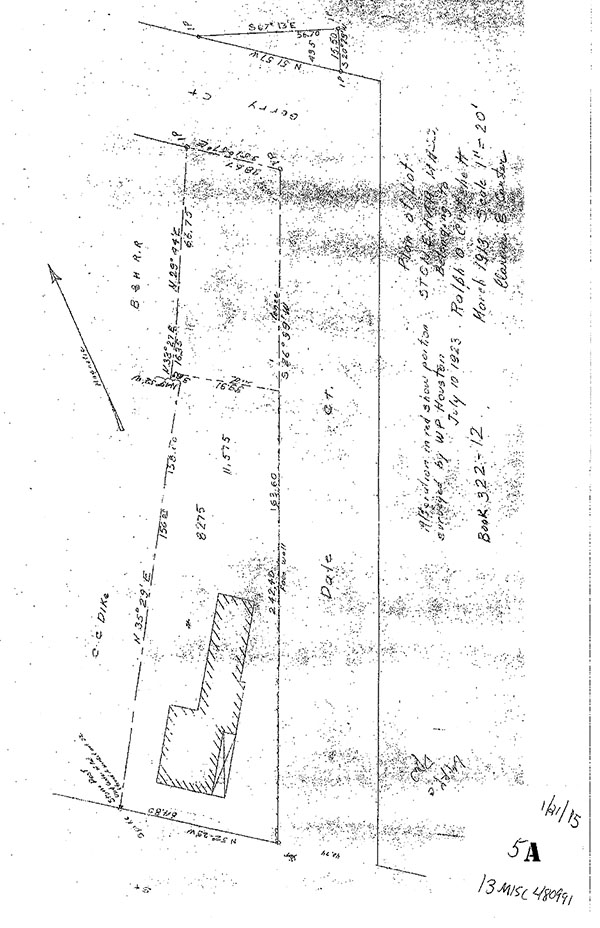

11. In order to complete his 2010 Resurvey, Russo relied on the 1971 Plan. Retracing the 1971 Plan proved difficult after Russo was unable to identify any markers or monuments used in creating the 1971 Plan. Additional plans for the Salera Property found in the registry also showed markers or monuments that Russo could not locate. Since Russo could not find identifiable markers at or around the Salera Property, Russo decided to establish the point of beginning from Franklin Street. In order to do this he used markers found on a plan from 1913 (1913 Plan) provided by the Town of Stoneham (the Town), attached here as Exhibit C, showing a retaining wall along Dale Court and a stone post located on Franklin Street. Exhs. 5A, 5C, 8.

Russo testified that after locating the retaining wall, he pushed the survey down easterly along the northerly line of Franklin Street in an attempt to create where the location is. And this is based on occupation and improvements by both the Town and the private owners, because we could not find any markers and monuments going down the street. We didnt have any monuments that the town said would assist in that. So we used the occupation. And we pushed that down maybe 250 feet or so. We also went in the other direction, past the stone monument, to get the occupation of the concrete sidewalk, so that we have concrete sidewalk on both sides, to establish the northerly line of Franklin Street. To establish the easterly side line of Dale Court, Russo also used the location of the retaining wall on the opposite side of the street and offset that by 40 feet. Tr. 1:47-49.

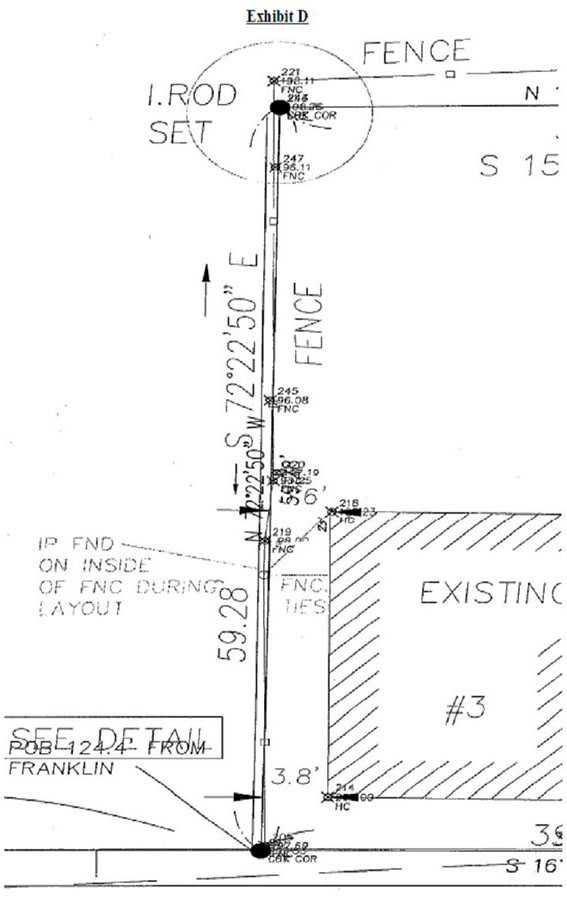

Once the side line of Dale Court was established, Russo calculated the location of the northwesterly corner of the Salera Property by adding up frontage distances shown on the 1971 Plan from northerly line of Franklin Street. This distance came to 123.86 feet. [Note 2] From the northwesterly corner, Russo was able to extend the boundary line towards the rear of the property to recreate the 1971 Plan. Based on Russos 2010 Resurvey relying on the 1971 Plan, he identified two areas where the existing fence extends beyond the boundary of the 1971 Plan, a total of nine square feet in area (a four square foot encroachment by the upper portion and a five square foot encroachment by the lower portion of the fence). Exhs. 5C, 8, 9; Tr. 1:40-41, 44, 46-47, 54.

12. Russo next ascertained the point of beginning from Franklin Street to the southwesterly corner of the Weinstein Property. Relying on the 1922 Plan and collecting data in the field, Russo developed an AutoCAD worksheet. Data points were stored in the measuring unit itself and taken back to his office where he downloaded the information into his computer to create the AutoCAD drawing. After comparing the data points collected from surveying the Subject Properties, based on the 1922 and 1971 Plans, respectively, Russo identified an inconsistency in the point of beginning distances from Franklin Street to the northwesterly corner of the Salera Property (a.k.a. the southwesterly corner of the Weinstein Property). While the 1971 Plan had a distance of 123.86 feet to the corner of the lots, the survey developed from the 1922 Plan showed a distance of 124.4 feet. This resulted in a gap between the two boundary lines of 6.48 inches. This discrepancy is shown on an AutoCAD worksheet, attached here as Exhibit D. Exhs. 5B, 5C, 9; Tr. 1:61-64.

13. According to Russo, no portion of the fence extends beyond the boundary of the Weinstein Property as shown on the 1922 Plan and the AutoCAD worksheet. I credit Russos testimony as to the location of differing boundary lines found in comparing the 1922 Plan and 1971 Plan. Exhs. 5B, 5C, 9; Tr. 1:63.

14. Based on the documentary evidence in the record and Russos testimony, I find that the boundary line, as described in the 1922 Plan and Deed is the record boundary line between the Subject Properties. The Weinstein Property was the first to be conveyed out of common ownership. The 1873 Deed describes metes and bounds that correspond to the 1922 Plan and Deed. The 1922 Deed additionally contains the point of beginning distance of 124.4 feet from Franklin Street to the southwesterly corner of the Weinstein Property. This property description remains consistent throughout subsequent conveyances in Weinsteins chain-of-title. When the Salera Property was conveyed out in the 1884 Deed and again in 1946, only a bounds description was included with the deeds. Based on the record provided, the first instance that metes or the point of beginning distance from Franklin Street are included in the deed description is not until 1972, referencing the 1971 Plan. Moreover, Weinstein did not have the property surveyed and presented no rebuttal expert testimony to challenge or oppose Russos conclusions. Thus, I find that the northerly boundary of the Salera Property extends all the way to the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property, as per the metes and bounds descriptions found in Weinsteins chain-of-title and the 1922 Plan. Exhs. 3A-3K, 4A-4C, 5B.

Facts Relating to the Fence

15. The fence at issue is located along the northerly boundary of the Salera Property and the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property. Based on my finding that the boundary line between the Subject Properties is in accordance with the 1922 Plan, the entire fence is located on the Salera Property.

16. The fence is comprised of two parts. The upper portion of the fence is located along the northerly boundary line between and at the front the two properties. The lower portion of the fence begins after a downward slope in the land, and continues along the disputed boundary line toward the rear of both properties. Exh. 24; Tr. 1:199; View.

17. The backyard of the Subject Properties extends to and abuts a different fence belonging to the Boys Club of Stoneham (Boys Club), which runs along the rear of both properties, perpendicular to the lower portion of the fence. Exh. 15-4; Tr. 1:74-75; View.

18. At one time, the upper and lower portion were both wooden stockade fences. The lower portion of the stockade fence was oriented with the finished side facing the Weinstein Property and the unfinished side facing the Salera Property. The upper portion, which has remained a wooden stockade fence, has the opposite orientation. When both portions were wooden stockade fences, they were not connected. A handrail running across the gap between the fences was installed at some point for ease of access when using stairs that led to the upper portion of Saleras side yard. Exhs. 7 pp. 13, 34-35, 15-115-8, 15-16; Tr. 1:77, 79, 197-199; 2:75-76; View.

a. The Lower Portion of the Fence

19. Saleras father erected a white picket fence along the northerly boundary line of the Salera Property at least prior to 1970. Judy Petri, a predecessor of Weinstein from 1970 to 1972, remembers the picket fence existing in the lower portion when she moved in, and testified that she believed the bottom section of the fence belonged to the Saleras. Tr. 1:86, 2:125-127.

20. In the summer of 1980, Saleras father replaced the picket fence with a wooden stockade fence. In the process, he affixed metal pipes along the entire length of the back of the fence for support. Exh. 10; Tr. 1:84-86, 89, 93.

21. Weinsteins predecessors from 1985 onwardSalley, Kerner, and Gaita testified that the stockade fence was already in existence when they acquired the property, although they were not aware of who had installed it. In addition, they testified that they did not maintain or repair the wooden fence during their residency. Weinstein also did not inquire as to who owned the fence when she purchased the property in 1998. Exh. 10; Tr. 2:46, 50-53, 106- 107,116, 125-127, 203.

22. In 2005, when Salera began residing at the Salera Property, she wanted to replace the lower portion, now 25 years old, with a white vinyl fence. Prior to replacing the lower portion, Salera gave notice to the Amentolas of her intentions; they raised no objection. After purchasing the white vinyl fence from Home Depot, Salera hired Gerald Riopelle (Riopelle) to remove the existing stockade fence and replace it with the vinyl one. Exhs. 11-13.

In his deposition, Riopelle testified that he took down the existing stockade fence and installed the vinyl fence in the same location. He stated that when replacing the fence, he made sure that the poles of the new fence fit within the holes created by the existing fence. Riopelle recalled that when installing the new fence he removed a six inch tree and cut out roots from some other trees on the Weinstein Property [b]ecause it was right were the fence would have gone. Riopelle also testified to removing a stump with roots from the Weinstein Property and pushing loam from Weinsteins garden away from the fence so that he could remove the stockade fence and install the vinyl fence. Riopelle asserted that he ran into some trouble when he reached the rear of the Salera Property where the new fence would intersect with the Boys Club fence. The vinyl fence panels only came in six foot sections, too large for the remaining gap to reach the Boys Club fence. Riopelle stated that to remedy this, he cut one of the panels to fill in the gap. He testified that he then took a PVC pipe, drilled two holes at the top, filled it with cement and clamped it to a pipe on the Boys Club fence. The purpose of the PVC pipe, Riopelle contends, was to support the cut panel as the fence intersects and turns the corner in front of the Boys Club fence. Riopelle testified that he finished the installation of the lower portion around October 2005. After he was finished, Riopelle stated that he connected the lower portion to the upper portion of the fence. Exh. 7 pp. 10-15, 18-29, 34-37; Exhs. 14, 24; View.

23. The Amentolas never objected to replacing the lower portion of the fence. They believe that the new vinyl fence was not built in the same location as the preexisting stockade fence and it now encroaches into their property. Before 2005, when the wooden stockade fence still existed, there was a PVC pipe was inside the Amentolas yard, up against the Boys Club fence. After the vinyl fence went up, the PVC pipe was not visible. The Amentolas contend that the PVC pipe now at the end of the vinyl fence is the same PVC pipe in their yard, indicating that the new fence was installed closer to and possibly encroaching on the Weinstein Property. They also point to the removal of the trees, stump, and roots during the installation as evidence that the location of the fence has shifted farther toward the Weinstein Property. The Amentolas did not hire their own surveyor to confirm its location in relation to their boundary line. Exhs.

21-24; Tr. 1:172, 183, 190, 191, 214, 216, 230-235, 2:11, 23-24, 67, 85; View.

24. I find that the lower portion of the fence was constructed by Saleras father. The question of whether the vinyl fence was actually put in a different location, closer to the Weinstein Property, is highly disputed and the evidence is contradictory. Either Riopelle put the new fence in the same location as the old fence and moved the PVC pipe to its current location, or he installed the new fence farther to the north than the original fence, so that it met the PVC pipe in its original location. It is not necessary to decide this factual issued. Even crediting the Amentolas testimony and assuming the fence was moved, it does not encroach on the Weinstein Property. As I previously found, the boundary line between the Subject Properties is in accordance with the 1922 Plan, and thus, the entire fence remains located on the Salera Property.

b. The Upper Portion of the Fence

25. There was conflicting evidence as to the ownership of the upper portion of the fence. Salera testified that she remembered her father erecting the upper portion of the stockade fence, along with a perpendicular portion that served as a privacy panel to the sidewalk. Her father also affixed metal pipes along the back of the upper portion for support, as he did when he built the lower portion of the fence later. When Salera had the lower portion replaced in 2005, she also requested Riopelle to replace the perpendicular wood privacy panel with a new panel. Exhs. 15-7, 15-8; Tr. 1:89-90, 99-100; View.

26. Maria Staggs (Staggs), the maternal aunt of Salera and sister of Concetta Salera, wife to Saleras father, generally concurred. Staggs first visited the property in 1947 and continued to visit with relative frequency until she moved away in July 1969. Staggs testified that both the upper and lower fence were there at least as early as 1969 and built by Saleras father. She recalled a particular occasion before leaving in 1969, sitting on the front porch of the Salera Property with her sister. She described the front portion of the fence as sticking out right to the sidewalk, with a perpendicular portion that went along the sidewalk from the front of the fence to the Salera house, enclosing the side of the Salera Property. Staggs stated that the perpendicular portion of the stockade fence was there for safety reasons because there was a slope that would go down the side of the house and at the end of the house there was a three or four foot drop of land. Staggs did not remember a similar perpendicular fence along the sidewalk in front of the Weinstein Property. Staggs testified as follows:

Q: You were asked about the fence that exists today being the same as the fence that was erected some time prior to July 20 of 1969. Can you describe, generally, what that fence looked like that you witnessed in 1969?

A: Well, it was a regular stockade fence that started from the back of the house to the front of the house right to the sidewalk. And it looked rather strange to me that it suck out like a sore thumb.

Q: Was it a fairly new fence in 1969?

A: Well, yes.

Exh. 6 pp. 9, 12-17, 19-20.

27. Conversely, Petri, a predecessor of Weinstein, testified that she installed the upper portion of the fence shortly after moving to the Weinstein Property in 1970, primarily for safety reasons because she had three young children at the time. Petri stated that it wasnt a very safe place to live because there were so many kids walking by. Petri testified as follows:

Q: Can you describe your home and property to us?

A: Okay. The property as it was when I bought it?

Q: What it was, yes.

A: There was no fence attached to the upper section at all. And I had little children, so we put in a stockade fence that went from the house, the sidewalk to the back. So it was a 3-sided fence

Q: And there was no fence along the front of your property, along the sidewalk on Dale Court?

A: Oh, absolutely a fence. I had to block off that whole section for children.

Q: Prior to you acquiring the property, though, there was no fence there?

A: There was never any fence there.

After 44 years since she had resided in the house, Petri could not remember many details about the fence, including the fence company that installed the stockade fence. She did recall with particularity a gate along the sidewalk that allowed entry to the side yard of the Weinstein Property and that she felt safe allowing her children to play in the yard because it was completely fenced off. Petri did not recollect whether the Weinstein Property was surveyed prior to putting in the fence. None of the other predecessors to Weinstein had knowledge of who owned or had installed the upper portion of the fence. Tr. 2:46-47, 105-106, 114, 120, 122, 125, 127.

28. The Amentolas also asserted that the fence must have been built by their predecessors based on the orientation of upper portion, with the nicer finished side facing the Salera Property and the unfinished side facing the Weinstein Property, since it is common knowledge that the nicer side is supposed face outward. Salera testified that the fence was oriented in that manner because her father wanted the nicer side of the fence to face them since he was paying for it. Salera testified that her father would have positioned the entire fence with the finished side facing their property, but he decided to flip the lower portion at the time because he was worried about the neighbors children climbing up it. Tr. 1:77; 94-95, 197-198, 203.

29. I find that the upper portion of the stockade fence was constructed by the Saleras prior to July 1969. I credit Petris testimony insofar as to find that she installed the portion of the fence in front of the Weinstein Property that runs along the sidewalk to the Amentolas house. As she repeated numerous times, Petris primary concern was the safety of her children and blocking off access to the street. Staggs testified that, unlike the Salera Property, there was no perpendicular fence along the sidewalk in front of the Weinstein Property in 1969. Petri lived at the Weinstein Property over 44 years ago and has since moved about ten times. I find that Petri is mistaken about the extent of her construction of the fence, and she only installed the section along the sidewalk in front of the Weinstein Property, and not along the boundary line. Exh. 6; Tr. 2:122-123.

Discussion

Salera brought an action to try title and to recover freehold estate, seeking a determination that the fence is located entirely within her property, or, alternatively, that she has acquired ownership of both the upper and lower portions of the fence through adverse possession. The Amentolas assert an adverse possession claim for the upper and lower portions of the fence and property, and alternatively argue that this is a partition fence and Salera may not unilaterally alter the fence from its present location without the agreement of the Amentolas.

A. Record Title

Prior to discussing my legal conclusions below, I repeat my factual finding that the northerly boundary of the Salera Property and the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property is that shown in the 1922 Plan and described in the metes and bounds descriptions found in Weinsteins chain-of-title, so that the fence lies entirely within the Salera Property. The location of a disputed boundary line is a question of fact to be determined on all the evidence, including the various surveys and plans, and the actual occupation and use[s] by the parties. Ellis v. Ashwood Realty, LLC, 19 LCR 520 , 523 (2011) quoting Hurlbut Rogers Mac. Co. v. Boston & Maine R.R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). Deed construction is part of that analysis.

Deeds of abutting properties may describe a common boundary line differently (e.g. giving it a different length, or referencing different monuments), creating ambiguity. But that ambiguity does not preclude the courts ability to determine the location of that line, placing it wherever the totality of the evidence indicates. Indeed, differing descriptions of the same physical line are so frequently encountered that surveyors have terms to describe the gaps such differences createhiatus, defined as an opening; a gap; a space [;] [a] gap between two deeds. McCarthy v. McDermott, 18 LCR 405 , 406 (2010) quoting C.M. Brown, et al., Brown's Boundary Control and Legal Principles at 387-388 (4th ed., 1995) ("Brown's Boundary Control"). The general principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that they are to be construed so as to give effect to the intent of the parties. Town of Stoughton v. Schredni, 7 LCR 61 , 66 (1999). Rules of deed construction provide a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004). When abutter calls are used in deed descriptions, the land of the adjoining property owner is considered to be a monument. [Note 3] Id. Monuments, when verifiable, are thus the most significant evidence to be considered. Ouellette v. McInerney, 19 LCR 41 , 42 (2011).

When presented with expert surveying and title testimony, a court must assess the opinions offered. The court must decide which . . . expert it finds more credible, basing such assessment on the experts analysis, taking into account the other evidence presented, including the documentary evidence, particularly the deeds and plans that lend support and corroboration to each opinion. Lombard v. Cook, 20 LCR 325 , 326 (2012). "No surveyor or court has authority to alter or modify a boundary line once it is created. It can only be interpreted from the evidence of where that boundary is located." Brown's Boundary Control § 2.6 at 32. If the location of the survey lines are uncertain from lack of control of known fixed monuments, and various surveyors might place the lines in different places, subsequent occupational conduct, such as fences and improvements, are sometimes helpful evidence of the original lines and may be indicative of the originally intended grant. Fulgenitti v. Cariddi, 292 Mass. 321 , 325 (1935) ("Acts of adjoining owners showing the practical construction placed by them upon conveyances affecting their properties are often of great weight."); Bacon v. Onset Bay Grove Ass'n, 241 Mass. 417 , 423 (1922); Abbott v. Walker, 204 Mass. 71 , 73 (1910); see also Brown's Boundary Control § 11.22 at 273. The law, however, does not require absolute certainty of proof to determine a boundary line, but merely a preponderance of the evidence. See McCarthy, 18 LCR at 406, citing M. Brodin and M. Avery, Handbook of Massachusetts Evidence (8th Ed.), § 3.3.2(a) at 67.

To begin with, I find the expert opinion of Saleras surveyor, Russo, persuasive and supported by the weight of the evidence. While none of the stakes or other monuments called for in the deeds of the Subject Properties survived, making his task difficult, Russos methodology and determination of the location of the two boundary lines using the 1922 Plan and 1971 Plan was sound. Though he did not proffer an opinion as to which line was the correct one, Russo did acknowledge the discrepancy between the lines and noted that according to the 1922 Plan, the entirety of the fence is located on the Salera Property. Accordingly, crediting the 1922 Plan would give Salera record title to the fence and the underlying land.

The Weinstein Property, which was first conveyed out of common ownership by the 1873 Deed, has had a consistent deed description from that time to this through all intervening conveyances. In the 1873 Deed, the Weinstein Property is described as starting at a stake on Dale Court extending southeasterly 58.4, thence 51.6 north from that point to another stake, thence 55.5 west from that point to a third stake, and finally 51.6south from that point to close at the first stake mentioned. The point of beginning from Franklin Street to the starting stake (124.4) appears in the 1922 Plan and Deed and is mentioned, along with the metes and bounds, in every subsequent deed in Weinsteins chain-of-title. Exhs. 3A-3K, 5B.

Conversely, Saleras chain-of-title has provided varying property descriptions or descriptions that lack the detail needed to ascertain the boundary lines. When the Salera Property was conveyed out in the 1884 Deed and again in the 1946 Deed, only a bounds description was included with the deeds, stating the property was bound Northerly by land formerly of Matilda M. Dale (i.e. the Weinstein Property). Not until 1972 were metes or the point of beginning from Franklin Street (123.86) included in the deed description. Exhs. 4A-4C.

Bounds descriptions generally eliminate gaps and overlaps since abutting descriptions calling for one another ensure one common line between them. Courts have generally ruled that abutters, if identifiable, are classed as monuments and must be honored. Browns Boundary Control §3.24 at 68. Since the Salera Property was conveyed out of common ownership a decade after the Weinstein Property, and only contained a bounds description referencing the Weinstein Property as its northerly bound, I find that the northerly boundary of the Salera Property extends to the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property, in accordance with the 1922 Plan, eliminating the 6.48 inch gap between the two boundary lines.

Furthermore, Weinstein did not have her property surveyed and did not provide any experts of their own to counter Russos conclusions. They simply argue that Salera has offered no explanation as to why the Court should rely on the 1922 plot plan. The Amentolas have failed to offer an explanation as to why I should not rely on that plan or should rely on the 1971 Plan, see Defendants Post-Trial Brief at 13. The totality of the record evidence, based on the deeds and plans, and Russos testimony, persuades me that the 1922 Plan is accurate. Therefore, I fix the boundary between the Subject Properties as the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property as described by metes and bounds in their chain-of-title and shown on the 1922 Plan referenced therein in. This means that the entire fence is situated on the Salera Property, and that Salera is the record owner of the entirety of the fence and the land upon which it sits.

B. The Amentolas Adverse Possession Claims

Since I find that the entire fence is located on the Salera Property, the Amentolas adverse possession claim is limited to the portion of the property between the fence and the boundary line (i.e. the Strip), per the 1922 Plan. Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years. Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). All these elements are essential to be proved, and the failure to establish any one of them is fatal to the validity of the claim. In weighing and applying the evidence in support of such a title, the acts of the wrongdoer are to be construed strictly, and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof of an actual occupancy, clear, definite, positive, and notorious. Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 209-210 (1853). If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968) (internal citations omitted). The test for adverse possession is the degree and nature of control exercised over a disputed area, the character of the land, and the purposes for which the land is adapted. Ryan, 348 Mass. at 262. The burden of proof in any adverse possession case rests on the claimant and extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession. Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 847 (2004). The Amentolas adverse possession claim therefore turns on what activities were conducted in the Strip over the 20 years prior to the filing of this action in December 2013.

Because the fence was built by Salera or her father and lies entirely within the Salera Property, in order to prevail on their adverse possession claim, the Amentolas must establish 20 continuous years of open, notorious, adverse, and exclusive use of the Strip itself, not merely use of the back yard to which Weinstein has title. As discussed further below, I find that the Amentolas have not proffered sufficient evidence showing adverse possession of the Strip.

The Amentolas have only lived at the Weinstein Property since 1998 and must rely on tacking to fulfill the 20 year statutory requirement. Tacking is the theory whereby adverse possessors in privity of estate with the claimant may be tacked on to fulfill the required twenty year period. Leonard v. Leonard, 89 Mass. 277 , 277 (1863). The Amentolas seek to tack by arguing that testimony from their predecessors-in-interest is sufficient to establish open, notorious, adverse, and exclusive use over the twenty year period. At trial, the Amentolas provided direct testimony from Weinsteins predecessors about such use.

Salley, Weinsteins predecessor from 1985 to 1986, testified that she rarely used the backyard of her property. Tr. 2:110. Salley did state that she raked, mowed, and cleaned up the yard, which required her to go up near the fences in that area of the Strip. Tr. 2:110. Kerner, the next predecessor-in-interest from 1986 to 1987, testified that his wedding ceremony was on the upper section of the yard and his wedding reception, with approximately 100 people, was in the lower section of the yard. Tr. 2:95-96. Like Salley, Kerner also stated that he mowed and raked the lawn within the Strip all the way up to the fences. Tr. 2:96.

Cassin, who owned the property for eleven years following Kerner, testified that her family did not frequently use the lower portion of the yard. Tr. 2:49-50. Cassin stated that she did not garden or have anything planted along the fence in the lower area of the Strip. Tr. 2:50. She averred that her children and dogs may have played in that vicinity, but they really didnt hang out down there and it wasnt a heavily trafficked area. Tr. 2:50. She did not know whether her children and dogs, when they played in that area, went up to the fence. Tr. 2:53-54. Throughout her testimony, Cassin maintained that there was not a lot of activity in the lower portion because [i]t wasnt a very welcoming location, so [they] didnt go down there much. Tr. 2:53. Unlike the lower part of the yard, Cassin testified that the upper section was more heavily trafficked and used frequently as a patio area where they would often sit outside and have barbeques. Tr.

2:50, 53-54.

After she was conveyed the property from Cassin in 1998, Weinstein testified that she began planting and gardening in the lower portion of the yard. Around 2001, Weinstein built a stone wall up against the fence that created a garden border within the lower part of the Strip that continues to be maintained. Tr. 1:174, 176, 178-180, 192. Like Cassin, The Amentolas have continued to maintain a patio in the upper area of the backyard, filled with shrubs they planted along the fence, and where they sit and barbeque. Exhs. 17-19, 23-24; Tr. 1:174, 178-180, 186-187, 192, 195; 2:64, 68, 72-73.

Weinsteins use of the Strip has been actual, open, notorious, exclusive, and adverse. She has not, however, used this area for the required twenty years and cannot rely on her predecessors use to fulfill this period. Even assuming Salleys and Kerners use of the Strip was sufficient to satisfy the elements of adverse possession, Cassins use was not. Cassin repeatedly testified that her family did not frequently use the lower section of the yard and she did not present any testimony regarding use of the property up to the fence. Because Cassin is Weinsteins direct predecessor-in-interest, any tacking that could have come from Salleys and Kerners use of the Strip was cut off upon Cassins possession of the Weinstein Property and nonuse of the Strip. Based on this evidence, the Amentolas have not satisfied their burden of proving ownership of the Strip by adverse possession.

C. The Amentolas Partition Fence Claim

The Amentolas final argument is that Saleras fence is a partition fence and that both neighbors share equally in the maintenance or alteration of this fixture. I find this argument is without merit.

Where a fence is built by the owners of adjoining lands on their division line, the adjoining landowners own the fence as tenants in common. See Ropes v. Flint, 182 Mass. 473 , 473-475 (1903). The general duty to maintain a partition fence is declared in G.L. c. 49, § 3 (The occupants of adjoining lands enclosed with fences shall, so long as both of them improve the same, maintain partition fences in equal shares between their enclosures.). Under such circumstances, the landowners are liable to one another for removing, destroying, or injuring any part of the fence, and may not arbitrarily remove or destroy it except for the purpose of repair or rebuilding. See Deane v. Garniss, 294 Mass. 221 , 224-225 (1936); Newell v. Hill, 2 Met. 180 , 182-183 (1840).

I find that Saleras fence is not a partition fence. The general rule is that where a fence separating the lands of adjoining owners is entirely on the land of one, he or she has a right to alter, remove, or rebuild such fence. See Jubilee Yacht Club v. Gulf Refining Co., 245 Mass. 60 , 62 (1923); Kennedy v. Owen, 131 Mass. 431 , 432 (1881) (denying recovery for cost to rebuild partition fence where the fence was not built upon the line which divides the premises of the parties). This rule applies regardless of whether the division fence was erected by such owner or someone else. Pursuant to my earlier finding that the record boundary line is located at the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property, Saleras fence is entirely on the Salera Property. Moreover, the Amentolas have presented no evidence of an agreement or behavior of the parties or their predecessors suggesting that they intended to treat Saleras fence as a partition fence.

Conclusion

The record boundary line between the Subject Properties is located at the southerly boundary of the Weinstein Property as described by metes and bounds in their chain-of-title and shown on the 1922 Plan referenced therein. The entirety of the fence, which I find was built and is owned by Salera, is located on the Salera Property. The Amentolas have not established ownership of the Strip through adverse possession. I further find that Saleras fence is not a partition fence. Judgment shall enter on Counts I and II of the complaint declaring the record boundary line of the Salera property, dismissing Count III without prejudice, and dismissing the Amentolas counterclaims with prejudice. [Note 4]

Judgment accordingly.

LINDA A. SALERA v. LAURI WEINSTEIN, a.k.a. LAURI WEINSTEIN AMENTOLA, and DAVID AMENTOLA.

LINDA A. SALERA v. LAURI WEINSTEIN, a.k.a. LAURI WEINSTEIN AMENTOLA, and DAVID AMENTOLA.