On a thousand small town New England greens, the old white churches hold their air of sparse, sincere rebellion; frayed flags

quilt the graveyards of the Grand Army of the Republic.

Robert Lowell, "For the Union Dead" (1964)

Every town's common and village green is a physical testament to its founding. Almost always, an "old white church" sits facing the common, because most Massachusetts towns were chartered before church and state were separated in 1833. Before separation, a town was chartered in order to support a church congregation; the church congregation was the group of people who made up the town.

So it is with the town of Harwich. In the early 1740s, the residents of the southern portion of Harwich sought to form a separate precinct of the Town with its own church, or meetinghouse. By a deed dated March 8, 1743, Samuel Nickerson and Benjamin Smalley conveyed "unto the people of said precinct" a parcel of land on the north side of what is now Main Street "to lay for public uses, viz to set a meetinghouse on and also any other publick use that may be thought convenient for that neighborhood or precinct in general." A church and cemetery were built on that parcel. The portion of the parcel on which the church sits has been registered. This case concerns the adjacent cemetery.

The First Congregational Church of Harwich (Church) has brought this action against the Cemetery Commission of the Town of Harwich (Cemetery Commission) and the Town of Harwich (Town), seeking a declaration of the ownership and rights of the parties with respect to the cemetery, including an area known as the Memorial Garden, in which the cremated remains of Church members and their immediate family have been buried since 1989. The Church claims record title to the cemetery property pursuant to the 1743 deed. Alternatively, the Church claims adverse possession to the Memorial Garden and seeks a declaration that it has rights to inter the cremains of congregants and family members there. The Church also seeks injunctive relief to prevent the Town from its stated intent to disinter the individual cremains buried in the Memorial Garden and to reinter those cremains in another area in the cemetery.

The Town contends that it, not the Church, holds record title to the cemetery through the 1743 deed and that the Church did not acquire title to the Memorial Garden through a later 1899 deed or by adverse possession. The Town asserts that that it never granted the Church the right to bury cremains of congregants and family members in the Memorial Garden, and the area was to be used at most for the scattering of cremains, not interment.

This dispute has come before the court because it was discovered that some of the cremains in the Memorial Garden were interred above unmarked and unknown graves. The Town and the Cemetery Commission, rightly believing that they have a solemn duty to speak for the unknown persons interred there, seek to protect those unmarked graves by forcing the disinterment and relocation of the cremains. The Church objects, concerned about their interred congregants and the distress that disinterment would cause to family and loved ones of the deceased.

Both the Church and the Town have the same object: to honor their dead. They have brought their dispute to the court as a case stated. Based on the stated facts and drawing appropriate inferences, I find that the Church has title to the cemetery, either through the 1743 and 1899 deeds or by adverse possession, that the Cemetery Commission and Town were aware of and approved the burial of cremains in the Memorial Garden in 1989, and that, while the Town and Commission have no authority to require the disinterment and reburial of the cremains, they may require that future cremains be interred in a location in which there are not unmarked graves.

Procedural History

The Church filed its Verified Complaint on July 6, 2015, naming as defendants Cynthia A. Eldredge, Warren Nichols, Wilfred Remillard, as members of the Cemetery Commission of the Town of Harwich, and the Town of Harwich (collectively the Town). The Complaint contains four counts: Count I) Declaratory Relief pursuant to G.L. c. 231A; Count II) Quiet Title pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §§6-10; Count III) Adverse Possession; and Count IV) Declaratory Relief Rights in Land pursuant to G.L. c. 185, §1(k) and G.L. c. 231A. On September 11, 2015, the Town filed its Answer and Counterclaim. The Counterclaim contained four counts: Count I) Quiet Title; Count II) Adverse Possession; Count III) Prescriptive Easement; and Count IV) Nuisance. On September 22, 2015, the Church filed its Answer to the Counterclaim of the Town. On November 18, 2016, the parties filed a report with the court agreeing to submit this case on a case-stated basis.

On January 20, 2017, the Church filed its Statement of Facts, Motion for Judgment on Claims of Title and for Declaratory Judgment, and Memorandum in Support of its Motion for Judgment on Claims of Title and for Declaratory Judgment. On February 21, 2017, the Town filed its Cross Motion for Summary Judgment, Memorandum of Law in Support of its Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion for Summary Judgment and its Cross Motion for Summary Judgment, and the Town's Response to Statement of Material Facts of the Plaintiff and the Town's Statement of Additional Material Facts. A view was taken on March 6, 2017. On March 7, 2017, Plaintiff's and Defendants' Statements of Material Facts and Responses Thereto (SOF) and Opposition/Reply of the Church to Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment/Opposition of the defendants. On March 10, 2017, a hearing on the Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment was held where the Town waived its counterclaims of adverse possession and prescriptive easement. The case was thereafter taken under advisement.

Findings of Fact

Based on the submissions of the parties, I find the following facts as stated, after drawing appropriate inferences.

1. The Church is a duly-formed religious corporation organized under G.L. c. 180, with a regular place of business at 697 Main Street in Harwich, Massachusetts. SOF ¶ 1.

2. The Cemetery Commission is a board of the Town, consisting of three members appointed by the Board of Selectmen, with a regular place of business at 273 Queen Anne Road in Harwich, Massachusetts. SOF ¶ 2.

3. The Cemetery Commission's Rules and Regulations are not applicable to private cemeteries in Harwich. SOF ¶ 75; Exhs. 24-25, 33.

4. The Town is a duly-incorporated municipal corporation with a regular place of business of 732 Main Street in Harwich, Massachusetts. SOF ¶ 3.

5. In the early 1650's, English colonists began occupying and settling land near Cape Cod Bay in the general area known first as Harwich, later "Old Harwich" or "North Precinct," and known today as the Towns of Harwich and Brewster. During this time, residents of this area attended a meetinghouse in Eastham. SOF ¶ 5; Exh. 1.

6. As the settlement in the area of present-day Harwich grew, it became sufficient for the community to support its own minister, and in 1694 the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony granted a charter to form a town separate from Eastham, to be known as the Town of Harwich. SOF ¶ 6; Exh. 1.

7. The charter required that the Town build and maintain a meetinghouse through self-taxation. The first church in Harwich was founded in October of 1700, in the northern area of the Town. At that time, the church was known as the Church of Harwich, with no other distinguishing name. SOF ¶ 7; Exh. 1.

8. With further growth in the Town, the residents of the southern portion of Harwich sought in the 1740's to form a separate precinct of the Town with its own meetinghouse. SOF ¶ 8; Exh. 1.

9. By deed dated March 8, 1743, Samuel Nickerson and Benjamin Smalley conveyed a parcel of land on the north side of what is now Main Street for a new meetinghouse (1743 Deed). The 1743 Deed stated in relevant part:

[I]n consideration of the great need there is in this south part of Harwich of a piece of land to lay for public uses, viz to set a meetinghouse on and also any other publick use that may be thought convenient for that neighborhood or precinct in general . . . and the good will we have for said precinct and the mind to promote the publick good therein, have given, granted, enfeoffed and confirmed and by these presents do for our heirs, executors and administrators give, grant, bargain, enfeoff, confirm and deliver unto the people of said precinct a certain parcel of land situated in the said precinct or the south part of Harwich containing three acres, bounded as follows . . .

On April 17, 1747, the 1743 Deed was recorded in the Barnstable Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 22, Page 115, and subsequently on July 22, 1955 in Book 1306, Page 244. SOF ¶¶ 8, 12-13; Exhs. 1, 4, 36.

10. The grantee of the 1743 Deed was "the people of said precinct." At the time of the conveyance, a "precinct" was an ecclesiastical unit. A grant of land to the people of that precinct was to the ecclesiastical unit. SOF ¶¶ 15-17; Exhs. 2, 36.

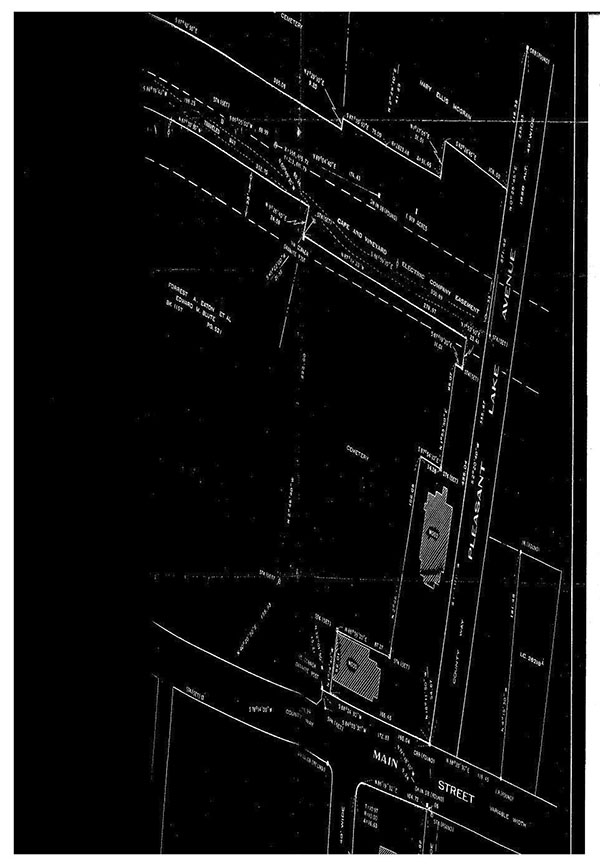

11. The 1743 Deed describes a three acre parcel at the corner of what is now Main Street and Pleasant Lake Avenue in Harwich (Property). The Property is located on the north side of Main Street in Harwich Center, there measuring 330 feet, 396 feet in depth along Pleasant Lake Avenue on the east, and 396 feet on the west boundary formerly owned by Forrest A. Eaton and Edward M. Blute. The Property is currently occupied by the Church, the Parish House, and the cemetery at issue in this case (Cemetery). The Property is depicted on a plan attached here as Exhibit A. SOF ¶¶ 4, 10-11, 14; Exhs. 3, 4.

12. The Cemetery has been known at times as the Harwich Center Cemetery, the Congregational Church Cemetery, and the First Congregational Church Cemetery. SOF ¶ 78; Exhs. 41, 46, 52.

13. On January 16, 1747, the southern portion of Harwich became a "distinct and separate precinct" of the Town, known as the Second Precinct. The Second Precinct was distinguishable from the larger township in which it was situated. SOF ¶¶ 9, 17; Exh. 2.

14. From 1747 through the present, the parcel described in the 1743 Deed has continuously been used by the Church for worship and all aspects of religious life, including burials and remembrance of the deceased. SOF ¶ 18; Exh. 1, 4-6.

15. From the earliest years of the Church, parishioners were buried in the Cemetery next to the current church building. The first burial in the Cemetery was of Ephraim Covell in 1748. Cemetery records from 1851-1874 provided by the Church purport to be records of burials of members of the Church. A large majority of those buried in the Cemetery, likely over 99%, were members of the Church. SOF ¶ 21; Exhs. 1, 5, 6, 8, 16, 21, 24, 35.

16. The original meetinghouse of the Second Precinct was constructed in 1748 in the southwest corner of the Property, to the west of the current Parish House. The original parsonage was constructed in the northeastern area of the Property, near the site of the current church. The parsonage was later moved across Main Street to its present location. SOF ¶ 19; Exh. 1.

17. The meetinghouse was originally used for both religious and secular purposes, such as holding town meetings. Attendance at the town meeting and public worship in the same building were duties of equal responsibility. Exh. 1.

18. From 1747 forward, the registry contains no deed of any portion of the Property from the Church into the Town, nor from the Town into the Church. SOF ¶ 22.

19. The original meetinghouse was taken down in 1791, and the second meetinghouse was constructed to the east of the original. Town meetings departed from the meetinghouse in 1820. After the second meetinghouse deteriorated, the structure was sold at auction in 1832. A portion of the proceeds of this sale was used "to fence in the parish graveyard." The third meetinghouse was constructed in 1832 in the northeast area of the Property. Following several modernizations, the third meetinghouse became the present church building. SOF ¶ 19; Exh. 1.

20. In 1849, after the separation of church and state, the Harwich Cemetery Association (Cemetery Association) was formed by Obed Brooks. The constitution of the Cemetery Association consists of seven articles, including one identifying officers, defining duties of the offices, and stating the Cemetery Association membership requirement"Any person making a donation becomes a member of this body, and is entitled to an engraved certificate of membership." The officers elected to the Cemetery Association include names familiar in both Church and Town records. The preamble of the constitution for the Cemetery Association states:

The Parish Burying Ground in Harwich, [c]onnected with the Congregational Meeting House, being most favorably situated for a Public Cemetery, and, on account of its antiquity, and the numbers that have been gathered there, an interesting spot to all our citizens, and to hundreds in other places whose relatives are here buried, we, the doners, wishing to preserve "the sepulchers of our fathers," and, (to many of us) the resting place of our own dust, do make a donation, to the amount specified in the accompanying certificate, (said certificate to be forwarded to the Secretary of the Harwich Cemetery Association) for the purpose of enlarging and substantially enclosing the aforesaid Burying Ground, and for otherwise improving the premises by the planting of trees and shrubbery, lying out the unoccupied portions, etc: the whole expense of which has been estimated at two thousand dollars.

The consent of the Parish having been given, we hereby form ourselves into an Association for carrying forward the above object, and adopt the following Constitution.

The Cemetery Association assumed responsibility of maintaining and improving the Cemetery for some time during the 19th Century and perhaps later. SOF ¶ 82; Exh. 20.

21. In 1857, the Congregational Parish in the Town of Harwich granted a mortgage to the Institution for Savings in the Town of Harwich. The mortgaged property is bounded as follows: "on the East and South by County Roads, on the West and North by the Congregational Cemetery, containing half an acre, more or less." The mortgage was recorded with the registry in Book 64, Page 23 (1857 Mortgage). The 1857 Mortgage did not include the Cemetery. Exh. 4.

22. In 1881, a ladies' chapel was constructed to the southwest of the church building. In 1954, the ladies' chapel was reconstructed into the current Parish House. SOF ¶ 20.

23. In 1896, the First Congregational Society of Harwich, representing the church membership during that time, was incorporated into the Church. The First Congregational Society of Harwich conveyed all church property to the newly-incorporated Church. SOF ¶ 23; Exh. 4.

24. By deed dated February 21, 1899, the First Congregational Society of Harwich granted to the newly incorporated Church, and its successors and assigns forever, "the piece of land on which the Church and Chapel at Harwich stand" (1899 Deed). The 1899 Deed describes the parcel conveyed as being bound on the north by the R.R. location (the now Church property), on the east by the Town Road (now Pleasant Lake Avenue), on the south by the Town Road (now Main Street), and "on the west by the Cemetery." The 1899 Deed was recorded on March 29, 1899 in the registry in Book 236, Page 310. The 1899 Deed does not disclose the Church's source of title. SOF ¶¶ 23-24; Exh. 4.

25. Following the 1899 Deed, there are no conveyances recorded in the registry or any other evidence of a transfer of title to the three acre parcel, or the Cemetery portion of it, to any party. SOF ¶¶ 25-26.

26. In 1938, pursuant to G.L. c. 114, § 16, Harwich Town Meeting approved a warrant article establishing a three-member Cemetery Commission and appropriated the sum of $500.00 to care for burial grounds within the town "not properly cared for by the owners." SOF ¶ 39; Exh. 15.

27. Adoption of Article 25 of 1938 Town Meeting appropriated funds and allowed the Town to begin maintenance of cemeteries identified in subsequent Town Reports as owned both by the Town and by private owners, including the Cemetery at issue here. Article 25 stated:

To see if the town will vote to raise and appropriate the sum of five hundred dollars ($500.00) to care for and keep in good order the burial grounds within the town, which are not properly cared for by the owners, under the provisions of Chapter 114; Section 16, of the General Laws, and instruct the Selectmen to have the care, and protection of such burial grounds.

Prior to 1938, the Church cared for the Cemetery. In 1938, the Church turned over care of the Cemetery to the Town. The Town has since overseen repairs and trimmed trees consistent with the Town's maintenance of the Cemetery. The Church has never withdrawn its permission to the Town for maintenance of the Cemetery. SOF ¶¶ 40-43, 45, 98; Exhs. 1, 8, 15-16, 45, 47-48.

28. In 1954, the First Congregational Church of Harwich granted a mortgage to The Cape Cod Five Cents Savings Bank. The mortgaged property is bounded as follows: "Westerly by the cemetery of the Town of Harwich, about 50 feet; Northerly by said cemetery of the Town of Harwich, 100 feet." The mortgage was recorded with the registry in Book 886, Page 259 (1954 Mortgage). The 1954 Mortgage did not include the Cemetery. Exh. 4.

29. In 1960, the First Congregational Church of Harwich granted another mortgage to The Cape Code Five Cents Savings Bank. The mortgaged property is bounded as follows: "Westerly by the cemetery of the Town of Harwich, about 50 feet; Northerly by said cemetery of the Town of Harwich, 100 feet." The mortgage was recorded with the registry in Book 1075, Page 322. The 1960 Mortgage did not include the Cemetery. Exh. 4.

30. On August 26, 1964, the Church initiated proceedings in Land Court to register title to certain portions of the Church-owned property. The Church submitted a plan with its petition entitled "Plan of Land in Harwich, Mass." dated August 10, 1964, S.R. Sweetser (Registration Plan). The Registration Plan depicts two areas for registration: Parcel 1, the land containing the Church and Parish House, and Parcel 2, the land containing the parsonage across Main Street. Parcel 2 was later severed and the subject of separate registration proceedings. The Cemetery was not included in the petition for registration. The focus of the registration petition was in the northern section of Parcel 1. SOF ¶¶ 28-30, 32; Exhs. 9-10.

31. During the registration proceedings, Attorney Henry F. Smith, representing the Church, sent a letter dated March 23, 1965, to Attorney Elliott K. Slade, representing the Town of Harwich, stating that the Church "has by passive consent allowed the Cemetery Commission to care for the Cemetery for twenty-three years." Compl., Exh. 1, sheet 11.

32. A list of abutters to Parcel 1 based on Assessor's records included the Town as owner of the Cemetery; however, a sketch contained in the Assessor's Certificate of Adjoining Owners identifies the area as "Cemetery," not "Town Cemetery" or any other label indicating Town ownership. SOF ¶ 31; Exh. 10.

33. The Certificate of Opinion returned with the Title Examination to the Land Court found the Church to have "a good title as alleged, and proper for registration" based on the 1899 Deed. SOF ¶ 33; Exh. 11.

34. Objections were filed by John White and Emma White (Whites) and by the Cemetery Commission. The objections referenced the northern area of Parcel 1 as the site of disputed rights and asserted rights in the nature of easements, not title. The Whites' objections stated that they have a right of way to pass and repass from Pleasant Lake Avenue over the Church property of Parcel 1 to access the Cemetery. The Cemetery Commissioners' objections stated that they and all persons having the right to use the Cemetery, have a right of way to pass and repass to and from the Cemetery. The Town made no claim of title to the land the Church sought to register. SOF ¶¶ 34-35; Exh. 12.

35. In response to an interrogatory by the Church regarding "the title of the Town of Harwich or the Cemetery Commissioners of Harwich in the Cemetery," the Commissioners all responded by citing to G.L. c. 114, § 16, and the Harwich Town Meeting of 1938, where the Town was authorized to care and maintain the Cemetery. Exh. 13.

36. On January 4, 1966, a trial went forward regarding the Whites' easement claims over Parcel 1. The Town and Church entered into a stipulation on that day regarding a 20-foot right of way in favor of the Town for ingress and egress in the northern area of the Church property. The stipulation states:

Petitioner may have registration as prayed for, provided decree is made subject to right of way to the Inhabitants of the Town of Harwich 20 feet in width, beginning at the Easterly sideline of Island Pond Road; Thence South 87* 30'50" East a distance of . . . 352.70 feet to a corner; Thence South 09* 26'40" West . . . 24.58 feet; For ingress and egress to the "First Congregational Church Cemetery," which adjoins Parcel 1 of Petitioners' locus as shown on the filed plan in this case.

SOF ¶ 36; Exh. 13.

37. By a decision dated March 15, 1966, the Land Court held that the Church had title to Parcel 1 free of any easement claimed by the Whites (Decision). In the Decision, the judge stated:

I find further that the respondents Emma F. White and John E. White failed to sustain the burden of proof that they or either of them have by grant, or by prescription, a right over the said area above described different from that of any member of the church, or the people of the Town or others who might wish to visit the cemetery or the church and use this area to do so. I rule that the petitioner has title to Lot 1 as shown on plan 33260A free of any encumbrance in the nature of prescriptive easement enjoyed by the respondents John E. White and Emma F. White to use the aforesaid area for passage to and from the travelled way to and from the cemetery.

The Decision referenced the Title Examiner's finding that title had been conveyed to the Church by the 1899 Deed. In describing the registered land, the Decision references bounds northerly, westerly, and southerly "all by land now or formerly by the Town of Harwich." This replaced language in the petition that did not include an owner of the land, but simply described the area being registered as "all by the Cemetery." The Decision did not address the ownership of the Cemetery property itself. SOF ¶ 37; Exhs. 10, 14.

38. Land Court Registration Plan 33260A was issued on June 2, 1966. As shown on this plan, the registered parcel contains the Church and Parish House buildings at the corner of Pleasant Lake Avenue and Main Street, but does not include the Cemetery. Ownership of the Cemetery was not adjudicated in the Land Court registration proceeding, nor has it ever been adjudicated. SOF ¶ 38; Exh. 14.

39. Church members have been buried in the Cemetery from the establishment of the Second Precinct through the present. SOF ¶ 46; Exhs. 5, 7-8, 24.

40. The Town has conducted a single burial in the Cemetery in the recent past. The Town did not seek permission of the Church to conduct the burial. SOF ¶ 48; Exh. 19.

41. Some Cemetery Commission and other Town documents refer to the Cemetery as Church property, not Town property. SOF ¶ 44; Exh. 16.

42. The Cemetery is accessible to the public and is considered a public resource. The public has never been excluded from the Cemetery. SOF ¶ 49; Exhs. 24-25.

43. In September, 1988, members of the Church began discussing the creation of a Memorial Garden for the interment of cremains of congregation members within the Cemetery. SOF ¶ 50; Exhs. 5, 22.

44. The Town Board of Health has no regulations concerning the disposal of cremated ashes. Pastor Charles Todd Newberry, III (Pastor Newberry) inquired with the Board of Health during the 1980s about interring cremains. Pastor Newberry stated that the Board told him there was no regulation about cremains and they were not concerned about them since they are considered inert. SOF ¶ 105; Exh. 8, p. 51-53.

45. A design for the Memorial Garden was prepared by G. Rockwood ("Rocky") Clark. The design contained a stone wall, bench, brick markers, and plantings. The Memorial Garden was designed for the interment of individual cremains in designated plots. SOF ¶ 51; Exhs. 5, 23.

46. The westerly abutter to the cemetery and an undertaker, Forest Eaton, raised objections to the location of the Memorial Garden in the Cemetery because he was concerned that there was a potters' field at the proposed location for the Memorial Garden, i.e., unidentified bodies buried underneath the location. SOF ¶ 92; Exhs. 8, 42.

47. Pastor Newberry and members of the Church's Board of Trustees proposed the Memorial Garden for the interment of cremains to the Cemetery Commission and the Harwich Historic District Commission. SOF ¶ 52; Exhs. 5, 8, 16, 22.

48. At a September 12, 1988 meeting, the Cemetery Commission considered the Church's proposal, described as "a cremation garden and wall with name plates" and having a "wall, decorative patio floor and planting." SOF ¶ 53; Exhs. 5, 16.

49. On November 20, 1988, the Church held a congregational meeting at which articles relating to the Memorial Garden were considered. Article I stated in part: "The Memorial Garden to be open to all members of the First Congregational Church and their immediate families for the interment of crematory ashes. . . . A donation of approximately $200.00 will be suggested for interment of the ashes." Exh. 5.

50. The Church's December 5, 1988 application to the Historic District Commission for a Certificate of Appropriateness stated the following description of the proposal: "Landscaped Memorial Garden for the interment of crematory ashes. In addition to perennial flowers and trees, there will be a 2'6" fieldstone wall, benches and terrace." The Historic District Commission looks to the proposed activity's aesthetic attractiveness in keeping with the history of the Town. SOF ¶¶ 54-55; Exhs. 5, 37, 39.

51. On December 12, 1988, Richard B. Greenman, Cemetery Commissioner/Administrator, sent a letter to Pastor Newberry noting that the Cemetery Commission voted to approve the Memorial Garden, but incorrectly stated that the Church had requested a "scattering garden." The letter referred to the site as "an area over known unmarked graves." Since Greenman's letter did not accurately reflect the proposal, Pastor Newberry called Greenman and spoke with a Mr. Doherty, the Chairman of the Cemetery Commission, who assured the Pastor of the Commission's full support of the Memorial Garden and that the Church was not violating any laws. Pastor Newberry recorded his conversation with Mr. Doherty in handwritten notes at the bottom of the December 12th letter. SOF ¶¶ 56-57; Exhs. 5, 38.

52. On December 29, 1988, the Historic District Commission approved the Church's application after public hearing. SOF ¶ 55; Exh. 5.

53. The Memorial Garden was constructed in 1989. The Garden contains a stone walkway lined with granite markers, flower bed, bronze plaques, a slate patio, bench, stone wall stone marker, sundial, shrubs, trees, and flowers. The Memorial Garden is visible from area of the cemetery, from Main Street and from Pleasant Lake Avenue. At the time of construction, the Church was aware that there may be unmarked graves in the vicinity of the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶¶ 58-60, 96; Exhs. 5, 7-8, 23, 25-26, 38, 42, 45; view.

54. Since 1989, the Church has interred the cremains of Church members and family in the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶¶ 47, 61; Exhs. 5-7.

55. Most cremains have been buried in individual plots in the Memorial Garden. Some have been buried in the cardboard boxes from the crematorium, while other have been placed in the earth directly below the stone marker. A few have been buried in urns and at least one was scattered in the flower bed of the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶ 62; Exhs. 5-7.

56. All paperwork relating to cremation and burials has always been handled by the various funeral homes involved. The interments themselves were usually performed by Mr. Blute, who also installed the markers and bronze plates for the marker stones. SOF ¶ 63; Exhs. 5- 7, 24.

57. Each interment was conducted pursuant to an agreement between the family and the Church specifying the location of the interment within the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶ 64; Exh. 29.

58. Services and interments in the Memorial Garden have always been conducted in an open and visible manner. Since 1989, 141 Church congregants and family members have been buried in the Memorial Garden. Another 50 individuals have reserved plots for future use. SOF ¶ 65; Exhs. 5-7.

59. The Church has maintained the Memorial Garden since it was constructed in 1989. SOF ¶ 66; Exhs. 8, 35.

60. At no time during the proposal or construction of the Memorial Garden, or any time until 2013, did any Town official or department assert that the Town owns the property on which the Memorial Garden is located. SOF ¶ 67; Exhs. 5-6.

61. At no time between 1989 and 2013 did any Town official or department contact the Church regarding burials in the Memorial Garden, or otherwise advise the Church that its burials were in any way improper or in violation of law or Town regulation. SOF ¶ 68; Exhs. 5- 6.

62. The Town claims it was not aware that there were interred cremains in the Memorial Garden until 2013, when the Cemetery Administrator, Robin Kelley (Kelley), began to work on getting the Cemetery listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In the process, Kelley discovered that the Memorial Garden was built over potential unmarked graves. SOF ¶¶ 74, 95, 99; Exhs. 16, 24, 40-41.

63. The Town surveyor, Paul Sweetser (Sweetser), prepared a survey of the Memorial Garden. Subsequently, Kelley conducted ground penetrating radar (GPR) of the Memorial Garden. Using Kelley's data, Sweetser drew in 31 rectangles to represent the objects found by the GPR. Kelley stated that the readings obtained in the Memorial Garden could have been bodies, but "absolutely could have been something else." SOF ¶ 100; Exhs. 40, 49.

64. Shortly after Sweetser's GPR testing, the Town retained Topographix to conduct another GPR test of the Memorial Garden. The map prepared by Topographix depicts, as individual dots, approximately 19 as anomalies with a high probability rating for unmarked burials that were located within and outside the gravel walkway as well as in the back southwest corner of the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶ 102; Exhs. 31, 40, 51.

65. The Church also retained their own GPR expert, Hager GeoScience, Inc. (Hager). Hager does not disagree with Topographix's characterization of the depicted "probable burials," but notes that further investigation would be necessary for confirmation. SOF ¶ 103; Exh. 32.

66. In 2014, the Cemetery Administrator and Commission advised the Church that the Town intended to move the Memorial Garden from its current location to another area of the Cemetery. It was explained to the Church that the 141 individuals buried in the Memorial Garden would be disinterred and reinterred in a new area of the cemetery. The Church opposed the Town's proposal. In another proposal, the Town offered to pay for the cost of the disinterment and re-interment of the cremains. SOF ¶ 69; Exhs. 6-7, 16.

67. As part of the Town's proposal to the Church, the Town intended to relocate the entire Memorial Garden including the patio, plantings, bench, wall, and other installations of the Memorial Garden to a different location in the Cemetery. SOF ¶ 70; Exhs. 6-7.

68. The Church's proposal to refrain from further burials in the Memorial Garden, while leaving existing interments intact was rejected by the Cemetery Commission. SOF ¶ 71; Exhs. 6-7.

69. Some Church members are disturbed by, and object to the forcible disinterment of family members, including parents, spouses, and children, from the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶ 72; Exhs. 6-7.

70. The Town has adopted no bylaw addressing the "reuse of occupied graves." SOF ¶ 76; Exh. 25.

71. The Cemetery Commission has not been contacted by any descendants or relatives of persons in unmarked graves buried below the Memorial Garden. SOF ¶ 77; Exhs. 24- 27.

Discussion

Because this case involves the interpretation of conveyances in 1743 and 1899 by persons who are no longer living, it was presented on a case-stated basis with the court allowed to draw appropriate factual inferences from only the available evidence and then make appropriate rulings of law. [Note 1] See Town of Ware v. Town of Hardwick, 67 Mass. App. Ct. 325 (2006); W. Mass. Theatres Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 354 Mass. 655 , 657 (1968). A case-stated arises when the parties agree on all the material ultimate facts, on which the rights of the parties are to be determined by law. Pequod Realty Corp. v. Jeffries, 314 Mass. 713 , 715 (1943); see also Frati

v. Jannini, 226 Mass. 430 , 431 (1917). A case-stated presents all pertinent facts from which the judge might draw inferences. Reilly v. Local Amalgamated Transit Union, 22 Mass. App. Ct. 558 , 568 (1986). Once the parties have submitted a case-stated, it is up to the judge to apply the law to the facts stated. Caissie v. City of Cambridge, 317 Mass. 346 , 347 (1944). Decisions, therefore, are made upon the stated facts, all inferences warranted by the facts, and the applicable law as applied to the stated facts and inferences. See Godfrey v. Mutual Fin. Corp., 242 Mass. 197 , 199 (1922); see also Town of Ware, 67 Mass. App. Ct. at 326 (any court before which a case-stated may come, either in the first instance or upon review, is at liberty to draw from the facts and documents stated in the case any inferences of fact which might have been drawn therefrom at a trial, unless the parties expressly agree that no inferences shall be drawn).

I. Record Title to the Cemetery

The first issue in this case, as framed by the parties, is whether the Church or the Town has record title to the Cemetery. The Church argues that the 1743 Deed is free of any ambiguity and evidences an intent by the grantors to convey all of their interests in the Property to the Church; the Town contends that the 1743 Deed unambiguously conveyed the Property to the Town for public purposes. Though the 1899 Deed is less clear that the Cemetery was included in the description, the Church argues that, even if not explicit, it was understood that the Cemetery was conveyed along with the land under the Church and chapel. The Town argues that the 1899 Deed to the Church did not include in its description the portion of the Property where the Cemetery lies, meaning that title to the Cemetery remained with the Town.

"A cardinal rule in the interpretation of conveyances is that every deed should be construed so as to give effect to the intent of the parties, unless inconsistent with some rule of law or repugnant to the terms of the grant." Bass River Sav. Bank v. Nickerson, 303 Mass. 332 , 334 (1939), quoting Simonds v. Simonds, 199 Mass. 552 , 554 (1908). When the words are clear, they alone determine the meaning of the instrument. Merrimack Valley Nat'l Bank v. Baird, 372 Mass. 721 , 724 (1977). Where there is no ambiguity in the instrument, it must be enforced according to its terms. Freelander v. G.K. Realty Corp., 357 Mass. 512 , 516 (1970). A clause is ambiguous if it is shown that reasonably intelligent people would differ as to which one of two or more meanings is the proper one. Jefferson Ins. Co. of New York v. Holyoke, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 472 , 474-475 (1987). However, an ambiguity is not created simply because a controversy exists between parties, each favoring an interpretation contrary to the other. Id. at 475.

Where the description in a deed fixes exactly the location of all the lines and the boundaries of the property conveyed, its construction cannot be controlled or affected by parol evidence. See Cook v. Babcock, 7 Cush. 526 , 528 (1851); Stowell v. Buswell, 135 Mass. 340 ,

345-346 (1883); Olson v. Keith, 162 Mass. 485 , 491 (1895). However, where the language of the deed is confused and ambiguous, extrinsic evidence is admissible to determine the true intent of the parties to a deed with respect to the boundaries of the land conveyed. Ellis v. Wingate, 338 Mass. 481 , 485 (1959). "[I]n cases of ambiguity in descriptions, weight may be given to the circumstances in which a conveyance was made, and to physical characteristics of the property transferred, in determining what the parties intended." Weinrebe v. Coffman, 358 Mass. 247 , 251 (1970). "Where general terms only are used to designate the subject-matter of the agreement or conveyance, or the description is of a nature to call for evidence to ascertain the relative situation, nature, and qualities of the estate, then parol evidence is not only admissible, but is absolutely essential to ascertain the true meaning of the instrument, and to determine its proper application with reference to extrinsic circumstances and objects." Gerrish v. Towne, 69 Gray 82 , 87 (1854); Jones v. Gingras, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 393 , 397 (1975) ("A latent ambiguity in the descriptions of the disputed boundary contained in the various early deeds thus arose, and this ambiguity permits the use of extrinsic evidence to show the construction given to the deeds by the parties and their predecessors in title as manifested by their acts."). I examine each deed in turn.

A. The 1743 Deed

The first issue to be decided is whether Nickerson and Smalley, with the 1743 Deed, intended to grant the Property to the Church or to the Town. The 1743 Deed provides:

[I]n consideration of the great need there is in this south part of Harwich of a piece of land to lay for public uses, viz to set a meetinghouse on and also any other publick use that may be thought convenient for that neighborhood or precinct in general . . . and the good will we have for said precinct and the mind to promote the publick good therein, have given, granted, enfeoffed and confirmed and by these presents do for our heirs, executors and administrators give, grant, bargain, enfeoff, confirm and deliver unto the people of said precinct a certain parcel of land situated in the said precinct or the south part of Harwich containing three acres, bounded as follows . . .

The parties agree that the 1743 Deed describes the three-acre parcel that today contains the Church, the Parish House, and the Cemetery. The disagreement arises in the identity of the grantee, "the people of said precinct." The Town asserts that the term "precinct" is a geographical term, and that the grantee was the municipal entity. The Town argues that the absence of a grant expressly for religious purposes and the presence of references to public uses bolsters their position that the conveyance was meant to go to the Town. The Church contends that the Property was intended to be conveyed to them based on the term "precinct," which was at the time an ecclesiastical unit, and in light of the fact that the conveyance was for the purpose of establishing a new religious society or church. To understand the meaning of the grant, I must look at its historical context.

Until the disestablishment of government-sanctioned and supported religion by an 1833 Constitutional Amendment, ratified by the Legislature in 1834, church and state in Massachusetts were united in the local organization of each colony. "All the towns originally acted . . . not only as towns but also as parishes, performing with the same organization, and by the same officers, both municipal and parochial duties." Inhabitants of Ludlow v. Sikes, 19 Pick. 317 , 322 (1837); see Tobey v. Wareham Bank, 13 Met. 440 , 446-447 (1847); Inhabitants of Milford v. Godfrey, 1 Pick. 91 , 97-98 (1822) (towns and precincts or parishes "may both subsist together in the same territory, and be composed of the same persons"). Towns could not be formed or incorporated unless they had a church, known in colonial time as a meetinghouse, which served religious as well as secular functions. Edward Buck, Massachusetts Ecclesiastical

Law, 156-157 (1866) (hereinafter Buck); William Root Bliss, Side Glimpses from the Colonial Meeting-house, 2-3, 32 (1894). Towns of the Commonwealth were thus invested with a "double capacity," making ecclesiastical and civil boundaries one and the same. Inhabitants of Ludlow, 19 Pick. at 322; Buck, at 18-19. While the town and church were one unit, they were distinct organizations or corporate bodies, each having a life of its own, but working together for the common welfare. Charles Francis Adams, Abner C. Goodell, Mellen Chamberlain, and Edward Channing, The Genesis of the Massachusetts Town and the Development of Town-Meeting Government, 60 (1892) (hereinafter Adams). No person, who happened to be a resident of the territory covered by such a parish, could be anything but a member of it. Membership attached to residence in a parish the same as citizenship attaches to residence in a city. See Kingsbery v.

Slack, 8 Mass. 154 , 157 (1811) (person liable to be taxed in western precinct where estate located, act passed only allowed attendance in the eastern precinct out of personal convenience); Carl Zollmann, Studies in History, Economics and Public Law, American Civil Church Law, 40- 41 (2008), citing Osgood v. Bradley, 7 Greenl. 441 (Me. 1831). "It was a fundamental principle that every person should contribute toward the support of public worship somewhere, be a member of some religious society, and that he never could leave one but by joining another." Inhabitants of First Parish of Sudbury v. Stearns, 21 Pick. 148 , 152 (1851).

Often, towns became too large for one church. It might be practically impossible for all of its inhabitants to worship at one place. Under these circumstances territorial parishes or precincts became a necessity, created for the express purpose of forming a new religious society or church. Exh. 2, citing Adams, at 7-8. The Church provides the affidavit of Dr. di Bonaventura for some historical background and her opinion as to the meaning behind the utilization of the term "precinct." As Dr. di Bonaventura states, and I credit, the term "precinct" referred to "an ecclesiastically determined area." Id. In other words, "a precinct and parish differ in nothing but name, both of them being corporations entitled and required to support public worship, and having all the powers and privileges necessary for that purpose." Inhabitants of Milford, 1 Pick. at 97; see Inhabitants of First Parish in Sudbury v. Jones, 8 Cush. 184 , 188 (1851). A precinct might be coextensive with a town, or it might consist of a part of the territory of a town, or it might even comprise portions taken from two or more towns. See First Parish in Brunswick v. Dunning, 7 Mass. 445 , 447 (1811); Dillingham v. Snow, 5 Mass. 547 , 554 (1809). Whatever their form or size, precincts or parishes were corporations distinct from the parent town. Town and precinct would subsist together and act apart under the management of different officers. See Dillingham v. Snow, 3 Mass. 276 , 282 (1807).

This distinction was made explicit in seventeenth and eighteenth-century colonial legislation. Article III of the Declaration of Rights of the Constitution of the Commonwealth, originating in a 1692 Act, provides that as religious jurisdictions, parishes or precincts were entitled to tax monies from precinct inhabitants for the settlement and support of ministers and religious teachers. This distinguished precincts from the larger civil township in which they were situated. Exh. 2. In 1718, the Legislature once again articulated the difference between the

precinct and the larger town with "an act more effectually providing for the support of ministers." Exh. 2. The 1718 Act stated:

And be it further enacted . . . that in all such towns where there are or shall hereafter be one or more districts or precincts regularly set off, the remaining part of such town shall be, and are hereby deemed, declared and constituted an entire perfect district, parish, or precinct, and the first or principal of said town, and the inhabitants thereof to have full power to choose a committee for the regulation and management of all affairs relating to the support of the publick worship of God, and for the choosing all necessary and proper officers in and for the said precinct, parish, or district, and further to have all such powers and privileges as by any of the laws of this province are given or annexed to any district or precinct, any law, usage or custom to the contrary notwithstanding.

With this act, the Legislature drew a distinction between towns and the precincts that were set off from the larger township. The precincts were able to be granted or appropriated property and to use it for parochial purposes, such as for a meetinghouse, minister's house, or religious burial-ground. See Inhabitants of First Parish in Sudbury, 8 Cush. at 189-190 (land granted to "inhabitants of the west precinct in S." impressed upon it a parochial character and remained property of parish upon the separation); Buck, at 151, 157. Land formerly held by the town in its parochial character would pass to the parishes as soon as they were formed. See Lakin v. Ames, 10 Cush. 198 , 215-218 (1852); Inhabitants of First Parish in Sudbury, 8 Cush. at 189; Tobey, 13 Met. at 446-447; First Parish in Medford v. Inhabitants of Medford, 21 Pick, 199, 203-204 (1838); Inhabitants of Milton v. First Congregational Parish in Milton, 10 Pick. 447 , 460-461 (1830); Inhabitants of First Parish Medford v. Pratt, 4 Pick. 222 , 236-237 (1826); See also First Parish in Boothbay v. Wylie, 43 Me. 387, 392 (Me. 1857).

This historical context supports the interpretation that the 1743 Deed was intended to grant the Property to the ecclesiastical unit, the precinct, and not to the Town. In the 1740's, the residents of the southern portion of Harwich sought to establish a separate precinct within the Town, to which residents would pay taxes to support their own meetinghouse and minister. To accomplish this, Nickerson and Smalley offered a three acre parcel of land "situated in the said precinct or the south part of Harwich" in order to "set a meetinghouse on," as well as for "any other publick use that may be thought convenient for that neighborhood or precinct in general." The Town's argument that the 1743 Deed did not use the term "church" or explicitly state that the grant was for religious purposes misunderstands the historical context of the conveyance. During the 18th Century, meetinghouse was the applicable terminology for a church or a building used for religious purposes. Woodbury v. Inhabitants of Hamilton, 6 Pick. 101 , 102 (1827). The southern precinct, approved by the General Court in 1747, was distinguishable from the Town and the grant "to the people of said precinct" was distinguishable from a grant to the inhabitants of the entire Town. The conveyance was meant only for the resident community supporting the new meetinghouse and minister, not for the Town generally. It is unlikely that the grantors intended to grant the Property to the Town, which at that time included a much larger area (what is now Brewster) and already had a meetinghouse and other lands for public use in the northern portion. The 1743 Deed's grant of the Property to the "people of said precinct" for use as a "meetinghouse" was a grant to the people of that precinct for parochial uses for their church. In other words, it was a grant to what is now the Church.

That the 1743 Deed granted the Property to the Church is further confirmed by how the Property was used after the grant. In the early 19th Century, prior to the disestablishment of state endorsed religion, courts in Massachusetts and Maine (after it was admitted to the Union and no longer part of Massachusetts) began deciding questions regarding title to lands in the town used for parochial purposes such as a meetinghouse lot. Jacob Meyer, Church and State in Massachusetts 1740-1833, 149 (1930) (hereinafter Meyer). Where a town originally took property in its parochial capacity, upon the organization of a parish, it was found that the land belonged to the parish. See The First Parish in Shrewsbury v. Smith, 14 Pick. 297 , 301-302 (1833) (upon establishment of parish, parish succeeds to all parochial property, such as the meetinghouse, and rights, duties, and liabilities of the town in its parochial affairs); Inhabitants of Milton, 10 Pick. at 460-461 (town of Milton took the land in its parochial capacity and that upon the incorporation of the parish, the parish took all the parochial rights and duties previously appertaining to the town and the land belonged to the parish). Courts ruled that property originally given to the parish or precinct remained with that parish, and therefore, if the church members seceded from the parish they could not take the property with it. See Pratt, 4 Pick at 236-237 (meetinghouse for public worship built by town before it is divided into parishes, becomes, upon such division, the exclusive property of the first parish); Eager v. The Inhabitants of Marlborough, 10 Mass. 430 (1813) (meeting-house remained property of the first parish in Marlborough after a number of the inhabitants were incorporated and made "the second parish in Marlborough", though debts of a parochial nature due before a division for services for the general benefit remain chargeable upon the town); see also Richardson v. Brown, 6 Me. 355, 357 (Me. 1830) (when one or more parishes shall be set off from a town, the remaining part shall constitute the first parish); Meyer, at 177, 183; Buck, at 52. Control of property that was originally granted to a parish by the town for religious purposes was retained by the parish so long as it was used in a parochial capacity.

When church and state became separated in Massachusetts in 1833 by Constitutional Amendment, ratified by the Legislature in 1834, several disputes arose over whether property originally conveyed to the town or precinct was retained by the town or the precinct. The courts generally resolved these disputes by looking to how the property was used. "An appropriation to a municipal or parochial use during the union, would determine whether it was town or parochial property at the time of the formation of the new parish, and the consequent separation of the town and the original parish into two distinct corporations. Such appropriation, when distinctly made, would be equivalent to a grant of the property to a specific use." Lakin, 10 Cush. at 218-220. Courts consistently maintained that the parish was legally entitled to the church property that had previously been appropriated to it if it was still in its possession and continued to be used for religious purposes. See The Inhabitants of the First Parish in Sudbury, 8 Cush. at 189 (property originally granted to inhabitants of precinct "retained that [parochial] character, whilst the corporation exercised the functions of both town and parish; and that upon the separation it remained the property of the parish"); Tobey, 13 Met. at 446 (the "principle is now well settled, that where lands are holden by the town in its parochial capacity, the proceeds of the sale of such lands are also holden by the town in the like capacity; and upon the separate organization of a parish, the parish succeeds to all the parochial property of the town"); Meyer, at 181, 183, 200, 220. In general, courts held that a parish is a public corporation quite as old and valuable as the town itself and that a parish is not to be deprived of its lawful property once acquired by any use which it may permit the town or others to enjoy for a series of years. See First Parish in Woburn

v. Middlesex County, 73 Mass. 106 , 108-109 (1856) (parish may recover against the county for the diminution of the value of land granted to the town for parochial purposes resulting from a taking); Bachelder v. Wakefield, 8 Cush. 243 , 251-252 (1851) (parishioner could not claim adverse possession of a portion of the common land for his horse shed when it was given with permission of the parish); Inhabitants of Ludlow, 19 Pick. at 326-328 (proceeds from sale of land conveyed to town for use of ministry go to town in its parochial capacity because the "parish, when organized, succeeded to all the parochial property, rights, duties, and liabilities of the town, and consequently became the legal owners of the [promissory] notes in question"); Buck at 153.

On the other hand, when land originally appropriated for parochial uses was no longer used for religious purposes but rather municipal purposes, or the grant was not exclusively for parochial purposes, courts held that subsequent to disestablishment, the property belonged to the town. See Packard v. First Congregational Parish in Duxbury, 256 Mass. 550 , 554 (1926) ("While it is well settled that upon separation the parish was entitled to land which had been appropriated and used for parochial purposes, yet land, the use of which for such purposes had finally ended during the dual relationship, remained the property of the town."); Orthodox Congregational Soc'y of Greenwich v. Inhabitants of Greenwich, 145 Mass. 112 , 114 (1887) (where town kept old custom of ringing bell in meetinghouse at noon and tolling it when deaths occur, and has always had access to the vestibule of the meetinghouse for those purposes, without evidence that this was by the permission of the congregational society, the town acquired adverse possession for this daily use); Inhabitants of Princeton v. Adams, 10 Cush. 129 , 132-133 (1852) (where property is given to church "so long as they maintain their present essential doctrines and principles of faith and practice," which were then Unitarian, is forfeited by change to Trinitarian system of faith and practice); Lakin, 10 Cush. at 218-220 (property does not revert to the original parish upon subsequent division into parishes, if the property has been exclusively appropriated to the use of the town in its municipal capacity); Stearns v. Woodbury, 10 Met. 27 , 31-32 (1845) (absent evidence of an appropriation or dedication of lands to the uses of parishes, the parish did not have title to property of burying ground); Inhabitants of Second Precinct in Rehoboth v. Carpenter, 23 Pick. 131 ,136-138 (1839) (where a new society was incorporated and entered upon and took possession of lands formerly granted to a parish, and remained in possession for more than 30 years, during which time the parish had no meeting and exercised no corporate powers, parish was disseized, and right of entry tolled by long-continued adverse possession); see First Parish in Boothbay, 43 Me. at 393-395 (not enough evidence that the property was specifically set apart for parish use exclusively).

Here, the Property, in particular the Cemetery, has been used by the Church for worship and all aspects of religious life, including burials in the Cemetery and remembrance of the deceased, from 1747 to the present. Exhs. 3, 5-6. The original meetinghouse of the precinct was constructed west of the current Parish House, in the southwest corner of the now Cemetery. Exhs. 1, 9. Until the separation of church and state, the meetinghouse was used for a place where the townspeople met to discuss and settle all affairs, both secular and religious. Attendance at the town meeting and public worship in the same building were duties of equal responsibility. Exh. 1. The first meetinghouse was taken down in 1791, and a second was constructed east of the original. Town meetings departed from the meetinghouse in 1820. Exh. 1. After the second meetinghouse deteriorated, the structure was sold at auction in 1832. A portion of the proceeds of this sale was used "to fence in the parish graveyard." Exh. 1. The Church also maintained the Cemetery during this time. Exh. 8. From the earliest years of the Church, parishioners were buried in the Cemetery to the west of the current church building and north of the current Parish House. The first burial in the Cemetery was of Ephraim Covell in 1748. Exhs. 16, 24. Almost all of those buried in the Cemetery are members of the Church. Exhs. 8, 24. Cemetery records from 1851-1874 provided by the Church purport to be those of burials of members of the Church. [Note 2] Exhs. 21, 24, 35. The constitution of the Cemetery Association, an entity that maintained the Cemetery during some part of the 19th Century, acknowledged that the Cemetery Association was formed with the "consent of the Parish," an indication that the Church owned and controlled the Cemetery. Exh. 20. The evidence in the record shows, and I find, that the historical use of the Cemetery by the Church was for parochial, not municipal, purposes both before and after the separation of church and state. In short, the 1743 Deed conveyed the Property to the Church and not the Town, and the Church retained control of and continued to use the Cemetery for parochial purposes after the disestablishment of religion in 1834.

B. The 1899 Deed

The second issue is whether the 1899 Deed conveyed the Cemetery to the Church. After the Church was incorporated in 1896, the First Congregational Society of Harwich, representing church membership and holding church property, conveyed church property to the corporate entity in a series of deeds. Exh. 4. By the 1899 Deed, the First Congregation Society of Harwich granted to the First Congregation Church of Harwich Mass., Inc., "the piece of land on which the Church and Chapel at Harwich stand." The 1899 Deed describes the parcel as being bound on the north by the RR location (now Church property); on the east by the Town Road (now Pleasant Lake Avenue); on the south by the Town Road (now Main Street); and "on the west by the Cemetery." Exh. 4. The 1899 Deed provides no acreage, courses, or distances. The parties agree that the 1899 Deed at least includes the portion of the Property on which the Church and chapel were located in 1899, and where the Church and Parish House are located today. The question is whether the language bounded "on the west by the cemetery" was intended to convey the Cemetery as well as the Church and chapel area, or whether it excluded the Cemetery from the conveyance.

Although the language of the 1899 Deed is not explicit, the evidence supports the finding that the conveyance was intended to include the Cemetery along with the other property of the Church. The Cemetery was in fact part of the Property that was granted to the second precinct in 1743 for such parochial purposes, along with two other adjacent parcels of land on which the Church and chapel were built. There is no record of the Cemetery being severed from the land under the Church and chapel. The Cemetery had since been treated and dealt with in common with the other abutting church properties. Evidence in the record shows frequent, repeated, continued and unquestionable acts of ownership and control, on the part of the Church, of all of the Property including the Cemetery, leading up to the 1899 Deed and thereafter. Cemetery records indicate burials of church members took place throughout the 1800s. The meetinghouse was moved several times to different portions of the three-acre Property, including the area of the Cemetery. In addition, the Cemetery was fenced in during the 1830s with the proceeds from the sale of the second meetinghouse, enclosing the Cemetery along with the other Church buildings and property. It can hardly be supposed that the First Congregational Society of Harwich, representing church membership, intended to give to the newly incorporated Church only partial title to the Property and withhold from the Church a right to their Cemetery, somehow retaining rights among the unincorporated group of church members. Under the circumstances, the Church likely understood and intended the Cemetery to be conveyed with the land under the Church and chapel since families and ancestors of the Church had been buried there and would continue to be interred. I find that the 1899 Deed conveyed the Cemetery to the Church.

II. The Maintenance Agreement

Following the 1899 Deed, there are no conveyances recorded in the registry or any other evidence of a transfer of title to the Property or the Cemetery portion. In 1938, the Town assumed responsibility for maintenance of the Cemetery, along with a number of other private cemeteries in Harwich, pursuant to G.L. c. 114, § 16. The Town argues that its assumption of maintenance obligations for the Cemetery constituted a transfer of title to the Cemetery. This claim fails. The Town's maintenance of the Cemetery is not based on ownership, but permissive statutory authority for a municipality to care for neglected burial grounds.

Among the many effects of the Great Depression was that owners of private cemeteries were often unable to care for them, letting the cemeteries fall into neglect and ruin. Exhs. 1, 8. The Legislature enacted G.L. c. 114, § 16, in 1938 to address this problem. Section 16 provides:

Any town may annually appropriate and raise by taxation such sums as may be necessary to care for and keep in good order and to protect by proper fences any or all burial grounds within the town in which ten or more bodies are interred and which are not properly cared for by the owners, and the care and protection of such burial grounds shall be in charge of the cemetery commissioners, if the town has such officers, otherwise in charge of the selectmen.

G.L. c. 114, § 16 (emphasis added). The language of the statute makes clear that cemeteries cared for by the Town are not municipally owned, but owned by others. The authority granted by this statute was explicit that it was for a municipality to assume caretaking responsibilities for cemeteries owned by others. Town-owned cemeteries were already under the care of and maintained by the municipality. Acting pursuant to § 16, the Town in 1938 approved warrant articles establishing a three-member Cemetery Commission and appropriating $500 to care for burial grounds within the Town "not properly cared for by the owners." Exh. 15. The adoption of Article 25 allowed the Town to undertake maintenance of the cemeteries identified in subsequent Town reports, including the Cemetery adjacent to the Church. Pursuant to such authority, the Town has continued to care for the Cemetery since that adoption in 1938.

The evidence demonstrates, and I find, that this care has always been with the permission and consent of the Church, which has never been withdrawn. Exh. 1 ("During the leaner years now gone the church turned over the responsibility for care of its old cemetery to the Town.").

When the Church petitioned for two portions of the Property containing the church and Parish House buildings to be registered in 1964, the attorney representing the Church stated in a letter to opposing counsel that the Church "has by passive consent allowed the Cemetery Commission to care for the Cemetery for twenty-three years." Compl., Exh. 1, sheet 11. Records of the Town and Cemetery Commission frequently refer to the Cemetery as the "Congregational Church Cemetery" or "Congregational Church Cemetery of Harwich Center" and recognize it as being privately owned. [Note 3] Exhs. 15, 16. These documents show that the Town understood the Cemetery to be privately owned and that it was only undertaking maintenance of the area while ownership remained with the Church. The Cemetery remained with the Church in accordance with the 1743 Deed and 1899 Deed and the Town's permissive caretaking did not give it record title to the Cemetery.

III. Adverse Possession and Prescription

The Town argues alternatively that it has acquired title to the Cemetery by adverse possession. "Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years." Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). "All these elements are essential to be proved, and the failure to establish any one of them is fatal to the validity of the claim. In weighing and applying the evidence in support of such a title, the acts of the wrongdoer are to be construed strictly, and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof of an actual occupancy, clear, definite, positive, and notorious." Cook, 65 Mass. at 209210. "If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pennsylvania, 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968). The test for adverse possession is the degree and nature of control exercised over a disputed area, the character of the land, and the purposes for which the land is adapted. Ryan, 348 Mass. at 262. The claimant must demonstrate that it made changes upon the land that constitute "such a control and dominion over the premises as to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership." Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556, quoting LaChance v. First Nat'l Bank & Trust Co. of Greenfield, 301 Mass. 488 , 491 (1938). "The burden of proof in any adverse possession case rests on the claimant and extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession." Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 847 (2004).

The Town claims to have held and used the Cemetery property for at least 200 years for public burials and that during that time the Town has maintained the Cemetery property. Prior to the 1938 Town Meeting and adoption of Article 25, there is nothing showing that the Town used the Cemetery in any manner. In fact, evidence in the record shows frequent, repeated, continued, and unquestionable acts of ownership and control over the Cemetery on the part of the Church. As previously noted, the 1743 Deed was to the newly established second precinct, which constructed its own meetinghouse and parish house, hired its own minister, and began burying deceased church members in the Cemetery adjacent to the church. Cemetery records indicate burials of church members took place throughout the 1800s. The Cemetery was also fenced in during the 1830s by the Church with the proceeds from the sale of the second meetinghouse.

As discussed, a separate entity, the Cemetery Association, assumed responsibility of maintaining the Cemetery for some time during the 19th Century and perhaps later. To the extent that the Town claims this organization to be a municipal entity and evidence of Town taking care of the Cemetery, the evidence concerning the Cemetery Association does not support this contention. The Cemetery Association was a private organization, not one formed by the Town. Municipal boards and departments are not formed in the above manner, nor are they governed by such a constitution. Municipal bodies do not grant membership or supply engraved certification upon the receipt of donations. While the relationship between the Cemetery Association and the Church is not entirely clear, there was overlapping membership between the Church and the Association, the Association's constitution stated that it was founded with "the consent" of the Church, and the Church's records include documentation of matters involving the Cemetery Association. Whatever its relation to the Church, it is evident that the Cemetery Association was not an entity of the Town. It is unclear how long the Cemetery Association conducted business and cared for the Cemetery. What is certain is that by the late 1930s it appears neither the Cemetery Association or the Church was actively maintaining it.

The earliest that the Town can show use of the Cemetery is 1938, when the Town adopted Article 25 and commenced caring for the Cemetery. The Church does not dispute that the Town has cared for the Cemetery since that time and continues to mow, trim branches, and make repairs to structures on the Cemetery. Exhs. 47-48. What the Church does contest is that the activities conducted by the Town on the Cemetery demonstrate the Town's adverse possession of the Cemetery. The Town has failed to show exclusive or adverse use. Though the Town performed maintenance tasks on the Cemetery, these were not to the exclusion of the Church. During the entire maintenance period, the Church has continued to conduct burials within the Cemetery. Church members and the public have continued to use the Cemetery, traversing it to visit burial sites. The Town has never attempted to exclude other parties from using the Cemetery. Thus, the Church has never been disseized of the Cemetery property.

Moreover, the Town's caretaking actions were always with the permission of the Church. The Church deliberately turned over care of the cemetery to the Town under G.L. c. 114, § 16, when it could no longer afford to maintain it itself. There is no evidence that the Church withdrew its permission to the Town at any time. The Town has produced no evidence suggesting that their maintenance and related activities have been exclusive or non-permissive since the Town began to far care for the Cemetery. The Town has failed to carry its burden of proof on these elements of adverse possession and cannot prevail on this claim.

The Town alternatively claims to have acquired a prescriptive easement in the Cemetery. To establish a prescriptive easement, a party must prove open, notorious, adverse, and continuous or uninterrupted use of the servient estate for a period of not less than twenty years.

G.L. c. 187, § 2; Ryan, 348 Mass. at 263; Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 835 (2008); Long v. Woods, 22 LCR 416 , 420 (2014). In other words, it requires the same showing as a claim for adverse possession, except proof of exclusive use. Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44, n. 9 (2007). "Whether the elements of a claim for a prescriptive easement have been satisfied is a factual question for the trial judge," and the party who claims a prescriptive easement bears the burden on every element. Denardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 363 (2009); Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. As discussed above, the Town is unable to establish that its caretaking of the Cemetery was adverse to the Church. The Church voluntarily turned over the maintenance of the Cemetery to the Town and the Town continued to maintain it since that time with the permission of the Church. At no time did the Church revoke the permission given to the Town. For the reasons stated, the Town has also not acquired a prescriptive easement in the Cemetery.

IV. The 1964 Registration

In 1964, the Church initiated registration proceedings in Land Court to register title to two parcels of the Property containing the church and Parish House buildings at the corner of Pleasant Lake Avenue and Main Street. The Town asserts that because the Church did not petition to register the area containing the Cemetery, the Church did not believe it had title to that area. The Church contends that seeking registration of only those two parcels of land and not the Cemetery was motived by resolving conflicts that did not involve the Cemetery area and was not an indication that the Church did not own the Cemetery. The Church's contentions are supported by the evidence.

On August 26, 1964, the petition for registration of the Church's property was filed in the Land Court. The Registration Plan was submitted along with the petition. The Registration Plan depicts two areas for registration: Parcel 1, the land containing the Church and Parish House, and Parcel 2, the land containing the parsonage across Main Street. Parcel 2 was later severed and became the subject of separate registration proceedings. The Cemetery was not included in the petition for registration, but is depicted on the Registration Plan as "Cemetery."

The Certificate of Opinion returned with the Title Examination to the Land Court found the Church to have "a good title as alleged, and proper for registration" based on the 1899 Deed. Exh. 11. Objections were filed to the petition by John and Emma White, and by the Town of Harwich Cemetery Commissioners. The area in dispute was the northern area of Parcel 1, and both the Whites and the Cemetery Commissioners asserted rights in the nature of easements in that area. Exhs. 9-10. The Whites' objections stated that they had a right of way to pass and repass from Pleasant Lake Avenue over the Church property of Parcel 1 to access the Cemetery. The Cemetery Commissioners' objections stated that they and all persons having the right to use the Cemetery had a right of way to pass and repass to and from the Cemetery. Exh. 12. A list of abutters to Parcel 1 based on Assessor's records included the Town as owner of the Cemetery; a sketch contained in the Assessor's Certificate of Adjoining Owners, however, identifies the area as "Cemetery," not "Town Cemetery" or any other label indicating Town ownership. SOF ¶ 31; Exh. 10. Further, in response to an interrogatory by the Church regarding "the title of the Town of Harwich or the Cemetery Commissioners of Harwich in the Cemetery," the Commissioners all responded by citing to G.L. c. 114, § 16, and the Harwich Town Meeting of 1938, where the Town was authorized to care and maintain the Cemetery, as the source of the Town's alleged title. Exh. 13.

On January 4, 1966, a trial was held on the Whites' easement claims over Parcel 1. On the day of the trial, the Cemetery Commissioners entered into a stipulation regarding a 20-foot right of way in favor of the Town for ingress and egress in the northern area of the Church property. Exh. 13. In its Decision dated March 15, 1966, the Land Court held that the Church had title to Parcel 1 free of any easement claimed by the Whites "to use the aforesaid area for passage to and from the travelled way to and from the cemetery." Exh. 14. In describing the registered land, the Decision referenced bounds northerly, westerly, and southerly "all by land now or formerly by the Town of Harwich." This replaced language in the petition that did not include an owner of the land, but simply described the area being registered as "all by the Cemetery." Exhs. 10, 14. The Decision referenced the Title Examiner's finding that title had been conveyed to the Church by the 1899 Deed. The Decision did not address the ownership of the Cemetery property itself. Exh. 14. The Land Court Registration Plan 33260A was issued on June 2, 1966. As shown on this plan, the registered parcel contains the Church and Parish House buildings at the corner of Pleasant Lake Avenue and Main Street, but does not include the Cemetery. Exh. 14.

Though the Town suggests that the Church did not petition to register the Cemetery area because it did not have title to that portion of the Property, the evidence does not support such a conclusion. The Church's concerns at the time were centered on the easement claims by the Whites and the Cemetery Commissioners in the northeast area of Parcel 1. The Land Court decree was sought only to extinguish those claims. The Church had no reason to seek a declaration that the Cemetery adjacent to the Church belonged to the Church since there was no adverse claim of ownership to that area. The Church also had no interest in preventing any person from passing and repassing through the Cemetery. In fact the letter from Attorney Smith, counsel to the Church during the registration proceedings, to Town counsel where he states that the Church "has by passive consent allowed the Cemetery Commission to care for the Cemetery for twenty-three years," indicates that the Church did believe it owned the Cemetery and as an owner had granted the Town permission to maintain it. Compl., Exh. 1, sheet 11.

In addition, the Church historically treated the Cemetery parcel differently than the two registered parcels. Several times over the years, the Church mortgaged portions of the Property adjacent to the Cemetery. The 1857 Mortgage, 1954 Mortgage and 1960 Mortgage all describe the mortgaged property as bounded by the Cemetery, in the areas where the Church buildings were located. Exh. 4. Owners of multiple parcels are not required to register all their property. The fact that the Cemetery was not included in the petition for registration is not, in and of itself, an indication that the Church lacked title to the Cemetery, nor is it proof that title lay with the Town.

That the Decision changed the language of the description of registered land from "all by the Cemetery" to "all by land now or formerly by the Town of Harwich," also does not demonstrate that the Town had record title to the Cemetery. In the original registration plan

submitted by the Church, it simply labeled the area "Cemetery," with no description referring to it as a Town Cemetery. In the interrogatories sent to the Commissioners and the Whites, the Church never refers to the Cemetery as being owned by the Town. In fact, the interrogatories question the Town's source of its claim of superior title to the Cemetery. Though it is uncertain why the Church did not object to the description of the registered land in the Decision of "by land now or formerly by the Town of Harwich," the Church's failure to do so is not relevant to determining title to the Cemetery. Ownership of the Cemetery was not adjudicated during the registration proceedings. The only legal conclusion reached was that the Church had good title to the two parcels it sought to register. As shown on the Land Court Registration Plan 33260A, the registered parcel contains the Church and Parish House buildings at the corner of Pleasant Lake and Main Street, but not the Cemetery.

V. Adverse Possession of the Memorial Garden

I have found that the Church has record title to the entire Cemetery, and that the Town's adverse possession and prescriptive easement claims do not divest the Church of its title to the Cemetery. Alternatively, I find that the Church has acquired title by adverse possession in the Memorial Garden area of the Cemetery through its nonpermissive use which was actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for over 20 years. See Ryan, 348 Mass. at 262.