Introduction

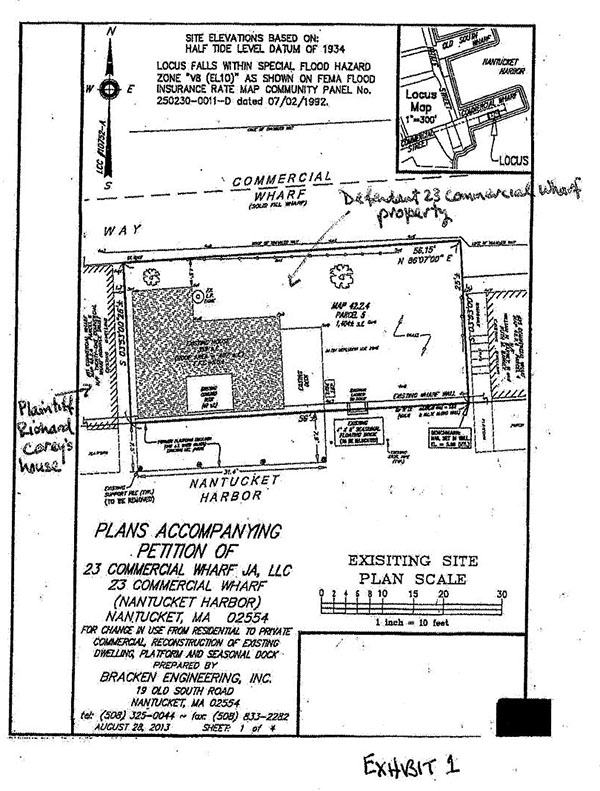

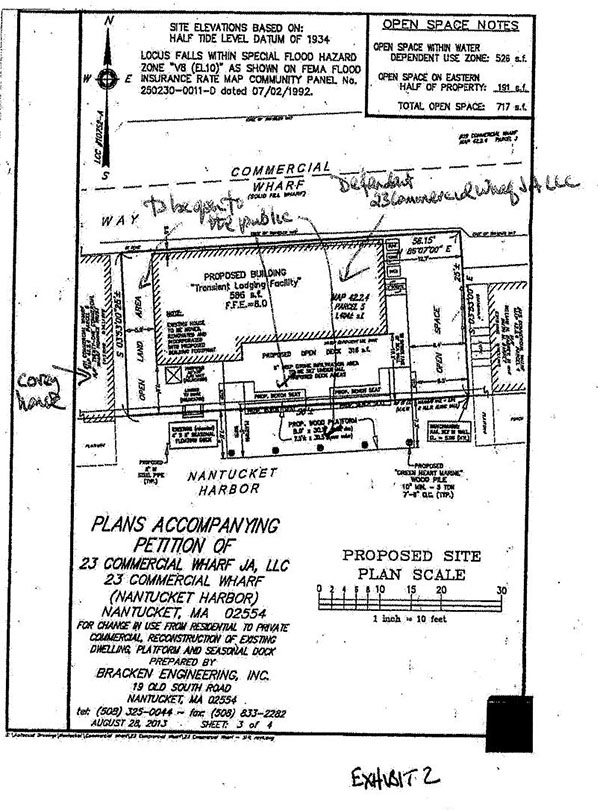

This case concerns the proposed expansion and conversion of a small, non-conforming, one-story residential cottage on the quiet side of Commercial Wharf in Nantucket Harbor recently purchased by defendant 23 Commercial Wharf J.A. LLC, and pre-existing and thus protected in its existing form (see Ex. 1: Existing Site Plan) into a significantly larger, two- story commercial transient cottage with (1) a new, second story and a ground-level footprint nearly two-thirds bigger than the existing structure, (2) a deck and platform over the harbor that, formerly private and serving only the small, existing cottage, would now be open to all members of the public at all hours, and (3) a passageway, that would also now be open to the public at all hours, which provides the publics sole access to that deck and platform and is only 1.2 away from the wall of the abutting neighbors house at 21 Commercial Wharf (see Ex, 2: Proposed New Site Plan). [Note 1] This expansion and conversion requires a special permit from the Nantucket Planning Board because it would change the use of the property from residential to commercial, the lot is substantially undersized (less than a third of what the bylaw mandates), and the lot coverage of the building, presently 25.5% of the total lot area and limited to no more than 30% by right, would now increase to 42%. Under the governing statute, G.L. c. 40A, §6, and the governing bylaw provisions, Bylaw §§139-33A(4) and 33E(2)(A), the special permit can only be granted if the expansion and conversion would not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the existing residential cottage and lot coverage.

The board found that there would be no such detriment, and allowed the special permit. Plaintiff Richard Corey, the owner of the abutting house at 21 Commercial Wharf, [Note 2] disagrees with that finding and brought this G.L. c. 40A, §17 appeal.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule that the proposed expansion and conversion of the existing residential cottage into a substantially larger and far more intrusive commercial transient cottage does not comply with the special permit provisions of Nantuckets zoning bylaw or the requirements of G.L. c. 40A, §6, and the boards decision to the contrary was unreasonable, arbitrary, and capricious because its finding that the expansion and conversion would not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood has no rational support in the evidence in this case. The boards decision granting the special permit is thus reversed and vacated.

The Standard of Review

This is a G. L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal from the grant of a special permit and, as in all such proceedings, the reviewing court hears the case, makes de novo factual findings based solely on the evidence admitted in court, and then, based on those facts, determines the legal validity of the municipal bodys decision (here, the planning board as the special permit granting authority) with no evidentiary weight given to any findings by the board. Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 485-486 (1999) (citing Bicknell Realty Co. v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 330 Mass. 676 , 679 (1953) and Josephs v. Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 ,

295 (1972)).

The validity of the boards decision is judged by a two-fold test. First, the court must determine whether the board acted in accordance with the proper standard or, instead, on a legally untenable ground. Roberts, 429 Mass. at 486. If the board applied the wrong standard, its decision must be vacated. Id. Second, even if the proper standard was applied, the court must ascertain, on the facts the court has found, whether the boards decision was unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary. Id. (internal quotations and citations omitted). If so, it must be vacated. Id. Conversely, if the two tests are met, the decision must be affirmed. Id.; see also Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers of New York Inc. v. Bd. of Appeals of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 380-383 (2009).

In determining whether the Councils decision was based on a legally untenable ground (the initial test), the court must determine whether it was decided

on a standard, criterion, or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws. Here, the approach is deferential only to the extent that the court gives some measure of deference to the local boards interpretation of its own zoning by-law. In the main, though, the court determines the content and meaning of statutes and by-laws and then decides whether the board has chosen from those sources the proper criteria and standards to use in deciding to grant or to deny the variance or special permit application.

Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003) (internal citations omitted).

In determining whether the decision was unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary (the second test), the question for the court is whether, on the facts the judge has found, any rational board could come to the same conclusion. Id. at 74. The judge should overturn a boards decision when no rational view of the facts the court has found supports the boards conclusion, and should also overturn it in situations when the reasons given by the board lacked substantial basis in fact and were in reality mere pretexts for arbitrary action or veils for reasons not related to the purposes of the zoning law. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership v. Bd. of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 475 (2012) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

Applicable Zoning Provisions

The 23 Commercial Wharf property is located on the south side of Commercial Wharf in Nantuckets Residential/Commercial Zoning District (RC District) and Harbor Overlay District (HO District). As such, to be conforming, it requires at least a 5,000 square foot lot and five feet minimum side and rear setbacks. Its 1,404 square foot lot, however, is less than one-third the minimum size, and the current structure on that lot a one story residential cottage with a 359 square foot footprint is only 0.6 feet from the lots rear boundary along Nantucket Harbor and 1.2 feet from its western side boundary alongside plaintiff Richard Coreys property (21 Commercial Wharf) next door. [Note 3] Both the 23 Commercial Wharf lot and the current structure, however, pre-date those zoning requirements and are thus protected (grandfathered), as they presently exist, under both G.L. c. 40A, §6 and the Nantucket zoning bylaw, §139-33A. These existing conditions are shown on the attached Ex. 1.

The new owner of 23 Commercial Wharf (defendant 23 Commercial Wharf J.A. LLC) wants to expand the present structure and change its use. Specifically, it wants to (1) re-locate the building further back from the rear and western side boundaries (the larger side setback on the west side would now become a five-foot wide open land area, and the waterside rear of the property would now be occupied by a large, 316 square foot ground-level open deck), (2) increase the buildings footprint by more than two-thirds to 586 square feet, (3) add a second story (there is currently only one), (4) construct the new 316 square foot ground-level waterside open deck referenced above, (5) construct a new 244 square foot platform over the harbor, connected to the new, on-shore waterside deck, in a location previously occupied by a former, no longer existing platform, and (5) change the use of the building from a residential cottage to a commercial transient cottage. As a condition of the Chapter 91 license that is needed to construct the new waterside deck and over-harbor platform, the deck, the platform, and the open land area along the Corey boundary and just 1.2 feet from Mr. Coreys house are required to be open to the public at all times. All of these areas are presently private, serving only the existing one-story residential cottage. The proposed new site plan is shown on Ex. 2.

Because the 23 Commercial Wharf lot is significantly undersized (less than one-third the required minimum), and the proposed increase in the new structures lot area coverage (from 25.5% to 42%) exceeds the 30% maximum allowed by right to lots having less than 5,000 square feet, [Note 4] these changes and extensions require a special permit from the Nantucket Planning Board. That permit may be granted only if the change, extension or alteration shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming use to the neighborhood. Bylaw, § 139- 33A(4); G.L. c. 40A, §6.

The Commercial Wharf Neighborhood

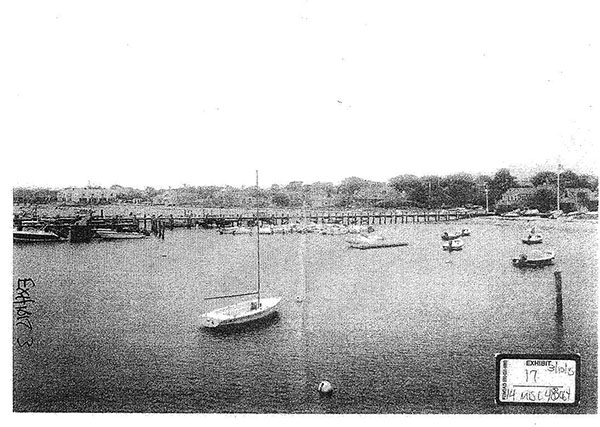

23 Commercial Wharf is located on the south side of Commercial Wharf, a privately- owned wharf on the edge of downtown Nantucket which extends into Nantucket Harbor. Commercial Wharf is the southernmost wharf in Nantucket town, with nothing but boat slips and a distant public boat docking pier (the dinghy dock) in the harbor to its south. See Ex. 3. The public presently has access to Commercial Wharf only along a brick walkway on its north side and over the cobblestone roadway in the center which dead-ends at the end of the wharf. There is currently no public access along the south side of the wharf where 23 Commercial, the Corey house, and their neighboring homes are located. Everything in that area is private. At the end of the wharf, beyond 23 Commercial and its neighboring properties, are a cluster of boat slips owned by Nantucket Island Resorts (NIR), as well as laundry and bathroom facilities primarily serving those boats. There is currently little or no vehicular traffic on the wharf except for the cars used by the residents and an occasional NIR service vehicle or cart. All of its parking spaces are private.

The buildings on Commercial Wharf are primarily small cottages, many of which are summer rentals owned by NIR. There are no restaurants, shops, or other businesses except for the NIR boat slips. Most of the NIR cottages are on the north side of the wharf, and they are connected by public passageways between those cottages. On the wharfs south side, at the point where the wharf begins, there is an NIR rental cottage known as the Meridian and then, going past that towards the end of the wharf, (1) a private residential cottage owned by the plaintiff Richard Corey (21 Commercial Wharf), (2) a single-story residential cottage at 23 Commercial Wharf (the property at issue in this lawsuit), and (3) a private residential cottage owned by William Barney (25 Commercial Wharf). Past this three-house cluster of private homes are two more NIR cottages and the NIR boat slips, ending at the tip of the wharf. NIR uses one of these cottages as a maintenance facility and for storage of the golf carts it uses to service its cottages on the wharf (to transport guests, pick up laundry and garbage, carry tools, etc.).

The private residence closest to the NIR boat slips 25 Commercial Wharf is a two- story cottage owned by William Barney, with a deck and covered porch overlooking the water. Mr. Barney rents out the cottage for two weeks each year, but his family generally occupies it continuously during the remainder of the summer and occasionally on weekends during the fall before it is closed for the season.

Mr. Coreys house at 21 Commercial Wharf is two-story cottage, with a widows walk on top and upper and lower decks. He and his wife purchased and prize it because of its location on the water and the privacy it offers it is on the far (south) side of the southernmost wharf in the town, its water side faces away from the busy downtown center, there is no lawful public access on either its east or west sides leading to the water, there is no lawful public access along its water side, and there is no lawful public access on its abutting neighbors sides leading to the water or along their water sides. The Coreys particularly enjoy the quiet, secluded nature of their back decks overlooking the harbor currently quiet and secluded even during the peak tourist times where it is common for Mrs. Corey to spend the majority of her days while on Nantucket. See Ex. 3. Like the Barneys, the Coreys mostly use their cottage during the summer and shoulder seasons.

The 23 Commercial Wharf Property, As Existing and Proposed

The residence between the Barney and Corey cottages 23 Commercial Wharf, the property at issue in this lawsuit was built in the early 1900s and, due to bad weather and neglect, has become increasingly dilapidated over time. Somewhat smaller than the neighboring Barney and Corey residences, the cottage is one story and approximately 359 square feet in area, with a deck on its east side and another, smaller one on the south, both overlooking the water. A platform that once extended from its south (waterside) edge over the water was destroyed in the 2012/2013 winter storms and has not been repaired or replaced.

23 Commercial Wharf was recently purchased by defendant 23 Commercial Wharf J.A., LLC, owned by James Apteker, who owns and manages a number of event spaces and resorts throughout southeastern New England. He currently has no other properties on the Island. Mr. Apteker was initially unsure whether he would use 23 Commercial Wharf as a personal vacation residence, but ultimately decided to renovate and expand it for use as a commercial rental property.

Under 23 Commercials proposed site plan, the existing cottage will be expanded, relocated, and incorporated within a new building footprint. See Ex. 2. With the addition of a second story, the cottage will increase in height from 14.1 feet to 24.3 feet. Its footprint will also increase from 359 square feet to 586 square feet. As the lot itself will maintain its current square footage and frontage, the ground cover ratio will increase to 42%. The cottage will also be moved seven feet to the north and 3.8 feet to the east, thus eliminating the current side and rear setback nonconformities. The new setback on the west (the Corey side), will now be the minimum allowable (5 feet). To the east and west of the cottage, open areas will extend to the lots eastern and western boundaries. A portion of the eastern lawn that is currently used for parking will remain available for use as a parking area. As discussed more fully below, the five- foot wide open space on the west will become a public-access corridor for the public to access 23 Commercials new rear deck and its new platform over the water. The western edge of that five- foot wide space will be just 1.2 feet from the edge of the Coreys house, directly under its bedroom window on that side, and there are no current plans (or planning board requirement) to put a fence or other barrier along it.

The exterior decks will be open and expanded to 316 square feet, with permanent benches installed along the waters edge. From the southern edge of the deck, a new 244 square foot wooden platform will extend over the water. Also, an existing four-foot by eight-foot floating dock will be relocated from the east side of the property to the west of the wood platform, towards the Coreys. The expanded deck and new over-water platform areas will be approximately fifteen or twenty feet from the Coreys bedroom window, and fewer than ten feet from their deck.

Importantly, for the first time ever, the passageway from the street to the water alongside the Corey home (the open land area shown on Ex. 2) will be expanded to become five-feet wide and it, the new deck and over-harbor platform on the 23 Commercial Wharf property, and the bench seats being installed on that deck and platform, will be open to the public. There are no restrictions on the publics hours of access.

23 Commercials architectural plans were designed to preserve as much of the existing structure as possible, including portions of the walls and roof. However, nearly everything must be re-located on the site, a new story added, and even the interior of the existing building completely rebuilt. The first floor will be reconfigured with a bathroom, bunk room, and great room containing a seating area, dining area, and full kitchen. The second story addition will have a second bathroom, as well as a bedroom. Construction will take approximately twelve months. The existing cottage will be lifted with hydraulic jacks, placed on cribbing, and moved to another portion of the site. The ground underneath the re-located and expanded structure will then be excavated by Bobcat machines, loaded onto trucks, and hauled away. A new foundation will then be constructed, onto which the cottage will be lowered. Construction workers will then use power hammers, generators and other mechanized tools to complete the renovations.

23 Commercial also proposes to convert the property from private residential to commercial use specifically, a full-time rental property. The Grey Lady Management Plan it presented to the planning board purported to detail its plans for the property, stating that it would be professionally managed by [a] reputable local operator, and is [c]urrently under the 76 Main umbrella. According to that submission, 76 Main a hotel on the Island would be managing the cleaning, maintenance, and guest check-in/check-out process, and the property would be listed on 76main.com. It purports to set standards for the rental rate and payment requirements, and to prohibit loud outside noise between 10 p.m. and 7 a.m., smoking, pets, off- site guest parking, and outside commercial functions. It purports to prohibit the idling of shuttle vehicles on the wharf, and to limit use of the proposed float to small, non-motorized craft. And finally, it purports to prohibit outside construction activity between May 15th and October 15th, to limit construction vehicle parking to within the property, and to regulate the use of heavy equipment and the removal of trash and construction debris.

The plan purports to do this, and the special permit was conditioned on compliance with its terms, but there is, in fact, no plan of any kind in place, written or oral, with 76 Main. Instead, all that exists is an informal understanding, not binding on either 23 Commercial or 76 Main, to enter into negotiations for a management agreement, no terms yet agreed, if and when 23 Commercials plans for the property are ultimately approved. According to Mr. Apteker, if no agreement is reached with 76 Main, Mr. Aptekers own event company, Longwood Events, intends to manage the property. Neither Longwood Events, nor any other Apteker-associated entity, currently have a presence, personnel, facilities, or experience on the Island, and it is unclear how, without such presence, personnel and facilities, they will enforce the outside noise, parking, idling, and watercraft use prohibitions the plan purports to set for rental tenants. It is even more unclear how the noise, smoking and pet prohibitions will, or even can, be enforced against members of the public walking through the access corridor alongside the Corey house and gathering on the 23 Commercial Wharf deck and over-harbor platform, with an unrestricted right to be there. Such public access, and the impacts it creates, is no small thing. However quiet in the off-season, Nantucket in the height of the tourist season, particularly in the downtown area, is far different. This neighborhood was described as essentially Figawi central during the Islands signature event, the Figawi Memorial Day weekend sailboat races, which draws a fairly rowdy crowd that part[ies] and drink[s] quite a bit and fans off after the tents close down and continue[s] drinking and celebrating into the night. It is fair to infer, and I so find, that at least a portion of that crowd will go to the available public waterside spaces to enjoy the views of the harbor. It is also fair to infer, and I so find, that even outside Figawi weekend, numerous visitors will soon learn of the public deck and harbor platform on the 23 Commercial Wharf property and go there to sit on its benches, picnic, and drink. The views that attract the Coreys and the other wharf residents will also attract outsiders, now with an express right of access.

The Special Permit

23 Commercial Wharf applied for a special permit to implement this proposal, and the planning board granted that application (including a waiver of the zoning requirement that the structure be located no closer than 25 feet from the mean high water line), based on a finding that the expansion and conversion will not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the existing residential cottage. It reached that conclusion based primarily on a finding that the Management Plan submitted by the Owner/Applicant for the proposed cottage will adequately protect the peace and quiet enjoyment of the neighbors by limiting noise, prohibiting pets, prohibiting guest parking and by providing for a scheduled maintenance, cleaning and upkeep of the Property. The fact that there was no such Management Plan either agreed or in place was not addressed (there is no indication that 23 Commercial disclosed this to the board) and, tellingly, the board did not address the impacts of public access, over which 23 Commercial Wharf would have little or no control. [Note 5] Indeed, as a key part of its decision, the board emphasized the significant public benefit that would result from public access to the open space on the eastern portion of the Property, and the open deck on the southerly side of the proposed cottage. The significance of this is discussed more fully in the Analysis section below, where further relevant facts are also set forth.

Analysis

Standing

Only a person aggrieved may challenge a decision of a zoning board of appeals or other special permit granting authority. Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996). See G.L. c. 40A, §17. Abutters are entitled to a rebuttable presumption of aggrievement. See 81 Spooner Road LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012). As a direct abutter to 23 Commercial Wharf, Mr. Corey is entitled to this presumption, which 23 Commercial can rebut in two ways. First, 23 Commercial may show that the rights allegedly aggrieved are not interests protected by G.L. c. 40A or the local zoning bylaw. See id. at 702. An abutter can have no reasonable expectation of proving a legally cognizable injury where the Zoning Act and related zoning ordinances or bylaws do not offer protection from the alleged harm in the first instance. Id. Second, if Mr. Corey alleges harm to an interest protected by the zoning laws, 23 Commercial can rebut the presumption by producing credible evidence to refute the presumed fact of aggrievement. See id. This can be done by presenting evidence showing the alleged aggrievement is either unfounded or de minimus. Id.

If the presumption of standing is rebutted, the burden to prove standing rests on Mr. Corey, who must establishby direct facts and not by speculative personal opinion that his injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community. Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 33 (2006). This requires an assertion and proof of a plausible claim of a definite violation of a private right, a private property interest, or a private legal interest. Harvard Square Defense Fund Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Cambridge, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 491 , 492-493 (1989). To assert such a plausible claim, a plaintiff must put forth credible evidence to substantiate his allegations. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. Credible evidence has both quantitative and qualitative components. See Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 441 (2005).

Quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made. Qualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the boards action. Conjecture, personal opinion, and hypothesis are therefore insufficient.

Id. (internal citations omitted).

Mr. Corey benefits from the presumption of aggrievement, and, in addition, has affirmatively shown sufficient aggrievement in at least two ways. First, he will be adversely affected by construction impacts, which will be significant and of long duration. Second, he will be adversely affected by the public use of the passageway immediately alongside his house, and of public use of the deck and over-harbor platform just feet away from his windows.

Standing may be established by evidence of intrusive constructive impacts. See Gale v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 331 , 335 (2011); Cornell v. Michaud, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 607 , 615 (2011). The re-location and expansion of the 23 Commercial cottage, as well as the construction of the new, expanded deck and the new over-harbor platform, are just feet away from Mr. Coreys cottage and will be extensive, noisy, and continuous for over a year. The existing cottage will be lifted and relocated to another location on the property, ground material will be excavated and hauled away in trucks so that a new foundation can be constructed, and the cottage will be moved again onto the new foundation. A second story will be added to the cottage, its decks will be expanded, and its interior will be completely renovated. This process will require the use of heavy machinery and other construction equipment such as power hammers and generators.

There is no question that such a substantial construction project would be disruptive to the surrounding properties. As 23 Commercials lot is merely 1,404 square feet in area and its existing cottage is just over one foot away from Mr. Coreys property, the impact upon Mr. Corey would be particularly intrusive. Therefore, on that basis alone, I find Mr. Corey has standing to appeal the Boards decision.

Standing is also conferred by the impacts of the public access required by the special permit decision. Those impacts, which I discuss in the context of the the merits of the boards decision, are as follows.

The Merits

Nantuckets zoning bylaw authorizes the special permit granting authority (in this case, the Planning Board) to issue special permits for structures and uses which are in harmony with the general purpose and intent of [the bylaw] subject to the provisions of [the bylaw]. Bylaw, § 139-30(A)(1). That bylaw provides that no extension or alteration of a preexisting, nonconforming structure or use shall be permitted unless (1) any change or substantial extension of such use complies with the zoning bylaw, (2) the special permit granting authority finds that such change, extension or alteration shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming use to the neighborhood, and (3) a special permit supported by such a finding is granted. See § 139-33(A)(1), (4)(a) & (4)(b). These provisions are in accordance with the statute governing modifications to preexisting nonconformities, G.L. c. 40A, § 6, which provides, in relevant part:

[a] zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to structures or uses lawfully in existence or lawfully begun . . . but shall apply to any change or substantial extension of such use, to a building or special permit issued after the first notice of said public hearing, to any reconstruction, extension or structural change of such structure and to any alteration of a structure begun after the first notice of said public hearing to provide for its use for a substantially different purpose or for the same purpose in a substantially different manner or to a substantially greater extent except where alteration, reconstruction, extension or structural change to a single or two-family residential structure does not increase the nonconforming nature of said structure. Pre-existing nonconforming structures or uses may be extended or altered, provided, that no such extension or alteration shall be permitted unless there is a finding by the permit granting authority or by the special permit granting authority designated by ordinance or by-law that such change, extension or alteration shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming use to the neighborhood.

Mr. Corey challenges the grant of the special permit on two grounds. The first is that the expanded cottage does not fit the definition of a transient residential facility and thus would not be an allowable use. [Note 6] I need not and do not reach this argument because I agree with Mr. Coreys second contention: that the proposed expansion and conversion, conditioned on the publics access to the passageway next to Mr. Coreys cottage and the deck and over-harbor platform just feet away from his and the other neighboring propertys windows, is substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the existing residential structure, and the boards finding to the contrary is not supported by any rational view of the facts.

The Boards approach does not comply with the law applicable to the expansion and conversion of non-conforming properties, particularly to this extent, in this way (conditioned on public access where none existed before), and on a lot this undersized with a building so close to its neighbors. The relevant inquiry is whether the expansion and conversion will be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the existing residential cottage. This it surely will. The test is not the benefit of having new, public areas along the water, available for viewing, picnicking, and fishing year-round, over-riding the significant adverse effects on the seasonal-resident neighbors. That type of inquiry and balancing is outside the scope of G.L. c. 40A, §6 and the Nantucket zoning bylaws provisions on the expansion of non-conforming uses.

The 23 Commercial Wharf property is currently a private cottage, all of whose areas are private. Its neighbors on both sides, plaintiff Richard Corey and Mr. Barney, are also private cottages, also entirely private. They are in tight proximity with each other, with currently less than 2 ½ feet between the wall of Mr. Coreys house and the wall of the present 23 Commercial Wharf cottage. There is currently no public access between them, and no public access along the waters edge anywhere on the Corey, 23 Commercial, or Barney lots. All this will change with the special permit. The area between Mr. Corey and 23 Commercial, while widened by 3 feet, will now become a public access corridor to a now-public deck and now-public over-harbor platform along the waters edge behind the expanded 23 Commercial cottage. The deck and platform are a short walk from the center of Nantucket. The view from that deck and platform is extraordinary. See Ex. 3. It is beyond question that that spot will soon become popular with the public. It will now have permanent benches, encouraging people to linger. And it will be popular for gatherings at all hours at sunrise, during the day, during the evening, and at night in numbers that will only expand as its location and public availability become increasingly known. What had been quiet and private before the public areas of Commercial Wharf are on the opposite (north) side of the wharf will no longer be so. Moreover, the deck and platform will be far larger than ever before, potentially holding far many more people.

The board believed that 23 Commercials Management Plan would sufficiently address all these impacts. Not so. Contrary to what the board apparently believed, there is no such plan in place, and no such plan agreed with 76 Main or anyone else. Mr. Apteker may have facilities and personnel elsewhere, but he has none on the Island and it is unclear how, exactly, he would manage such a single-unit property from afar. And even if such a management plan was in place and supervised by a competent, local company, it will not have much, if any, effect on the publics use of the now-public areas immediately next to Mr. Coreys and Mr. Barneys homes. So far as the record shows, the publics rights and times of access are unrestricted. In such close quarters and, unlike the case with private neighbors whom you come to know, no way of knowing who is there for innocent purposes and who not, the security risks and likelihood of incidents, particularly during the Figawi festivities, are increased. No rational board would conclude that such expansive public access would not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the existing, wholly-private cottage and lot.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Boards decision granting the special permit is reversed and vacated. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

A hotel is defined as a building or buildings on a lot containing a commercial kitchen and rental sleeping units without respective kitchens, primarily the temporary abode of persons who have a permanent residence elsewhere. Id. (emphasis added). The 23 Commercial Wharf cottage will have its own kitchen, and thus is not a hotel.

A lodging, rooming or guest house is defined as a building or buildings on a lot containing rental sleeping units without respective kitchens, and not having a commercial kitchen, primarily the temporary abode of persons who have a permanent residence elsewhere. Id. (emphasis added). The proposed cottage has its own kitchen, and does not have a commercial kitchen. It thus would not appear to fit this definition either.

There was no evidence that the proposed cottage will be used as a time sharing or time interval dwelling unit, defined in the bylaw as:

a dwelling unit or dwelling in which the exclusive right of use, possession or ownership circulates among various owners or lessees thereof in accordance with a fixed or floating time schedule on a periodically recurring basis, whether such use, possession, or occupancy is subject to either: a time-share estate, in which the ownership or leasehold estate in property is devoted to a time-share fee (tenants in common, time-share ownership, interval ownership) and a time- share lease; or time-share use, including any contractual right of exclusive occupancy which does not fall within the definition of time share estate, including, but not limited to, a vacation license, prepaid hotel reservation, club membership, limited partnership or vacation bond, the use being inherently transient.

RICHARD COREY as trustee of TWENTY-ONE COMMERCIAL WHARF NOMINEE TRUST v. BARRY RECTOR, LINDA WILLIAMS, SYLVIA HOWARD, NATHANIEL LOWELL, JOHN McLAUGHLIN and CARL BORCHERT as members of the NANTUCKET PLANNING BOARD, and 23 COMMERCIAL WHARF J.A., LLC.

RICHARD COREY as trustee of TWENTY-ONE COMMERCIAL WHARF NOMINEE TRUST v. BARRY RECTOR, LINDA WILLIAMS, SYLVIA HOWARD, NATHANIEL LOWELL, JOHN McLAUGHLIN and CARL BORCHERT as members of the NANTUCKET PLANNING BOARD, and 23 COMMERCIAL WHARF J.A., LLC.