ALI SHAJII and HALEH AZAR v. MICHAEL D. McDADE

ALI SHAJII and HALEH AZAR v. MICHAEL D. McDADE

MISC 13-480146

October 26, 2017

Middlesex, ss.

CUTLER, C. J.

ALI SHAJII and HALEH AZAR v. MICHAEL D. McDADE

ALI SHAJII and HALEH AZAR v. MICHAEL D. McDADE

CUTLER, C. J.

INTRODUCTION

Plaintiffs Ali Shajii and Haleh Azar own a residential lot in Weston that is burdened by a common driveway easement benefiting the neighboring lot owned by Defendant Michael D. McDade. Starting in 2013, Plaintiffs undertook a major landscape and hardscape improvement project on their lot, which altered the location, dimensions, alignment, and grading of the then-existing driveway easement. On October 21, 2013, while construction of the project was underway, Plaintiffs filed a verified complaint asking this court to declare the easement alterations reasonable, and to enjoin Defendant from overburdening the driveway easement. Defendant counterclaimed for declaratory and injunctive relief relative to the easement alterations made by Plaintiffs.

After obtaining leave of court, Plaintiffs filed a nine-count First Amended Complaint on April 22, 2014. The Amended Complaint seeks injunctive relief to prevent Defendant from overburdening the driveway easement (Count I); seeks declaratory judgments as to the scope of the driveway easement (Count II) and that the driveway easement has been relocated by oral agreement of the parties (Count III); includes an alternative claim for a judicial sanction of the alterations to the driveway easement pursuant to M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 (2004) (Count IV); includes an alternative claim that Defendant is equitably estopped from seeking restoration of the driveway easement to its previous condition (Count V); seeks a declaratory judgment that Plaintiffs have the right to install an automated gate on the driveway easement (Count VI); seeks a declaratory judgment that the Plaintiffs have an express easement right to maintain portions of their septic system on the Defendant's lot (Count VII) or, in the alternative, have an implied easement for same (Count VIII); and seeks injunctive relief to prevent Defendant from materially interfering with Plaintiffs' rights to keep portions of their septic system on Defendant's land (Count IX). Defendant filed an Answer to Amended Complaint and Amended Counterclaim on May 2, 2014. The Amended Counterclaim continues to seek declaratory and injunctive relief regarding the driveway easement alterations (Count I) and additionally asserts a claim for trespass for the alleged unlawful encroachment of the leaching field (Count II).

The trial in this matter commenced on November 16, 2015 following a view by the court, and concluded the next day, November 17, 2015. The Parties stipulated to thirty-three (33) agreed facts. A total of forty-two (42) exhibits were admitted into evidence, all but one of which were agreed upon. At trial, four witnesses testified for Plaintiff: Ali Shajii and Haleh Azar; Louis Cintolo, owner of LVC Construction Management and Plaintiffs' construction supervisor; and John Hamel, professional land surveyor and partner at Snelling & Hamel Associates, Inc. One witness testified for Defendant: Michael D. McDade. Pursuant to the Parties' Joint Pretrial Statement, the issues at trial were limited to: (1) whether the Plaintiffs had the right under M.P.M. Builders to unilaterally relocate, reconfigure, and otherwise modify the driveway easement in the manner they did; (2) whether Defendant's use of the driveway easement constitutes an overburdening; and (3) whether the utility easement reserved in Defendant's deed, includes the right to maintain portions of Plaintiffs' septic system, including the leaching field, on Defendant's lot. [Note 1]

Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Rulings of Law were filed together with a Post-Trial Memorandum of Law on February 11, 2016. Defendant filed his Proposed Findings of Fact and Rulings of Law on the same date. The matter was taken under advisement following closing arguments on March 22, 2016. Now, for the reasons set forth below, I find and rule that the alterations that Plaintiffs made to the driveway easement do not satisfy the MPM Builders test; [Note 2] that Defendant has not overburdened the driveway easement; [Note 3] and that maintenance of a leaching field is not within the scope of the reserved utility easement benefitting Plaintiffs' lot. [Note 4] Accordingly, judgment shall enter for Defendant on all of Plaintiffs' tried claims and on Defendant's counterclaims.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Based on the pleadings, the parties' Stipulated Facts, the admitted trial exhibits, the trial testimony, and the court's view, [Note 5] I find the following pertinent facts, reserving certain details for my discussion of specific legal issues:

1. On May 3, 1989, Richard and Mary Robinson, the then-owners of the real property located at 161 Boston Post Road, Weston, MA, obtained an "Approval Not Required" endorsement from the Weston Planning Board on a plan entitled "Plan of Land in Weston, Massachusetts prepared for Richard and Mary Robinson," dated February 24, 1989 (the "1989 Plan"). The 1989 Plan, which was recorded with the Middlesex Registry of Deeds Southern District ("the Registry") as Plan No. 467 of 1989, showed the division of the 6.77 acre Robinson property into two separate house lots, Lot 1 and Lot 2, served by a proposed common driveway.

2. As shown on the 1989 Plan, Lot 1 is 3.31 acres in size and has 257.55 feet of frontage on Boston Post Road. The 1989 Plan depicts the Robinsons' existing single-family house and subordinate structures, including a barn, on Lot 1, and identifies the street address as 161 Boston Post Road. As shown on the 1989 Plan, Lot 2 is 3.46 acres in size with 168.33 feet of frontage on Boston Post Road. Said Plan depicts a proposed house to be constructed on Lot 2.

3. Subsequent to the endorsement and recording of the 1989 Plan, the Robinsons constructed a new single family house on Lot 2. Originally designated as 161 NW Boston Post Road, the street address of the house on Lot 2 later became 165 Boston Post Road. The Robinsons continued to own both Lot 1 and Lot 2.

4. Plaintiffs, Ali Shajii and Haleh Azar, reside at and are the present record owners as tenants by the entirety of Lot 2, located at 165 Boston Post Road.

5. Defendant, Michael D. McDade, resides at and is the present record owner of Lot 1, located at 161 Boston Post Road.

6. The 1989 Plan depicts a "Proposed Common Driveway" providing shared access to Lot 1 and Lot 2, extending through both Lots in a generally northerly direction from Lot 1's Boston Post Road frontage to the rear boundary of Lot 2 where it ends at the abutting land then owned and operated as a quarry by Robinson's company, the Massachusetts Broken Stone Company. [Note 6]

7. On December 20, 2001, Robinson's Massachusetts Broken Stone Company conveyed the quarry land to BP Weston Quarry LLC, c/o Boston Properties, Inc., for commercial development (the "Quarry-BP Property").

8. Simultaneously with the conveyance of the quarry land, BP Weston Quarry, LLC granted two easements to Robinson for ingress and egress over the Quarry-BP Property to Boston Post Road, for the benefit of Lot 1 and Lot 2 as shown on the 1989 Plan. Access Easement A is a 30-ft. wide area running from the end of the Proposed Common Driveway at the rear lot line of Lot 2 to a second easement identified as Access Easement B. Access Easement B connects Access Easement A to Boston Post Road. The instrument granting the two easements to Robinson is entitled "Grant of Easement" and is recorded with the Registry at Book 34371, Page 139 (the "BP Access Easement").

9. Under the express terms of the BP Access Easement, the two granted easements "shall be limited to, and shall be used by the Grantee and his successors and assigns, for use in connection with one (1) single-family residence on each of 'Grantees' Benefitted Parcels' [Lot 1 and Lot 2] for ingress and egress by the owners, tenants or occupants thereof and their respective contractors, subcontractors, tradesmen, visitors, employees and invitees to the extent consistent with a single family residential character and nature of each of Grantee's Benefitted Parcels."

10. The BP Access Easement also recites that the "easements, restrictions, covenants and conditions set forth herein shall be binding upon and inure to the benefit of the Grantor and the Grantee and their successors and assigns and are intended to be appurtenant to and run with each of the Grantees' Benefitted parcels ."

11. On March 30, 2007, the executor of the Estate of Richard Robinson conveyed Lot 1 (hereinafter also referred to as the "McDade Property") to the defendant, Michael D. McDade, by deed recorded with the Registry at Book 49221, Page 248 (the "McDade Deed").

12. The McDade Deed granted Lot 1 together with the right to pass and repass

over the portion of the existing driveway on Lot 2 shown on a sketch plan as 'Granted Easement Area' for the purpose of ingress and egress only, by motor vehicle only, over the abutting BP Quarry, LLC property to Boston Post Road subject to the [terms of the BP Access Easement] provided, however, that the foregoing easement shall not be used as a primary means of access for Lot 1 to Boston Post Road. [Emphasis added.]

13. The McDade Deed provides that "Grantor and grantee shall share evenly in the reasonable cost associated with repair and maintenance of Grantee's Easement Area including repaving and removal of snow and ice."

14. Although a sketch plan was referenced in the McDade Deed, no plan showing the "Granted Easement Area" was actually attached to or recorded with the McDade Deed, and neither party has located the referenced sketch plan. The Parties agree, however, that the easement granted is coterminous with the driveway shown on a survey plan drawn by Snelling & Hamel Associates, entitled "Site Plan 165 Boston Post Road Weston, Massachusetts" and last revised April 15, 2013, admitted at trial as Exhibit 6, which shall hereinafter be referred to as the "Driveway Easement."

15. Under the terms of the McDade Deed, the Grantor retained a right and easement appurtenant to Lot 2 in and on the Proposed Common Driveway or such other area as Grantor and Grantee may reasonably agree upon (the "Shared Driveway") for purposes of ingress and egress on foot and in motor vehicles between Boston Post Road and Lot 2.

16. The McDade Deed referred to a May 30, 2007 Driveway Agreement between McDade and the Estate of Richard Robinson, which granted McDade the right, at his expense and subject to approval by the owner of Lot 2, to construct a driveway on Lot 2 for direct access to Boston Post Road to serve the residence on Lot 2 (the "Driveway Agreement"). [Note 7]

17. As provided in the McDade Deed, upon completion of a driveway for Lot 2 pursuant to the Driveway Agreement, the "Shared Driveway" easement reserved for the benefit of Lot 2 over the McDade Property would terminate. [Note 8]

18. On January 11, 2008 the executor of the Estate of Richard Robinson conveyed Lot 2 on the 1989 Plan (hereinafter the "Shajii/Azar Property") to the Plaintiffs Ali Shajii and Haleh Azar by deed recorded with the Registry at Book 50598, Page 303 (the "Shajii/Azar Deed").

19. The Shajii/Azar Deed conveyed Lot 2 "subject to the right of the owner of Lot 1 shown on the [1989 Plan] to pass and repass over the premises for access via the BP Weston Quarry property to Boston Post Road pursuant to [the McDade Deed] ."

Defendant's Use of the Driveway Easement

20. Between 2009 and the end of 2010, the Quarry-BP Property was commercially developed, and the BP Access Easement was improved from Boston Post Road to the northerly boundary line of Lot 2 where it connects to the Driveway Easement.

21. Since his purchase of Lot 1 in 2007, Defendant has used the Driveway Easement for access to and from his Lot with his personal vehicles, including passenger cars, his personal truck, work trucks, trailers, and other motor vehicles. He also allows guests and people working on his property to use the Driveway Easement for access to Lot 1. Personal delivery vehicles (e.g., UPS, FedEx, etc.) also use the Driveway Easement to access Lot 1.

22. McDade prefers to use the Driveway Easement particularly when using his trailers or plow attachments because it can be difficult to exit onto Boston Post Road from Lot 1's front driveway.

23. Lot 1 also has a driveway entrance through its frontage on Boston Post Road (a/k/a Route 20). The driveway entrance is directly in front of the house and is quite visible from the street. It appears from the street to be the sole access into the property. There are no signs posted at the entrance indicating that visitors should not enter or that an alternative driveway access is available.

24. McDade has installed a plastic, mesh, spring-loaded "kiddie gate" at the entrance to the Lot 1 front driveway to protect his children when they are playing in the front of the house. The kiddie gate is easily retractable.

25. Prior to bringing their Complaint in this action, Plaintiffs never complained to McDade about his use of the Driveway Easement.

Plaintiffs' Alterations to the Driveway Easement [Note 9]

26. In May of 2013, Plaintiffs commenced construction of substantial landscape and hardscape improvements to the area in front of their house, including the area through which the Driveway Easement is located (the "Project"). At a cost of almost $450,000, the Project included extensive re-grading, planting, paving, and the construction of a circular drive of stone pavers surrounding a 16-foot diameter centerpiece fountain and bordered on one side with a stone retaining wall.

27. The Project resulted in significant changes to the location, alignment, grades, paving and width of the Driveway.

28. A site plan prepared by Snelling & Hamel Associates, Inc., last revised on April 15, 2013, shows the Driveway Easement, as it existed prior to the alterations undertaken by Plaintiffs (the "Existing Conditions Plan").

29. Before the alterations, the Driveway Easement was generally straight and obstacle-free. Its paved width varied between 17.5 and 20 feet throughout. The pavement width exceeded 19 feet at each end, where the Driveway Easement connected to the Lot 1 driveway on the south and to the BP Access Easement on the north.

30. Before the alterations, the southern third section of the Driveway Easement gradually sloped downward from the Lot 1 driveway toward the central section of the Easement in front of the Plaintiffs' house. From there the pitch became steeper so that as it approached the Quarry-BP Property in the northern third section, the pitch was approximately 11%.

31. Before the alterations, the Driveway Easement connected directly to the paved driveway area at the entrance to the barn on Lot 1.

32. The Project significantly altered the dimensions, location, alignment and physical conditions of the Driveway Easement as follows:

a. The Project relocates the Driveway Easement approximately 34 feet to the east of its original point of connection with the Lot 1 driveway area in front of the barn, and at an elevation that is approximately 5 feet higher than the Lot 1 driveway, thereby completely disconnecting the Driveway Easement from the Lot 1 driveway.

b. The Project physically blocks off the original connection between the Lot 1 driveway and the Driveway Easement by planting a row of trees and installing a line of large boulders, as well as an added berm that is a few feet high. (See Ex. 37.)

c. The Project reduces the width of the Driveway Easement at the point of connection with Lot 1 to approximately 10.5 feet -- nearly half of its original width of 19 feet.

d. Instead of the relatively flat paved connection from Lot 1 to the original Driveway Easement, the relocated Driveway Easement can only be accessed from Lot 1 over an unpaved portion of Lot 1 and onto a steep 10.5% slope on Lot 2.

e. In the area in front of Plaintiffs' house, the Project replaces the relatively straight alignment of the Driveway Easement with a 60± diameter circular driveway, encircling an approximately 16-foot diameter fountain, and bordered with a stone retaining wall on its eastern side. The newly-constructed circular Driveway path is approximately 22 feet in width as it passes around the fountain.

f. The Project reduces the width of the northern third section of the Driveway Easement from approximately 17.5 feet to 15.5 feet at its narrowest point.

g. Where once there were no physical impediments to access between the Driveway Easement and the BP Access Easement, the Plaintiffs have installed and propose to maintain control of a new electronic gate. Defendant would only be able to enter the gate by using a transponder in his vehicle. The installation of the electronic gate at the point of entrance to the BP Access Easement further narrows the width in this section to less than 12 feet.

33. The Plaintiffs never obtained permission from the Defendant to make any of the above described alterations to the Driveway Easement, or to otherwise alter said Easement.

34. The Project did not include any work on Lot 1 to accommodate the relocation and change in elevation of the Driveway Easement.

35. Since the Project completely blocks off and disconnects the Lot 1 driveway from the Driveway Easement, Defendant can only gain access from the paved driveway in front of his barn to the newly located Driveway Easement by traversing an unpaved berm, approximately 30 feet away from and five feet higher than, that paved driveway area.

36. Based on his own construction experience, Defendant estimates that it would cost him in the neighborhood of $45,000 - $75,000 to create a proper driveway connection from his barn to the relocated Driveway Easement.

37. The alterations to the Driveway Easement from the Project make it difficult to navigate vehicles with an attached trailer or plow through the gate, over the Driveway Easement and onto Lot 1.

The Leaching Field

38. In the McDade Deed, the grantor expressly reserved "a right and easement as appurtenant to and for the benefit of Lot 2 in and over Lot 1 for a utility easement for any existing utilities serving Lot 2 including the maintenance, repair and/or replacement of such utilities." (The "Utility Easement").

39. The Azar/Shajii Deed conveyed Lot 2 "with the benefit of [a] utility easement pursuant to [the McDade Deed] ."

40. A portion of the leaching field and a connecting pipe serving the septic system for Lot 2 currently encroaches on Lot 1. [Note 10]

41. Defendant was not aware of the encroachment until after this action was commenced.

DISCUSSION

This action originated with Plaintiffs' attempt to obtain the court's sanction for the changes they made to the location and design of the right of way easement across their lot (Lot 2), which had been granted in the McDade Deed for the benefit of Lot 1. The physical changes in grade, location, pavement materials, alignment, and width of the original driveway were the result of an elaborate landscaping improvement plan that Plaintiffs proceeded to execute on Lot 2 without first coming to any agreement with the dominant estate owner, Defendant McDade. The Plaintiffs seek, among other forms of relief, a declaration that, consistent with the holdings in M.P.M. Builders, and Martin v. Simmons Properties, LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 10 (2014), they had the right as the servient estate holders to make all of the changes resulting from their Project.

In M.P.M. Builders, the Supreme Judicial Court recognized the right of a servient estate owner to make any and all beneficial uses of his land consistent with an easement, including the right to "'make reasonable changes in the location or dimensions of an easement, at the servient owner's expense, to permit normal use or development of the servient estate, but only if the changes do not (a) significantly lessen the utility of the easement, (b) increase the burdens on the owner of the easement in its use and enjoyment, or (c) frustrate the purpose for which the easement was created.'" Id. at 90 (quoting Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 4.8(3) (2000)). The SJC subsequently explained that "[t]he owner of a servient estate over which an easement for passage runs may not make 'any change in its grade or surface, which makes the way less convenient and useful to any appreciable extent to anyone who has an equal right in the way.'" Martin, 467 Mass. at 20 (quoting Killion v. Kelley, 120 Mass. 47 , 52 (1876)).

Scope and Purpose of the Driveway Easement

Here, the purpose of the Driveway Easement was set forth unambiguously at the time of its creation; namely, the Driveway Easement was granted

for the purpose of ingress and egress only, by motor vehicle only, over the abutting BP Weston Quarry LLC property to Boston Post Road provided, however, that the foregoing easement shall not be used as a primary means of access from Lot 1 to Boston Post Road. [Emphasis added.]

However, the precise dimensions, physical attributes, and location of the granted easement are left unstated in the McDade Deed. Despite the express mention in the McDade Deed of an attached "sketch plan" locating the Driveway Easement, no sketch plan was recorded with the Deed, and neither Party has been able to produce one, if it ever existed. The lack of a written description or plan is no impediment, however, because "[w]here the instrument creating an easement does not fix its location or bounds, a court may do so in the absence of agreement by the parties." Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 533 (2012).

Here, the parties have agreed that the Existing Conditions Plan, last revised in 2013, accurately reflects the Driveway Easement's dimensions, alignment, location, and grades on the ground before Plaintiffs commenced their Project. The trial record also reflects that the Driveway Easement existed in that same location and state since McDade acquired Lot 1 in 2007, when the Easement was first created. Thus, as the Existing Conditions Plan is the best (and only) evidence of the dimensions, alignment, location, grading and other physical attributes of the Driveway Easement intended by the grantor and grantee, I find and rule that the Driveway Easement reserved in the McDade Deed extended northerly through Lot 2 over the paved driveway area on the north side of the barn on Lot 1 to the BP Access Easement area on the Quarry-BP Property at Lot 2's northern boundary, as shown on the Existing Conditions Plan. As shown, it is:

* approximately 19 feet in width, permitting the passage of two cars side-by-side;

* relatively straight and obstacle-free;

* connected with Lot 1 as a continuation of a paved driveway area on the north side of the barn where its entrance doors are located;

* relatively flat in grade where it connects with the paved driveway on Lot 1; and

* paved with bituminous concrete throughout.

Alterations to the Driveway Easement

In connection with the Project, Plaintiffs significantly and unilaterally altered the above-described location, alignment, grading, width and other physical conditions of the Driveway Easement contemplated when the Easement was created. Of particular import to the court's inquiry, Plaintiffs

* added a roundabout circular drive with a center fountain;

* reduced the width of the portion of the driveway connecting to Lot 1 to only 10.5 feet (nearly half of the original width);

* increased the slope of the southern third of the driveway from a "relatively flat" slope to one with a steep grade of 10.5%;

* completely disconnected the Driveway Easement from the Lot 1 driveway by relocating the original point of connection with Lot 1 approximately 34 feet to the east of, and approximately 5 feet higher than, the Lot 1 driveway outside Defendant's barn; and

* added a limited access, electronic gate at the boundary with the BP Access Easement, which physically constricts the connection between the Driveway Easement and the BP Access Easement to a width of less than 12 feet. [Note 11]

On the evidence before me, I find and rule that the alterations made to the Driveway Easement as a result of the Project are, cumulatively, unreasonable. By completely disconnecting the Driveway Easement from the driveway on Lot 1, by narrowing the width, steepening the grade, realigning the relatively straight driveway into a circular one with the added physical obstacles of a fountain and retaining wall, and by installing a narrow, electronic entrance gate, Plaintiffs have significantly lessened the utility of the Driveway Easement as originally contemplated, increased the burdens on Defendant's use and enjoyment of the Driveway Easement, and frustrated the Driveway Easement's purpose of connecting Lot 1 with the BP Access Easement. Accordingly, the changes are not consistent with the standards set forth in MPM Builders and Martin.

Relocating the Driveway Easement away from Defendant's barn entrance and paved driveway area has significantly lessened the utility and increased the burden on Defendant's use. Prior to the Project alterations, Defendant accessed the Driveway Easement over an approximately 19-foot wide, relatively flat, paved driveway directly from the entrance to his barn. He could then progress downhill, past Plaintiffs' house, along a straight, 17-19 foot wide route to the BP Access Easement, and thence out to Boston Post Road. Post-Project, Defendant can no longer enter the Driveway Easement directly from the paved driveway in front of his barn. Instead, he must navigate his vehicles from the paved area to the top of a grassy bank in order to reach the new Driveway Easement location, 34 feet northeast of the original connection. [Note 12] Once there, the entrance to the Driveway Easement is via a 10.5 foot wide, steep slope of 10.5%, constricted on one side by trees and on the other by a stone retaining wall, before navigating half-way around the circular drive to reach the remainder of the Driveway Easement. [Note 13] That remaining northern third section of the Driveway Easement has also been narrowed from approximately 19 feet in width to approximately 12 feet where the newly-installed electric gate is located at the entrance to the BP Access Easement. [Note 14]

Finally, the addition of an access control gate at the entrance to the BP Access Easement would also increase the burden and inconvenience to Defendant, as well as his shared maintenance obligations and costs. Defendant, his family, guests, caretakers, vendors, delivery drivers, service providers, etc., would all be unable to access Defendant's property through the Driveway Easement without one of the transponders. [Note 15] Requiring Defendant to submit to this level of control and restricted access unreasonably and materially interferes with the exercise of his ingress and egress rights over the Driveway Easement to reach the BP Access Easement and eventually Boston Post Road, particularly where Plaintiffs have not demonstrated a need for the gate. [Note 16] Cf. Stucchi v. Colonna, 9 Mass. App. Ct. 851 , 851 (1980) (in determining whether a servient owner can place a gate on a right of way, "the question is '(w)hat is reasonable in the use of the property of the respective parties'" (quoting Blais v. Clare, 207 Mass. 67 , 69-70 (1910))); see also Wile v. Rattigan, 16 LCR 764 , 768 (2008) (Miscellaneous Case No. 304412) (Long, J.) (ordering a servient owner to remove a gate erected over a right of way where the dominant owner was unreasonably inconvenienced and the servient owner obtained little benefit).

Taken together, I find that the collective effect of alterations resulting from the Project are unreasonable under the standards set forth in M.P.M. Builders and Martin. In M.P.M. Builders the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) specified how a servient lot owner should proceed when he wishes to make changes to an easement. The SJC wrote:

Clearly, the best course is for the [owners] to agree to alterations that would accommodate both parties' use of their respective properties to the fullest extent possible." Roaring Fork Club, L.P. v. St. Jude's Co., [36 P.3d 1229, 1237 (Colo. 2001)]. In some cases, the parties will be unable to reach a meeting of the minds on the location of an easement. In the absence of agreement between the owners of the dominant and servient estates concerning the relocation of an easement, the servient estate owner should seek a declaration from the court that the proposed changes meet the criteria in § 4.8(3). See id. at 12371238. Such an action gives the servient owner an opportunity to demonstrate that relocation comports with the Restatement requirements and the dominant owner an opportunity to demonstrate that the proposed alterations will cause damage. Id. at 1238. The servient owner may not resort to self-help remedies, see id. at 1237 (after failing to reach agreement with easement holder, servient owner went forward with construction), and, as M.P.M. did here, should obtain a declaratory judgment before making any alterations.

M.P.M. Builders, 442 Mass. at 93 (2004) [emphases added]. In contrast, Plaintiffs filed their Verified Complaint on October 21, 2013, five months after they unilaterally began construction on the Driveway Easement. Plaintiffs had already completed a substantial amount of work by the time they sought a declaration from this court. Plaintiffs have defied the recommendations of the SJC in the M.P.M. Builders decision, yet invoke that decision's protections for their actionsfinding it more palatable to ask for forgiveness than for permission.

In light of my findings, I rule that Plaintiffs' claims under Counts IV and VI fail and Defendant prevails on his Count I Counterclaim. Accordingly, a declaratory judgment shall enter in accordance with this decision.

Overburdening of the Driveway Easement

Plaintiffs claim that Defendant overburdens the Driveway Easement by using it as "primary means of access" to his property, which is prohibited under the terms of the McDade Deed. McDade counters that he does not use the Driveway Easement as his primary means of access.

Overburdening of an easement generally occurs when the use "exceeds the scope of rights held under an easement." Southwick v. Planning Bd. of Plymouth, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 315 , 319 & n.12 (2005). That is, the easement is used "for a purpose different from that intended in the creation of the easement" or "overly frequent or intensive use," sometimes identified as a "nuisance." Id. The party asserting the benefit of an easement has the burden of proving its existence, nature, and extent. Martin, 467 Mass. at 10; Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 24 & n.1 (2006) (quoting Levy v. Reardon, 43 Mass. App. Ct. 431 , 434 (1997)). In determining the scope of an easement, the court looks "'to the intention of the parties regarding [its] creation, determined from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or which they are chargeable to determine the existence and attributes of a right of way.'" Martin, 467 Mass. at 14 (quoting Adams v. Planning Bd. of Westwood, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 389 (2005)). "In interpreting a deed, we seek, insofar as established rules of construction permit, 'to give effect to the intent of the parties manifested by the words used.'" Lindsay v. Board of Appeals of Milton, 362 Mass. 126 , 131 (1972) (quoting Walker v. Sanderson, 348 Mass. 409 , 412 (1965)). When the language is unambiguous, parol evidence may not be used to vary or control its import. It is only where the language is ambiguous that the court looks beyond the face of the deed. Hamouda, 66 Mass. App. Ct. at 25 (quoting Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. 526 , 528 (1851)). The language of a deed is ambiguous where "its meaning is uncertain and susceptible of multiple interpretations." Here, the meaning of the phrase "primary means of access," although disputed by the Parties, is not ambiguous. [Note 17] Under ordinary common usage, "primary" is understood to connote that something is of first or highest importance; it is also understood to mean "fundamental or basic." [Note 18]

Applying the ordinary meaning of "primary," I find that the grantor intended that the front access driveway should be the main, chief, or principal access to Lot 1, and that the Driveway Easement should be the "secondary," or subordinate access. Bearing this interpretation in mind, the evidence does not support a finding that Defendant uses the Driveway Easement as a primary access to Lot 1. Although Azar testified that Defendant's use of the Driveway Easement increased to as much as "3-4 times per day" on a "near daily basis" after the BP Access Easement was improved and the signalized intersection was added in 2010, Plaintiffs had no contemporaneous written or photographic documentation of Defendant's use of the Driveway Easement. Additionally, Plaintiffs' testimony concerning excessive use of the Driveway Easement by delivery truck drivers, and by Defendant's guests, caretakers, service vendors, and employees, similarly lacked evidentiary support. [Note 19] Nor did Plaintiffs have evidence of Defendant's use of his front driveway, comparatively speaking. And both Plaintiffs admit that they work full-time jobs that, with limited exception, keep them away from their home during the day. [Note 20] Given Plaintiffs' limited opportunities to observe Defendant's use of the Driveway Easement as compared to his front driveway use, I cannot infer on the basis of the unspecific and uncorroborated testimony before me that Defendant uses the Driveway Easement as a primary means of access to Lot 1. [Note 21]

This is not to say there are no limits on Defendant's use; rather, the volume, frequency, and intensity of Defendant's use of the Driveway Easement must be commensurate with its use as a secondary means of access to his residential lot. [Note 22] But this also does not mean that Defendant's use is limited to private, low-volume, uses by the residents, as Plaintiffs contend. Occasional deliveries and use by family, guests, vendors, etc. is within reason, and thus permissible. Defendant may also use the Driveway Easement when travelling with an attached trailer or plow when it is safer to do so, so long as such use is kept to a reasonable volume. At the same time, it is not reasonable for Defendant to bar or obstruct his front driveway entrance, preventing or actively deterring people from accessing his lot that way. [Note 23] Although there is no evidence in this case that it has occurred, it would not be reasonable for Defendant to instruct or encourage his family, guests, or invitees to use the Driveway Easement exclusively, or to permit such use on a nearly continuous basis. See, e.g., Rendell, 17 LCR at 746 (Misc. Case. No. 05- 308443) (Long, J.), 2009 WL 4441212, at *17 ("A constant stream of traffic over a way that was intended to be used as a back entrance unreasonably interferes with the plaintiffs' enjoyment of their property.").

On the weight of the evidence, I cannot find that Defendant has overburdened the Driveway Easement by using it as a primary means of access to Lot 1. Accordingly, judgment shall enter against Plaintiffs, and for Defendant on Counts I and II of the Amended Complaint.

The Leaching Field and Utility Easement

During the course of the Project construction and this ensuing litigation, Defendant discovered that Plaintiffs' septic leaching field encroaches on Lot 1. Defendant claims that Plaintiffs have no right to maintain the encroachment, and ask the court to order its removal. Plaintiffs counter that the leaching field existed at the time the ownership of Lots 1 and 2 was severed in 2007, and was consequently included within the scope of the Utility Easement reserved in the McDade Deed. Plaintiffs here bear the burden of proving the nature and extent of the Utility Easement. See, Martin, 467 Mass. at 10.

When the executor of the Robinson estate conveyed out Lot 1 to McDade, the estate retained ownership of Lot 2, and expressly reserved to itself "a utility easement for any existing utilities serving Lot 2 including the maintenance, repair and/or replacement of such utilities ." The McDade Deed does not, however, identify the particular utilities which were then existing, does not define the term "utilities," does not identify the locations of the then-existing utilities serving Lot 2, and does not include any mention of a septic system or a leaching field. Although the term "utilities" is left undefined in the McDade Deed, the term is not ambiguous.

The ordinary and approved dictionary definition of the term "utility" is "b (1): a service (as light, power, or water) provided by a public utility (2): equipment or a piece of equipment to provide such service or a comparable service." Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Ed. (2014). Defendant argues that this ends the inquiry, as a private sewage disposal system with its attendant leaching field is not such a service. Plaintiff, on the other hand, cites Robinson v. Board of Health of Chatham, 58 Mass. App. Ct. 394 , 396-400 (2003), for the proposition that a private septic system constitutes a utility.

I do not find the Robinson case either dispositive or useful here, however. Robinson is not as broad as Plaintiffs assert, and Plaintiffs have identified no case law that recognizes the leaching field component of a private, on-site sanitary sewage disposal system as a utility, or as ordinarily being within the scope of a general utility easement. In Robinson, the Appeals Court held that G.L. c. 187, § 5 the statute permitting abutters to a private way to install pipes and other appurtenances necessary for the transmission of gas, electricity, telephone, water and sewer service includes the right to install private "septic/sewage pipes (leading from a septic tank to a distribution box and leaching field) under the private way." Id. at 394-95. Although the Appeals Court focused on (and then rejected the relevance of) the distinction between public sewer lines and private septic system pipes, the court did not, in so ruling, consider or interpret the term "utilities" as including private septic systems. Further, the instant dispute over whether a leaching field is a "utility" under the terms of an express easement affecting a private lot, plainly does not involve permissible uses within a private way under G.L. c. 187, § 5, or pipes or other appurtenances used for transmission of services. A leaching field is of a categorically different nature as it does not serve to transmit wastewater; rather its essential function is to receive and absorb the effluent from a private septic tank. [Note 24]

Moreover, even if the term "existing utilities" as used in the McDade Deed could be regarded as ambiguous, such that the court could consider extrinsic evidence of the grantor's intent in light of the circumstances surrounding the McDade Deed, Plaintiffs have produced no evidence of the grantor's intent, and in particular that he intended that the reserved utility easement would include an existing leaching field. [Note 25] Indeed, no evidence was submitted to suggest that the grantor was even aware that the leaching field for the Lot 2 septic system extended into Lot 1. Accordingly, I find and rule that the expressly reserved Utility Easement over Lot 1 does not encompass the leaching field serving Lot 2. Finally, although Plaintiffs have not pressed either contention at trial, I note that under the circumstances presented by this case, an easement for the leaching field cannot be implied, [Note 26] nor could the encroachment be excused as de minimis. [Note 27]

For these reasons, I find that Plaintiffs' maintenance and use of all or a portion of their leaching field on Lot 1 constitutes a continuing trespass. Consequently, Defendant is entitled to judgment in his favor under Count II of the Amended Counterclaim and Count VII of the First Amended Complaint, declaring that a portion of the Plaintiffs' leaching field unlawfully encroaches upon Defendant's Lot 1, and enjoining Plaintiffs from continuing to direct wastewater and effluent from their septic system into the portion of the leaching field which encroaches on Lot 1.

CONCLUSION

Based upon the facts I have found, and for the reasons described herein, I find that Defendant is entitled to judgment in his favor on all of the claims and counterclaims tried. Judgment is to enter consistent with this Decision. However, before judgment enters, I will afford counsel for the Parties an opportunity to confer about the form of the court's judgment, so as to address appropriate matters that might affect the timing and manner in which the Driveway Easement restoration, and discontinuation of the leaching field encroachment is to take place. Therefore, counsel shall confer and, within sixty (60) days, submit an agreed upon form of proposed judgment, including, but not limited to, the parameters and timing for the proposed restoration of the Driveway Easement and discontinuance of the encroaching leaching field. Alternatively, if the parties cannot agree on a form of proposed judgment, the court will proceed to enter judgment consistent with this Decision, which will, at a minimum, include orders requiring restoration of the southern section of the original Driveway Easement (including its original connection with Lot 1); requiring removal of the electronic access gate and attendant structural components from the northern end of Driveway Easement; requiring removal of the fountain from the center section of the Driveway Easement; and enjoining Plaintiffs from continuing to use the portion of the Lot 2 leaching field which encroaches on Lot 1. [Note 28]

exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Plaintiffs did not pursue their claims under Count III (declaration that the parties mutually agreed to the relocation of the driveway easement), Count V (judgment that Defendant is estopped due to prior statements regarding driveway alterations), Count VIII (judgment that implied easement exists for septic leaching field), and Count IX (judgment that Defendant materially interfered with leaching field by installing structures). They are deemed waived.

[Note 2] Plaintiffs' Amended Complaint Counts IV and VI, and Defendant's Amended Counterclaim Count I.

[Note 3] Plaintiffs' Amended Complaint Counts I and II.

[Note 4] Plaintiffs' Amended Complaint Count VII and Defendant's Amended Counterclaim Count II.

[Note 5] "[T]hough a view is not evidence in the technical sense, it has been said that it inevitably has the effect of evidence and information properly acquired upon a view may properly be treated as evidence in the case." Berlandi v. Commonwealth, 314 Mass. 424 , 450-51 (1942).

[Note 6] The 1989 Plan shows the Proposed Common Driveway running in a northerly direction on the east side of the house and barn on Lot 1, then widening into an area behind the barn before splitting into two forks just before crossing into Lot 2. The westerly fork, labelled "drive," ends at the proposed house site on Lot 2. The easterly fork continues through Lot 2 in a northerly direction, on the east side of the proposed house site, to the quarry land at the northern boundary of Lot 2. It is the easterly fork which is at issue in this case.

[Note 7] The Driveway Agreement is recorded with the Registry at Book 49221, Page 250.

[Note 8] This condition was eventually met and the parties do not have any disputes in this case involving the Driveway Agreement.

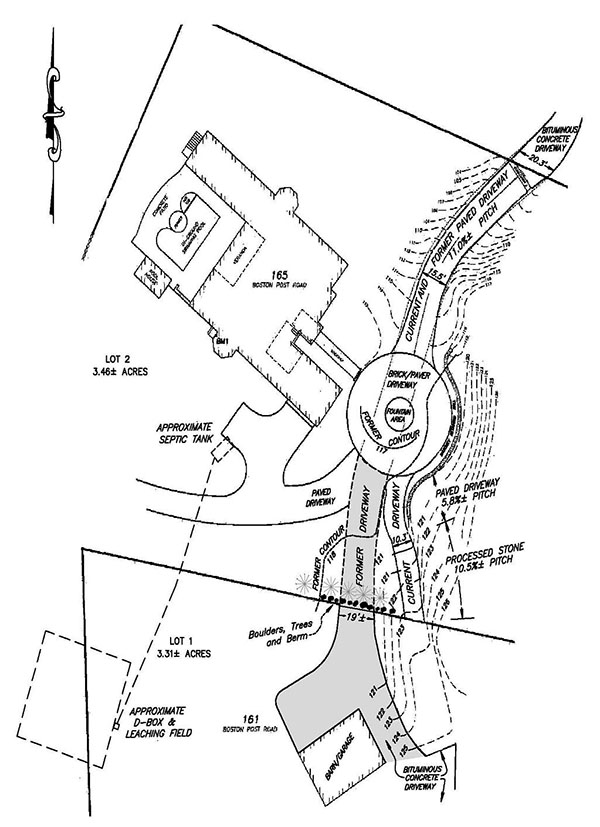

[Note 9] The Driveway Easement in its pre-alteration and post-alteration condition is depicted in the attached Decision Sketch, as adapted from Trial Exhibit 41 and based on the court's view.

[Note 10] The attached Decision Sketch depicts the location of the leaching field.

[Note 11] At the view, I observed that, although not impossible, driving through the narrow gate opening could be difficult for a large SUV or a truck, or for a passenger vehicle towing a trailer.

[Note 12] Defendant estimates the cost to pave this new connection area to be from $45,000 to $75,000.

[Note 13] At the view, I observed that maneuvering could foreseeably be made more difficult when adding rain, ice, and snow to the equation, or if cars are parked in the circular driveway.

[Note 14] The maintenance costs Defendant must bear, particularly for the safe removal of ice and snow, would also increase from these cumulative changes. See, e.g., Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 4.8, Illustration 5 (2000).

[Note 15] Defendant and his visitors, of course, could use the front entrance to Defendant's property, but the availability of this alternative means of access has no bearing on whether or not the addition of an electronic access control gate would substantially interfere with Defendant's rightful uses of the Driveway Easement.

[Note 16] Plaintiffs have not substantiated Azar's assertion at trial that trespassers routinely enter the property.

[Note 17] Indeed, the term "primary access" is employed (without definition or explanation) by the Massachusetts Appellate Courts to describe the main or principal route of travel to and from a development or place. See, e.g. Rettig v. Planning Board of Rowley, 332 Mass. 476 , 478, 481 (1955); Wall Street Development Corporation v. Planning Board of Westwood, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 844 , 848 (2008); Town of Dover v. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority, 414 Mass. 274 , 277 (1993).

[Note 18] See, e.g., Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Ed. (2014) defining the adjective "primary" as "

2 a: of first rank, importance, or value: PRINCIPAL

[Note 19] Plaintiffs also complain that Defendant runs his business, Galaxy Integrated Technologies, Inc. ('Galaxy") an electronic security company out of his home, allowing Galaxy's trucks to use the Driveway Easement. They introduced photographs showing Galaxy trucks parked on Defendant's property. However, Defendant's testimony satisfactorily explained these occurrences some being incidental to installation of electronic security equipment on his own property, and the others involving use by Defendant's personal maintenance crew of an "old" vehicle that Galaxy no longer uses. I do not find these uses to have exceeded the scope of the Driveway Easement.

[Note 20] Azar testified that she is away from her home, working, between 40 and 60 hours per week, and Shajii similarly testified that he is not at home on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays between the hours of 8:00 AM and 6:00 PM, or on Wednesdays between the hours of 8:00 AM and 3:00 PM.

[Note 21] For certain of his larger vehicles, particularly those towing trailers or with attached plows, Defendant admits that he favors using the signalized intersection for safer egress rather than using his front driveway, which opens to the roadway after a blind curve. This is a reasonable use of the Driveway Easement, consistent with it being a secondary form of access to his lot.

[Note 22] See a similar analysis concerning primary and secondary access routes in Rendell v. Massachusetts Dep't of Conservation & Recreation, 17 LCR 734 , 746 & n.15 (2009) (Misc. Case. No. 05-308443) (Long, J.), 2009 WL 4441212, at *17 aff'd, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 1138 (2012) (Rule 1:28 Decision).

[Note 23] Defendant at times has used a retractable mesh "kiddie gate" across his front driveway. Although this may only be a "temporary" structure, and can be manually retracted, this visible obstruction no doubt discourages visitors and invitees from using the front driveway to access Defendant's lot. Defendant may continue to use this mesh "kiddie gate" only for its intended purpose of safeguarding his driveway and yard when his children, pets, etc., are using the front yard. But he must take care to retract the gate when front yard activities have ended.

[Note 24] 313 Code Mass. Regs. § 11.03 defines a "leaching field" as "a soil absorption system" as defined in the State Environmental Code, Title 5. Under Title 5, 310 Code Mass. Regs. § 15.002, the many components of an On-site Sewage Treatment and Disposal System are defined and described. A "Soil Absorption System" is defined as "[a] system of trenches, galleries, chambers, pits, field(s) or bed(s) together with effluent distribution lines and aggregate which receives effluent from a septic tank or treatment system" [emphasis added]. The regulations make clear distinctions between those components of an On-site Sewage Treatment and Disposal System that are involved in the collection, distribution, and conveyance of wastewater and effluent (structural), and the soil absorption system itself, which "is not a structural component." Ultimately, Title 5 defines a "Sanitary Sewer" as "[a]ny system of pipes, conduits, pumping stations, force mains and all other structures and devices used for collecting and conveying wastewater to a public or private treatment works," [emphasis added], thereby excluding a leaching field from the definition.

[Note 25] Both Lots 1 and 2 contain multiple acres. There is no evidence that a suitable location for a leaching field cannot be found within the boundaries of Plaintiffs' own lot.

[Note 26] See Zotos v. Armstrong, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 654 , 657 (2005) (rejecting implied easement theory where the deed contains express easements) (citing Joyce v. Devaney, 322 Mass. 544 , 549-50 (1948)).

[Note 27] See Goulding v. Cook, 422 Mass. 276 , 279-80 (1996) (expressly holding that an encroaching septic leaching field is not minimal, and must be enjoined as a trespass).

[Note 28] The Parties, of course, are free to reach an alternative agreement and settlement of their claims before judgment enters.