MILDRED KNEER as trustee of The Kneer Family Revocable Trust v. ROBERT LUCIANO, MICHAEL KULESZA, CHRISTOPHER WIDER and DONALD HANSSEN as members of the Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, and THOMAS MURRAY.

MILDRED KNEER as trustee of The Kneer Family Revocable Trust v. ROBERT LUCIANO, MICHAEL KULESZA, CHRISTOPHER WIDER and DONALD HANSSEN as members of the Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, and THOMAS MURRAY.

MISC 14-486294

May 5, 2017

Norfolk, ss.

LONG, J.

DECISION

Introduction

At issue in this G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal is whether a vacant dimensionally nonconforming parcel of land on Hunter Avenue in Norfolk has merged for zoning purposes with an adjacent property, rendering the vacant parcel separately unbuildable. Mildred Kneer and her daughter Deirdre Mead, as trustees of The Kneer Family Revocable Trust, are the record owners of that vacant parcel. Ms. Mead also owns the adjacent property at 11 Hunter Avenue in her individual name, which already has a house on it. If the two are merged for zoning purposes, a second house cannot be built.

Ms. Mead prepared a building permit application to construct a single family home on the vacant parcel, which she had her mother, Ms. Kneer, sign. The town's building commissioner denied that application on the ground that the undersized vacant parcel is in common control with 11 Hunter Avenue, the two have thus merged for zoning purposes, and the vacant lot is therefore not a separately buildable lot. The Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals subsequently denied the appeal of that denial, and this case is the appeal of the Board's decision.

The owner of the abutting property at 7 Hunter Avenue, Thomas Murray, intervened in this action and, like the zoning board, contends that the vacant parcel is not eligible for a building permit because Ms. Mead controls both that parcel and her adjacent property at 11 Hunter Avenue. Ms. Kneer (Ms. Mead's co-trustee, in whose name this case was brought) disagrees that the properties have merged and argues that the property is grandfathered and buildable. [Note 1]

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule that the trust confers on Ms. Mead, as trustee, such broad powers over the trusts' real estate that she effectively has legal control over the trust's parcel, and that because she also has legal control over her contiguous property at 11 Hunter Avenue, the properties have merged for zoning purposes. The trust's parcel is thus not separately buildable, and I affirm the Board's decision.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

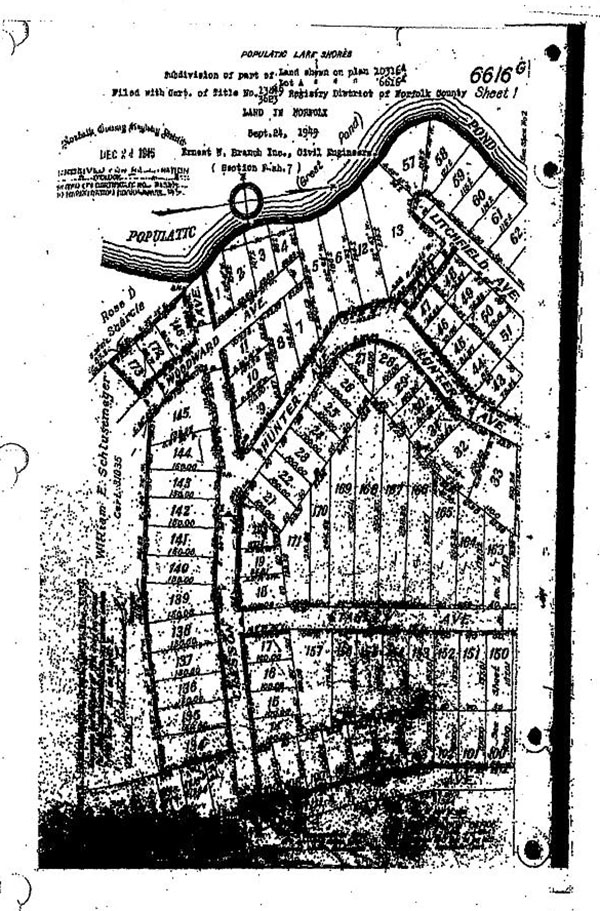

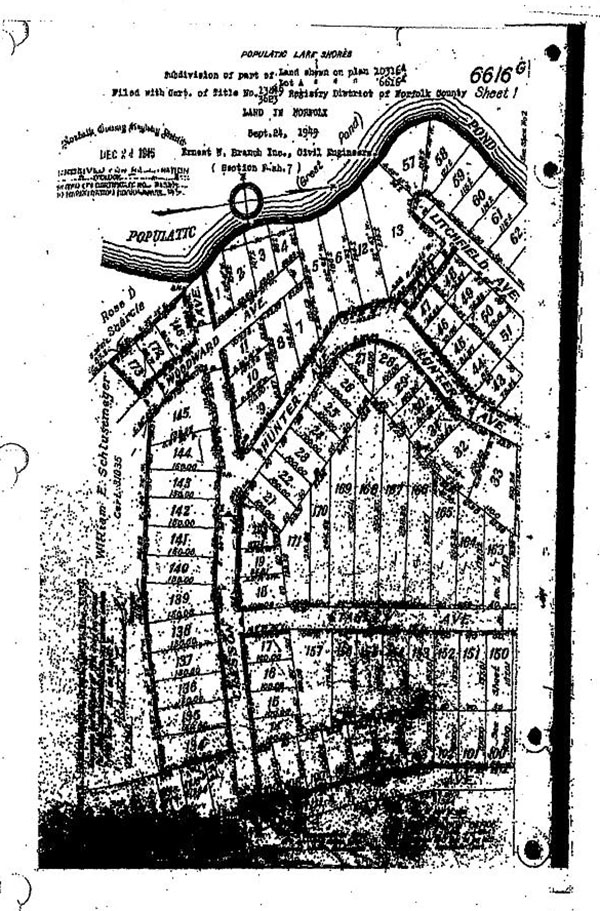

The Hunter Avenue Properties

On September 21, 1978, Andrew and Deirdre Mead purchased two parcels of registered land in Norfolk: the house and property at 16 Hunter Avenue (Lots 29, 30 and 31 on Land Court Plan 6616-G, filed at the Registry on December 24, 1945) and the unimproved land across the street at 11 Hunter Avenue (Lots 44 and 45 on Land Court Plan 6616-G). [Note 2] See Exhibit 1, attached hereto. The Meads used 16 Hunter Avenue as a starter home. After having children, in the late 1980s they built a larger colonial-style house on 11 Hunter Avenue for their expanding family. They and their three sons moved into the 11 Hunter Avenue house in 1988, and they sold 16 Hunter Avenue house to Ms. Mead's sister Diane Gates (who has since moved to North Carolina). In December 1988, Ms. Mead conveyed her in interest in 11 Hunter Avenue to Mr. Mead. The Meads divorced in 2003, and title to 11 Hunter Avenue remained in Mr. Mead's name until April 29, 2011 when he conveyed the property back to Ms. Mead, purportedly pursuant to the terms of their divorce.

Ms. Mead has lived at 11 Hunter Avenue since 1988. Her two youngest sons, Daniel and Dustin, presently reside there with her. Mr. Mead is often at the property as well, for he and Ms. Mead have reconciled. Their oldest son, Douglas, moved out of the house after he married in 2011, but he and his wife, whose parents live near Ms. Mead, would like to move back to the neighborhood.

11 Hunter Avenue is contiguous to a vacant, dimensionally nonconforming parcel of registered land shown as Lots 46 and 47 on Land Court Plan 6616-G. Lots 46 and 47, individually and in combination, have failed to satisfy the minimum lot size requirement since before Norfolk adopted its zoning bylaw in 1953. The 1953 bylaw, however, "grandfathered" Lots 46 and 47 (hereinafter the "Trust Parcel"), which have since merged into a single lot for zoning purposes. See Memorandum and Order on the Parties' Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment (Aug. 21, 2015) at 8 & 11. As further discussed below, however, the Trust Parcel has now lost whatever grandfather protection it might have had as a separately buildable lot because it has merged with the adjacent 11 Hunter Avenue property.

In 2002, the town advertised Lots 46 and 47 (today the Trust Parcel) for sale at an auction. [Note 3] Mr. and Ms. Mead attended the auction with their son, Douglas, [Note 4] who was interested in buying and potentially building a house on the property. Their neighbor Thomas Murray, the interventor-defendant in this case, attended the auction as well. Mr. Murray owns the property at 7 Hunter Avenue (Lots 6, 12, and 13 on Land Court Plan 6616-G), which is next door to the Trust Parcel. [Note 5] He has lived there for over twenty years, and he and his wife Wendy value its private wooded location. Mr. Murray wanted to purchase the Trust Parcel at the auction to help maintain the privacy of his home.

The Meads outbid Mr. Murray, and the town conveyed the Trust Parcel to Douglas for $40,000 on July 15, 2002. Douglas borrowed the purchase funds from his then-uncle, Richard "Lindsay" Drisko, who was at that time married to Ms. Mead's sister Deborah Drisko (they later divorced in 2012). On April 4, 2003, Douglas conveyed the Trust Parcel to Mr. Drisko for one dollar, but Douglas still hoped to one day build a home on the property.

On September 24, 2012, Mr. Drisko conveyed the Trust Parcel to Ms. Mead and Ms. Mead's mother, Ms. Kneer, as trustees of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust, for $50,000. Ms. Kneer wanted to help sever Mr. Drisko's ties to the property because he and her daughter were divorcing. Ms. Kneer also considered that there might come a time when she would want to live near Ms. Mead. She did not, however, conduct any investigation as to whether the property was buildable. As further discussed below, because Ms. Mead acquired legal control of the Trust Parcel as a result of the September 24, 2012 conveyance, and because at that time she also had such control over her contiguous property at 11 Hunter Avenue, those properties have merged for zoning purposes and, thus, the Trust Parcel is not separately buildable.

Ms. Mead's Powers as Trustee

Ms. Kneer and her late husband William Kneer established The Kneer Family Revocable Trust on November 6, 2001. That trust has been amended twice, first by a Restatement dated May 24, 2010 (the "Restatement"), and then by a Second Amendment dated August 19, 2015. Mr. and Ms. Kneer were the initial beneficiaries and trustees of the trust and, in the event they both died or ceased to act as trustees, the initial trust named their daughter, Diane Gates, as their successor trustee. [Note 6]

After Mr. Kneer passed away in March 2010, Ms. Kneer and Ms. Mead executed the May 24, 2010 Restatement that amended the trust. Since then, both Ms. Kneer and Ms. Mead have been the trustees. The Restatement names Ms. Mead, Ms. Gates, and Ms.

Drisko, jointly, or their survivor, as Ms. Kneer's successor trustee in the event of her incapacity or death. Restatement §§ 3.02(b); 3.03(a). Under the Restatement, Ms. Kneer is the sole beneficiary and, after her death, the trust property is to be distributed into separate trusts for each of her children.

When the trust acquired the Trust Parcel on September 24, 2012, the Restatement was in effect and Ms. Mead was a trustee of the trust. As further discussed, the trust confers on each trustee such extensive powers over trust property that Ms. Mead has had legal control over Lots 46 and 47 (the Trust Parcel) since the trust acquired it.

As amended, the trust is revocable by Ms. Kneer until her death, at which time it will be irrevocable. Restatement §§ 1.04(b); 5.01. Ms. Kneer has the right to "remove any Trustee [Note 7] with or without cause at any time," Restatement § 3.02(a), and, in the event of her incapacity or death, Mr. Borchers, as the designated Trust Advisor, may remove any trustee. Restatement § 3.10(g). The Restatement also provides that Ms. Kneer "reserve[s] the absolute right to review and change my Trustee's investment decisions." Restatement § 1.04(e). Importantly, though, the Restatement immediately goes on to state "however, my Trustee is not required to seek my approval before making investment decisions," Id., and authorizes each trustee to make those decisions "in the manner my Trustee determines to be in the best interests of the beneficiaries," and may do so without prior approval from any court. Restatement § 12.01. There is no provision that requires the trustees to act jointly. [Note 8]

Article 12 of the Restatement confers on each trustee broad authority to manage and control trust property. [Note 9] In particular, Restatement § 12.18 specifically grants each trustee extensive powers over trust real estate [Note 10]:

My Trustee may sell at public or private sale, convey, purchase, exchange, lease for any period, mortgage, manage, alter, improve and in general deal in and with real property in such manner and on such terms and conditions as my Trustee deems appropriate.

My Trustee may grant or release easements in or over, subdivide, partition, develop, raze improvements, and abandon any real property.

My Trustee may manage real estate in any manner that my Trustee deems best and may exercise all other real estate powers necessary to effectuate this purpose.

My Trustee may enter into contracts to sell real estate. My Trustee may enter into leases and grant options to lease trust property even though the term of the agreement extends beyond the termination of any trusts established under this agreement and beyond the period that is required for an interest created under this agreement to vest in order to be valid under the rule against perpetuities. My Trustee may enter into any contracts, covenants, and warranty agreements that my Trustee deems appropriate.

Restatement § 12.11 provides that "[m]y Trustee may encumber any trust property by mortgages, pledges, or otherwise, and may negotiate, refinance, or enter into any mortgage or other secured or unsecured financial arrangement, whether as a mortgagee or mortgagor . . . ." Under Restatement § 12.20, "[m]y Trustee may abandon any property that my Trustee deems to be of insignificant value." The trustees each also have broad contract powers:

My Trustee may sell at public or private sale, transfer, exchange for other property, and otherwise dispose of trust property for consideration and upon terms and conditions that my Trustee deems advisable. My Trustee may grant options of any duration for sales, exchanges, or transfers of trust property. My Trustee may enter into contracts, and may deliver deeds or other instruments, that my Trustee deems appropriate.

Restatement § 12.06. Restatement § 12.02 further provides,"[m]y Trustee may execute and deliver any and all instruments in writing that my Trustee considers necessary to carry out any of the powers granted in" the trust. [Note 11]

The Building Permit Application and the Appeal to the Board

After the trust acquired the Trust Parcel, Ms. Mead made arrangements to obtain septic and building permits for the construction of a new house on the property. Ms. Mead discussed the requirements for a septic permit with the board of health and made arrangements with an engineer to submit a report in support of a septic permit application. Ms. Mead then completed the application for the septic permit, had Ms. Kneer sign the application, and submitted it to the board of health. On July 10, 2013, the board of health issued a disposal system construction permit to the Kneer Family Revocable Trust for the construction of a septic system for a three bedroom dwelling unit on the Trust Parcel.

Ms. Mead thereafter completed an application for a building permit dated December 1, 2013 and, again, had Ms. Kneer sign it. The application proposes the construction of a single-family, three-bedroom, Cape-style dwelling with 1,200 square feet of gross living area. [Note 12] Ms. Mead never discussed the details of the proposed house with Ms. Kneer. The application provides that the estimated total project cost is $100,000. [Note 13] Ms. Mead obtained all of the estimates necessary to complete the application. The application includes a good standing approval form signed by the tax collector and town clerk, whose signatures Ms. Mead obtained. Ms. Mead submitted the application and designated herself and Mr. Mead as the contact persons for the application. In accordance with this instruction, the town's building commissioner subsequently reached out to Ms. Mead for further information regarding the application, which she provided. Ms. Kneer has never had any contact with the building commissioner regarding the application.

On April 8, 2014, the town's building commissioner denied the building permit application on the grounds that the property does not satisfy current zoning requirements (it is undersized), and was no longer grandfathered as a separate buildable lot because it is effectively held in common with 11 Hunter Avenue and thus merged. The building commissioner addressed his letter denying the application to Mr. and Ms. Mead, Kneer Family Revocable Trust, at Ms. Kneer's Medfield address.

The building commissioner's denial was appealed to the zoning board. Ms. Mead completed the application for hearing, and, again, had Ms. Kneer sign it. Ms. Mead made the presentations at the Board hearings regarding the appeal. Ms. Kneer did not participate in those presentations.

In a decision filed with the town clerk on September 3, 2014, the Board denied the appeal from the building commissioner's building permit denial. This case is a G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal of the Board's decision.

Further relevant facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

In this G. L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal, as in all such proceedings, the reviewing court makes de novo factual findings based solely on the evidence admitted in court, and then, based on those facts, determines the legal validity of the Board's decision with no evidentiary weight given to any findings by the Board. Shirley Wayside Ltd. P'ship v. Bd. of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 474-475 (2012); Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc. v. Bd. of Appeal of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381382 (2009); Roberts v. Sw. Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 485-486 (1999). The Board's decision "'cannot be disturbed unless it is based on a legally untenable ground' or is based on an 'unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary' exercise of its judgment in applying land use regulation to the facts as found by the judge." [Note 14] Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc., 454 Mass. at 381382 (quoting Roberts, 429 Mass. at 487). The dispositive issue before the court is whether the Trust Parcel has merged with the contiguous property at 11 Hunter Avenue for zoning purposes, thus rendering the Trust Parcel separately unbuildable. Because I find that those properties have merged, I affirm the Board's decision.

"A basic purpose of the zoning laws is 'to foster the creation of conforming lots.'" Asack, 47 Mass. App. Ct. at 736 (quoting Murphy v. Kotlik, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 410 , 414 n.7 (1993)). To this end, the doctrine of merger [Note 15] provides that "'adjacent lots in common ownership will normally be treated as a single lot for zoning purposes so as to minimize nonconformities.'" [Note 16] Preston v. Bd. of Appeals of Hull, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 236 , 238 (2001) (quoting Seltzer v. Board of Appeals of Orleans, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 521 , 522 (1987)). It is well settled that "a landowner will not be permitted to create a dimensional nonconformity if he could have used his adjoining land to avoid or diminish the nonconformity." Planning Bd. of Norwell v. Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 689 , 690 (1989), S.C., 406 Mass. 1008 (1990). See Carabetta, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 268.

Once merger occurs, it cannot be undone. "A person owning adjoining record lots may not artificially divide them so as to restore old record boundaries to obtain a grandfather nonconforming exemption; to preserve the exemption the lots must retain 'a separate identity.'" Asack, 47 Mass. App. Ct. at 736 (quoting Lindsay v. Board of Appeals of Milton, 362 Mass. 126 , 132 (1972)).

The owners of the properties at issue are nominally different: Ms. Mead and Ms. Kneer as trustees of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust are the record owners of the Trust Parcel, and Ms. Mead owns the adjoining property at 11 Hunter Avenue. But common ownership for purposes of merger, however, is determined not by "the form of ownership, but [by] control." Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 691 (lot held by landowners as individuals merged with adjoining lot held by same landowners as trustees). Whether properties have merged is thus governed by this inquiry: "did the landowner have it 'within his power', i.e., within his legal control, to use the adjoining land so as to avoid or reduce the nonconformity?" Id.

This case thus turns on whether Ms. Mead has had legal control over both properties. I find that she has had such control since September 24, 2012 when the trust acquired the Trust Parcel. [Note 17] As the owner of 11 Hunter Avenue, there is no question Ms. Mead has legal control over that property. Because she owns the Trust Parcel as trustee of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust, her control over the Trust Parcel depends on her powers as a trustee of that trust.

"The interpretation of a written trust is a matter of law to be resolved by the court. The rules of construction of a contract apply similarly to trusts; where the language of a trust is clear, we look only to that plain language." Ferri v. Powell-Ferri, 476 Mass. 651 , SJC-12070, slip op. at 3 (March 20, 2017) (internal citation omitted). The court first looks to "'the language of the contract by itself, independent of extrinsic evidence concerning the drafting history or the intention of the parties'" to determine whether there is ambiguity. Id. (quoting Bank v. Thermo Elemental Inc., 451 Mass. 638 , 648 (2008)). "Language is ambiguous 'where the phraseology can support a reasonable difference of opinion as to the meaning of the words employed and the obligations undertaken.'" Ferri, slip op. at 3 (quoting Bank, 451 Mass. at 648). If the court determines that the contract language is ambiguous, the court may consider extrinsic evidence "'to remove or to explain the existing uncertainty or ambiguity,'" however, "'extrinsic evidence cannot be used to contradict or change the written terms.'" Ferri, slip op. at 3 (quoting General Convention of the New Jerusalem in the U.S. of Am., Inc. v. MacKenzie, 449 Mass. 832 , 836 (2007)). The court's objective is "to discern the settlor's intent from the trust instrument as a whole and from the circumstances known to the settlor at the time the instrument was executed." Ferri, slip op. at 3 (citing Hillman v. Hillman, 433 Mass. 590 , 593 (2001)).

The language of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust, as restated and amended, clearly and unambiguously confers on Ms. Mead as trustee legal control over all of the trust's real estate, including the Trust Parcel. [Note 18] Restatement § 12.18 grants each trustee sweeping authority to "deal in and with real property in such manner and on such terms and conditions as my Trustee deems appropriate" and to "manage real estate in any manner that my Trustee deems best and . . . exercise all other real estate powers necessary to effectuate this purpose." Restatement § 12.18 further authorizes each trustee to, inter alia, "sell . . . , convey, purchase, exchange, lease . . . , mortgage, manage, alter, [and] improve" and to "grant or release easements in or over, subdivide, partition, develop, raze improvements, and abandon" the trust's real property. [Note 19] Under Restatement § 12.02,"[m]y Trustee may execute and deliver any and all instruments in writing that my Trustee considers necessary to carry out any of the powers granted in" the trust. The trust's clear language gives each trustee complete discretion to exercise such powers.

I do not agree with Ms. Kneer's argument that the trust either does not authorize Ms. Mead to act alone or that it is ambiguous as to whether Ms. Mead may do so. Ms. Kneer contends that the terms "my Trustee" and "Trustee," which are used to describe the trustees' powers, are unclear and could be read to require Ms. Mead to obtain her mother's assent to exercise her trustee powers. I disagree. Under Restatement § 13.06(t), "[t]he term 'my Trustee' or 'Trustee' refers to the initial Trustees named in Article One [Ms. Mead and Ms. Kneer] and to any successor . . . ." The terms "my Trustee" and "Trustee" thus include Ms. Mead. The trust explicitly authorizes each trustee to make investment decisions without the approval of Ms. Kneer. Restatement § 1.04(e). There is no provision that requires Ms. Mead to obtain Ms. Kneer's consent to exercise her trustee powers, nor is there any provision that requires the trustees to act together. It is thus clear that each trustee has authority to act alone. Ms. Kneer may review or change a trustee's investment decisions, she may remove a trustee with or without cause, and she may even revoke the trust, but she cannot prevent Ms. Mead from exercising her trustee powers in the first instance.

Moreover, Ms. Mead in fact has exercised legal control over the Trust Parcel. [Note 20] She pursued the septic and building permits, investigated what was necessary to obtain those permits, made arrangements with at least one professional to support the permit applications, obtained estimates for the proposed construction, completed the permit applications, submitted those applications, communicated with town officials regarding the applications, received and responded to inquiries from town officials about the

applications, prepared the appeal of the building commissioner's denial of the building permit, and presented at the Board's hearings. [Note 21] Ms. Kneer did nothing more than sign the applications when Ms. Mead asked her to do so. Ms. Mead effectively exercised control over the entire permit application process and, under the trust, had the right to do so. As trustee, she has complete authority to manage the trust's real property, including the Trust Parcel, in whatever way she deems appropriate.

I also am not persuaded by Ms. Kneer's argument that Ms. Mead does not have "legal" control over the Trust Parcel because, she claims, Ms. Mead would violate her fiduciary duty if she transferred the property without Ms. Kneer's consent because Ms. Kneer wants to live there. First, I am not persuaded this is so. Second, even assuming that this would be a breach of Ms. Mead's fiduciary duty, that would not preclude Ms. Mead from taking such action. The trust grants her the power to take the actions she took, and makes those actions binding on the trust, regardless of whatever consequences Ms. Mead might later face from Ms. Kneer.

Ms. Mead thus has legal control over the Trust Parcel. She acquired that control on September 24, 2012, at which time she also had legal control over her contiguous property at 11 Hunter Avenue. The properties therefore merged for zoning purposes on that date. See Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 691. The Trust Parcel is not separately buildable, and Ms. Kneer is not entitled to a building permit for the construction of a house on that property.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Board's decision denying the appeal of the denial of a building permit to construct a single family house on the Trust Parcel is AFFIRMED and Ms. Kneer's claims are DISMISSED, with prejudice. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] I previously ruled on summary judgment that Norfolk's 1953 zoning bylaw grandfathered the trust's property at issue. The sole issue at trial was thus whether merger occurred, terminating those grandfathered protections.

[Note 2] The vacant property in dispute is shown as Lots 46 and 47 on that plan. Intervenor-defendant Thomas Murray owns Lots 6, 12, and 13.

[Note 3] The record is not entirely clear on how the town came to have title to the lots but it appears it was through a tax taking. The source of the town's title is not material to the case.

[Note 4] Hereinafter I refer to Douglas Mead as Douglas solely for purposes of clarity because he shares a last name with his father.

[Note 5] Land Court Plan 6616-G depicts a twenty-foot wide path between Mr. Murray's property and the Trust Parcel, but there is no such designated area on the property.

[Note 6] The initial trust named their daughter Ms. Drisko as Ms. Gate's successor trustee, their daughter Ms. Mead as Ms. Drisko's successor trustee, and their attorney, Timothy Borchers, Esq., as Ms. Mead's successor trustee.

[Note 7] Section 13.06(t) of the Restatement provides:

[t]he term 'my Trustee' or 'Trustee' refers to the initial Trustees named in Article One and to any successor, substitute, replacement, or additional person, corporation, or other entity that is from time to time acting as the Trustee of any trust created under the terms of this agreement. The term 'Trustee' refers to singular or plural as the context may require.

Article One names Ms. Mead and Ms. Kneer as the initial Trustees.

[Note 8] For example, Ms. Kneer, as one of the trustees of the trust, brought this action without including her co-trustee, Ms. Mead.

[Note 9] Article 12 also provides the trustees with extensive powers regarding investments, banking, trust businesses, insurance, contracts, loans and borrowing, and a number of other matters.

[Note 10] Ms. Mead and Ms. Kneer acknowledged their broad powers over trust real estate in two registered Certificates of Trust, both of which they each signed under the pains and penalties of perjury. A Certificate of Trust dated September 28, 2012 and registered on October 1, 2012 provides that "[t]he trustees, pursuant to the provision of said trust, have authority to act with respect to the real estate owned by such trust by the execution of any one trustee acting alone" (emphasis added). It further states:

[t]he trustees, pursuant to the provision of [the] trust, have authority to act with respect to the trust:

a. to amend the trust;

b. to sell the real estate of the trust;

c. to mortgage the real estate of the trust;

d. to lease the real estate of the trust;

e. to convey trust assets to themselves either individually or as principal or trustee of another entity; [and]

f. to declare homestead on trust property on behalf of trust beneficiaries under

M.G.L. ch. 188 and to terminate the same.

A second Certificate of Trust dated January 21, 2016 and subsequently registered contains nearly identical language.

[Note 11] On August 19, 2015, after Ms. Kneer filed this action, she and Ms. Mead executed a Second Amendment that further amended the trust. This Second Amendment is irrelevant to the case because, as discussed more fully below, the merger had previously occurred under the terms of the May 24, 2010 Restatement and, for zoning purposes, once merger occurs it cannot be undone. See Asack v. Bd. of Appeals of Westwood, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 733 , 736 (1999). The Second Amendment provides that after Ms. Kneer's death, Ms. Mead "shall not serve as a trustee of any share for the vacant land owned by me through this trust located in Norfolk, Massachusetts [the Trust Parcel]." Second Amendment § 1.01. Upon Ms. Kneer's death, the Trust Parcel is to be placed in a trust for Ms. Mead's benefit if she is still living unless that will cause the property to merge with Ms. Mead's property, or unless Ms. Kneer has built or commenced building a home on the Trust Parcel. Section 1.02 of the Second Amendment provides:

I give the vacant land owned by me through this trust located in Norfolk, Massachusetts ("my vacant land") [the Trust Parcel] adjoining land of my daughter, Deirdre K. Mead, to a separate trust share for her benefit, if she is then living, on the terms identical to the Inheritance Trust for her hereinbelow, except that there may be no administration of this separate trust share by her or an Interested Trustee, and her sisters, Diane and Deborah, and not Deirdre, will be the Independent Trustees.

But, if Deirdre is not then living, or if I have built a home or have commenced building a home on my vacant land, or if such inheritance in the trust share created under this section shall cause a merger of my vacant land with the land of Deirdre, for local zoning law purposes, as determined in an building permit application and/or final appeal therefrom, then such home and/or my vacant land will become part of my remaining trust property disposed of herein below and shall not fund any such share for Deirdre.

The remaining trust property is to be divided into separate shares in trust for Ms. Kneer's daughters, with one-quarter to Ms. Gates, three-eighths to Ms. Mead, and three-eighths to Ms. Drisko. Second Amendment § 1.02.

[Note 12] The application further provides that the total floor area will be 900 square feet, there will be one fire place, two or three bathrooms, six or seven rooms, two open decks/porches, a forced hot air heating system, and a central air cooling system.

[Note 13] The application also provides that the estimated building cost is $75,000, the estimated electrical cost is $3,000, the estimated plumbing cost is $3,000, the estimated mechanical (HVAC) cost is $10,000, and the estimated mechanical (fire suppression) cost is $2,000.

[Note 14] In determining whether the Board's decision was "based on a legally untenable ground," the court must determine whether it was decided "on a standard, criterion, or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws." Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003) (internal quotations omitted). In determining whether the decision was "unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary," "the question for the court is whether, on the facts the judge has found, any rational board" could come to the same conclusion. See id. at 74.

[Note 15] The doctrine of merger applies to both registered and recorded land. See Williams Bros. Inc. of Marshfield v. Peck, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 682 , 686-688 (2012).

[Note 16] A municipality may, however, adopt a zoning bylaw that protects properties from merger. See Carabetta v. Bd. of Appeals of Truro, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 266 , 269 (2008) (citing Marinelli v. Board of Appeals of Stoughton, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 902 , 903 (2005)). Norfolk's current zoning bylaw does not preclude the application of the merger doctrine in this case. See Memorandum and Order on the Parties' Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment (Aug. 21, 2015) at 7-8.

[Note 17] I am not persuaded by Ms. Kneer's argument that merger should be reserved for circumstances where landowners enter into sham conveyances to avoid zoning requirements. The merger doctrine is often implicated in that situation, but there is no such limitation. I do not agree that the case on which Ms. Kneer relies, Savery v. Duane, 22 LCR 284 (2014) (Piper, J.), imposes one.

[Note 18] Because I reach this conclusion, I need not consider extrinsic evidence regarding the issue. See Ferri, slip op. at 3. I thus consider neither Ms. Kneer's testimony regarding her intent to maintain control over the trust's property, nor the testimony of her attorney, Mr. Borchers, who drafted the trust documents and provided de bene testimony at trial about his and Ms. Kneer's intent with respect to the trust's provisions.

Even if I did consider that testimony, however, I do not believe that Ms. Kneer truly intended to have sole control over the trust's property. If that was her real intention, she would not have added Ms. Mead as a trustee, or she would at least have made sure that the trust included explicit provisions limiting Ms. Mead's authority. Furthermore, Ms. Mead twice certified under the pains and penalties of perjury that each trustee has "authority to act with respect to the real estate owned by such trust by the execution of any one trustee acting alone." See Certificate of Trust dated September 28, 2012 & Certificate of Trust dated January 21, 2016.

[Note 19] Many of these powers are unambiguously set forth in other trust provisions as well. Restatement § 12.11 states, "[m]y Trustee may encumber any trust property by mortgages, pledges, or otherwise, and may negotiate, refinance, or enter into any mortgage or other secured or unsecured financial arrangement, whether as a mortgagee or mortgagor . . . ." Under Restatement § 12.20, "[m]y Trustee may abandon any property that my Trustee deems to be of insignificant value." Also, under Restatement § 12.06:

My Trustee may sell at public or private sale, transfer, exchange for other property, and otherwise dispose of trust property for consideration and upon terms and conditions that my Trustee deems advisable. My Trustee may grant options of any duration for any sales, exchanges, or transfers of trust property. My Trustee may enter into contracts, and may deliver deeds or other instruments, that my Trustee deems appropriate.

Restatement § 12.06.

[Note 20] Ms. Kneer contends that she and Ms. Mead did not believe that Ms. Mead had control over the property, evidenced by the facts that Ms. Mead did not sign the applications at issue and that Ms. Mead once requested Ms. Kneer's permission to have vehicles servicing her septic system drive over the Trust Parcel. I do not believe this contention. Ms. Mead's many, many other actions plainly demonstrate that she in fact exercised control over the property.

[Note 21] I do not believe, as Ms. Kneer argues, that Ms. Mead did all of this simply to help her mother. I find that Ms. Mead was acting in her capacity as trustee.

MILDRED KNEER as trustee of The Kneer Family Revocable Trust v. ROBERT LUCIANO, MICHAEL KULESZA, CHRISTOPHER WIDER and DONALD HANSSEN as members of the Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, and THOMAS MURRAY.

MILDRED KNEER as trustee of The Kneer Family Revocable Trust v. ROBERT LUCIANO, MICHAEL KULESZA, CHRISTOPHER WIDER and DONALD HANSSEN as members of the Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, and THOMAS MURRAY.