MATTHEW GOULD, DAVIEN GOULD, PIERRE TILLIER, and GISELLA TILLIER v. FALMOUTH PLANNING BOARD, FALMOUTH HOSPITALITY LLC, and JOHN FAY and ROBERT FAY, as trustees of Fay's Realty Trust.

MATTHEW GOULD, DAVIEN GOULD, PIERRE TILLIER, and GISELLA TILLIER v. FALMOUTH PLANNING BOARD, FALMOUTH HOSPITALITY LLC, and JOHN FAY and ROBERT FAY, as trustees of Fay's Realty Trust.

MISC 14-485074

July 14, 2016

Barnstable, ss.

LONG, J.

DECISION

Introduction

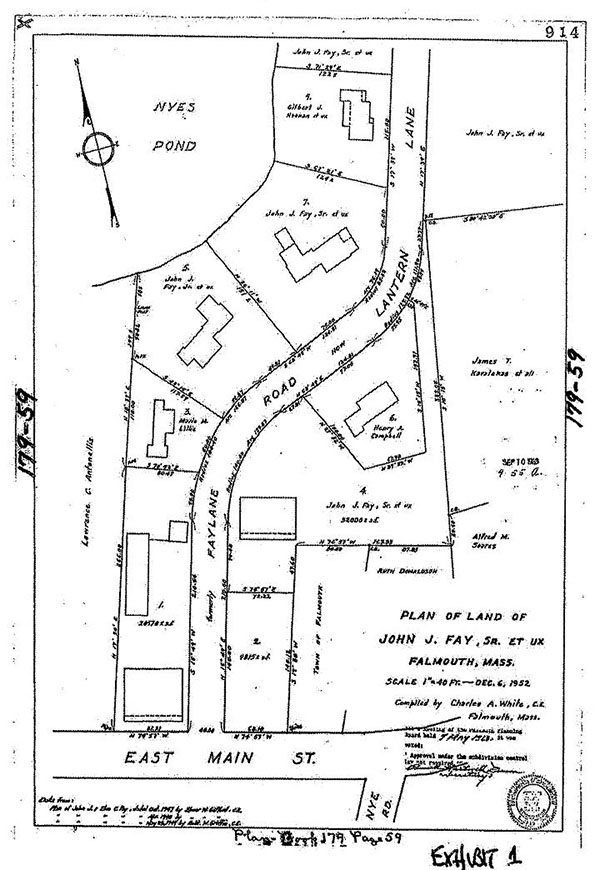

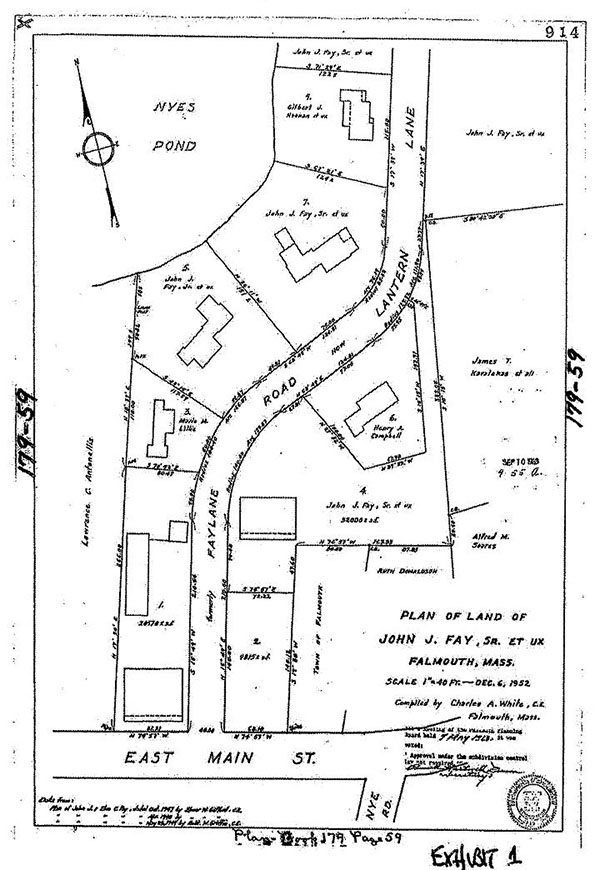

In 1947, the Fay defendants [Note 1] predecessor, John Fay, Sr., created a subdivision near Nyes Pond in Falmouth, with access via Lantern Lane, a private way. The subdivision was subsequently modified in 1952, and the plan of that modification (reflecting the lot configuration as it presently exists) was endorsed by the Falmouth Planning Board. See Ex. 1 (subdivision plan). The Fays still own subdivision lots 1, 2 and 4, as well as the lot marked Town of Falmouth which they acquired from the town in a land swap. Those lots are presently occupied by a series of small commercial buildings, in less than prime condition. The location of those lots, however (on Main Street in Falmouth, near the town center and not far from the ocean), is prime, and the Fays propose to sell them to defendant Falmouth Hospitality LLC for development into a 108-room Marriott Hotel. Such a development, however, requires the combination of the four lots, plus the area between those lots occupied by the Lantern Lane right of way (the Fays own its underlying fee), into one, single lot so that frontage and other zoning requirements can be satisfied. That roadway area cannot be combined into the proposed single lot, however, so long as it is an approved or endorsed subdivision road. It can be combined if it is solely an easement since, under the Falmouth zoning bylaw, easements (unlike subdivision roads) may be included in frontage and lot area calculations even if they are dimensionally and functionally identical to a subdivision road in every material way.

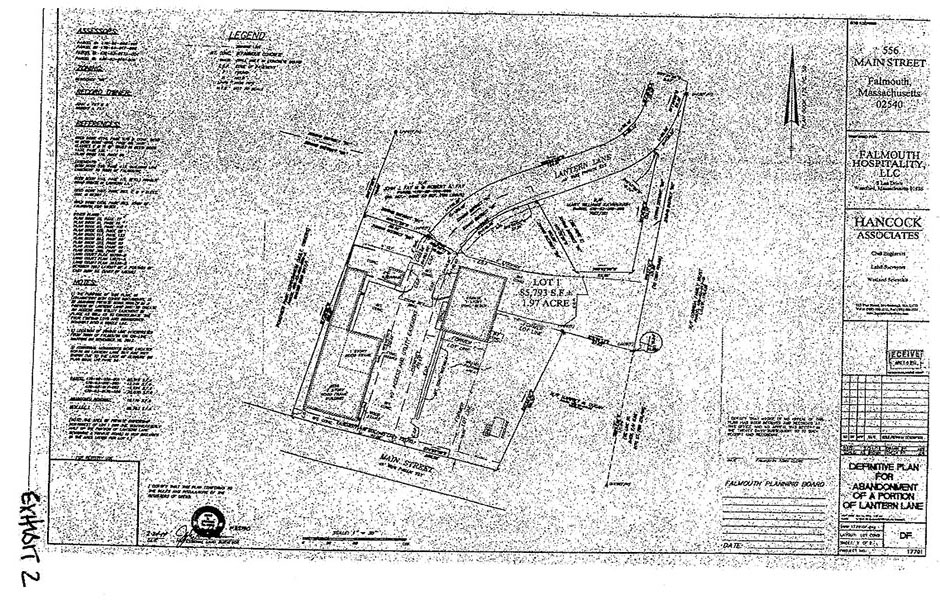

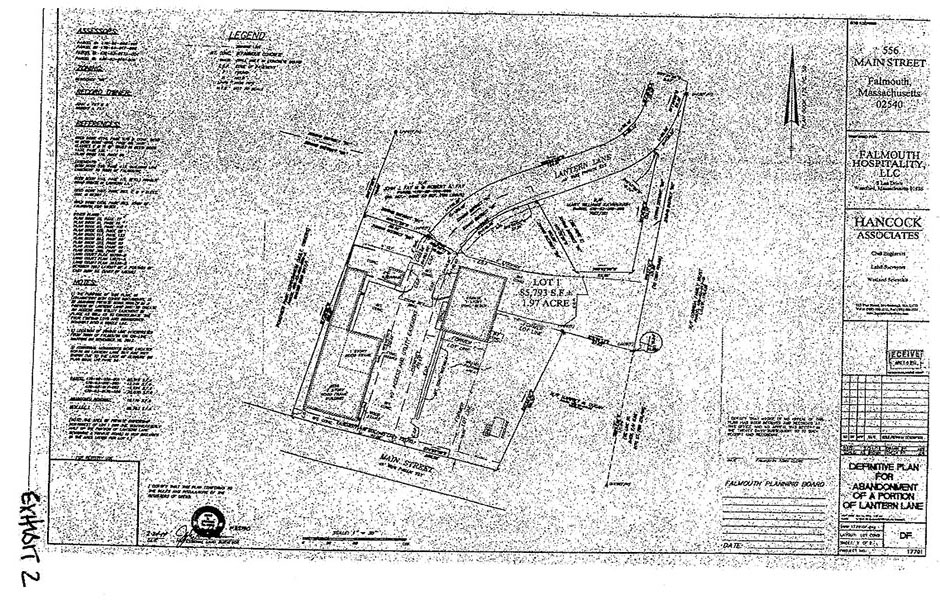

To address that issue, the Fays and Falmouth Hospitality applied to the planning board for permission to abandon that portion of Lantern Lane as a subdivision road and, in its place, substitute an express easement for access and utilities, benefiting all the subdivision lots, in precisely the same location and dimensions. The planning board approved that abandonment, conditioned on the grant of the easement. The plaintiffs, who own homes in the subdivision further down Lantern Lane, timely appealed that approval to this court pursuant to G.L. c. 41, §81BB, seeking its nullification. Their complaint also contains a G.L. c. 231A, §1 request for certain declaratory relief with respect to the proposed easement.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. The plaintiffs can succeed on their G.L. c. 41, §81BB appeal only if the substitution of an express easement for the subdivision road in precisely the same location and dimensions as that road, appurtenant to plaintiffs land, and specifically benefiting and fully enforceable by them affect[s] their lots within the meaning of G.L. c. 41, §81W. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find that there will be no such affect since the roadway will have no physical changes and, with such an express easement, the plaintiffs will have even greater rights assuring their access than they do now. The substitution of an easement for a subdivision road will allow the combination of the defendants lots into one, but that is a matter of zoning and immaterial to G.L. c. 41, §§81K et seq. and subdivision control, which are confined to matters of access and the provision of utility and sanitary services. See Collings v. Planning Bd. of Stow, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 447 , 454 (2011) (A planning board does not have a roving commission. The only purposes recognized by §81M are to provide suitable ways for access furnished with appropriate municipal utilities, and to secure sanitary conditions.) (internal citations and quotations omitted). The planning boards decision is thus AFFIRMED. The plaintiffs request for a declaration that, if the easement substitution is approved and the easement put in place, the proposed Marriott Hotel would overburden their easement rights, is dismissed as premature.

Whether such a hotel can be built and, if so, to what extent and with what conditions, is currently the subject of other proceedings, [Note 2] and thus its effect on the easement, if any, is unknowable at this time.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

Plaintiffs Matthew and Davien Gould live at 5 Lantern Lane in Falmouth, and plaintiffs Pierre and Gisella Tillier at 7 Lantern Lane. [Note 3] Both of their properties are part of the same subdivision as the Fay defendants lots, and are accessed by Lantern Lane, a private way shown as a subdivision road on the subdivision plan. See Ex. 1. All use Lantern Lane for access and utilities. [Note 4]

Lantern Lane begins at Main Street (State Highway Route 28) described by Mr. Gould as a major thoroughfare for the town with shops and restaurants and businesses and lots of human activity and a very vibrant, lively downtown area and proceeds north towards Nyes Pond. See Ex. 1. The lots along Main Street, including the Fay defendants, are in the Business Redevelopment (BR) district. The purpose of that district is:

to promote the revitalization of commercial centers using mixed-use redevelopment integrating retail, office, restaurant and community service uses with housing, such as second floor apartments, condominiums and townhomes. This redevelopment fosters pedestrian-friendly streetscapes by requiring rear and side yard parking, allowing shared parking between businesses and uses, reducing and consolidating curb cuts, and allowing parking reductions in exchange for on- site green space. The district also relaxes front, side and rear yard setbacks to encourage sidewalk development and pedestrian-friendly storefronts to offer streetside gathering places in front of redeveloped properties, rather than front yard parking fields.

Falmouth Zoning Code, Art. XLVI, § 240-240(A). A variety of mixed residential/commercial developments, community service uses (e.g., schools and museums), and purely commercial uses (including hotels) are permitted in this district. See id. at §§ 240-240(B - E). [Note 5]

The Fay defendants own four lots either on or near Lantern Lane, just to the south of the plaintiffs lots. As noted above, the defendants lots are labeled 1, 2, 4 and Town of Falmouth on the subdivision plan. [Note 6] Ex. 1. The defendants seek to (1) combine these four lots (presently used for commercial purposes) into one, single lot, (2) demolish the existing structures, and then (3) construct a Marriott Hotel on the site. To do this requires (1) including the portion of Lantern Lane between the lots in the combined, single lot the Fays own the underlying fee in this portion (and perhaps all) of Lantern Lane, and have the right to make that conveyance [Note 7] (2) abandoning this portion of Lantern Lane as a subdivision road and making it an express easement for the benefit of the subdivision properties, in the same location and dimensions as the subdivision road, [Note 8] and (3) obtaining the planning boards approval for the modification of the subdivision plan to show such abandonment and the substitution of an express easement in that section. Lantern Lane is a private way now, and would continue to be a private way after that change. No buildings or other structures would be placed anywhere in the way, and nothing either on the ground or in practical effect would change in any respect. As

previously noted, this portion of Lantern Lane is proposed to become an easement because, unlike roads formally designated as subdivision roads on subdivision plans, easements do not affect frontage and lot area calculations for zoning purposes in Falmouth.

In the area where Falmouth Hospitality seeks to convert Lantern Lane from a subdivision road to an express access and utilities easement, the roadway of Lantern Lane opens up into a broad paved area on the Fays land that, from all appearances, appears to be a parking lot. There are striped parking spaces on both sides of the through-traffic lane of Lantern Lane, which are located partially within the layout of Lantern Lane on both sides. These parking spaces are regularly used by patrons and employees of the commercial operations located on the Fays lots. [Note 9] The roadway itself is currently in severe disrepair, with numerous potholes, unpaved gravel areas, cracking and crumbling paving materials, debris in the roadway, and overgrown foliage. [Note 10] At the location where the roadway approaches the residential properties, there are outward- facing signs stating Not A Thru Way, Private Way, and Absolutely No Trespassing, originally installed by members of the Fay family around the time the subdivision was created. [Note 11]

On April 10, 2014, Hancock Associates, acting as Falmouth Hospitalitys agent, filed an application with the planning board for approval of a definitive plan providing for an approximately 210 foot section of Lantern Lane running north from Main Street towards the plaintiffs properties, to be abandoned and replaced by an express, deeded, private access and utilities easement intended to replicate subdivision owners present rights in Lantern Lane. [Note 12] The plans stated purpose was to abandon private road rights in a portion of Lantern Lane and to create an access and utility easement in place as well as to consolidate the four existing [Fay] lots and [the area of the] abandon[ed Lantern Lane] roadway into a single lot. Trial Ex. 8. Thus, the four Fay lots, together with the area of Lantern Lane at issue (10,179 square feet) would be consolidated to create a new lot (denoted as lot 1, 85,893 square feet in area, on the attached

Ex. 2), which would contain a forty foot wide access and utilities easement in the precise location of [Lantern Lanes present layout], Agreed Facts (No. 30) (emphasis added), with an equal area (10,179 square feet) as the abandoned section of Lantern Lane. See Agreed Facts (No. 23).

A first public hearing on Falmouth Hospitalitys proposal was held on May 13, 2014. The plaintiffs were notified of, and appeared at, the hearing. [Note 13] Following that hearing, the plaintiffs, through counsel, filed a written objection to Falmouth Hospitalitys proposal with the board. After reviewing the plaintiffs objections to the proposal, Falmouth town counsel, Frank K. Duffy, Esq., and the Falmouth building commissioner, Eladio Gore, both recommended to the Falmouth town planner, Brian Currie, that, notwithstanding the plaintiffs objections, the proposal was within the boards authority to approve as a plan modification pursuant to G.L. c. 41, §81W. Town counsel further recommended that such approval be conditioned upon a written easement for access and utility purposes in form for recording . . . and [a] require[ment] that the access easement be properly maintained and periodically improved so it will adequately serve its intended purpose. Trial Ex. 10. A continued hearing was held on June 3, 2014 (the plaintiffs again appeared), after which the board took the matter under advisement.

At its July 8, 2014 meeting, the planning board voted to approve Falmouth Hospitalitys proposal, subject to the condition that had been recommended by town counsel, namely:

Prior to plan endorsement, the applicant shall submit a written easement for access and utility purposes to the Planning Board for approval in form for recording at the Barnstable County Registry of Deeds. Furthermore, the applicant shall submit details of how the easement shall be maintained and improved to insure that access to Main Street is not impaired.

Trial Ex. 12. [Note 14] Accordingly, the defendants prepared a draft of a proposed easement, granting to those residents of Lantern Lane f/k/a Fay Lane and Morse Pond Road . . . who currently have the right to pass and repass over Lantern Lane f/k/a Fay Lane, their successors or assigns: [Note 15]

A permanent non exclusive easement of way for all purposes for which streets or ways are commonly used in Falmouth, Massachusetts, to be used appurtenant to the respective lot or parcel of land, over that certain area of land situated in Falmouth, County of Barnstable, Massachusetts, containing approximately 10,179 s.f., and more particularly described as Proposed Access and Utility Easement shown on a plan . . . [to be prepared and recorded].

Trial Ex. 14. The easement further provided that the Fays reserved the right to maintain and improve the easement area so long as it did not materially interfere with the grantees rights. [Note 16]

The boards approval of Falmouth Hospitalitys proposal was filed with the Falmouth town clerk on July 9, 2014, and the plaintiffs timely appealed that approval to this court, coupling it with the request for declaratory relief previously noted.

Whether the proposed Marriott Hotel will be built and, if so, in what size, with what parking requirements and configuration, and with what traffic impacts is presently unknown. The Cape Cod Commission has denied permission for the hotel development as presently proposed (a denial currently on appeal to this court, see Falmouth Hospitality LLC v. Cape Cod Commission, Land Court Case No. 15 MISC. 000414 (KCL)), and the zoning board of appeals has not yet addressed the merits of the necessary special permit.

Additional facts are discussed in the Analysis section below.

Analysis [Note 17]

The plaintiffs primary claim [Note 18] is their G.L. c. 41, § 81BB [Note 19] appeal of the boards approval of Falmouth Hospitalitys abandonment plan. The standard of review in G.L. c. 41, § 81BB appeals is de novo. [Note 20] Mac-Rich Realty Const., Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Southborough, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 79 , 81 (1976); see also Strand v. Planning Bd. of Sudbury, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 935 , 936 (1979) (appellant has the burden to prove that the board exceeded its authority and acted improperly); Selectmen of Ayer v. Planning Bd. of Ayer, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 545 , 548 (1975).

Specifically at issue in this case is whether the board properly exercised its power to modify an approved subdivision plan pursuant to G.L. c. 41, § 81W. Under that section:

A planning board. . . shall have power to modify, amend or rescind its approval of a plan of a subdivision, or to require a change in a plan as a condition of its retaining the status of an approved plan. All of the provisions of the subdivision control law relating to the submission and approval of a plan of a subdivision shall, so far as apt, be applicable to the approval of the modification, amendment or rescission of such approval and to a plan which has been changed under this section.

No modification, amendment or rescission of the approval of a plan of a subdivision or changes in such plan shall affect the lots in such subdivision which have been sold or mortgaged in good faith and for a valuable consideration subsequent to the approval of the plan, or any rights appurtenant thereto, without the consent of the owner of such lots, and of the holder of the mortgage or mortgages, if any, thereon . . . .

G.L. c. 41, §81W. [Note 21] Since the plaintiffs have not consented to the requested modification (the abandonment of this portion of the road as a subdivision road [Note 22] and its replacement in this section with an express easement), the test thus becomes whether the modification will affect the plaintiffs lots within the scope and meaning of the subdivision control law, G.L. c.41, §§81K, et. seq. [Note 23] Guidance on this test is given in Patelle v. Planning Bd. of Woburn, 20 Mass. App. Ct. 279 , 283-284 (1985).

As explained in Patelle, local planning boards are:

authorized by the Subdivision Control Law to protect the safety, convenience and welfare of a municipality's inhabitants by regulating the laying out and construction of ways in subdivisions. The law is designed to benefit those inhabitants primarily and those who purchase lots in developments only secondarily. As part of their powers, planning boards coordinat[e] the ways in a subdivision with each other and with the public ways in the city or town in which it is located and with the ways in neighboring subdivisions. An expansive construction of the word affect in [G.L. c. 41,] § 81W would unduly restrict this power. Effectively, a planning board would be unable to authorize, and a developer would be unable to execute, development of property in stages, . . . by connecting one stage to the next through the extension of roads and transformation of open land to lots.

To be sure, the Subdivision Control Law establishes an orderly procedure for definitive action within stated times . . . so that all concerned may rely upon recorded action [emphasis in original] . . . . That principle does not, however, extend to inflexible retention of aspects of a recorded subdivision plan that do not have a direct and tangible impact, as described in this opinion, on the property rights of lot purchasers. If purchasers of lots in a subdivision desire such protection, they may obtain it by insisting on specific covenants in their deeds.

Patelle, 20 Mass. App. Ct at 283-284 (emphasis added; internal citations and quotations omitted).

The defendants argue that Patelle is directly on point factually with, and determinative of, this case. The plaintiffs disagree, but they do not succeed in meaningfully distinguishing the facts in Patelle from those at issue here. [Note 24] In Patelle, a planning board approved a modification of a subdivision plan to relocate empty space in the subdivision, to add several additional lots in areas previously designated for open space, and (most relevant for present purposes) to convert a cul-de-sac into a through-street. The Patelle plaintiffs contended that doing so would result in diminished property values, replacing the cul-de-sac would result in additional traffic, and adding additional house lots would result in a less agreeable living situation due to decreased open space.

The Appeals Court disagreed, holding that the word affect, as it appears in G.L. c. 41, § 81W, does not have the broad meaning the plaintiffs ascribe to it, id. at 281, because the stated purpose of the notice requirement is to avoid the possibility of upsetting land titles. Id. (internal quotation omitted). Thus, the Patelle court held:

the plan modifications which the Legislature sought to guard against when it used the verb affect were those which impaired the marketability of titles acquired by bona fide purchasers from subdividers. Examples would be modifications which altered the shape or area of lots, denied access, [Note 25] impeded drainage, imposed easements, or encumbered the manner and extent of use of which the lot was capable when sold. The target of the statute was not those changes which might have an indirect qualitative impact, such as alteration of a dead end street into a through street.

Id. at 282. Based on this analysis, the Appeals Court determined that the amendments at issue in

Patelle did not rise to the level of an affect, reasoning as follows:

Any number of physical changes affect, in greater or lesser degree, lots in a subdivision, e.g., location of trees, width of streets, planting between the curb and lot lines, traffic signals, overhead or underground utilities, or street lighting. They do not, however, limit the utility of those lots and, hence, do not affect them in the statutory sense. The alterations approved by the planning board in the instant case fall into this indirect impact category. They affect traffic pattern, view, and over-all neighborhood density, matters as to which the plaintiffs had acquired no rights through covenants, easements, or other tool of private land use control. The plaintiffs' complaints about traffic or an unwanted backyard neighbor are matters with which § 81W is unconcerned.

Id. at 282-283. [Note 26]

Here, the plaintiffs have not demonstrated any concrete effect that the proposed change would have on the rights protected by G.L. c.41, §81W. To the contrary, the parties stipulated to a number of facts indicating that changing Lantern Lane from a subdivision road into a deeded access and utilities easement would have no substantive effect on the plaintiffs at all. They agreed that it would not impact the shape or area of [the] plaintiffs land, affect drainage on Lantern Lane, or impose an easement on [the] plaintiffs land. Agreed Facts (No. 29). They agreed that [t]he proposed easement is to be located in the precise location of the existing forty [foot] (40) wide private way lay out known as Lantern Lane. Agreed Facts (No. 30). And they agreed that Falmouth Hospitality submitted proposed easement language to the board for approval in accordance with the boards July 8, 2014 directives for the express purpose of ensuring that the plaintiffs rights would not be abridged. [Note 27] Agreed Facts (No. 31). [Note 28]

In sum, there was no evidence and certainly no persuasive evidence that the proposed change would impact the plaintiffs in any meaningful way in their use of Lantern Lane for the benefit of their properties. Indeed, the express easement will provide the subdivision residents with even more rights than they currently possess, since they will each now have an individual, private right to enforce those easement rights to their full extent. Moreover, they do not even allege (much less prove) that changing Lantern Lane from a subdivision road to an easement would adversely affect the marketability of their titles. See Patelle, 20 Mass. App. Ct. at 282.

Having shown no actual affect on their rights (access, title, or otherwise), the plaintiffs fall back on a contention that the proposed change in and of itself, and irrespective of what impact the change would have -- would per se affect their rights within the meaning of G.L. c. 41, § 81W. As the Appeals Court has recently shown, there is no merit to this argument. A private subdivision way is simply an easement. See 150 Main Street LLC v. Martino, Appeals Ct. Case No. 15-P-315, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28 at 4-6 (Feb. 18, 2016)). As held in that case:

Substantively speaking, on the facts presented here, the terms [way and easement] are interchangeable . . . . An easement is a right whereby one person has use of the land of another for a definite purpose, such as ingress and egress. . . . Here, a private way is a way over which someone holds an easement for passage. The distinction is without a difference; easement and way are simply names or labels for the same interest. Thus, regardless of the term employed . . . [ones] right of passage . . . remains unchanged and certain.

Id. See also Barlow v. Chongris & Sons, Inc., 38 Mass. App. Ct. 297 , 299 (1995), in which the court noted:

The words private way include defined ways for travel, not laid out by public authority or dedicated to public use, that are wholly the subject of private ownership, either by reason of the ownership of the land upon which they are laid out by the owner thereof or by reason of ownership of easements of way over land of another person . . . .

In sum, in terms of the rights they create and the practical effect of those rights, the existing subdivision road in this section (a private way) and the proposed private easement to replace it (a private way), are the same. The fact that the planning board may have a role in the one, while the other is privately enforceable to its full extent is, as the Martino court observed, a distinction

without a difference because, whether this 210 foot portion of Lantern Lane is classified as a private subdivision road or as a private access and utilities easement, the plaintiffs rights [Note 29] remain unchanged and certain.

Critically, this is not disputed by the defendants. Rather, they openly concede that they cannot defeat the plaintiffs rights to use Lantern Lane. That is because private easement rights cannot be unilaterally changed to the detriment of the easement holder. Cf. M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 89-94 (2004). Thus, irrespective of what the board does in terms of its town planning and subdivision control, the plaintiffs rights in Lantern Lane are what they are. The planning board may have approved, on paper, that Lantern Lane, as a subdivision road, now ends 210 feet short of Main Street. But that does not affect the plaintiffs rights to continue to pass over its entire length and run their utilities through it.

Despite the clear guidance of M.P.M. Builders and its progeny, the plaintiffs persisted, without any reasonable explanation, in their argument that their rights in Lantern Lane might enjoy fewer protections if classified as private easement rights rather than as rights in a subdivision road. The plaintiffs fear, apparently, is that the Fays might, at some point in the future, try to restrict or limit their use of Lantern Lane, and that there would, in that case, be no [ ] review by a town entity to approve, disapprove, supervise, [or] guard my rights. [Note 30] No reliable evidence was produced, however, to suggest that the Fays would have any right -- let alone any reason or inclination -- to do so, nor to suggest that the plaintiffs would be without recourse to enforce their private property rights. Thus, their argument is not only entirely speculative, it is not supported by the law regarding the protection of private property rights.

In fact, Patelle and M.P.M. Builders indicate the opposite: showing that the plaintiffs would actually enjoy more rights with an express easement with greater and more direct protections, not subject to modification by the board than they now have with a subdivision road. Tellingly, as the Appeals Court noted in Patelle, if subdivision lot purchasers were to desire inflexible retention of aspects of a recorded subdivision plan that do not have a direct and tangible impact . . . on the property rights of lot purchasers . . . , they may obtain it by insisting on specific covenants in their deeds. Patelle, 20 Mass. App. Ct. at 284.

Such protection is precisely what the defendants are offering to the plaintiffs express, deeded easement rights pursuant to a private agreement that are not readily subject to change, review, or rescission by any subdivision control, planning, zoning, or other municipal authority. The plaintiffs would have private property rights enforceable in any court with jurisdiction over such disputes.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the Falmouth Planning Board allowing the abandonment of the 210-foot southerly portion of Lantern Lane as a subdivision road, conditioned on its conversion into an express private easement in the same location and dimensions, is AFFIRMED and the plaintiffs appeal from that decision is DISMISSED, in its entirety, with prejudice, with the matter remanded to the board for review and approval of the form of easement. The plaintiffs declaratory judgment claims relating to the potential overburdening or overloading of the easement are DISMISSED as premature.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] John Fay and Robert Fay, as trustees of Fays Realty Trust.

[Note 2] These include a separate case in this court involving Falmouth Hospitalitys appeal from the Cape Cod Commissions denial of permission to build the Marriott. See Falmouth Hospitality LLC v. Cape Cod Commission, Land Court Case No. 15 MISC. 000414 (KCL).

[Note 3] The Goulds and Tilliers properties are lots 5 and 7, respectively, on the 1952 subdivision plan. See Ex. 1. As previously noted, the Fays lots are numbers 1, 2, and 4 and the one labeled Town of Falmouth.

[Note 4] The Goulds deed explicitly sets out the Goulds easement rights in Lantern Lane, as follows: [t]here is conveyed as appurtenant to the [ ] premises the right to use the way known as Fay Lane Road [n/k/a Lantern Lane] as shown on plan hereinbefore mentioned, for all purposes for which ways may be commonly used, such use to be in common with others now or hereafter to be entitled to similar rights, and specifically reserves to John J. Fay, Sr. and Elva C. Fay, their heirs and assigns, the right to grant similar easements to others in said way. Trial Ex. 5.

Neither the Tilliers deed, nor any prior deeds in their chain of title going back to the Fay family, contain any such specific language. See Trial Ex. 6. Nonetheless, the defendants do not dispute that the Tilliers have a right to use Lantern Lane. See Agreed Facts (No. 12).

[Note 5] Hotels (i.e., commercial accommodations) are expressly permitted in the BR district, but require a special permit from the Falmouth Board of Appeals. See id. at § 240-240(G)(1)(a).

[Note 6] Lots 1, 2, and 4 are part of the same subdivision in which the plaintiffs lots are located, and thus have the same rights to use Lantern Lane as all the other subdivision lots. The Town of Falmouth lot was never part of the subdivision, but was acquired by the Fays in the 1960s in a land swap with the Town of Falmouth.

[Note 7] The plaintiffs do not dispute the Fay defendants fee ownership of this portion of Lantern Lane and, so far as the record shows, the Fays retained ownership to the fee in the remainder of Lantern Lane as well. See n. 4, supra (noting that the Gould deed, which granted that property an express easement to use Lantern Lane, specifically reserves to John J. Fay, Sr. and Elva C. Fay, their heirs and assigns, the right to grant similar easements to others in said way.

[Note 8] Compare Ex. 1 (subdivision plan) with Ex. 2 (abandonment plan, showing the proposed easement in the same location and with the same 40 width). The present actual roadway surface varies from twenty to twenty-four feet in width. It narrows significantly as Lantern Lane approaches the residential lots, where grassed buffer strips begin to line both sides of the surface.

[Note 9] To the left of this area of Lantern Lane are a commercial store (currently, a consignment shop), several garages, a loading dock, and an open storage field. To the right is an open parking lot used primarily for storing commercial vehicles and building materials, a spring water filling facility, and a large warehouse with several loading docks. Mr. Fay testified that his family used these properties for various family businesses (including a propane company, an appliance company, and a plumbing supply company) from approximately the 1940s until the 1990s. Since then, the Fays have leased the properties to various commercial operations, including a sheetrock installer, a painting business, a landscaper, and a plumbing and kitchen supply business.

[Note 10] The town does not maintain Lantern Lane in any way, other than the plowing of snow. The Fays maintained and repaired it, at their own expense, as needed for their commercial operations, until the 1990s, after which they stopped doing so. The only recent maintenance of the road appears to be a re-striping of the parking spaces in 2013, as ordered by the town.

[Note 11] As evidenced by the photos in the record, it is not readily apparent to passers-by on Main Street that Lantern Lane continues past the Fays commercial properties. As noted, the area, with its striped parking areas, appears to be a dilapidated parking lot. Only upon closer inspection does it become apparent that Lantern Lane continues past the parking lot area into the residential part of the subdivision. This, in addition to the signage suggesting no outlet, strongly discourages traffic from all but those traveling to the subdivision properties. It is thus unsurprising that multiple witnesses described the traffic on Lantern Lane as minimal.

[Note 12] The plaintiffs initially raised an issue as to Falmouth Hospitalitys standing to have filed that application. The parties now agree that Falmouth Hospitalitys lease agreement with the Fays included an authorization to do so. See Agreed Facts (No. 18).

[Note 13] Notice to the plaintiffs was required pursuant to G.L. c. 41, § 81T.

[Note 14] At this hearing, the board noted that, in addition to the recommendations of approval from town counsel and the building inspector, the Falmouth Fire and Rescue Department also had reviewed and approved the proposal.

[Note 15] Attorney Robert Moriarty proposed that the broad, attributive language identifying the grantees of this easement be replaced by a schedule specifically identifying those grantees.

[Note 16] Mr. Moriartys revised easement (Trial Ex. 38) would not merely grant the Fays a right to maintain and upkeep the easement, but affirmatively would require that they do so. He further recommended eliminating the limited indemnity set forth in the original proposed easement. See Trial Ex. 38.

[Note 17] As a threshold matter, I note that the defendants have challenged the plaintiffs standing, arguing that the plaintiffs are not aggrieved because none of their property rights would be affected, in the statutory sense, by the proposed abandonment plan. See Krafchuk v. Planning Bd. of Ipswich, 453 Mass. 517 , 522 (2009); Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 33 (2006). The plaintiffs argue in response that the mere fact that a subdivision road is to be replaced with an easement without their consent amounts to an effect and an injury, and thus confers standing.

As these arguments demonstrate, the question of whether the plaintiffs are aggrieved for standing purposes is effectively the same question as whether the proposed change would affect the plaintiffs rights under G.L. c. 41, §81W -- the substantive question presently before me. I thus need not, and do not, reach the standing question because, as discussed below, I find and rule that the plaintiffs claims fail on their merits.

[Note 18] As noted, the plaintiffs also seek related declaratory relief under G.L. c. 231A.

[Note 19] Any person, whether or not previously a party to the proceedings, or any municipal officer or board, aggrieved by . . . any decision of a planning board concerning a plan of a subdivision of land . . . may appeal to the superior court for the county in which said land is situated or to the land court . . . . The court shall hear all pertinent evidence and determine the facts, and upon the facts so determined, shall annul such decision if found to exceed the authority of such board, or make such other decree as justice and equity may require. The foregoing remedy shall be exclusive, but the parties shall have all rights of appeal and exceptions as in other equity cases. G.L. c. 41, § 81BB.

[Note 20] As in G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeals, de novo means that the court conducts a hearing de novo, finds facts based solely on the evidence in that proceeding, and then determines the validity of the planning boards decision in light of those facts. See Mac-Rich Realty Const., Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Southborough, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 79 , 81 (1976).

[Note 21] The plaintiffs argue that this section cannot authorize the modification of a subdivision plan approved prior to the codification of the modern Subdivision Control Law at G.L. c. 41, §§ 81K - 81GG. But if that were the case, it would mean that local planning boards would be unable to modify or discontinue subdivisions approved prior to 1953, which is clearly contrary to both the language and spirit of the law. See G.L. c. 41, § 81GG. I find this argument meritless.

[Note 22] The rest of the Lantern Lane subdivision road remains a subdivision road.

[Note 23] The relevant affects must be those addressed by the subdivision control law, whose purpose is to protect the health and welfare of the community by regulating the laying out and construction of ways in subdivisions providing access to the several lots therein, but which have not become public ways, and ensuring sanitary conditions in subdivisions and in proper cases parks and open areas (G.L. c. 41, §81M) in brief, to ensure sufficient access to the lots within the subdivision and to provide them with municipal services. Dolan v. Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 359 Mass. 699 , 701 (1971), citing G.L. c. 41, §81M (internal emphasis and quotations omitted). The planning board may also review a subdivisions compliance with the use and lot-dimension restrictions in the local zoning ordinance or bylaw, see Beale v. Planning Bd. of Rockland, 423 Mass. 690 (1996), but nothing else. A planning board does not have a roving commission. The only purposes recognized by §81M are to provide suitable ways for access furnished with appropriate municipal utilities, and to secure sanitary conditions. Collings v. Planning Bd. of Stow, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 447 , 454 (2011) (internal citations and quotations omitted). Thus, the fact that the replacement of the subdivision road with an express easement will, for zoning purposes, allow the defendants to include the easement area in the combined lot is irrelevant to the issues in this case. All that is relevant, for affect purposes, is access and utilities.

[Note 24] They also fail to demonstrate that the board lacked good reason to approve the defendants proposal, arguing only that the approval amounts to a de facto variance. The defendants convincingly rebut this claim, noting that the boards action advanced the stated goals of the BR zoning district, cited above.

[Note 25] I take it to be an open question how much of a restriction upon access a subdivision modification could effect before access would be deemed denied under this Patelle standard. However, because the plaintiffs offer no evidence that their access would be meaningfully affected at all, I need not and do not decide this question here. C.f. Matthews v. Planning Bd. of Brewster, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 456 , 464 n. 9 (2008) (finding, in dicta, that changing a subdivision road would have required owners consent where a restrictive covenant specifically forbade the change).

[Note 26] The Appeals Court further distinguished Stoner v. Planning Bd. of Agawam, 358 Mass. 709 , 714-715 (1971) and Bigham v. Planning Bd. of No. Reading, 362 Mass. 860 (1972), as each of those cases involved the rescindment of a subdivision plan, which rendered subdivision lots already sold useless for building purposes. Patelle, 20 Mass. App. Ct. at 283; see also Terrill v. Planning Bd. of Upton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 171 , 175 n. 9 (2008) (noting the same distinction). Nothing like that occurred here.

[Note 27] At each juncture in this dispute, the defendants have emphasized that they have no intention of substantively changing the plaintiffs rights in any way, and are willing to do whatever is necessary in drafting the easement language to accommodate those rights and to ensure they are not impinged upon. To that end, the defendants have retained a conveyancing expert to prepare an easement protecting subdivision owners rights in Lantern Lane and to ascertain who actually has such rights needing protection. For its part, the board has likewise recognized the plaintiffs rights, sought to protect them (by implementing town counsels recommendation that approval be conditioned upon the grant of a written easement for access and utility purposes in form for recording . . . and [a] require[ment] that the access easement be properly maintained and periodically improved so it will adequately serve its intended purpose, Trial Ex. 10), and conditioned final approval of the proposed change in Lantern Lane upon its approval of such an easement.

[Note 28] Mr. Gould speculated that the Fays property, once developed, might generate additional traffic, but the issue in this case is not what effect future development might have, but rather only what effect the abandonment of Lantern Lane might have. In any event, Mr. Gould lacked expertise to testify as to traffic impacts, and the plaintiffs did not seek to introduce any expert evidence on that subject.

This case, it would seem, will serve as a prelude to a subsequent challenge by the plaintiffs to the defendants development of the Fays property. If that is the case, they will have ample opportunity to raise traffic concerns then. For present purposes, they are simply not relevant. See Patelle, 20 Mass. App. Ct. at 283 ([C]omplaints about traffic . . . are matters with which § 81W is unconcerned.).

[Note 29] As noted above, the Goulds deed to their property includes an express, deeded easement to use Lantern Lane. The Tilliers deed does not contain an express easement to use Lantern Lane, but the defendants do not dispute that they do have a right to use it; presumably, that right would take the form of an implied access easement or an easement by estoppel. See generally Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 344-349 (1967) (discussing circumstances under which implied access easement rights arise). In addition, documents recorded with the local registry show that the Fays, in addition to granting express easements to most of the subdivision lot owners (the Tilliers lot being an exception), also granted several express easements in Lantern Lane to the town (for running municipal water lines) and to then-existing utilities providers (to whose rights present providers presumably have succeeded).

[Note 30] Mr. Gould readily admitted that he lacks legal training, but, even so, his assumption as to the extent of municipal protections of his rights in subdivision ways appears to be mistaken. See testimony of town planner Brian Curry at Trial Tr. pp. 30-32 (for subdivision control purposes, the Planning Board never concerns itself about who has [easement] rights in subdivision ways) and building commissioner Eladio Gore at Trial Tr. 93-96 (subdivision owners substantive rights in Lantern Lane were not relevant to the determination of whether the proposed change would be proper under zoning regulations).

MATTHEW GOULD, DAVIEN GOULD, PIERRE TILLIER, and GISELLA TILLIER v. FALMOUTH PLANNING BOARD, FALMOUTH HOSPITALITY LLC, and JOHN FAY and ROBERT FAY, as trustees of Fay's Realty Trust.

MATTHEW GOULD, DAVIEN GOULD, PIERRE TILLIER, and GISELLA TILLIER v. FALMOUTH PLANNING BOARD, FALMOUTH HOSPITALITY LLC, and JOHN FAY and ROBERT FAY, as trustees of Fay's Realty Trust.