JONATHAN MILLEN and HELEN MILLEN v. ANNE PARDEE, HARRY PARDEE III, and RUTH GEORGE.

JONATHAN MILLEN and HELEN MILLEN v. ANNE PARDEE, HARRY PARDEE III, and RUTH GEORGE.

REG 13-43479

October 10, 2018

Essex, ss.

LONG, J.

DECISION

Introduction

This is a registration case brought by plaintiffs Jonathan and Helen Millen concerning land in the Pigeon Cove area of Rockport. In it, they make three claims.

The first is their claim to an "L"-shaped parcel fronting on Landmark Lane (Lot 78 on the Tax Assessor's Map), which the Land Court Title Examiner determined they owned and whose ownership no one contests. [Note 1] This is where their home, purchased on December 3, 2004, is located, and is the land their deed describes. [Note 2]

The second is their claim to fee ownership of an additional 16.5'-wide strip of land abutting the "toe" of the "L" (Tax Assessor's Lot 12A). [Note 3] That strip is currently fenced off from the "L" by a 6'-high stockade fence put there by defendant Ruth George, is included in Ms. George's deed as part of her property, [Note 4] and is taxed to, claimed, and used by Ms. George as part of her residence subject to the easement rights of the Condominium property to its south. [Note 5]

Lastly, the Millens claim a 15'-wide easement across the length of defendants Anne and Harry Pardees' homesite, running from Granite Street to the eastern edge of their property at the corner of the upper part of the "L", and assert that whatever rights anyone may have to the section of that alleged easement that continues across their land, if there is such an easement and such a section, have either been abandoned or extinguished.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule as follows. I also strike all portions of Ms. Millen's Affidavit Regarding Title which she recorded at the Registry on December 23, 2011 (Book 30956, Page 428) that are inconsistent with my findings and rulings.

Facts and Analysis

These, and the facts already stated, are the facts as I find them after trial.

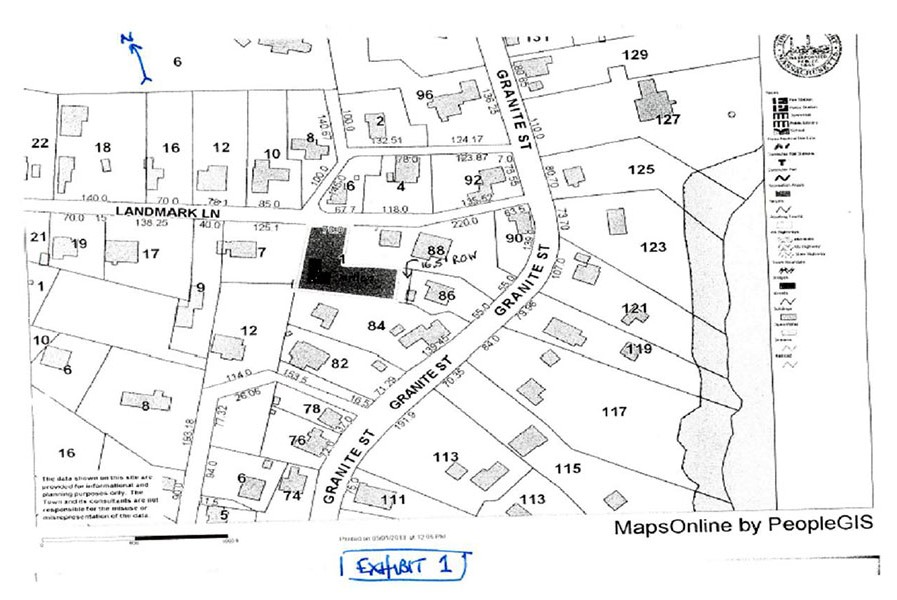

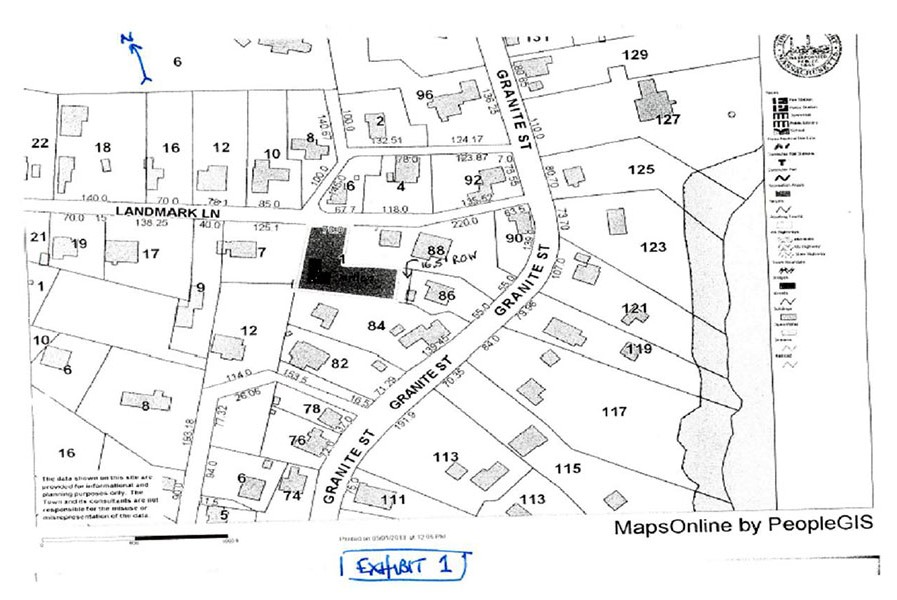

To show the relative locations of the parties' properties, a copy of the town's GIS map of the area is attached to this Decision as Ex. 1. The Millens are at 1 Landmark Lane, and the "L" is the dark-shaded parcel. The Pardees are at 88 Granite Street. Ms. George is at 86 Granite Street and the 16.5' Wide Right of Way area (the rear part of her property) is labelled "16.5' ROW." The Condominium is at 84 Granite Street.

The Millens Have Good Title to the "L"

Based on my review of the deed chain and the survey evidence submitted in connection with the registration petition, subject to an updated and complete review of the Millens' record title and matters not in issue during the trial, [Note 6] I find that the Millens have good title, suitable for registration, to the "L". This is the property whose boundaries are shown on their Petition Plan (43479-A), with the exception of the area labelled "16.5' Wide Right of Way" which, as set forth below, I find they do not own. Due notice was sent to the defendants, all other abutters, all other potential claimants identified after diligent search, and published generally. No one objected to the Millens' claim to the "L" or its boundaries as shown on their plan, and the defendants expressly assented. [Note 7]

As more fully set forth below, I further find that, subject to the above-referenced updated and complete review of the Millens' record title and matters not in issue during the trial, no one has easement rights over any part of the "L." No one asserted any during the course of these proceedings, and the defendants expressly stated that they had none.

The Millens Do Not Own Any Part of the 16.5' Wide Right of Way and Have No Easement Rights to Use it.

The Millens claim the fee in the 16.5' Wide Right of Way, but their deed does not describe any part of it as included in their property. To the contrary, the metes and bounds description in that deed gives measurements that stop at the line of the Right of Way and use that line as a monument, and the total square footage of their property as described in their deed does not include any part of the Right of Way. Current "on the ground" conditions are consistent with their lack of an ownership interest. There is a six-foot high stockade fence along the line of the Right of Way which blocks access to it from the "L", [Note 8] and Ms. George and her predecessors have long-since incorporated that area into her lawn. The Millens do not claim title by adverse possession to any part of the Right of Way, nor does the evidence support any such claim. [Note 9]

Instead, the Millens' claim to the fee in the Right of Way is based entirely on G.L. c. 183, §58, the "Derelict Fee Statute." The background to that claim is as follows.

All of the land relevant to this case the Millens' "L", the Pardee property, the George property (including the 16.5' Wide Right of Way), and the Condominium property -- was originally owned by Eliza Goodwin. In a series of deeds from 1923 to 1932, Ms. Goodwin [Note 10] conveyed the now-George property, with the exception of the 16.5' Right of Way, to Robert and Mathilda Anderson; [Note 11] the now-Millen and now-Pardee properties, along with the 16.5' Wide Right of Way, to Hulda Johnson and her husband; [Note 12] and retained the Condominium parcel (apparently where her house was located) for herself.

In connection with these conveyances, for the benefit of her remaining land (the Condominium parcel), Ms. Goodwin created and retained (1) an express easement over the 16.5' Wide Right of Way area, and (2) a 15'-wide easement on the now-Pardee parcel, [Note 13] running along the northern boundary of the Anderson (now-George property), from the 16.5' Wide Right of Way to Granite Street. See Trial Exs. 1-4. Lastly, Ms. Goodwin granted the Anderson property the right to use the 15' easement (Trial Ex. 3), and it is used today by the Pardees and Ms. George as their common driveway, as well as occasionally by the Condominium. The Millens' claim of a right to use the 15'-wide easement, and to extend it as far as their property line, is discussed below. For the reasons I explain there, I find that the Millens have no such right.

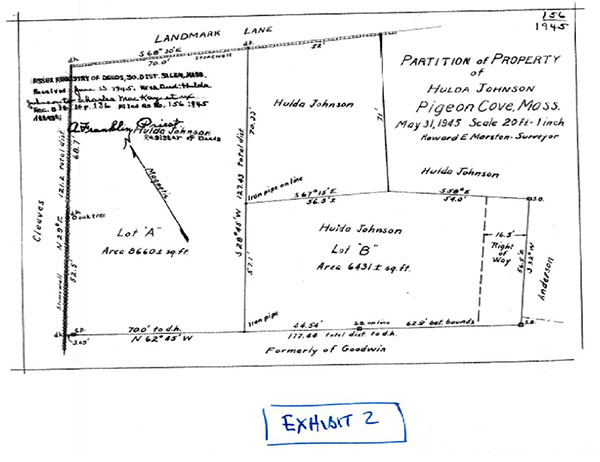

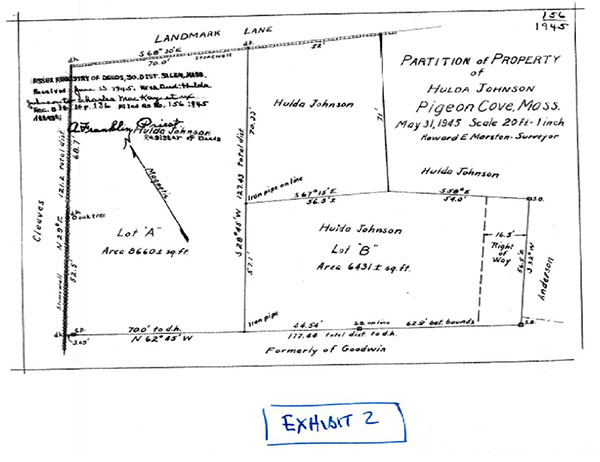

By plan dated May 31, 1945 and recorded June 13, a copy of which is attached hereto as Ex. 2 (the "Partition Plan"), Ms. Johnson partitioned her land into four distinct parcels Lot A (fronting on Landmark Lane), Lot B (landlocked at that time), a Lot without a letter to the north of Lot B and east of Lot A (fronting on Landmark Lane) (now the back part of the Pardee parcel), and a Lot without a letter to the east of that which fronted on Landmark Lane and Granite Street (now the front part of the Pardees' property). None of her subsequent conveyances of any of those Lots grant express easement rights to the 16.5' Wide Right of Way, and the reason is obvious. For those Lots, the 16.5' Right of Way led nowhere because Ms. Johnson had no right of passage over the Goodwin land to the south where that Right of Way led. When Ms. Goodwin created and retained that easement for her land (now the Condominium property), she did not grant any reciprocal easement rights over her land to Ms. Johnson.

Ms. Johnson conveyed her partitioned parcels as follows. None of these conveyances contained an express easement over any of her other land important, because any easements over that land created prior to her ownership were eliminated by merger, and would have had either to be expressly created again, or implied by necessity, to still exist. [Note 14]

Immediately after recording the Partition Plan, Ms. Johnson conveyed Lot A to Charles and Florence McKay (Jun. 13, 1945). A year later she also conveyed a portion of Lot B to the McKays (Jun. 28, 1946, recorded Jul. 23, 1946). [Note 15] Therefore that portion of Lot B merged with Lot A, was thus no longer landlocked (the combined Lots A and B fronted on Landmark Lane), and accordingly no longer had a claim to an easement by necessity, or any other "implied" easement, over any of Johnson's remaining land. See Hart v. Deering, 222 Mass. 407 , 410 (1916) ("where the necessity for such a way ceases, the right is at an end"); Viall v. Carpenter, 14 Gray [80 Mass.] 126, 127 (1859) (same). Lot A and that portion of Lot B are now the Millens' property (the "L"). As previously noted, the 16.5' Right of Way was ultimately conveyed by Ms. Johnson's successors to Ms. George's predecessors and became part of the George property. The other two parcels on the Partition Plan (the ones without a "letter" designation) ultimately became the Pardee property.

The Millens' Derelict Fee claim to the 16.5' Right of Way rests on the 1946 Johnson to McKay deed (Trial Ex. 7), which was explained and clarified in the 1948 confirmatory deed regarding that conveyance (Trial Ex. 10). The Derelict Fee statute provides:

Every instrument passing title to real estate abutting a way, whether public or private, watercourse, wall, fence or other similar linear monument, shall be construed to include any fee interest of the grantor in such way, watercourse or monument, unless (a) the grantor retains other real estate abutting such way, watercourse or monument, in which case, (i) if the retained real estate is on the same side, the division line between the land granted and the land retained shall be continued into such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or (ii) if the retained real estate is on the other side of such way, watercourse or monument between the division lines extended, the title conveyed shall be to the center line of such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or (b) the instrument evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation and not alone by bounding by a side line.

G.L. c. 183, §58 (emphasis added). Put briefly, the Millens contend that the statute applies to that deed because the land it conveys abuts the 16.5' Wide Right of Way and, by operation of the statute, the way is now theirs in its entirety because Ms. Johnson did not own the land on its other side. What that argument ignores is that the Johnson to McKay deed does evidence a "different intent", and that every subsequent deed of the property reflects so. That "different intent" is shown in the 1946 deed itself, even before its 1948 clarification, by the specification of the square footage being conveyed (5,498 rather than the 6,431 that would have included the Right of Way), by the metes and bounds footage measurements that stop at the line of the Right of Way, and then in the explicit language of the 1948 confirmatory deed that plainly states it was given:

to correct and clarify the description of said premises in a prior deed from the grantor to the grantees herein named, dated June 28, 1946, recorded with said Deeds, Book 3470, Page 217 [the 1946 Johnson to McKay deed], in which prior deed one of the courses of the northeasterly boundary is erroneously described as 54 feet, but should have been described as 37.5 feet, more or less, as herein described, because the right of way 16.5 feet wide was not intended to be included in the granted premises.

Confirmatory Deed, Johnson to McKay (Aug. 9, 1948) (Trial Ex. 10), recorded at the Essex (South) Registry of Deeds in Book 3617, Page 291 (Aug. 10, 1948) (emphasis added). See Hickey v. Pathways Ass'n, Inc., 472 Mass. 735 , 744 (2015) ("[T]he common-law presumption that a grantor of property abutting a way also conveys the fee to the center of the way is not an absolute rule of law irrespective of manifest intention, but is merely a principle of interpretation adopted for the purpose of finding out the true meaning of the words used.

[T]he underlying principle on which [all the cases] rest is that the intent of the parties in each instance was ascertained from the words used in the written instrument interpreted in the light of all the attendant facts. That is the general principle governing the interpretation of deeds.") (internal citations and quotations omitted).

The Millens contend that the 1948 confirmatory deed is ineffective because the land had already been conveyed. But that contention is wrong, for two reasons. First, the confirmatory deed corrects an obviously mistaken description in the earlier one and explains why it was a mistake ("because the right of way 16.5 feet wide was not intended to be included in the granted premises"). See Scalpen, 187 Mass. at 76 (confirmatory deed takes place of former conveyance). Second, the deed chain shows that both the McKays and their subsequent grantee (von Rosenvinge) knew of the mistake, why it was mistaken, and reflected that in their deeds even before the confirmatory deed was put on record. Both the McKays' deed to von Rosenvinge (Jul. 15, 1948) (Trial Ex. 8) and von Rosenvinge's deed to McCarthy (Aug. 7, 1948, Trial Ex. 9 put on record August 16, 1948 after the confirmatory deed was put on record (Aug. 10, 1948), likely because its recording was waiting for the confirmatory deed to go first) acknowledge that the land conveyed to them did not include the 16.5' Right of Way through (1) their correction of the length of the boundary line even before the 1948 Johnson to McKay confirmatory deed did so, and (2) their citation of the Johnson to McKay deed, which now incorporated the 1948 clarification through the Registry's marginal notation, as the source of their title. This knowledge, and their actions in light of it, show their assent, clearly and convincingly. See Juchno v. Toton, 338 Mass. 309 , 311 (1959) (acceptance of deed may be implied from grantee's conduct); McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 699-700 (2010) (discussing conduct showing grantee's assent to deed reformation). The fact that the fee in the 16.5' Wide Right of Way was intended to be retained, and was retained, by Ms. Johnson is further confirmed by the subsequent deed of her then-successor conveying the Right of Way to the then-owner of the George parcel, where it became "Parcel Two" on the George parcel's subsequent deeds, including Ms. George's. [Note 16]

In sum, the Millens do not have a fee interest or an easement interest in the 16.5' Wide Right of Way. Having decided the question on the grounds set forth above, I need not and do not reach the defendants' alternative argument that Ms. George and her predecessors adversely possessed whatever fee interest the Millens may have had in the area and extinguished any easement rights to use it.

The Millens Do Not Have an Easement to Their Property Over the Pardees' Land

The Millens claim that the 15'-wide easement over the Pardees' property from the 16.5' Wide Right of Way to Granite Street, currently benefiting the Condominium and George properties and used by Ms. George and the Pardees as their common driveway, also benefits them and, in addition, extends from its end point at the far end of the 16.5' Wide Right of Way to the edge of their property. Both of these contentions are wrong.

Ms. George has the benefit of the easement because it was expressly granted to her predecessors, the Andersons, by the then-owner of the Pardee land, Ms. Goodwin, in connection with their purchase of their land from her. See Trial Ex. 3. The Condominium has the benefit of the easement because it was expressly reserved by the then-owner of the Pardee land, Ms. Goodwin, at the time Ms. Goodwin conveyed the Pardee land to Ms. Johnson while retaining the Condominium parcel for herself. See Trial Exs. 1-4.

The Millens contend that the 15' easement has its origins prior to the Johnsons' purchase of the land from Ms. Goodwin, and that that easement, at that previous time, went all the way from Granite Street to and over their land as far as the then-Cleaves, now Clarke property

abutting them on the west. Whatever the merits of that argument, which I need not and do not decide, it is irrelevant today. When the Johnsons purchased the Goodwin land the Millens' "L", the Pardee property, and the 16.5' Right of Way parcel that is now part of the Ms. George's

all pre-existing easements over any part of that land that benefited another part, which would include any pre-existing easement over the now-Pardee parcel that arguably benefited the "L", ended by merger. [Note 17] Any such presently-existing easement would have had to be created anew, either expressly or by implication. No new express easements were created that benefited the "L", [Note 18] and none can be implied. Whatever "necessity" existed for the previously landlocked Lot "B" ended when it merged with Lot "A" and thus achieved frontage on Landmark Lane. See Hart, 222 Mass. at 414; Viall, 14 Gray [80 Mass.] at 127. No "common scheme" easement can be implied because the Partition Plan clearly divides the land into separate parcels, each with clear boundaries, and shows no such easement across them. [Note 19] See Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006) (easements implied from their being shown on a plan; here the plan shows no such easements other than Landmark Lane). And the Millens' theory that an easement to their property over the Pardees' land can be implied from long-existing prior use that continued post-conveyance, fails for lack of proof of such use. [Note 20] Indeed, as the basis for their argument that that easement should be deemed extinguished to the extent it burdens their land for the benefit of their western abutters, they themselves contend it has received no use at all.

Their implied easement theories also defy logic and are contrary to the attendant circumstances, which both show that such an easement could not have been intended. "The origin of an implied easement whether by grant or reservation

must be found in a presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable." Reagan, 446 Mass. at 458 (internal citations and quotations omitted). There is no such easement on the Partition Plan. Once Lots "A" and the conveyed part of Lot "B" merged (together forming the now-Millen property), they had frontage on Landmark Lane and thus no need for any other access. Putting an easement across the entire length of the Pardee land, far beyond where it otherwise had to be (i.e., beyond the location of the express easement granted to the Condominium and now-George parcels, which ended at the far edge of the 16.5' Wide Right of Way), makes no sense whatsoever since it would have occupied a considerable amount of the Pardee land, significantly lessening its use and market value. Had such an easement truly been intended, the McKays would have insisted that it be expressly and specifically stated in their deeds.

In sum, the Millens have no rights in the 15' easement, and no right to have it extended to the edge of their land. Having decided this issue on these grounds, I need not and do not reach the defendants' arguments that, if the Millens had rights to the 15' easement, those rights have been abandoned or lost.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, subject to the above-referenced updated and complete review of the Millens' record title and matters not in issue during the trial by the Land Court's in-house Title Examiners and Surveyors, [Note 21] the Millens have established good title, suitable for registration, to the land set forth on their Petition Plan 43479-A, with the exception of the area shown as the 16.5' Wide Right of Way.

The Millens do not have any right, title or interest in the 16.5' Right of Way fee, easement, or otherwise; no right to use the existing 15'-wide easement on the Pardees' land (which only benefits the Condominium and George properties); no right to have that easement further extended over the Pardees' land to the edge of Millens' property line to benefit the Millens' property; and no right to an easement over any other part of the Pardee or George parcels. For purposes of appeal, this Decision is the "judgment" on those issues. [Note 22]

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] For ease of reference, I refer to this parcel hereafter as the "L".

[Note 2] Deed, Bross to Millen (Dec. 3, 2004), recorded at the Essex (South) Registry in Book 23709, Page 159 (Dec. 3, 2004) (Trial Ex. 24).

[Note 3] This area is shown on the Millens' Petition Plan (Plan 43479-A) as "16.5' Wide Right of Way." The 16.5' Wide Right of Way was created in 1932 for the benefit of the parcel to its south (84 Granite Street) (Trial Ex. 4), now owned by the Colburn Homestead Condominium Trust (the "Condominium"), and continues to benefit that parcel today. As explained more fully below, contrary to their claims, the Millens have no fee interest in the 16.5' Right of Way area (it is currently owned by defendant Ruth George), nor does their property have any easement rights in it either explicitly, implicitly, or by prescription.

[Note 4] Deed, Cadigan to George (Nov. 29, 2005), recorded at the Essex (South) Registry in Book 25164, Page 513 (Dec. 7, 2005) (Parcel Two) (Trial Ex. 25).

[Note 5] See n. 3, supra. No one contests the Condominium's easement rights. At present, the Condominium uses it only for foot traffic.

[Note 6] This review, including an update of the Millens' title (last examined in 2013), will be conducted by the in- house Land Court Title Examiners and Surveyors as part of the Land Court's usual final Registration process. This is done, among other reasons, to ensure that the Certificate of Title accurately reflects mortgages, utility easements, creditor liens, etc. When that review is completed, a final judgment of registration will issue. See Rettberg v. Henry, 8 LCR 390 , 390 (2000). For purposes of appeal, the "judgment" on the merits of the issues contested at trial and decided herein is this Decision. See Tyra v. Hall, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 87 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 , 2015 WL 774515 at *1, n. 5 (2015).

[Note 7] See colloquy with counsel at the beginning of trial.

[Note 8] As previously noted, the fence was put there by Ms. George. According to the testimony at trial, there had been a line of bushes there beforehand demarcating the boundary.

[Note 9] "Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years." Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). The claimant has the burden of proving each of the elements of adverse possession in order to prevail, Mendonca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968), and must do so by "clear proof of an actual occupancy, clear, definite, positive, and notorious." Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 210 (1853). "In weighing and applying the evidence in support of such a title, the acts of the wrongdoer [the claimant] are to be construed strictly," id., and "if any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Mendonca, 354 Mass. at 326 (emphasis added).

The Millens did not offer any proof that satisfied any of these elements.

[Note 10] For ease of reference, when I refer to Ms. Goodwin's conveyances I also include those made by her estate.

[Note 11] The fee in the 16.5' Wide Right of Way was conveyed to the Andersons by its then-owner, Tilda Sepich (whose title to it derived from Hulda Johnson), in 1962. Ms. George purchased all of the former Anderson property, including the fee in the 16.5' Right of Way, in 2005.

[Note 12] Ms. Johnson ultimately acquired all of her husband's interests. All parts of the land they were deeded by Ms. Goodwin were titled in Ms. Johnson's name (and thus merged) by the time of her Partition Plan (May 31, 1945), a copy of which is attached hereto as Ex. 2. For purposes of this case, the significance of that merger is that, as a matter of law, it extinguished all pre-existing easements burdening one part of her land for the benefit of another part (e.g., all pre-existing easements, if any, over the Pardee property for the benefit of the Millen land). See n. 14 and the further discussion below. Ms. Johnson's husband, J. Leonard Johnson, recognized that merger would have this effect when he conveyed his interest in the Goodwin land to her on November 30, 1932. See Trial Ex. 5 ("the above-described premises are conveyed subject to and with the benefit of all rights of way and easements as set forth [in his deed from Ms. Goodwin] so far as said rights of way exist or may continue to exist after this conveyance is made.") (emphasis added).

[Note 13] For ease of reference, I refer to the 15' wide easement as being on the Pardee property, although half of its width in the section abutting the George property may be owned by Ms. George pursuant to the Derelict Fee Statute (G.L. c. 183, § 58). I need not and do not decide that ownership as it is outside the scope of these proceedings which are limited to an adjudication, and resultant registration, of the title, boundary and appurtenant rights (both burdening and benefiting) the Millen property. Whether the 15' wide easement is entirely on the Pardee property, or part on that property and part on Ms. George's, is immaterial to the adjudication of the Millens' rights in it. As discussed more fully below, they have no such rights.

[Note 14] Under the common-law doctrine of merger, easements are extinguished "by unity of title and possession of the two estates [the dominant and the servient], in one and the same person at the same time." Ritger v. Parker, 8 Cush. [62 Mass.] 145, 146 (1851). "When the dominant and servient estates come into common ownership there is no practical need for the servitude's continued existence, as the owner already has the full and unlimited right and power to make any and every possible use of the land.' " Busalacchi v. McCabe, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 493 , 498 (2008), quoting from Ritger, supra at 147. Once extinguished, easement rights cannot be "revived" merely by severing the dominant and servient estates. Cheever v. Graves, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 601 , 607 (1992). They "must be created anew by express grant, by reservation, or by implication." Id. (internal citation omitted).

[Note 15] That deed (Trial Ex. 7) contains a facial ambiguity which was later corrected in an Aug. 10, 1948 confirmatory deed (Trial Ex. 10). But even before the confirmatory deed was created to make that correction a matter of record (see Scalpen v. Blanchard, 187 Mass. 73 , 76 (1904) (confirmatory deed "takes the place of the original deed, and is evidence of the making of the former conveyance as of the time when it was made")), the correction it made was acknowledged by the grantees of that land. The ambiguity in the 1946 deed was its reference to the land being conveyed as "Lot B" (which would have included the 16.5' Right of Way area) rather than as a portion of Lot B, and its mis-statement of the length of one of the boundary lines of the portion of Lot B being granted as 54' (which would have extended to the other side of the Right of Way), rather than the correct length of 37.5' (which would not) (this error is obvious because the lot boundaries with the incorrect measurement do not "close", i.e. all connect with each other). That Ms. Johnson intended to retain the fee in the Right of Way area and not include it in the conveyance to the McKays is apparent from the other metes and bounds measurements in the deed (the ones on the south, which went only as far as the line of the right of way), the description of the boundary on that side as by the right of way, the specification of the amount of square footage being conveyed as 5,498 square feet, rather than the total for the entirety of Lot B (6431 square feet) (the difference between the two is the square footage of the Right of Way) and the confirmatory deed itself (correcting the measurement "because the right of way 16.5 feet wide was not intended to be included in the granted premises") (Trial Ex. 10).

The McKays' subsequent deed of the property to its next grantee made the correction even before the confirmatory deed was created (see McKay to von Rosenvinge, Jul. 15, 1948, which has the correct boundary measurement -- 37.5' -- and the handwritten notation that only a part of Lot B was being conveyed), and so does von Rosenvinge's own deed out shortly thereafter (see von Rosenvinge to McCarthy, Aug. 9, 1948, recorded Aug. 16, 1948) (37.5').

The Johnson to McKay Confirmatory Deed (Aug. 9, 1948, recorded Aug. 10, 1948 before the von Rosenvinge deed out) makes the correction explicit in the chain of title by stating that its purpose was to "correct and clarify the description of [the] premises", and did so by giving the correct 37.5' measurement and explaining that the clarification was "because the right of way 16.5' wide was not intended to be included in the granted premises." (Trial Ex. 10). The Registry of Deeds put this correction and explanation on the original (1946) deed by marginal notation ("See B. 3617 P. 291" the book and page of the 1948 confirmatory deed) so that anyone doing a title search would immediately see it and be on notice. Thus no subsequent grantee, including the Millens, can claim to have been misled or justifiably to have relied on anything other than that their property did not include the Right of Way and that the Right of Way had been expressly excepted from their title chain. See Scalpen, supra.

[Note 16] See Deed, Sepich to Anderson (Jun. 1, 1962), recorded at the Essex (South) Registry of Deeds in Book 4934, Page 339 (Jun. 21, 1962).

[Note 17] See n. 14. See also the testimony of attorney J. Michael Faherty, the defendants' expert witness. Trial Transcript, Vol I at 155-157. I accept, credit, and am persuaded by all of his testimony.

[Note 18] See Trial Ex. 6, Ms. Johnson's conveyance of Lot "A" to the McKays (May 31, 1945) which contains no express easements; Trial Ex. 7, her conveyance of part of Lot "B" to the McKays (the "toe" of the "L") (Jun. 28, 1946) which contains no express easements; and Trial Ex. 10, her confirmatory deed to that part of Lot "B" (Aug. 9, 1948) which contains no express easements. The first reference to easements in any of the deeds after all the land merged into Ms. Johnson's ownership is in the deed to Lot "A" and that part of Lot "B" from the McKays' successors, the McCarthys, to Robert Bales (Jun. 4, 1956) (Trial Ex. 11) (the next grantee in the Millens' chain of title) which contains the language, "There is also conveyed all rights of way and easements which may be appurtenant to the granted premises in Landmark Road [then private, now public] and any other rights of way which adjoin the granted premises." (emphasis added). The important word is "may" because, aside from rights in Landmark Lane, there were no other easements to grant because of the prior merger. As the defendants' expert witness, attorney J. Michael Faherty, testified, the inclusion of such catchall language in deeds with the qualifier "may" was "a way I don't want to call it sloppy, but it's lazy. Rather than articulating exactly what it is, it basically says whatever you have out there you've got and it's in there." Trial Transcript, Vol. I at 115. As he noted, due to the prior merger and the fact that the Johnson deeds created no express easements afterward, there were, in fact, "no rights of way of record" appurtenant to this land to convey. See Trial Transcript, Vol I at 115, 132, and 155-157. The deeds subsequent to the McCarthys' carried forward that "may" language simply to mirror the McCarthys' deed to show that they were conveying the entirety of the McCarthys' interest, whatever it was.

[Note 19] As previously discussed, the Partition Plan shows the 16.5' Right of Way because it benefited Ms. Goodwin's remaining land, not any of Ms. Johnson's property, and as an identifier of a land area whose fee she was retaining when she conveyed Lot B to the McKays.

[Note 20] "The burden of proving the existence of an implied easement is on the party asserting it." Reagan, 446 Mass. at 458.

[Note 21] See n. 6.

[Note 22] See n. 6.

JONATHAN MILLEN and HELEN MILLEN v. ANNE PARDEE, HARRY PARDEE III, and RUTH GEORGE.

JONATHAN MILLEN and HELEN MILLEN v. ANNE PARDEE, HARRY PARDEE III, and RUTH GEORGE.