If good fences make good neighbors, sometimes bad fences can ruin a neighborly relationship. Here, it is not a fence at issue, but a stone wall. The plaintiffs, Aldric Serrano and Elizabeth Covino allege that their next-door neighbors, the defendants, Kieran and Catherine Brosnan (Brosnans), encroached on their property by placing fill against a stone wall that runs the 135-foot length of the common boundary between the plaintiffs and the defendants properties, thereby improperly putting the plaintiffs wall into service as a retaining wall, without permission, to facilitate a change in grade on the Brosnans property. The Brosnans brought a counterclaim contending that the stone wall is in fact encroaching on their property, thereby giving them the right to place fill against it, and that the wall was functioning as a retaining wall at the time they purchased their property. Alternatively, the Brosnans claim that even if the wall is not on their property and their placement of fill encroaches on the Serrano-Covino Property, the extent of the encroachment is so insignificant as to be de minimis as a matter of law, or was done with permission of the plaintiffs given in consideration for the Brosnans not building their own retaining wall, which would have run parallel to the stone wall. Conversely, Mr. Serrano and Ms. Covino contend that if the wall encroaches on the Brosnans property, the encroachment similarly should be determined to be de minimis. For the reasons stated below, I find that the stone wall encroaches onto the Brosnans property, but that the extent of the encroachment is de minimis, and I decline to issue injunctive relief ordering the removal of the encroachment.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On March 19, 2014, the plaintiffs filed their complaint in this action alleging claims for declaratory judgment (Count I), trespass (Count II), negligence (Count III), nuisance (Count IV), and injunctive relief (Count V), all relating to the placement by the Brosnans of fill against the plaintiffs boundary line fieldstone wall. On April 9, 2014, the Brosnans filed Defendants Answer and Counterclaim. On April 22, 2014, the court (Grossman, J.) denied the plaintiffs request for preliminary injunctive relief. The Brosnans counterclaim, as later amended, included six claims: injunctive relief with respect to drainage in violation of the State Building Code (Count 1), G. L. c. 40A, §§8, 15, and 17 zoning enforcement (Counts 2 and 3), declaratory judgment (Count 4), trespass (Count 5), and injunctive relief with respect to the stone wall (Count 6). The plaintiffs and the Brosnans filed Cross Motions for Summary Judgment on July 31, 2015. Following a hearing on October 29, 2015, on November 9, 2015 I issued an Order on Motions for Summary Judgment, denying the Brosnans motion for summary judgment and allowing the plaintiffs motion in part. The Order dismissed Counts 2 and 3 of the Brosnans amended counterclaim and held that the remaining claims could not be resolved at the summary judgment stage.

A trial was held before me on April 5-7, 2016. Following the filing by the parties of post- trial submissions on July 1, 2016, I took the matter under advisement.

FACTS

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence admitted at trial, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, weight and inferences reasonably to be drawn from the evidence admitted at trial, I make factual findings as follows:

The Properties

1. The plaintiffs Aldric Serrano and Elizabeth Covino, husband and wife, have owned and resided at the property at 88 Hillcrest Parkway in Winchester (the Serrano-Covino Property) since 1994. [Note 1]

2. From September 2004 to February 2007, the plaintiffs demolished the existing dwelling on the Serrano-Covino Property and constructed a new home, including a new driveway, landscaping, and a fieldstone wall along the common boundary with the Brosnan property (Stone Wall). [Note 2]

3. The cost of constructing the Stone Wall was approximately $30,000.00. The Stone Wall is a freestanding, double-sided fieldstone wall installed along the length of the parties shared boundary line, for approximately 135 feet. Serrano and Covino built the wall to be ornamental and to achieve a certain aesthetic effect regarding their house and property. It was the long-term intention of the plaintiffs to keep the face of the Stone Wall facing the abutting property exposed for aesthetic reasons. [Note 3]

4. The Brosnans, husband and wife, purchased the property at 86 Hillcrest Parkway in Winchester (Brosnan Property) in 2011. The Brosnan Property abuts, and is to the east of, the Serrano-Covino Property. [Note 4]

5. The original grade of the Brosnan and Serrano-Covino Properties adjacent to both sides of the Stone Wall built by the plaintiffs dropped off from the front of the properties, so the wall increased in height toward the rear of the properties to a height of about 4 to 5 feet above the original grade as the properties sloped, measured from either side. [Note 5]

Location of the Common Boundary

6. The location of the Stone Wall in relation to the common boundary between the parties properties is at issue in this case. Serrano and Covino claim that the Stone Wall was built one inch inside (westerly of) their property line, while the Brosnans claim that the Stone Wall was built up to about two inches over (easterly of) the property line, thereby encroaching on their property.

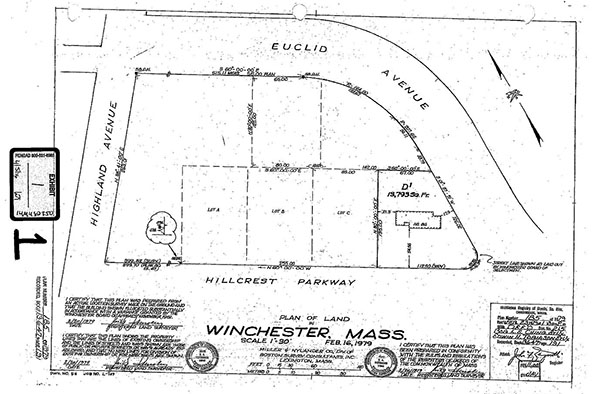

7. The earliest recorded plan of the subject properties presented by the parties (an original subdivision plan laying out the block was not offered by the parties) is entitled Plan of Land, Winchester, MA, dated December 18, 1936, prepared by John F. Sharon, recorded in the Middlesex Registry of Deeds Southern District (Registry) as Plan No. 55 of 1937 (1936 Plan). The 1936 Plan shows four lots fronting on Hillcrest Parkway to the south. Lot C, with 11,475 square feet of land and 85 feet of frontage on Hillcrest Parkway, is the now-Serrano-Covino Property. Lot D, a corner lot with 13,855 square feet of land, and 110 feet of frontage on Hillcrest Parkway and 125.67 feet of frontage on Euclid Avenue (both not including a dimension for the curve at the intersection), is the now-Brosnan Property. The plan shows the common boundary between lots C and D as being 135 feet in length. There are no monuments shown on the 1936 Plan. [Note 6]

8. The subject properties are also depicted on a plan entitled Plan of Land in Winchester, Mass., dated February 16, 1979, prepared by Miller & Nylander Co., recorded in the Registry on February 23, 1979 in Book 13647, Page 191, accompanied by a deed (1979 Plan). The 1979 Plan depicts the same four lots along Hillcrest Parkway as the 1936 Plan, with Euclid Avenue to the north and east, Hillcrest Parkway to the south, and Highland Avenue to the west. It identifies three stone bounds, two held along Euclid Avenue and one held in error (showing that it is 0.34 feet off the street line of Hillcrest Parkway and 0.76 feet off the westerly property line of Lot A) on Hillcrest Parkway. The now-Serrano-Covino Property is shown as Lot C, and the now-Brosnan Property is shown as Lot D1. Lot D1 is depicted as being 13,793 square feet (a discrepancy with the 1936 Plan not relevant here). The common boundary between Lots C and D1 runs northeasterly from Hillcrest Parkway for 135 feet. The 1979 Plan is attached to this decision as Exhibit A. [Note 7] The purpose of the 1979 Plan appears to have been to certify the location and setbacks of the house constructed on what is now the Brosnan Property.

9. The 1979 Plan contains a number of certifications, one of which reads, I certify that this plan was prepared from an actual location survey made on the ground and that the building shown is located substantially in accordance with the variance granted by the Winchester Board of Appeals November 1951. A second certification states, I certify that this plan shows the property lines that are the lines of existing ownership and the lines of streets and ways shown are those of public and private streets or ways already established and that no new lines for division of existing ownership or for new ways are shown. [Note 8] These certifications are signed by Fritz Petersohn, the Registered Land Surveyor who stamped the 1979 Plan. James Keenan, the plaintiffs expert witness in this case, and who was licensed as a professional land surveyor in 1982, was a member of the field crew for Miller & Nylander working on the survey to prepare the 1979 Plan.

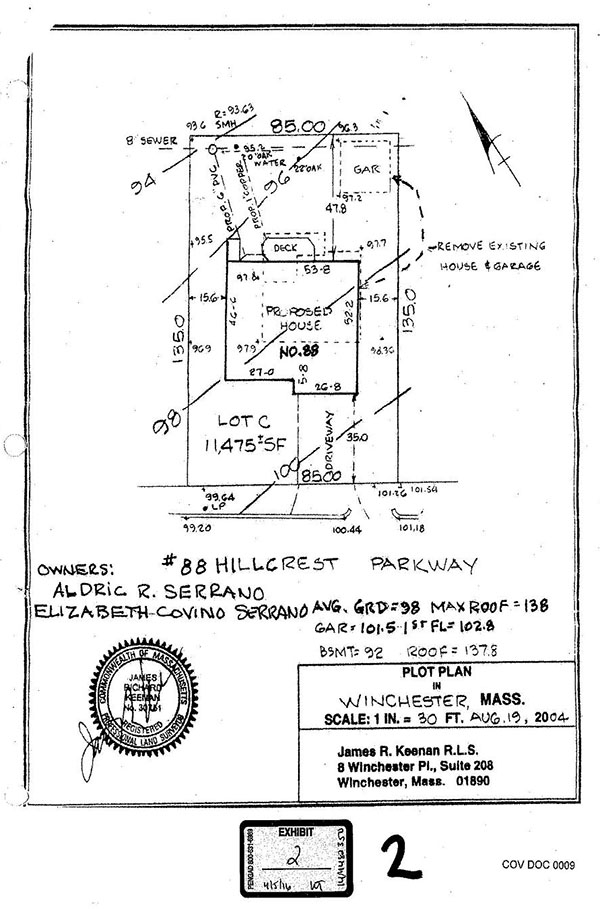

10. The next time Mr. Keenan visited the Serrano-Covino Property was in 2004, when he was hired by the Plaintiffs in preparation for construction of their new house. Mr. Keenan produced a plot plan of the property entitled Plot Plan in Winchester, Mass., dated August 19, 2004 (August 2004 Plot Plan). The August 2004 Plot Plan does not depict or reference any monuments, does not depict or reference abutting properties, and contains no certification other than Mr. Keenans stamp. The primary purpose of the August 2004 Plan was to show the setbacks for the proposed new house on the Serrano- Covino Property. I find that the August 2004 Plot Plan was not the result of an on the ground instrument survey, and I further find that it provides an insufficient basis upon which to draw any conclusion with respect to whether the property boundaries shown are accurately depicted with respect to proximity to other properties. The August 2004 Plot Plan is attached as Exhibit B. [Note 9]

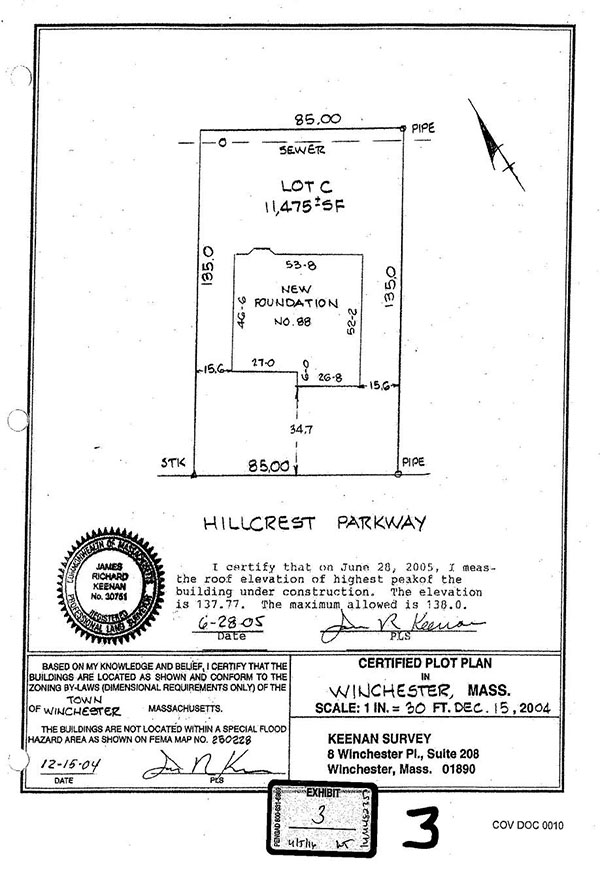

11. In December, 2004, after the foundation for the new house was completed, Mr. Keenan returned to the Serrano-Covino Property to prepare a second plot plan to show that the foundation had been accurately located with respect to the proposed setbacks. This plot plan is entitled, Certified Plot Plan in Winchester, Mass., dated December 15, 2004, prepared by Keenan Survey (December 2004 Plot Plan). The December 2004 Plot Plan includes no certification that it was the result of an on the ground instrument survey, and the plan does not contain any certification with respect to the accuracy of property boundaries depicted on the plan in relation to other properties. The only monuments shown or referred to on the plan are a pipe shown at each of the northeastern and southeastern corners of the property, where it abuts what is now the Brosnan property. This is the first appearance on any plan, recorded or unrecorded, of these two pipes, and there is no information on the plan as to how or when they were placed or with respect to the accuracy of their purported location on the property corners as depicted on the plan. I find that the December 2004 Plot Plan was not the result of an on the ground instrument survey, and I further find that it provides an insufficient basis upon which to draw any conclusion with respect to whether property boundaries are accurately depicted with respect to proximity to other properties. The December 2004 Plot Plan is attached as Exhibit C. [Note 10]

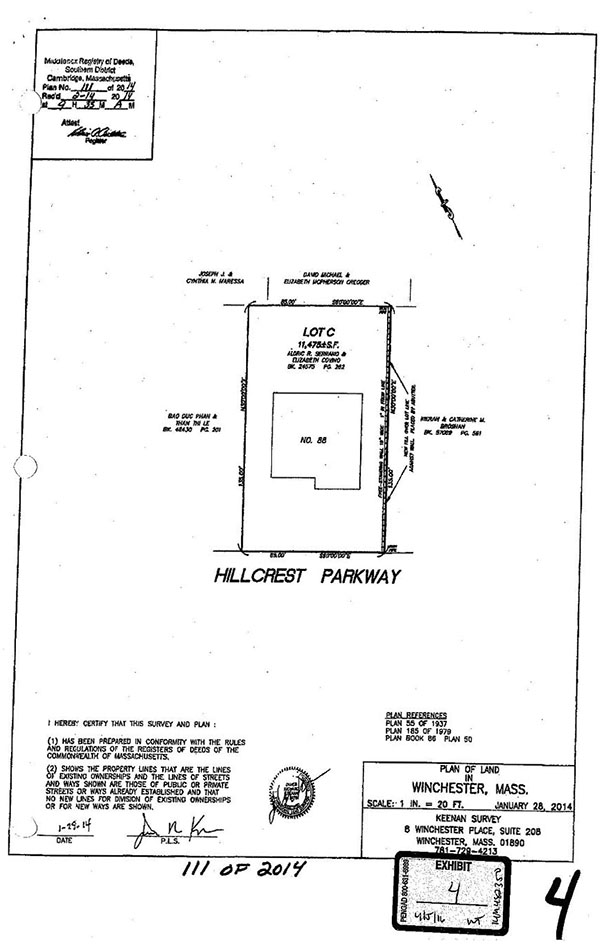

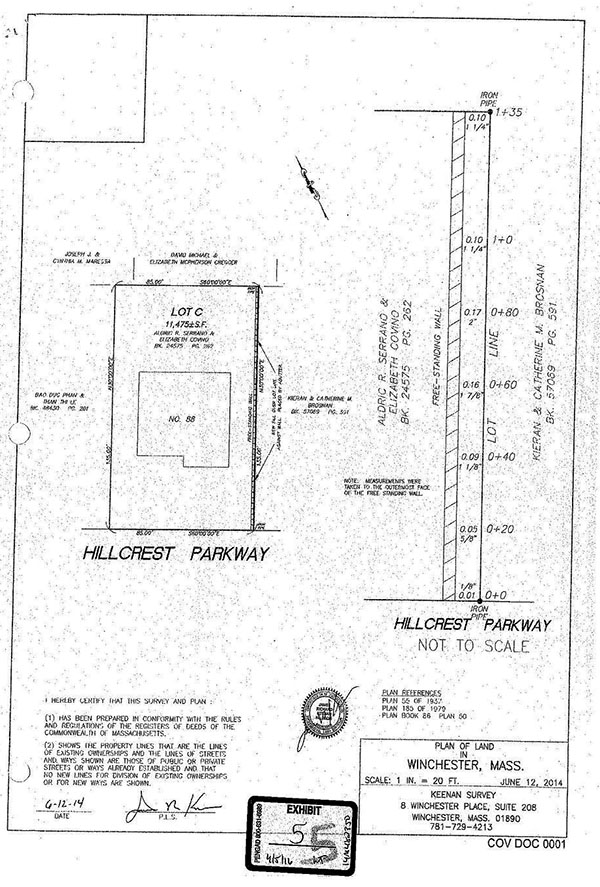

12. In conjunction with the present dispute, Mr. Keenan in January, 2014, prepared a plan entitled, Plan of Land in Winchester, Mass., dated January, 28, 2014, prepared by Keenan Survey (January 2014 Plan). The January 2014 Plan depicts the location of the Stone Wall in relation to the shared boundary between the Serrano-Covino Property and the Brosnan Property. The January 2014 Plan lists both the 1936 Plan and the 1979 Plan as plan references, and it contains Mr. Keenans certification that it shows the property lines that are the lines of existing ownerships. It does not contain a certification that it was prepared as the result of an on the ground instrument survey. The plan depicts the two iron pipes at the corners of the property, but does not show or refer to any other monuments. The January 2014 plan depicts the Stone Wall as being one inch, exactly, from the property line and entirely within the Serrano-Covino property for its entire length of 135 feet, and it further represents new fill over lot line against wall placed by abutter, which information was placed on the plan solely as a result of what Ms. Covino told Mr. Keenan and not as a result of any survey activity. The January 2014 Plan was recorded in the Registry on February 14, 2014 as Plan No. 111. I find that the January 2014 Plan was not the result of an on the ground instrument survey, its inaccuracy with respect to the distance of the Stone Wall from the common boundary was admitted at trial by Mr. Keenan, and I further find that it provides an insufficient basis upon which to draw any conclusion with respect to whether property boundaries are accurately depicted with respect to proximity to other properties or with respect to the proximity of the Stone Wall to the common boundary between the parties respective properties. [Note 11] The January 2014 Plan is attached as Exhibit D. [Note 12]

13. A subsequent plan prepared by Mr. Keenan is entitled Plan of Land in Winchester, Mass., dated June 12, 2014, prepared by Keenan Survey (June 2014 Plan. The June 2014 Plan, which serves as a demonstration of the inaccuracy of the January 2014 Plan, purports to depict the setback distance of the Stone Wall from the property line, within the Serrano- Covino Property, at twenty-foot increments and showing setbacks ranging from 1/8 of an inch to 2 inches. Like the January 2014 plan, this plan lists both the 1936 Plan and the 1979 Plan as plan references, and it contains Mr. Keenans certification that it shows the property lines that are the lines of existing ownerships, but also, like the January 2014 Plan, it does not contain a certification that it was prepared as the result of an on the

ground instrument survey, and in fact the setback measurements of the Stone Wall from the property line were determined by running a steel tape between the two iron pipes, the location of neither of which was properly verified, and by measuring the distance of the wall from the tape. Like its predecessor plans prepared by Keenan Survey, this plan does not identify or refer to any monuments on a recorded plan. I find that the June 2014 Plan was not the result of an on the ground instrument survey, and I further find that it provides an insufficient basis from which to draw any conclusion with respect to whether property boundaries are accurately depicted with respect to proximity to other properties or with respect to the proximity of the Stone Wall to the property boundary between the parties respective properties. I credit that the June 2014 Plan accurately depicts the distance of the Stone Wall from a line drawn between the two iron pipes, but I do not credit that the line between the two iron pipes is the property boundary. The June 2014 Plan is attached as Exhibit E. [Note 13]

14. In 2011, the Brosnans engaged George Collins, a professional land surveyor, to produce a plan of their property for the purpose of locating a proposed addition to the existing dwelling on the property, and again in 2014 to prepare a survey plan for the purposes of the present litigation. Specifically, Mr. Collins was asked to produce a plan showing the relation of the Stone Wall to the common boundary line.

15. In producing the survey of the Brosnan Property, Mr. Collins testified that he relied on monuments identified in the recorded 1979 Plan.

16. Specifically, Mr. Collins located three monuments shown on the 1979 Plan two stone bounds held on Euclid Avenue and one stone bound shown in error on Hillcrest Parkway, its location shown to be off by 0.34 that were used to establish the location of the common boundary. Collins also found several iron pipes in the vicinity of the boundary of the Brosnan Property, including the two iron pipes used in the Keenan plans, to which he gave no weight because they were not shown on any previously recorded plan. In completing the survey, Mr. Collins relied primarily on the two stone bounds held on Euclid Avenue as accurate monuments, since they were shown on prior recorded plans with no errors. [Note 14]

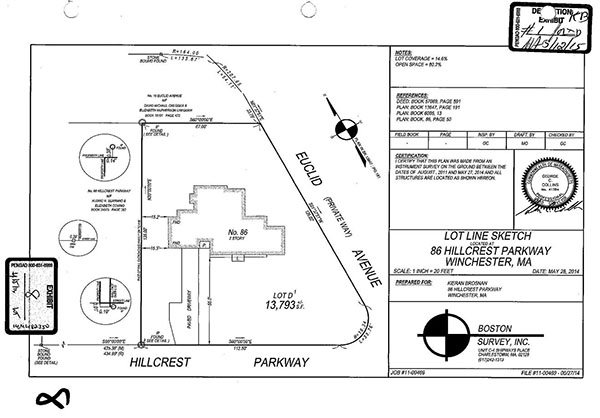

17. The resulting plan is entitled, Lot Line Sketch Located at 86 Hillcrest Parkway, Winchester, MA, dated May 28, 2014, prepared by Boston Survey, Inc. (the Collins Survey). The Collins Survey references the 1936 Plan and the 1979 Plan and an accompanying deed. It contains a certification that the plan was made from an instrument survey on the ground between the dates of August 2011 and May 27, 2014 and all structures are located as shown hereon. The Collins Survey is attached as Exhibit F. [Note 15]

18. The Collins Survey locates the common boundary between the Serrano-Covino Property and the Brosnan Property by utilizing the two stone bounds along Euclid Avenue, and by disregarding the two iron pipes. The Collins Survey thus locates the boundary line with reference to monuments whose locations can be verified, and it locates the iron pipes with respect to their proximity to the actual boundary line. According to the Collins Survey, which I credit as being accurate, the common boundary is located 0.19 feet westerly of the iron pipe at the front of the properties (at the street line), and 0.14 feet westerly of the iron pipe at the rear of the properties, as contrasted with Mr. Keenans conclusion that the iron pipes are located on the property line. The Collins Survey places the Stone Wall 0.12 feet, or just under one and one-falf half inches, over the common boundary onto the Brosnan Property at the street line, and does not specifically locate the Stone Wall at any other point, except to state that the Stone Wall encroaches partly on to #86. Extrapolating from Keenans June 2014 Plan, which accurately places the face of the Stone Wall 0.10 feet westerly of the iron pipe at the rear of the properties, the Stone Wall encroaches 0.04 feet, or just under half an inch, onto the Brosnan Property at the rear. Thus, the Stone Wall encroaches at least partly on the Brosnan Property, but it does so by an average encroachment of just under one inch. [Note 16]

Findings Relevant to Equitable Considerations

19. There was conflicting testimony at trial concerning whether the Plaintiffs gave, or did not give, permission to the Brosnans to place fill against the Stone Wall as part of their regrading project on their property. Given my finding that the wall encroaches on the Brosnan Property, and given my finding (see below) that the encroachment is de minimis and does not require the removal of the wall, it is unnecessary for me to resolve this factual dispute.

20. The construction of the Stone Wall over the boundary and encroaching on the Brosnan Property by a distance of just under one and one-half inches at the front of the properties ranging to just under one-half inch at the rear, was unintentional, and was a result of reliance on the incorrectly placed iron pipes as evidence of the location of the corners of the properties.

21. There was no credible evidence presented at trial of any damage to the Brosnans property as a result of the average encroachment of less than one inch of the Stone Wall onto their property. I find that, conversely, the Brosnans have in fact derived a benefit from the encroachment, by using the encroaching wall to support the change in grade of their property that they implemented in 2012 by placing fill against the wall.

22. Plaintiff Kieran Brosnan testified that it is the intention of the Brosnans to remove the fill they placed against the Stone Wall and build their own retaining wall parallel to the Stone Wall regardless of the outcome of this action. I find that the existing Stone Wall does not materially interfere with such proposed construction, as a new wall would have to be set back sufficiently from the common boundary so as to permit its construction and maintenance, entirely on the Brosnan Property, and the less than one inch average encroachment of the Stone Wall would not impede such construction. [Note 17]

DISCUSSION

The location of a common boundary, lying between the Serrano-Covino Property and the Brosnan Property, is the core issue in the instant matter. The location of a disputed boundary line is a question of fact to be determined on all the evidence, including the various surveys and plans, and the actual occupation and use[s] by the parties, where the true line originally ran. Ellis v. Ashwood Realty, LLC, 19 LCR 520 , 523 (2011), quoting Hurlbut Rogers Mac. Co. v. Boston & Maine R.R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). Monuments, when verifiable, are thus the most significant evidence to be considered, and control over the use of courses and distances. Ouellette v. McInerney, 19 LCR 41 , 42 (2001); see Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004). When presented with expert surveying and title testimony, a court must assess the opinions offered. The court must decide which...expert it finds more credible, basing such

assessment on the experts analysis, taking into account the other evidence presented, including the documentary evidence, particularly the deeds and plans that lend support and corroboration to each opinion. Lombard v. Cook, 20 LCR 325 , 326 (2012). "No surveyor or court has authority to alter or modify a boundary line once it is created. It can only be interpreted from the evidence of where that boundary is located." C.M. Brown, et al., Brown's Boundary Control and Legal Principles § 2.6 at 32 (4th ed., 1995) ("Brown's Boundary Control"). The law, however, does not require absolute certainty of proof to determine a boundary line, but merely a preponderance of the evidence. See McCarthy v. McDermott, 18 LCR 405 , 406 (2010), citing M. Brodin and M. Avery, Handbook of Massachusetts Evidence (8th Ed.), § 3.3.2(a) at 67.

Plaintiffs Serrano and Covino argue, based on their surveyor James Keenans 2014 plans, that the Stone Wall is on the Serrano-Covino Property and, therefore, the fill the Brosnans placed against the wall is encroaching on their property. The Brosnans contend that Mr. Keenans plans are unreliable because they lack essential information required of surveyors pursuant to 250 CMR 6.02, the regulations governing surveys of lines affecting property rights, and, even considered in conjunction with Mr. Keenans testimony, are insufficient to establish the location of the disputed boundary. I agree with the Brosnans, and for the following reasons, find Mr.

Keenans plans unreliable.

Surveyors must follow certain requirements prescribed by the Procedures and Standards of Land Surveying when producing surveys of lines affecting property rights. 250 CMR 6.00. [Note 18] They must [i]dentify the current record of the subject parcel and all abutting parcels thereto by title reference and [d]elineate both directly and indirectly measured quantities describing surveyed lines and points with significant figure and decimal place values appropriate to commonly accepted accuracy requirements for such surveys and to provide an adequate means of accurately reproducing said lines or points. 250 CMR 6.02(7)(a)-(b). Surveyors must also:

(c) Report the area of each surveyed parcel in appropriate units of measure and number of significant digits to express the value accurately.

(d) Reference other pertinent surveys of record describing the subject premises and any abutting premises.

(e) Provide references to the key Evidence used to base conclusions.

(i) Clearly distinguish between monuments found and monuments set along with their physical composition and description, which includes their mathematical relationship to the property.

(j) Provide sufficient course and distance redundancy to allow testing for mathematical correctness for the outbounds of the subject property and each parcel contained within the subject property.

(k) Report the actual observed measurements (either directly and/or indirectly) that describe the Evidence appearing on the survey and parenthetically show record measurements for comparison, when appropriate.

(l) Provide a vicinity map or reference the subject property to well-known geographic features, such as street intersections, rivers, or railroads.

(m) Show location of objects (e.g., streams, fences, structures) that are informative as to the general location of the boundaries of the property.

250 CMR 6.02(7).

The various plans produced by Mr. Keenan fail to incorporate many of the elements required by 250 CMR 6.02(7), and their absence renders the plans unreliable for the purpose of determining the correct location of the boundary between the parties properties. The 2004 plans and 2014 plans produced by Mr. Keenan do not clearly distinguish between monuments found and monuments set, along with their physical composition and description, which would include their mathematical relationship to the subject property. The Keenan plans do not report actual observed measurements or show record measurements for comparison, when appropriate. There is no indication of when, or if, an on the ground instrument survey was done to gather measurements in connection with these plans. Though Mr. Keenan testified that he relied on the 1936 Plan and 1979 Plan and references five stone bounds and three or four pipes that he found in the area around the disputed boundary, he never identified a stone bound on any of his plans. None of the plans show the distance between the Serrano-Covino Property lines and any monument other than the iron pipes Mr. Keenan opined are located on the boundary line itself. In fact, the Serrano-Covino Property sits in isolation on all of his plans, unconnected and without reference to the surrounding properties and bounds. Mr. Keenan testified that he believed the iron pipes were set in place around the time the 1979 Plan was created, possibly by him, but he could not be sure, and he offered no demonstrable evidence as to the accurate placement of the iron pipes on the ends of the common boundary line between the parties properties. Mr. Keenan admitted that in determining the location of the common boundary, he favored the scenario that supported the iron pipes as marking the boundary line and disregarded others that did not support that conclusion. He testified that his rationale for choosing the scenario that best supported the iron pipes as the boundary was that he could find no overwhelming evidence to reach a different conclusion.

Mr. Keenan relied on the accuracy of the location of the iron pipes to determine the location of the common boundary notwithstanding: that the pipes are not shown on any recorded plan; that he thinks he may have set the pipes, but cannot say for sure; that he offered no testimony as to how the iron pipes were set or when they were installed; he testified (without showing it on the plans) that he confirmed the accuracy of their location on the boundary by tying them in to the stone bounds shown on the recorded plans, but then he questioned the accuracy of the location of the stone bounds as a reason for relying on the iron pipes; and he admitted that using the stone bounds to determine the location of the common boundary produces different results, by up to a couple of inches, than using the iron pipes. [Note 19] Mr. Keenan admitted that this was a result-oriented exercise: he set out to confirm that the iron pipes were an accurate indication of the boundary line, and he discarded other scenarios, including use of the stone bounds shown on previous recorded plans, in order to achieve this result. [Note 20] Keenan further acknowledged that the iron pipes, whatever their original location, may have moved, and he could not confirm that they had not moved since he did his work at the Serrano-Brosnan Property in 2004. [Note 21] Despite testimony that the January 2014 Plan and the June 2014 Plan tied in the location of the iron pipes to the stone bounds, there is no reference to any of the stone bounds on the January 2014 Plan. I do not credit that the location of the iron pipes actually was confirmed by tying in to the location of the stone bounds, where the stone bounds are not indicated on the plan. Moreover, the admission at trial that what is represented on the January 2014 Plan as a consistent one inch setback of the Stone Wall from the common boundary was only an approximation, calls into question the veracity of both plans relied on by the plaintiffs with respect to a determination of the location of the common boundary. [Note 22] The plaintiffs, thus, have failed to present credible evidence of the location of the common boundary between their property and the Brosnan Property.

The Brosnans, however, have offered satisfactory evidence of the precise position of the common boundary, establishing that the Stone Wall is actually encroaching upon the Brosnan Property. In 2011, the Brosnans engaged surveyor George Collins to prepare a plan of their property. Collins produced a plan as a result of a retracement survey using on the ground measurements and locating substantial monuments, including the original controlling stone bounds found in the 1979 Plan two stone bounds held on Euclid Avenue and one stone bound shown in error on Hillcrest Parkway (meaning its location is off, but by an ascertainable measurement). Mr. Collins testified that he relied on the two stone bounds held on Euclid Avenue as accurate monuments since they were shown on prior recorded plans with no errors.

Although Mr. Collins, like Mr. Keenan, found several iron pipes near the boundary line, he gave them no weight because they were not shown on any record plans. Using the stone bounds along Euclid Avenue, Mr. Collins was able to match up the property lines and distances from prior recorded plans. In 2014, Mr. Collins produced a plan showing monuments found in the original plan, using them to determine the boundary line and the boundary lines relation to the Stone Wall, as well as the location of the iron pipes and their proximity to the boundary line. He testified that he depicted the boundary line in the most favorable possible position to the plaintiffs. The Collins Survey references the 1936 Plan and 1979 Plan and deed, and contains a certification detailing when an on the ground instrument survey was completed and the measurements taken. Based on findings depicted on the Collins Survey, the common boundary line is 0.19 feet westerly of the iron pipe at the front (street line) and 0.14 feet westerly of the iron pipe at the rear of the properties, which places the Stone wall 0.12 feet over the line onto the Brosnan Property at the front and 0.04 feet over the line at the rear.

I credit the Collins Survey and Mr. Collins testimony as persuasive and supported by the weight of the evidence. In doing so, I also find that the plaintiffs Stone Wall encroaches on the Brosnan Property. Because an encroachment has been established, the burden to the encroaching party of removing the encroachment against the harm to the other party for being permanently deprived of the use of their land must be weighed to determine whether the encroachment should be removed or is de minimis.

The Brosnans maintain that the Plaintiffs are judicially estopped from asserting that their encroachment is de minimis, but I do not find this argument persuasive. Judicial estoppel is an equitable doctrine that precludes a party from asserting a position in one legal proceeding that is contrary to a position it had previously asserted in another proceeding. Blachette v. Sch. Comm. of Westwood, 427 Mass. 176 , 184 (1998), citing Fay v. Federal Natl Mtg. Assn, 419 Mass. 782 , 787-788 (1995). The purpose of the doctrine is to prevent the manipulation of the judicial process by litigants. Canavans Case, 432 Mass. 304 , 308 (2000). As an equitable doctrine, judicial estoppel is not to be defined with reference to inflexible prerequisites or an exhaustive formula for determining [its] applicability. New Hampshire v. Maine, 532 U.S. 742, 751 (2001). Rather, the doctrine is properly invoked whenever a party is seeking to use the judicial process in an inconsistent way that courts should not tolerate. East Cambridge Sav. Bank v. Wheeler, 422 Mass. 621 , 523 (1996). Application of the equitable principle of judicial estoppel to a particular case is a matter of discretion. Otis v. Arbella Ins. Co., 443 Mass. 634 , 639-640 (2005), citing New Hampshire v. Maine, supra, 532 U.S. at 750.

The Brosnans argue that because the plaintiffs five-count complaint rested on the allegation that an encroachment by the Brosnans of one inch was not de minimis and entitled them to injunctive relief, the plaintiffs are now estopped themselves from arguing that their own encroachment of about an inch is de minimis and that therefore injunctive relief is not justified. However, these are not contrary legal postures. They involve two possible encroachments: the Brosnans fill encroaching upon the Serrano-Covino Property and the plaintiffs Stone Wall encroaching on the Brosnan Property. Although the claim and defense used by the plaintiffs both involve a determination whether the encroachment is de minimis, the factual determination whether to grant injunctive relief depends on an assessment of different facts and a separate balancing of equities. Because the encroachments are distinguishable, the positions taken by the plaintiffs are not inconsistent and they are not judicially estopped from arguing that an order of removal would be inequitable.

The test for whether a particular claim of trespass entitles a property owner to injunctive relief requires an examination by the court that depends very much on the particular facts and circumstances disclosed. Peters v. Archambault, 361 Mass. 91 , 93 (1972). Whether the encroachment is physically trivial, typically up to a few inches, is only one of the factors to be considered by the court. The court may also consider whether the cost of removing the encroachment is greatly disproportionate to the benefit to the plaintiff from removing it...and whether the encroachment is intentional or the result of negligent construction...Thus, it is proper, when considering whether a case comes within a particular exception, for the court to engage in a balancing of equities after due consideration of all pertinent facts. Capodilupo v. Vozzella, 46 Mass. App. Ct. 224 , 227 (1999). In making this factual inquiry, the court is to draw the line at permanent physical occupations amounting to a transfer of a traditional estate in land. Goulding v. Cook, 422 Mass. 276 , 277-278 (1996). The reason for this is that our law simply does not sanction this type of private eminent domain. Id., at 278, quoting Goulding v. Cook, 38 Mass. App. Ct. 92 , 99 (1995) (Armstrong, J., dissenting).

Under the facts present here, I find that this case fits into a category of exceptional cases where an order of removal is not mandated. Capodilupo v. Vozzella, supra, at 226. Even more so than the 4.8 inches found to be de minimis in Capodilupo, the encroachment of the Stone Wall onto the Brosnan Property is exceptionally de minimis, averaging less than one inch. The burden on the plaintiffs of removing the wall is wholly disproportionate to the benefit the Brosnans would receive in having it removed. The cost to remove the Stone Wall would be approximately $12,000.00, [Note 23] and the cost to rebuild it entirely on the Serrano-Covino Property would be several times that amount. While there was testimony at trial demonstrating that the fill placed by the Brosnans against the wall is damaging the wall, which was not designed or built to be a retaining wall, the Brosnans offered no evidence as to how the wall is causing any damage to their property and offered no credible evidence as to how the wall interferes in any way with their use of their property. In fact the opposite is true: they utilize the wall to provide lateral support for the altered grade on their property, thus deriving a benefit from its presence, which is why they installed the fill against it in the first place. While they contend that they intend to build their own wall on their property, and that the existing wall will interfere with their intended placement of their new wall, I do not credit this testimony. Absent permission from the plaintiffs to enter onto their property for the purpose of constructing a new wall right at the property boundary, permission which, given the relations between the parties is unlikely to be forthcoming, the Brosnans will have to set a new wall sufficiently back, presumably at least about two feet, from the common boundary so as to facilitate convenient and practical access to it for construction and maintenance, entirely on their property. The average encroachment of the existing wall of under one inch onto their property will not interfere with this process.

In making the determination that the slight encroachment of the wall onto the Brosnan Property will not interfere with the Brosnans use of their property in any material way, I am mindful of the admonition in Goulding v. Cook that our law simply does not sanction this type of private eminent domain. 422 Mass. at 278. However, this case is readily distinguishable from the facts in Goulding, in which the offending parties intentionally appropriated nearly 3,000 square feet of their neighbors land to install a septic system they did not have room for on their own property. Here, by contrast, the encroachment was innocent, the encroachment is a truly de minimis encroachment averaging under one inch, and it is an encroachment that has actually benefitted (by providing lateral support) rather than interfered with the neighbors land.

Moreover, given, as I find, that the encroachment of the wall onto the Brosnan Property was unintentional and the result of faulty surveying, I find it inequitable to order the plaintiffs to remove the wall. At all relevant times, the plaintiffs believed that the iron pipes marked the boundary line and that they owned the land under the Stone Wall. They relied on the plans provided by Mr. Keenan that showed the iron pipes located on the line itself, and placed the wall so as not to reach over the (incorrect) line formed by the two iron pipes.

CONCLUSION

I find and rule that the Collins Survey accurately depicts the boundary between the Serrano-Covino Property and the Brosnan Property. The Stone Wall encroaches on the Brosnan Property, but the encroachment is de minimis, was unintentional, and the burden to the plaintiffs of removing the encroachment far outweighs the burden to the Brosnans of allowing it to remain. Judgment will enter against the plaintiffs, dismissing the plaintiffs complaint, and in favor of the Brosnans on Counts 4 and 5 of their amended counterclaim. However, because I find the encroachment to be de minimis, the plaintiffs are not required to remove the wall, and judgment will enter against the Brosnans on Count 6 of their amended counterclaim, seeking injunctive relief. Further, although not addressed at trial or in the parties post-trial submissions, the Brosnans remaining Count 1 of the amended counterclaim is dismissed without prejudice for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. [Note 24]

Judgment accordingly.

ALDRIC SERRANO and ELIZABETH SERRANO v. KIERAN BROSNAN and CATHERINE BROSNAN

ALDRIC SERRANO and ELIZABETH SERRANO v. KIERAN BROSNAN and CATHERINE BROSNAN