Hubbard Health Systems Real Estate, Inc. (Hubbard), filed a try title action and sought a declaration that the defendant, Michael Finamore (Finamore), in his individual capacity, doing business as Finamore MGT. Co., and doing business as Fina Mortgage Company, does not have any interest in a certain parcel of land identified by the Town of Webster as Assessor's Lot 36-B- 2-0 (Disputed Property). Finamore asks the court to deny summary judgment because Hubbard is unable to prove record title, an element required to establish standing for a try title action, and because there are disputed facts created by different plans of Hubbards property. Hubbard has shown that the different plans do not create issues of material fact and proven that it is the record owner of the Disputed Property. Leaving aside whether this obligates Finamore to appear to try his title, Hubbard is entitled under its declaratory judgment claim to a declaration of its title. Hubbard's motion for summary judgment is allowed, and judgment will enter declaring that Hubbard has title to the Disputed Property.

Procedural Background

On August 4, 2015, Hubbard filed its Complaint seeking to try title under G. L. c. 240, §§ 1-5 (Count I) and a declaratory judgment under G. L. c. 231A, §§ 1-9 (Count II). The case management conference was held on September 22, 2015. On October 23, 2015, Hubbard filed Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment, Plaintiffs Memorandum in Support of its Motion for Summary Judgment, Plaintiffs Statement of Material Facts as to which Plaintiff Contends there is no Genuine Issue to Be Tried (Pl. Facts), Appendix to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment (Pl. App.), and Affidavit of Michael H. Marsh (Marsh Aff.). On December 2, 2015, Finamore filed Defendants Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment (Def. Opp.), Defendants Response to Plaintiffs Statement of Material Facts and Statement of Additional Facts (Def. Facts), and Defendants Appendix to Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment (Def. App.). On December 11, 2015, Hubbard filed Reply of Plaintiff to Defendants Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment (Pl. Reply), Plaintiffs Response to Defendants Statement of Additional Material Facts (Pl. Resp.), and Appendix to Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment. The Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment was heard on December 21, 2015, and the case was taken under advisement. This memorandum and order follows.

Summary Judgment Standard

Summary judgment may be entered if the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court is to draw all logically permissible inferences from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991). Summary judgment is appropriate when, viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law. Regis College v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012), quoting Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991). Where the non-moving party bears the burden of proof, the burden on the moving party may be discharged by showing that there is an absence of evidence to support the non-moving party's case. Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706 , 711 (1991), citing Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 322 (1986); see Regis College, 462 Mass. at 291-292.

Undisputed Facts

For the purposes of deciding this motion for summary judgment, the following facts are undisputed or are inferred in the defendants favor:

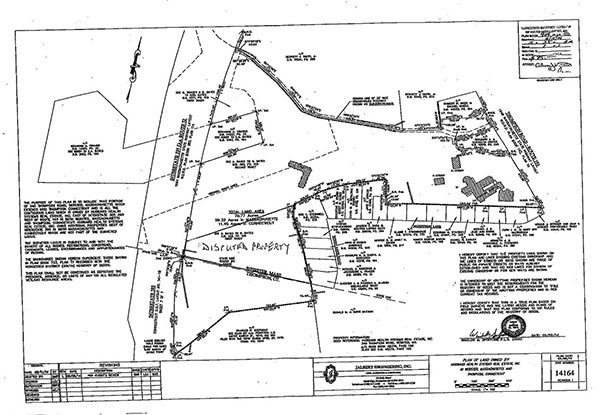

1. Finamore claims ownership over a parcel of land denoted as Assessors Lot 36-B- 2-0 in the Town of Webster Assessors Office, located in Webster, Massachusetts (Disputed Property). The Disputed Property lies east of Interstate 395 at the southern-most part of Webster, at the MassachusettsConnecticut state border. It is shown as a triangle-shaped portion of land on a plan entitled Plan of Land Owned By Hubbard Health Systems Real Estate, Inc. in Webster, Massachusetts and Thompson, Connecticut, dated September 8, 2014 and recorded on September 15, 2014 in the Worcester District Registry of Deeds (Worcester Registry) at Plan

Book 909, Plan 50 (2014 Plan). A copy of the 2014 Plan showing the Disputed Property is attached as Exhibit A. Pl. Facts ¶ 3; Def. Facts ¶ 3; Pl. App., Exhs, 3, 22-U.

2. Hubbard alleges that the land it owns is shown as an area marked as 59.32 Acres in MASSACHUSETTS, 11.45 Acres in CONNECTICUT (Hubbard Campus) on the 2014 Plan. The 2014 Plan recites that it supersedes and replaces the previous 1995 Plan, discussed further below. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 5, 8; Def. Facts ¶¶ 5, 8; Pl. App., Exhs. 3, 4.

3. The Hubbard Campus, as shown by the 2014 Plan, is bounded by Thompson Road/Route 193 on the east and Route 395 on the west. The Hubbard Campus extends into Thompson, Connecticut on the south. Pl. Facts ¶ 6; Def. Facts ¶ 6.

4. In or around 2014, Michael H. Marsh, Esq., conducted a title examination and issued a Fidelity National Title Insurance Company policy for Hubbard with respect to its property located in Webster, Massachusetts, including the Disputed Property. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 1, 13; Def. Facts ¶¶ 1, 13.

5. Hubbard claims that, pursuant to the title examination, the Disputed Property is located entirely within the Hubbard Campus. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 2, 4, 10; Marsh Aff. ¶ 8; Def. Facts ¶ 10.

Hubbards Chain of Title

6. Hubbard claims title to the Disputed Property through the Bates family chain of title.

7. Between 1837 and 1844, Nelson Bates acquired, by way of four deeds (deeds dated 1837, 1842, 1843, and 1844 and recorded in the Worcester Registry), title to property that forms the original Bates property, which included property that is now the Hubbard Campus. Pl. Facts ¶ 16; Marsh Aff. ¶ 19; Pl. App., Exh. 7.

8. In 1837, Alanson Bates conveyed to Nelson Bates two tracts of land situated in the south part of said Webster, [and] the north part of Thompson, in the state of Connecticut. The deed was dated April 4, 1837, and recorded on September 19, 1837 in the Worcester Registry, Book 329, Page 105 (1837 Deed). Pl. App., Exh. 7.

9. Tract 1 of the 1837 Deed conveyed land from the southern-westerly shore of the Chargoggagoggmanchauggaggog pond on the east, bound by land of Alanson Bates on the north, land of Joseph Tourtellotte (Tourtellotte) on the west, and lands of Tourtellotte and John Bates, Esq. on the south. The courses and distances describing the southerly border of Tract 1 closely resemble the courses and distances of the southerly border of Hubbard's property laid out in the 2014 Plan. Pl. App., Exhs. 7, 8, 22; see Marsh Aff.

10. Tourtellotte acquired the south-abutting lot from John Bates in 1830. The entire lot lies within Thompson, Connecticut. Pl. App., Exh. 22.

11. Tract 2 of the 1837 Deed conveyed property west of Tract 1, bound by Freemans land to the west and Samuel G. Butters land and Alanson Bates land to the north. Pl. App., Exh. 7.

12. In 1868, Nelson Bates conveyed all of his property to Abel Bates by a deed dated April 1, 1868, and recorded on December 2, 1868 in the Worcester Registry at Book 777, Page 592 (1868 Deed). The same deed was recorded January 2, 1876, in the Thompson, Connecticut Registry of Deeds (Thompson Registry) at Book 24, Page 283 (1875 Deed). Pl. Facts ¶ 53; Def. Facts ¶ 53; Pl. App., Exhs. 9, 23.

13. The 1868 Deed conveys the property from the south-westerly side of the Great Pond, thence westerly by land of Susan B. Davis, Alanson Bates, and Orsen Bates, to land of heirs of Rufus Freeman, thence southerly by land of said heirs of land, to land of Joseph Tourtellotte in Thompson, State of Connecticut, thence easterly by land of said Tourtellott [sic], John Bates, and Jesse Alton. The rest of the southerly border is described in detail with courses, distances, and monuments such as the road leading from Webster to Thompson (the present- day Thompson Road), barns, and railroads. Pl. App., Exhs. 9, 22-F.

14. The 1868 Deed notes that the conveyed property is approximately 100 acres in area, with 75 acres situated in Webster and 25 acres in Thompson. Pl. App., Exh. 9.

15. In 1876, Abel Bates conveyed the property he received by way of the 1868 Deed to A.J. Bates, also known as Andrew J. Bates, by a deed dated January 25, 1876, and recorded on January 26, 1876, in the Worcester Registry, Book 975, Page 109. The same deed was recorded in the Thompson Registry on January 26, 1876, in Book 24, Page 34 (1876 Deeds). Pl. Facts

¶¶ 23, 54; Def. Facts ¶¶ 23, 54; Pl. App., Exhs. 10, 24.

16. In 1885, A.J. Bates conveyed the same property back to Abel Bates by a deed dated April 1, 1881 and recorded on March 10, 1885 in the Worcester Registry at Book 1189, Page 267 (1885 Deed). The same deed was recorded on March 3, 1915 in the Thompson Registry at Book 37, Page 185 (1915 Deed). Pl. Facts ¶¶ 24, 55; Def. Facts ¶¶ 24, 55; Pl. App., Exhs. 11, 25.

17. After Abel Bates' death, his property was passed through the administration of his estate to his widow, Sarah L. Bates, his son, Summer L. Bates, and his daughter, Elsie L. Bates. Summer L. Bates did not convey away any of his interest in the property during his lifetime and died intestate, leaving his interest in the property to his widow, Annie H. Bates, and son, Abel J. Bates. Annie H. Bates conveyed portions of her interest to Abel J. Bates via deeds in 1938 and 1940, and Abel J. Bates received the remaining portions of her interest after Annie H. Bates passed away intestate. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 26-36; Def. Facts ¶¶ 26-36; Pl. App., Exhs. 12-15.

18. Elsie L. Bates did not convey away any of her interest in the property during her lifetime and died intestate in 1920, causing her mother Sarah L. Bates to inherit her interest. Sarah L. Bates died testate in 1926, leaving her interest in the property to her grandson Abel J. Bates, through a deed dated January 5, 1935, and recorded with the Worcester Registry at Book 2631, Page 254 on January 11, 1935 (1935 Deed). Thus, Abel J. Bates eventually held all of the property previously held by his grandfather, Abel Bates. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 26-36; Def. Facts ¶¶ 26-36; Pl. App., Exhs. 16-18.

19. During the Bates family ownership, other portions of the original Bates property located west of Route 395 as well as other property not part of the Hubbard Campus were conveyed out. None of these conveyances included the Disputed Property. Pl. Facts ¶ 37; Def. Facts ¶ 37.

20. Route 395 and its predecessor highway were constructed over a portion of the original Bates property, including land in both Massachusetts and Connecticut. Between 1912 and 1963, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts took portions of the original Bates property via three highway takings for the construction and alteration of Route 395 and its predecessor highway. Pl. Facts ¶ 42; Def. Facts ¶ 42.

21. In 1940 and 1954, Abel J. Bates conveyed small portions of the Hubbard Campus by Thompson Road and McGovern Lane to Webster District Hospital by a deed dated May 13, 1940, recorded on May 24, 1940 at the Worcester Registry in Book 2778, Page 214 (1940 Deed) and a deed dated August 18, 1954, recorded at the Worcester Registry in Book 3615, Page 579 (1954 Deed). Pl. Facts ¶ 39; Def. Facts ¶ 39; Pl. App., Exh. 19.

22. During Abel J. Bates' ownership, he conveyed out other portions of the original Bates property, none of which included the Disputed Property. Pl. Facts ¶ 41; Def. Facts ¶ 41.

23. In 1987, Abel J. Bates conveyed all of the original Bates property he received from the 1935 Deed (excluding the portions he had already conveyed to Hubbard, the non- disputed portions he had conveyed to others, and the takings by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts) to Hubbard Regional Hospital, the successor in interest to Webster District Hospital by a deed recorded on November 18, 1987 in the Worcester Registry at Book 10951, Page 178, and also recorded in the Thompson Registry at Book 234, Page 185 (1987 Deed). Pl. Facts ¶ 43; Def. Facts ¶ 43; Pl. App., Exhs. 20, 26.

24. In 1985, Hubbard Regional Hospital changed its name to Hubbard Health Systems, Inc. Pl. Facts ¶ 45; Def. Facts ¶ 45.

25. In 1995, a plan of the property conveyed to Hubbard was created by Jalbert Engineering dated December 20, 1995, and recorded on October 16, 1998, in the Worcester Registry in Plan Book 733, Plan 77 (1995 Plan). The 1995 Plan showed a part of the southern boundary of Hubbards property to be at the Connecticut state line and the rest of the boundary north of the Connecticut state line. The 1995 Plan referenced land that was owner unknown, portions of which lie in the Disputed Property. Def. Facts ¶¶ 74-76; Pl. Resp. ¶¶ 74-76; Pl. App., Exh. 4.

26. The 1995 Plan failed to carve out a portion near the center of the Hubbard Campus that is not actually owned by Hubbard and did not take into consideration the description of the original Bates property from the 1837 Deed. Pl. App., Exhs. 4, 29.

27. In 2012, Hubbard Health Systems, Inc., f/k/a Hubbard Regional Hospital, conveyed its ownership in the Hubbard Campus to another Hubbard entity, the plaintiff, Hubbard Health Systems Real Estate, Inc. by a deed dated November 17, 2011, and recorded at the Worcester Registry in Book 48379, Page 165, on January 9, 2012, and another deed dated November 17, 2011, and recorded at the Worcester Registry in Book 48379, Page 168 on January 9, 2012 (also recorded with the Thompson Registry at Book 774, Page 24) (2012 Deeds). Pl. Facts ¶¶ 46, 58; Def. Facts ¶¶ 46, 58; Pl. App., Exhs. 21, 27.

Finamore's Chain of Title

28. Finamore claims title to the Disputed Property through the Freeman family chain of title. The Freemans were the western abutters of the original Bates property.

29. Jean Dickinson (Dickinson) acquired an interest in property through the Freeman family chain, and, in 1996, conveyed said property to Finamore, Shareese L. Merrill (Merrill), and Brett L. Rekola (Rekola), as tenants in common, by a deed dated November 8, 1996, and recorded on November 12, 1996 in the Worcester Registry at Book 18394, Page 304 (1996 Deed). The 1996 Deed described the conveyed land as follows:

in Webster, Massachusetts, and Thompson, Connecticut, including but not limited to, the various tracts of so-called meadow and sprout land located in the rear of School Street in said Webster, Massachusetts, and Thompson, Connecticut, in which tracts Myron S. Freeman acquired an interest through Sanford L. Freeman (see Worcester Probate Court, Case No. 57525) and including, again without limitation, all the land in said Webster, Massachusetts, and Thompson, Connecticut owned by me.

Pl. Facts ¶ 61; Def. Facts ¶ 61; Pl. App., Exh. 28.

30. In 1997, Donald R. Ewell (Ewell) and Lois L. Dugan (Dugan) conveyed property to Finamore, Merrill, and Rekola, as tenants in common, by a deed dated August 4, 1997, and recorded on August 19, 1998 in the Worcester Registry, Book 20315, Page 354 (1997 Deed). The 1997 Deed uses the same property description as the 1996 Deed to Finamore, Merrill, and Rekola and pertains to land exclusively located west of Route 395. Pl. Facts ¶ 62; Def. Facts ¶ 62; Marsh Aff., ¶ 57; Pl. App., Exh. 28.

31. The 1996 and 1997 Dees show that all of the property to which Finamore has a claim relates back to the ownership of Dickinson. Neither Dickinson, Ewell, nor Dugan derive their title through the Bates chain of title covering the Hubbard Campus. Pl. Facts ¶ 71; Def. Facts ¶ 71; Marsh Aff., ¶ 58.

32. Similarly, Myron S. Freeman and Sanford L. Freeman, the Freemans mentioned in the 1996 Deed, are not owners in the Bates family chain of title to the Hubbard Campus located east of Route 395. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 65, 69; Def. Facts ¶¶ 65, 69; Marsh Aff., ¶ 58.

33. To bolster his claims of ownership, Finamore attempts to rely on a judgment obtained in Worcester Superior Court case no. WOCV2005-01476A, Michael Finamore, et. al. v. Gail Wais, et al. (Worcester Superior Court Decision) and the deeds cited therein. In the Worcester Superior Court Decision, the court held that Finamore, Merrill, and Rekola purchased all of the remaining land in Webster and Thompson owned by Dickinson through the 1996 Deed and acquired whatever interest Ewell and Dugan had in that same property through the 1997 Deed, but the precise extent of that property is not clear from the evidence presented to me at trial. Pl. Facts ¶¶ 11-12, 59-62; Def. Facts ¶¶ 11-12, 59-62; Def. App., Exh. 1; Marsh Aff., ¶ 54.

34. None of the deeds referenced in the Worcester Superior Court Decision include the Bates family chain of title, which includes the now Hubbard Campus and Disputed Property. Marsh Aff., ¶ 60.

35. Further, the 1996 and 1997 Deeds state that the tracts of land conveyed were in the rear of School Street, which is located a significant distance west of Route 395 and the Disputed Property, which is east of Route 395. Pl. Facts ¶ 66; Def. Facts ¶ 66.

36. In or around 1995, the tax assessors map labeled the Disputed Property, Lot 36- B-2, as owner unknown. In or around 1998, the tax assessors map labeled the lot as owned by Finamore. After the 2014 Plan, the tax assessors map labeled the lot as owned by Hubbard. Pl. Facts ¶ 12; Def. Facts ¶ 12; Def. Opp. p. 3; Pl. Reply p. 4.

Discussion

Hubbard has brought a claim against Finamore to try title under G. L. c. 240, §§ 1-5 and a claim seeking a declaratory judgment under G. L. c. 231A, § 1-9 that Hubbard is the record owner of the Disputed Property in which Finamore has no interest. A try title action is a creature of ancient provenance through which someone in possession of property can seek to establish that his or her rights to the property are superior to those of other named parties. Bank of New York Mellon Corp. v. Wain, 85 Mass. App. Ct. 498 , 504-505 (2014). The try title statute may now be something of an anachronism, and a property owner has other, and perhaps more suitable, remedies available to him or her. Abate v. Fremont Inv. & Loan, 470 Mass. 821 , 827 at n.13, 835 (2015), quoting Bevilacqua v. Rodriguez, 460 Mass. 762 , 766 at n.3 (2011); see Bayview Loan Serv., LLC v. Jeudy, 23 LCR 492 , 493-494 (2015). Since Hubbard is in essence seeking the same relief under both its try title claim and its declaratory judgment claim, this matter may be fully resolved on the declaratory judgment claim.

Declaratory judgment is an appropriate remedy to settle questions of property rights. Pazolt v. Director of the Div. of Marine Fisheries, 417 Mass. 565 , 569 (1994); G. L. c. 231A, § 2 (declaratory judgment may be used to secure determinations of right, duty, status or other legal relations under deeds). The purpose of a declaratory judgment is to remove, and to afford relief from, uncertainty and insecurity with respect to rights, duties, status and other legal relations. Bayview Loan Serv., 23 LCR at 493-494, quoting G. L. c. 231A, § 9. In order for the court to issue a declaratory judgment, there must be an actual controversy, a real dispute set forth in the pleadings caused by the assertion by one party of a legal relation or status or right in which he has a definite interest and the denial of such assertion by the other party, where the circumstances . . . . indicate that, unless a determination is had, subsequent litigation as to the identical subject matter will ensue. Hogan v. Hogan 320 Mass. 658 , 662 (1947); see also G. L. c. 231A, § 1. Declaratory relief is to be liberally constructed and administered. G. L. c. 231A, § 9; Spillane v. Adams, 76 Mass. App. Ct. 378 , 386 (2010) (the trial judge had ample latitude to establish the [parties] title and adjudicate the boundaries when title was at issue). In fact, when an action for declaratory relief is properly brought, even if relief is denied on the merits, there must be a declaration of the rights of the parties. Id., quoting Boston v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Auth., 373 Mass. 819 , 829 (1977). Here, Hubbard and Finamore both assert that they are the record owner of the Disputed Property. Thus, there is an actual controversy regarding the status of title upon which the court must rule.

The resolution of this case turns on determining where the southern boundary of the Hubbard Campus lies, which in turn will determine whether the Disputed Property falls within the bounds of Hubbards ownership. When a boundary line is in controversy, it is a question of fact on all the evidence, including the various surveys and plans. Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 679 (2004), quoting Hurlbut Rogers Mac. Co. v. Boston & Maine R.R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). Deed construction is a part of that analysis. Generally, the meaning of a deed, derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 174 , 179 (1998). Rules of deed construction provide a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Paull, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 680. When abutter calls are used to describe property, abutters' lands are considered monuments. Id.; C.M. Brown, et al., Brown's Boundary Control and Legal Principles 387-388 (4th Ed., 1995) (Bound descriptions generally eliminate gaps and overlaps since abutting descriptions calling for one another ensure one common line between them. Courts have generally ruled that abutters, if identifiable, are classed as monuments and must be honored.).

Hubbard claims it holds record title over the entirety of the Hubbard Campus and the Disputed Property through the Bates family's chain of title, specifically, land derived from Alanson Bates and Nelson Bates. Finamore argues that these deeds lack identifiable descriptions and bounds and, thus, Hubbard cannot establish record title.

Between 1837 and 1844, Nelson Bates acquired the original Bates property through a series of deed conveyances, the 1837 Deed being the most significant conveyance for purposes of this action. In 1837, Alanson Bates conveyed to Nelson Bates two adjacent tracts of land situated in the south part of said Webster, [and] the north part of Thompson, in the state of Connecticut. Together, the two tracts made up a piece of land that starts from the westerly shore of present-day Webster Lake (formerly Chargoggagoggmanchauggaggog pond), extends north to Samuel G. Butters land and Alanson Bates land, extends west to Freemans land and Joseph Tourtellottes (Tourtellotte) land (south of Freemans land), and extends south to Tourtellotte's land and John Bates, Esq.s land. Essentially, the property is a long strip of land that extends west from the shore of Webster Lake more than 300 rods, or 5000 feet, approximately one mile. In describing the property, stakes and stones were used in reference to the boundaries of the abutters lands. The title examination, completed Attorney Marsh, revealed that Tourtellottes southern property, acquired from John Bates in 1830, lies entirely within Thompson, meaning the southern boundary of the original Bates property extended into Connecticut. This is consistent with the language in the 1837 Deed, which grants land that extends into Thompson, Connecticut.

These tracts are also described with courses and distances. The majority of courses and distances describing the southerly border closely match, within inches, those of the present-day southerly border of the Hubbard Campus, depicted in the 2014 Plan. Additionally, one of the monuments used to describe southerly border in the 1837 Deed is the road leading from said Webster to said Thompson, a road that matches the location of present-day Thompson Road as shown on the 2014 Plan. The 1837 Deed succinctly describes the southern bound of the original Bates property using precise monuments, abutter calls, and courses and distances. Based on the location of the southerly boundary line in this deed, the Disputed Property lies within the Hubbard Campus.

Likewise, the 1868 Deed provides support that title to the Disputed Property is with Hubbard. In 1868, Nelson Bates conveyed the original Bates property to Abel Bates, which is noted in the deed as consisting of approximately 75 acres in Webster, and 25 acres in Thompson. The deed was recorded in both Massachusetts and Connecticut. This deed also uses abutter calls and references stakes and stones as monuments to describe the limits of the property. The property is bounded on the north by the lands of Susan P. Davis, Alanson Bates, and Orsen Bates, on the west by land of Rufus Freeman in Massachusetts and Tourtellotte in Connecticut, and on the south by land of Tourtellotte, John Bates, and Jesse Alton. These abutter calls are the same as in the 1837 Deed, with the exception of a few additional abutters. The 1868 Deed specifically calls out Toutellottes land in defining the western and southern bounds of the Bates property, demonstrating that portions of the western border and southern border extend into Connecticut. While Finamore argues that these deeds are vague because they refer to stakes and stones, the use of stakes and stones as monuments in describing the bounds of the abutters land is on the top of the hierarchy for deed description and should be given weight. Though some portions of the southern border of the property in the 1868 Deed are described with courses and distances, clear monuments such as the road leading from Webster to Thompson (the present- day Thompson Road), barns, and railroads are also used in the description that allow the southern boundary to be accurately defined. It is irrelevant that courses and distances in some portions of the property near Thompson Road do not match those in the 1837 Deed because this area is not proximate to the Disputed Property.

The chain of title for the original Bates property can easily be followed through the latter half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. In 1876, Abel Bates conveyed the property he received from the 1868 Deed to A.J. Bates by a deed recorded in both Massachusetts and Connecticut. A.J. Bates conveyed the same property back to Abel Bates in 1885 by a deed which was recorded in both Massachusetts and Connecticut. After Abel Bates' death, the property was left to his widow, Sarah L. Bates, his son, Summer L. Bates, and his daughter, Elsie L. Bates. Elsie died intestate, leaving her share to her mother, Sarah, who eventually left all her property to Abel J. Bates, her grandson, son of Summer. Summer left his share to his son, Abel J., and his widow, Annie. H. Bates, who deeded her interest to Abel J. In short, Abel J. Bates became the sole owner of the original Bates property.

Thereafter, portions of the original Bates property located in both Massachusetts and Connecticut were taken for the construction and alteration of Route 395 and its predecessor highway. In addition, during the Bates family ownership, portions of the original Bates property located west of Route 395, as well as portions of the original Bates property east of Route 395 (but not a part of the Hubbard Campus), were conveyed. Both parties agree that none of these conveyances included the Hubbard Campus or the Disputed Property. During Abel J. Bates' ownership, he also conveyed out other portions of the original Bates property, none of which included the Hubbard Campus or Disputed Property. Most important, there is no record of the Bates family, including Abel J. Bates, conveying away the portion of the original Bates property east of Route 395, near or below the MassachusettsConnecticut border. Thus, the Hubbard Campus, which lies immediately east of Route 395 and west of Thompson Road, above and below the MassachusettsConnecticut border, remained intact and under the ownership of Abel J. Bates. This means that the southern boundary of the remainder of the original Bates property near the Disputed Property did not change over the years and is the same boundary as shown in the 2014 Plan as the one described in the 1837 and 1868 Deeds.

Between 1940 and 1954, Abel J. Bates conveyed small portions of the original Bates property to Webster District Hospital, Hubbard's predecessor. In 1987, Abel J. Bates conveyed to Hubbard the remainder of the original Bates property, excluding the portions he had already conveyed to Hubbard, the non-disputed portions he had conveyed to others, and the takings for Route 395. The Disputed Property, a triangular lot immediately north of the Massachusetts Connecticut border and immediately east of Route 395, falls squarely within the remainder of the original Bates property, or the land Hubbard now owns. As a result, the evidence corroborates that Hubbard is the record owner of the Disputed Property.

Finamore also contends that because the southern boundary is different on the 1995 Plan than the 2014 Plan this creates a dispute of fact. This is unpersuasive. The record demonstrates that the southern boundary shown in the 1995 Plan was simply incorrect. As drawn on the 1995 Plan, the southern boundary of the Hubbard Campus, or the original Bates property, ends slightly north of the MassachusettsConnecticut border in Massachusetts, and part of the currently Disputed Property is marked as owner unknown. The 1995 Plan didnt account for the 1837 Deed and boundary descriptions therein. It relied on abutter calls in certain subdivision plans to draw the boundaries, but the subdivision plans relied upon were inaccurate and listed certain abutters as being in Webster, Massachusetts when they were in fact in Thompson, Connecticut. The plan also failed to carve out a portion of the Hubbard Campus not owned by Hubbard. Jalbert Engineering, the same company that drafted the 1995 Plan, redrew the 2014 Plan and re- recorded it in the Worcester Registry, replacing the 1995 Plan. The numerous deviations in the 1995 Plan do not create a dispute of fact that forecloses summary judgment. Rather, these are undisputed mistakes that make the 1995 Plan an inaccurate plan, which was in fact later rescinded.

To the extent that Finamore relies on the labeling of the Disputed Property on the tax assessors map as a separate lot with different owners over time (owner unknown, then Finamore, now Hubbard) as creating a dispute of fact, this reliance is misplaced. Generally, a tax assessor's map has nothing to do with title. Waters v. Cook, 13 LCR 553 , 557 (2005) (discrepancies between a property's ANR plan and the tax assessor's map does not constitute a title defect). The fact that the tax assessors map previously labeled the Disputed Property as having an unknown owner, and then being owned by Finamore, is not conclusive of title. It merely shows that different parties have or have not claimed ownership of the Disputed Property for tax purposes.

Moreover, the deeds Finamore provides do not establish his title to the Disputed Property. Finamore provides the 1996 and 1997 Deeds in which he acquired property, to the west of Route 395, which Dickinson, Ewell and Dugan, received through the Freeman familys chain of title, including but not limited to, the various tracts of so-called meadow and sprout land located in the rear of School Street in said Webster, Massachusetts, and Thompson, Connecticut. The judgment in the Worcester Superior Court Decision, which references the 1996 and 1997 Deeds, stated that Finamore, Merrill, and Rekola purchased all of the remaining land in Webster and Thompson owned by Dickinson through the 1996 Deed and acquired whatever interest Ewell and Dugan had in that same property through the 1997 Deed, but the precise extent of that property is not clear from the evidence presented. What is clear, however, is that none of these deeds include the Bates family chain of title. The Freemans were the western abutters of the original Bates property, which extended far west beyond the current-day Route 395 and the Disputed Property, which lies east of Route 395. Thus, even if Finamore did acquire land from the Freeman family chain of title, the land did not consist of property near the Disputed Property. Accordingly, Finamore does not have any interest in the original Bates property, which includes the Disputed Property.

Conclusion

Based on the foregoing, Hubbard has record title over the entirety of the Hubbard Campus, including the Disputed Property. Finamore has not presented sufficient evidence to prove he has any interest in the Disputed Property. As such, the Plaintiff's Motion for Summary Judgment is ALLOWED. Judgment shall enter declaring that Hubbard is the owner of the Disputed Property shown on the 2014 Plan, and that Finamore has no title to said property.

SO ORDERED

HUBBARD HEALTH SYSTEMS REAL ESTATE, INC. v. MICHAEL FINAMORE, in his individual capacity and d/b/a FINAMORE MGT. CO. and d/b/a FINA MORTGAGE COMPANY.

HUBBARD HEALTH SYSTEMS REAL ESTATE, INC. v. MICHAEL FINAMORE, in his individual capacity and d/b/a FINAMORE MGT. CO. and d/b/a FINA MORTGAGE COMPANY.