INTRODUCTION

In this case Bucks Hill Realty, LLC ("Plaintiff" or "Bucks Hill") asks the court to declare the rights it holds, if any, in a private way known as Saddleback Road in Wrentham, Norfolk County. Bucks Hill seeks a declaration that an easement for vehicular passage exists over that way, appurtenant to a parcel owned of record by Plaintiff, and burdening lands owned by the defendants. Plaintiff's land was retained by Plaintiff's predecessor in title when it sold house lots to the defendants or their predecessors. Plaintiff wants to court to establish Plaintiff's rights to use the disputed way to gain access to the retained parcel. Plaintiff contends that it holds those rights under recorded documents and plans, or, if not, by implication. I conclude that Bucks Hill has failed to carry its burden of proving that Plaintiff holds the easement rights it seeks.

Plaintiff brought this action against David J. Gill, Stephen A. Schairer, Grace D. Schairer, Donna MacLure, Kenneth MacLure, Donna Riccardi Gahan, and Richard E. Gahan both as individuals and as members of the Saddle Back Road Homeowners Association ("Defendants"). Defendants each have a title interest in a strip of land ("Saddleback Road" or "Easement B") over which Plaintiff's asserted easement for vehicular passage runs. Saddleback Road leads across four residential properties of the Defendants, beginning at Spring Street and then heading northward toward Plaintiff's parcel, which Plaintiff'says enjoys the benefit of the easement in dispute in this suit. As fee owners of these properties, Defendants are members of the Saddle Back Road Homeowners Association ("Association"), created by a Declaration of Covenant, Conditions and Restrictions ("Declaration") dated January 10, 1994, and recorded with the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds ("Registry") in Book 10334, Page 326.

Plaintiff'seeks a declaration, pursuant to G.L. 231A, §1, that it has an express (or, alternatively, an implied) appurtenant easement to use Saddleback Road, for passage by vehicle and foot to get between Plaintiff's parcel and the public street, and that Defendants have no legal basis to exclude Plaintiff from using Saddleback Road. Plaintiff asks that the court enjoin Defendants from interfering with Plaintiff's contemplated use of Saddleback Road. Plaintiff also seeks an award of costs and attorney's fees, and other appropriate relief. Defendants oppose Plaintiff's request for declaration that Plaintiff possesses any easement rights appurtenant to Plaintiff's parcel to use Saddleback Road.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Plaintiff filed this case on May 18, 2015. The court held a case management conference on August 13, 2015, at which counsel represented all parties. During the conference the court instructed Defendants to give notice of this litigation to mortgagees, if any, so they would have an opportunity to intervene, and established a schedule that called for discovery to close on January 31, 2016, with the first dispositive motion to be filed by February 28, 2016. On February 26, 2016, Plaintiff and Defendants filed cross-motions for summary judgment. On March 24, 2016 Defendants filed an opposition to Plaintiff's motion. On March 25, 2016 Plaintiff filed an opposition to Defendants' motion and related motions to strike. On May 13, 2016, the court held a hearing on the cross-motions for summary judgment. At the end of the hearing, the court, unconvinced that there were no material facts in dispute, ordered the parties to confer with their clients and report, by common agreement or separately, whether they would prefer: to have the court's ruling on the summary judgment motions and related motions, to have the case be decided a "case stated" basis, or to prepare for trial.

On June 14, 2016, counsel for the parties participated in a status conference by telephone. The parties at that conference reported agreement in principle to submit the case to the court on a case stated basis, by providing the court with a statement of agreed facts and exhibits, with the court to render a decision, finding facts and drawing inferences, based on the agreed record and the papers submitted in connection with the summary judgment motions. On August 8, 2016 the parties submitted a statement of agreed facts, a joint appendix of exhibits, and a stipulation of counsel that the parties agreed to the facts and exhibits for all purposes, and that the court was to decide the case on this agreed record and the previously submitted summary judgment materials. On August 23, 2016 the court requested that the parties supplement the agreed record with a complete certified copy of both the zoning bylaw and the subdivision rules and regulations in place when the Declaration and related plans were created. The parties, on August 30, 2016, submitted a response in which they declined to supplement the agreed record as the court had requested.

Given the signed stipulation by both parties that I may make findings, draw all reasonable inferences, and enter judgment based on the record materials previously submitted on summary judgment, together with the statement of agreed facts and the joint appendix of exhibits, and the stipulation also that these are all the materials needed to resolve the case, and taking into account the pleadings, and the arguments of counsel, Ifind the following facts and I rule as follows:

FINDINGS OF FACT

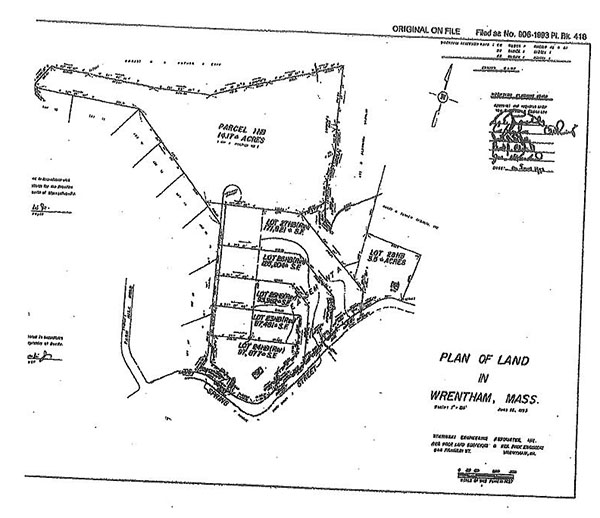

1. The original lots and lot dimensions of the subject properties are shown on a "Plan of Land in Wrentham, Mass., Scale 1"= 100', June 15, 1993" prepared by Stavinsky Engineering Associates, dated June 16, 1993, and recorded with the Registry as Plan 906-1993, in Plan Book 418 ("Plan 906") on December 21, 1993.

2. Bailey and Zahner Builders, Inc. was the developer and owner of the parent parcel from which the lots on Plan 906 were created. [Note 1]

3. The properties of the parties involved in this case are shown on Plan 906 starting from Spring Street to the south and looking northward in the following manner:

a. Lot 23HB - house lot of approximately 87,481 square feet.

b. Lot 25HB - house lot of approximately 93,982 square feet

c. Lot 26HB - house lot of approximately 125,204 square feet.

d. Lot 27HB - house lot of approximately 171,821 square feet.

e. Parcel l HB - undeveloped parcel of approximately 14.17 acres ("Parcel 1HB" or "Lot 1HB").

4. Lots 23HB, 25HB, 26HB, and 27HB all have over 125' of frontage along Spring Street.

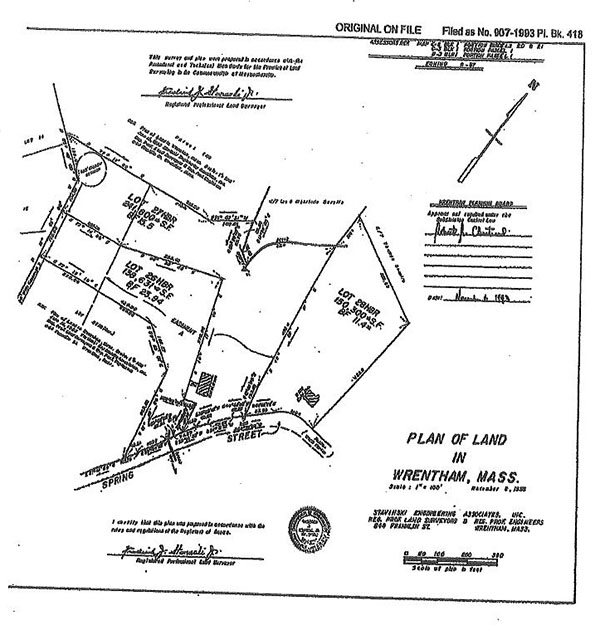

5. A second plan titled "Plan of Land in Wrentham, Mass., Scale 1"= 100', November 2, 1993 " and dated November 6, 1993 was recorded with the Registry as Plan 907-1993, in Plan Book 418 ("Plan 907") on Dec 21, 1993.

6. Two of the parcels relevant to this litigation are shown on Plan 907:

a. Lot 26 HBR - house lot of approximately 138,631 square feet.

b. Lot 27 HBR - house lot of approximately 241,800 square feet.

7. Lots 26HBR and 27HBR both have over 125' of :frontage along Spring Street.

8. Part of Lot 25HB and none of Lot 23HB are shown on Plan 907.

9. Lot 23HB is also known as 10 Saddleback Road and now is owned by defendants Richard E. Gahan and Carol Riccardi Gahan. [Note 2]

10. Lot 25HB is also known as 20 Saddleback Road and now is owned by defendant David J. Gill. [Note 3]

11. Lot 26HBR is also known as 30 Saddleback Road and now is owned by defendants Stephen A. Schairer and Grace D. Schairer. [Note 4]

12. Lot 27HBR is also lmown as 40 Saddleback Road and now is owned by defendants Kenneth MacLure and Donna MacLure. [Note 5]

13. Parcel l HB now is owned by Plaintiff, Bucks Hill Realty, LLC. [Note 6]

14. On January 11, 1994, Bailey & Zahner Builders, Inc. ("Declarant") recorded the Declaration. It is dated January 10, 1994 and recorded with the Registry in Book 10334, Page 326.

15. The Declaration contains and delineates certain rights, benefits, and obligations of the owners of the subject properties and establishes the Association.

16. I credit the sworn affidavits of certain Defendants that they understood at the time that they purchased their lots that the subdivision would be limited to four lots, that Parcel 1HB was fenced off at the end of Saddleback Road without a gate, and that for many years cows grazed on Parcel 1HB.

17. The Declaration under Article I, Definitions, states that:

"Common Area" shall mean the land marked "Easement B" shown on a plan entitled "Plan of Land in Wrentham, Mass.," dated June 15, 1993 drawn by Stavinski Engineering Associates, Inc., duly recorded with Norfolk County Registry of Deeds herewith. . . .

"Easement A" shall mean the land marked "Easement A" shown on the abovementioned plan drawn by Stavinski Engineering Associates Inc., and recorded as Plan No. 906 and 907 of 1993 Plan Book 418 of Norfolk Deeds. "Easement B" shall mean the land marked "Easement B" shown on the abovementioned plan drawn by Stavinski Engineering Associates, Inc., and recorded as Plan No. 906 and 907 of 1993 Plan Book 418 of Norfolk Deeds.

18. The Declaration under Article II, Property Rights states that:

Each owner of Lots 23HB, 25HB, 26HBR, 27HBR, and 1HB shall have the right to use the area marked "Easement B" as a means of ingress and egress to his or her lot by vehicular and pedestrian means, which right shall be appurtenant to such lot and shall pass with that title to such lot, subject to the following provisions:

(a) the Declarant for itself, its successors and assigns hereby covenant and agree that it shall construct, pave and maintain Easement B in the width and in the location shown on the afore said [sic] plan dated June 15, 1993, and recorded as aforesaid until lots 23HB, 25HB, 26HBR, and 27HBR inclusive are sold to individuals who reside at the premises being conveyed.

19. The Declaration under Article IV, Additional Terms Concerning Maintenance Assessments, states that:

(b) except upon dedication of the Easement B and acceptance thereof by the Town of Wrentham, neither the Association nor Board of Directors by amendment to this Declaration of Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions or otherwise [sic] be entitled to

(i) by act or omission, seek to abandon or terminate Easement B.

20. The Declaration under Article V, Subdivision of Lots, states that:

It is the intention of the Declarant that the maximum number of lots, as the term "Lot" is defined by section 81L of chapter 41 of the General Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which shall comprise the subdivision known as the Saddle Back Road Estates shall never exceed four (4). Therefore, no subdivision or resubdivision, as such terms are defined by said section 81L, shall hereafter be made of Lots 23HB, 25HB, 26HBR, and 27HBR (with the exclusion of Parcel 1HB) (as shown on Plan No. 906 and 907 of 1993 in Plan Book 418, Norfolk Registry of Deeds).

21. The Declaration under Article VII, Visual Enhancement and Agricultural Preservation, states that:

1. No building or other structure with the exception of any existing structures fences and/or corrals as hereinabove described shall be erected, constructed, placed or maintained with [sic] the area marked "Easement A" and shown on a plan entitled "Plan of Land in Wrentham Mass."

22. The Declaration references both Plan 906 and Plan 907.

23. Both Plan 906 and Plan 907 show an "Easement B" as a right of way, twenty feet wide, ending in a cul-de-sac at the northerly end, as the easement's route runs northerly from Spring Street toward Parcel 1HB, now owned by Plaintiff.

24. Plan 906 shows the cul-de-sac within Parcel 1HB.

25. Plan 907 shows the cul-de-sac terminating within Lot 27HBR before reaching Parcel 1HB; the outer circumference of the cul-de-sac is shown on Plan 907 as having, at most, a single point of tangency with the southerly property line of lot 1HB.

26. The cul-de-sac at the end of Saddleback Road or Easement B, as constructed by the Declarant, currently terminates within Lot 27HBR.

27. The owners of Lot 27HBR commissioned a survey in 2015. Based on this survey it is the understanding of defendant Kenneth MacLure that at the closest point the cul-de-sac as shown on Plan 907 is six feet and three inches away from Parcel 1HB.

28. I do not credit the accuracy of the 2015 survey. I do find, in looking at Plan 907, that the cul-de-sac established by that plan terminates in Lot 27HBR and that Easement B, as established by Plan 907, does not reach into, and does not provide a route able to afford vehicular passage into, Parcel 1HB.

29. Both Plan 906 and Plan 907 create a limited area in which to build and maintain structures, despite the large lot sizes depicted; this is because of the building restrictions in the area marked "Easement A."

30. Beginning at the eastern edge of Saddleback Road or Easement B, Plan 906 gives space to build of 200' east to west for Lot 23HB, Lot 25HB, Lot 26HB, and Lot 27HB. Each of these lots has 150' available north to south, except Lot 27HB, which has around 200' north to south.

31. Beginning at the eastern edge of Saddleback Road or Easement B Plan 907 gives 220' east to west for Lot 25HB (the portion shown), Lot 26HBR, and Lot 27HBR. It is unclear if this line is moved eastward for Lot 23HB, which is not shown on Plan 907.

32. On Plan 907 the north to south distance of the available area of Lot 26HBR is the same as for Lot 26HB on the other plan, Plan 906.

33. On Plan 907 the north to south distance of the available area Lot 27HBR is the same as for Lot 27HB on the other plan, Plan 906.

34. The Town of Wrentham Rules and Regulations Governing the Subdivision of Land ("Subdivision Rules"), which were in effect at the time Plans 906 and 907 and the Declaration were drafted, state that streets "shall not be less than forty-five (45) feet in width."

35. The Subdivision Rules also require that all streets include sidewalks on both sides of the road.

36. The road built and paved by the Declarant is twenty feet wide, except at the cul-de-sac, and has no sidewalks.

37. After the last of the four lots were sold, and the Declarant was no longer a member of the Association, Howard Bailey put a second coat of pavement on Saddleback Road, which did not extend or expand the then existing paved footprint of the road.

38. From 1996 through 2004 the Association paid Howard Bailey to plow Saddleback Road.

39. Both at the time of the Declaration and currently, Parcel 1HB had and still has frontage (of a length not known to the court) along Farm Hill Road on the western end of the lot.

40. I credit the sworn affidavit of Howard Bailey that an owner of Parcel 1HB could now build an access road from Farm Hill Road into Parcel 1HB, providing access to it from that alternative direction.

41. I understand from the sworn affidavit of John McTernan that he, as the original purchaser of Lot 27HBR, [Note 7] takes the position that he understood that the Declarant intended to use Saddleback Road to access Parcel 1HB. I am dubious about this assertion. In any event, I do not accept or find that the owners of any of the other house lots held this understanding at the time those parcels first were conveyed out by the developer, Bailey and Zahner Builders, Inc.

42. John McTernan served as counsel for Bailey and Zahner Builders, Inc. in 2006.

43. The deeds to those Defendants who are owners of Lot 23HB, 25 HB, and 26HBR each make specific reference to the Declaration as recorded in the Registry.

44. The deeds to those Defendants who are owners of Lot 27HBR state that the property conveyed is "subject to easements and restrictions of record, if any, insofar as the same are now in force and applicable." This same language is used in the deed from Bailey & Zahner Builders, Inc. to John F. McTernan.

45. I credit the sworn affidavit of Howard W. Bailey insofar as I find that one reason for creating Plan 907 was to change the lot line between Lot 26HB and Lot 27HB on Plan 906, to place an existing barn entirely on what became Lot 27HBR.

46. Defendants included as an exhibit with their summary judgment materials a copy of a single page of the Town of Wrentham Zoning Bylaw ("Bylaw"), which they averred was a true and accurate copy. While the date of that Bylaw extract was not established, I find it to be a true copy of a page of Bylaw definitions.

47. The Bylaw defines "Common Driveway" as a driveway servicing at least 2 but no more than 4 building lots."

48. Section 4.45 of the Subdivision Regulations states that "Dead-end streets shall not be longer than fifteen hundred (1500) feet."

DISCUSSION

Plaintiff's Express Easement Claim.

Plaintiff'seeks a declaration that there is an express easement appurtenant to Parcel 1HB established by the Declaration's reference to Plan 906. "The party asserting the benefit of an easement has the burden of proving its existence . . . its nature, and its extent." Martin v.

Simmons Props., LLC, 467 Mass. l, 10 (2014). "A plan referred to in a deed [showing an easement] becomes a part of the contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of the lots and to determine the rights intended to be conveyed." Hickey v. Pathways Association, Inc., 472 Mass. 735 , 754 (2015) "When the language of the applicable instruments is 'clear and explicit, and without ambiguity, there is no room for construction, or for the admission of parol evidence, to prove that the parties intended something different."' Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 25 (2006) (quoting Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. 526 (1851)). However, when ambiguity exists in the relevant instrument, it is proper to look beyond that relevant instrument. Both parties agree that additional facts are required to determine the extent of Easement B set out in the Declaration, because it points the parties to it, including the defendant members of the

Saddle Back Road Homeowners Association, and the Defendants or their predecessor owners, as well as the Declarant and its successor, the Plaintiff, to both Plan 906 and Plan 907 simultaneously, two plans which show two differing points of termination for Easement B.

I find that the Declaration itself, clearly referenced in all deeds except the deeds to Lot 27 HBR, does appear to state that, along with the four house lots, the rear land, Parcel 1HB, is to have an appurtenant right to use Easement B. I do not find, however, that the duration of this right is unambiguous-while there is no express limit on the time during which Parcel 1HB will continue to have that easement, there are reasons to think that whatever easement rights over Saddleback Road Lot 1HB might have received under the Declaration, those rights were not intended to last in perpetuity.

I note in this regard, first, that undoubtedly there is in the Declaration language cutting off the obligations of the Declarant as to Easement B upon the sale of the final of the four house parcels, and thereafter placing complete responsibility for maintenance and upkeep of the easement in the hands of the homeowners. This sunset language supports an inference of intent that the Declarant (the presumed owner of Parcel 1HB) might no longer have an interest in Easement B after the sale of the last house lot. In addition, the Declaration attaches to the transfer of the last house lot real significance concerning the control of the governance structure set up by the Declaration. When the last of the four house lots is sold, control of the Association shifts away from the developer. Before the last of the four house lots are sold, the Declarant, as a Class B member, holds five votes in associational matters, outweighing the four Class A votes allocated to the house lots. But after the last house lot is sold and then owned by the persons who are residing in the house upon it, control shifts to the Class A house lot owners.

The Declaration rests the initial responsibility and full cost of maintaining and plowing the disputed roadway on the Declarant. However, once the four house lots are sold off to thirdparty buyers, that honeymoon deal ends. From then on, the Association assumes the responsibility of caring for the roadway, and the costs are divvied up among the four lots' owners. I find this regime of great significance in determining the question now before the court-the duration and reach of the vehicle passage rights held by the back land, Plaintiff's 1HB. It is important that the Declaration does not set up a mechanism where the Declarant or any successor owner of Parcel 1HB bears any responsibility for maintenance, plowing, upkeep, or repair of Saddleback Road. I find it implausible that the Declaration would have envisioned a perpetual right of the owner of the back land to use Easement B without imposing any requirement that the Parcel 1HB owner or owners contribute over time to the cost of having the road kept up and in good, passable condition. The Declaration is careful to deal with the mechanism by which the Defendants' lots will calculate, assess, collect and expend the funds needed to keep Easement B in shape and usable, but does so by putting the total costs of that on the four lot owners--as soon as the last of those lots is conveyed out by the Declarant.

I find it supremely unlikely that the intention at the time the Declaration was created was to have the large tract of land in the back, Parcel 1HB, enjoy the unending right to drive over the disputed way without making any contribution to the ongoing cost of keeping the road maintained. This is particularly so if, as appears may be the case, the back land, measuring more than fourteen acres, might end up being divided into a number of additional house lots. If that was the contemplation in 1994, surely the Declaration would have included the necessary mechanism for those future third-party lot owners to participate in the sharing of the road costs once these additional homes on lots carved out of Parcel 1HB had been constructed and sold. The Declaration, to the contrary, sets up an arrangement for the future road costs to be shared solely among the four original lots' owners.

The central ambiguity in the reservation of the easement arises due to the unified reference to both Plan 906 and Plan 907 in the Declaration. While the plans bear different dates, both went to record on the same day, just a few weeks before the Declaration was signed. Plan 906 shows Easement B terminating within Parcel 1HB, whereas Plan 907 shows Easement B falling short of Parcel 1HB, and physically unable to connect to it, as Easement B on this plan is shown as terminating entirely within Lot 27HBR.

Plaintiff asserted in argument that the affidavit of Howard R. Bailey, in particular, cures this ambiguity by showing that the movement of the cul-de-sac in Plan 907 was simply a drafting mistake. I, however, doubt very much this simple explanation of the pivotal discrepancy between the simultaneously recorded plans. The movement of the cul-de-sac does not appear to have been a "mistake"; I find it was a carefully crafted change. Not only was the cul-de-sac moved, but the western boundary of Easement A also was moved twenty feet to the east. The dropping of the cul de sac, with its wider diameter, from Lot 1HB, down into Lot 27HBR, consumed more of the buildable area of this house lot, as first shown on Plan 906. To compensate for this, the later dated plan, Plan 907, shows a movement of Easement A, intended to give Lot 27HBR additional space to build. This seems calculated to mitigate the loss of buildable area that otherwise would have resulted from the placement of the protruding cul-de-sac on the western part of Lot 27HBR, where only a straight twenty-foot-wide easement is shown on Plan 906. The simultaneous movement of the cul-de-sac and the enlargement of the buildable area of the lot convinces me that the change in the location of the cul de sac was not a mistake. There really is nothing in the evidence, beyond the unsupported affidavit conclusions that a mistake was made in drawing Plan 907, that logically explains why that would have happened unintentionally. There is no satisfying reason why the preparer of that plan would err so dramatically by moving the entire cul de sac from one lot south to the other. To me, the change seems intentional.

I find it difficult to fault Defendants, or any person looking at the two plans, from coming to the conclusion that Plan 907 is in all respects an intentional amendment to Plan 906. To the extent the language of the Declaration cuts against this conclusion, that language has sufficient ambiguity to lead to the conclusion that the access to Parcel 1HB over Easement B that was retained by the Declarant was not intended to last beyond the sale of the fourth house lot on Saddleback Road.

The meaning of an express easement created by deed "derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances." Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007) "When created by conveyance, the grant or reservation 'must be construed with reference to all its terms and the then existing conditions so far as they are illuminating."' Mugar v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Authority, 28 Mass. App. Ct. 443 , 444 (1990) (quoting J.S. Lang Engr. v. Wilkins Potter Press, 246 Mass. 529 , 532 (1923)). "While no particular words are necessary for the grant of an easement, the instrument must identify with reasonable certainty the easement created and the dominant and servient tenements. . . . The instrument must be sufficiently precise that a surveyor can go upon the land and locate the easement. If the instrument does not describe the servient land with the precision required to render it capable of identification . . . the conveyance is absolutely nugatory." Parkinson v. Board of Assessors, 395 Mass. 643 , 645-646 (1985) (internal quotation marks removed).

The scope and location of the easement created by the Declarant for Lot 1HB's benefit is ambiguous. The production of the later plan, with a shortening of Easement B, has all of the hallmarks of an amendment. This conclusion, which I do draw, begs the question why the Declarant directed the change in the location of the cul de sac and shortening the length of Easement B.

The parties elected not to supply a complete certified copy of the Zoning Bylaw or the Subdivision Regulations applicable at the time. Limited by this, I must draw my inferences as well as I can, and only as reasonable based on the record submitted. Much can be discerned from it. The shape of the house lots are contorted to supply adequate legal frontage to each of the four of them. This was done, surely, to avoid any subdivision oversight under G.L. c. 41, §§ 81K et seq. By supplying, at least on the plans, frontage on Spring Street for each of these parcels, the plans achieved status as "approval not required" plans, earning the endorsements under G.L. c. 41, §81P which the plans bear. Parcel 1HB has its own independently sufficient legal frontage on Farm Hill Road. No subdivision was created, therefore, by the sale out of the lots shown on either plan, Plan 906 or Plan 907.

There appears, however, to have been at the time in late 1993 that these plans were put together, and the four house lots were sold off soon after, a limit on the ability to use the private way shown on the plans to service the house lots. Even though the four lots show their legal frontage as lying along Spring Street, we know that (whether for reasons of cost, wetland regulation, topography, engineering constraints, or otherwise) the true intention was that actual passage by vehicles be supplied to each of the four house lots not directly from Spring Street, but rather over the private roadway, Saddleback Road. I also infer and find that the zoning regulation in the town placed a limit on the number of homes that were entitled to be accessed by a "common driveway" such as this one-no more than four lots could, as of right, make use of Saddleback Road. Had more homes been developed on Parcel 1HB, they would have run afoul of this limitation, even if a way could have been found to supply legal frontage to these rear lots so as not to trigger the need for full-blown subdivision control approval. What likely happened is that the developer concluded that, without pursuing a definitive subdivision approval, and without obtaining relief, presumably by way of a variance, from the four-house limit on the use of Saddleback Road, the maximum number of lots on which houses easily could be built was four-the four that now are owned by the Defendants. While I recognize that in drawing these conclusions, I have needed to draw some inferences to connect together the evidence in the record, I consider them to be fair inferences. Although even without these reasonable inferences I would reach the same ultimate conclusion about the right of the Plaintiff to use Saddleback Road for the benefit of Lot 1HB, these conclusions certainly harmonize with my decision making on this central question.

More telling is the fact that neither of the plans show a roadway and easement rights which would have been legally sufficient to support a lawful definitive subdivision of the fourteen acre parcel retained by the developer, Plaintiff's Parcel 1HB. The Subdivision Rules require a road of no less than forty-five feet in width, with sidewalks alongside. If the future development of Lot 1HB required a formal subdivision (and it is difficult to see how it would not, given the size and location of that parcel, as well as the Common Driveway limit of four house lots) it defies logic that the developer would have retained an easement to benefit that back land that was materially narrower than what would be needed to get through the subdivision process when that time came. The possibility exists, of course, to secure from a Planning Board discretionary waivers from subdivision rules and regulations, see G.L. c. 41, §81R--including those governing roadway width. There is no satisfying reason, however, that the developer who drafted the Declaration would not have reserved a wider easement, at or closer to the width the Subdivision Rules required, if the intention was to develop Lot 1HB and to have Easement B provide the route in and out of that parcel. Reserving only an easement over a strip less than half the width required under the Subdivision Rules would have been a risky proposition indeed. The better inference, and the one which I draw, is that there was no long-term plan to use Easement B to serve the future development of Lot 1HB.

That does not mean that there was no intention ever to develop the remaining land to the rear. I do find, based on what has been agreed to by the parties, that Lot 1HB has frontage elsewhere, on its opposite side, over Farm Hill Road. The gaps in the record leave me without an abundance of facts to find about whether and how Lot 1HB might have been intended to be developed using Farm Hill Road as its access point. But nothing in the evidence I do have shows me that development carried out this way would be impossible. The terrain coming into Lot 1HB from Farm Hill Road may not have been as hospitable as where an access from Spring Street would enter the land. But I do not accept that the affidavits in the record require the conclusion that a development with access feeding in from Farm Hill Road would have been physically or legally unattainable. I also acknowledge that a fourteen acre parcel, even if not all of it lends itself to being built out into house lots, might require the construction of a long subdivision road, and so might run up against the Subdivision Rules' limit on the length of dead end roads-1,500 feet. I do not, however, know that a subdivision road that long would be needed. It might have been possible to have more than one curb cut on Farm Hill Road, or two distinct and shorter roads within the subdivision of Lot 1HB. I do not indulge in conjecture. What I do conclude is that, based on the evidence I do have, there is no good reason to determine that a future subdivision of Lot 1HB using Farm Hill Road as its access would have been seen in 1994 as impossible without also having easement rights over Saddleback Road. The evidence I credit does not support an inference that the Declarant would at all costs have intended to preserve full, perpetual easement for vehicular passage over Easement B for the benefit of Lot 1HB.

Ultimately, the burden of proving the express easement rests on the Plaintiff, and I find and rule that the Plaintiff has not carried that burden. I decide that the shortening of Easement B on the later prepared plan, Plan 907, was not simply a drafting error. It reflected an intention that Easement B not benefit Lot 1HB, particularly once the short amount of time necessary to sell off the four house lots had passed. While there is ambiguity arising from the way the Declaration and its incorporated plans were drafted, the better conclusion, and the one I draw, is that the recorded document does not create or reserve for the benefit of Parcel 1HB an express record perpetual right to use Easement B for vehicular passage.

Plaintiff's Implied Easement Claim.

I now turn to whether an easement by implication has arisen, which would nonetheless provide Plaintiff the passage rights it seeks. "[I]mplied easements, whether by grant or by reservation, do not arise out of necessity alone. Their origin must be found in a presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable." Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. 102 , 103 (1940). "The burden of proving the existence of an implied easement is on the party asserting it." Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006) "The burden is heavier for a grantor asserting the right to an easement by implied reservation for his benefit than for a grantee asserting such an easement by implied grant." Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 629 (1990). The scope of an easement is determined from the parties' intent, which is ascertained from the relevant instruments and the objective circumstances to which they refer. McLaughlin v. Board of Selectmen of Amherst, 422 Mass. 359 , 364 (1996), citing Butler v. Haley Greystone Corp., 352 Mass. 252 , 257 (1967). "Reasonable necessity is an important element to consider in determining if it was the presumed intent of the parties to a deed to create an easement . . . . Open and obvious use consistent with a claimed implied easement prior to a conveyance may also be a circumstance indicative of an intent on the part of the grantors and grantees to create such an easement." Boudreau, 29 Mass. App. Ct. at 630.

The burden rests on the Plaintiff to prove the existence of the easement by implication which the Plaintiff claims. Plaintiff carries the burden of proving its claimed easement under either alternative theory-whether as an express easement or as one the court will need to infer, but this burden is acute when what is in question is "the intent of the parties to create an easement which is unexpressed in terms in a deed...." Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 105 (1933). Because the touchstone of the analysis is the intention of the parties at the relevant time-here, when the Defendants' lots were conveyed out, severing ownership-for many of the same reasons that I have decided an express easement was not created at that time in the recorded Declaration and lot deeds, I also conclude there was no intention that an implied easement be reserved over Easement B for the benefit of the grantor's remaining land, Lot 1HB.

First, here there is no strict easement by necessity. I do not understand Plaintiff to contend that the conveyances of the four house lots left Lot 1HB without any available access. If that had been the case, the claim for recognition of an easement by necessity over Saddlebrook Road would have been a strong one, the law presuming that owners rarely intend to isolate the land they retain, with no way in or out. "There are cases where a single circumstance may be so compelling as to require the finding of an intent to create an easement. For example, if, after a conveyance of some of his land, an owner is left with a parcel entirely surrounded by the land conveyed, the sole fact that he has no access to the land retained without crossing the land conveyed may be sufficient basis for the implication of an easement although the deed of conveyance contains a warranty against encumbrances." Mt. Holyoke Realty Com., 284 Mass. 100 , 104. But that is not the case here. The parcel Plaintiff's predecessor continued to own is not left landlocked because of the absence of a way out over Saddleback Road. There is an alternative means of accessing Parcel 1HB from Farm Hill Road, albeit one likely costly to install. Plaintiff introduced no affidavit or professional cost estimate to show that accessing the retained fourteen acre parcel from Farm Hill Road would be so cost prohibitive as to make access over Easement B the only possible real world alternative. Nor did Plaintiff show that, given the regulations regarding subdivision and other constraints, such a road would not be possible to create. If Lot 1HB would have been rendered fully landlocked by the conveyance out of the four house lots, then an easement by necessity might be said to have arisen. But that is not what happened here.

I therefore consider Plaintiff's claim for a reserved non-express, non-record easement to be grounded, instead, in the decisional law that allows judicial recognition of an easement for passage by implication where the party asserting that right can muster sufficient proof of a "presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable." Boudreau, 29 Mass. App. Ct. at 629, quoting from Perodeau v. O'Connor, 336 Mass. 472 , 474 (1957), quoting from Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. 102 , 103 (1940).

Under this general rubric, a variety of factors advise a court in determining whether the case has been made for recognition of such an easement by implication. These factors counsel the court whether or not an occasion exists to make the ultimate required finding-that the parties at the relevant time intended such an easement for passage to be reserved.

One factor is whether, even though the easement under consideration was not established expressly, and was not strictly necessary to afford access to an otherwise landlocked parcel, the retention of the easement right would have been seen, at the time, as reasonably necessary to the contemplated use of the land for which the benefit of the implied easement is sought. "Reasonable necessity is an important element to consider in determining if it was the presumed intent of the parties to a deed to create an easement." Boudreau, 29 Mass App. Ct. at 630. In Boudreau, the court looked at whether the locus there would be landlocked without the use of the ways in contest, and concluded that that was not the case, leading to the conclusion that the parties seeking the easement "made no showing of reasonable necessity." Id. (Again, I do not understand that, if the court is inquiring into reasonable necessity, as opposed to absolute necessity, there must be proof of an otherwise landlocked parcel.) Here, there is some reason to think that preservation of a right of way over Easement B would have been, at the time of severance, of some incremental value to the owner of the retained Lot 1HB. Having a way out leading to Spring Street would not have been a bad thing, from the perspective of the developer owner of the back land. But, as I have explained in considering the Plaintiff's claim for an express easement, there was nothing then constructed on that rear land, or actively sought to be built on it at that time. From what I can tell, on the evidence I have, any development plans for that piece of property were emphemeral. And for the reasons I already have given, any use of Saddleback Road to serve house construction or other development on Lot 1HB would have been highly complicated, if not impossible, given the land use controls that would apply to the roadway needed to support that activity. I conclude that the showing of a reasonable necessity, on this record, is not well-supported.

Courts considering claims for implied easements for passage, in evaluating whether such an easement was intended at the time of severance, also look at the use then being made of the land. "Open and obvious use consistent with a claimed implied easement prior to a conveyance may also be a circumstance indicative of an intent on the part of the grantors and grantees to create such an easement." Boudreau, 29 Mass. App. Ct. at 630-631, citing Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp, 284 Mass. at 108 and Krinsky v. Hoffman, 326 Mass. at 687. Some of the implied easement cases may be read to suggest that the existence of use of the land for passage at the time of severance is an essential part of the case that must be made: "When the owner of two adjacent parcels of land retains ownership of one and conveys the other by an instrument which is silent as to a right of easement over one of the parcels for the benefit of the other, and such an easement is later asserted in court based upon an open and continuous use by the owner of one parcel for the benefit of the other at and preceding the time of the grant, if there is evidence tending to show an intent of the parties at the time of the conveyance that such an easement be then created, the question of the construction of the instrnment is presented." Mt. Holyoke, 284 Mass. at 104 (emphasis supplied).

In this case, there is no evidence that, prior to conveyance of the house lots, any use was being made of what became Saddleback Road to access Parcel 1HB. The evidence is, rather, to the contrary. The rear land was fenced off from the land out of which the house lots were created and sold off to Defendants and their predecessors. There was no gate in that fence. Passage to the rear land simply was not occurring. Lot 1HB was undeveloped, and had livestock grazing on it. This agricultural use seems to have found its access coming in from another direction, and not over the area Plaintiff now seeks to impress with an implied easement. The evidence suggests that any use of Easement B for Lot 1HB's benefit was not really made, if at all, until after the sale of the house lots on Saddleback Road. The absence of any use of the disputed passageway at and around the time of severance to serve the Plaintiff's Lot 1HB convinces me that there was no intention that an easement exist.

Even the activities undertaken by Mr. Bailey in the time after the sale of the Defendants' lots do not provide any evidence supporting the claimed easement by implication. While I accept that Mr. Bailey may have engaged for a while in maintenance, plowing, and even some resurfacing of Saddleback Road, I understand his conduct in this regard to have been as part of his legal and perceived obligations as a principal of the Declarant under the Declaration, and of the seller of those house lots. I find it significant that even though Mr. Bailey participated in the repaving of Saddleback Road, the pavement was not altered and was not extended to reach beyond Lot 27HBR. This shows that there was no understanding that the private way was to serve the larger remaining land parcel, Lot 1HB. These activities do not support a reasonable inference that Bailey was taking care of Saddleback Road for his own benefit as the holder of an easement which was appurtenant to the land in the rear.

I also do not find in the recorded instruments any good reason to infer that an unwritten easement was intended, by the parties to the 1994 Declaration and the house lot deeds, to be reserved for the benefit of Lot 1HB. As I have said, one part of the Declaration does point to the benefit of Easement B being available to serve Lot 1HB, but the better reading of the recorded instruments and plans is that no such easement was intended, at least in a way that would last beyond the third-party purchase of the last of the four house lots. Having made that finding, I see nothing in the evidence that would justify inferring the existence of a different, more expansive easement right, of perpetual duration, for use by Lot 1HB's owners. The record evidence just does not support such a finding; there was no satisfying proof that that is what the parties intended. "Implied terms cannot be imported into a conveyance because of the needs of one of the parties of which the other party has neither knowledge nor notice, or because of material facts relating to the condition of the premises known to one of the parties which the other party does not know, which he is under no obligation to know, and which he has no means of ascertaining." Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. at 104. Plaintiff did not show that Defendants (or their predecessor lot owners) knew or should have known, at the time the house lots were conveyed out, that their parcels were intended to be burdened by a perpetual easement over Saddleback Road appurtenant to Parcel 1HB. I find and rule that Plaintiff does not have an easement by implication to use any part of the Defendants' land for passage to provide access to Parcel 1HB.

Having decided that Plaintiff has not carried its burden of proving its claimed easement rights, either as a matter of express reservation in the recorded documents, or by implication, I will direct entry of a judgment that Defendants hold their fee title free of any such easement rights of the Plaintiff or benefiting its Lot 1HB.

Judgment accordingly.

BUCKS HILL REALTY, LLC v. DAVID J. GILL, STEPHEN A. SCHAIRER, GRACE D. SCHAIRER, DONNA MACLURE, KENNETH MACLURE, DONNA RICCARDI GAHAN, and RICHARD E. GAHAN, Individually and as Members of the Saddle Back Road Homeowners Association.

BUCKS HILL REALTY, LLC v. DAVID J. GILL, STEPHEN A. SCHAIRER, GRACE D. SCHAIRER, DONNA MACLURE, KENNETH MACLURE, DONNA RICCARDI GAHAN, and RICHARD E. GAHAN, Individually and as Members of the Saddle Back Road Homeowners Association.