ANTHONY JAMULA as personal representative of the Estate of Michael Jamula, STEPHEN HARRIS, and GITA JOZSEF (HARRIS) v. TOWN OF MIDDLEFIELD, JANINE SAVOY, STEVEN SAVOY JR., TIMOTHY PEASE, ANTHONY KUNASEK, LINDA KUNASEK, LEO VARSANO, CAROL VARSANO, GEORGE HAYWOOD and DENISE HAYWOOD.

ANTHONY JAMULA as personal representative of the Estate of Michael Jamula, STEPHEN HARRIS, and GITA JOZSEF (HARRIS) v. TOWN OF MIDDLEFIELD, JANINE SAVOY, STEVEN SAVOY JR., TIMOTHY PEASE, ANTHONY KUNASEK, LINDA KUNASEK, LEO VARSANO, CAROL VARSANO, GEORGE HAYWOOD and DENISE HAYWOOD.

MISC 12-462859

June 7, 2018

Hampshire, ss.

LONG, J.

DECISION

Introduction

At issue in this case are the plaintiffs' rights, if any, to access their woodlands in Middlefield by going through the individually-named defendants' privately-owned lands. The route whose use they seek is on the remaining vestiges of two former dirt roadways, once but no longer public, that were taken in easement by town meeting votes in 1780 (the first roadway) and 1805 (the second), laid out by the town, fell into disuse by the mid-1800s, and were discontinued by town meeting vote in 1886. Thereafter, in the sections at issue in this lawsuit, they were gated off and their underlying land re-integrated into the fee owners' properties. Those owners today are the individually-named defendants.

The plaintiffs do not need this access. Plaintiff Jamula's property abuts Chester Road and Alderman Road, both public, and has its own internal ways, entirely on that property, that can provide access to all parts of that land from those public roads. The Harris plaintiffs' property abuts Johnnycake Hill Road, also public, and it too has its own internal ways, entirely on that property, that can access all parts of that land from that public road. The plaintiffs want access by this route, however, because they believe they have a right to it and because it would be easier for their logging operations - less of an uphill climb for the Harris' log trucks compared to the access over their own land and, for Mr. Jamula, avoiding the need to improve his internal ways with a new stream crossing or, alternatively, use smaller logging equipment. [Note 1] It would also more directly access the site where Mr. Jamula currently has a small hunting shack and has considered building something larger and more permanent.

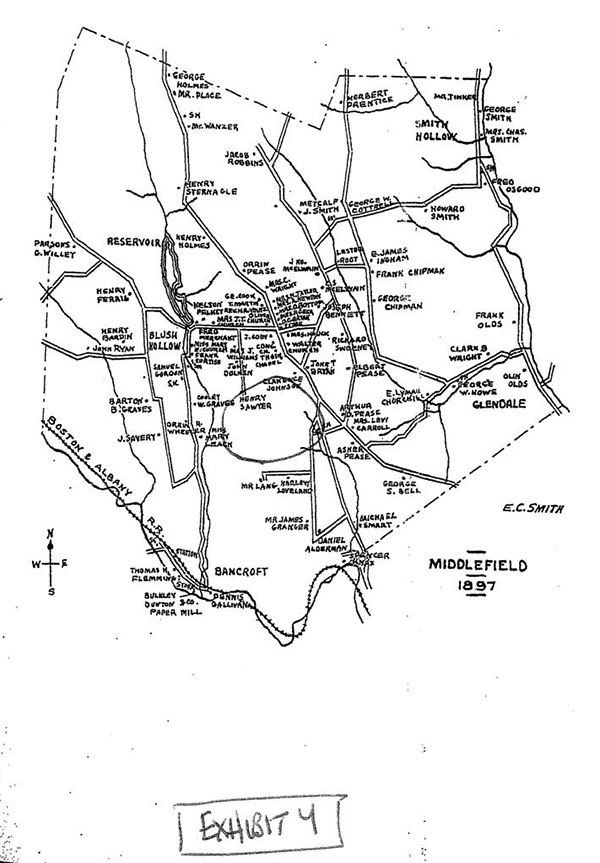

The 1780 and 1805 town meetings took the roadways in easement and, in the sections at issue in this lawsuit, laid them out in locations where there had been no roads before. [Note 2] Because the roadways were taken in easement rather than fee, the owners of the land on which they were located retained the fee ownership of the underlying roadbeds in their respective sections. When the public easement ended in 1886, those roadbeds returned to the full control of their respective landowners, free of everything but private rights, if any. See Nylander v. Potter, 423 Mass. 158 , 161 (1996). Both of these roadways were removed from the town's road maps by 1897 at the latest. To the extent they still appeared as roadways on the tax assessor's map, showing them as roadways was (and is) erroneous. [Note 3]

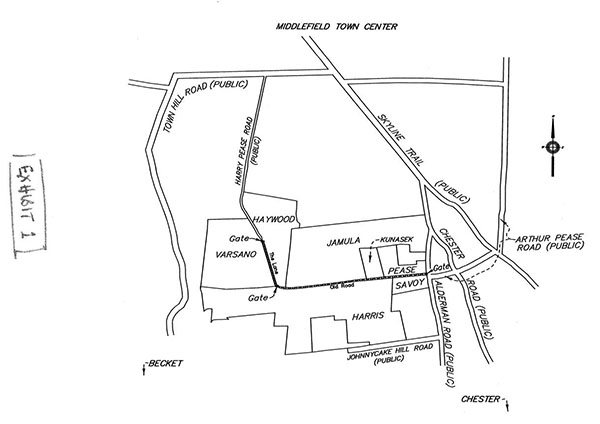

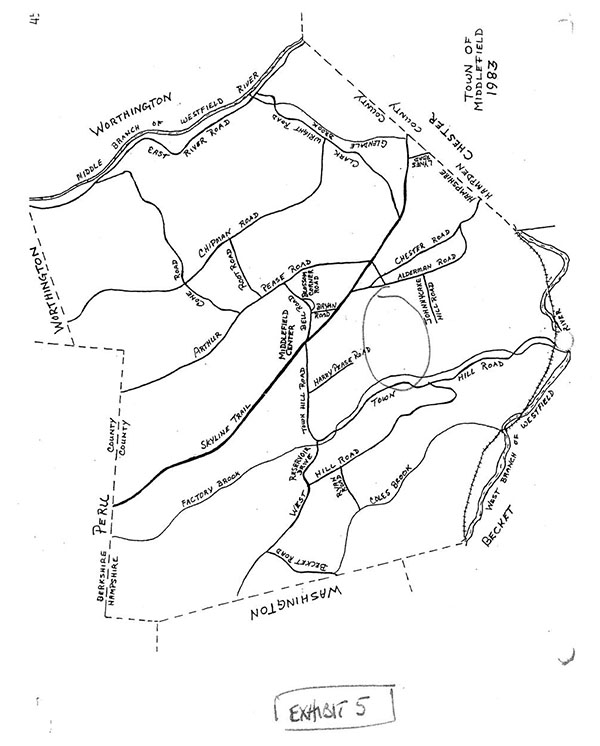

To make the narration in this Decision easier to follow - in particular, to enable the reader to have the various locations it references accurately in mind as the narration proceeds - a sketch of the area is attached as Ex. 1.

The area on that sketch labelled "The Lane", currently owned by the Varsano and Haywood defendants (each to its midpoint on their respective sides), was part of the 1780 taking and discontinued in 1886. The non-discontinued, still-public part of that taking (Harry Pease Road, which stops at the top of the Lane) ended where it did because there were no homes beyond that point, and because whatever use the discontinued part had once received for access elsewhere had long-since been superseded by the main public roads - Skyline Trail, Chester Road, Alderman Road, and Town Hill Road - that were, and are, far more direct and convenient. See Ex. 1. The Lane was gated off at both ends after the 1886 discontinuance, fenced in by the Varsanos' and Haywoods' predecessors, and thereafter used exclusively by those properties as an integrated part of their pastureland.

The area labelled "Old Road" was part of the 1805 taking. It too was discontinued by the 1886 town meeting vote (other sections, including its former link to Town Hill Road and thence to Becket, had already been abandoned by that time), and for much the same reasons. There had only ever been one home along it (the Henry Hawes house) which, by 1886, was no longer inhabited, [Note 4] and with its connection to Town Hill Road long gone, it no longer lead anywhere. It too was gated off after the discontinuance, integrated into its roadbed owners' lands, used by them for grazing and a cowpath, and was impassable in wet weather.

It is now 130 years after the discontinuance. For the reasons noted above, both the Jamulas and the Harrises, relatively recent purchasers of their properties, want to use Old Road for additional access to Alderman Road, and to use the Lane for access to Harry Pease Road.

They cannot do so without going through the Pease, Savoy and Kunasek properties to their east, and the Varsano and Haywood properties to their north. See Ex. 1. In support of their claim of access, they make the following arguments.

First, despite the 1886 town meeting vote to discontinue these roadways - a vote that was reviewed, ratified and affirmed as a full discontinuance by subsequent town meeting votes in 1984 and 2012 [Note 5] - the plaintiffs contend that both the Lane and Old Road remain public or, if not public, subject to public access. More precisely, they contend that (1) the 1886, 1984 and 2012 votes did not discontinue the roadways' public status, only the public obligation to maintain them, and (2) even if the roadways were discontinued, the public subsequently acquired access rights by prescription. In the alternative, should the court find that no public right of access still exists, the plaintiffs contend that their properties have appurtenant private rights of access over both of the former roadways either by necessity, prescription, or express or implied in their deeds. For use in a pending Superior Court action, they also request a declaration of when the roadways' public status ended, and the Superior Court has deferred to this court to make that determination.

The individual defendants deny that the plaintiffs have any right, public or private, to pass over any part of their properties. For its part, the town denies that either of the former roadways is presently public, [Note 6] and takes no position on the existence or non-existence of the plaintiffs' alleged private rights.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule as follows.

Facts and Analysis

These are the facts as I find them after trial, and the rulings of law I make based on those facts.

The Area in Dispute

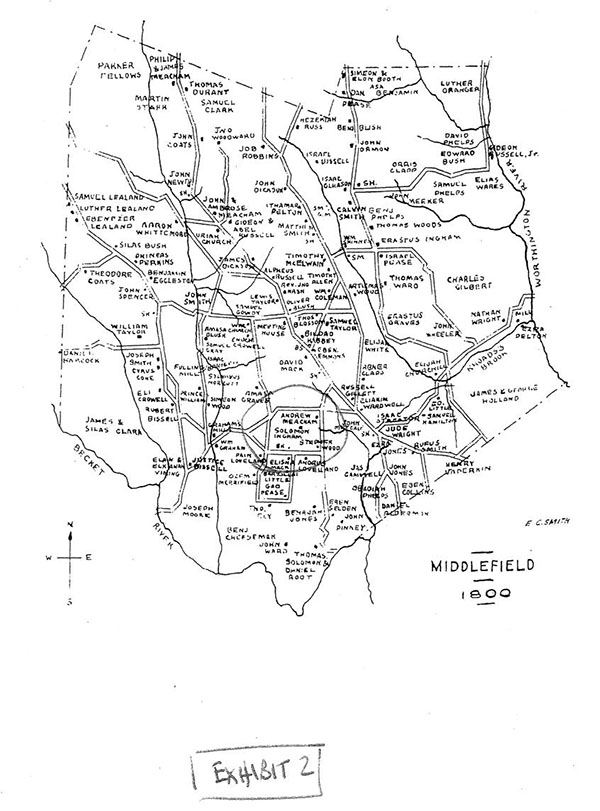

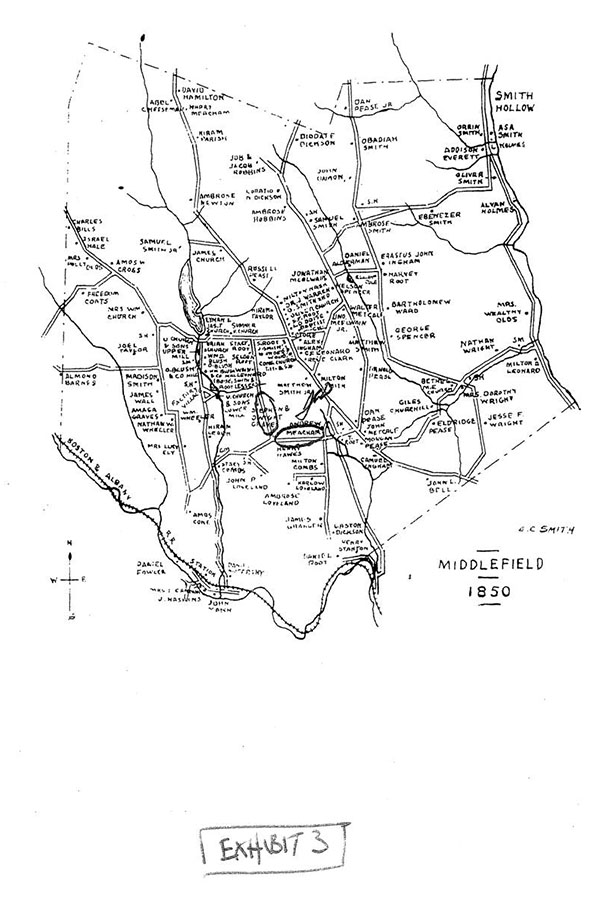

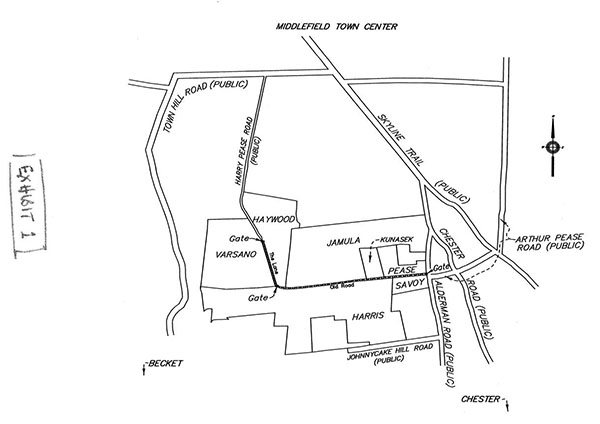

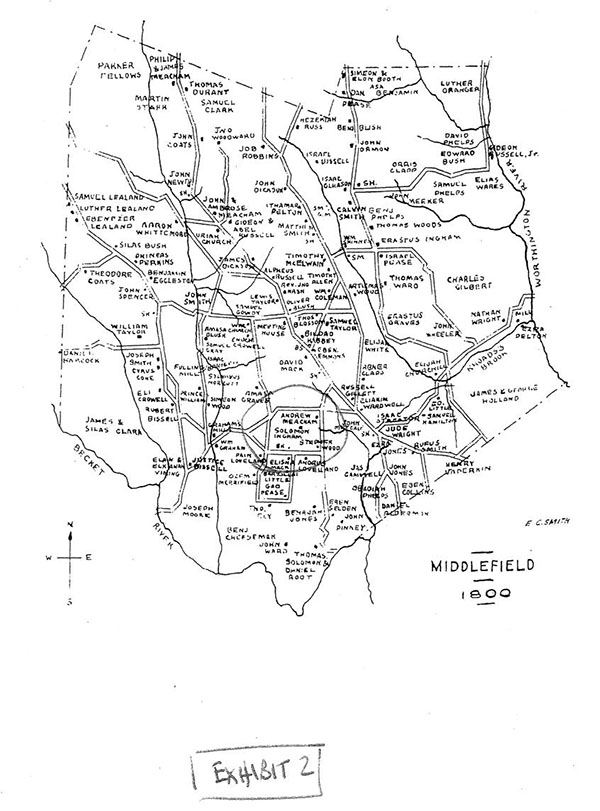

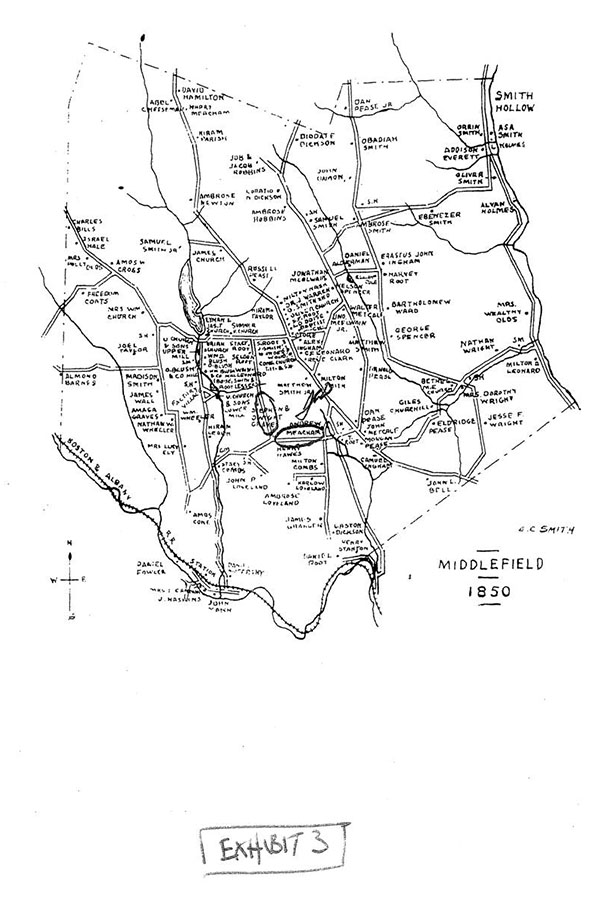

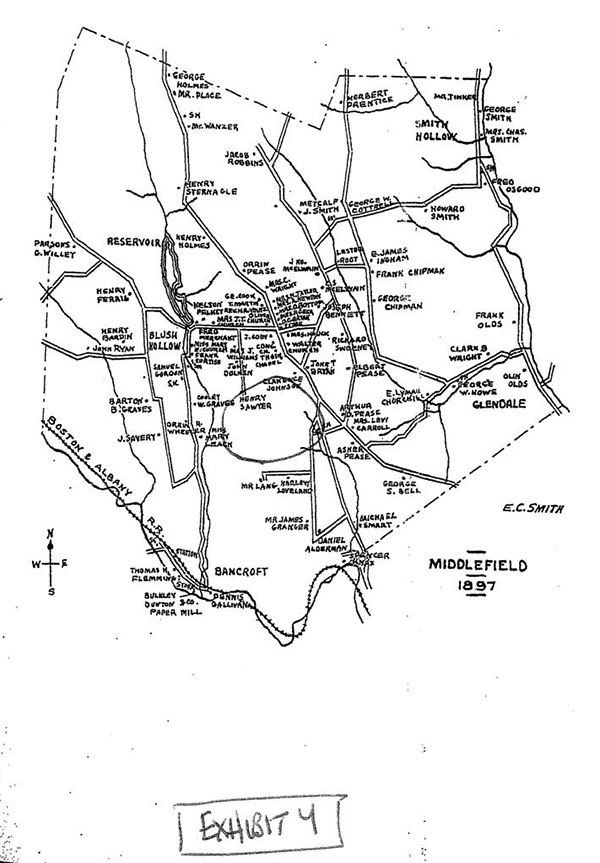

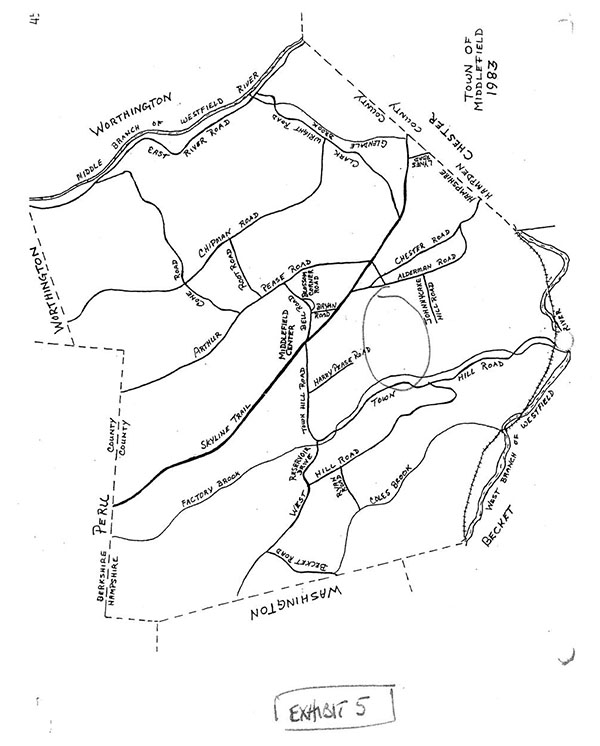

I attach five maps to assist the reader in following the narration in this Decision. The first (Ex. 1), as previously noted, is a sketch showing the locations of the parties' properties, the public roads that serve them, the Lane, and Old Road. The second (Ex. 2) is a map from 1800 with the relevant area circled. The third (Ex. 3) is a map from 1850. The fourth (Ex. 4) is a map from 1897, approximately ten years after the 1886 discontinuance (the roadways at issue are now gone). The fifth (Ex. 5) is the official town map from 1983, showing all of the public roads in the town (neither of these roadways is on the map). The significance of each of these maps is explained below.

To properly understand and analyze the issues in the case, it is important to remember that there are two former roadways in question - the Lane and Old Road. They are not, and have never been, a single roadway, either in origin or analytically. In making their arguments, the plaintiffs seek to merge the two to bolster their claim of access over the Lane. This is wrong. As explained more fully below, none of the plaintiffs' properties has any right, public or private, to use the Lane. Old Road, though, has a different analysis, in part. While there are no public rights to use it, and the Harrises have no private rights of use, the Jamulas have a private right to use its northern half (the half that is on the Kunasek and Pease properties) by virtue of a deed from Yolanda Romano, the then-common owner of the Jamula, Kunasek and Pease parcels, to the Jamulas' predecessor-in-title. The Jamulas have no right to use the part of Old Road that is on the Savoys' land (the southern half), which Ms. Romano never owned.

The Roadways' Origins

The Lane and Old Road originated independently of each other, in two separate town meeting votes.

The first, by the Becket subscribers, [Note 7] came in 1780 and established a road from Becket that went north/south in this section. The Lane was a part of that road.

The second, by the 1805 Middlefield town meeting, [Note 8] established another road to Becket that, in this area, went east/west. Old Road was a part of that road.

The two roads crossed each other at what is now the southern boundary of the Varsano and Haywood properties, with both roads continuing past that intersection at that time - the north/south road continuing further south; and the east/west road continuing further west, linking to Town Hill Road.

While there were various pre-existing trails in the area, neither of these roadways followed those trails in the sections at issue in this lawsuit. Rather, the town meeting votes and resulting layouts established them in entirely new locations. I base this finding on the following.

The 1780 vote (the one relevant to the Lane) makes no mention of any pre-existing roadways or trails in its description of the route it takes. It states quite clearly that the Becket subscribers "laid" the road themselves, and the reference points it uses as it describes the location of the road are quite specific with none of those references mentioning any pre-existing roadway or trail. Similarly, the 1805 Middlefield town meeting vote (the one relevant to Old Road) says that its roadway was "laid out" by the Selectmen, and states specifically that, in the part at issue in this lawsuit (Old Road), it was relocated from what had been there previously [Note 9]. This relocation is apparent from a comparison of the 1800 map (Ex. 2 - the roadways that existed before the 1805 vote) with the map from 1850 (Ex. 3). As Ex. 2 shows, the pre-1805 east/west roadway angled northwest after its intersection with the 1780 (north/south) road and before it went eastward. As Ex. 3 shows, the post-1805 relocation eliminated the northwest jog and, instead, went straight east from the intersection. [Note 10] It is also clear that this new location did not follow a pre-existing trail of any kind. Whatever trails had been in the area before the new roadway was laid out and constructed were to its south. [Note 11] The stone walls along the edges of Old Road, scattered remnants of which are still there, date from the time Old Road was public. [Note 12]

Both the 1780 and 1805 votes were easement takings, not a taking of the underlying fees in the roadways. I base this finding on the language of the votes (neither of which calls for any taking of land, only the laying out of the roadways), the absence of any record of public expenditure for land taking, and, most importantly, the town's confirmation in its filings in this lawsuit that it has no ownership interest in any of these roadbeds. [Note 13] Thus, the roadbeds remained in private ownership, subject to the public easement, but subject to the easement only as long as that easement existed. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 161.

Although the 1805 town meeting vote (the Old Road taking) describes the taking as three rods wide, the area actually taken when the road was laid out was only two rods. This was the actual distance between the stone walls erected on the sides of the roadbed. [Note 14] I thus find that the taking was two rods wide, and that it was understood as that wide by its abutters when they referred to it in their deeds.

Because the Lane and Old Road were in new locations, beginning as public roads, there were no pre-existing private rights to use them that would have re-attached after the discontinuance. The analysis of the private rights, if any, that presently exist for their use thus begins from the date of the discontinuance. See id., 423 Mass. at 161-163.

The Discontinuance of the Roads

The 1800, 1850, and 1897 maps (Exs. 2, 3 & 4) show the gradual abandonment of the roadways in this part of Middlefield, and the reasons for their abandonment are not hard to discern. The residents of this area were never numerous, and the houses few. The land was hilly and heavily forested. [Note 15] Factories replaced farms as the primary employment and the population shifted in consequence, concentrating in what is now the Middlefield town center to the north, along Factory Brook to the west, [Note 16] and on the main roads to the nearby towns of Pittsfield, Becket, and Chester (Becket Road, Town Hill Road, Skyline Trail, and Alderman/Chester Road). Previously inhabited homesites in this area and to its south (the lands around Johnnycake Hill and Walnut Hill) were abandoned, and the former roadways that lead to those abandoned homes thus fell into disuse and were abandoned themselves. Compare Ex. 2 (1800 map), with Ex. 3 (1850), and Ex. 4 (1897). By 1850 at the latest, the north/south road (of which the Lane was then a part) ceased going south of the east/west road (of which Old Road was then a part) (see Ex. 3) and, not long thereafter, the east/west road no longer had any connection west to Town Hill Road - making it, in effect, a road to nowhere. It is thus no surprise that the 1886 town meeting voted to discontinue the north/south road south of its last remaining dwelling (the thenHenry Sawyer house, see Ex. 4), dead-ending it there, [Note 17] and no surprise that the same vote discontinued the east/west road west of Alderman Road since it no longer had any dwellings on it [Note 18] and no longer went any place the public had any reason to go. [Note 19] The details of the 1886 vote, and why I find that it discontinued all public aspects of both of these roadways, are discussed more fully below.

The Use of the Lane After its Discontinuance in 1886

The Lane is currently owned by its abutting landowners, the Varsanos to its midpoint on the west, and the Haywoods to its midpoint on the east. See Ex. 1. Its immediately prior owners (the owners of both sides of the Lane until it was sold off one side at a time, first-the west- to theVarsanos in 1962, and then-the east-to the Haywoods in 2012) were successive generations of the Pease family, [Note 20] dating back to 1902. For as long as any of the witnesses could remember (memories that stretch back at least 50 years prior to the filing of this case), the Lane has been (1) gated off at its north at the point where Harry Pease Road dead-ends, (2) gated off at its south at the point where it formerly intersected with Old Road, (3) enclosed in its entirety by a fence, and (4) used only to graze cattle. [Note 21] Except for the one occasion when Mr. Jamula claims to have driven along part of the Lane in a four-wheel-drive truck, and the handful of occasions he claims to have walked it - all of which occurred after 1994 and are thus well short of the twenty years required for any kind of prescriptive claim [Note 22] - there was no evidence of any use of the Lane after the 1886 discontinuance other than by the owners and invitees of the Varsano and Haywood properties. [Note 23] As noted above, there would have been no reason for the public to use the Lane because it was gated off, in active use for cattle grazing, and now that it no longer intersected with Old Road, lead nowhere. I thus find that there was no public use of the Lane after 1886 and thus no public prescriptive rights to use it today. [Note 24]

With respect to any private prescriptive rights to use the Lane appurtenant to any of the plaintiffs' properties, I find that no such rights exist. As previously noted, prescriptive rights require actual, open, notorious, adverse and continuing use for twenty years or more prior to the filing of the lawsuit in 2013, [Note 25] and there was no evidence that the plaintiffs or their predecessors in title used the Lane in any manner from the time of its discontinuance (1886) until Mr. Jamula took his single drive and occasional walks after 1994. This is not surprising, since there would have been no occasion for them to use the Lane at all, much less regularly and continuously: (1) the Lane was fenced and gated off and in active use by its owners, (2) it lead nowhere that was not more conveniently reached by other, public roads, (3) neither the plaintiffs nor their predecessors in title ever owned any part of the Lane or any of the land that abuts it, see Ex. 1 (showing location of the parties' properties), (4) the parts of the plaintiffs' lands that were closest to the Lane - the parts along Old Road - were uninhabited forestland, and (5) until Mr. Jamula built a hunting shack on Old Road in the Spring of 1995, there were no structures on that part of his land (its only house, now ruins, had been on Alderman Road, far to the east) and, as for the Harrises, the only house on their property in the part abutting Old Road (the Hawes house) was no longer inhabited by 1886 and, of a certainty, not after 1897 at the latest [Note 26] (the house in which the Harrises live is in the same place where their predecessor-owners also lived - south of Old Road and directly on Johnnycake Hill Road). For all these reasons it is highly unlikely that anyone associated with the plaintiffs' properties made any use of the Lane after the 1886 discontinuance, [Note 27] and certainly not in regular, continuous fashion for twenty years or more. Mr. Varsano, who has watched the Lane for over fifty years, saw no such use. I find that there was none.

The Use of Old Road After Its Discontinuance in 1886

I turn now to the use of Old Road after its discontinuance in 1886. There were only two witnesses with direct personal knowledge of its use prior to April 1992 [Note 28] - Yolanda Romano and Timothy Pease - and their trial testimony was as follows. Ms. Romano, who had mobility issues, testified by deposition. Mr. Pease testified live.

Ms. Romano's knowledge arose as follows. On September 23, 1947, her family purchased all of the land abutting the north side of Old Road from the point of its intersection with Alderman Road west to the boundary of the now-Haywood (then-Pease family) [Note 29] property, approximately 150 acres in total, nearly all of which was vacant woodland. Their house was on the far eastern edge of that property, on Alderman Road, next to its intersection with the Old Road roadbed. Ms. Romano was a teenager when they moved there, and she either lived in or regularly visited that house from September 1947 until she went into assisted living around the time of trial. The Jamula land was part of the Romano property until Ms. Romano sold it to a predecessor of the Jamulas in 1974. The property now owned by Mr. Pease, and the property now owned by the Kunaseks, were both once part of the Romano land as well.

Defendant/witness Timothy Pease (as previously noted, no relation to the Peases who owned the now-Varsano and Haywood properties) is a long-time resident of the town (among other things, its former highway commissioner) whose observations of Old Road stretch back at least fifty years, nearly as long as Ms. Romano's. He purchased the property on the south side of Old Road now owned by his stepson Steven Savoy in 1985, and the land on the north side of Old Road which he still owns (formerly owned by the Romanos, with Ms. Romano retaining a life estate in the part occupied by her house) shortly thereafter.

Ms. Romano was a prickly but fully believable witness regarding the use of Old Road, and Mr. Pease was also a fully credible witness on such use. I credit their testimony in full. Their accounts were consistent with each other, and persuasive.

According to their testimony, Ms. Romano's father was a machine tender at a local mill who kept a small number of horses and cows in the area near their house, which was located on Alderman Road. Everything on the 150 acres beyond the pasture and outbuildings immediately surrounding their house remained forest, and there was no evidence that they ever harvested the trees. [Note 30] With the sole exception discussed below and the occasions when the Peases from the now Varsano and Haywood properties would come to visit the Romanos (i.e., as their invitees), the only use that was made of Old Road from the date Ms. Romano began living on it (1947) until the time the Jamulas first walked it in 1993 was as a grazing and pathway area for the Romanos' horses and cows and, on occasion, their tractor. [Note 31] There was no evidence that even this use extended as far west as the now-Jamula land (as previously noted, the horses and cows were stabled and pastured near the Romanos' house on Alderman Road), and there was no evidence that there was any use of Old Road before 1947 going back to the time of the discontinuance in 1886. This is not surprising. With its connection to the Lane now gated off and its former link to Town Hill Road long-since abandoned, Old Road was a dead-end that no longer lead anywhere. The landowners whose houses were on the Lane had other, easier access to the town center via the public Harry Pease Road at the northern boundary of their properties, and there was no one living on Old Road itself to give it any use. [Note 32] No one would have cut through because Old Road was gated off at its intersection with Alderman Road, blocking access from that direction. [Note 33] Its former roadbed had become rugged, narrow, overgrown by grass and trees, dirt and mud where the cows walked along it, and impassable when it rained or in the Springtime "mud" season due to its lack of drainage pitch. [Note 34] Both Ms. Romano and Mr. Pease stated, unequivocally, that except for the cows and the instance discussed below, they never saw any other use.

This sole exception was a single brief period of woodcutting in the late 1980s, whose circumstances, according to Mr. Pease, were these. Ms. Romano had sold a section of her land, now owned by Mr. Pease, to Michael Nevers, and Mr. Nevers was cutting wood to sell to a lumber mill in Chester. He had been removing it by horseback but, with winter coming on, asked Mr. Pease (a heavy-equipment operator) to assist him with a tractor. Mr. Pease bulldozed parts of Mr. Nevers' section of Old Road just enough to make them temporarily passable for the lumber mill's trucks, and he also bulldozed a landing and enough of a trail to get his tractor to the log assembly sites on the land being logged. [Note 35] The logging was apparently small-scale and time-limited. It also may have included land in addition to Mr. Nevers'. I say this because at least some of the log landings on Old Road bulldozed by Mr. Pease were actually on the Kunasek and then-Stern, now Jamula properties, and some of the logs that were cut by Mr. Nevers may thus have come from those properties as well - either a trespass (all of the land was heavily forested; Mr. Nevers may never accurately have located the boundaries and thus have cut on the neighboring land by mistake), or by permission. Mr. Pease did not know which it was (trespass or permission), Mr. Jamula did not know which it was (it occurred many years before he bought his land), Mr. Kunasek was not called to testify so his explanation is unknown, and no records of this logging were introduced into evidence at trial (none may, in fact, exist). In any event, the logging was done by Mr. Nevers and thus was not appurtenant to the Jamula land (which he never owned), and whatever use was made of Old Road outside of Mr. Nevers' own section was too limited in time and scope for prescriptive rights to arise. Judging by the degree of overgrowth described by the plaintiffs' forestry consultant, Mr. Collins, the logging that created the other woodland trails and roadways on the Jamula property likely dated from the time the roadway was public. There was certainly no evidence of any logging on it when it was owned by the Romanos, or at any time subsequent to their ownership up until the Nevers cutting.

The plaintiffs' forester, Mr. Collins, observed signs of this logging when he first came to the plaintiffs' properties in 2000. He also saw evidence of previous, very small scale tree work on the now-Harris property [Note 36] which he attempted to match up to the forestry plans filed with the state by the Harrises' immediate predecessor, John Marshall. Mr. Collins believed that the Marshall logging, in part, used Old Road to remove the logs, but I am not persuaded that this is so. Ms. Romano, who lived at its intersection with Alderman Road, did not recall any such use. There were logging trails on the Marshall (now Harris) land that lead back to Johnnycake Hill Road. [Note 37] None of the Marshall forestry or cutting plans indicated any use of Old Road for log removal (the 1977 Forest Management Plan showed access from Johnnycake Hill Road and a new "fire lane" to be cut along Old Walnut Hill Road on the western border of the Harris land, leading south). [Note 38] The 1983 Plan showed internal trails to, and access from, Old Walnut Hill Road and Johnnycake Hill Road (labelled "Berkshire Road" on that plan). [Note 39] So did the 1995 Plan. [Note 40] Old Road was gated off at that time and, as the Marshall Plans themselves indicated, was "abandoned." Mr. Pease's testimony about the late-1980s logging by Mr. Nevers established that at least some bulldozing on Old Road was necessary at that time for log trucks to use it, and there was no evidence that any bulldozing had occurred prior to that time. [Note 41] Moreover, if there was any use of Old Road by Mr. Marshall, it had to be permissive. Old Road was gated off. The lock on the gate was put there by Mr. Pease. [Note 42] The key Mr. Harris discovered in the Marshall's old house when he bought it was for the Pease lock, and thus could only have come from Mr. Pease. Finally, any Marshall use of Old Road for logging purposes (he had no need to use it otherwise - his house was on Johnnycake Hill Road) could only have been small scale and only, at most, on three brief occasions over an 18 year period (if Old Road was, in fact, used in connection with the 1977, 1983 and 1995 Plans). Otherwise, Mr. Pease and Ms. Romano would have remembered it.

Mr. Jamula testified that the first time he walked or drove along Old Road in the sections at issue in this lawsuit was in 1994. [Note 43] He and his guests subsequently drove along them on weekends after he built his hunting shack, but this was post-1994 (the hunting shack was built in the Spring of 1995). Mr. Harris testified that the first time he walked along any part of Old Road was after his October 29, 1994 purchase of his land, and the first time he drove along any portion of it was months later when he began visiting the Jamulas at their hunting shack (i.e., after the Spring of 1995 when the shack was built). The Harrises' one-time use of Old Road to remove logs from their property took place in the Fall of 2000 and, in any event, was done with permission. [Note 44] The Jamulas' use of Old Road to remove logs from their property did not begin until 2001, and again was limited.

In sum, I find that neither the Jamula property nor the Harris property used Old Road at any time after its 1886 discontinuance up until 1994. Since there was no such use prior to April 23, 1992, no private prescriptive rights exist in Old Road for either property. [Note 45]

There is No Public Right to Use Either the Lane or Old Road

The plaintiffs contend that, despite the 1886 town meeting vote and the subsequent town meeting votes in 1984 and 2012 discussed below, both the Lane and the Old Road, which began public, remain public. I disagree. I find and rule that their status as public roads was discontinued by the 1886 vote, and that all public rights of access ceased at that time. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 162-163. Although the 1886 vote used the words "shut up the road" [Note 46] rather than "discontinue", the two are equivalent and had the same effect - to end the roads' public status, fully and completely. I say this for the following reasons.

First, the 2012 Middlefield Town Meeting explicitly said that the intent of the 1886 vote was to discontinue these roads as public ways. [Note 47] That interpretation of the vote, by the same body that made it (town meeting), is a reasonable one and thus entitled to deference. See

Wendy's Old-Fashioned Hamburgers of New York, Inc. v. Board of Appeals of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381 (2009) (deference due municipal interpretation where it possesses special knowledge of history and purpose of enactment and interpretation is reasonable one).

Second, even if I give the Town no deference and interpret the 1886 vote entirely independently, "shut up the road", construed in context, plainly means to discontinue their status as public roads, and I so interpret it. Words and phrases in legislative enactments are construed in a "common sense" manner according to the common and approved usage of the language so long as those meanings are consistent with the statutory purpose. See G.L. c. 4, §6 (third rule) ("common and approved usage of the language"); Commonwealth v. Paquette, 475 Mass. 793 , 800 (2016) (same, using dictionary definitions as indicative of "common and approved" usage); Retirement Bd of Somerville v. Buonomo, 467 Mass. 662 , 668 (2014) (statutes to be interpreted "consonant with sound reason and common sense"). The dictionary defines "shut" as "[to] close", "stop", or "cease", and defines "discontinue" as "[to] stop doing, providing, or making." See Oxford Concise Dictionary (10th Ed., 1999) at 1330 ("shut") & 408 ("discontinue"). "Shut" and "discontinue" are thus equivalent in this context, and the 1886 meeting's use of the stark phrase "shut up" makes its intent to end the public status of the roads plain and unmistakable. It was plainly intended to close, stop, or cease the roads' public status entirely and not, as the plaintiffs contend, merely cease their public maintenance. [Note 48]

Third, the intent to discontinue the public status of these roads rather than simply cease their public maintenance while continuing a public right of access over them, is plain from the mode of enactment. A legal discontinuance of a road as a public way is done by formal town vote, which is what occurred here. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 161 n. 7. By contrast, a discontinuance of maintenance, which relieves a municipality of liability for care and maintenance of the road and does not extinguish the right of the public and abutting landowners to travel over it, is done by action of "the board or officers of a city or town having charge of a public way" after giving due notice, holding a public hearing, and making the requisite findings. G. L. c. 82, §32A (emphasis added); Nylander, 423 Mass. at 161 n. 7. That is not what occurred in 1886. Moreover, as noted above, the words "shut up the road" are as definitive as words can be. The public status of the roads was at an end ("shut up"). "Shut up" - stark, direct words - cannot reasonably be interpreted as merely meaning the town would no longer maintain the roads.

The plaintiffs nonetheless contend that a public right of access continued after the 1886 town meeting votes, and even after the votes in 1984 [Note 49] and 2012, [Note 50] because (they argue) the road was "a statutory private right of way" with public right of access. The answer to that contention is simple. There is no such thing as a private right of way with public right of access except in two situations, neither applicable here. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 162 (rejecting theories of "abutter's easement" and "public access private way" as "contrary to settled Massachusetts law").

The first is where a road was public, and only the public liability for its care and maintenance of was discontinued. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 161 n. 7. In that case, a public access private way is created. See id. But as noted above, that is not what happened here. The 1886 town meeting vote discontinued the roads as public roads, fully and completely, not just the maintenance obligation.

The second is where, on a now discontinued public road or a road that has always been private, a public way by adverse use arises. The creation of such a public way by adverse use "depends on a showing of actual public use, general, uninterrupted, [and] continued for the prescriptive period." Fenn, 7 Mass. App. Ct. at 84 (internal citations and quotations omitted). All of the elements necessary for a prescriptive easement must be proved, i.e. "the (1) continuous and uninterrupted, (2) open and notorious, and (3) adverse use of another's land (4) for a period of not less than twenty years." White, 464 Mass. at 413. See also Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 43-44. And, in addition, there is also a further fact that must be proved or admitted; "that the general public used the way as a public right; and that [the public] did [so] must be proved by facts which distinguish[] the use relied on from a rightful use by those who have permissive right to travel over the private way." Fenn, 7 Mass. App. Ct. at 84 (internal citations and quotations omitted; emphasis added). The burden of proving each and every one of these elements is on the claimant. See Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. "If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. at 453. Here there was no evidence, and certainly no persuasive evidence, of actual use by the general public, continuous and uninterrupted for twenty years, after the roadways' public status ended in 1886. Indeed, the evidence was directly contrary. The fact that they were discontinued as public roads by town meeting vote is strong evidence, in and of itself, that they were no longer in general public use. Moreover, the vote was accompanied by physical change. The sole part of the former roadways that remained public - the still public part of Harry Pease Road - became a dead end with a gate at its end, stopping well short of its former intersection with the Old Road. The area beyond that gate became a fenced-in pasture used only by its underlying landowners. The former Old Road itself no longer had any kind of traveled way west of its former intersection with the Lane, and there was nothing beyond that point to travel to. [Note 51] Moreover, as previously noted, Old Road too had been gated off (the steel cable across its intersection with Alderman Road), had deteriorated into a cowpath, was being used only by the Romanos and their invitees, and even then only in a short stretch near Alderman Road (the area leading to the outbuildings behind their house).

The plaintiffs' other contentions fail as well. As noted above, there is no "public access private way" in Massachusetts, nor any "abutter's easement" over former public ways. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 162-163. If the discontinuance of a public way cuts off a property's access to a public road (not the case here), the sole remedy is in damages against the municipality that discontinued the road. See id. at 163 n. 10. The plaintiffs' argument that the roads were not properly "taken" in 1780/1805 and thus have some other type of "public access" status is directly contrary to the evidence (the votes themselves) and without evidentiary support. Both roads were laid out and established as town roads by those votes, and there is a presumption that "such proper proceedings were had as will sustain [those] vote[s], unless [a party] shows some defect which renders [them] invalid." Geer v. Fleming, 110 Mass. 39 , 41 (1872). See also Gilmore v. Holt, 4 Pickering [21 Mass.] 257, 260 (1826) (presumption of legality for matters related to town meetings). The plaintiffs have shown no such defect. The evidence they offered of the current absence of expenditure records is insufficient to do so. It does not mean that no such expenditures were ever incurred, only that such records (from two centuries ago) have not been retained. Even if they had been retained for at least some period of time, they may well have been destroyed in the town hall fire in 1900 since, unlike records of town meeting votes themselves, they likely were not considered important enough to keep in the limited space available in the town's fire-proof safe. In any event, whatever "public" status these roads had was ended by the discontinuance vote in 1886.

There Is No Easement By Necessity Over the Defendants' Properties. Nor An Easement Implied from Pre-Existing Use. Benefiting Any of the Plaintiffs' Land

An easement by necessity may arise when a common owner of land conveys a landlocked portion of it - i.e. a portion without an express right of access to a road - and the portion so conveyed remains landlocked. In such situations, the law implies an easement across the grantor's retained land to give such access. Here, however, there is no such easement over either Old Road or the Lane, even if the plaintiffs' parcels previously used those roadways, because the plaintiffs' land is not presently landlocked. See Burlingame v. Gay, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 1135 , 2013 WL 2450580 at *2 (2013) and cases cited therein.

Both the Jamula and the Harris parcels abut public roads. Indeed, as admitted by the plaintiffs' consulting forester, Robert Collins, there are old woodland roads on the plaintiffs' properties that lead across them to those public roads. The access they provide may not be as easy, as useful, or as convenient as access over the defendants' land using Old Road or the Lane. [Note 52] They may require the use of different logging equipment or the expense of improving those roads to make them more useful and convenient. But that does not matter. So long as access is possible, however more expensive and less convenient it may be, no easement by necessity arises over another's formerly commonly-owned land. See Burlingame, 2013 WL 2450580 at 2.

Express Or Implied Rights Arising From The Plaintiffs' Deeds

I turn now to the question of whether the plaintiffs, or either of them, have express or implied rights to use the Lane or Old Road arising from the granting language in their or their relevant predecessors' deeds and, if so, where those rights exist. The plaintiffs have the burden of proof. See Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 757 (1945),

The Lane (no express or implied rights in either of the plaintiffs)

Neither the Jamulas nor the Harrises have any express or implied rights to use the Lane. None of their predecessors-in-title ever owned any part of it or was deeded any right to use it that they could have conveyed. Thus, regardless of whether the Jamula or Harris deeds purport to contain a right to use the Lane (they don't), any such language is ineffective. You cannot convey what you do not have. See Bongaards v. Millen, 440 Mass. 10 , 15 (2003).

Express Easements in Old Road (an express right in Jamula only, and only in the Northern half of Old Road)

The Jamula property has an express easement over the part of the Old Road roadbed that is on the Pease and Kunasek properties, i.e. its northern half, one rod wide. [Note 53] This is because all three of those parcels were in the common ownership of Yolanda Romano on April 25, 1974 when she deeded the now-Jamula property (the far western part of her land) to Mr. Jamula's predecessor John Egee, Jr., ''together with any rights of the Grantor herein to the way known as Johnney Cake Hill Road [Note 54] to be used in common with the Grantor herein and her heirs and assigns." This deed language was clearly intended to grant Mr. Egee an express easement over the portion of "Johnney Cake Hill Road" (Old Road) whose fee Ms. Romano retained - the northern half of the roadway, one rod wide, in the section from the now-Egee property on the west to Alderman Road on the east. [Note 55] This right was then transferred to each successor owner of the Egee land (now Mr. Jamula), either by express language in those deeds or operation of G.L. c. 183, §15. [Note 56] She had no rights, fee or easement, in the southern half of the roadbed now owned by Mr. Savoy, and thus could not convey any rights, of any kind, for the use of that land.

None of the deeds in the Harris' chain of title contain an express easement to use any part of Old Road, nor do any of the deeds in Mr. Jamula's chain of title contain an express easement to use its southern half. The plaintiffs thus argue that the language and history of the relevant deeds to their predecessors imply such a present-day easement. This is not the case.

Implied Easements in Old Road (none for any of the plaintiffs)

"The origin of an implied easement, 'whether by grant or by reservation...must be found in a presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable.'" Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 344 (1967), quoting Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. 102 , 103 (1940). Here, the relevant circumstances to be examined in discerning the deed grantors' intentions are the 1886 discontinuance of Old Road, why it was discontinued, and its lack of use and physical condition thereafter. None of these indicate an intention to grant an easement over Old Road. Indeed, they indicate the opposite.

As previously discussed, there were no private easement rights in Old Road pre-dating the creation of the public roadway. This was because there was no prior roadway in the location at issue, and thus no private easement rights to "re-attach." See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 161-163. Accordingly, private easement rights, if any, had to be created post-discontinuance, and the "circumstances" that existed then and thereafter were the discontinuance itself, the prior abandonment of all structures and use that had been the underlying cause of the discontinuance, the "gating-off' of the roadbed, its subsequent overgrowth and deterioration as a result of its gating-off and lack of use, and the existence of alternative access to public roads for all the property that was conveyed. [Note 57] As noted above, the only ones who used Old Road were the Romanos (for their cows), and it is instructive that they used explicit language when they granted an express easement to others for such use in the sections they owned in fee. The fact that no one else included such a clearly-stated express easement in their deeds is further evidence that no easement over Old Road, express or implied, was intended in those conveyances. [Note 58]

The plaintiffs' arguments against this are misconceived. They are based on the fact that, because certain bounding descriptions referenced Old Road and, at one time or another, a grantor in the chain owned land on both sides of Old Road, there must have been an intention to grant an easement over it. [Note 59] Not so. There is no "abutter's easement" over a former public road, so the fact that a public road existed prior to 1886, and plaintiffs' properties abutted it, grants them no easement rights. See Nylander, 423 Mass. at 162. The plaintiffs cite to case law holding that when a grantor conveys land bounded on a street or way, he and those claiming under him are estopped from denying the existence of such street or way. See, e.g., Murphy v. Mart Realty of Brockton Inc., 348 Mass. 675 , 677-678 (1965). But those cases are inapplicable because they require that such a way actually exist or, at least, be contemplated. Simply put, here there was no way, either actual or contemplated in the future. There had been a public way, but it had ceased to exist, its roadbed had been re-integrated into its respective owners' lands, and there was no contemplation to make it a private way. It had never been a private way, either actual or contemplated. It had been discontinued by the town, "shut up", gated-off, its roadbed rapidly deteriorated, and there was no credible evidence that it was used thereafter except, as discussed above, by the Romanos. Because Old Road no longer existed and had never existed as a private way, the grantors cannot be said to have intended to grant an easement to use it absent express language in their deeds to the contrary, and then only in the parts they then-owned. There is no such language in any of those deeds except for the Romanos' deed to Mr. Jamula's predecessor,

Mr. Egee and that, as previously noted, only granted an easement to the Jamula property, and only to the 1-rod wide northern half of Old Road that was on the remaining Romano (now Kunasek and Pease) property.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that both the Lane and Old Road were discontinued as public roads by the 1886 town meeting vote. I find and rule that none of the plaintiffs have any rights, on any basis, to use any part of the Lane. I find and rule that the Jamula plaintiffs have an express easement to use the northern half of Old Road, one-rod wide, in the sections that cross the Kunasek and Pease properties, but that is the only easement right they have. They have no right to cross any of the land on its southern half owned by the Savoys. The Harris plaintiffs have no easement rights to any part of Old Road.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

exhibit 3

exhibit 4

exhibit 5

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] See testimony of the plaintiffs' forestry consultant, Robert Collins.

[Note 2] See discussion below.

[Note 3] See Article 18, Results of the Middlefield Annual Town Meeting at 7 (May 5, 2012), recorded in the Hampshire Registry of Deeds at Book 11196, Page 177 (Jan. 23, 2013), which expressly directed the tax assessor to remove the words "Harry Pease Road" from its maps for any portion of the roadways in dispute in this case, declaring that that label, for anything other than the public Harry Pease Road that dead-ends north of this area, was erroneous. See also Waters v. Cook, 13 LCR 553 , 2005 WL 2864806 at *7 (Mass. Land Ct., Nov. 2, 2005) (tax assessor's maps have nothing to do with title, which is governed by deed instruments); Hubbard Health Systems Real Estate Inc. v. Finamore, 24 LCR 516 , 2016 WL 4418195 at *10 (Mass. Land Ct., Aug. 19, 2016) (same, citing Waters).

[Note 4] See discussion below.

[Note 5] The parties stipulated that all three town meeting votes (1886, 1984, and 2012) were about the two roadways in dispute in this case. See Docket Entry (Oct. 9, 2012). There is thus no issue regarding their applicability to the former roadways, only their proper interpretation.

[Note 6] I previously declared that neither of these roadways was currently a public road when I granted the town's motion for judgment on the pleadings, dismissing it from the case. Memorandum and Order on Defendant Town of Middlefield's Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings (Jan. 29, 2013). The plaintiffs' Second Amended Complaint (filed May 13, 2013) thus dropped the town as a defendant. What is still active, however, is the plaintiffs' request for a declaration of when that public status ceased.

[Note 7] This area of Middlefield was part of Becket at that time. The subscribers were its town meeting members.

[Note 8] Middlefield became a separate town on March 12, 1783.

[Note 9] See the record of the 1805 town meeting, which describes the layout of the road (three rods wide, running between the Meacham and Macks lots, with half its width on Meacham's land and the other half on Mack's), and states, ''the above said Road was Established at a town Meeting Holden April 1st 1805 and voted at the Same Meeting to discontinue the Part of Road Formerly laid on said Meacham land which The Part of the Road laid on Capt Elisha Macks Land [makes] surplus."

[Note 10] As the maps show, the location of the connecting road to the east was also changed accordingly, now angling down to meet the 1805 roadway rather than, as previously, going straight west to meet the former location of the east/west road.

[Note 11] See Edward Church Smith and Philip Mack Smith, A History of the Town of Middlefield, Massachusetts (1924) at 3 ("The Pioneers and Their Trails"). The pre-existing trails so referenced were described as leading to various home sites, which the maps show were south of this new roadway. See the 1800 map attached hereto as Ex. 2 for the locations of these houses.

[Note 12] See testimony of plaintiffs' expert, James Smith.

[Note 13] See Defendant Town ofMiddlefield's Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings at 7 (Aug. 22, 2012) ("The town does not claim any ownership interest in the way.").

[Note 14] See testimony of the plaintiffs' expert James Smith, who testified that the walls were likely put there "about the time or soon after the time the roadway became public" and that the walls "were roughly 33 feet apart, two rods." Trial transcript, Vol. 1 at 48 - 51. His testimony regarding wider widths was about other roadways he had seen over the course of his career that had special terrain or drainage issues, none of which existed here. As he stated, "most road layouts are only two rods wide." Id at 51.

[Note 15] Much of it is now state forest or wildlife management area.

[Note 16] Town Hill Road runs alongside Factory Brook.

[Note 17] The remaining part of the road ended at the gate at the top of the Lane. This remaining part was subsequently named Harry Pease Road after a member of the Pease family that owned the land to which it lead (the land at the end of the dead-end, now the Varsano and Haywood properties).

[Note 18] The Henry Hawes (later E & M Smith) house on Old Road (located on the now-Harris property), shown as existing in 1850 (see Ex. 3), was no longer inhabited in 1897 (see Ex. 4, where it is no longer shown). All that remains of that house today are the ruins of its foundation and well. Based on the state of the ruins, the 1886 discontinuance of Old Road, and the absence of any contemporary claim related to that discontinuance, I infer, and so find, that the Hawes house had been abandoned prior to the discontinuance.

[Note 19] See Ex. 4 (1897 map), where neither the north/south nor the east/west roadway any longer appear; and Ex. 5 (1983 official map of all public roads in Middlefield) (same).

[Note 20] No relation to defendant Timothy Pease.

[Note 21] See testimony of defendant Leo Varsano, who (together with his wife Carol) purchased the western part of the land from the Pease family in 1962 and has direct, personal knowledge of the Lane from that time forward. According to Mr. Varsano, the Peases used its enclosed area for cattle grazing, and had done so "for generations." As he testified, the Lane was gated off at both ends at the time of his purchase, and remains so. He has not seen any traffic on the Lane, at all, at any time. I find that, if there was such traffic, he would have been aware of it. That he saw none means there was none. There was no evidence to the contrary, and certainly none I find credible.

[Note 22] As discussed in the analysis section below, prescriptive easements require adverse use that has been actual, open, notorious, continuous, and uninterrupted for twenty years or more prior to the filing of the lawsuit putting it at issue. See 16 Shawmut Street LLC v. Piedmont Street, LLC, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 1132 , 2017 WL 3122418 at *2 & n. 6 (2017) and cases cited therein ("The filing of a complaint to establish title to land immediately interrupts adverse possession. See Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 , 542 n.8 (1996)."). This action was filed on April 23, 2012. Activities that began in 1994 thus fall well short of the twenty year period. Moreover, Mr. Jamula's activities on the Lane - a single instance of driving and a handful of walks - are insufficiently open, notorious, continuous and uninterrupted to satisfy the other criteria for a prescriptive easement even had they begun prior to April 23, 1992, which they did not.

[Note 23] Mr. Harris, for example, does not claim to have ever walked or driven on any part of the Lane, nor to have ever seen anyone doing so. So far as his testimony shows, he only ever went as far as the fence that gated off its southern end.

[Note 24] As previously noted, for a private prescriptive easement to exist, the claimant must prove "the (1) continuous and uninterrupted, (2) open and notorious, and (3) adverse use of another's land (4) for a period of not less than twenty years." White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 413 (2013). See also Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007). For public prescriptive easements, there is also a further fact that must be proved or admitted; ''that the general public used the way as a public right; and that [the public] did [so] must be proved by facts which distinguish[] the use relied on from a rightful use by those who have permissive right to travel over the private way." Fenn v. Town of Middleborough, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 80 , 84 (1979) (internal citations and quotations omitted; emphasis added). There was no such proof in this case.

[Note 25] Seen. 22.

[Note 26] See n. 18.

[Note 27] The Harris house was, and is, on Johnnycake Hill Road. Thus, the route its inhabitants would have taken to the Middlefield town center would have been via Alderman Road. See Ex. 1. The only house that was ever built on the Jamula property was directly on Alderman Road (its ruins are still there). Thus, its inhabitants also would have used Alderman Road to get to the town center. See id. Neither had any apparent incentive to use the Lane, which would have taken them far out of their way.

[Note 28] Recall that, to count towards prescriptive rights, the initial open, notorious, adverse, and non-permissive use must have begun, at the latest, on or before April 23, 1992 (i.e., twenty years or more prior to the date the lawsuit was filed) and continued thereafter, uninterrupted, for at least twenty years. See n. 22.

[Note 29] No relation to defendant Timothy Pease.

[Note 30] The way through the woods on the northern part of the now-Jamula land, leading from roughly the triangle intersection of Chester and Alderman Roads due west, apparently pre-dates the Romanos. This woodland way appears to be the route taken by Mr. Jamula in 1993 when he first looked at the property he now owns.

[Note 31] Timothy Pease corroborated this. He too saw no one using it prior to 1993 other than the Romanos and their invitees, except for the single instance described below. To be appurtenant to the Jamula or Harris properties, a use must have been made either by or on behalf of the then-owner of that property. See Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 ,454 (1949); Holmes v. Turner's Falls Co., 150 Mass. 535 , 547 (1890) (tacking).

[Note 32] As previously noted, the only inhabited structure that had ever been on Old Road prior to 1994 was the Hawes house, and that had been uninhabited since before the 1886 discontinuance. See n. 18.

[Note 33] Mr. Pease testified that it had a steel cable stretched across it from the time he first saw it, which remained there until he replaced the cable with his own fence in 1986. He added a second fence, further down the former roadbed, in 2006.

[Note 34] The various pictures of Old Road that were introduced into evidence are pictures of its present state, and are not indicative of what was there before. The improvements they show (gravel and grading in some sections) are relatively recent. Mr. Pease did minor grading as described below. Mr. Savoy graded and improved the front section (the part from the intersection with Alderman Road as far as his newly-built home, on the part of the old roadway owned by him and, by permission, the part owned by his stepfather, Timothy Pease) for use as his driveway. Mr. Jamula began to do grading and graveling after 1994, but stopped when challenged by Mr. Pease. Any minor graveling done by Mr. Harris' forester on the occasion he removed logs using Old Road was after 2000, and, like the log removal using the road itself, was done with Mr. Pease's permission.

[Note 35] Mr. Pease testified that the small log landing on the other side of the Old Road roadbed, on land now owned by the Harrises, was put there by Mr. Nevers in connection with these same woodcutting activities.

[Note 36] The Harrises bought it in 1997.

[Note 37] See Trial Ex. 56 (attached plans).

[Note 38] See Trial Ex. 56 (attached plans). Mr. Collins testified that he thought this reference was actually to Old Road, but I find otherwise. The various plans show Old Walnut Hill Road in an entirely different location, abutting the now-Harris property on its west and then leading south.

[Note 39] See Trial Ex. 58 (attached plans).

[Note 40] See Trial Ex. 59 (attached plans).

[Note 41] The next bulldozing did not occur until 1986, when Mr. Pease bulldozed it from the intersection with Alderman Road to the site of the now-Savoy house so that that house could be built (Mr. Savoy is Mr. Pease's stepson). Mr. Savoy subsequently made further improvements to that section, angling it so that water drained off and adding gravel so that he could use it as the driveway to his house.

[Note 42] No one else put a lock on it until 1995, and even then the position of Mr. Pease's lock was such that he could lock everyone else out from using Old Road whenever he so chose.

[Note 43] To go over it in more detail, the Jamulas did not buy their land until November 10, 1994. Michael Jamula (now deceased) testified that he first saw the property with a realtor in 1992, but they parked where it abutted Chester Road and did not go as far as Old Road. He did not go onto any part of Old Road until 1993, when he again parked where the property abutted Chester Road and then walked the perimeter of the land, presumably including the portion of that land that includes the Old Road roadbed west of the Pease, Savoy and Kunasek sections that are the subject of this lawsuit. According to his testimony, he did not go onto the Pease, Savoy and Kunasek sections until later in 1993 when he saw that the gate barring access to them was unlocked at that time. He did not go onto those sections on any kind of continuing basis until the Jamulas purchased their land in November 1994, and not on a regular basis until after the hunting shack was built in the Spring of 1995.

[Note 44] Seen. 34. Mr. Pease testified that he gave the Harrises' forester (Mr. Collins) permission to use the roadbed on this occasion, and Mr. Collins conceded that he telephoned Mr. Pease to inform him of the upcoming logging and received "implied permission" during that call to use the roadbed for that purpose.

[Note 45] See nn. 22 & 28.

[Note 46] The 1886 town meeting vote was as follows. "Article 10 from the Town Warrant of March 1, 1886. To see if the town will shut up the road commencing near the Meacham place so called and thence over Jonny Cake Hill, so called, to the road leading from Factory Village to the depot, then commencing at the Loveland place, so called, thence to the first mentioned road. Action Taken on Article 10. Voted to shut up the road named in the 10th Article of the warrant." The parties agree that this was intended to describe the roadways in question.

[Note 47] The 2012 town meeting vote was as follows. "This vote to discontinue ratifies the original approved town votes of 1886 and 1984 whose intents were this very same discontinuance." Town of Middlefield Results of the Annual Town Meeting, May 5, 2012 at 3. The 1984 vote was taken at town meeting to inventory all town roads and approve the town's official map showing them. A copy of that official map is attached as Ex. 5. These former roadways were explicitly and intentionally not on that inventory or map.

[Note 48] The plaintiffs argue that town meeting's use of the words "shut up" on some occasions, and "discontinue" on others, indicates differing intents. As the very document they cite to support this argument shows, however, they are incorrect. This document, part of the record of the 1984 town meeting (Trial Ex. 29), is a list entitled "Discontinued Roads in Middlefield" and contains the date and language of each vote. It is clear not only from the title of the list ("Discontinued Roads"), but also from reading through the entries themselves, that the words "shut up" and "discontinue" are used interchangeably to mean the same thing. This is most apparent in the record of the March 1, 1880 vote, Art. 12, ''to see if the Town will discontinue the road from the Chester Line near the West Woolen Co.'s Mill to the road near the house of Wm. Alderman", and the action taken on that article: "After considerable discussion voted to shut up the road named in the 12th Article." As previously noted, the 2012 town meeting regarding these roads expressly interpreted "discontinue" and "shut up" as equivalent, with both meaning a full discontinuance of the public status of the road.

[Note 49] As previously noted, the 1984 vote was taken to confirm which roads in the town were public. Both an inventory listing and a map were referenced and incorporated in the vote (Ex. 1 is that map). With the exception of the northern part of Harry Pease Road (the dead-end) which had always remained public, neither of the roads at issue in this lawsuit was on the list or the map.

[Note 50] The 2012 vote was taken as a result of the access controversy being litigated in this case, and was in two parts, as follows:

Article 17 [as amended at town meeting]. "To see if the Town will vote to discontinue the Old-West road running from Alderman Road to the site of the old grist mill on Factory brook. The road has been known as "The Becket Road", the Old road to the Mill", and "Meecham's Road" amongst others. The length of this abandoned road is about 1.19 miles; and also to discontinue the North-South road that runs from the first road to where the Legal Harry Pease Road ends at the locked gate. This side road to be discontinued has a length of about 0.18 miles. More exactly the first point on Alderman Road is at (approximate) decimal coordinates (42.333276-73.004869) and runs to (42.330330-73.017818). The second road runs from a point on the first (42.331884-73.019943) to the locked gate at (42.334287-73.021102), which is also the Southern dead end of Harry Pease Road. This vote to discontinue ratifies and affirms the original town votes of 1886 and 1984 whose intents were this very same discontinuance." [Passed by secret ballot, 90 ''yes", 17 "no"].

* * * * * * *

Article 18. "It was moved and seconded to see if the Town will vote to direct the Board of Assessors toremove the erroneous use of the name 'Harry Pease Road' from any place on the town Assessors' maps other than the accepted Town Road with its north end starting at Town Hill Road and running southward for a distance of .81 miles to a dead end, encompassing only a north to south orientation as shown on the 1983 map of town roads, which accompanied the list of accepted roads voted at the 1984 Town Meeting. Article 18 passed as presented."

Results of the annual town Meeting, May 5, 2012 at 2-3, 7.

[Note 51] See, e.g., the 1893, 1948 and 1973 U.S. Geological Survey/Mass. DPW Maps of the Becket Mass. Quadrangle (Becket, Middlefield and Otis), which depict the then-existing roadways and structures in that overall area as of those dates. They show no roads, and no indication of former roads, west of the former intersection, and no homes or other structures anywhere along the Lane or Old Road.

[Note 52] Mr. Collins testified that the woodland road on the Jamula property that leads to Alderman Road goes through a wet area and a habitat protected zone. He conceded, however, that it could be used for removing logs if smaller equipment was employed or, after the necessary permits were obtained, by any-sized equipment once the road was improved.

[Note 53] As previously mentioned, the 1805 town meeting vote laid out the Old Road roadway along the boundary line of the Meacham (on the north) and Macks (on the south) lots, half on each. The actual taking was two rods wide. I thus find that any reference in a deed to rights in that way was intended and understood as intended to refer to that two rod wide area.

[Note 54] The reference here to "Johnney Cake Hill Road" was intended to refer to Old Road. The road currently named Johnny Cake Hill Road (formerly known as Berkshire House Road) is to the south and is the public road on which the Harris property abuts and which provides public access to that property.

[Note 55] That this was intended as a grant of an express easement is apparent from her calling that part of the land she was retaining a "way", and her use of the words "to be used in common with the Grantor herein and her heirs and assigns" (emphasis added). By his deed from Ms. Romano, Mr. Egee thus received the fee in the area of the roadbed on the land he was granted (the far-Western part of the Romano property), and an easement over the roadbed sections on Ms. Romano's remaining land to its east - the land now owned by Mr. Pease and the Kunaseks - which lead to Alderman Road. Ms. Romano's subsequent grants of the land she retained to Mr. Pease and the Kunaseks were subject to Egee's (now Jamula's) express easement over it because she could only grant what she had, and she had already conveyed the easement to Mr. Egee. See Bongaards, 440 Mass. at 15.

[Note 56] "In a conveyance of real estate all rights, easements, privileges and appurtenances belonging to the granted estate shall be included in the conveyance, unless the contrary shall be stated in the deed, and it shall be unnecessary to enumerate or mention them either generally or specifically." G.L. c. 183, §15.

[Note 57] The plaintiffs' arguments based on prior ''trails" in other locations, or on no-longer existing houses to which these trails may have led in the past, or (for that matter) to any pre-1886 condition, are thus irrelevant. Simply put, these were not part of the circumstances that existed at the time of the post-discontinuance deeds. At that time and after, there was no roadway and the grantors of those deeds did not intend to grant easement rights to a roadbed that, effectively, no longer existed. To the contrary, they were simply granting the tracts of land described in the deeds, all of which had other access. I so find.

The plaintiffs' argument that the 1959 deed from Mr. Dyer to the Marshalls of tax assessor parcels 35, 36, and 36.1 must have intended an easement over Old Road because that land was otherwise landlocked is factually incorrect. Tax parcel 36.1, which was conveyed together as a merged property with parcels 35 and 36, fronts on Johnny Cake Hill Road, a public road, which provided legal access to all of that land.

[Note 58] See, e.g., the 1895 deed from Charles Coombs to Richard and Lizzie Sweeney (Book 477, Page 107-108, part of Trial Ex. 16) that references Old Road (described as "a discontinued highway leading from the School House to Bancroft") only as a bound and specifically notes that it was a discontinued highway. Trial Ex. 16, p. 17. The other highways listed (the "highway leading from Chester Village to Middlefield" [Chester Road]; "the highway leading from [Daniel] Alderman's house to Middlefield" [Alderman Road]; and "the highway leading to Alanson Fergerson's house") were all active public roads and provided full access to the property conveyed. Far from purporting to grant any private rights to use any of these roads, the deed is careful to note that they were all "reserv[ed] and except[ed]" from the conveyance.

All other deeds cited by the plaintiffs where the grantors owned land on both sides of Old Road are of land with similar access to public roads. No easement over Old Road was mentioned or intended in any of them because, after the 1886 discontinuance, Old Road was not an actual road.

[Note 59] No such claims are made, or could be made, with respect to the Lane because none of the plaintiffs' properties abut it.

ANTHONY JAMULA as personal representative of the Estate of Michael Jamula, STEPHEN HARRIS, and GITA JOZSEF (HARRIS) v. TOWN OF MIDDLEFIELD, JANINE SAVOY, STEVEN SAVOY JR., TIMOTHY PEASE, ANTHONY KUNASEK, LINDA KUNASEK, LEO VARSANO, CAROL VARSANO, GEORGE HAYWOOD and DENISE HAYWOOD.

ANTHONY JAMULA as personal representative of the Estate of Michael Jamula, STEPHEN HARRIS, and GITA JOZSEF (HARRIS) v. TOWN OF MIDDLEFIELD, JANINE SAVOY, STEVEN SAVOY JR., TIMOTHY PEASE, ANTHONY KUNASEK, LINDA KUNASEK, LEO VARSANO, CAROL VARSANO, GEORGE HAYWOOD and DENISE HAYWOOD.