Introduction

John and Martha Shaw own two adjoining lots in Cohasset, which neither individually nor together satisfy the minimum lot size requirement of 60,000 square feet. The Shaws obtained a building permit to build a house on one of the lots under a provision of the Cohasset Zoning Bylaw that allows construction on prior nonconforming lots notwithstanding their being held in common ownership, under certain conditions. Plaintiffs Alexander Kaines and Stephen Crummey, appealed the building permit to the Cohasset Zoning Board of Appeals (Board), which upheld the building permit, and have appealed that decision to this court. At issue in the parties' cross-motions for summary judgment before the court is whether the common-law merger doctrine, as codified in G.L. c. 40A, § 6, applies to the Shaws' property, or whether the relevant provision of the Cohasset Zoning Bylaw has abrogated the merger doctrine. As set forth below, because Cohasset has abrogated the merger doctrine and the Shaws meet the requirements of the relevant bylaw provisions, the building permit was properly issued. The Board's decision will be affirmed, Kaines' and Crummey's amended complaint dismissed with prejudice, and the Shaws' counterclaim dismissed without prejudice. Because it is not entirely clear where all this leaves the parties' companion case, a telephone status conference will be set down to determine the next steps in that action.

Procedural History

On or about July 31, 2014, the defendants, John and Martha Shaw (Shaws), were granted a permit to construct a single family home on their property. The plaintiffs, Alexander Kaines (Kaines) and Stephen J. Crummey (Crummey), appealed the issuance of the building permit to the Board. The Board upheld the issuance of the building permit in a Decision dated December 1, 2014. On the evening of December 1, 2014, the Board also met in executive session with Cohasset's Town Counsel. In response to that executive session, Koines and Crummey filed an Open Meeting Law complaint with the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and filed a Notice and Claim of Constructive Approval pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 15. On December 24, 2014, Koines and Crummey filed a complaint in this Court appealing the Board's decision to uphold the permit and only naming members of the Board as defendants, an action docketed as case no. 14 MISC 489038 (2014 Action).

On January 7, 2015, the Shaws filed a complaint against Koines, Crummey, and the Board in a separate, but related matter regarding Koines and Crummey's Open Meeting Law complaint and the Notice and Claim of Constructive Approval, an action docketed as case no. 15 MISC 000007 (2015 Action). On January 15, 2015, the Board filed a Motion to Dismiss the Complaint in the 2014 Action for failure to name an indispensable party, the Shaws. A case management conference was held on March 3, 2015, where the Court decided that the 2014 and 2015 Actions should be treated as companion cases, with proceedings in the 2015 Action stayed pending a decision by the Attorney General on the Open Meeting Law complaint. The Court allowed the Board's Motion to Dismiss, ordering the plaintiffs to file an amended complaint. On March 9, 2015, Koines and Crummey filed an Amended Complaint naming the Shaws as defendants along with the Board.

On April 1, 2015, the Shaws filed Defendants' Counterclaim and Third-Party Complaint Under M.G.L. c.240, §14A in the 2014 Action, naming Crummey as the defendant and the Town of Cohasset (Town) as a third party defendant (Counterclaim). The Town filed their Answer to the Defendants' Third-Party Complaint on April 13, 2015. The Shaws filed the Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment (Shaws' Summary Judgment Motion), Memorandum in Support of Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, Defendants' Concise Statement of Material Facts in Support Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, and the Appendix of Materials Supporting Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, including the Affidavit of Kate Moran Carter, Esq. in support of Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment on May 15, 2015. Also on May 15, 2015, Crummey filed the Third Party Defendants' Motion to Dismiss the Shaws' Counterclaim (Crummey's Motion to Dismiss). On May 22, 2015, the Office of the Attorney General responded to Koines and Crummey's Open Meeting Law complaint, finding that while the Board's December 1, 2014 executive session was not sufficiently specific, "the Board did not violate the Open Meeting Law. No further action was taken following the Attorney General's response.

On June 12, 2015, the Town and the Board filed their Motion for Summary Judgment and Dismissal of the Amended Complaint, Memorandum in Support of Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, and Responses to the Concise Statement of Material Facts filed by the Shaws in Support of Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment. On June 15, 2015, Koines and Crummey filed Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment as well as a Cross Motion for Summary Judgment (Koines' and Crummey's Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment), Responses to Defendants' Concise Statement of Material Facts in Support of Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, Plaintiffs' Statement of Additional Material Facts in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment, and the Appendix to Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment including the Affidavits of Crummey and Koines. Also on June 15, 2015, the Shaws filed Defendants' Opposition to Crummey's Motion to Dismiss Counterclaim and the Affidavit of Kate Moran Carter, Esq. in Support of the Defendants' Opposition to Crummey's Motion to Dismiss Counterclaim. On June 25, 2015, the parties filed their Combined Concise Statement of Material Facts. The Summary Judgment Motions and Third Party Defendants' Motion to Dismiss Counterclaim were heard on June 30, 2015, and taken under advisement. On August 4, 2015, Koines and Crummey waived and withdrew their Notice and Claim of Constructive Approval in the 2015 Action.

This Memorandum and Order follows.

Summary Judgment Standard

Generally, summary judgment may be entered if the "pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter oflaw." Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court is to draw "all logically permissible inferences" from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991). "Summary judgment is appropriate when, 'viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law."' Regis Coll. v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012), quoting Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991).

Undisputed Facts

The following facts are undisputed.

1. Defendants/Third-Party Plaintiffs, the Shaws, own the property at 390 Atlantic Avenue, Cohasset, Massachusetts (Shaw Property). John A. Shaw's and Martha G.W. Shaw's Concise Statement of Material Facts with Responses of Plaintiffs Stephen Crummey and Alex Koines and Plaintiffs' Statement of Additional Facts ¶ 2 (hereinafter Defendants' Statement of Material Facts).

2. Plaintiff/Third Party Defendant Crummey and his wife own the property at 394 Atlantic Avenue, Cohasset, Massachusetts (Crummey Property). Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 1.

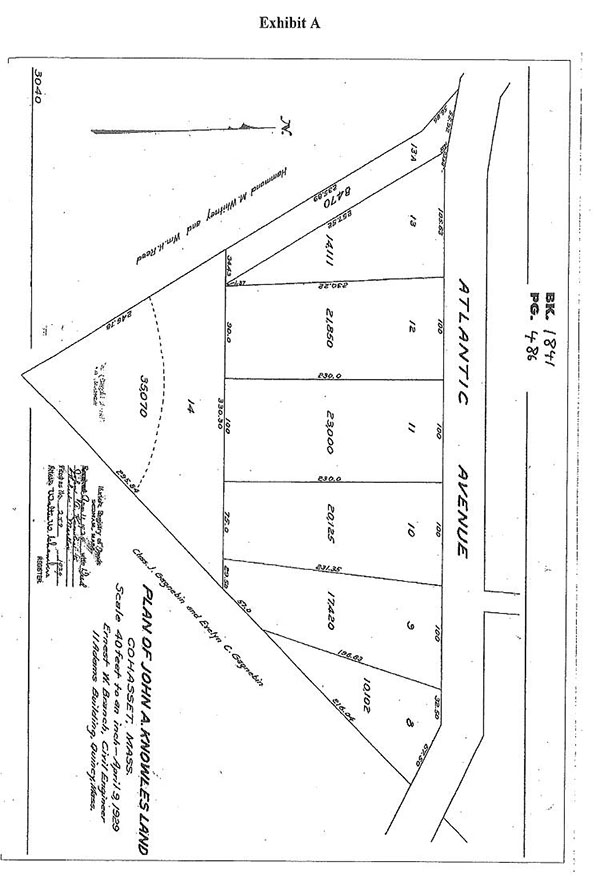

3. The Shaw and Crummey Properties were originally a single parcel of land held in common ownership (along with several other adjoining lots) by John Appleton Knowles (Knowles). On April 11, 1929, Knowles conveyed those parcels to Robert Martin (Martin) by a deed recorded with the Norfolk Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 1841, Page 486 (1929 Knowles deed). Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 3; Appendix of Materials Support John A. Shaw's and Martha G.W. Shaw's Motion for Summary Judgment Exhibit 2 (hereinafter App. Exh. _ ).

4. The surveyed properties are shown on a plan (the 1929 Knowles Plan), attached as Exhibit A. Knowles conveyed a triangular parcel of land to Martin comprised of Lots 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 13A, and 14 as shown on the 1929 Knowles Plan. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 4; App. Exh. 3.

5. At the time the 1929 Knowles Plan was recorded, there were no zoning bylaws in Cohasset. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 14.

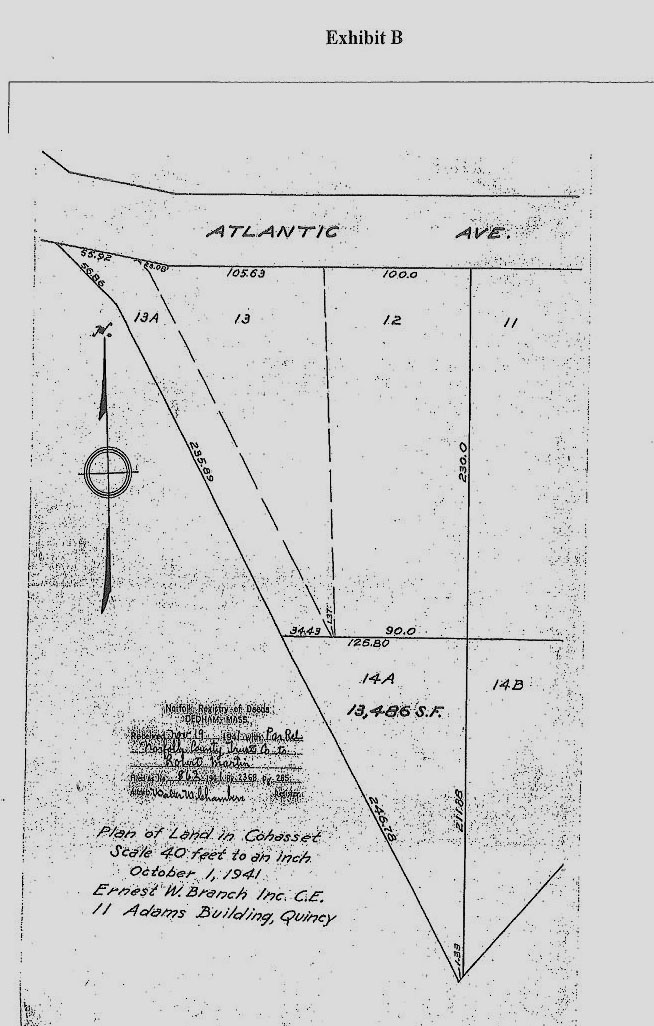

6. In 1941, Martin further divided Lot 14 into Lots 14A and 14B, shown on a "Plan of Land in Cohasset" dated October 1, 1941 and recorded in the registry in Book 2368, Page 285 (the 1941 Martin Plan), attached as Exhibit B. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 5; App. Exh. 1.

7. Lot 12 and Lot 14A, as shown on the 1941 Martin Plan, comprise the now Shaw Property. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 2; App. Exh. 1.

8. Lots 13 and 13A, as shown on the 1941 Martin Plan, comprise the now Crummey Property. Crummey is the westerly abutter to the Shaw Property. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 1; App. Exh. 1.

9. In 1939, Martin conveyed Lots 12, 13, and 13A to Bartlett Tyler and Ruth L. Tyler (Tylers) and in 1941, after dividing Lot 14 into lots 14A and 14B, conveyed Lot 14A to the Tylers as well. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶¶ 6, 7; App. Exh. 4, 5.

10. In 1983, Ruth L. Tyler conveyed the four lots (Lots 12, 13, 13A, and 14A on the 1941 Martin Plan that now make up the Shaw and Crummey Properties) to Robert Najar (Najar) by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 6172, Page 97. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 8; App. Exh. 6.

11. These four lots continued to remain in common ownership through several zoning changes, including the zoning change of 1985, which increased lot area in a Residential C (R-C) zoning district to 60,000 square feet. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶¶ 19, 20; App. Exh. 15.

12. In 1990, Robert Najar conveyed the four lots to Francois L. Nivaud and Annick D. Nivaud (Nivauds), by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 8576, Page 513. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 9; App. Exh. 7.

13. In 2002, the four lots fell out of common ownership when the Nivauds conveyed Lots 13 and 13A (the now Crummey Property) to Mark C. Healy (Healy) and his wife by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 17571, Page 500. Defendants' Statement of Material

Facts ¶ 10; App. Exh. 8.

14. In 2007, the four lots once again came under common control when the Nivauds conveyed Lots 12 and 14A (the now Shaw Property) to Healy, as Trustee of The Healy Realty Trust, by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 25374, Page 298. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 12; App. Exh. 10.

15. The two properties were separated once more on September 12, 2013, when Healy conveyed Lots 13 and 13A to the Crummeys by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 31751, Page 432. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 11; App. Exh. 9.

16. On August 6, 2014, the Healy Realty Trust conveyed Lots 12 and 14A to the Shaws by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 32466, Page 254. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 13; App. Exh. 11.

17. At the time of the conveyance to the Shaws, Lot 12 was unimproved, vacant land. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 27; App. Exh. 13.

18. The Shaw Property and Crummey Property are located in an R-C zoning district in Cohasset. Both properties have less than 60,000 square feet- the necessary minimum lot area for single-family lots in an R-C district under the 1985 Bylaw. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶¶ 17, 19; App. Exh. 12, 13, 14.

19. On the Shaw Property, Lot 12 is approximately 21,850 square feet and Lot 14A is approximately 13,486 square feet, with a combined lot area of approximately 35,336 square feet. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶¶ 23, 24; App. Exh. 1, 3.

20. On the Crummey Property, Lot 13 is approximately 14,111 square feet and Lot 13A is approximately 8,470 square feet, with a combined lot area of approximately 22,581 square feet. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶¶ 21, 22; App. Exh. 3.

21. On July 31, 2014, the Town of Cohasset Building Department issued building permit number 14-224 (the Building Permit) to the Shaws to construct a new, single-family dwelling on Lot 12 of the Shaw Property. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 26; App. Exh. 16.

22. On August 27, 2014, Crummey, along with the easterly abutter to the Shaw Property, Koines-who owns property with his wife at 380 Atlantic Avenue (Koines Property) comprised of Lots 11 and 14B as shown on the 1941 Martin Plan-appealed the Building Permit to the Board. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 28; App. Exh. 17.

23. In their appeal, Koines and Crummey argued in relevant part:

... the Building Permit was issued in error. Particularly, the Building Permit should not have been issued because the [Shaw] Property does not comply with the dimensional requirements of the Cohasset Zoning Bylaws. Such nonconformities include a lack of compliance with area requirements for lots within the R-C District, as most recently revised in 1985. While the Property at one time was entitled to grandfathering protection under §8-3 of the Zoning Bylaws, such protections were eliminated in 2007 when the [Shaw] Property was brought into common ownership with adjoining property. As a consequence, pursuant to the local Zoning Bylaws and the doctrine of merger, the Property lost its grandfathering protection.

App. Exh. 17.

24. Section 8.3 of the Cohasset Zoning Bylaw (Bylaw) authorizes the construction of a one-family dwelling or other lawful building on a nonconforming lot under three circumstances, and states in relevant part:

Notwithstanding the lot regulations hereof, a detached one-family dwelling or other lawful building may be constructed on a lot having less than the required area, width, depth, and/or frontage (provided that all other provisions of this bylaw are complied with) if:

1) Such lot is exempted from such requirements by Chapter 40A, Section 6, of the General Laws of the Commonwealth; or,

2) Such lot, on or before the effective date of the requirements in question:

a. Was lawfully laid out by plan or deed duly recorded in the Norfolk Registry of Deeds, or registered in the Registry District of the Land Court;

b. Was in conformity with the area, width, and frontage provisions of the zoning bylaw, if any, applicable to the construction of such a dwelling or other building on said lot at the time of such registration or recording; and,

c. Was, on said effective date, held in ownership separate from that of adjoining land, or if held in ownership the same as that of adjoining land, had an area of not less than: a. 9,000 square feet in R-A district; b. 15,000 square feet in R-B district; c. 20,000 square feet in R-C district; or,

3) Such lot was shown on a definitive subdivision plan duly approved by the Cohasset Planning Board and was in conformity with the area, width, and frontage provisions of the zoning bylaw applicable at the time of such approval to the construction of such a dwelling or other building on said lot.

App. Exh. 12.

25. On December 10, 2014, the Board filed its Decision (the Decision) upholding the Building Department's issuance of the Building Permit pursuant to § 8.3 of the Bylaw. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶¶ 30, 31; App. Exh. 18.

26. The Decision found that Lot 12 is a buildable lot retaining its grandfathered status pursuant to § 8.3 of the Bylaw and the Building Permit was properly granted to the Shaws. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 31; App. Exh. 18.

27. Koines and Crummey appealed the Board's Decision, filing a Complaint with the Land Court on December 24, 2014. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts ¶ 32; App. Exh. 19.

Discussion

The question in this case is whether the Board properly upheld the issuance of the Building Permit to construct a single family home on Lot 12 of the Shaw Property. Koines and Crummey argue that Board's Decision should be annulled because, under the common law "merger doctrine," the Shaw Property and Crummey Property merged in 2007 when Healy retained control of both properties, resulting in the loss of Lot 12's grandfathered status. The merger doctrine provides that undersized adjoining lots that later come into common ownership after the effective date of the bylaw that rendered them nonconforming "merge" for the purposes of achieving dimensional compliance with the current zoning law. Sorenti v. Bd. of Appeals of Wellesley, 345 Mass. 348 , 353 (1963). Essentially, the doctrine calls for adjoining land to be added to the nonconforming lot in order to bring it into conformity or reduce the nonconformity. Preston v. Hull , 51 Mass. App. Ct. 236 , 238 (2001). The Shaws contend that Lot 12 did not lose its grandfathered status because § 8.3 of the Bylaw provides perpetual grandfathering for such commonly owned lots that abrogates the merger doctrine.

The Shaws have also brought a Counterclaim and Third-Party Complaint under G.L. c.240, § 14A, asserting that if the court concludes that the two properties were merged then the Crummey Property also has non-buildable lots. The Shaws argue that "[t]he consequence of such merger and re-division would mean that any external changes to the single-family house located on the Crummey Property after the lot re-division would require a variance from the Bylaw." The cross-motions for summary judgment, therefore, tum on the question of whether the merger doctrine applies or whether § 8.3 abrogates the merger doctrine in Cohasset.

In an action brought pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17, challenging the issuance of a building permit, the "court shall hear all evidence pertinent to the authority of the board . . . and determine the facts, and, upon the facts as so determined, annul such decision if found to exceed the authority of the board . . . or make such other decree as justice and equity may require." Id. This review is described as "a 'peculiar' combination of de novo and deferential analyses." Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N Y, Inc. v. Board of Appeal of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381 (2009), quoting Pendergast v. Bd. of Appeals of Barnstable, 33l Mass. 555, 558 (1954). The court is obligated to hear and find facts in the action de novo; that is, without giving weight to the facts found by the board, but rather assessing evidence presented by the parties. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership v. Board of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 474 (2012); Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N Y, Inc., 454 Mass. at 381 (no evidentiary weight given to board's actual findings). Applying those fact, the court must give deference to the board's legal conclusions and interpretation of its own zoning ordinance, and determine whether it has applied the ordinance in an unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary manner. Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership, 461 Mass. at 474-475; Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N Y, Inc., 454 Mass. at 381-382; Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 487 (1999). A court should overturn a zoning board's decision only if "no rational view of the facts the court has found supports the board's conclusion." Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership, 461 Mass. at 475. "In the end, the court must affirm the board's decision unless it finds [the decision] was 'based on a legally untenable ground."' Britton v. Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 72 (2003), quoting MacGibbon v. Bd. of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 639 (1970).

A zoning by-law's terms "should be interpreted in the context of the by-law as a whole and, to the extent consistent with common sense and practicality, they should be given their ordinary meaning." Hall v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Edgartown, 28 Mass. App. Ct. 249 , 254 (1990); see Rando v. Bd. of Appeals of Bedford, 348 Mass. 296 , 297-98 (1965). "A zoning bylaw must be read in its complete context and be given a sensible meaning within that context." Dalbec v. Westport Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 16 LCR 672 , 674 (2008) citing Selectmen of Hatfield v. Garvey, 362 Mass. 821 , 826 (1973). The court must also look to the intent of the local legislative body, which is controlling, and construe the bylaw's provisions to effectuate the municipality's intent in adopting the bylaw. King v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 30 Mass. App. Ct. 938 , 940 (1991); Southern New England Conference Ass'n of Seventh-Day Adventists v. Burlington, 21 Mass. App. Ct. 701 , 709 (1986); Fin. Corp. v. State Tax Comm'n., 367 Mass. 360 , 364 (1975) (stating that a court must construe a bylaw "in connection with the cause of its enactment, the mischief or imperfection to be remedied and the main object to be accomplished, to the end that the purpose of its framers may be effectuated").

The intent of a bylaw is determined by analyzing the terms, provisions, and subject matter to which it relates. Where the language of the zoning bylaw is clear and unambiguous, no further interpretation is necessary. Murray v. Bd. of Appeals of Barnstable, 22 Mass. App. Ct. 473 , 478 (1986); Massachusetts Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Comm'r of Corps. & Tax'n, 363 Mass. 685 , 690 (1973); Massachusetts Broken Stone Co. v. Weston, 430 Mass. 637 , 640 (2000). Nevertheless, "[i]t is a well-established canon of statutory construction that a strictly literal reading of a statute should not be adopted if the result will be to thwart or hamper the accomplishment of the statute's obvious purpose, and if another construction which would avoid this undesirable result is possible." Watros v. Greater Lynn Mental Health & Retardation Ass'n, 421 Mass. 106 , 113 (1995). "Bylaws should be interpreted in a way that avoids rendering other portions of the bylaw meaningless." Dalbec, 16 LCR at 674 quoting Trustees of Tufts College v. Medford, 415 Mass. 753 , 761 (1993); Adamowicz v. Ipswich, 395 Mass. 757 , 760 (1985).

Koines and Crummey argue that § 8.3 of the Bylaw does not provide immunity from the doctrine of merger of commonly held lots. The Shaws assert that § 8.3 abrogates the common law merger doctrine and grants perpetual protections to lots even if held in ownership the same as adjoining land, as long as the lots meet certain minimum lot area and frontage requirements. Applying these principles of interpretation, the Court agrees with the Shaws.

General Law c. 40A, § 6 states in relevant part:

Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to a lot for single and two-family residential use which at the time of recording or endorsement, whichever occurs sooner was not held in common ownership with any adjoining land, conformed to then existing requirements and had less than the proposed requirement but at least five thousand square feet of area and fifty feet of frontage. Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirement of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply for a period of five years from its effective date or for five years after January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, whichever is later, to a lot for single and two family residential use, provided the plan for such lot was recorded or endorsed and such lot was held in common ownership with any adjoining land and conformed to the existing zoning requirements as of January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, and has less area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirements than the newly effective zoning requirements but contained at least seven thousand five hundred square feet of area and seventy-five feet of frontage, and provided that said five year period does not commence prior to January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six.

(Emphasis added). Section 6 provides grandfather protection for lots held separately at the time of the adoption of the bylaw that renders such lots nonconforming, while providing lots held in common five years of grandfathering protection after the effective date of a zoning change, provided they have a lot size of at least 7,500 square feet. Lot 12 conformed to zoning requirements when the 1985 Bylaw was adopted. The 1985 Bylaw's 60,000 square feet minimum lot size rendered Lot 12, which is 21,850 square feet, nonconforming. However, Lot 12 does not qualify for protected status under § 6 because the Shaw Property was held in common control with the adjacent Crummey Property when the 1985 Bylaw was adopted that rendered the lots nonconforming, and the five year period of protection for lots held in common has lapsed. Based solely on the provisions of G.L. c.40A, § 6, the merger doctrine would appear to apply to the Shaw Property.

Section 6 is not the end of the grandfathering analysis. The second prong of § 8.3 of the Bylaw provides another avenue for grandfathering protection that is not covered by Section 6. Pursuant to § 8.3.2, a lot is considered buildable today if on or before the effective date of the zoning change it was lawfully laid out by plan or deed that was recorded, was in conformity with provisions of the zoning bylaw at the time of such recording, and if held in common ownership with adjoining land, complied with a minimum lot area requirement that varies depending on the particular zoning district where the lot is located. Under § 8.3.2, Cohasset affords protection to nonconforming lots that is not available in § 6. Where perpetual grandfathering, under § 6 is only available to lots held separately at the effective date of the bylaw, § 8.3.2 gives perpetual protection for lots regardless of ownership status, as long as minimum area requirements are met for lots held in common. In effect, § 8.3.2 abrogates the common law merger doctrine.

The Shaw Property is comprised of two lots, Lot 12 and Lot 14A, both located in the R-C zoning district. The lot at issue, Lot 12, is 21,850 square feet. It was created in 1929 and properly recorded in the registry. At the time of the recording, there were no existing zoning bylaws in Cohasset. Thus, Lot 12 was in conformity with the area, width, and frontage provisions applicable to the construction of a building at that time. As of 1985, the effective date when the Bylaw was changed to increase the minimum lot area to 60,000 square feet, Lot 12 was held in common ownership with Lots 13, 13A, and 14, and it had an area in excess of 20,000 square feet, the minimum lot size to qualify for protection for lots in the R-C district under § 8.3.2. Lot 12 satisfies all the requirements for grandfather status set forth in § 8.3.2 of the Bylaw.

The issue, therefore, is not whether Lot 12 meets the requirements of § 8.3.2. It does. The issue is whether § 8.3.2 abrogates the common law merger doctrine as set forth in § 6. Section 8.3.2 of the Bylaw and other "[p]rovisions of this type are obviously intended to avoid the application of the general principle that adjacent lots in common ownership will normally be treated as a single lot for zoning purposes so as to minimize nonconformities with the dimensional requirements of the zoning bylaw or ordinance." Seltzer v. Bd. of Appeals of Orleans, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 521 , 522 (1987); see Vetter v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Attleboro, 330 Mass. 628 , 630-631 (1953); Sorenti, 345 Mass. at 353; Lindsay v. Bd. of Appeals of Milton, 362 Mass. 126 , 131-132 (1972).

Courts have long recognized the ability of a municipality to grant broader protection for owners of nonconforming lots beyond the protections offered in G.L. c. 40A, § 6. "Many cases establish the full prerogative of municipalities to legislate in a manner which gives far greater indulgence to the ability to build upon lots no longer dimensionally compliant with current zoning rules. And one of the indulgences a municipality properly may extend is the lifting of section six's requirement that adjoining commonly-owned lots be merged." Dalbec, 16 LCR at 678; Carabetta v. Board of Appeals of Truro, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 266 , 269 (2008); Luttinger v. Truro Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 11 LCR 72 , 75 (2003) ("When a municipality elects to give local by-law protection without the merger requirement of Section 6, that extra indulgence has been upheld by the court."). "Section 6 provides only a floor and . . . a municipality is free to grant more liberal treatment to the owner of a nonconforming lot." Mohr v. Stroh, 21 LCR 249 , 250-51 (2013) quoting DeSalvo v. Chatis, 1991 WL 11259380, at *3 (Land Ct. Sept. 11, 1991).

The majority of cases compelling owners of adjoining substandard lots to merge are decided under § 6, which only protects residential lots not held in common ownership. Luttinger, 11 LCR at 75 (stating that "many of the by-law provisions treated in the case law are regurgitative of the provisions of § 6, including its exclusion from protected status of lots held in common ownership"); see, e.g., Preston, 51 Mass. App. Ct. at 237-238 (applying § 6 without reference to the Town of Hull's bylaw). In those cases, the municipality had not enacted a more liberal grandfathering provision in its bylaws, such as Cohasset has. See, e.g., Mauri v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newton, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 336 , 339 n.4, 342 (2012) (where the Town of Newton's bylaw provided less grandfathering protection for lots held in common, requiring that the lot be improved with a dwelling to qualify for exemption from merger); Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 902 , 903 (2005) (finding that the Stoughton bylaw "substantially repeats the grandfathering language of a predecessor version of G.L. c. 40A, § 6."); Rice v. Quirk, 20 LCR 450 , 452, n. 3 (2012) (where the provisions of the Town of Sudbury bylaw were substantially identical to § 6). These cases, however, do not change the longstanding principle that towns and municipalities may do away with the merger rule by providing generous exemptions for nonconforming lots held in common ownership. Dalbec, 16 LCR at 678, citing Luttinger, 11 LCR at 75.

The remaining question is whether § 8.3.2 does in fact abrogate the § 6 merger rule. Koines and Crummey argue that it does not because nothing in the Bylaw "provides a clear expression that such lots would be immune from merger in the event of a later combination with another adjoining lot." See Plaintiffs' Amended Complaint Exh. C. While they are correct, this does not end the inquiry. A zoning bylaw does not have to state explicitly that it abrogates the merger doctrine; it may implicitly abrogate the merger doctrine by its terms. Dalbec, 16 LCR at 678; see Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 298 (2008) (finding that there was no language in the bylaw that explicitly or implicitly nullified the merger doctrine).

In Dalbec, for example, the court reviewed the Town of Westport's bylaw to determine whether lots held in common ownership as of the date of the amended grandfathering provision had in fact merged. Dalbec, 16 LCR at 673. The Land Court found that the Town had expressed a clear intent to abrogate the common law merger doctrine by extending grandfathering protections to lots that met a minimum lot area and frontage requirement at the effective date, regardless of ownership structure. In reaching the decision, the Court stated that "[a] municipal grandfather provision can be clear enough to exempt nonconforming lots without directly mentioning and negating the requirement for merger of commonly owned lots." Id.

In Luttinger, the courts reviewed the Town of Truro's bylaw to determine whether abrogation of the merger doctrine was implicit in the bylaw's language. Luttinger, l l LCR at 74-75. The key provisions of the Truro bylaw are analogous to those in § 8.3.2 of the Cohasset Bylaw, providing grandfathering protection to a nonconforming lot if it was: (1) shown on a subdivision plan or described by a deed recorded in the registry prior to the effective date of the bylaw amendment, (2) the lot met certain minimal dimensional requirements, and (3) there was no requirement that the land be held separately from adjoining land at the effective date. Id. at 74. The court held that the Truro bylaw implicitly rejected the merger doctrine by choosing not to distinguish between lots held separately from those held in common. Id. (finding that the bylaw "provides notably greater protection than § 6 in several respects. Most significantly here, the local grandfathering provision is, unlike § 6, devoid of any language requiring the protected land to be held apart from other land."); see Carabetta, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 269-270 (acknowledging that the same bylaw could implicitly reject the merger doctrine).

In Lahti v. Shutzer, 5 LCR 1 (1997), the Land Court found that the subject property had not merged with a commonly owned adjacent property because the Town of Swampscott's bylaw had expressed "a clear intention to provide grandfather protection" for nonconforming lots held separately or in common ownership although the bylaw made no mention of the merger doctrine or common ownership. Id. at 2, quoting Bloch v. Town of Swampscott, 4 LCR 18 , 20 (1996) (concluding that "[t]he protection Swampscott has chosen to afford to certain undersized lots . . . is more generous than the protection that is required by G.L. c. 40A, but it is within its right to be more lenient"); see Shea v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Douglas, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 1114 , 1114-1115 (2008) (finding that the Town of Douglas implicitly intended to extend grandfather protection to commonly owned adjoining nonconforming lots when the bylaw did not state whether the lots had to be held separately).

Like the bylaws in Dalbec, Luttinger, and Lahti, § 8.3.2 does not distinguish between nonconforming lots held separately or in common. It grants perpetual grandfathering regardless of the ownership structure, requiring only that lots held in common at the effective date of the Bylaw meet certain area requirements.

Koines and Crummey argue that an inquiry must be made into the ownership status in the intervening period between the effective date of the bylaw and today. This argument is at odds with § 8.3.2's language, established principles of statutory interpretation, and decisions supporting such interpretations. Section 8.3 begins by stating that "a detached one-family dwelling or other lawful building may be constructed" if certain requirements were previously satisfied. Then, § 8.3.2 specifies the relevant time when those requirements must have been met-"on or before the effective date of the requirements in question." Therefore, in assessing whether a commonly held lot qualifies as a buildable lot under § 8.3.2, only two time periods are relevant: the present and the date of the Bylaw change. Other courts have agreed with this interpretation.

In Seltzer, the court held that the plain language of the grandfathering provision indicated only two relevant time periods, the present and the effective date, and a "purely sequential analysis would defeat the liberal purpose of the provision, which, by incorporation, reaches back to, and speaks as of, a time when the zoning by-law contained no substantial impediment to building an additional house." Seltzer, 24 Mass. App. Ct. at 524. Likewise, in Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 (2003), the court found it illogical to read into the statute additional requirements of ownership status throughout the many intervening years between the effective date and the present instead of solely looking to the effective date of the zoning change. Id. at 260-261 (stating that "as the Land Court judge correctly pointed out, interpreting § 6 to require that lots remain in common ownership to retain grandfather protection would prevent owners from conveying buildable lots, forcing owners instead either to develop the lots themselves or to sacrifice grandfather protection. Such a restriction would do nothing to further the primary purposes of zoning laws, preventing particular uses of land, not uses of land by particular individuals"). Nothing in § 8.3.2 of the Bylaw requires any analysis of Lot 12 during any period in time other than the effective date of the zoning change-1985-and today.

In short, § 8.3.2 implicitly abrogates the common law merger doctrine and provides for grandfather protection of a nonconforming lot held in common with other lots under certain conditions. Lot 12 meets those conditions. It is a buildable lot today, continuing to retain its grandfathered status.

Because the plain language and unambiguous meaning of § 8.3.2 of the Bylaw abrogates the common law merger doctrine, the Court need not reach the issues presented in the Shaws' Counterclaim. Based on the foregoing, the Board had a lawful basis under the Bylaw for upholding the Building Inspector's issuance of the Building Permit. The Decision must be affirmed. In their Counterclaim, the Shaws allege that if the court were to find that the merger doctrine applies to the Shaw Property, it must also apply to the Crummey Property, and seek a declaration to that effect under G.L. c. 240, § 14A. Because the court has found that § 8.3.2 abrogates the merger doctrine, the Shaws are not entitled to that declaration. Crummey's Motion to Dismiss will be allowed. The Counterclaim will be dismissed, although the dismissal will be without prejudice, as issues relating to the Crummey Property, if any, have not been fully addressed on this record.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Shaws' Summary Judgment Motion is ALLOWED, and Koines' and Crummey's Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. Crummey's Motion to Dismiss is ALLOWED. Judgment shall enter in the 2014 Action affirming the Decision, dismissing the Amended Complaint with prejudice, and dismissing the Counterclaim without prejudice.

The status of the claims in the 2015 Action is not entirely clear. Koines and Crummey waived their Notice and Claim of Constructive Approval, and no further action was taken following the Attorney General's response on the Open Meeting Law complaint. What claims remain in the 2015 Action, and what this Memorandum and Order means for those claims, cannot be determined at this time. A telephone status conference in the 2015 Action is set down for April 7, 2016 at 9:30 am, at which the parties shall discuss the appropriate next steps in that action.

SO ORDERED

ALEXANDER C. KOINES and STEPHEN J. CRUMMEY, v. S. WOODWORTH CHITTICK, CHARLES HIGGINSON, DAVID MCMORRIS, BENJAMIN H. LACEY, and JENNIFER R. SCHULTZ, as they are the members of THE COHASSET ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, and JOHN A. SHAW and MARTHA G. W. SHAW.

ALEXANDER C. KOINES and STEPHEN J. CRUMMEY, v. S. WOODWORTH CHITTICK, CHARLES HIGGINSON, DAVID MCMORRIS, BENJAMIN H. LACEY, and JENNIFER R. SCHULTZ, as they are the members of THE COHASSET ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, and JOHN A. SHAW and MARTHA G. W. SHAW.