Introduction

In this action, plaintiff Concetta DiNino, as trustee of the Concetta DiNino Irrevocable Trust, contends that she has a prescriptive easement, appurtenant to her property at 6 Victoria Terrace in Dedham, to drive over and park upon a section of her neighbor Adrian Newman's driveway, and to continue driving beyond the present driveway area, over a now-fenced off further section of Mr. Newman's land, to a place in her back yard where she and her family members parked in the past and would like to park again. Although Ms. DiNino's use of Mr. Newman's property (No. 2-4 Victoria Terrace, which Ms. DiNino and her late husband previously owned, then deeded to their daughter and son-in-law, and which the daughter and son-in-law recently sold to Mr. Newman) is not necessary for these purposes (removing an existing raised flower bed along the side of her house would give her sufficient space on her own land for parking

and vehicular access to her back yard), [Note 1] using the disputed area avoids the need for that removal, and she and her family members used it for many, many years when its ownership was in the DiNino family.

The mere fact of use, however no matter how long that use took place is insufficient to establish a prescriptive easement. For such an easement to accrue, the use must have been adverse. See Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 263 (1964) (prescriptive easement requires "uninterrupted, open, notorious and adverse use for twenty years over the land of the defendant"). Whether the DiNinos' past use of the area in dispute was adverse or permissive is thus the central issue in the case. See id. ("permissive use is inconsistent with adverse use").

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule that No. 6's past use of the disputed area was permissive, not adverse, and thus that no prescriptive easement exists. The plaintiff's claims are thus DISMISSED, WITH PREJUDICE.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

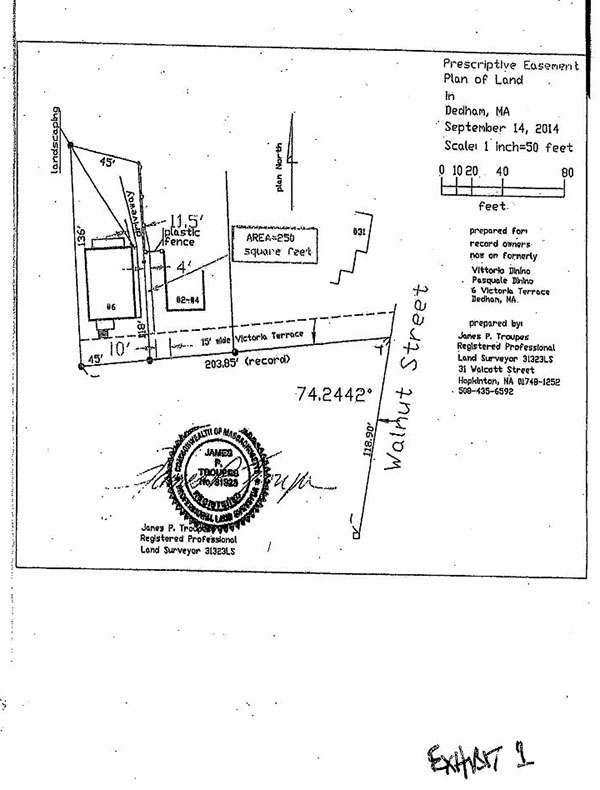

Ms. DiNino's house at 6 Victoria Terrace (a two-family), and Mr. Newman's house at 2-4 Victoria Terrace (also a two-family), are side-by-side neighbors. As seen from the street, No. 6 is on the left and No. 2-4 is on the right. The area at issue is between the two houses. See Ex. 1. [Note 2]

No. 6 Victoria Terrace (the plaintiff's property)

6 Victoria Terrace has been owned by the DiNino family since August 4, 1959 when Ms. DiNino and her late husband, Vittorio DiNino, purchased and titled it in themselves as tenants by the entirety. Mr. DiNino passed away in 2006 and, on November 10, 2009, Ms. DiNino (now its sole owner) conveyed it to her daughters, Maryann DiNino, Lory Vettori, and Carla Boudreau, as trustees of the MLC Trust. In May 2011, the daughters (as MLC trustees) conveyed it back to Ms. DiNino, who now took title as trustee of the Concetta DiNino Irrevocable Trust. During all this time from 1959 to the present Ms. DiNino and her daughter Maryann lived at No. 6 continuously. Mr. DiNino also lived there before his death, and the other daughters (Lory Vettori and Carla Boudreau) until they married and moved out.

No. 2-4 Victoria Terrace (currently owned by the defendant)

At the time the DiNinos purchased No. 6 in 1959, the house next door, No. 2-4 (now Mr. Newman's), was owned by Arthur Drouin. Mr. Drouin by all accounts, the friendliest of neighbors died many years later and, on November 3, 1981, his estate sold No. 2-4 to Vittorio DiNino (Ms. DiNino's late husband) and Mr. DiNino's brother Pasquale. [Note 3] The house was renovated over the course of the next four years [Note 4] and, after the renovations were complete, Vittorio and Pasquale deeded it to Mr. and Ms. DiNino as tenants by the entirety on August 12, 1986. Mr. and Ms. DiNino thus owned both No. 6 and No. 2-4 as tenants by the entirety on that date (i.e., in common title), and continued to do so until March 22, 1988 when they conveyed No. 2-4 to their daughter, Carla Boudreau, and her husband James, "for consideration of love and affection," keeping No. 6 for themselves. The Boudreaus had been living in No. 2-4 since 1987, and continued to do so (renting its other unit to tenants) until they sold it to Mr. Newman on June 25, 2013. Mr. Newman presently resides in the first floor unit (No. 2) with his wife and young children, and rents the second floor unit (No. 4) to tenants.

The Area in Dispute

As noted above, the dispute in this case is over (1) the DiNinos' use of Mr. Newman's section of the paved-together driveway between the properties, and (2) whether Mr. Newman must remove a portion of the fence he built across his section of the rear of that driveway so that the DiNinos can drive over a corner of his land to park in their back yard. See Ex. 1. Not surprisingly, the dispute did not exist when the two properties were both in the DiNino family. It has only arisen since No. 2-4 left the family and was sold to Mr. Newman. Although over just a modest-sounding 250 square feet, the dispute is important to both parties. Ms. DiNino wants to continue doing what she and her family members did for years (driving over and parking on that land), and to avoid having to remove her raised flower bed to achieve the same result. For his part, Mr. Newman wants the exclusive use of the entirety of his portion of the driveway so that everything he owns of record is available for his and his tenants' parking, and wants his fence at the back of the driveway to remain, including at the corner in dispute, so that the corner area can continue to be a part of the back yard enclosure where his children play.

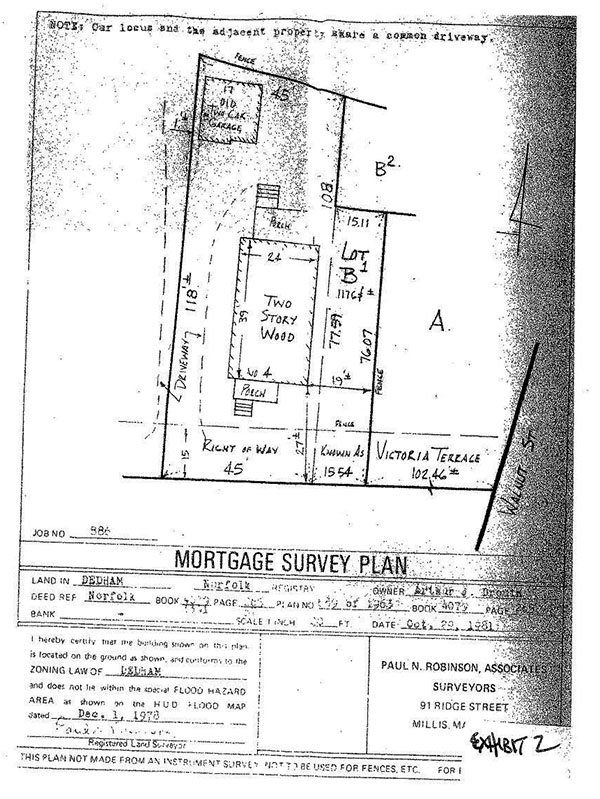

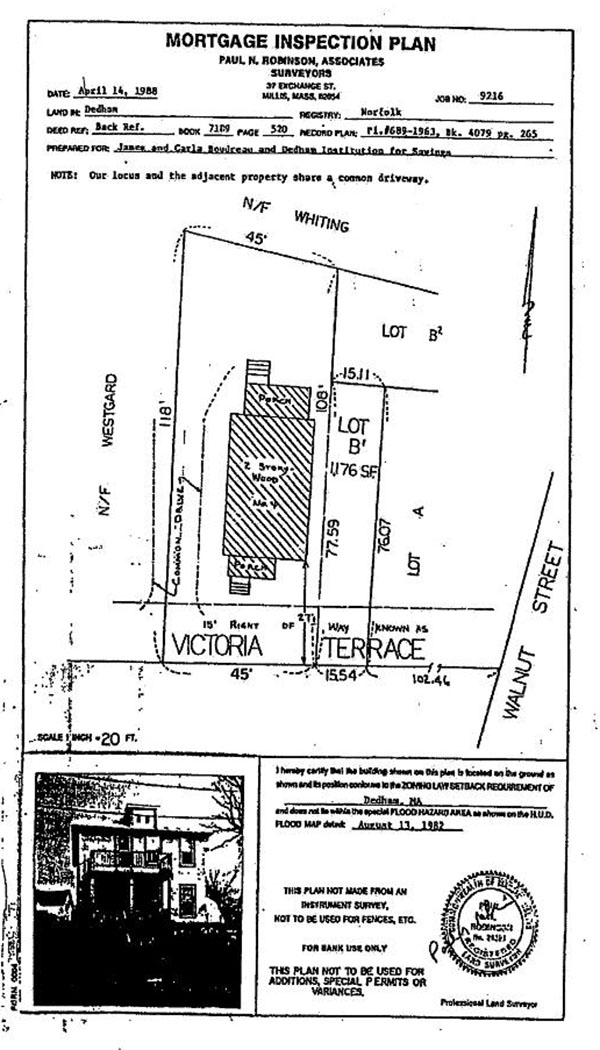

Neither No. 6 nor No. 2-4 have an express easement to use any of the other's land, nor has any such express easement ever existed. At least as early as 1959, however, when Ms. DiNino and her husband purchased No. 6, both No. 6 and No. 2-4 shared a dirt and gravel driveway between the two houses that led from the road in front (Victoria Terrace) to the back of their properties. An October 29, 1981 mortgage survey plan of No. 2-4 (Ex. 2) apparently done in connection with Mr. DiNino and his brother's November 3, 1981 purchase of No. 2-4 from Mr. Drouin's estate [Note 5] shows the driveway primarily on the No. 2-4 lot and ending at No. 2-4's back yard garage, but with its western edge just over the record boundary with No. 6 and a narrow spur leading to an area in No. 6's back yard immediately adjacent to No. 2-4's garage. Photographs from approximately this time show cars parked not only in No. 2-4's back yard, but also in No. 6's back yard, tandem-style, in the area immediately next to No. 2-4's garage, corroborating the driveway's shared use. [Note 6] I need not decide if the shared use was permissive or adverse at this time (although the friendly relations between the DiNinos and Mr. Drouin strongly suggests that it was mutually permissive), because the DiNinos subsequently purchased No. 2-4 and both properties were titled in the names of Vittorio and Concetta DiNino as tenants by the entirety from August 12, 1986 until March 22, 1988. That merger of title eliminated all existing easements (if any), and the subsequent conveyance of title from the DiNinos to their daughter and son-in-law (Carla and James Boudreau) did not revive them. See Williams Bros. v. Peck, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 682 , 684- 685 (2012). [Note 7]

The determinative period of time is thus March 22, 1988 (when the common ownership was severed with the conveyance of No. 2-4 from Mr. and Ms. DiNino to their daughter and son-in-law) to the date this case was filed (Dec. 2, 2014) to see what, if any, prescriptive rights accrued over the No. 2-4 property, appurtenant to No. 6. See Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 , 542 n. 8 (1996) ("In Massachusetts, the filing of a petition to register title to land or a complaint to establish title to land immediately interrupts adverse possession of that land."). A focus on the origins of the post-March 22, 1988 use is also important because a use that begins as permissive is presumed to continue permissive absent proof to the contrary. See Hall v. Stevens, 9 Metcalf (50 Mass.) 418, 422 (1845); Begg v. Ganson, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 217 , 219 (1993).

The Boudreaus (the DiNinos' daughter and son-in-law) acquired No. 2-4 by gift from Mr. and Ms. DiNino "for consideration of love and affection." They had already been living there for over a year, and the outright gift of the property shows the warm feelings between them. Adverse acts, sufficient to establish a prescriptive easement, must be of such a nature that the true (record) owner would see them as a claim of right by the claimant the right to do these things and thus be on notice that he (the record owner) should take countermeasures. See Proprietors of the Kennebeck Purchase v. Springer, 4 Mass. 415 , 418 (1808); Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 848 (2004); Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556 (1993). The activities that occurred in the disputed areas were the opposite of that. They were always cooperative, and cannot be seen (and I do not see them) as claims of right, adverse to the owner.

After the Boudreaus moved in to No. 2-4, both they and the DiNinos in No. 6 (Ms. Boudreau's mother, father, and sister Maryann) jointly maintained the driveway between the houses. Members of both households shoveled snow off it, blew leaves off it, and painted the fences alongside it. Mr. DiNino was retired and thus did much of the work, but everyone pitched-in. None of these activities were done as an assertion of "right" to the others' land, but rather as family members helping each other. The most telling event came in 1990, when Mr. and Ms. DiNino had the driveway paved after obtaining the Boudreaus' permission to do so. [Note 8] The Boudreaus offered to contribute towards the cost, but the DiNinos refused their offer and paid for it themselves. Again, this was not an assertion of "right", but rather of generosity to their daughter and her family.

In 2013, the Boudreaus entered into a purchase and sale agreement with Mr. Newman for the sale of No. 2-4. Shortly before the closing, they approached Mr. Newman to see if he had any objection to their granting No. 6 an express easement to the disputed area prior to the sale. Mr. Newman refused to buy No. 2-4 if it was burdened with such an easement, and the Boudreaus dropped the idea, selling him the property without the easement.

In May 2014, Mr. Newman installed a fence on his property towards the back of the driveway to create a play area for his two young children. The corner of that fence made it impossible for vehicles to access No. 6's rear yard without traveling through the area occupied by the raised flower bed. Mr. Newman informed Ms. DiNino of the fence before it was installed, and she neither objected nor claimed to have any rights in the now disputed area. That dispute only arose after the fence was installed.

Further relevant facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

Ms. DiNino contends that she has a prescriptive right to use a 250-square-foot strip of the driveway located on 2-4 Victoria Terrace (the disputed area), and that Mr. Newman's fence unlawfully interferes with that right. I disagree. To the extent such a right existed before Mr. and Ms. DiNino owned both 6 Victoria Terrace and 2-4 Victoria Terrace, it extinguished when they acquired title to both properties. After the unity of title severed, the 6 Victoria Terrace residents' use of the disputed area was not adverse. Ms. DiNino thus has not met her burden to establish she has a prescriptive easement over Mr. Newman's land.

To be entitled to a prescriptive easement, a claimant must show "the (1) continuous and uninterrupted, (2) open and notorious, and (3) adverse use of another's land (4) for a period of not less than twenty years." [Note 9] White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 413 (2013). See also Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 4344 (2007); G.L. c. 187, § 2 ("No person shall acquire by adverse use or enjoyment a right or privilege or way or other easement from, in, upon or over the land of another, unless such use or enjoyment is continued uninterruptedly for twenty years."). The claimant has "the burden of proof on each and every element mentioned above." Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. "If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949).

Use prior to August 12, 1986

As previously discussed, [Note 10] a property owner "cannot have an easement in its own estate in fee." York Realty, Inc., 315 Mass. at 289. Thus, "[u]nder the common law doctrine of merger, easements are extinguished by unity of title and possession of the two estates [the dominant and the servient], in one and the same person at the same time.'" Williams Bros., 81 Mass. App. Ct. at 684 (quoting Ritger, 8 Cush. at 146).

To the extent Ms. DiNino and her husband, as the owners of 6 Victoria Terrace, had any easement interest in the disputed area before they purchased 2-4 Victoria Terrace, it extinguished when they bought that property on August 12, 1986 because they then owned both the dominant and servient estates. [Note 11] See Williams Bros., 81 Mass. App. Ct. at 684. Although title to those properties later severed on March 22, 1988 when the DiNinos gave 2-4 Victoria Terrace to the Boudreaus, that did not "revive" any easement that had been extinguished due to the merger of title. See id. at 684-685. After merger, any easement "must be created anew by express grant, by reservation, or by implication.'" Id. at 685 (quoting Cheever, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 607. Here, no owner of 6 Victoria Terrace acquired any express or implied easement right in 2-4 Victoria Terrace after the severance of title in March 1988. See n. 7, supra.

Use since March 22, 1988

Ms. DiNino contends that after title to 6 Victoria Terrace transferred to the Boudreaus on March 22, 1988, she acquired a prescriptive easement to use the disputed area. However, she has no such interest because her use was permissive; the Boudreaus allowed the DiNinos to use of their side of the driveway. "The rule in Massachusetts is that wherever there has been the use of an easement for twenty years, unexplained, it will be presumed to be under claim of right and adverse, and will be sufficient to establish title by prescription and to authorize the presumption of a grant unless controlled or explained." Truc v. Field, 269 Mass. 524 , 528-529 (1930). However, this presumption is overcome where, as here, there is "evidence of permission beyond mere acquiescence." Brooks, Gill & Co. v. Landmark Properties, 217 Ltd. P'ship, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 528 , 531 (1987) (citing Spencer v. Rabidou, 340 Mass. 91 , 93 (1959)). As further described below, the evidence of permission in this case not only overcomes the presumption of adversity, but affirmatively establishes that the Boudreaus permitted the DiNinos to use the disputed area.

"The essence of nonpermissive use is lack of consent from the true owner." Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145 (2000). The "intent or state of mind of the adverse claimant" is not determinative. Id. Rather, adversity "must be manifest by acts of clear and unequivocal character that notice to the owner of the claim might be reasonably inferred.'" Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 842 (2008) (quoting Jones, Easements, § 289, at 235 (1898)). "Whether a use is nonpermissive depends on many circumstances, including the character of the land, who benefited from the use of the land, the way the land was held and maintained, and the nature of the individual relationship between the parties claiming ownership." Totman, 431 Mass. at 145.

Here, the property at issue is, as Ms. DiNino admitted, a "common shared driveway" that was "intentionally shared" by the DiNinos and Boudreaus for over twenty-five years. Trial Tr. at 47-48. This shared arrangement where members of

both households would drive over it to reach their rear yards and park on the sides closest to their respective homes was deliberate and not at all hostile. The Boudreaus never objected to it. I infer that the Boudreaus did not simply acquiesce to the DiNinos' use of the disputed area, but, rather, they permitted it. See Dufault v. Lunsford, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1125 (2008), 2008 WL 2096091 at *1 & nn.3 & 5 (2008) (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) (concluding that inference "use was permissive and not being used under a claim of right" was proper because driveway was "intentionally shared").

The events preceding the Boudreaus' sale of 2-4 Victoria Terrace to Mr. Newman are further evidence that they permitted the DiNinos' use of the disputed area, and that the DiNinos used it by permission. Before the sale took place, the Boudreaus asked Mr. Newman if he would object to their placing an express easement on the disputed area for the benefit of No. 6. When Mr. Newman said that he would not purchase the property if such an easement existed, they quickly dropped the idea, and never mentioned anything about prescriptive rights. Had they believed such rights existed, they surely would have made such a disclosure. In light of Mr. Newman's objections, any failure to disclose would have been deception and, having observed the Boudreaus during their testimony, I do not believe them capable of such a thing.

The Boudreaus had reason to allow the DiNinos to use their part of the driveway, for their arrangement was mutually beneficial. The benefit to the DiNinos is clear using the Boudreaus' side of the driveway enabled them to park their vehicles behind their house. There is no indication that the DiNinos' use of the disputed area ever interfered with the Boudreaus' ability to use their land. Rather, it was advantageous to the Boudreaus because it alleviated their burden of maintaining their property. For example, the DiNinos had the driveway paved at their own expense, and Mr. DiNino helped maintain the entire driveway.

The way the disputed area was maintained further shows that the Boudreaus agreed to the DiNinos' use of it. The Boudreaus and DiNinos worked together to maintain the driveway members of both households shoveled snow, blew leaves, painted fences, and seal-coated the driveway. The DiNinos paid for it to be paved, but only after they consulted with the Boudreaus and obtained their permission to do so. They thus contributed towards its upkeep, but with the Boudreaus' consent.

The close family relationship between the Boudreaus and the DiNinos is also indicative of permissiveness. See Totman, 431 Mass. at 148 (noting that, although not dispositive, "evidence of a familial relationship may sometimes assist the fact finder in determining the individual nature of the relationship between the claimants or to whose benefit the land was used"); Dufault v. Lunsford, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1125 (2008), 2008 WL 2096091 at *1 (2008) (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) ("Although the judge did not find any direct evidence of a permissive use, the trial judge could reasonably infer permissiveness from his findings of a close and friendly relationship between the neighbors."). Ms. DiNino has resided at 6 Victoria Terrace with her daughter Maryann for over fifty years. The Boudreaus lived next door at 2-4 Victoria Terrace for over twenty-five years after Mr. and Ms. DiNino gave the property to them for "love and affection." From the time the Boudreaus took residence, they willingly shared the driveway with the DiNinos as it had been used since 1959 without issue. Evidently, they are a close family. Mr. DiNino's willingness to perform most of its maintenance, and his insistence on bearing the cost of having it paved, further reflect their close family tie.

Under these circumstances, I conclude that the Boudreaus permitted the DiNinos to use the disputed area. Because Ms. DiNino has not shown that her use of the disputed area was nonpermissive, she has not met her burden to establish that she has acquired a prescriptive easement over that area.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and declare that Ms. DiNino does not have a prescriptive easement over any portion of 2-4 Victoria Terrace, and that Mr. Newman is under no obligation to remove the fence on his property. Ms. DiNino's claim is thus DISMISSED, WITH PREJUDICE.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

Here, no owner of 6 Victoria Terrace ever reserved or acquired any express easement right in 2-4 Victoria Terrace after the severance of title in March 1988, nor did any easement arise by implication. No. 6 was not "landlocked" by the conveyance to the Boudreaus (and thus there was no easement by necessity). See Town of Bedford v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 76-77 (2004). Whether an easement by implication existed under the following doctrine "where, during the common ownership of a parcel of land an apparent and obvious use of one part of the parcel is made for the benefit of another part and such use is actually being made up to the time of severance and is reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of the other part of the parcel, then upon severance of the ownership a grant to continue such use may arise by implication,'" Id. at 78 (quoting Sorel v. Boisjolie, 330 Mass. 513 , 516 (1953)) might seem to be applicable, but not on the facts of this case. The question, as always when examining a claim of such an easement, is one of discerning the parties' intent from the circumstances. Id. at 76-77. I find they had no such intent, for at least three reasons. First, it would have been simple for the DiNinos expressly to reserve such an easement had they wanted to do so. They did not. Second, the use of the disputed area was not "reasonably necessary" for the enjoyment of No. 6. No. 6 had easy parking on the street in front of the house and, with removal of the raised flower bed alongside the house, enough land of its own to park there or, if desired, to use as an access driveway to parking in its back yard. See n. 1, supra. Third, as the sale negotiations with Mr. Newman showed (see discussion below), removing the disputed area from the exclusive possession of a third-party purchaser of No. 2-4 preventing it from being used as parking by the owners of No. 2-4, and from their ability to fence off that portion of their very small and tightly- constrained lot would either cause those potential buyers to go elsewhere or, at the least, significantly depress the sale price of the property. It was certainly never the DiNinos' intent to have their daughter and her husband face those consequences when the time came for sale.

DiNino would have paved this considerable additional area without first checking with the Boudreaus.

CONCETTA DININO, Trustee of the Concetta DiNino Irrevocable Trust v. ADRIAN NEWMAN

CONCETTA DININO, Trustee of the Concetta DiNino Irrevocable Trust v. ADRIAN NEWMAN