Introduction

This case concerns Lot 13 on Definitive Subdivision Plan D (1981) [Note 1] in the Surfside section of Nantucket, [Note 2] owned by plaintiff Howard Nair as trustee of the Okorwaw Land Trust, and has two parts.

The first the subject of Mr. Nairs complaint is the current validity of a 1982 restriction on the minimum size of Lot 13 and any division of that Lot (hereafter, the lot size restriction), [Note 3] and the effectiveness (if any) of an attempted unilateral extension of that restriction by its sole beneficiary, the Nantucket Land Council (the NLC), a private, non-profit organization. Addressing those questions involves a two- part analysis: (1) interpreting the language and attendant circumstances of the lot size restriction to determine if it was, as the NLC contends, a gift for charitable purposes, taking it out of the otherwise-applicable thirty-year time limitation of G.L. c. 184, §23, and then (2) if the restriction was not such a gift (and thus, as written, now expired), determining if the NLC has proved that the restriction should nonetheless be reformed to run in perpetuity. These issues were the subject of trial.

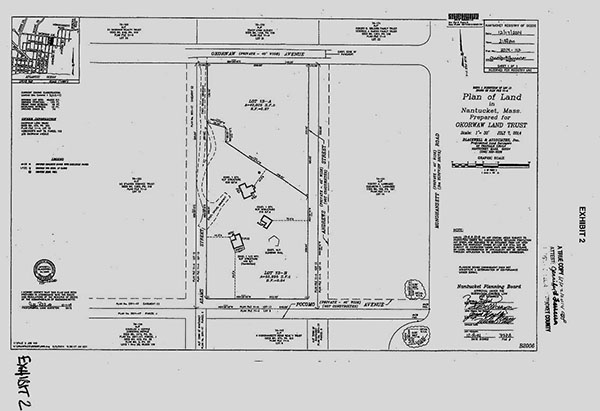

The second part of the case, raised by NLCs counterclaim against Mr. Nair and its third-party complaint against the Nantucket Planning Board, is the NLCs challenge to the boards ANR endorsement of Mr. Nairs plan for dividing Lot 13 into Lots 13-A and 13-B, both of which are less than the size set forth in the lot size restriction (100,000 square feet), but meet the current zoning requirement for minimum lot size (40,000 square feet). See Ex. 2 (ANR plan). [Note 4] Judicial review of ANR endorsements is by certiorari, governed by the provisions of G.L. c. 249, §4. Stefanick v. Planning Bd. of Uxbridge, 39 Mass. App. Ct. 418 , 424 (1995); Murphy v. Plannng Bd. of Hopkinton, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 385 , 389 (2007). [Note 5] Put briefly, the NLC argues that the endorsement should be voided because neither Lot 13-A nor Lot 13-B meet the minimum lot size set forth in the lot size restriction (100,000 square feet), and because it reflects the use of Adams Street as frontage for Lot 13-B in violation of a separate, independent 1982 restriction, which also named the NLC as sole beneficiary, in which the then-owner of Lot 13 (the Surfside Realty Trust), for itself and its successors and assigns, release[d] and covenant[ed] not to assert Adams Street (and certain others) as rights of way (hereafter, the paper streets restriction). These issues were presented for disposition in the context of cross-motions for judgment on the pleadings the proper procedure for

deciding a certiorari case. See Durbin, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 4 & n.5. [Note 6]

The trial aspects of the case were tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial and my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from the entirety of that evidence, I find and rule that, whether or not initially valid (a question I need not and do not reach [Note 7] ), the lot size restriction was not a gift, but rather a bargained-for term, with consideration given, in settlement of litigation between the plaintiffs predecessor-in-title (the Surfside Realty Trust) and the NLC. Over thirty years have now passed, the restriction has expired, and it has not validly been extended. Further, I find and rule that the NLC has failed to prove that the restriction should be reformed to run in perpetuity, and has failed to prove that it should be reformed so that it can be extended unilaterally by the NLC. From the same evidence, I make the same findings and rulings with respect to the paper street restriction.It, too, was not a gift, has thus expired, and this is dispositive of the NLCs challenge to the ANR endorsement of the plan. [Note 8] That challenge also fails on the Record of Proceedings before the Nantucket Planning Board as supplemented by the parties. [Note 9]

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial and, where noted with respect to the ANR challenge, from the Record of Proceedings before the Nantucket Planning Board as supplemented.

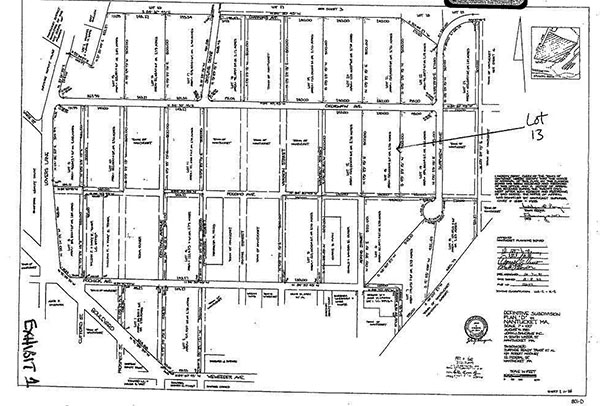

Plaintiff Howard Nair, as trustee of the Okorwaw Trust, is the current owner of Lot 13 on Definitive Subdivision Plan D, approved by the Nantucket Planning Board on October 7, 1981 and recorded at the Registry in February 1982 (Plan D). See Ex. 1. The subdivision is in the Surfside area of Nantucket, and was laid out by the then-owner of that land, the Surfside Realty Trust, working from two prior plans the 1889 Plan of Lands of the Nantucket Surfside Land Co. (May 17, 1889) (the 1889 plan), and the 1972 Plan of Lands, Surfside, Nantucket, Mass. (Sept. 1972) (the 1972 plan).

As shown on Plan D, Lot 13 has 120,000 square feet and is bounded by Okorwaw Avenue on the north, Pocomo Avenue on the south, [Note 10] Lot 14 on the east (the Andrews Street easement shown on both the 1889 plan and the 1972 plan straddles the two lots), and Lot 12 on the west (the Adams Street easement shown on the 1889 plan and the 1972 plan straddles the two lots). See Ex. 1.

Okorwaw Avenue has been constructed and paved.

Pocomo Avenue in this section is currently only a paper street, i.e. a street shown on a plan but not built on the ground. Berg v. Town of Lexington, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 569 , 570 (2007).

The three buildings presently on Lot 13 are accessed by a gravel road in the Adams Street easement, running along the northern two-thirds of the western edge of the Lot. See Ex. 2. [Note 11] The planning board considered this to be a built out section of Adams Street, with the remaining length of Adams Street along the west of Lot 13 still a paper street. See n.6, supra and Ex. 2.

The Andrews Street easement on the east of Lot 13 is a paper street along that entire length. Because it is not necessary for frontage, the status of Andrews Street is irrelevant to this case.

As previously noted, both Okorwaw Avenue and Adams Street were either shown on an approved subdivision plan at the time of the ANR endorsement, [Note 12] were ways in existence in 1955 with sufficient width, suitable grades, and adequate construction to provide for the [needs of] vehicular traffic in relation to the proposed use of the land abutting thereon or served thereby, and for the installation of municipal services to serve such land and the buildings erected or to be erected thereon, or both. See n.6.

Defendant NLC is a private, member-supported, non-profit organization founded in 1974 to promote the protection of the ecology and natural environment of Nantucket.

The Plan D subdivision was created by the Surfside Realty Trust which, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, owned Lot 13, a number of other lots in the Plan D subdivision, a number of lots in the nearby subdivisions it had also created, and other adjoining or nearby land. The NLC and a number of allied landowners asserted title to some of that nearby land (in the Madequecham area, the subject of Land Court Case Nos. 78 MISC. 89960 and 78 MISC. 90275) and, in addition, appealed the approved Plan D and other subdivision plans (the subject of Nantucket Superior Court Case Nos. 1981 Civ. 1886 and 1981 Civ. 1908). [Note 13] Each of those cases was settled, with a dismissal with prejudice filed, in return for various concessions by Surfside. [Note 14] These included two restrictions, both executed on January 15, 1982 and then recorded at the Registry of Deeds on February 26, 1982. [Note 15]

The first of these restrictions (the lot size restriction), as applicable to Lot 13, was as follows:

We, [the trustees of the Surfside Realty Trust],[ [Note 16] ] by power conferred [in the Trust document] thereby and every other power us hereunto enabling, for consideration paid, grant to NANTUCKET LAND COUNCIL, INC., a Massachusetts corporation having an usual place of business in Nantucket, Massachusetts, the restrictive rights hereinafter specified, on the land hereinafter specified, and to that end, the grantors, for themselves and their successors and assigns, hereby specify, provide, covenant with the grantee, and grant as follows:

1. The lands affected by said restrictive rights constitute certain Lots hereinafter specified, situated in the Town and County of Nantucket, and shown on a plan entitled Definitive Subdivision Plan D Nantucket, MA. Dated August 31, 1981, by John J. Shugrue, Inc., recorded or to be recorded with said Registry of Deeds.

2. The rights hereby granted constitute the right to enforce the restrictions, and the grantors hereby covenant, for themselves and their successors and assigns as aforesaid, to stand seized and hold title to said premises, and to convey the same, subject to the restrictions, that:

A. As to [Lot 13] as shown on said plan

or any portion or portions thereof, the same shall not be resubdivided, or combined and resubdivided, in such a manner as to create or leave any lot containing less than 100,000 square feet of land

..

3. The restrictions hereunder shall be binding upon the grantors and their successors and assigns, and may be enforced solely by the grantee [the NLC].

Agreement by and between the Trustees of Surfside Realty Trust and the Nantucket Land Council (Jan. 15, 1982), recorded in Book 189, Page 292 (Feb. 26, 1982).

No term or expiration date was set for the restriction, nor was any provision made for its extension.

The second (the paper streets restriction), as applicable to Lot 13, provided:

SRT [Surfside Realty Trust], for itself and its successors and assigns, hereby releases, and covenants not to assert, subject to and except as hereinafter provided, any rights of way over any of the ways situated in Nantucket and shown on the plan entitled Plan of Land, Surfside, Nantucket, Mass., dated September 1972, by Essex Survey Service, Inc., recorded with said Registry of Deeds in Plan File 3-D,

Excepting:

* * *

D. The ways shown on a plan entitled Definitive Subdivision Plan D, Nantucket, MA, dated August 13, 1981, by John J. Shugrue, Inc., recorded or to be recorded with said Registry of Deeds, as Boulevard, Pochick Avenue and an easterly extension thereof to the easterly side of Lot 5, Lovers Lane, Okorowaw [sic Okorwaw] Avenue, Skyview Drive, Surfview Drive and Webster Street;

* * *

[And] provided, however, that:

F. The release and covenant made hereby shall not apply to or be effective with respect to the land of any person or persons who at any time hereafter asserts or assert, by legal action, act in pais,[ [Note 17] ] or otherwise, any right of way on, over or through any lands shown on said plan recorded in Plan File 3-D, now or hereafter owned by SRT, which right of way is alleged to arise or exist by implication of law from said plan recorded in Plan File 3-D or any other plan recorded prior thereto with the Nantucket Registry of Deeds, and has not been expressly granted by instrument of record to such person or persons; and SRT expressly reserves to itself and its successors and assigns all rights, titles and interests which it now has in and to the land of any and all persons who so assert any such right of way

Agreement by and between the Trustees of Surfside Realty Trust and the Nantucket Land Council (Jan. 15, 1982), recorded in Book 189, Page 289 (Feb. 26, 1982).

No term or expiration date was set for the restriction, nor was any provision made for its extension. Unlike the lot size restriction, the paper streets restriction did not state who had the power to enforce it.

At the time these restrictions were signed, the zoning applicable to Lot 13 required a minimum lot size of 80,000 square feet.

G.L. c. 184, §23, which provides that [c]onditions or restrictions, unlimited as to time, by which the title or use of real property is affected, shall be limited to the term of thirty years after the date of the deed or other instrument or the date of the probate of the will creating them, was in full force and effect when the lot size restriction and the paper streets restriction were negotiated, agreed, signed, and recorded. [Note 18] It has only four exceptions to its thirty-year time limitation, only one of which is at issue in this case the exception for gifts or devises for public, charitable or religious purposes. [Note 19]

The attorney who negotiated the restrictions on behalf of the NLC was unaware that a thirty-year time limitation existed, and the limitation was never mentioned during those negotiations. The attorney negotiating the restrictions on behalf of the Surfside Realty Trust, Edward Mendler, however, was fully aware of the time limitation. I say this, and so find, because he was the author of the Massachusetts Conveyancers Handbook (the real estate volume of the Massachusetts Practice Library treatises), which specifically discusses it. [Note 20] As Attorney Mendlers communications during the course of negotiations indicate, his goal in agreeing to the lot size restriction was to do so

consistently with necessary flexibility for SRTs marketing and also for future residence owners who may wish to adjust boundary lines. Letter from Edward Mendler Jr. to NLC counsel Peter Fenn, Esq. at 1 (Dec. 1, 1981).

A document entitled Notice of Restriction, which the NLC intended to extend the lot size restriction beyond the thirty-year period, was signed by the President and Vice-President of the NLC on January 12, 2012 and recorded thereafter at the Registry. Neither the Surfside Realty Trust nor any of its successor lot owners signed the document. Mr. Nair who neither signed the purported extension, nor was asked to do so purchased Lot 13 in 1988. [Note 21] The NLC has neither a fee interest in any real estate abutting Lot 13, nor a fee interest in any land within the Plan D subdivision.

On March 31, 2012, Article 50 (Zoning Map Change: Surfside) was adopted by the Nantucket Town Meeting. This new zoning by-law changed Lot 13 and others from Limited Use General-2 (LUG-2) to Limited Use General-1 (LUG-1), which decreased the required minimum lot size from 80,000 square feet to 40,000 square feet. Mr. Nairs proposed division of Lot 13 conforms to this re-zoning. See Ex. 2. It does not, however, comply with the lot size restriction. Lot 13-A will have 40,005 square feet. See Ex. 2.

Lot 13-B will have 55,995 square feet. Id. The line dividing the proposed new lots was drawn to ensure that the existing structures on Lot 13-B conformed to current setback requirements. Id.

On December 8, 2014, Mr. Nairs division plan (Ex. 2) was endorsed by the planning board Approval Under the Subdivision Control Law Not Required, indicating that the board found each of the proposed new lots to be of sufficient size to comply with zoning and to have the required frontage. The Record of Proceedings before the planning board contains substantial evidence in support of this finding. See n.6, supra.

Further facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

G.L. c. 184, §23 limits restrictions on the title or use of land, which are unlimited as to time in the instrument itself, to a period of thirty years. Both of the restrictions at issue in this case the lot size restriction and the paper streets restriction have no time limitation in their instruments, and thus fall squarely within the statutes reach. More than thirty years have expired since they were placed on Lot 13. They are thus no longer valid unless they fall within one of §23s exceptions to the thirty-year limitation. [Note 22] They do not.

As previously noted, three of the four exceptions are clearly inapplicable, and the NLC does not argue otherwise. (1) The restrictions did not exist on July 16, 1887. (2) They were not contained in a deed, grant or gift of the Commonwealth. And (3) the provisions of G.L. c. 184, §32, making conservation restrictions held by private charitable organizations unlimited as to time are inapplicable because these restrictions were not approved by the Nantucket Selectmen or town meeting, nor by the pertinent state officials, as §32 requires.

The NLCs argument focuses solely on the fourth exception that these restrictions were a gift or devise for public, charitable or religious purposes. The facts are otherwise.

The basic principle governing the interpretation of deeds [Note 23] is that their meaning, derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007) (quoting Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998)). The language used is the primary source for determination of the parties intent, and where that language is clear and unambiguous the inquiry need go no further. Charlestown Marina, LLC v. Brunner, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 1104 (2016), 2016 WL 454959 at *1 (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28).

A gift is a thing given willingly to someone without payment; a present, Concise Oxford Dictionary 597 (10th ed. 1999); something bestowed voluntarily and without compensation, American Heritage College Dictionary 585 (4th ed. 2002). See also Massachusetts Port Authority v. Basile, 17 LCR 185 , 187 (2009). The plain language of the restrictions neither states nor suggests that they were gifts. To the contrary, the lot size restriction states that it was for consideration paid, and the written settlement agreement (Jan. 14, 1982), which attaches the form and text of both restrictions as exhibits, specifically references the dismissal of the lawsuits in return for those restrictions and the other terms in the agreement. That dismissal was the consideration.

This is confirmed by the attendant circumstances. See Sheftel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. at 179 (surrounding circumstances may be considered in connection with the analysis of the language of an agreement). I listened carefully to the witnesses testimony and read each of the exhibits admitted into evidence, and neither the word gift nor its equivalent was ever used in any of the parties communications, nor appears in their internal documents. Following the settlement, the NLC issued a press release regarding the restrictions and the settlements other terms, and nowhere said that this was done as an act of charity or as a gift. Instead, the press release stated that the settlement ended years of litigation about the ownership of over 160 acres of land in and near Madequecham Valley, as well as the appeals of Planning Board approval of two large subdivision plans in the Surfside area, and specifically references the restrictions and the conservation land conveyance as among the terms obtained. See News Release, NLC and SRT Reach Agreement (undated). The NLCs Notice of Restriction, which purports to extend the duration of the lot size restriction, further demonstrates that even the NLC did not view that restriction as a gift, which would have required no such renewal.

Nothing in any Surfside Realty communication references any gift, and there was no evidence that Surfside ever sought or obtained any charitable deduction.

The NLCs main argument for gift, at least with respect to the lot size restriction, is its contention that Surfside gave up nothing by agreeing to that restriction because it simply reflected the zoning in effect at that time. But that is incorrect. Zoning can change indeed, it did and variances from zoning can always be applied for and, if the criteria are met, can be granted. Even if Surfside itself had no plans for smaller lots, or calculated that it would have sold out its interests before any zoning change was likely, the possibility of future zoning changes had value for the lots. As previously noted, Surfsides goal in agreeing to the lot size restriction was to do so consistently with necessary flexibility for SRTs marketing and also for future residence owners who may wish to adjust boundary lines. Letter from Edward Mendler Jr. to NLC counsel Peter Fenn, Esq. at 1 (Dec. 1, 1981). Giving up, for thirty years, the potential to take advantage of such changes, was certainly sufficient for consideration.

Reformation of the Restrictions

The NLCs final argument that, should the court find the thirty-year time limitation applicable, the restrictions should be reformed to make the restrictions perpetual ones also fails. Reformation cannot change facts. Thus, it cannot make the restrictions a gift. Since, as discussed above, restrictions unlimited as to time have a thirty-year limit unless they fall within one of §23s exceptions [Note 24] (which these do not), presumably the reformation would be to make the restrictions effective for a fixed time, with a provision for their extension (a very significant re-writing). See n.22, supra (noting that this is the only way such a restriction could go beyond thirty years). I need not reach the question of whether such a reformation would legally be possible G.L. c. 184, §27, which governs extendable restrictions in common-scheme-type settings, requires (among other things) the assent of the owners of fifty percent or more of the area in which the subject parcel is located, thus precluding unilateral extensions because, as a factual matter, no grounds for reformation exist. Reformation (an equitable remedy) requires a substantive basis fraud, mistake, accident or illegality. See Beaton

v. Land Court, 367 Mass. 385 , 392 (1975). The NLC relies solely on a theory of mistake. To be a mistake warranting reformation, the mistake must either be mutual or made by one party (unilateral) such that the other party knew or had reason to know of it, and the proof of such mistake must be full, clear, and decisive. Nissan Autos. of Marlborough Inc. v. Glick, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 302 , 306 (2004). As a factual matter, no such mistake has been proven.

I accept, for purposes of argument, that attorney Fenn (who represented the NLC in the negotiations that led to the restrictions) wanted them to be perpetual. But there is no evidence, and certainly none persuasive, that attorney Mendler (who represented Surfside) had the same intent. As previously discussed, Mr. Mendler the author of a definitive treatise which discusses the issue was certainly aware of the thirty-year limitation for restrictions unlimited on their face as to time. [Note 25] He never said or wrote anything different to Mr. Fenn, nor ever referred to the restrictions as perpetual or extendable in any way. The restrictions, and the overall settlement itself, were closely negotiated. As a careful lawyer fully aware of the issues involved, Mr. Mendler would have drafted or edited the restrictions to ensure (or, at least, attempt to ensure) perpetuity if that was truly his intent.

I also find that there was no unilateral mistake known to the other. Attorney Fenn may have intended that the restrictions be perpetual, but he never said so, and there was no proof, and certainly none persuasive (much less full, clear, and decisive), that attorney Mendler knew Mr. Fenn was operating on an understanding that perpetuity had been agreed. The evidence shows that Mr. Mendler was aware of the thirty year limitation and was willing to agree to that time for the restrictions, while retaining full flexibility thereafter. Mr. Mendler had every right to assume that Mr. Fenn, an attorney, was aware of G.L. c.184, §23 (or, at the least, the issues it presented), and to assume that Mr. Fenn would bring them up if he wanted something different than the statutorily- mandated thirty years. There was no evidence to the contrary.

In sum, there are no grounds for reformation of the restrictions. Each was limited to thirty years, which has now expired, and they are thus no longer enforceable.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and declare that the lot size restriction and the paper streets restriction have both expired, and are no longer enforceable against Lot 13. NLCs G.L. c. 249, §4 certiorari challenge to the Nantucket Planning Boards ANR endorsement of Mr. Nairs divison plan (Ex. 2) is DISMISSED, WITH PREJUDICE.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

factual finding since it is supported by substantial evidence in the record. See, e.g., the Nantucket Planning Board Staff Report (Dec. 4, 2014) stating that both roads meet minimum width, grade, and construction requirements; Staff recommends endorsement (Record of Proceedings before Nantucket Planning Board at 8); the un-rebutted statement of Mr. Nair in his application that the roads were in existence in 1955 (Record at 10-11); and the survey plan presented to the board showing both Okorwaw Avenue and Adams Street as existing on the ground (Record at 12) (Ex. 2 is the ANR-endorsed copy of that plan). In any event, the NLC does not contend otherwise. Instead, its challenge is based solely on its contention that the paper street restriction is still valid and applicable. See n.8, infra.

In addition, the restrictions do not come within G.L. c.184, §26 (land use or conservation restrictions) because they do not have the benefit of §32, and because the NLC is not a governmental body. The reasons why G.L. c. 184, §27 does not apply to allow the restrictions to be extended are discussed below. See n.22.

HOWARD NAIR as trustee of the Okorwaw Land Trust v. NANTUCKET LAND COUNCIL, INC. v. BARRY RECTOR, LINDA WILLIAMS, JOSEPH MCLAUGHLIN and NATHANIEL LOWELL as members of the Planning Board of the Town of Nantucket.

HOWARD NAIR as trustee of the Okorwaw Land Trust v. NANTUCKET LAND COUNCIL, INC. v. BARRY RECTOR, LINDA WILLIAMS, JOSEPH MCLAUGHLIN and NATHANIEL LOWELL as members of the Planning Board of the Town of Nantucket.