Introduction

By Plaintiff's Notice of Voluntary Dismissal vs. William Howes III (Nov. 20, 2015), by Plaintiff's Stipulation of Dismissal vs. All Other Defendants, assented to by all parties (Nov. 20, 2015), and by the Trial Stipulations Between Plaintiff-in-Intervention, John Tracy Wiggin, and Defendants Laurie Snowden Lebel, Douglas Lebel, Kelly Childs Ragucci and James Quirk Jr., as trustees of the above-captioned trusts (the "trustee defendants") (Jul. 29, 2015), all claims but one in this case were resolved, fully and finally, by dismissal with prejudice. The only one remaining is Intervenor-Plaintiff John Tracy Wiggin's claim to a prescriptive easement over the trustee defendants' land in Yarmouth, which was tried before me, jury-waived. I also took a view.

Based on Mr. Wiggin's and the trustee-defendants' stipulations, the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, my observations at the view, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule that Mr. Wiggin has failed to prove the prescriptive easement he alleges, and thus dismiss that claim, in its entirety, with prejudice, ending the case.

Facts and Analysis

These are the facts as I find them after trial, and the legal conclusions that flow from those facts.

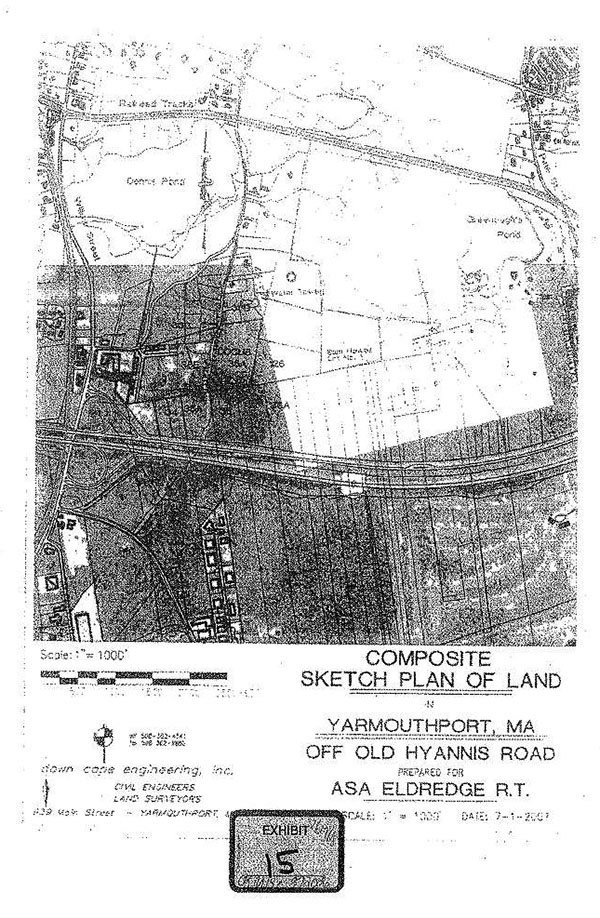

By stipulation, Mr. Wiggin and the trustee defendants agree that the trustee defendants hold title to the so-called Lebel Parcel, [Note 1] approximately eleven acres of undeveloped woodland fronting on Old Hyannis Road in Yarmouthport. [Note 2] The Lebel Parcel lies between the nine acre Wiggin Parcel [Note 3] (also undeveloped woodland) and Old Hyannis Road, and Mr. Wiggin claims a prescriptive easement, appurtenant to the Wiggin Parcel, "in and over a certain cleared strip[,] visible on the ground as of the date of trial[,] that runs [from Old Hyannis Road] through the Lebel Parcel to the Wiggin Parcel (the Disputed Way'), the exact nature and scope of said Disputed Way being in dispute between the parties." [Note 4]

By stipulation, Mr. Wiggin and the trustee defendants also agree that Mr. Wiggin has acquired "at least a partial fractional interest in the Wiggin Parcel

such that he has standing to prosecute his claim of an easement appurtenant to the Wiggin Parcel affecting the Lebel Parcel." [Note 5] They further stipulated that his previous contention that the Disputed Way is a public way was now waived, and that the trial was "strictly on his claim that he holds a prescriptive easement in and over the Disputed Way appurtenant to the Wiggin Parcel." [Note 6]

To establish a prescriptive easement, a claimant must show "the (1) continuous and uninterrupted, (2) open and notorious, and (3) adverse use of another's land (4) for a period of not less than twenty years." White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 413 (2013). See Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007); G.L. c. 187, § 2. The easement is limited to the uses actually made that meet those tests, see Lawless v. Trumbull, 343 Mass. 561 , 562-563 (1962), and to the location and dimensions of those uses. See Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45. The claimant has "the burden of proof on each and every element mentioned above," Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44, and "[i]f any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949). Because "it is contrary to record titles, and begins in disseizin, which ordinarily is wrongful[,] [t]he acts of the wrongdoer [the claimant] are to be construed strictly and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof." Tinker v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74 , 76 (1912) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

The parties do not dispute that the Disputed Way exists on the ground. Where they differ is in its width and, more fundamentally, whether Mr. Wiggin has any appurtenant prescriptive right to use it in its section over the Lebel parcel.

The width of the Disputed Way (which, for reasons that will shortly become apparent, I refer to hereafter as the "path" or "pathway") is not the eight to ten feet claimed by Mr. Wiggin and his witnesses. As convincingly established at trial through the testimony of the trustee-defendants' surveyor, Daniel Ojala, and confirmed by my observations at the view, it is six feet wide. It is a dirt pathway, covered in leaves, with no visible wheel marks or ruts of any kind. It does not follow the contours of the land as is customary of woodland roads [Note 7] but, instead, is unerringly straight. There are no cuts and fills. Rather, the path goes up and down hills, some quite steep, in a straight line without regard to topography. Roots, stumps, and rocks have been left in the path. In the section at issue in this lawsuit, the path currently begins at Old Hyannis Road (a public road) on the west and then proceeds east through the Lebel Parcel, the Wiggin Parcel, and the Boy Scouts' land that abuts Mr. Wiggin's, all of which are undeveloped woodland.

Mr. Wiggin did not create the path or any part of it. Nor, as he conceded at trial, has he ever maintained it in any way, not even to pick up fallen limbs. Rather, the path began as a telephone line easement, granted to the Southern New England Telephone and Telegraph Company by the then-owners of a continuous string of Mid-Cape properties, including the parties' predecessors-in-title, circa 1907. [Note 8] The easement was cut through the woods by the telephone company (thus the path), with poles and wires installed and, presumably, regular inspection and maintenance thereafter using the path. [Note 9] All this explains why the path is straight, regardless of topography, and why it is visible in old aerial photographs yet never appears on any published maps of "ways", public or private. The telephone company abandoned the easement by 1929, [Note 10] however. The poles and wires were removed, and all that remains is the cleared area and a broken insulator, found half-buried in the ground. [Note 11]

The testimony differed on the condition of the path between the time of the easement's abandonment and the present. Ms. Lebel recalls walking in the area in the 1960s and not noticing anything other than narrow, deer-type trails. Mr. Wiggin claims the path was sufficiently wide and well-maintained for him to drive over in his Volkswagen Jetta but, as more fully discussed below, I do not believe him. What I find likeliest is this. The area is heavily forested so that undergrowth has a difficult time getting established and then growing to any size. An airplane crashed in an area accessed by the path in 1979 (the crash site is on the flightpath to Hyannis Airport), and the rescuers used the path to get to the crash, likely brushing it out at that time. The crash site is on the Boy Scouts' land, and the Scouts maintain the trails in and around their property. Once this pathway was widened by the rescuers, the Boy Scouts saw it and thereafter occasionally used a Graveley on the path and removed fallen trees from across it. [Note 12] As previously noted, none of this, nor any maintenance of any kind, has ever been done by Mr. Wiggin nor anyone with an interest in his property. [Note 13] Thus, none of these activities were attributable to him or his land.

I thus turn to those that are.

Mr. Wiggin did not offer evidence of any use of the path by any of his predecessors in title. Indeed, he bought the Wiggin parcel from its prior owner, Edith Carter, for less than $100, strictly as an investment, with no representation it had a right of access to a road, express, implied or prescriptive. That purchase took place under two deeds, the first in 1966 and the second in 1968. [Note 14]

Mr. Wiggin's account begins with his claim that, shortly after purchasing the Wiggin parcel, he drove to where the path intersects with Old Hyannis Road and then drove across the path through the woods in his VW Jetta as far as the Boy Scouts' land. [Note 15] I can believe he drove to the path's intersection at Old Hyannis Road, but I do not believe he drove his car on the path, then or ever. [Note 16] Driving on that part of Old Hyannis Road was difficult from the 1960s through the mid-2000s. Once a main thoroughfare from the north-side communities of the Cape to the south, it became a dead-end when the Mid-Cape Highway (Route 6) was constructed, cutting off its continuation to Hyannis and the other south-side towns. Once cut off, Old Hyannis Road rapidly deteriorated and was a deeply rutted dirt road only 8 feet wide until its widening and paving in 2004. As an isolated dead end, it became a dumping ground for tires, old refrigerators, other broken household appliances, and construction debris, all of which made it even more difficult for driving. Driving the length of the path would have been impossible for a non-high clearance, non-four wheel drive car like the VW Jetta. As previously noted, a witness from the Boy Scouts said that he had traveled on it on a mini-tractor (23hp), and believed a pick-up truck had used it on one occasion. Having seen the narrow, six-foot wide path with its inclines, roots, stumps, and rocks, I am skeptical of the pick-up truck story [Note 17] and, even if true, am not surprised that it was a one-time event. No one with concern for their vehicle's undercarriage would have

driven along it. The trash dumped at its beginning points on Old Hyannis Path would have been a major obstacle just by itself and, of course, the Boy Scouts' installation of cables across the path's entrances in 2002 prevented any vehicular access thereafter. Moreover, the absence of wheel marks and scars on the high roots in the pathway is convincing evidence that the use of the path, by anyone, was pedestrian-only, with the only exception being the Boy Scouts' sporadic Graveley brushing-out and removal of fallen limbs and trees.

Mr. Wiggin admits that he never posted a sign of any type anywhere on the path, not even a directional one at its intersection with Old Hyannis Road (i.e., a sign with his name or the property's address on it, with an indication that the property was down the path). Neither of his deeds contains an easement or reference to an access route, and he was never told of one by his seller. The plan he had done of his property shortly after his purchase does not show any path or road going to or through it. He never built anything on his land (it has always been vacant woodland), and never had a mailbox anywhere on his site or at the intersection of the path with Old Hyannis Road. He claims to have walked along the path to reach his property, but admits that he never did so more than once or twice a year, and not at all from 1995- 2002 when he was living off-Cape. He never walked the path when there was snow on it, which would have shown his footprints. He admits that no one ever saw him, and that he left nothing to indicate that he had ever been there not even a sign on his own land. He never told the owners of the Lebel parcel that he was walking across their land, either orally or in writing. As previously noted, he never made any changes to the path nor did maintenance of any kind not even to remove fallen limbs or trees. Deer leave more evidence of their passing.

Mr. Wiggin has the burden of proving the easement he claims, including its nature and extent. See Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 24 n.1 (2006); Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 629 (1990). He has failed to do so. He did not create the path. He has not changed it in any way. He has never maintained it or left any sign of his claim or passing. Walking along a path in a dense woods, unobserved, once or twice a year (which is all Mr. Wiggin has shown), is not sufficiently actual, open, notorious, or continuous to establish a prescriptive right of use. See Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624 (1992) (acts which are "few, intermittent and equivocal" are insufficient to establish adverse claim); Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 218 (1955) (while record owner's actual knowledge of such use is not required, claimant must show that his acts were such that owner should have known of such use); Phipps

v. Behr, 224 Mass. 342 , 343 (1916) (acts must be sufficiently open and notorious to give "notice to all the world

of an adverse claim of title"); Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 210 (1853) ("[A]cts must not be merely occasional, partial or temporary in their nature."); Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 842 (2008) (intention of claimant "must be manifest by acts of clear and unequivocal character that notice to the owner of the claim might be reasonably inferred").

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, Mr. Wiggin's claim of an appurtenant prescriptive easement over the trustee-defendants' land (the Lebel parcel) is DISMISSED, WITH PREJUDICE. All of Mr. Wiggin's other claims were expressly waived, so they are DISMISSED, WITH PREJUDICE as well. Judgment shall enter accordingly. That judgment shall also reflect that all of the plaintiff's claims were previously voluntarily dismissed, with prejudice, bringing this action to a full and final resolution.

SO ORDERED.

CAPE COD & ISLANDS COUNCIL INC. BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA and JOHN TRACY WIGGIN v. LAURIE SNOWDEN LEBEL, as trustee of the Asa Eldridge Realty Trust, DOUGLAS LEBEL and KELLY CHILDS RAGUCCI as trustees of the Rachel Thacher Lebel Irrevocable Trust 2005, JAMES QUIRK as trustee of the Abegale Snow Lebel College Fund Trust and trustee of the Rebekah Eldred Lebel College Fund Trust, and WILLIAM HOWES III as Public Administrator of the Estate of Asa Eldridge.

CAPE COD & ISLANDS COUNCIL INC. BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA and JOHN TRACY WIGGIN v. LAURIE SNOWDEN LEBEL, as trustee of the Asa Eldridge Realty Trust, DOUGLAS LEBEL and KELLY CHILDS RAGUCCI as trustees of the Rachel Thacher Lebel Irrevocable Trust 2005, JAMES QUIRK as trustee of the Abegale Snow Lebel College Fund Trust and trustee of the Rebekah Eldred Lebel College Fund Trust, and WILLIAM HOWES III as Public Administrator of the Estate of Asa Eldridge.