The defendant Jay Duca ("Duca") applied to the Chelsea Zoning Board of Appeals (the "Board") for a driveway special permit and dimensional variances for the purpose of razing a lawfully nonconforming garage located at 30 Hillside Avenue in Chelsea (the "Locus"), and replacing it with a larger, single-family home. The existing garage is nonconforming as to front, side, and rear setbacks, and the lot on which it sits is smaller than the minimum size mandated by the Chelsea Zoning Ordinance (the "Ordinance"). Its current use, the storage of snowplowing equipment, is also nonconforming. The proposed house will be larger than the garage, extending down the lot's steep rearward slope. Like the existing garage, it will encroach on all setbacks, only more so, and the lot size will likewise remain under the requisite minimum. By a vote on March 17, 2015, and in a written decision filed with the city clerk on April 6, 2015, the Board granted Duca a special permit with respect to driveway requirements and four dimensional variances. The plaintiffs live on a parcel abutting the rear of the Locus, at the foot of the hill that occupies the Locus. On April 21, 2015, they filed a complaint appealing the Board's decision pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17.

The case was tried before me on January 24, 2017, with testimony from three fact witnesses and one expert witness. Following the filing of post-trial submissions by plaintiffs and defendants respectively on March 3 and March 6, 2017, I took the matter under advisement. For the reasons stated below, I find and rule that the decision of the Board approving the private defendants' application was legally untenable, arbitrary and capricious, and must be annulled.

FACTS [Note 1]

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence admitted at trial, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, weight, and inferences reasonably to be drawn from the evidence admitted at trial, I make factual findings as follows:

The Parties and the Properties

1. The plaintiffs Francis Resca and Jane Moore own and reside in a single-family home at 67 Eleanor Street, Chelsea, Massachusetts.

2. The defendant Lawrence Meads is the record owner of the Locus at 30 Hillside Avenue, Chelsea, Massachusetts. The western lot line of the Locus abuts the eastern lot line of the plaintiffs' property.

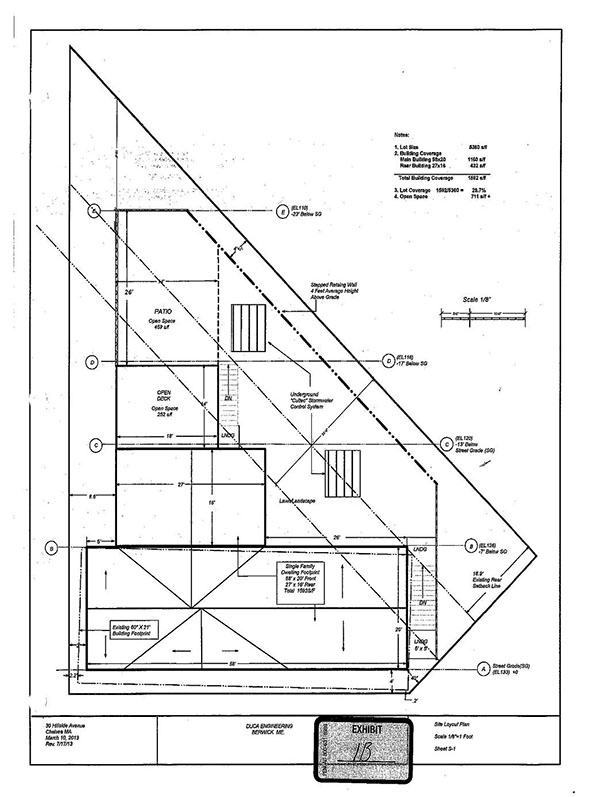

3. The Locus is a 5,360-square-foot lot. The lot is in the shape of a quadrilateral, with four unequal sides, somewhat resembling a triangle. [Note 2] The northeast lot line of the Locus, abutting Hillside Avenue, is the site of the existing garage on the Locus. From its front at Hillside Avenue, the Locus slopes steeply down towards the west, descending approximately twenty-four feet in elevation to the rear, where it abuts the plaintiffs' property. [Note 3]

4. The plaintiffs' property, 67 Eleanor Street, abuts 70 feet of the rear boundary of the Locus. The plaintiffs' property sits at the foot of the hill that makes up the Locus, with the one-story garage on the Locus at the top of the hill abutting Hillside Avenue, on the part of the Locus farthest away from the plaintiffs' property. The rear of the garage is approximately thirty-six feet away from the plaintiffs' rear lot line at its closest point. The hillside that separates the plaintiffs' property from the existing garage on the Locus is presently wooded and undeveloped.

The Existing Garage

5. The existing structure on the Locus is a one-story, sixty-foot by twenty-one-foot rectangular concrete block garage that is currently used for storage of plowing equipment. [Note 4]

6. The front, sixty-foot edge of the garage next to Hillside Avenue is approximately 0.2 feet back from the Hillside Avenue lot line on its western corner, and is approximately three feet back from the lot line at its eastern corner. The Ordinance requires a front-yard setback of twenty feet. [Note 5] The side yards of the garage are similarly significantly nonconforming, with one side set back 2.2 feet from the lot line and the other side set back forty inches. The Ordinance requires a side-yard setback that is one quarter of the building's height, but with each side yard not being less than five feet, and the aggregate of both side yards together not being less than twenty feet. [Note 6] The southwestern corner of the garage is approximately seventeen feet from the rear lot line. The Ordinance requires a rear-yard setback of twenty-five feet.

The Proposed Structure

7. Before the Board were applications for a driveway special permit and a number of dimensional variances so as to remove the garage and replace it with a four-bedroom single-family dwelling.

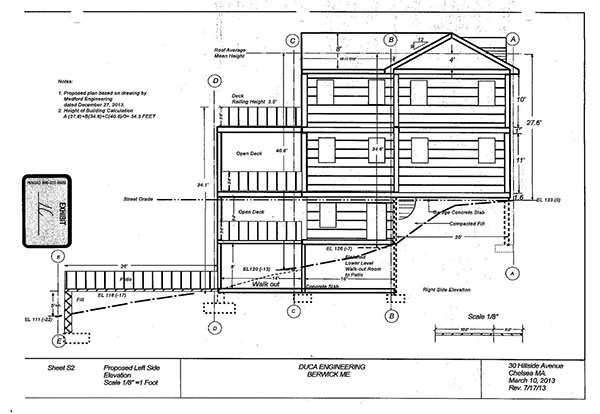

8. The proposed dwelling is designed with a front section that is roughly coincidental with the footprint of the existing garage, but is two stories in height instead of one story. A rear, three-story section would extend down the slope toward the rear of the Locus for sixteen feet, entirely outside the footprint of the existing garage. This section is proposed to be 31.6 feet in height relative to Hillside Avenue, like the front section, but because it is built on a steep slope, its height above grade at its highest (rear) point is 44.6 feet. Three stories of stacked decks would be attached to this section, extending 14 feet further toward the rear of the Locus. Finally, a 26-foot long "patio" (really another deck), built on footings and with its rear railing about 8 feet above existing grade, would extend from the rear of the stacked deck structure to within approximately four feet of the rear lot line that abuts the plaintiffs' property.

9. A stepped retaining wall, between four to six feet high depending on the relative grade at different points along its length, is proposed to run from the corner of the patio for fifty feet parallel to and set back approximately four feet from the rear lot line.

The Plaintiffs' Appeal

10. Jay Duca, on behalf of record owner Lawrence Mead, applied for a special permit to alter the parking requirements of the Ordinance, and for variances from the front-yard setback, rear-yard setback, side-yard setback, and minimum lot requirements of the Ordinance. [Note 7]

11. The Board held public hearings on the application on January 13, 2015 and March 17, 2015. [Note 8]

12. On March 17, 2015, the Board voted to issue the requested special permit and the four requested dimensional variances, and filed a written decision with the City Clerk consistent with this vote on April 6, 2015.

13. On April 21, 2015, the plaintiffs filed a timely complaint appealing the Board's decision pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17.

DISCUSSION

Standing

As with most zoning appeals, the threshold issue is whether the plaintiffs have standing to bring this appeal under G.L. c. 40A, § 17. "Under the Zoning Act, G.L. c. 40A, only a 'person aggrieved' has standing to challenge a decision of a zoning board of appeals." 81 Spooner Rd., LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012). G.L. c. 40A supplies a presumption that "abutters, owners of land directly opposite on any public or private street or way, and abutters to the abutters within three hundred feet of the property line of the petitioner" are aggrieved, and therefore have presumptive standing. G.L. c. 40A, § 11. "The defendant, however, can rebut the presumption by showing that, as a matter of law, the claims of aggrievement raised by an abutter, either in the complaint or during discovery, are not interests that the Zoning Act is intended to protect

Alternatively, the defendant can rebut the presumption by coming forward with credible affirmative evidence that refutes the presumption, that is, evidence that warrant[s] a finding contrary to the presumed fact of aggrievement, or by showing that the plaintiff has no reasonable expectation of proving a cognizable harm." Picard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Westminster, 474 Mass. 570 , 573 (2016), quoting Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 33 (2006). Rather than providing its own evidence, the defendant may also rely on the plaintiff's lack of evidence, established through discovery, to rebut a claimed basis for standing. See Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, supra, 447 Mass. at 35. If a defendant fails to offer sufficient evidence to rebut the plaintiff's presumption of standing, the abutter "is deemed to have standing, and the case proceeds on the merits." 81 Spooner Road, LLC, supra, 461 Mass. at 701.

If a defendant has successfully rebutted the presumption, the burden then shifts to the plaintiff, with no benefit from the presumption, "to prove standing by putting forth credible evidence to substantiate the allegations." Id., at 700. To do so, "[t]he plaintiff must 'establish by direct facts and not by speculative personal opinionthat his injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community.'" Id., quoting Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, supra, 447 Mass. at 33. Furthermore, "[a]ggrievement requires a showing of more than a minimal or slightly appreciable harm

The adverse effect on a plaintiff must be substantial enough to constitute actual aggrievement such that there can be no question that the plaintiff should be afforded the opportunity to seek a remedy

Put slightly differently, the analysis is whether the plaintiffs have put forth credible evidence to show that they will be injured or harmed by proposed changes to an abutting property, not whether they simply will be 'impacted' by such changes." Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 122 (2011). Nonetheless, "a plaintiff is not required to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that his or her claims of particularized or special injury are true. 'Rather, the plaintiff must put forth credible evidence to substantiate his allegations.'" Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 441 (2005), quoting Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 722 (1996). This "credible evidence" standard has both qualitative and quantitative components: "[q]uantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made. Qualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the board's action." See id. (internal citation omitted). The facts offered by the plaintiff must be more than merely speculative. Sweenie v. A.L. Prime Energy Consultants, 451 Mass. 539 , 543 (2008).

Presumption of Standing. There is no dispute that the plaintiffs are abutters to the Locus, and thus enjoy a presumption that they are aggrieved within the meaning of G.L. c. 40A, § 17. The defendants consequently bear the initial burden of supplying credible evidence that the plaintiffs will experience no injury sufficient to confer standing. In their complaint, the plaintiffs indicate that they are aggrieved by the threat of excessive water runoff, the potential for landslides, a diminution in property value, and "other consequences" not specifically enumerated. The defendants did not propound any discovery to identify all particular grounds for aggrievement and thereby limit the grounds provable at trial; accordingly, the plaintiffs permissibly offered testimony at trial of aggrievement on the basis of density concerns. Each of the plaintiffs' articulated bases for standing (water runoff and "landslides" (erosion); diminution of property value; and density-related overcrowding) is considered below.

Defendants' Rebuttal of the Presumption. To rebut the presumption afforded to the plaintiffs, at trial the defendants offered the testimony of James Burke, a qualified civil engineer. Burke testified that he used hydrologic modeling to determine the state of existing water runoff, and then modeled the extent of water runoff that would be produced by the proposed structure. He indicated that, in order to mitigate storm water, the proposed construction would include the installation of a three-by-three grouping of high-density polyethylene plastic devices for the purpose of capturing runoff and allowing it to percolate into the ground (known as a Cultec storm water recharge system). He stated that this system was significantly over-designed for the purpose of the proposed project, as it was designed to effectively control runoff from a twenty-five year event, and likely possesses the capability to do so for storms as large as a hundred-year event. Additionally, he testified that flattening the slope and adding the retaining wall will likewise reduce erosion and runoff towards the abutters. He testified that, with this storm water control system and the changes in gradation of the slope, the proposed structure will in fact produce less runoff and flooding than currently results from the Locus. Burke also addressed the impact of the proposed structure on the threat of erosion. He indicated that landslides are created by saturated soils near the surface losing cohesive friction; he stated that, because the proposed construction would flatten the slope and place storm water below the surface, thereby reducing surface saturation, there would be no danger of a landslide occurring as a result of the project. Burke's testimony serves as credible evidence that the plaintiffs will not be aggrieved by increased water runoff or the danger of landslides or other erosion; accordingly, I find that the defendants successfully rebutted the presumption of standing arising from these two areas of concern. Once this presumption receded, the burden shifted to the plaintiffs to establish aggrievement by credible evidence. As to the particular harms of storm water runoff and landslides, the plaintiffs failed to adduce any such credible evidence.

While neither increased runoff and nor the threat of landslides and erosion may therefore serve to provide the plaintiffs with standing, the plaintiffs were not limited to these two forms of aggrievement. The plaintiffs alleged in their complaint that they would likewise be aggrieved by a diminution in value of their property. The value of real property is not an interest protected by the Zoning Act unless a local bylaw incorporates it as an interest or unless diminution in property value is a function of damage to another protected interest. See Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 123 (2011). "[A]n interest that is not otherwise sufficient to serve as an independent basis for standing may become so when defined in the bylaw as a protected interest." Bergmann v. Town of Lexington Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 25 LCR 154 , 160 (Mass. Land Ct. Mar. 13, 2017) (Speicher, J.), citing Martin v. Corp. of Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, 434 Mass. 141 , 147 (2001). The Ordinance here has provided such protection for conservation of value: Section 34-1 states that that one of the Ordinance's objectives is "to conserve the value of land and buildings." This incorporates property value as an additional interest protected under the bylaw, and harm to this interest may therefore serve as a source of aggrievement for the purposes of standing. See Epstein v. Bd. of Appeal, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 752 , 761 n.17 (2010). Having articulated a diminution of value in the complaint, the plaintiffs were afforded the presumption that they were indeed aggrieved on this basis, and the defendants held the burden of producing credible evidence indicating that this was not so. The defendants offered no evidence as to the impact, or lack thereof, of the proposed home on the value of the plaintiffs' property. [Note 9] Evidence concerning the unlikelihood of landslides and proper handling of runoff is not by itself sufficient to rebut a claim of diminution of value, absent some other explanatory evidence that affirmatively connects these to value and credibly indicates no overall harm to value, at least where there is (as there is here) other evidence to support the plaintiffs' claim of diminution of value. "When a defendant fails to offer evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact, the presumption of aggrievement is not rebutted, the abutter is deemed to have standing, and the case proceeds on the merits." 81 Spooner Rd., LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 701 (2012). Without such evidence, the presumption of aggrievement remains intact.

The plaintiffs alleged and established at trial an additional source of aggrievement in the form of the density-based harm of overcrowding, testifying that they use a raised platform or deck at the rear of their property, that the proposed new structure, extending to near the same rear lot line, and at a higher elevation, will loom over them and add to a sense of crowding. The defendants have not produced credible evidence sufficient to rebut the presumption, and indeed the testimonial evidence presented at trial, that the plaintiffs are aggrieved in this respect. A claim of crowding is fundamentally grounded in density concerns, and impact on density is indeed an interest protected under the provisions of the Bylaw. Section 34-1(b)(5) provides that one of the enumerated purposes of the Bylaw is "to prevent overcrowding of land." Additionally, the dimensional requirements of the Bylaw plainly function as a mechanism for controlling the density of construction in the city. See Marhefka v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 515 , 520 (2011). Where the local zoning scheme affords such protection with respect to density, the courts of the Commonwealth have recognized that "[c]rowding of an abutter's residential property by violation of the density provisions of the zoning by-law will generally constitute harm sufficiently perceptible and personal to qualify the abutter as aggrieved and thereby confer standing to maintain a zoning appeal." Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 297 (2008). See 81 Spooner Rd., LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, supra, 461 Mass. at 705. The erection of a structure at close quarters to a plaintiffs' property may in and of itself create an injury sufficient to provide a basis for aggrievement. See Bertrand v. Bd. of Appeals of Bourne, 58 Mass. App. Ct. 912 , 912 (2003). See also Chambers v. Building Inspector of Peabody, 40 Mass. App. Ct. 762 , 768 (1996) (holding that "a building located closer than planned to the plaintiffs' property line that is eleven percent larger than the one first proposed" is evidence of aggrievement). Furthermore, the fact that construction lies in an overcrowded district serves to further generate cognizable aggrievement, as "an abutter has a well-recognized legal interest in 'preventing further construction in a district in which the existing development is already more dense than the applicable zoning regulations allow.'" Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 8 , 11 (2009), quoting Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 297. See Mauri v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 336 , 340 (2013) ("The proposed additional dwelling will lie within twelve feet of their home and contain a number of windows aligned to allow a view into their home. Regardless of whether the minimum setbacks are met, we cannot fairly say the [plaintiffs'] allegations of aggrievement caused by further development of an already overly dense zoning district in violation of the density provisions of the zoning ordinance fail to confer standing on them on these facts.").

Here, both the existing structure and size of the lot already violate the dimensional requirements of the Ordinance; even without looking beyond the Locus itself, this alone serves to indicate to some degree that the area is already "more dense than the applicable zoning regulations allow." Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal, supra, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 11.

Compounding this is the apparent existence of other lots in the immediate vicinity of the Locus that are also plainly dimensionally nonconforming. For example, not only is the lot area of the Locus itself under the requisite minimum mandated by the Ordinance, the four lots directly to the west of the Locus are each substantially smaller than the Locus and likewise violate the same density requirements. [Note 10] Moreover, the court's view of the surrounding area revealed a considerable number of nearby homes that appeared to be nonconforming as to setback requirements. [Note 11]

Quite aside from the current state of neighborhood density, the proposed construction will undoubtedly have a meaningful density-related impact that is particularized to the plaintiffs' own property. Though the proposed structure appears modest when viewed from the street, its vertical growth as it progresses downslope presents a starkly different appearance to its rear abutters, especially the plaintiffs. As seen from the rear of the plaintiffs' property, the stacked decks and rear section of this home will respectively rise to heights of forty-three and fifty feet, and this towering structure will be situated less than twenty-five feet from the property line shared with the plaintiffs. The raised "patio", which is in truth another deck with a rail height about eight feet above existing grade, will likewise come within four feet of their property line. [Note 12] This proposed project is comparable in effect to the type of closely-built construction repeatedly recognized by the courts as sufficiently impacting a neighbors' property to create a cognizable harm for the purposes of standing. See Mauri v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 336 , 340 (2013) (structure twelve feet from plaintiffs' home, with windows aligned towards plaintiffs); Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal, supra, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 12 (three-story structure fourteen feet from the plaintiff's house); Epstein v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, supra, 77 Mass. App. Ct. at 754 (abutter had standing to appeal grant of variance for building to be as close as one foot from existing building); McGee v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 930 , 931 (2004 (abutters had standing where proposed new construction would come within a foot of their window); Gottfried v. Betron, 25 LCR 1 (Mass. Land Ct. Jan. 3, 2017) (Piper, J.). Like the construction in those cases, the defendants' proposed structure here is quite close to the plaintiffs' property, and from the plaintiffs' perspective, of considerable height; it likewise will add to the current violations of dimensional requirements intended by the Ordinance to regulate neighborhood density. This is precisely the manner of "[c]rowding of an abutter's residential property by violation of the density provisions of the zoning by-law" that constitutes an injury sufficient to confer standing. Dwyer v. Gallo, supra, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 297. Cf. Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal, supra, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 12; McGee v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, supra, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 931.

Accordingly, as the plaintiffs have presented two independently sufficient grounds for standing, and the defendants have failed to rebut on these issues, I find that the plaintiffs have standing to appeal the decision of the Board, and the case must proceed to the merits of that decision.

The Merits

Standard of Review. The court's inquiry in reviewing the decision of a board of appeals or a special permit granting authority is a hybrid requiring the court to find the facts de novo, and, based on the facts found by the court, to affirm the decision of the board "unless it is based on a legally untenable ground, or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary." MacGibbon v. Bd. of Appeals, 356 Mass. 635 , 639 (1970). This involves two distinct inquiries, the first of which looks to whether a zoning board's decision applied incorrect standards or criteria. See Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003). In this first inquiry, the court determines whether the decision is premised "on a standard, criterion or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws. Here, the approach is deferential only to the extent that the court gives 'some measure of deference' to the local board's interpretation of its own zoning by-law. In the main, though, the court determines the content and meaning of statutes and by-laws and then decides whether the board has chosen from those sources the proper criteria and standards to use in deciding to grant or to deny the variance or special permit application." Id. at 73 (internal citations omitted). Only after determining that the decision was not based on a legally untenable ground does the court then proceed to the second, more deferential inquiry, examining whether "any rational view of the facts the court has found supports the board's conclusion

" Id. at 75. The court may not overturn the board's decision unless "no rational view of the facts the court has found supports the [zoning board's] conclusion..." Id. at 74-75.

Applying this two-part framework to the relief granted by the Board's decision, I find that the plaintiffs' proposed home required both a special permit for a change in a nonconforming use or structure, and variances, yet the Board failed to make the findings necessary to grant the former, and lacked any rational basis for granting the latter.

Special Permit. First, the Board properly granted a special permit for a waiver of the dimensional requirements pertaining to parking, but failed to make any findings or to explicitly grant a required special permit for a change in nonconforming use as required by G.L. c. 40A, § 6.

Jay Duca requested [Note 13] and was granted a special permit for relief from the off-street parking requirements of Section 34-106(c)(1) of the Ordinance, which requires that an intervening twenty-foot driveway accompany parking facilities within the ground floor of a structure. The Board may waive this requirement through the issuance of a special permit under Section 34-106(j), which states: "Any parking requirement set forth in this section may be reduced upon the issuance of a special permit by the zoning board of appeals, if the board finds that the reduction is not inconsistent with public health and safety, or that the reduction promotes a public benefit." In addition to the finding required by Section 34-106(j), the Ordinance also includes in Section 34-214 the criteria to be generally applied whenever the Board issues a special permit. This section states as follows:

Special permits shall be granted by the special permit granting authority, unless otherwise specified herein, only upon its written determination that the benefit to the city and the neighborhood outweigh the adverse effects of the proposed use, taking into account the characteristics of the site and of the proposal in relation to that site. In addition to any specific factors that may be set forth in this chapter, the determination shall include consideration of each of the following: (1) Social economic or community needs which are served by the proposal; (2) traffic flow and safety, including parking and loading; (3) adequacy of utilities and other public services; (4) neighborhood character and social structures; (5) impacts on natural environment, including drainage; (6) potential fiscal impact, including impacts on city services, tax base and employment.

The Board's decision expressly applied the standard provided in Section 34-214 of the Ordinance, and its implementation of these generally applicable criteria was proper. Section 34-214 states that these criteria are to be applied unless otherwise specified, and there is no indication in the Ordinance that a special permit for a parking waiver under Section 34-106(j) does not also fall under the general umbrella of Section 34-214. However, with regard to the additional finding mandated by Section 34-106(j) itself, the Board made no explicit mention of the particular standard of whether "the reduction is not inconsistent with public health and safety, or that the reduction promotes a public benefit." [Note 14] Nevertheless, despite this lack of direct reference, it is clear that in its consideration of Section 34-214's criteria, the Board implicitly applied the standard required by Section 34-106(j) as well. The Board considered Section 34-214's criterion of "Traffic Flow and Safety, including parking and loading", and in doing so, stated that it did "not foresee the location and the size of the site as having a significant negative impact on traffic flow and safety." This indicates that the Board employed an evaluation that was functionally identical to that mandated by Section 34-106(j).

Though the Board properly applied Section 34-214, this does not conclude the court's analysis, as the court must look to the content and meaning of all relevant ordinances to determine whether the Board has chosen from the proper sources in deciding to grant the application; it is thus necessary to consider whether the Board failed to make additional findings also necessary to the manner of relief granted. See Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, supra, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73. Here, the court must look to the standards required not only for a parking waiver, but also those applicable to an alteration of a nonconforming structure. G.L. c. 40A, § 6 governs pre-existing, nonconforming structures and uses, and sets the minimum tolerance that municipalities must provide to such structures and uses. See G.L. c. 40A, § 6; Almeida v. Arruda, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 241 , 243 n.5 (2016). The second sentence of G.L. c. 40A, § 6 requires the board to make findings when allowing an alteration or change in a nonconforming use or structure. [Note 15] See G.L. c. 40A, § 6; McLaughlin v. Brockton, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 930 , 932 (1992) ("An ordinance that permitted an alteration of a nonconforming use in the absence of such a finding would be in violation of the literal mandate of § 6."). Section 6 provides, in relevant part:

Pre-existing nonconforming structures or uses may be extended or altered, provided, that no such extension or alteration shall be permitted unless there is a finding by the permit granting authority or by the special permit granting authority designated by ordinance or by-law that such change, extension or alteration shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming use [or structure] to the neighborhood.

G.L. c. 40A, § 6 (emphasis added). The Ordinance, in a parallel implementation of the standard provided in G.L. c. 40A, § 6, allows an applicant to alter a nonconforming structure through receipt of a special permit. Section 34-51(c) of the Ordinance provides as follows:

The zoning board of appeals may grant a special permit to reconstruct, extend, alter, or change a nonconforming structure in accordance with this section only if it determines that such reconstruction, alteration or change shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming structure to the neighborhood. The following types of changes to nonconforming structures may be considered by the zoning board of appeals: (1) reconstructed or extended; (2) change from one nonconforming structure to another, less detrimental nonconforming use.

This section essentially mirrors the requirements of the second sentence of Section 6, with the added clarification that it shall also apply to a reconstruction of a nonconforming structure. [Note 16] Under G.L. c. 40A and its direct cognate in the Ordinance, the Board therefore may allow a reconstruction, alteration, or change, but only upon making a so-called "Section 6" finding that the proposed change will not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood.

The court affords the Board "some measure of deference" in its interpretation of the ordinance and its resulting choice of the applicable criteria and standards. Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, supra, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73. Yet even taking this deferential view of the Board's decision, it is beyond doubt that the defendants' proposal is, at the very least, a "reconstruction" of a nonconforming structure as that term is commonly used. Moreover, in the decision itself the Board indicates that the proposed structure will, in fact, extend the property's existing nonconformities. The standard of Section 34-51(c) and the second sentence of G.L. c.

40A, § 6 therefore plainly applies to the defendants' application; indeed, the defendants themselves have indicated that the standard of this section is properly applicable to their project. [Note 17] The Board was thus empowered to approve the application only after evaluating the project pursuant to G.L. c 40A, § 6 and the corresponding section of the Ordinance, and making a Section 6 finding. The Board did not employ this standard, and failed to make the requisite finding that the proposed structure would not be substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the existing nonconforming structure. It does not appear that the defendants requested relief under this section, and the decision makes no reference to this section of the Ordinance. [Note 18] Unlike the Board's failure, discussed above, to explicitly apply the special permit standard of Section 36-106(j) for parking waivers, there is no other parallel language in the decision sufficiently indicative of an implicit application of Section 34-51(c).

Variances. The failure to make the required Section 6 finding is alone sufficient to invalidate the Board's decision, but if that was the only source of invalidity, a remand could remedy the deficiencies in the Board's decision. However, the Board's accompanying grant of four variances presents issues for review as well, as they are equally essential to the proposed construction, and their deficiencies are thus independently fatal to the decision. These variances provide relief from the front-yard setback, rear-yard setback, side-yard setback, and minimum lot size requirements of the Ordinance. The defendants contend, as a threshold matter, that the court need not even evaluate the merits of these variances, as, they argue, the proposed changes to this nonconforming structure did not require any variances at all. In evaluating whether variances were required, the court must first determine the content and meaning of the relevant bylaws, and look to whether the Board chose from the proper criteria and standards. Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, supra, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73.

G.L. c. 40A, § 6 generally establishes relief necessary for alteration or reconstruction of a nonconforming use or structure. Section 6 provides as follows:

[A] zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to structures or uses lawfully in existence or lawfully begun before the first publication or notice of the public hearing on such ordinance or by-law required by section five, but shall apply to any change or substantial extension of such use after the first notice of said public hearing, and to any reconstruction, extension or structural change of such structure and to any alteration of a structure. . . . Pre-existing nonconforming structures or uses may be extended or altered, provided, that no such extension or alteration shall be permitted unless there is a finding by the permit granting authority . . . that such change, extension or alteration shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming [structure or] [Note 19] use to the neighborhood."

(emphasis added). Accordingly, Section 6 "permits extensions and changes to nonconforming structures if (1) the extensions or changes themselves comply with the ordinance or by-law, and (2) the structures as extended or changed are found to be not substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood than the preexisting nonconforming structure or structures." Rockwood v. Snow Inn Corp., 409 Mass. 361 , 364 (1991). The second step in this evaluation reflects the mandatory "Section 6 finding", discussed above, that may be issued by special permit (but is absent here). Pursuant to the first step, though, which requires that the changes comply with the bylaw, any extension of an existing nonconformity or creation of a new nonconformity would also require an applicant to obtain a variance. See Palitz v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Tisbury, 470 Mass. 795 , 802 (2015) (holding that both creation of new nonconformities and expansion of existing nonconformities required variances). [Note 20]

This requirement is incorporated into the provisions of the Ordinance. Just as the Ordinance's special permit standard under Section 34-51(c) mirrors the second step of Section 6 concerning detriment to the neighborhood, the Ordinance also provides a standard that effectively incorporates the first step of Section 6, as described in Rockwood, which requires changes to comply with the bylaw or otherwise require a variance. Section 34-51(e) of the Ordinance provides as follows:

The reconstruction, extension or structural change of a nonconforming structure in such a manner as to increase an existing nonconformity, or create a new nonconformity, including the extension of an exterior wall at or along the same nonconforming distance within a required yard, shall require the issuance of a variance from the zoning board of appeals.

This section of the Ordinance mandates that an applicant obtain a variance under the same circumstances (the increase of an existing nonconformity or creation of a new nonconformity) as would be required by Section 6. See Palitz v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Tisbury, supra, 470 Mass. at 802.

Here, it is undisputed that the proposed project is a reconstruction, extension, or change of a nonconforming structure; the Board was therefore obligated to evaluate the application pursuant to the parallel standards of Section 34-51(e) and G.L. c. 40A, § 6, determine whether the proposal would increase or create and nonconformities, and if so, then evaluate the request for the issuance of variances. The Board's Decision stated that the proposed structure would "extend existing non-conformities, but will not create new nonconformities." [Note 21] The Board thus made the correct inquiry, employing the standard provided in Section 34-51(e) to evaluate the potential need for variances, and the Board correctly concluded that existing nonconformities would be extended, thus requiring the issuance of variances.

First, as to the variance from the minimum lot size required for a single-family dwelling in an R-1 district, it is undisputed that the size of the lot currently is and will continue to be nonconforming. The Locus is 5,360 square feet, while the Ordinance requires that a lot in an R1 District be a minimum of 7,500 square feet. The size of the lot will not shrink under the defendants' proposal, while the construction proposed by plaintiff will increase the footprint of the structure present on the undersized lot. The Supreme Judicial Court, in Bransford v. Zoning Board of Appeals and Bjorklund v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals has recognized that the physical expansion of a building on a nonconforming lot may constitute an increase in lot size nonconformity, whether or not the lot size itself changes. See Bjorklund v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 450 Mass. 357 , 362 (2008); Bransford v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 444 Mass. 852 , 861 (2005). In Bransford, the court was first presented with the question of whether an expansion of a structure that was in all other ways conforming, but which would be upon a lot nonconforming as to size, constituted an "increase" in the lot size nonconformity. The lower court held that it was, and this was upheld by an equally divided Supreme Judicial Court, which concluded that such an alteration could constitute an increase. The opinion upholding the lower court decision noted that, while the lot size would remain unchanged, "[t]he expansion of the residence's footprint, and the expansion in living area, will, at the very least, tend to reduce the open space previously existing on the lot and to increase the density of the residential neighborhood." Bransford v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, supra, 444 Mass. at 861. Subsequently, in Bjorklund v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, the Court was again presented with a proposed structure that was larger than the existing structure, but was only nonconforming as to lot size; thus, once more, "the sole issue before [the court was] whether the plaintiffs' proposed reconstruction increases the nonconforming nature of the structure." Bjorklund v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, supra, 450 Mass. at 362 (emphasis in original). The majority opinion of the Court went on to expressly adopt the reasoning previously set forth in Bransford, holding that the larger structure did in fact constitute an increase in the lot size nonconformity. See id. See also Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal, 81 Mass. App. Ct. at 401 ("Because the lot was undersized, any house there violated the minimum lot size requirement. In such a circumstance, an increase in the size of an existing building could 'intensify' the nonconformity

").

The circumstances presented by these cases are directly analogous to the facts of the present case. [Note 22] The proposed new dwelling is larger than the existing garage structure, and will be on a lot that remains nonconforming as to area. It is true that where the size of a lot is nonconforming, some small scale additions, such as the construction of dormers, enclosure of a porch, or construction of a gardening shed, may be so de minimis an expansion that they "could not reasonably be found to increase the nonconforming nature of a structure." Bjorklund v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, supra, 450 Mass. at 363. However, the expansion of the structure here cannot rationally be said to have a comparably minimal effect. The defendants intend to construct a structure with a footprint that is more than a third larger (by 432 square feet) than the footprint of the original structure, with more than triple the gross floor area of the existing structure (not counting the decks), expanded further by sizable roofed decks and a patio, all at a considerably greater height above grade than currently exists. Given the holdings in Bjorklund and Bransford, a consistent determination here that the significant expansion of the proposed home's footprint constitutes an increase to the lot size nonconformity, and therefore requires variances, was rational and within the Board's authority.

The remaining variances were issued for the front, rear, and side-yard setbacks. The existing structure encroaches upon each of these setbacks, and the proposed structure will likewise continue to encroach to varying degrees in each, but with a building that is substantially greater in height, and encroaches to a greater degree and in locations where no such encroachment on the required setback previously existed. Regardless of whether each encroachment itself is increased, decreased, or remains the same, this vertical growth alone within the required setback is an extension of an encroaching wall that increases the structure's nonconformity with the setback requirements. In Goldhirsh v. McNear, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 455 , 461 (1992), the Appeals Court rejected the notion that adding floors to a structure would not increase a setback nonconformity as long as it stayed within the existing bounds of the encroachment. It noted that "[w]hether the addition of a second level to the carriage house will intensify the [setback] nonconformity is a matter which must be determined by the board in the first instance. The fact that there will be no enlargement of the foundational footprint is but one factor to be considered in making the necessary determination or findings." Goldhirsh v. McNear, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 455 , 461 (1992). A board may thus rationally find that such a vertical extension "will increase the nonconformity because it will add greater mass

into the setback area", regardless of the fact that there may be no additional horizontal encroachment into the setback. Caliri v. Baker, 14 LCR 556 , 558 (Mass. Land Ct. 2006) (Sands, J.).

This conclusion is further supported by the Ordinance's express recognition that increased encroachment towards the lot line is not strictly necessary for the Board to find an increase in a setback nonconformity. Section 34-51(e) specifically includes "the extension of an exterior wall at or along the same nonconforming distance within a required yard" as an example of an increased nonconformity. It is not uncommon for municipal ordinances to acknowledge such differing types of extension as an increasing nonconformity; indeed, many expressly delineate an alteration to height within a setback as a per se increase in a nonconformity, regardless of the degree of change to the lateral encroachment. See Eburn v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Dennis, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 1116 (2013) (Rule 1:28 Decision); Harrison v. Fouhy, 20 LCR 332 , 334 (Mass. Land Ct. June 26, 2012) (Grossman, J.), aff'd sub nom. Harrison v. St. Pierre, 84 Mass. App. Ct. 1128 (2014) (Rule 1:28 Decision); Liska v. Wells, 13 LCR 364 , 365 n.1 (Mass. Land Ct. June 30, 2005) (Piper, J.); McCarthy v. Wells, 14 LCR 65 , 66 (Mass. Land Ct. 2006) (Scheier, J.). The Ordinance here is broad in substance and does not so overtly label height extensions of encroaching walls as increases; yet it similarly signals an intention to treat extensions other than further lateral encroachment as increases, and its breadth allows the rational conclusion that increasing the height of a wall is in fact such an "extension of an exterior wall at or along the same nonconforming distance within a required yard." The Board therefore was reasonable in determining that the continued and increased violation of the front, side, and rear-yard setback requirements required the issuance of a variance for each of those yard encroachments.

The increased height of the structure within each of the setbacks serves alone as justification for requiring variances for each; even so, the proposed structure occasions other alterations specific to individual setbacks that likewise support the conclusion that the nonconformity as to each increased. Turning to the rear-yard setback, the southwest corner of the existing structure is currently located approximately seventeen feet from the rear lot line, while the Ordinance requires a rear-yard setback of twenty-five feet. As reconstructed, the southwest corner of the proposed structure's front section will encroach approximately the same distance into the rear-yard setback, and at the same location. However, there will also be a "patio" affixed to the structure that will come within four feet of the rear lot line. [Note 23] This patio falls within the Ordinance's definition of a "structure." [Note 24] Its encroachment on the rear lot line consequently fails to conform with the rear-yard requirements [Note 25] of the Ordinance to a substantially greater extent than the southwest corner of the existing structure. It is therefore reasonable to consider this an increase to the existing rear-yard setback nonconformity. Additionally, both the new rear section of the home and the decks [Note 26] affixed to its southern wall are entirely outside the existing footprint of the existing garage, and they each encroach into the required rear-yard setback at points where no intrusion previously existed. This is no different than extending an existing encroaching wall further along, rather than into, the setback; as noted above, the Ordinance does indeed expressly classify such an extension as an increase to a setback nonconformity.

As to the side-yard setback nonconformities, the Ordinance requires a side-yard setback of one quarter of the height of the structure, with a minimum yard of five feet, and an aggregate of both side yards not less than twenty feet. The existing structure is 2.2 feet from the eastern lot line, and ranges from about 2.5 inches to fifteen feet from the northwestern lot line. The first section of the proposed new dwelling, built approximately on the footprint of the existing structure, will be three feet from the eastern lot line, and still will be only forty inches from the northwestern lot line at its closest point (and will be greater in height). As to this front section, it indeed appears that the new construction will lessen the structure's nonconformity with the side- yard setback requirements of the Ordinance, but as with the rest of the building, will increase the mass of building within that setback. Additionally, the defendants' plan is not limited to simply constructing this front section alone. The additional rear section of the home, and its attached decks, will be 8.6 feet from the eastern lot line, which is exactly one quarter of the building's height. While this yard complies with the Ordinance's requirement for an individual yard, it nonetheless creates additional walls within the side setback, which violate the requirement that the aggregate setback of both side yards be greater than twenty feet. Thus a side-yard variance was required.

Having determined that the Board correctly required the applicant to apply for and receive variances, the next question is whether the Board's grant of these variances was within its discretion. Turning to the applicable criteria provided in the Ordinance, § 34-213(c) provides that the Board may only grant a variance upon a finding that:

the variance is sought because of soil conditions, shape, or topography of such land or structure and especially affecting such land or structure but not affecting generally the zoning district in which it is located; (2) A literal enforcement of the provisions of this chapter would involve a substantial hardship, financial or otherwise, to the petitioner or appellant. (3) Desirable relief may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good, and (4) Desirable relief may be granted without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of this chapter.

This implements the requirements that are statutorily mandated by G.L. c. 40A, § 10. [Note 27] As these elements are conjunctive, "[e]ach of the requirements of the statute must be met before a board may grant a variance." Furlong v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Salem, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 737 , 740 (2016). The Board distinctly applied each of these necessary elements in its decision, and therefore structured its analysis around the proper standards and criteria, satisfying the first step in the analytical framework. See Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, supra, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73.

The next consideration is whether any rational view of the facts supports the conclusions reached upon application of these criteria. See id. The Board concluded that the project proposed for the Locus satisfied each of the elements set out in G.L. c. 40A, § 10 and the Ordinance. The Board determined that the lot's (roughly) triangular shape and steep slope especially affected the land and structure but not the zoning district generally; that these conditions would create substantial hardship, "particularly financial", to the defendants if the Ordinance were to be literally enforced, as the lot would otherwise be rendered unbuildable; and that variances would neither create substantial detriment to the public good nor derogate from the purpose and intent of the Ordinance.

In order to sustain these conclusions, this court "must find independently that each of those conditions is met." Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, supra, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73 n.5. "The statutory criteria for a variance set out in G. L. c. 40A, § 10, are demanding, and variances are difficult to obtain," and are thus to be "sparingly granted." Mendes v. Board of Appeals, 28 Mass. App. Ct. 527 , 531 (1990). The first, often dispositive, element of "statutory hardship is usually present when a landowner cannot reasonably make use of his property for the purposes, or in the manner, allowed by the zoning ordinance

An applicant for a variance must show that the land's shape, alone or in combination with other features of the land, prohibits development consistent with the ordinance." Guiragossian v. Board of Appeals, 21 Mass. App. Ct. 111 , 118 (1985). "[A]n inability to maximize the theoretical potential of a parcel of land is not a hardship within the meaning of the zoning law." See Steamboat Realty, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 601 , 603 (2007), quoting McGee v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, supra, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 931.

The Board's initial conclusion that the soil, shape or topography of the land would impose substantial hardship if the Ordinance were to be enforced is not rationally supported by any view of the facts. The Board did not rely on any finding that there is any hardship related to soil conditions, and properly so, as there is no evidence of any hardship resulting from the soil conditions on the lot. James Burke, a soil evaluator registered with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, testified that he identified the soil on the property using National Conservation Service Maps as Hydrologic Group "B" soil, and stated that this soil was "fairly decent" for recharge of storm water. He gave no indication that the soil required the project to be sited at any particular location on the lot, and certainly did not indicate that the soil necessitated encroachment upon the setbacks. Indeed, when asked about the impact of the soil on the project, he testified that the soils were "not a concern." Other than Burke's testimony, there was no other evidence adduced concerning the soil conditions of the Locus. Accordingly, there exists no basis to conclude that there is a soil condition on the lot that would create a substantial hardship without relief from the Ordinance's dimensional requirements.

The Board did rely on a conclusion that the "triangle-like" shape of the lot, and its topography, in the form of its steep slope, provided sufficient justification for the granting of the variances. Addressing these issues, the "triangle-like" shape of the lot fails to reasonably justify the grant of either minimum lot size or setback variances, where, as here, it is the size of the lot that presents a problem for the proper siting of a building, not the shape. The shape of the lot "is not significantly unusual...this is not a case where the irregular perimeter of a parcel would prevent the siting of a building that conforms to existing zoning." Guiragossian v. Board of Appeals, supra, 21 Mass. App. Ct. at 116 (triangular shape of applicant's lot did not create hardship). Even constrained by the lot's present shape, the defendants may surely "make reasonable use of the lot for the purposes, or in the manner allowed by the zoning bylaw." Id. at 118. The fact that the lot's area falls below the requisite minimum is not a condition relating to "shape" that may justify the grant of a variance. The size of a lot is an attribute entirely different from its shape, and the former is not a proper consideration under the standard of G.L. c. 40A, § 10. See McCabe v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 10 Mass. App. Ct. 934 (1980); Shafer v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 966 , 967 (1987). Therefore, "the fact that the lot is too small to qualify as a buildable lot

gives the board of appeal no authority to grant a variance." Mitchell v. Bd. of App. of Revere, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 1119 , 1119 (1989). See McGee v. Bd. of Appeal of Bos., supra, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 931 ("An undersized lot is not a basis for a variance."); Tsagronis v. Board of Appeals, 415 Mass. 329 , 332 (1993) ("

ordinarily, failure to meet dimensional requirements does not satisfy the odd shape criterion of the statute

"); Di Cicco v. Berwick, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 312 , 314 (1989) ("Variances are not normally available to remedy deficiencies in frontage and area."); Guaranteed Bldrs., Inc. v. Heney, 21 LCR 203 , 205 (Mass. Land Ct. 2013) ( Foster, J.), aff'd sub. nom. Guaranteed Bldrs., Inc. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 85 Mass. App. Ct. 1101 (Feb. 21, 2014) (Rule 1:28 Decision). Were such a feature to be considered a hardship sufficient to grant a variance, "any undersized lot could claim unique conditions based upon its limited size, which would enable any undersized lot to obtain a varianceeffectively nullifying minimum dimensional zoning standards and unduly broadening the circumstances in which variances are appropriate." Krock v. Nelson, 23 LCR 486 , 489 (Mass. Land Ct. 2015) (Long, J.).

Furthermore, there is no corresponding substantial hardship arising from the topography of the Locus. The only unique topographical condition of the Locus is its downward slope of approximately twenty-four feet over a distance of approximately one hundred and nine feet. Although this is not an insubstantial decline, it bears no relation to the setback relief granted, and imposes no hardship that would be alleviated by deviation from a literal application of the Ordinance's dimensional regulations. While an effort to minimize construction on a steep slope might justify, at most, the front yard setback variance, so as to keep the building at the top of the slope, there is no corresponding justification for, in particular, the rear yard variance that allows construction far down the slope. The facts here are directly analogous to those of Mitchell v. Board of Appeals, in which the applicant received variances from setback and minimum lot size requirements on the basis that their undersized lot was located on a steep hill; the court rejected this justification, noting that "[t]he hardship in this case is not 'owing to the topography' of the land. The slope does not prevent the erection of a house. Rather, the hardship arises solely from the fact that the lot is too small to qualify as a buildable lot

" Mitchell v. Board of Appeals, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 1119 , 1120 (1989). See McGee v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, supra, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 931 (holding that variance not justified where "slope [was] irrelevant to the variances [applicant] sought").

Here, the slope is entirely unrelated to the fact that the defendants' lot is undersized, and the existence of that slope cannot justify the grant of a minimum lot size variance. The same must be said of the slope's relation to the setback variances, with the possible exception of the front-yard setback variance. There is no indication that the slope here necessitates construction that encroaches upon the side and rear setbacks. This is not a case where an applicant is forced to encroach on a required setback because a steep slope prevents construction in an area that complies: the defendants intend, even with the relief granted, to construct the majority of the structure on the steepest parts of the property. The slope has no impact on the defendants' ability to build a compliant home or one that would not increase the existing nonconformities of the Locus. The slope is not a topographical feature that would create hardship necessitating deviation from the Ordinance's dimensional regulations where it serves as an excuse for, rather than as a reason necessitating, encroachment into the required setbacks.

Finally, in evaluating potential hardship within the context of either shape or topography, it is necessary to consider the effect of the present nonconforming structure on the plaintiffs' ability to use the property without the need for any variances. While it would not be possible to construct a new building on the property without variances had there been no building existing on the property, the Board neglected the fact that there is an existing, lawfully nonconforming building presently on the property that is still available for use, and which, pursuant to a proper application of G.L. c. 40A, § 6, might be available to allow the alteration or replacement of the existing garage, on the same footprint, in a manner that would not require any variances if it did not increase any existing nonconformities. Such a redevelopment of the lot would not be constrained by shape or topography, and the Board made no findings, nor did the defendants present any facts that would support such findings if made, as to why the shape or topography of the land justify the additional incursions into the setbacks authorized by the Board (the rear-yard setback in particular) or expansion of the overall footprint of the building on the already undersized lot. The plaintiff here is perfectly able to continue using the structure in its existing non-conforming form, and there is no cognizable hardship imposed by remaining constrained to the use of this structure rather than one that is significantly larger. See Krock v. Nelson, supra, 23 LCR at 489.

CONCLUSION

The Board failed to make necessary findings required by G.L. c. 40A, § 6 and the corresponding provision of the Ordinance, and the Board's issuance of dimensional variances was legally untenable, and arbitrary and capricious. Had a finding pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 6 been the only relief required for the private defendants' proposed project, a remand to the Board would be appropriate. However, given the court's conclusion that the variances were not properly granted, and could not be properly granted under any circumstances for the project as presently proposed, a remand to the Board is not appropriate. Accordingly, the decision of the Board is hereby ANNULLED.

Judgment will enter accordingly.

Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 21 LCR 1 , 1 n.1 (Mass. Land Ct. 2013) (Sands, J.). Furthermore, it is notable that counsel for the City of Chelsea herself observed during closing arguments that, on one property neighboring the Locus, the house's deck appears to encroach into the rear yard setback, and that two other neighboring properties likewise seem very close to each other; presumably referencing the neighborhood's existing over-density to minimize the plaintiffs' complaints concerning the impact of the Locus, she stated that this state of affairs was simply "part of living in the city."

FRANCIS RESCA and JANICE MOORE v. JAY DUCA, LAWRENCE MEADS, CITY OF CHELSEA ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS; and JOHN DEPRIEST, JANICE TATARKA, ARTHUR ARESENAULT, JOSEPH MAHONEY, and MARILYN VEGA-TORRES, in their capacities as board members and not individually.

FRANCIS RESCA and JANICE MOORE v. JAY DUCA, LAWRENCE MEADS, CITY OF CHELSEA ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS; and JOHN DEPRIEST, JANICE TATARKA, ARTHUR ARESENAULT, JOSEPH MAHONEY, and MARILYN VEGA-TORRES, in their capacities as board members and not individually.