Abutting landowners, Alexander Parker and Joan Parker (Parkers), brought this action, pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 17, seeking to annul a special permit for construction of a sixteen-unit housing development for senior citizens granted to Brendon Homes, LLC and Brendon Properties, Inc. (Brendon Homes or defendants) by the Town of Carlisle Planning Board (Planning Board). The grant of the special permit is conditioned on Brendon Homes reserving a portion of the subject property as open space where public walking trails will be located, the deeding of the open space area to the Town of Carlisle (Town), and upon the reservation of a three-car parking area reserved for the public to provide access to the walking trails for public use. The Parkers, who would share a common driveway and an easement with the future residents of the development and with the public accessing the public parking area and trails, contend that the special permit will negatively impact their property, the surrounding neighborhood, and will overburden the easement.

The Parkers commenced this action on December 2, 2014. Their complaint opposing the special permit included five claims: 1) the Planning Board lacks the authority to issue the special permit, 2) the right of way easement is not properly addressed, 3) the special permit overburdens the right of way easement, 4) the special permit is injurious to the neighborhood, and 5) the proposed development will negatively impact their property value. Brendon Homes motion for judgment on the pleadings was allowed in part and denied in part by the court (Speicher, J) on May 27, 2015, dismissing Count 5, diminution in property value, as a separate count, while allowing the Parkers to offer evidence to show a diminution in value as to the issue of standing under G. L. c. 40A, § 17, provided such evidence is related to an interest protected by the Carlisle Zoning Bylaws (Bylaw).

I took a view of the Parkers property and the subject property on March 28, 2016, and a trial was held before me on March 29 and 30, 2016. After the receipt of transcripts and the filing of post-trial memoranda and requests for rulings of law and findings of fact from both sides, I took the matter under advisement on June 24, 2016.

For the reasons stated below, I find that the Parkers enjoy a presumption of standing as abutters, the defendants have successfully rebutted that presumption, and all but one of the Parkers claims of aggrievement are too speculative and unsubstantiated to confer standing under G. L. c. 40A, § 17. The Parkers have made a showing of aggrievement based on the proposed public use of the easement over their property, sufficient to confer standing. While the Planning Board did not exceed its authority generally in granting the special permit for the development, it did exceed its authority in conditioning the special permit on a requirement that the developer provide public access over land including the Parkers land, for public parking and trail access. Therefore, the Planning Boards decision is annulled and this matter is remanded so that the Planning Board may consider whether or not to affirm its grant of the special permit without requiring public access over the Parkers property that is subject to the right of way easement, or whether the special permit may be modified in some other way so as to provide public access to the subject property in a way that does not permit public access over the Parkers property.

FACTS

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence admitted at trial, my view of the subject properties, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, weight and inferences reasonably to be drawn from the evidence admitted at trial, I make factual findings as follows:

1. Brendon Homes is the purchaser pursuant to a purchase and sale agreement with Edward Talbot, Jr. (Talbot), for property owned by Talbot at 81 Russell Street in Carlisle (Subject Property).

2. Plaintiffs Alexander and Joan Parker own and reside at property at 77 Russell Street in Carlisle, abutting the Subject Property.

3. The Parkers property and the Subject Property share a common driveway that provides access to both properties from Russell Street. The common driveway is partly on the Parkers property and is partly on land owned by Talbot on the Subject Property.

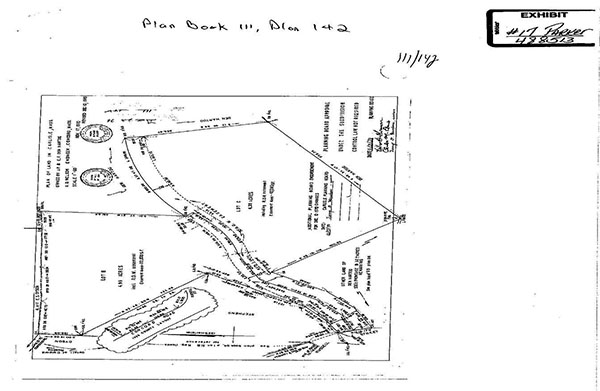

4. Both the Parkers property and the Subject Property derive from a common grantor, Jacob and Elizabeth Den Hartog (Den Hartogs). In 1970, the Den Hartogs subdivided their property into three lots, Lots A, B, and C. Lots B and C are shown on a plan entitled Plan of Land in Carlisle, Mass. owned by J.P. and E.F. Den Hartog, dated November 17, 1970 (1970 Plan). Lots B and C, shown on the 1970 Plan, attached here as Exhibit A, contained 4.99 acres of land and 6.35 acres of land, respectively. Lot A, not depicted on the 1970 Plan, is referred to on the 1970 Plan as Other Land of Den Hartog, and is described as containing 32 acres, more or less. The subdivision left Lot A, now part of the Subject Property, without useable frontage on and access to Russell Street (due to intervening wetlands), but for the right of way easement described in the following paragraph. [Note 1]

5. By a deed dated and recorded on December 23, 1970 with the Middlesex North District Registry of Deeds (Registry) in Book 1945, Page 206 (1970 Deed), the Den Hartogs deeded Lots B and C to Alexander Parker, reserving a ROW Easement . . . across a strip of the granted premises . . . for use by the grantors, their heirs, assigns and successors in title for the purposes of ingress and egress with motor vehicles or otherwise to other land of the grantors. The right of way easement reserved for the benefit of the Den Hartogs remaining land (Lot A) is approximately fifty feet wide beginning at the Subject Property and traversing sections of Lots B and C, ending at Russell Street. The right of way easement occupies 64,280 square feet of land, 22,000 square feet of which is a part of Lot B and 42,280 square feet of which is part of Lot C.

6. In addition to reserving to the Den Hartogs, for the benefit of their remaining land, rights of access and egress over Lots B and C, the 1970 Deed also reserved to the Den Hartogs, for the benefit of their remaining land, the right to develop and construct a road over the

easement area, as shown on said plan, for acceptance by the Town of Carlisle as a public way. [Note 2]

7. Contemporaneously with the 1970 Deed, the Den Hartogs entered into an agreement with Mr. Parker acknowledging that the SELLER has retained an easement over said premises . . . for purposes of ingress and egress to other land of the SELLER and for contemplated future construction of a road over the easement area for acceptance by the Town of Carlisle as a public way. The agreement, recorded with the Registry on December 23, 1970 in Book 1945, Page 213, further granted the Den Hartogs the right to purchase back those parts of Lot C that are within the right of way easement [a]t the time

that the contemplated road is accepted by the Town of Carlisle as a public way, . . . [Note 3]

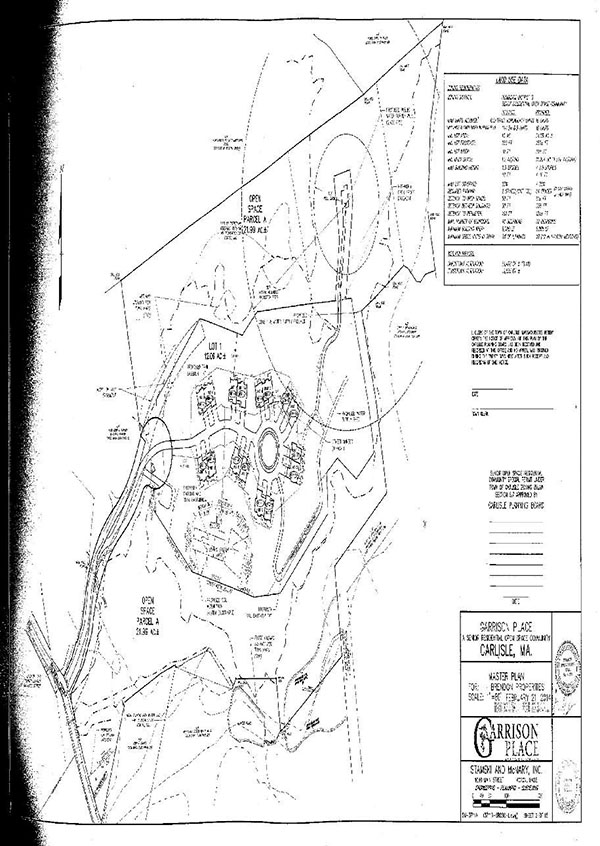

8. On May 10, 1978, with deeds recorded consecutively, the Den Hartogs deeded their remaining thirty-two acres of land (Lot A) to Edward J. Talbot, and Alexander Parker conveyed Lot C to Talbot. The deeds (hereinafter the 1978 Deeds) were recorded with the Registry in Book 2301, Page 415 and Book 2301, Page 420, respectively. The deed of Lot C from Parker to Talbot also granted to Talbot, for the benefit of Lot C, the right and easement in common with the grantor and others entitled thereto, to pass and repass over a strip of Lot B . . . with motor vehicles and otherwise and to develop and construct a driveway over said strip. With this grant, Talbot, as the owner of Lot A and Lot C, now possessed an identical right of way easement for the benefit of both Lots A and C over a portion of the Parkers property. The deed for Lot C also provided that once the driveway was constructed, and once a dwelling was constructed on the Parkers property (Lot B), the owners of Lot B, and the owner of Lots A and C would share equally in the cost of

maintaining the common driveway until such time as a road has been constructed over the easement granted hereby and such road has been accepted by the Town of Carlisle as a public way. [Note 4]

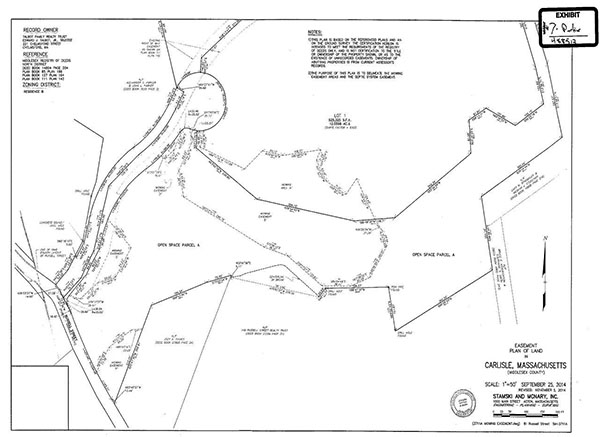

9. The right of way easement is also shown on a plan entitled Easement Plan of Land in Carlisle, Massachusetts revised through November 5, 2014, a portion of which is attached here as Exhibit B. [Note 5]

10. On October 23, 1978, Talbot applied for a special permit to construct a common driveway that would occupy the right of way easement. In connection with the approval of the common driveway special permit, Parker and Talbot entered into a maintenance agreement (1978 Maintenance Agreement) dated October 23, 1978 and recorded on September 20, 1979 in the Registry in Book 2385, Page 485. The 1978 Maintenance Agreement provided that Talbot and Parker, their heirs, successors and assigns have the right to use the driveway in common for all purposes for which private driveways are customarily used in the Town of Carlisle. The Maintenance Agreement further provided, consistent with the deed from Parker to Talbot, that Talbot, as the owner of Lots A and C, and Parker, as the owner of Lot B, and their successors, would share equally in the cost of repairing, maintaining and removing snow from the common driveway until such time as a road has been constructed and accepted by the town as a public way over the driveway

built over the easement and that part of Lot C where the driveway is located. [Note 6]

11. The existing private driveway is approximately 10 to 12 feet wide. It is in poor condition with the pavement broken in places, and flooding occasionally occurring during heavy rainfall periods. Flooding is attributed to a culvert located under the driveway that is not large enough to allow the water to pass beneath the road. [Note 7]

12. On February 24, 2014, Brendon Homes, as the buyer of Lots A and C under a purchase and sale agreement with Talbot, applied for a Senior Residential Open Space Community (SROSC) special permit with the Planning Board, pursuant to § 5.7 of the Bylaw, to construct a senior residential development on the Subject Property. [Note 8]

13. The SROSC special permit was adopted by the Town in 1995 and revised in 2011. Section 5.7.4 of the Bylaw lists a series of requirements for the Planning Board in connection with the issuance of a special permit for a SROSC:

(1) That the number of dwelling units will be no greater than 1.5 times the number of lots which the Planning Board, incorporating wetland considerations, determines would be allowed on the parcel were it to be developed as a subdivision according to the Rules and Regulations for the Subdivision of Land in Carlisle; but that the number of dwelling units will not exceed one half the number of acres in the tract.

(2) That the total number of dwelling units permitted under this bylaw has not exceeded 3% of the total number of constructed dwelling units in the Town.

(3) That the total tract area is at least 10 acres.

(4) That the width of any lot shall be at least 40 feet between the point of physical access on a way which is acceptable for frontage under Chapter 41 and any building containing a dwelling unit.

(5) That the entire Senior Residential Open Space Community tract is separated from adjacent property by intervening Open Space.

(6) That the Open Space shall constitute at least 1.2 acres for every dwelling unit.

(7) That the Open Space meets at least one of the following criteria:

1. It preserves some component of Carlisles farm community, such as agricultural fields.

2. It preserves areas of open meadow, woodland, water bodies or ecotone.

3. It creates or preserves vistas or buffer areas.

4. It preserves valuable habitat for identifiable species of fauna and flora.

5. It preserves an artifact of historic value.

(8) That the Open Space is of such shape, size and location as are appropriate for its intended use. In making this finding, the Planning Board may find it appropriate that the Open Space be used, in part, to create a visual buffer between the Senior Residential Open Space Community and abutting uses, and for small structures associated with allowed uses of the Open Space.

(9) That the Open Space does not include any residential structures, or any appurtenant structures such as carports, septic systems, roads, driveways or parking, other than those which the Planning Board may allow under § 5.7.4.8 above.

(10) That the Open Space shall be conveyed to the Town of Carlisle for park or open space use, or conveyed to a non-profit organization the principal purpose of which is the conservation of open space, or conveyed to a corporation or trust composed of the owners of units within the Senior Residential Open Space Community. In the case where such land is not conveyed to the Town, the Board must find that beneficial rights in said Open Space shall be deeded to the owners, and a permanent restriction enforceable by the Town pursuant to M.G.L. Ch. 184, Section 32, providing that such land shall be kept in open or natural state, shall be recorded at the Middlesex North District Registry of Deeds.

(11) That access from a way, of suitable width and location, has been provided to the Open Space.

(12) That the Senior Residential Open Space Community will be composed of attached dwelling units which nevertheless reflect, in size and architecture, the character of Carlisles single family residences. The buildings shall not have the appearance of apartments.

(13) That each building in the Senior Residential Open Space Community has no more than four dwelling units, averaging no more than two bedrooms each, that no unit has more than three bedrooms, and that no building measures more than 6,000 square feet. This calculation includes the area within the building that may be devoted to garage spaces.

(14) That all residential buildings have safe access from ways.

(15) That provision has been made for at least two parking spaces per unit inclusive of any garage spaces.

(16) That all residential buildings are located at least 100 feet from the boundary of the land subject to this special permit, and least 50 feet from the Open Space, and at least 30 feet from other residential buildings.

(17) That a Homeowners Association will be formed which will have the legal responsibility for the management and maintenance of the development. This responsibility includes but is not limited to exterior maintenance of buildings, plowing, driveway, parking lot and road maintenance, landscape maintenance, and maintenance of common utilities, including septic systems and wells. In addition, the Homeowners Association must accept responsibility for the maintenance of the Open Space if the Open Space is to be conveyed to a corporation or trust either of which is composed of unit owners.

(18) The following age restrictions shall apply:

1. That each dwelling unit shall have in residence at least one person who has reached the age of 55 within the meaning of M. G. L. c. 151B section 4, paragraph 6, and 42 USC section 3607(b)(2)(C).

2. That no resident of a dwelling unit shall be under the age of 18.

3. That in the event that there is no longer a qualifying resident of a unit, a two-year exemption shall be allowed for the transfer of the unit to another eligible household pursuant to Section 5.7.4.18.

4. All condominium deeds, trusts or other documents shall incorporate the age restrictions contained in this Section 5.7.4.18. [Note 9]

14. The Planning Board has adopted Rules and Regulations for the administration of SROSC special permits. The Rules and Regulations include a requirement that a traffic study is to be conducted in connection with a SROSC special permit application only where the proposed project will generate an average of at least 100 additional vehicle trips per weekday, as determined from the most recent edition of the Institute of Transportation Engineers publication Trip Generation. (ITE Manual) [Note 10] The most recent edition of the ITE Manual is the 9th edition, issued in 2012.

15. The proposed development, to be known as Garrison Place, consists of sixteen condominium units on a 12-acre parcel, with an additional 22 acres of land being reserved to the Town for public walking trails and open space. Each condominium unit is proposed to be a two-bedroom unit, with a two-car garage and two additional outdoor parking spaces. Also proposed is a three-space parking lot towards the entrance of the development for the public to park and access the walking trails to be constructed on the 22-acre open space parcel. Each condominium unit must have at least one resident over the age of 55. A plan of Garrison Place is attached hereto as Exhibit C. [Note 11]

16. The open space parcel is to be deeded to the Town, subject to an easement and obligations of the condominium association of Garrison Place, which will be to mow and maintain the open space, vistas, and fields. [Note 12]

17. Access to the new development, including to the public parking and the publicly accessible walking trails, will be over the existing common private driveway, located over the existing right of way easement, including the portion of the right of way easement that is on the Parkers property. [Note 13]

18. As proposed, the reconstructed driveway to Garrison Place will continue to be a private driveway, with no plans for the Town to accept it as a public way, provided that it will be subject to the publics ability to park in the three-vehicle parking area and to access the walking trails. [Note 14]

19. The Planning Board held hearings on the SROSC special permit application on March 10, March 24, April 14, May 12, June 9, July 14, August 11, September 8, September 29, October 20, and November 10, 2014.

20. On November 10, 2014, the Planning Board voted unanimously to grant the SROSC special permit. The decision was filed with the Town clerk on November 12, 2014 (the Decision). In its decision, the Planning Board made detailed findings with respect to compliance of the Garrison Place development with the requirements in Section 5.7.4 of the Bylaw. The Planning Board also imposed conditions on the grant of the special permit, including the following:

16. The proposed on-site trail parking area and mailbox delivery site shall be paved, handicapped accessible, and plowed and maintained by the Condominium Association

17. The proposed trail is to be constructed on Open Space Parcel A and within the trail easements by the Town through its Trails Committee after Parcel A is conveyed to the Town.

18. The Town, acting through its Trails Committee, may install and maintain a kiosk for display of trail information and signage for trail users adjacent to the trail parking area.

19. When complete, the proposed on-site trail parking area and all portions of the trail on the applicants property shall be open to the public from dawn to dusk. [Note 15]

21. The Parkers timely filed their complaint on December 2, 2014, appealing the decision of the Planning Board.

DISCUSSION

The Parkers appeal the Planning Boards approval of Brendon Homes SROSC special permit under G. L. c. 40A, § 17. They argue that the new development will cause increased traffic, noise, congestion, and destruction of their private setting in Carlisle. In addition, they contend that the use of the right of way easement for the development effectively takes a portion of the Parkers land and impermissibly allows the public onto the Parkers property. The defendants argue that the Parkers have not demonstrated any of the harms they claim they will suffer, and that the use of the right of way easement as proposed does not overburden the easement or otherwise infringe on the Parkers rights.

The threshold question that I must decide is whether the Parkers are aggrieved by the grant of the SROSC special permit, and thus, possess standing to appeal the Planning Boards Decision. Standing presents a question of the subject matter jurisdiction of the court that must be resolved before proceeding to the merits. Planning Bd. of Marshfield v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Pembroke, 427 Mass. 699 , 703 (1998); BAC Home Loans Serv. LP v. Kay, 21 LCR 50 , 50 (2010) (Standing is a matter of subject matter jurisdiction.); U.S. Bank, Nat. Assn v. Sarourim, 20 LCR 151 , 151 (2010). Without a showing of aggrievement, the court has no jurisdiction to hear the dispute and reach the substantive issues in the case. Monks v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 37 Mass. App. Ct. 685 , 687 (1994) (subject matter jurisdiction is a prerequisite to judicial review).

STANDING

General Laws c. 40A, § 17 provides in relevant part that [a]ny person aggrieved by a decision of

any special permit granting authority

may appeal to the land court department. Abutters to the subject property are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they are aggrieved persons within the meaning of § 17. 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012); Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Choate v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Mashpee, 67 Mass. App. Ct. 376 , 381 (2006). If standing is challenged, the jurisdictional question is decided on all the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiffs from the presumption. Marashlian, supra, 421 Mass. at 721, quoting Marotta v. Bd. of Appeals of Revere, 336 Mass. 199 , 204 (1957).

The party challenging the plaintiffs presumption of standing as an abutter can do so by offering evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, supra, 461 Mass. at 700, quoting Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 258 (2003). If a defendant offers enough evidence to warrant a finding contrary to the presumed fact, the presumption of aggrievement is rebutted, and the plaintiff must prove standing by putting forth credible evidence to substantiate the allegations. Id. at 701. On the other hand, if a defendant fails to offer sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption of standing, then the abutter is deemed to have standing, and the case proceeds on the merits. Id.

If the plaintiffs presumption of standing is rebutted, the plaintiff bears the burden to present evidence establishing that he or she will suffer some direct injury to a private right, private property interest, or private legal interest as a result of the decision that is special and different from the injury the decision will cause to the community at large, and that the injured right or interest is one that G. L. c. 40A or the Bylaw is intended to protect. Id. at 700; Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 120 (2011); Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 27-28 (2006); Marashlian, supra, 421 Mass. at 721; Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005); Barvenik v. Board of Alderman of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132-133 (1992); Ginther v. Commr of Ins., 427 Mass. 319 , 322 (1998). In other words, if the presumption is rebutted, the Parkers bear the burden of proving, by direct facts and not speculative evidence, that they would suffer a particularized injury as a consequence of the Planning Boards decision to issue the special permit. Kenner, supra, 459 Mass. at 120. Aggrievement is not defined narrowly; however, it does require a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm. Id. at 121-123 (finding the height of a new structure to have a de minimis impact on plaintiffs ocean view). The facts offered by the plaintiff must be more than merely speculative. Sweenie v. A. L. Prime Energy Consultants, 451 Mass. 539 , 543 (2008).

Since the Parkers property abuts the Subject Property on which the development will occur, the Parkers benefit from the presumption of aggrievement. To rebut this presumption, the defendants introduced evidence in the form of testimony from George Dimakarakos (Dimakarakos), a civil engineer with expertise in hydrology who was the principal engineer for the Garrison Place project, and Jeffrey Bandini (Bandini), a transportation engineer. First, Dimakarakos testified that the proposed development will not cause injury to the Parkers property through flooding or water runoff. [Note 16] Dimakarakos also testified that the discharge from

the septic systems for Garrison Place will flow south of the development towards Russell Street and not in the direction of the Parkers property. [Note 17] Further, he attested to features of the new access roadway (located near a wetland and presently has an inadequately sized culvert), including its changed geometry and culvert improvements that will help to manage stormwater surges and prevent flooding over the access driveway where it passes the Parkers property. [Note 18] Dimakarakos noted that under the terms of the SROSC special permit, offsite work is also to be done on Russell Street in order to mitigate existing flooding impacts and to address safety issues, by installing culverts and a guardrail. [Note 19]

In addition, he examined the potential impact the proposed public water supply could have on the Parkers well water. Dimakarakos testified that the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) issued a permit to install a testing well at the Subject Property at the location of the proposed well site where an assessment of the public water supply is to be done to determine the quantity and quality of water available. The approval of the Planning Board is subject to the requirement that the project proponent obtain a public well permit from DEP. Whether DEP issues such a permit will be dependent on whether the applicant can demonstrate, as a result of the testing it has been authorized to perform, that water is available of sufficient quantity and quality. The Parkers private well is located sufficiently far away from the test well site that no testing is required by DEP with respect to the Parkers well. [Note 20] If the testing, yet to be completed pending this appeal of the special permit, does show a lack of water available at the Subject Property, the applicant would have to obtain approval for a public water supply well at another location, or the project would not be able to go forward.

Brendon Homes also submitted to the Planning Board a limited traffic study for the purpose of demonstrating that the proposed development would not generate sufficient new vehicle trips to trigger the requirement for a full traffic study. As required by the Planning Boards Rules and Regulations, Brendon Homes based its submission with respect to the number of expected vehicle trips on the ITE Trip Generation Manual, 9th edition (2012). Dimarkarakos testified that the ITE Manual, besides being required by the Planning Boards Rules and Regulations, provides industry-standard statistics, based on frequently updated actual traffic counts with respect to traffic generated by different uses of land. Dimakarakos testified that the closest and most appropriate classification in the ITE Manual to the proposed development was Land Use Code 251 (Senior Adult Housing - Detached). The study included analysis of vehicle trip generation for estimated vehicle counts based on estimates in the ITE Manual. [Note 21] The limited traffic study submitted to the Planning Board concluded that the common driveway would likely produce an average of 69 trips per weekday, including 50 additional trips from the development and 19 trips generated by the Parkers property (and the Talbot house being removed from the Subject Property). [Note 22] Per the Planning Boards Rules and Regulations regarding SROSC special permits, Dimakarakos opined that a full traffic study was not necessary or required since the additional trips generated by the development were fewer than 100 trips per weekday. [Note 23] The Planning Board accepted this finding that the proposed development would not generate as many as 100 vehicle trips per weekday.

Jeffrey Bandini, a transportation engineer who has conducted and peer reviewed several traffic studies with respect to residential housing, concluded that the SROSC would not create any undue or excessive traffic concerns that would impede the Parkers use and enjoyment of their property. [Note 24] Bandini personally peer reviewed the limited traffic study done by Dimakarakos and testified that it was done in conformance with standard practice, including the use of the 9th edition of the ITE Manual. He concurred with Dimakarakos assessment that the number of trips identified for trip generation fell below the threshold 100 trip requirement used by the Planning Board to determine when a full traffic study would be required. He further opined that Land Use Code 251 for Senior Adult Housing Detached, was the only appropriate ITE code that would be applicable to the Garrison Place development. [Note 25]

The limited traffic study considered by and accepted by the Planning Board also addressed sight distances for turning movements to and from the proposed common driveway, as well as safe stopping sight distancesthe sum of the distance traveled while the driver reacts to an object necessitating a stop and the distance it takes for the vehicle to stop once the brakes are applied. The distances used in the analysis were based on the 30 m.p.h. posted speed limit on Russell Street. [Note 26] Based on the sight distance analysis provided to the Board, Brendon Homes agreed to provide, and the Planning Board agreed to require, as part of the development, regrading of the shoulder of Russell Street to allow for clearer, longer sight lines from the common driveway and to improve safe travel along Russell Street at speeds approaching 30 m.p.h. No mitigation was determined to be needed to achieve permissible stopping sight distances. [Note 27]

Dimakarakos also testified with respect to the analysis done in regards to the possible impact on the Parkers property of lights from headlights from vehicles entering and leaving Garrison Place. As a result of discussions during hearings and site visits with the Planning Board, and based on visual observations made in the field, despite Brendon Homes contention that there was significant existing vegetation, Brendon Homes agreed to additional plantings to mitigate any potential visual impacts. [Note 28] With respect to other potential impacts on the Parkers, there was testimony that utility lines to be installed underground through and along the right of way easement will not cause any damage or injury to the Parkers property. [Note 29] Lastly, Brendon Homes offered testimony with respect to the visibility of the development from the abutting properties. Though an assessment from the Parkers property was not done, one was done for the property directly across from the proposed development on Russell Street. From this perspective, only one of the units was primarily visible. Dimakarakos testified that the design of the development and placement of the units was accomplished so that it would appear to onlookers from Russell Street as much as possible, to be a single-family house. [Note 30] Given the significant distance of the development from Russell Street and amount of property that is to remain wooded, this is a reasonable contention and I credit this testimony.

I find that the foregoing evidence and testimony is more than sufficient to cause the Parkers presumption of standing to recede; the question now to be decided on all the evidence. See Standerwick, supra, 447 Mass. at 34-35. I now consider whether the Parkers have proffered sufficient evidence to substantiate their allegations of harm and have shown that the injury complained of is to an interest the zoning scheme seeks to protect. Id. at 32. To support their contention that they have offered sufficient credible evidence of harm, the Parkers offer the testimony of plaintiff Joan Parker and Paul Flaherty. The defendants contend that the Parkers have not made any credible showing of actual harm and that any evidence of injury to their property offered by the Parkers is speculative. In all respects but one, the defendants are correct.

Mrs Parker testified on a range of concerns, and her testimony was generally vague, speculative and unsubstantiated, and was in other respects unqualified. See Sweenie, supra, 451 Mass. at 545-546; see generally Barvenik, supra, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 (1992). Mrs. Parker, who acknowledged that she has no qualifications as a traffic expert, testified that there would be more traffic at the proposed development than the number of trips accepted by the Planning Board, and based her testimony on her own anecdotal recounting of the amount of traffic generated by her own home. She testified that she had concerns about interference with the operation of the private well on her property as a result of the drilling of a public water supply well on the Subject Property, but could offer no qualified, non-speculative testimony as to the reasons for such concern. She in fact acknowledged that despite her concerns about the well, she does not have any factual basis for her concerns. [Note 31]

Mrs. Parker gave extremely vague testimony to the effect that the development would have a negative impact on the value of her property, but without attributing the negative impact to any particular aspect of the development and without offering any opinion as to the extent of the impact. [Note 32] Diminution in the value of real estate is a sufficient basis for standing only where it is derivative of or related to cognizable interests protected by the applicable zoning scheme. Kenner, supra, 459 Mass. at 123. Where Mrs. Parkers opinion regarding the diminution in value of her property is not tethered to a specific injury, it cannot provide an independent basis for standing.

Furthermore, even if it had been tied to a legally cognizable interest, Mrs. Parkers opinion as to loss of value was insufficient to create a dispute of fact because, testifying as an owner, she failed to offer sufficient support for her opinion. A nonexpert owner of property may testify to its value upon the basis of his familiarity with the characteristics of the property, his knowledge or acquaintance with its uses, and his experience in dealing with it. Epstein v. Board of Appeal of Boston, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 752 , 759 (2010), quoting from Winthrop Prods. Corp. v. Elroth Co., 331 Mass. 83 , 85 (1954). Here, Mrs. Parker did not offer any explanation of her qualifications (other than being an owner) or her familiarity or experience, or any basis for her opinion or facts in support for her opinion beyond a bare assertion that there would a loss of value of unspecified amount. [W]hether an owner, or any other witness, is sufficiently qualified to offer an opinion as to the value of real property is a question committed to the judge's sound discretion. Canepari v. Pascale, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 840 , 847 (2011). Here, Mrs. Parker has offered no basis at all for her opinion that there will be a diminution in the value of her property; I disregard her opinion as speculative and insufficient to create a question of fact, even with the benefit of all reasonable inferences. Moreover, even accepting for purposes of this trial that such a diminution in value would occur (which I do not), Mrs. Parker has failed to relate this decrease in value to any legally cognizable injury. Accordingly, I am constrained to disregard her opinion that there will be a decrease in the value of her property, and that such decrease would be the result of an injury to a protected interest occasioned by the approval and construction of the Garrison Place development.

The plaintiffs also presented the testimony of Paul Flaherty, who was presented as an expert, with the intention of discrediting the Planning Boards acceptance of the trip generation figures in the ITE Manual that were used to determine that the number of trips generated by the proposed development would be less than 100, and therefore, under the Planning Boards Rules and Regulations, would not require the applicant to conduct a full traffic study. Mr. Flaherty acknowledged that he has no education, training or experience as a traffic engineer, and further acknowledged that this case was his first experience with the ITE Manual. Nevertheless, he was offered as an expert to opine that the Planning Boards acceptance of numbers derived from the ITE Manual, for the purposes of determining the number of trips that would be generated by the proposed project, was incorrect. His testimony was further offered for the proposition that the ITE Manual itself incorrectly determined the number of trips attributable to the use classification used by the Planning Board. While his testimony was going to be offered to refute Dimakarakos and Bandinis use and application of the ITE Manual, as required by the Planning Boards Rules and Regulations, he testified he had no experience in dealing with the ITE Manual or with the

standards upon which the ITE established the land use classifications in its manual. [Note 33] Flaherty was not only going to challenge the validity of the ITE, but the use category applied to the SROSC under Land Use Code 251 (Senior Adult Housing - Detached). Whatever qualifications Flaherty might have in other fields, he was not qualified to testify with respect to the subject for which his testimony was offered, and I so ruled at trial. Even if Flaherty had been qualified, I would not have given weight to this testimony. The Planning Boards Rules and Regulations explicitly direct applicants to use the latest edition of the ITE Manual in evaluating the trip generation for proposed projects. The Parkers failed to demonstrate by any competent testimony that this requirement was arbitrary or otherwise unreasonable. Moreover, Dimakarakos and Bandini both testified without contradiction that the ITE Manual is commonly accepted in the industry and relied on not only by engineers, but also by planning boards and zoning boards. [Note 34]

The concerns of the Parkers described above are too speculative and remote to grant them standing on such grounds. Caso v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Natick, 7 LCR 293 , 296 (1999) ([F]or an increase in traffic to constitute a source of aggrievement a plaintiff in a zoning appeal must show that the increase will adversely affect a protected property interest.); Cohen v. Plymouth Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 25 Mass. App. Ct. 619 , 623 (1993) (requiring more than allegation of increased traffic to show specific injury).

Mrs. Parker raised other aggrievements that were only supported by her own opinions, which I find to be either unqualified, speculative, or both. These aggrievements include harm from fumes created by the additional traffic, headlights from traffic, poor sight lines in the driveway and Russell Street, impact to view, flooding, and detriment to the character of the neighborhood. [Note 35] The Parkers submitted no expert or other qualified testimony, reports, or studies as to these potential impacts.

Notwithstanding the Parkers failure to demonstrate their standing with respect to the issues described above, I find that the Parkers have offered sufficient evidence of an injury to a cognizable interest to confer standing. The Decision of the Planning Board is conditioned on the provision of public access to a three-vehicle parking area and publicly accessible walking trails on the Garrison Place property. Access to the parking area and to the walking trails is over the common driveway to be constructed on the right of way easement, part of which lies on the Parkers property. Whether or not the amount of traffic generated by this public use of their property will physically interfere with the Parkers use of their property, the Planning Boards Decision effectively requires the Parkers to contribute their property to a public use, and to do so while they remain obligated to share in the cost of repairing, maintaining and plowing the right of way easement.

Unless the right of way easement authorizes public use of the right of way easement as part of the rights granted to the owner of the dominant estate, the forcing of public access on the Parkers property by the Planning Board and Brendon Homes is a cognizable injury that supports a finding of aggrievement for purposes of establishing the Parkers standing. Mrs. Parker expressed this concern about the public use of her property by members of the public seeking access to the parking area and the trails on the Garrison Place property. She testified that she was concerned that people looking for the trail heads would mistakenly drive up her driveway, that based on her observations of other trail heads, the three-car limit for the trail head parking area would be inadequate and unenforceable, and that there likely would be a great deal of traffic related to public use of the trails. [Note 36] I find these concerns to be neither unqualified, nor speculative. The Parkers, as the owners of the servient estate on the right of way easement, contend that public access is not contemplated by the grant of the easement and that it will overburden the right of way easement. Imposing public use on a private right of way may constitute an injury to the owner of the servient estate by amounting to a public taking of private property without compensation, or by constituting an overburdening of an easement that was intended to be limited to private access only. Southwick v. Planning Bd. of Plymouth, 365 Mass. App. Ct. 315 (2005) (Subdivision approval annulled where subdivision roadway extended over existing easement for which subdivision owner had no rights); Goff v. Town of Randolph, No. 15-P-1144, 2016 WL 4268381 (Mass. App. Ct. August 12, 2016) (Rule 1:28) (Plaintiff had standing to challenge use of private way, partly over his land, to access public park). Contra, Picard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Westminster, 474 Mass. 570 , 574-575 (2016) (holding owner of dominant estate lacked standing to bring zoning appeal based on mere ownership of easement and where complained-of construction did not interfere with plaintiffs exercise of easement rights over the servient estate). Accordingly, based on the potential overburdening of the right of way easement over the Parkers property, I find that the plaintiffs have established their standing.

By virtue of their rights in the deeded right of way easement and ownership of the servient estate, the Parkers have made a showing that their legal rights likely will be infringed and their property interests adversely affected. The Parkers have standing on these grounds. The impacts of the public access are discussed further in the context of the merits of the Planning Boards Decision below.

THE MERITS

The courts inquiry in reviewing a decision of a board of appeals or planning board granting zoning relief is a hybrid requiring the court to find the facts de novo, and, based on facts found by the court, and not those found by the board, to affirm the boards decision unless it was based on a legally untenable ground, or was unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary. MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 639 (1970). This is a two-part inquiry requiring the court to first determine whether the boards decision was based on a legally untenable ground. A legally untenable ground is a standard, criterion, or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws. Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003). Only after determining that the decision was not based on a legally untenable ground does the court consider, on a more deferential basis, whether any rational view of the facts the court has found supports the board's conclusion

Sedell v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Carver, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 450 , 453 (2009), quoting Britton, supra, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 75. The court may not overturn the boards decision unless no rational view of the facts the court has found supports the [zoning boards] conclusion

Id. at 74-75.

General Laws c. 40A, § 9 provides the statutory framework for granting or denying special permit applications. Special permit procedures have long been used to bring flexibility to the fairly rigid use classifications of Euclidean zoning schemes by providing for specific uses which are deemed necessary or desirable but which are not allowed as of right. SCIT, Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Braintree, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 101 , 109 (1984) (internal citations omitted). General Laws c. 40A, § 9 requires the Planning Board to make a detailed record of its proceedings and to set[ ] forth clearly the reason for its decision. The Supreme Judicial Court has noted that [i]t is a strong protection against hasty, careless, or inconsiderate action to require a public board to put in writing a full statement of its reasons for action. Board of Aldermen of Newton v. Maniace, 429 Mass. 726 , 732 (1999), quoting Bradley v. Board of Zoning Adjustment of Boston, 255 Mass. 160 , 173 (1926). The filing of a decision without findings has been scorned as an expensive, time consuming, empty gesture requiring a remand. Board of Aldermen of Newton v. Maniace, 45 Mass. App. Ct. 829 , 833 (1998). A mere repetition of statutory words fails to satisfy the requirements of G. L. c. 40A, § 9. Josephs v. Board of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 , 295 (1972). [T]here must be set forth in the record substantial facts which can rightly move an impartial mind, acting judicially, to the definite conclusion reached. Gaunt v. Board of Appeals of Methuen, 327 Mass. 380 , 381 (1951).

The Parkers contend that Planning Board exceeded its authority in issuing the special permit by failing to consider the impact of the development on the right of way easement over the Parkers property. These allegations require the court to examine the right of way easement to determine the parties legal rights and interests in the easement before determining whether the Planning Board acted outside the scope of its authority.

When interpreting deeds and written conveyances of easements, the court is to consider the language of the written instrument and, when necessary, construe it in light of the relevant attendant circumstances that existed at the time of the instruments creation. Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998); Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007); Mugar v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Auth., 28 Mass. App. Ct. 443 , 444 (1990). When the language of the applicable instruments is clear and explicit, and without ambiguity, there is no room for construction, or for the admission of parol evidence, to prove that the parties intended something different. Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. 526 , 7 Cush. 526 , 528 (1851); accord Panikowski v. Giroux, 272 Mass. 580 , 582, 172 N.E. 890 (1930); Westchester Assocs., Inc. v. Boston Edison Co., 47 Mass. App. Ct. 133 , 135, 712 N.E.2d 1145 (1999). The extent of [the] easement . . . is fixed by the conveyance, and the language [used]...is the primary source for the ascertainment of the meaning of [the] conveyance. Sheftel, supra, 44 Mass. App. Ct. at 179, quoting Restatement of Property §§ 482, 483(d) (1944). [T]he words themselves remain the most important evidence of intention. Robert Indus., Inc. v. Spence, 362 Mass. 751 , 755 (1973).

The right of way easement was originally created as part of the sale of Lots B and C by the Den Hartogs to Alexander Parker. The Den Hartogs reserved the right of way easement to preserve access for their remaining land (later designated as Lot A) to Russell Street, a public way. Although the Den Hartogs remaining land had frontage on Russell Street after the conveyance, it was not useable frontage because of the existence of wetlands. The explicit language of the easement as set forth in the 1970 Deed states that the right of way is for use by the grantors, their heirs, assigns and successors in title for the purposes of ingress and egress with motor vehicles or otherwise to other land of the grantors. [Note 37] This language is plain and unambiguous, and therefore, there is no need to look outside the four corners of the deed to surmise the intent of the parties. The general language indicates that the use of the right of way easement over Lot B is unrestricted and may be used for ingress and egress by the grantors and their successors to Lot A for any purpose.

In May, 1978, the Den Hartogs conveyed their remaining land, Lot A, to Talbot, and Alexander Parker conveyed Lot C to Talbot, retaining Lot B, on which the Parkers constructed their home. In the deed from Parker to Talbot conveying Lot C, Parker granted Talbot the same easement rights over Lot B, for the benefit of Lot C, that the Den Hartogs had reserved over Lot B for the benefit of Lot A. Thus, Talbot, the new owner of Lots A and C, now possessed rights over a part of the Parkers property for the purpose of ingress and egress by motor vehicle or otherwise, for the benefit of Lots A and C, which is now the Garrison Place property. [Note 38] These deeds utilize the same unrestricted language regarding the scope of the right of way easement. However, in December, 1978, Parker and Talbot entered into the 1978 Maintenance Agreement, which further specified and somewhat altered the parties respective rights and obligations with respect to the right of way easement. Once a dwelling was constructed on the Parkers property, Lot B, the owners of Lot B, and the owners of Lots A and C were to share equally in the cost of repair, maintenance and snow removal on the right of way easement until such time as a road has been constructed and accepted by the town as a public way over the driveway built over the

easement and that part of Lot C where the driveway is located. Until then, Talbot and Parker, their heirs, successors and assigns have the right to use the driveway in common for all purposes for which private driveways are customarily used in the Town of Carlisle. [Note 39] Thus, although future public use, in the form of a future accepted town way, was contemplated, the owners of the dominant and servient estates agreed in a written agreement, recorded at the Registry, that until such acceptance as a public way, the use of the right of way easement was to be limited to use as a private driveway, and that both parties would share equally in the cost of maintenance of the driveway.

The Parkers do not challenge the existence of the right of way easement or its location. Rather, they maintain that the original intent of the parties was to use the driveway for private access to Lots A, B, and C, three the single-family residential lots, until such time as a new road was constructed and accepted by the Town as a public way. Specifically, they point to the language in the 1978 Maintenance Agreement, which they argue supports their position that the right of way easement was explicitly limited to use for private access only. The proposed development and the public trails, the Parkers assert, drastically increase the intensity of the use and overburden the right of way to their detriment as owners of the servient estate on Lot B.

Where the easement arises by grant and not by prescription, and is not limited in its scope by the terms of the grant, it is available for the reasonable uses to which the dominant estate may be devoted. Bedford v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 82 (2004), quoting Parsons v. New York N.H. & H.R.R., 216 Mass. 269 , 273 (1913)). The owner of land burdened by an easement, here the Parkers, retains the right to make all uses of the land that do not unreasonably interfere with exercise of the rights granted by the servitude. Martin v. Simmons Props., LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 8 (2014). However, the party benefitted by an easement, here Brendon Homes, is entitled to make only the uses reasonably necessary for the purpose of the easement. Id. The obligation between those who hold separate or common easements over the same land is that they act reasonably in the exercise of their privileges so as not to interfere unreasonably with the rights of other easement holders. Cannata v. Berkshire Natural Resources Council, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 789 , 797 (2009), citing to Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 4.12 comment b, at 626-627 (2000). This requires a balancing of the interests of the two parties. Shapiro v. Burton, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 327 , 334 (1987). The analysis is to be governed by equitable principles, namely, what is reasonable in the exercise of their respective privileges. Id. The benefits and convenience to both easement holders must be taken into account. Id.

I find that the 1978 Maintenance Agreement was a modification of the terms of the original reservation and grant of the right of way easement in the deeds from the Den Hartogs to Parker and from Parker to Talbot. The 1978 Maintenance Agreement was executed by the owners of the dominant and servient estates subject to the easement, the same parties to the original deeded right of way easement (or their successors-in-interest). Although the 1970 Deed to Parker contained no restrictive language as to the use of the easement, the 1978 Maintenance Agreement did just that. By entering into the 1978 Maintenance Agreement, the Parkers and Brendon Homes predecessor, Talbot, agreed that travel over the right of way easement would be limited to access for all purposes for which private driveways are customarily used in the Town of Carlisle. [Note 40] Essentially, the Maintenance Agreement expressly constrained the parties rights under the easement, requiring thereafter that the right of way only be used for purposes typically associated with a private driveway, and that such limitation continue until a future road is accepted as a public way.

The Parkers argue that the language limiting the use of the right of way easement to the purposes for which private driveways are customarily used in the Town of Carlisle has the effect of (1) limiting access over the easement to no more than three single family homes, given that the Bylaw, in 1978, did not contemplate the use of property in a single-family zoning district for an SROSC special permit senior housing development, and (2) prohibiting the use of the easement for access by the public to the parking area and trails. The Parkers are incorrect in their first contention, but correct in their second contention.

Neither the language of the 1970 Deed to Parker nor the 1978 Maintenance Agreement mentions the term single-family residences or the like. Though SROSC developments were only adopted by the Town in 1995 and did not exist when the easement was created, this does not mean that access over the right of way easement is prohibited for residential uses other than single-family homes. The Parkers presented no evidence that it was customary in Carlisle for such private ways to provide access only to single-family lots, and neither the reservation of easement nor the 1978 Maintenance Agreement incorporated explicitly or implicitly a limitation on uses to those then authorized by the Bylaw.

Even if it was customary for private driveways to only access single-family lots at the time of the Maintenance Agreement, this does not fix the scope of the easement eternally. The scope may change over time, and uses satisfying new needs have been held to be permissible. See Lawless v. Trumbull, 343 Mass. 561 , 563 (1962); Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 173 (1948); Restatement (Third) of Property § 4.8(2) (2000). An easement granted in general terms is not necessarily limited to uses made of the dominant estate at the time of creation of the easement, and the easement is available for all reasonable uses to which the dominant estate may thereafter be devoted. Marden v. Mallard Decoy Club, 361 Mass. 105 , 107 (1972). That an easement may have once served a particular purpose does not forever foreclose it from being altered for use in another manner, particularly where that altered use coincides with the natural progression and normal development of society and those that benefit from the easement. Glen v. Poole, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 293, 295-296 (1981). Easements are unique in that they have the ability to adapt to accommodate shifting needs, so long as the variations in use are not substantial and are consistent with the general pattern formed by the prior use. Lawless, supra, 343 Mass. at 563; Hayes v. Inniss, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 1138 (2013) (once an easement is created, every right necessary for its enjoyment is included by implication). Mere increased use of an easement is not the proper test for overburdening; rather, use of the easement must be in excess of its original scope to support a finding of an overburdening. Wright v. Patriakeas, 18 LCR 453 , 457 (2010).

The progression from single-family residences to a condominium development, such as the SROSC, is a natural one. In 1995 the Town chose to amend the Bylaw to include SROSCs. Section 5.7.1 of the Bylaw provides that the purpose of the SROSC special permit is to encourage residential development which meets the physical, emotional and social needs of senior citizens, and to encourage the preservation of rurality, open space areas and natural settings, and to encourage energy efficient and cost effective residential development. [Note 41] Changing demographics in Carlisle may have spurred this addition to the Bylaw. The SROSC was created to address the need for additional housing for a growing and aging population while at the same time protecting open space. There is already one SROSC development, Malcolm Meadows, which was approved and constructed in the Town. [Note 42]

Although the right of way easement may have initially serviced single-family residences (the Parkers home and Talbots home, which is to be razed as part of the development of Garrison Place), there is nothing in the language of the original easement or the 1978 Maintenance Agreement confining the use of the driveway to use for access to single-family homes. As used for access to the 16-unit SROSC, the driveway will still be a private driveway, used for residential purposes. This is not a substantial variation, and is consistent with the limitation on the use of the easement to uses for which private driveways are used in Carlisle. In the absence of an express limitation that the right of way easement is only to be used for access to single-family residential lots, Brendon Homes, as the owner of property benefitted by the right of way easement, is entitled to use the easement for ingress and egress to Garrison Place. This is not an unreasonable use, it is consistent with the original grant and with the 1978 Maintenance Agreement, and there was no showing that it would overburden the right of way easement.

The Parkers gain more traction with their next argument, which is that the Planning Board exceeded its authority by conditioning the grant of the special permit on allowing the public access to the Garrison Place property over the right of way easement for the purpose of parking and using trails to be established on the open space parcel. Access over a private right of way for public use, regardless of the eventual intensity of the use, is access for a purpose that is different in kind from access for only private purposes by those living at Garrison Place and their invitees. Mrs. Parker expressed concern, which I credit as not speculative, that there is no enforceable mechanism for limiting access to the three vehicles at a time that are accommodated by the parking area, and that despite signage, some members of the public likely will find their way onto the Parkers property.

More importantly, it is to no avail that Brendon Homes argues that the use by the public will be de minimis. Access by the public over the Parkers property to any degree is categorically inconsistent with the limited access agreed to in the 1978 Maintenance Agreement. Regardless whether one vehicle or ten at a time use the easement over the Parkers property, access by the public is of a different character than private access. See Corey v. Rector, No. 14 MISC 483064, 2016 WL 3926501 (Mass. Land Ct. July 18, 2016) (Long, J.) (Planning Board finding that extension of nonconforming use on private wharf would not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood reversed and vacated where public access to the wharf would be required as a result of the extension of the nonconforming use); Goff, supra, No. 15-P-1144, 2016 WL 4268381 (allowing public access over private right of way may constitute a constructive taking or an overburdening of the right of way).

By agreeing in the 1978 Maintenance Agreement to share half the cost of maintaining the right of way easement, Mr. Parker limited his obligation by limiting use of the easement to the customary uses of a private driveway. He did not agree to open up his land to public access and to bear the burden of maintaining and repairing the roadway to facilitate public access. The Planning Board cannot now require the Parkers to bear the burden of public access over their property where they did not accept such access in the private agreements creating and limiting the right of way easement.

[T]he extent of the easement . . . is fixed by the conveyance. Restatement of Property § 482 (1944); Murphy v. Donovan, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 519 , 527 (1976); Pion v. Dwight, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 406 , 412 (1981); Lowell v. Piper, 31 Mass. App. Ct. 225 , 230 (1991). A servient estate cannot be burdened to a greater extent than was contemplated or intended at the time of the grant. Doody v. Spurr, 315 Mass. 129 , 133 (1943). The public use of an easement granted for private uses clearly exceeds the scope of the grant. Broude v. Massachusetts Bay Lines, Inc., No. 265538, 2005 WL 1501885 at *11 (Mass. Land Ct. June 27, 2005) (commercial use of marina intended for private use overburdens easement for use of marina); Hewitt v. Perry, 309 Mass. 100 , 105 (1941) (use of a recreational easement for a commercial business renting boats to the public overburdened the easement); Rogal v. Collinson, 54 Mass. App. Ct. 304 (2002) (upholding a decision by this court that the proposed use of a trail easement for a commercial trail riding business would exceed the scope of and overburden an easement, which had been reserved to pass and repass on foot and horseback).

Accordingly, I find that the Planning Board exceeded its authority by conditioning the grant of the SROSC special permit on a requirement for public access, any amount of which is inconsistent with the access granted pursuant to the right of way easement as limited by the 1978 Maintenance Agreement.

CONCLUSION

The Decision of the Planning Board is annulled, for the reason that conditions nos. 16 19 of the SROSC special permit Decision, and any other part of the Decision or the plans approved by the Decision requiring public parking or public trail access to be reached by access over the right of way easement on the Parkers property, exceeded the Planning Boards authority. Accordingly, the Decision is remanded to the Planning Board for further proceedings consistent with this decision.

Judgment will enter accordingly.

A. Yes. Tr. 2:68.

ALEXANDER PARKER and JOAN PARKER v. DAVID FREEDMAN, MARC LEMERE, NATHAN BROWN, JONATHAN STEVENS, KAREN ANDON, ED ROLFE, PETER GAMBINO, BRIAN LARSON, and TOM LANE, as members and associate members of the TOWN OF CARLISLE PLANNING BOARD, and BRENDON PROPERTIES, LLC, and BRENDON HOMES, INC.

ALEXANDER PARKER and JOAN PARKER v. DAVID FREEDMAN, MARC LEMERE, NATHAN BROWN, JONATHAN STEVENS, KAREN ANDON, ED ROLFE, PETER GAMBINO, BRIAN LARSON, and TOM LANE, as members and associate members of the TOWN OF CARLISLE PLANNING BOARD, and BRENDON PROPERTIES, LLC, and BRENDON HOMES, INC.