INTRODUCTION

This long-running dispute involves Plaintiffs' claims to hold deeded rights in an approximately 1.7-mile stretch of beach on the south shore of Martha's Vineyard, or alternatively to have acquired prescriptive rights to use that beach. On April 20, 2011, judgment entered in the Land Court that Plaintiffs hold no deeded interest in the beach as it exists today, do not have an express easement to use the Road to Short Point for beach access, and do not hold any express or implied easement over Paqua. Additionally, the Judgment dismissed Plaintiffs complaint, ruling that Plaintiffs had not "met their burden of proof to establish the existence of the prescriptive easements they claim in this action." See generally, Hamilton v. Myerow, 19 LCR 176 (2011) (Misc. Case No. 04-303223) (Trombly, J.). [Note 3]

Upon direct appellate review of the April 20, 2011 Judgment, the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) affirmed "that portion of the judgment declaring that [Plaintiffs] do not have a title interest in the beach as it exists today, since their title interest is to a beach now submerged under the Atlantic Ocean." White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 402-03 (2013). [Note 4] However, with respect to Plaintiffs' alternative prescriptive beach easement claim, the SJC concluded that "the record does not contain such subsidiary findings of fact as are necessary to permit adequate review of the judge's conclusion that [Plaintiffs'] use of the beach [as it exists today] was not open and notorious, adverse, or for a period of twenty years." Id. at 420. Accordingly, the SJC vacated "[s]o much of the judgment as declares that the plaintiffs have not established a prescriptive easement to use the beach," and "remanded [the matter] to the Land Court for further proceedings, as necessary, and for findings of fact, consistent with this opinion." Id. at 423. The SJC took "no view on whether the evidence produced at trial is sufficient to support the conclusion that [Plaintiffs] did not establish a prescriptive easement; we simply require additional findings of fact, based on this evidence, so as to permit an adequate review." Id. at 420.

After remand and re-assignment to a new judge (Cutler, C.J.), [Note 5] the Parties were given an opportunity to argue their positions as to whether or not it would be necessary to conduct either a new trial or further evidentiary hearings. On May 10, 2013, the Defendant Trustees of the Pohogonot Trust and the Defendant Trustee of the RABOR, TAROB, and BOTAR Realty Trusts moved for a new trial pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 63, later joined by the Defendant Trustee of the Job's Neck Trust. Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' motion for a new trial was filed on May 24, 2013. Following a hearing on May 28, 2013, the court deferred action on the motion in order to allow the Parties an opportunity to submit proposed findings of fact and rulings of law, based upon 2011 trial evidence and testimony, as well as any stipulated facts. The Parties filed their respective Proposed Findings of Fact and Requested Rulings of Law on September 9, 2013. Following a series of motions, status conferences, and hearings, the court ultimately determined that neither a new trial nor further evidentiary hearing would be necessary, and that it would adjudicate the prescriptive easement claim and make the subsidiary findings based upon the existing trial record. [Note 6] On January 14, 2015, the court heard the Parties' oral arguments on the basis of that record, and took the prescriptive beach easement claim under advisement.

Now, based on my subsidiary findings of fact as set forth below, and for the reasons discussed herein, I conclude that Plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of establishing a prescriptive beach easement over the "whole" beach, as they claim, nor any part thereof.

Plaintiffs have not established any prescriptive beach rights, either because their various uses of the beach were occasional and sporadic, did not continue uninterrupted for the full, requisite twenty-year period, and/or were not substantially confined to a regular part or parts of the beach.

RELEVANT BACKGROUND FACTS

1. The beach in dispute is an approximately 50-acre, 1.7-mile stretch of beach located in Edgartown, Dukes County, Massachusetts on the southern coast of Martha's Vineyard (the "Beach"). [Note 7] Its southern boundary is the Atlantic Ocean. [Note 8]

2. The southern shoreline of Martha's Vineyard has retreated in a northward direction from 1846 to the present date, due to a combination of sea level rise, waves, tides, storms, and winds. [Note 9] As a result, the northern boundary of the Beach is migrating further northward each year.

3. For many generations, two families the Norton family and the Flynn family each owned land in the southwest corner of Edgartown. The Flynn land holdings include what is today the disputed Beach.

4. At one time, both the Flynn family holdings and the Norton family holdings included fractional interests in a beach parcel abutting what are known as the Pohogonot and Paqua properties (eventual Flynn family holdings). However, that beach parcel became submerged beneath the Atlantic Ocean no later than 1938. See White, 464 Mass. at 413. As a result of the northward migrating shoreline, the now-existing Beach in dispute lies on what was formerly upland and the beds of coastal ponds, and is distinct from the now- submerged beach.

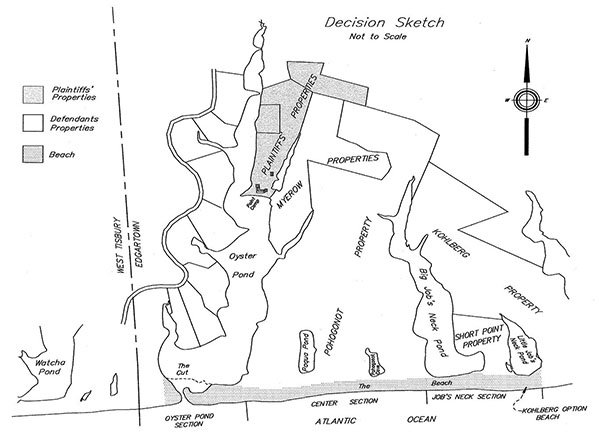

5. The Beach includes three main segments, which are depicted on the attached Decision Sketch:

a) The "Job's Neck Section" refers to the easternmost segment of the Beach, extending from the western edge of Big Job's Neck Pond to the eastern edge of Little Job's Neck Pond. It is directly south of Big Job's Neck Pond, the Short Point Property, and includes the approximately 4.4-acre "Kohlberg Option Beach" that lies below Little Job's Neck Pond. The Job's Neck Section of the Beach includes two fairly-distinct barrier beaches: one located below Big Job's Neck Pond, and one below Little Job's Neck Pond, which separate these Ponds from the Atlantic Ocean.

b) The "Center Section" refers to the stretch of the Beach running from the eastern edge of Oyster Pond to the western edge of Big Job's Neck Pond.

c) The "Oyster Pond Section" refers to the barrier beach on the western end of the Beach, separating Oyster Pond from the Atlantic Ocean. This barrier beach is "cut" open once each year to allow salt water from the Atlantic Ocean into the Pond.

6. Plaintiffs herein are various members of the Norton family and their successors-in-interest (collectively, the "Nortons"/"Plaintiffs"). [Note 10] Plaintiffs own properties located to the northeast of Oyster Pond, either individually or as Trustees. The sole access from their properties to the Beach is by boat across Oyster Pond, to the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach. [Note 11]

7. Defendants include a limited liability corporation and the Trustees of six real estate trusts, each of which holds title to one or more parcels of the original Flynn family holdings, including title to or rights in the disputed Beach. [Note 12]

a) The Pohogonot Trust owns approximately 431 acres bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the south, Oyster Pond on the west, and Job's Neck Pond on the east ("Pohogonot Property"). The Pohogonot Property includes within it a majority of the Beach in disputerunning from the Oyster-Watcha Line to approximately the western edge of Little Job's Neck Pond, where the Kohlberg Option Beach begins.

b) Michael Myerow, as Trustee of RABOR, TAROB, and BOTAR Trusts, owns land to the north between Oyster Pond and Job's Neck Pond acquired from the Pohogonot Trust in February 2001 (the "Myerow Properties"). The Myerow Properties abut the Pohogonot Property to the northwest. The Myerow defendants have a recorded easement to use a portion of the Beach near Oyster Pond. [Note 13]

c) Pamela Kohlberg, as Trustee of Job's Neck Trust, owns land east of Job's Neck Pond acquired from the Pohogonot Trust in 1995 (the "Kohlberg Property"). The Job's Neck Trust also owns an approximately 4.4-acre parcel of the Beach at its easternmost end, situated directly below Little Job's Neck Pond (the "Kohlberg Option Beach").

d) Andrew Kohlberg, as Trustee of the High Road Trust, owns upland property northeast of the Kohlberg Property (not depicted on the Decision Sketch).

e) Short Point Holdings, LLC owns an approximately thirty-acre parcel acquired from the Pohogonot Trust in 1998 (the "Short Point Property"). It is bounded by Big Job's Neck Pond on the west, Little Job's Neck Pond on the east, the portion of the Beach owned by Pohogonot Trust on the south, and the Kohlberg Property on the north.

8. In the 1930s, Frank L. Norton and Elizabeth Norton (grandparents of Plaintiff Allen Norton) owned a large swath of land northeasterly of Oyster Pond, running north towards the state highway, including the areas known as "Nonamessett" and "Quampachy" (collectively, the "Oyster Pond Property"). The Oyster Pond Property eventually passed to Winthrop ("Sonny") Norton in 1951.

9. Between 1951 and 1981, Sonny Norton and George D. Flynn, Jr. ("Uncle George") the patriarchs of the Norton and Flynn families, respectively controlled their family properties.

10. Plaintiffs herein who are members of the Norton family include: Allen Norton and several members of his immediate family, along with Plaintiff Albert White (Wilda White's widower) and several of their daughters.

11. After Sonny died in 1981, the Norton family began selling off parcels of the Oyster Pond Property. All of Plaintiffs acquired interests in their respective properties out of what was once the Oyster Pond Property owned by Sonny Norton. [Note 14]

12. In 1983, the Nortons sold a parcel of the Oyster Pond Property to Richard Friedman ("Friedman"), who also began using portions of the Beach. Friedman acquired additional parcels of the Oyster Pond Property in 1995 and 1997.

13. The controversy over rights to access and use the Beach appears to have been sparked after Allen Norton began selling and conveying portions of the Oyster Pond Property outside of the Norton family. When Plaintiff Friedman acquired his property and began riding on horseback on the beach and across Flynn land, Flynn family members asked him not to do so, and began to more openly question the rights of the Nortons' and their successors-in-interest to use the Beach and various paths. Ultimately, in November, 1999, the Flynns caused a public notice of their intention to prevent the acquisition of easements over their lands to be posted, served, and recorded in accordance with G. L. c. 187, §§ 3 and 4. [Note 15]

Additional facts pertinent to the Beach and the uses of the Beach between 1938 and 1999 are set forth in the discussion below.

DISCUSSION

Issues on Remand

Plaintiffs seek a prescriptive beach easement over the entire Beach for "usual and customary beach uses and purposes throughout the year, in common with all others legally entitled to use the [Beach]." They claim to have used the entire 1.7 mile length of Beach adversely, notoriously and continuously since at least 1938. In doing so, Plaintiffs rely on an accumulation of various uses and activities conducted by numerous members of the Norton family (especially Plaintiff Allen Norton), their tenants, and guests in the years between 1938 and 1999, in several locations on the Beach. These uses and activities included swimming, sunbathing, clamming, and picnicking during the summer season, as well as riding the Beach in vehicles and on horseback, fishing, duck hunting, and surfcasting throughout different seasons of the year.

On remand from the SJC, this court is required to make subsidiary findings of fact relative to whether Plaintiffs met their burden at trial to establish a prescriptive beach easement. That is, this court is required to make findings of fact relative to whether the Norton Family used the Beach for beach purposes, continuously and without interruption for at least twenty years during the period running from 1938 to November 1999, and whether the Nortons' use of the Beach was open, notorious, and adverse.

Prescriptive Easement Standard

"An easement by prescription is acquired by the (1) continuous and uninterrupted, (2) open and notorious, and (3) adverse use of another's land (4) for a period of not less than twenty

years." White, 464 Mass. at 413; see also G.L. c. 187, § 2. Plaintiffs must demonstrate their entitlement to prescriptive rights in the Beach by "clear proof." Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 835 (2008) (citing Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007)). "The burden of proving every element of an easement by prescription rests entirely with the claimant. If any element remains unproven or left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009). As discussed below, I find, as a threshold matter, that Plaintiffs have met their burden to show that their use of the Beach in the period between 1938 and 1999 was open, notorious, and adverse. However, Plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that their use continued for any uninterrupted twenty-year period.

The Nortons Used the Beach Openly and Notoriously

The requirement that a party's adverse use of another's land be "open and notorious" centers on notice to the affected landowner, and "'is intended only to secure to the owner a fair chance of protecting himself.'" White, 464 Mass. at 417 (quoting Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 218 (1955)). "'To be 'open,' the use must be without attempted concealment'; to be notorious, the use must put the landowner on constructive notice of the adverse use." White, 464 Mass. at 416 (quoting Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44). The character of the affected land determines what level of openness and notoriety is required to acquire title by adverse use.

Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. As to beach property, seasonal use for bathing, picnicking, and other recreational activities usually associated with beaches, constitutes open and notorious use. See, e.g., Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 (1967). [Note 16]

The evidence supports a finding that the Norton family's various uses of the Beach were openthat is, without attempted concealment. The evidence reveals that the Nortons believed they owned a fractional interest in the Beach and had every right to be there, and thus the Nortons had no reason to conceal their usage, and did not do so. That the Norton family kept its distance from the Flynn family out of respect for privacy (and not as an attempt to conceal their presence) is borne out by consistent testimony, including acknowledgments by several Flynn family members. Flynn family members, Harry Flynn, Judy Flynn Palmer, Dorothy Chafee, Florence Peters, and John Flynn all testified to encountering members of the Norton family making various uses of the Beach on a number of occasions over the years. Both Norton and Flynn family members (e.g., Natalie Conroy (Norton), Dorothy Chaffee (Flynn), and Florence Peters (Flynn)) also testified to encountering one another during their respective Sunday gatheringsusually in the Oyster Pond Section in the later years, where the two families would congregate on opposite sides of the barrier beach cut to the ocean.

This same evidence also supports the conclusion that the Nortons' uses of the Beach were notoriousthat is, either actually known to the Flynns, or sufficient to put the Flynns on constructive notice of adverse use. See Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44 ("For a use to be found notorious, it must be sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property."); see also Foot, 333 Mass. at 218 ("'To be notorious [the use] must be known to some who might reasonably be expected to communicate their knowledge to the owner if he maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over his premises.'" (quoting American Law of Property § 8.56)). Here the Flynn family members' testimony that they observed the Nortons using the Beach in various locations and at various times over the years, is sufficient to support a finding of actual knowledge.

Because the evidence bears out that the Nortons made no attempt to conceal their use of the Beach during the relevant time period, and that the Flynns actually knew of the Nortons' uses of the Beach, I find that the Nortons met their burden to show that when they used the Beach in the years between 1938 and 1999, their use was both open and notorious.

The Nortons Used the Beach Adversely

"To be adverse, the use must be made under a claim of right." White, 464 Mass. at 418 (citing Gower v. Saugus, 315 Mass. 677 , 681-82 (1944)). "'[W]herever there has been the use of an easement for twenty years unexplained, it will be presumed to be under claim of right and adverse, and will be sufficient to establish title by prescription . . . unless controlled or explained.'" Ivons-Nispel, Inc. v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 763 (1964) (quoting Flynn v. Korsack, 343 Mass. 15 , 18 (1961)).

The trial testimony and evidence bear out the Nortons' assertion that they used the Beach under a sincere belief that they owned a deeded, fractional interest therein. Although the SJC in White affirmed that the Nortons did not in fact own a fractional interest in the Beach as it exists today (their deeded interest being confined to the boundaries of a now-submerged parcel of land), the great weight of the evidence suggests that, throughout the majority of the time period under consideration (1938 to 1999), the Norton family and the Flynn family both believed that the Nortons held an ownership interest in the entirety of the Beach as it existed from 1938 onward.

In 1950, Uncle George and Sonny, together, engaged attorney Harry Perlstein to provide a legal opinion on the ownership interests in the then-existing beach. The Perlstein Opinion concluded that the Flynns owned an approximately three-fifths interest, and the Nortons owned an approximately one-fifth interest. There is no evidence in the trial record that Uncle George or any other Flynn family members repudiated or rejected the Perlstein Opinion either at the time it was rendered, or in the over-thirty years that followed. [Note 17]

To the contrary, the trial record contains several examples of the Flynns' recognition of the Nortons' claim of right to use the Beach as fractional owners. Growing up, John Flynn was told by Uncle George and his father that the Nortons owned a fractional interest in the Beach "running from Oyster Pond all the way to Job's Neck." In May 1982, Uncle George wrote a note to John Flynn that was critical of Allen Norton's actions in conveying beach rights with the sale of certain Norton Properties, but that nonetheless acknowledged Sonny's long-time claim to own a one-fifth interest in the Beach, noting: "Sonny always said 'I own a fifth of the beach.'" Moreover, when John Flynn, at the behest of Uncle George, confronted Allen about his sale of fractional beach interests, Allen unequivocally asserted his ownership interest in the Beach and cited the Perlstein Opinion. When John Flynn then asked Uncle George about the Perlstein Opinion, Uncle George gave him a copy, and the Flynns thereafter ceased challenging Allen's authority to convey the Norton Properties with beach rights. [Note 18]

Accordingly, I find that the Nortons used the Beach under a claim of right and that the Flynns recognized that claim. Moreover, even if the Flynns did not agree with the Nortons' ownership claim, they took no definitive action to stop the Nortons from using the Beach until November, 1999 when they posted the notice to prevent the acquisition of easement pursuant to G. L. c. 187, §§ 3 and 4. Any uses the Nortons made of the Beach under claim of right between 1938 and 1999 were, consequently, adverse. See Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836 ("[A]dverse possession may exist where there is possession with the forbearance of the owner who knew of such possession and did not prohibit it but tacitly agreed thereto.")

Likewise, the evidence is sufficient to establish that, contrary to Defendants' assertions, the Nortons' use of the Beach was without "permission" from the Flynns. There are no specific examples in the trial record of the Nortons either seeking or obtaining permission from the Flynns for any of their uses of the Beach between 1938 and 1999, as distinguished from seeking and obtaining permission to use the Flynn upland properties, roads, or paths. See, e.g., White, 464 Mass. at 418 & ns. 23 & 24. Defendants call attention to a time around 1989 or 1990 when Shauna White Smith (Norton) contacted Florence Peters (Flynn) to ask permission to traverse the Short Point Property to head to a beach near Edgartown Great Pond. However, there is nothing remarkable about Shauna White Smith seeking permission to cross the Flynns' upland Short Point Property; nor does her request suggest an acknowledgement that the Nortons had no claim of right to cross over the Beach itself. [Note 19]

Similarly, the testimony from some Flynn family members that Albert White and Allen Norton each obtained "blanket permission" from Uncle George to pass over or use certain portions of the Flynn Properties for hunting or fishing is not at all inconsistent with the Nortons' testimony that they believed they did not need permission to use the Beach because they owned fractional beach rights. It merely reflects the Nortons' recognition that permission was required to traverse or use the Flynns' upland properties, even if only to get to the Beach. Because the Nortons used the Beach under a claim of right (notwithstanding that their claim ultimately proved to be mistaken), the evidence shows that they did not seek or obtain permission from the Flynns to use the Beach. Accordingly, I find that any uses the Nortons' made of the Beach during the relevant time period were adverse.

The Nortons Did Not Continuously Use a Regular or Particular Part of the Beach

My findings that the Norton family's uses of the Beach during the period from 1938 to 1999 were open, notorious, and adverse do not depend upon subsidiary findings as to the type or frequency of their uses, the location(s) of their uses, or the timing and continuity of use. Plaintiffs are mistaken in relying on various Flynn family "acknowledgements" of having observed the Norton family's beach uses to demonstrate thatin addition to "open and notorious" usethe Nortons' used the entire beach continuously and without interruption for more than twenty years. Notwithstanding the several occasions between 1938 and 1999 when the Flynns encountered the Nortons on the Beach, Plaintiffs still carry the burden to demonstrate a consistent, regular pattern of their beach uses that continued for at least twenty years in one or more defined locations. They cannot simply rely upon a cumulative set of sporadic, disjointed, or intermittent uses occurring in several different locations at different times over the span of sixty years.

"Continuous" use need not be "constant." Bodfish v. Bodfish, 105 Mass. 317 , 319 (1870). And seasonal use will not defeat a claim for a prescriptive easement when seasonal property is at issue. See Mahoney v. Heeber, 343 Mass. 770 , 770 (1961) ("Seasonal absence of plaintiff and his predecessors from their summer home did not require a finding that the adverse use was not continuous"); see also Lawrence v. Houghton, 296 Mass. 407 , 409 (1937) ("The fact that the land and the road were not used in the winter did not destroy the continuity of the use of the road for purpose of prescription."). One may, therefore, acquire an easement by prescription over a beach, notwithstanding the traditionally seasonal uses associated with such land. See, e.g., Ivons-Nispel, 347 Mass. at 762-63; Labounty, 352 Mass. at 348. Nevertheless, a claimant must at least establish a pattern of regular or consistent use throughout the statutory twenty-year period. See Stagman v. Kyhos, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 590 , 593 (1985). Uses which are "intermittent" or "disjointed" in time are insufficient, Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45, as are sporadic uses. Cf. Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 , 540 (1996).

The Nortons endeavor to show their "continuous and uninterrupted" use of the "entire" Beach over the course of sixty years by adding together several different activities conducted on one or more of the distinct Beach Sections, by multiple family members, guests, or tenants, within several different time periods. Citing a case from North Carolina, Concerned Citizens of Brunswick County Taxpayer's Assn. v. State, 404 S.E.2d 677, 684 (N.C. 1991), the Nortons argue that they need not establish that they used each and every square foot of the Beach, so long as their use was extensive enough to show a claim to the entire beach during the prescriptive period. In Concerned Citizens, the North Carolina court determined that deviations in the use of a "dynamic" beach path through shifting sand dunes were "slight" or insubstantial and did not defeat a claim to a public prescriptive easement of travel. Id. at 684.

The standard in Massachusetts, however, is not as relaxed as Plaintiffs urge; nor does the Concerned Citizens case stand for the expansive proposition that Plaintiffs press. The extent of any prescriptive right created by twenty years of continuous and uninterrupted use is measured by the type, extent, and location of the use made during the prescriptive period. It is settled in Massachusetts that, in order to establish a prescriptive easement, the claimant must prove that the adverse use was "substantially confined" to a specific part of the parcel. See Boothroyd, 69 Mass. App. Ct. at 45 ("The law as to this specific evidentiary element is well-settled."); see also Stone v. Perkins, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 265 , 268 (2003) ("[T]he absence of a definite location renders doubtful whether the adverse use was sufficiently notorious and continuous to place the potentially servient landowner on notice of the adverse right that is maturing."); Bruce & Ely, The Law of Easements and Licenses in Land § 5:12 (2015) ("In other words, the prescriptive use must define the boundary of the easement with reasonable certainty."). [Note 20] Thus, under the applicable legal standard, although a claimant need not show the existence of a single or the same definite and specific line of travel or location of use to acquire a prescriptive easement, the evidence must nonetheless show that the claimant's use was "'confined substantially' to a regular or particular trail or part of the locus." Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 46 (emphasis added). [Note 21]

Moreover, case law does not support Plaintiffs' assertion that they may cobble together distinct periods of use made of different sections of the Beach to acquire prescriptive rights to use the whole 1.7-mile long Beach. See Glenn v. Poole, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 292 (1981) ("The extent of an easement arising by prescription

is fixed by the use through which it was created."); see also Dahlgren v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 210 Mass. 243 , 245 (1911) ("Nor could a prescriptive right in the more recent way be acquired by tacking together two distinct periods of use of the two substantially different routes.").

With this guidance in mind, [Note 22] and after examining the evidence as to the size and character of the Beach and the patterns of land ownership adjacent to the Beach, as well as the types of uses and activities the Nortons conducted on the Beach, the location(s) on the Beach where such activities were shown to have occurred, and the periods of time during which they occurred, I find that the evidence and testimony does not sustain the Nortons' claim to have adversely used the whole beach consistently, uninterruptedly, or regularly for twenty years or more. I reach the same finding for each given Section of the beach, where no continuous period of use in such Section extended the requisite twenty years. Below, I discuss, in the context of each of the three Beach Sections (the Job's Neck, Center, and Oyster Pond Sections), the uses alleged to have occurred in each Section, and the alleged period of time such uses continued, in order to determine whether the Nortons have demonstrated by clear evidence that they used any of these Beach Sections for beach purposes, continuously, and uninterruptedly for a period of at least twenty years.

Use of the Job's Neck Section

Plaintiffs failed to demonstrate continuous and uninterrupted beach use of the Job's Neck Section of the Beach for the twenty-year period from 1938 to 1958. Most importantly, Plaintiffs provided no reliable evidence of use of the Job's Neck Section during the two-year period when Allen was stationed with the U.S. military in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from 1956 to 1958. [Note 23] This two-year gap in the evidence of beach use, prevents creation of a prescriptive easement in the period between 1938 and 1958.

Between 1958 and the early 1980s, the Norton family gathered on summer Sundays in the Job's Neck Section of the Beach approximately 75-80% of the time. The testimony as to the frequency and regularity of their gatherings on the Job's Neck Section of the Beach over this twenty-plus year time period, however, is not sufficient to establish continuous use, when viewed in light of the drastically inconsistent testimony of the Norton witnesses as to where in the Job's Neck Section the Norton family gathered during this period. Allen and his daughter Melissa both testified that they usually gathered below Big Job's Neck Pond, and only occasionally used the area below Little Job's Neck Pond (the Kohlberg Option Beach). [Note 24] But Allen's wife, Judy, testified that the family usually gathered below Little Job's Neck Pond, and only "once in a while" gathered below Big Job's Neck Pond. [Note 25] Mark Norton, Allen's son, and Shauna White Smith, Wilda's daughter, each testified that the family alternated using the areas below both of these ponds, but neither quantified the frequency that either area was used. John Flynn acknowledged seeing the Nortons occasionally using the southwestern corner of Big Job's Neck Pond for their summer gatherings.

To meet their burden of proof, Plaintiffs had to demonstrate that their beach use was "substantially confined" to a specific "part of the locus." Boothroyd, 69 Mass. App. Ct. at 45. Even with respect to the Job's Neck Section (as opposed to the whole Beach), this is not an insignificant matter considering that the Job's Neck Section of the Beach spans over half a mile in length from the southwestern corner of Big Job's Neck Pond to the southeastern corner of Little Job's Neck Pond. It includes the two barrier beaches below Big Job's Neck Pond and Little Job's Neck Pond (the Kohlberg Option Beach), and the beach area between the two Job's Neck Ponds below the Short Point Property.

The evidence does not support a finding that the Nortons ever routinely used the portion of the Beach that lies between the two Job's Neck Ponds (below the Short Point Property). Also, because of the conflicting testimony of the Nortons as to whether the Norton family congregated at the beach area below Big Job's Neck Pond (almost a quarter mile in length) or below Little Job's Neck Pond (almost 750 feet in length) the evidence was insufficient to demonstrate where on this long expanse of Beach the family "substantially confined" its activities, let alone that the activities consistently and regularly occurred over the entire Job's Neck Section of the Beach.

Finally, once Allen and Wilda's families moved from central Edgartown to Oyster Pond after Sonny's death in 1981, the Nortons shifted their regular Sunday gatherings to the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach. Thereafter, the Nortons only occasionally used the Job's Neck Section for beach activities. [Note 26] I find that Plaintiffs' occasional beach activities in the Job's Neck Section after 1981 are thus insufficient to create any prescriptive rights therein.

Consequently, given the contradictory testimony as to where within the Job's Neck Section the Nortons regularly concentrated their beach activities between 1958 and 1981, and given the further testimony that the Nortons shifted their regular beach activities to the Oyster Pond Section after Sonny's death in 1981, I find that Plaintiffs have not met their burden to demonstrate that they substantially confined their beach use to any particular part of the Job's Neck Section of the Beach for any twenty-year period between 1958 and 1999. Accordingly, Plaintiffs have failed to establish any prescriptive rights to use the Job's Neck section of the Beach.

Use of the Center Section

The trial evidence demonstrates that from 1938 forward, the Nortons' use of the Center Section of the Beach primarily consisted of occasional walks, shell or driftwood gathering, clamming, surfcasting and fishing, horseback riding, and Jeep or "beach buggy" riding. No witness testified to ever using the Center Section for beach activities like swimming, sunbathing, or picnicking. Rather, the evidence indicates that the Nortons' most common use of the Center Section from 1938 to 1999 consisted of occasional beach rides for pleasure, often incidental to their Sunday gatherings at one of the other Beach sections. [Note 27]

The limited testimony as to surfcasting from the Center Section did not establish that use as a routine or regular activity, nor identify where within the three-quarters of a mile long stretch of the Center Section, this activity would usually occur. Moreover, while recreational in nature, horseback riding and driving a Jeep or "beach buggy" on the beach are not traditional "beach activities." [Note 28] And there is little or no evidence substantiating that any such activities occurring on the Center Section were "'confined substantially' to a regular or particular route or part of the locus." See Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 46. To the extent the Nortons wish to establish a prescriptive right of passage on the Beach, there was no evidence that the Nortons followed any regular path or route when horseback riding or when riding on the Beach in a Jeep or beach buggy. And the Nortons' repeated assertions that they always used the "whole" or "entire" Beach indicate that there was no regular route or area to which the use was confined. Stone, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 267 ("'Passing over a tract of land in various directions at different times from year to year not only has no tendency to establish a right over a particular route, but would seem to be inconsistent with such a claim.'" (quoting Hoyt v. Kennedy, 170 Mass. 54 , 56-57 (1898)). Plaintiffs "may not claim a right to pass generally over a premises 'wherever it is most convenient to themselves

.'" Id. (quoting Jones v. Percival, 5 Pick. 485 , 486 (1827)).

Accordingly, I find that Plaintiffs have failed to establish that any prescriptive rights to use the Center Section of the Beach arose from their activities in that area between 1938 and 1999.

Use of the Oyster Pond Section

As discussed above, if, as Plaintiffs claim, the Norton family's adverse beach use commenced in 1938, [Note 29] the lack of regular use of any part of the Beach between 1956 and 1958 prevented a prescriptive easement from accruing to Plaintiffs during this initial twenty-year time span. Plaintiffs did not present sufficient evidence of Norton family members making regular beach use of the Oyster Pond Section during the two-year period from 1956 to 1958. [Note 30] Allen was stationed in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from 1956 to 1958, during which time he and his future wife, Judy, visited the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach, on only two occasions when Allen came home on leave. [Note 31] The generalized acknowledgments by Flynn family members that they observed either Frank or Sonny taking a catboat down through Oyster Pond to fish near the Oyster Pond Section do not assist Plaintiffs because they were not pegged to any specific time frame or location. [Note 32] They also fall far short of demonstrating a consistent, regular pattern of beach use on this Section of the Beach. Thus, Plaintiffs were unable to show continuous and uninterrupted use of the Oyster Pond Section during the twenty-year period prior to 1958.

The Nortons fare no better in establishing their continuous beach use of the Oyster Pond Section between the time Allen returned from Cuba in 1958 and Sonny's death in 1981. As discussed above, between 1958 and 1981, the Nortons primarily gathered in the Job's Neck Section (approximately 75-80% of summer Sundays), using the Oyster Pond Section only 3-4 Sundays of each summer (approximately 20-25% of summer Sundays). [Note 33], [Note 34] These limited and sporadic uses, even though acknowledged by Flynn family members, do not constitute "continuous" use for purposes of establishing a prescriptive easement over the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach during this time frame. See Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 841 (noting that "plaintiff was required to show more than a collective but individually sporadic" use of the disputed area); see also Boothroyd, 678 Mass. App. Ct. at 46.

It was only following Sonny Norton's death in 1981, and the moves of Allen's family and Wilda's family to certain of the upland Norton Properties shortly thereafter, that the Nortons' routine Sunday beach gatherings shifted from the Job's Neck Section to the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach. [Note 35] The Nortons regularly gathered on the west side of the cut to the ocean in the Oyster Pond Section from 1981 forward. However, this period falls short of the twenty-years needed to perfect a prescriptive easement prior to the Flynns' posting of the Notice to Prevent Easement in 1999. So, in order to establish at least twenty years of continuous beach use of the Oyster Pond Section, the Plaintiffs would have to show that the Norton family's use after Sonny's death was a continuation of Sonny's use of that Section of the Beach. "A person claiming title by adverse possession need not personally occupy the land for twenty years. He may rely on the possession of his tenants, whose possession is his own." Lawrence v. Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 426 (2003).

The Plaintiffs did adduce evidence that Sonny Norton's tenants, the Carrolls, used the beach in the Oyster Pond Section almost every "decent" summer day in the fifteen years prior to Sonny's death in 1981 (1966-1981). [Note 36], [Note 37] However, the evidence of the Carrolls' uses of the Beach derived entirely from the admission of a February 5, 2010 deposition of Robert Carroll, and designations and counter-designations from a September 30, 2005 deposition of Robert Carroll lacks clarity, details, and specificity about any regular location within the Oyster Pond Section to which his family substantially confined their beach activities.

For example, several Flynn family members testified that they often gathered on summer Sundays in the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach to the east of the cut running from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pond, and that the Nortons only began to gather to the west of the cut after 1981. Mr. Carroll, however, was not asked and did not offer consistent information as to where his family would gather relative to the cut when his family used the Beach during this time frame. [Note 38] Given the vague and generalized description of the Carrolls' use of the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach, uncorroborated by any witness testimony or other evidence at trial, the court cannot resolve on this trial record whether the Norton family's uses of the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach after 1981 actually continued in substantially the same location as the Carroll's uses before that time.

Moreover, even if the Carrolls' use of the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach as the tenants of Sonny, could be characterized as derivative of Sonny's claim of right (albeit mistaken) to a one-fifth interest in the Beach and, and thus adverse to the Flynns' interests, it is worth noting Robert Carroll's 2005 deposition testimony that he was friendly with several Flynn family members, including Uncle George, and often accompanied the Flynns at the Oyster Pond Section of the Beach. [Note 39] This testimony supports an inference that the Carrolls were the sometime-guests of the Flynns and used the Beach at the Flynns' invitation, or at least with their permission, thus calling into doubt the adverse nature of the Carrolls' use. Were the Carrolls using the Beach under Sonny's claim of right, or were they using the Beach with permission of the owners? Without evidence to demonstrate that the Carrolls used the Beach without permission, the Plaintiffs cannot rely upon the Carrolls' use to establish continuous, uninterrupted and adverse use of the Oyster Pond Section for more than twenty years.

CONCLUSION

Based on my subsidiary findings of fact and the reasonable inferences to be drawn therefrom, and for all the reasons discussed above, I find that Plaintiffs have failed to carry their burden of establishing that their adverse, open, and notorious uses of the Beach continued uninterrupted in any particular or regular location for any twenty-year period between 1938 and 1999. Accordingly, a new judgment shall enter for Defendants.

ANDREW H. COHN [Note 1] as TRUSTEE OF OYSTER POND EP TRUST; RICHARD L. FIREDMAN; ALLEN W. NORTON; JUDITH A. NORTON and MELISSA NORTON VINCENT as TRUSTEES OF THE QUIET OAKS REALTY TRUST; ALBERT WHITE, TONI W. HANOVER, and SHAUNA WHITE SMITH, as TRUSTEES OF THE QUAMPACKY TRUST; MARK B. NORTON; SHAUNA WHITE SMITH; DEBRA WHITE SCOTT; and LISA WHITE v. MICHAEL D. MYEROW, as TRUSTEE OF BOTAR REALTY TRUST, RABOR REALTY TRUST and TAROB REALTY TRUST; JEFFREY FLYNN, PATRICIA POST, and RICHARD B. KEELER, as TRUSTEES OF THE POHOGONOT TRUST; PAMELA KOHLBERG, as TRUSTEE OF THE JOB'S NECK TRUST; ANDREW KOHLBERG, as TRUSTEE OF THE HIGH ROAD TRUST; and SHORT POINT HOLDINGS, LLC [Note 2]

ANDREW H. COHN [Note 1] as TRUSTEE OF OYSTER POND EP TRUST; RICHARD L. FIREDMAN; ALLEN W. NORTON; JUDITH A. NORTON and MELISSA NORTON VINCENT as TRUSTEES OF THE QUIET OAKS REALTY TRUST; ALBERT WHITE, TONI W. HANOVER, and SHAUNA WHITE SMITH, as TRUSTEES OF THE QUAMPACKY TRUST; MARK B. NORTON; SHAUNA WHITE SMITH; DEBRA WHITE SCOTT; and LISA WHITE v. MICHAEL D. MYEROW, as TRUSTEE OF BOTAR REALTY TRUST, RABOR REALTY TRUST and TAROB REALTY TRUST; JEFFREY FLYNN, PATRICIA POST, and RICHARD B. KEELER, as TRUSTEES OF THE POHOGONOT TRUST; PAMELA KOHLBERG, as TRUSTEE OF THE JOB'S NECK TRUST; ANDREW KOHLBERG, as TRUSTEE OF THE HIGH ROAD TRUST; and SHORT POINT HOLDINGS, LLC [Note 2]