Introduction

Plaintiff Anthony Pelullo as trustee of the Pelullo Family Nominee Trust owns the single family residence at 40 Oxford Street in Natick. [Note 1] Over Mr. Pelullo's objections, all timely filed and diligently prosecuted, a house was built at 15 Upland Road in Natick, directly across that

street from Mr. Pelullo's property. Despite full knowledge of those objections and the resulting lawsuits, [Note 2] defendants Michael and Lisa Ware purchased the house and currently live there with their children. Mr. Pelullo is correct that the house violates the zoning bylaw. The question now before me is whether it should be torn down.

In brief, the situation is this. Neither the building permit for construction of the house, nor the subsequent certificate of occupancy, should have been granted. Although the house itself meets all setback requirements (i.e., it is sufficiently distant from each of the lot's boundary lines, including the one closest to Mr. Pelullo), the lot on which it was built fails the lot depth requirement [Note 3] (it is too narrow and shallow), and not just by a little. Under the bylaw, it needs to be at least 125' deep. Instead, it is only 70.9'. See Pelullo v. Natick Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 20 LCR 467 (2012), aff 'd 86 Mass. App. Ct. 908 (2014). Thus, without a variance, the lot is unbuildable.

The Wares applied for such a variance, which the Zoning Board granted. As previously ruled in this proceeding however, the lot does not meet the criteria for a variance [Note 4] and, if Mr. Pelullo has standing to challenge the variance, it is subject to being invalidated. See Mem. & Order on Cross Motions for Summary Judgment (Feb. 28, 2014). A trial was held to determine if Mr. Pelullo had such standing.

Standing requires the plaintiff to show "aggrievement." Once (as here) the presumption of aggrievement granted to abutters and abutters to abutters within 300' has been rebutted, [Note 5] the plaintiff has the burden to show, by direct facts supported by credible evidence, that he or she either has or will suffer an injury or injuries "related to a cognizable interest protected by the applicable zoning law" that is "special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community." See Murrow v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of the City of Somerville, 93 Mass. App. Ct. 1119 (2018), 2018 WL 3402106 at *2 (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28; internal citations and quotations omitted). "[M]ore than minimal or slightly appreciable harm" must be shown. Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted). "The adverse effect on a plaintiff must be substantial enough to constitute actual aggrievement such that there can be no question that the plaintiff should be afforded the opportunity to seek a remedy." Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted). Importantly, "it is not enough for a plaintiff to simply identify an interest protected by the by-law; the plaintiff must put forth credible evidence to substantiate claims of injury to that legal interest." Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted). "In other words, it [is] not enough for a standing analysis to simply say that density provisions were violated." Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted). The plaintiffs must show a direct, specific impact on themselves that both arises from that density violation and is "special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community." Id. at *2 (internal citations and quotations omitted).

After hearing the evidence at trial, I found and ruled that Mr. Pelullo had standing, but only from a single impact: headlights shining in the windows of his home from cars exiting the Wares' driveway at night. See Pelullo v. Natick Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 2014 WL 6792558 (Mass. Land Ct., Dec. 3, 2014). All of the other impacts he alleged were either minimal or "concerns of the rest of the community" that were not "special and different" to him. Id. The case thus proceeded to its current phase: the appropriate remedy. See Mem. & Order on the Question of Appropriate Relief (Jul. 13, 2015).

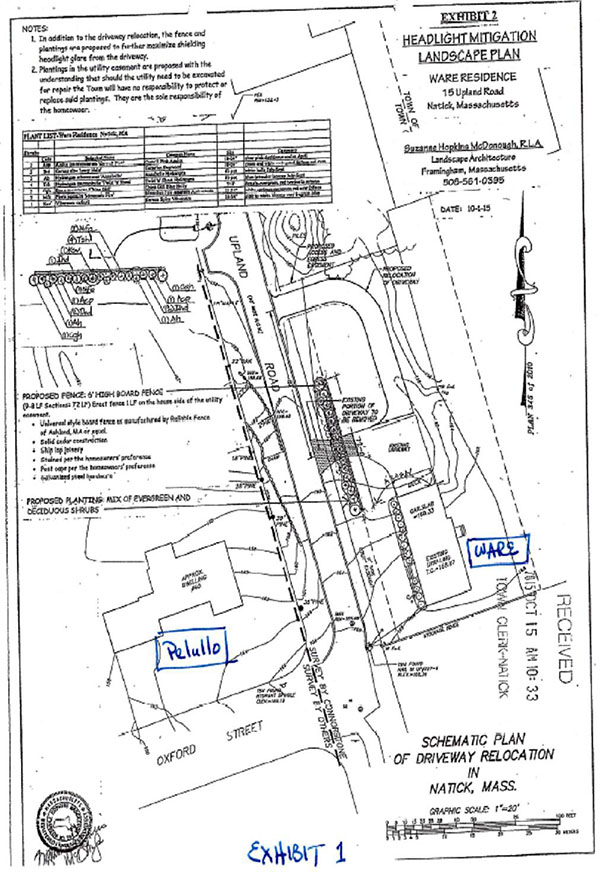

Not every zoning violation warrants a tear-down. See Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 394 , 405 (2012). In DelPrete v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Rockland, 87 Mass. App. Ct. 1104 (2015), 2015 WL 442974 at *1-*2 (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28), citing Sheppard and other precedent, the Appeals Court recognized that there is "some discretion to grant an equitable alternative to a tear-down order" and remanded the matter to the trial court to "consider the balance of factors that may enter into such a calculus," among them "whether a tear-down would cause substantial hardship, whether [the owner of the structure subject to tear-down had] greatly changed his position as a result of actions taken by a town official and whether such reliance was reasonable, whether there is injury to the public interest if the house remains standing, and finally, whether the parties acted in good faith throughout the process." Id. Following the guidance of DelPrete, I thus remanded the case to the zoning board to consider those factors plus an additional related one: whether mitigation would eliminate the harm to Mr. Pelullo. [Note 6] This last was prompted by the Wares' submission of a driveway relocation and headlight mitigation landscape plan which proposed (1) an 82' shift in the location of the driveway exit so that it would be far down the street from the Pelullo home, [Note 7] (2) a 6' high board fence between the driveway and the Pelullos, [Note 8] and (3) a line of closely-planted evergreen and deciduous shrubs along that fence as further shielding. See Ex. 1 (attached). According to the Wares, this would eliminate all headlight intrusion into the Pelullo residence originating from their home.

The board held hearings and, in addition, took a nighttime view from inside the Pelullo house. During that view, the board members watched cars with their headlights on "high-beam" entering and exiting the Ware driveway from the locations of both the present driveway and the proposed new one. Based on that evidence, the board concluded that the "DelPrete" factors had been satisfied, the re-located driveway eliminated headlight intrusion into the Pelullo home, and that "the driveway relocation plan, together with [the] additional landscaping and fenced barrier as put forth in the Landscaping Mitigation Plan that was submitted by the Wares[,] represents a reasonable solution to the 'harm' upon the Pelullo property and weigh[s] heavily in favor as an equitable alternative to a tear down." Zoning Board Decision at 4 (Oct. 15, 2015). They thus voted unanimously in favor of the driveway relocation plan as "an equitable alternative." Id.

Mr. Pelullo appealed that Decision to this court, and a de novo trial was held before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, and my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, I find and rule as follows.

Facts and Analysis

These are the facts as I find them after trial, and the legal conclusions I base on those facts.

Background

The Ware property is located directly across the street (Upland Road, a private way) from the Pelullo home. [Note 9] See Ex. 1. It was once part of a larger tract of land that was acquired in 2002 by H&R Development LLC and then subdivided. Development of those subdivided lots required improvements to Upland Road (elevation and paving) so that it could be used as frontage. Mr. Pelullo opposed those improvements, but they ultimately went forward with certain modifications (the off ramps previously referenced in this Decision, see n. 7) to ensure that the Pelullo property maintained access to Upland Road that was substantially the same or better than what it had before. See Pelullo v. H&R Development LLC, Land Court Case No. 10 MISC. 431229 (KCL), Decision (Jan. 14, 2013).

H&R obtained a building permit for construction of the house now owned by the Wares and, over Mr. Pelullo's objections, that building permit was upheld by the zoning board. However, both the building inspector and the zoning board were wrong. The building permit should not have been granted because the lot lacked the depth required by the zoning bylaw, and this court, affirmed by the Appeals Court, so held. See Pelullo v. Natick Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 20 LCR 467 , 2012 WL 4714521 (Mass. Land Ct., Oct. 3, 2012), aff 'd 86 Mass. App. Ct. 908 (2014).

After the house was built and while the litigation concerning the validity of its building permit was still pending, H&R became insolvent and its lending bank, the Needham Cooperative Bank, foreclosed on the property. The Bank then sold it to Natick Upland LLC and, in turn, Natick Upland transferred it to its sole member/manager, Paul Croft, and Mr. Croft sold it to the Wares. The Wares' purchase was with full knowledge of the pending litigation as reflected in their purchase and sale agreement. [Note 10] Mr. Croft, however, agreed that "[i]n the event any post-closing decision or ruling by the Land Court, or other court of further appellate jurisdiction, adversely impacts the actual continued use of the premises or its actual future marketability, Seller [Mr. Croft] agrees to re-purchase the premises from Buyer [the Wares] at the identical purchase price within thirty (30) days of such final adjudication, all appeals having been exhausted[,] under the terms and conditions of a collateral agreement agreed to by the parties." Unfortunately for the Wares, Mr. Croft became insolvent in September 2015 and his indemnity is now worthless. As noted above, the variance they subsequently obtained from the lot depth requirement is invalid, Mr. Pelullo has standing to challenge the variance, and the house must be torn down unless there is an "equitable alternative" to tear-down or grounds to dismiss Mr.

Pelullo's case.

The DelPrete and Other Factors

"The case law recognizes that tear down orders do not necessarily follow every determination of a zoning violation, and that a court may consider equitable factors and the potential availability of money damages as an appropriate alternative remedy." Sheppard, 81 Mass. App. Ct. at 405 (internal citations omitted). DelPrete identified those factors as including "whether a tear-down would cause substantial hardship, whether [the homeowner] greatly changed his position as a result of actions taken by a town official and whether such reliance was reasonable, whether there is injury to a public interest if the house remains standing, and finally, whether the parties acted in good faith throughout this process." DelPrete, 2015 WL 442974 at *2. Sheppard adds a fifth factor, the availability of an "appropriate alternative remedy" to a tear- down, which I also included in my remand to the board, phrased as follows: whether, if the harm to Mr. Pelullo from the zoning violation could be completely eliminated, tear-down should still be ordered. As previously noted, the focus was on Mr. Pelullo because he was the only complaining party, the zoning board itself was fully in favor of the house, and no direct effect on any other property or what the Supreme Judicial Court has called the "public advantage" was alleged or shown. See Marblehead v. Deering, 356 Mass. 532 , 537-538 (1969). I analyze each of these factors in turn.

Substantial Hardship

"In a tightly limited line of cases, our courts have said that such a substantial hardship [tearing down a fully constructed house], when considered along with relevant factors favoring leniency, may in exceptional cases call for a remedy short of demolition." DelPrete v. Rockland Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 2016 WL 1358965 at *11 (Mass. Land Ct. 2016) (the DelPrete case after remand to the trial court). Tearing down the house, losing everything they have spent on it, and moving all of their family life to a new location is clearly a substantial hardship for the Wares. But this is so in almost any tear-down of an owner-occupied residence and, solely by itself, is not enough to avoid demolition. See DelPrete, 2016 WL 1358965 at *12. There must be additional "relevant factors" to avoid such an outcome, particularly where, as here, the homeowners purchased the property with full knowledge of that risk. See Sterling Realty Co. v. Tredennick, 319 Mass. 153 , 158 (1946) (affirming order directing removal of structure because "[t]he defendants acquired the property with notice of the restrictions and took their chances as to the effect of their conduct upon the plaintiff's rights."); Stewart v. Finkelstone, 206 Mass. 28 , 38 (1910) (same). The Wares' purchase and sale agreement specifically references the pending litigation on the validity of the building permit, and even identifies the problems at issue: "(1) lot depth and (2) use of Upland Road for access and frontage."

Reliance on Actions by Town Officials

The building inspector issued the building permit for the house and the zoning board upheld its issuance, both over Mr. Pelullo's objections. The Wares relied on those decisions, at least to a point (they insisted on getting a buy-back indemnity, unfortunately now worthless due to their seller's insolvency), and reasonable reliance on actions by town officials can be a factor in avoiding a tear-down. See Marblehead v. Deery, 356 Mass. 532 , 537-538 (1969). But here there could be no reasonable reliance because the building inspector and the board were so obviously wrong. Lot depth is measured front to back. That is what "depth" is. Depth is not measured diagonally across a lot, and certainly not where, as here, a lot is long and shallow. See Pelullo v. Natick Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 20 LCR 467 , 2012 WL 4714521 (Mass. Land Ct., Oct. 3, 2012), aff 'd 86 Mass. App. Ct. 908 (2014). Because there was no way to add depth to their lot (their seller, Mr. Croft, did not own any of the land behind them, all of which was occupied by other homes), the Wares were fully aware, or should have been aware, that the only way to correct the zoning violation was by demolishing the house. See DelPrete, 2016 WL 1358965 at *11 ("The very presence of the structure on a sub-sized lot which never should have been built upon constitutes a clear violation of the zoning law, and if the lot cannot be made bigger, then only by removing the structure can that violation be corrected."). The risk of that occurrence was thus knowingly assumed. This is not necessarily fatal, though. As discussed below, when weighing all the equitable factors together, the most important and, in this case, the most decisive is whether a full and complete "alternative remedy" truly exists. This may indeed be a rare occurrence, but it exists here.

Injury to the Public Interest

DelPrete requires consideration of the public interest. In this case, the public interest is the proper enforcement of the zoning bylaws. See DelPrete, 2016 WL 1358965 at *13 (citing Wyman v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Grafton, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 635 , 638-639 (1999)). "Without concerted enforcement, the integrity of the zoning laws, and the willingness of those subject to them to follow them, will be diminished." Id.

Here, the zoning violation is neither minor nor a "technicality." It was also obvious. The Ware house is on a lot significantly less than the required depth. Lot depth requirements for single family residences are controls on density, with the goal of protecting the surrounding neighborhood. Thus, compliance with those requirements is an important public interest.

I cannot ignore, however, the consistent support the Ware house has had from the zoning board. Its decisions on the original building permit, and then on the variance, were wrong and clearly so. But they nonetheless reflect the board's sense of what will fit into the community. It is significant that the only opposition to the Ware house has come from Mr. Pelullo. See Sheppard, 81 Mass. App. Ct. at 405 (declining to order a tear-down with the comment, "Notably, this is not a case where the public entity administering the applicable zoning requirements is seeking enforcement. Instead, the board has consistently supported the construction of McGarrell's new house

"). No harm to anyone else, nor any direct harm to the public, has been alleged or shown. As noted above, the focus can thus be on Mr. Pelullo alone.

Exhaustion of Alternative Means to Achieve Zoning Compliance

Absent countervailing factors, before proceeding with enforcement of a tear-down order, a town may decide to provide the landowner with an opportunity to correct the zoning violations. See DelPrete, 2016 WL 1358965 at *13, citing Building Inspector of Falmouth v. Haddad, 369 Mass. 452 (1976) (owners who built a motel after receiving a permit to build a single-family residence had the opportunity to obtain "any permit necessary" to either change the structure so it fit a permitted use as of right or through special permit before being forced to demolish it); Sterling v. Poulin, 2 Mass. App. Ct. 562 (1974) (landowner using property in rural residential and farming district for commercial purposes was entitled to opportunity to convert building at issue to legal use permitted by the ordinance prior to the order requiring demolition of the structure); and Stow v. Pugsley, 349 Mass. 329 , 335 (1965) (court ordered structure that violated bylaw to be removed unless shown on a further hearing to be adapted and intended for a permitted use)).

Here, the only zoning alternative that would correct the violation is a variance. The Wares applied for and received such a variance but, as previously held, a variance cannot validly be granted. Put simply, the lot does not meet the requirements. See G.L. c. 40A, §10; Mem. & Order on Cross Motions for Summary Judgment (Feb. 28, 2014). Zoning alternatives have thus been exhausted.

Good Faith

Mr. Pelullo has proceeded throughout with diligence and good faith, asserting his opposition, in timely fashion, at every relevant step. He has been completely transparent, and sprung no surprises on the Wares. They cannot complain of being sandbagged.

The Wares have also proceeded in good faith. They bought the house knowing of the peril of doing so. But they have lived there as good neighbors and, to their credit, have tried to address Mr. Pelullo's issues. The zoning board found that the Ware's headlight mitigation landscape plan fully eliminates the headlight intrusion into the Pelullo home and, based on the evidence admitted in this proceeding, I fully concur and so find. Mr. Pelullo will suffer no harm protected by the zoning bylaw once that plan is implemented.

Evaluation of the Factors

There are at least three ways to evaluate the effect of the complete mitigation of the harm to Mr. Pelullo. One is that his "standing" to object to the variance no longer exists because he would no longer be "aggrieved." The second, for the same reason, is that his case would now be "moot." The third way, and I believe the correct one, is to view the elimination of harm, coupled with the board's concurrence in this finding and its full support of the house, as a fully adequate and appropriate "alternative remedy" to demolition once the headlight mitigation landscape plan has been incorporated into an enforceable judgment of the court. For the reasons set forth below, I take the third path.

It is tempting to view the elimination of the harm to Mr. Pelullo as the elimination of his standing or, perhaps, as "mooting" his case, resulting in its dismissal. But the problem with that, at least as applied in these circumstances, is this. Mr. Pelullo had standing to bring this case when he filed it, and the existing case law holds that "[a] court is not ousted of jurisdiction by subsequent events jurisdiction once attached is not impaired by what happens later."). Landreth v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Truro, 88 Mass. App. Ct. 1115 (2015), 2015 WL 7878549 at *3 (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) (internal citations and quotations omitted). Zoning claims that began with standing to assert them, and then are subsequently addressed when standing for that claim no longer exists, are analyzed under the doctrine of mootness. [Note 11] See Porcaro v. Hopkinton, Mem. & Order on Defendant's Motion to Dismiss, 2001 WL 1809814 (Mass. Super. Ct., Dec. 19, 2001) (Giles, J.) (plaintiff no longer had interest in property and thus no personal stake in outcome of case; case thus dismissed). Where, as here, subsequent events have addressed the harm but a judgment may be needed to ensure that the harm is addressed, [Note 12] courts have not dismissed the case but rather entered such a judgment. See Bonfiglioli v. Walsh, Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order for Judgment, 2002 WL 31926476 (Mass. Super. Ct., Dec. 30, 2002) (Fabricant, J.) (need for setback variance mooted by modifications to house; court entered judgment vacating variance, thus ensuring it could not be used).

I thus find and rule that the case is not moot in the classic sense, i.e. moot no matter what, with dismissal as the proper remedy. Rather, it is moot in that there will be no harm to Mr. Pelullo so long, and only so long, as the Headlight Mitigation Landscape Plan driveway relocation, fence construction, and planting of evergreen and deciduous shrubs is fully implemented and maintained. Once that plan is fully implemented, and so long as it remains fully maintained, it eliminates the harm to Mr. Pelullo arising from the zoning violation and thus constitutes a fully adequate "alternative remedy" to tear-down. In sum, so long as it is in place, "no harm, no foul." Its implementation brings this within the "tightly limited line of cases" where, despite a clear zoning violation, demolition can be avoided, and I so find.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons and the reasons set forth in my previous memoranda in this case, [Note 13] I find and rule that the variance from the lot depth requirement granted to the Wares by the zoning board was erroneously issued, that Mr. Pelullo had standing to challenge that variance but only due to the headlight impact on his house, that that impact is fully mitigated by the Wares' Headlight Mitigation Landscape Plan, and thus that the implementation and maintenance of that plan is a fully sufficient alternative remedy to tear-down of the Ware house. The decision of the zoning board so finding is thus AFFIRMED, and the Wares are ORDERED to implement and maintain that plan. Mr. Pelullo's request that the house be torn down is DENIED. It may remain as long as the Headlight Mitigation Landscape Plan remains fully implemented.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

ANTHONY PELULLO as trustee of the Pelullo Family Nominee Trust v. SCOTT LANDGREN, LAURA GODIN, CHIKE ODUNUKWE, KEVIN POLANSKY and CHRISTOPHER SWINIARSKI as members of the Natick Zoning Board of Appeals that heard the variance application and request for zoning enforcement; SCOTT LANDGREN, DAVID JACKOWITZ, GARRET LEE, ROBERT HAVENER and JASON MAKOFSKY as members of the Natick Zoning Board of Appeals that heard the remand to consider "equitable considerations" with respect to the plaintiff's "tear down" request; MICHAEL WARE and LISA WARE.

ANTHONY PELULLO as trustee of the Pelullo Family Nominee Trust v. SCOTT LANDGREN, LAURA GODIN, CHIKE ODUNUKWE, KEVIN POLANSKY and CHRISTOPHER SWINIARSKI as members of the Natick Zoning Board of Appeals that heard the variance application and request for zoning enforcement; SCOTT LANDGREN, DAVID JACKOWITZ, GARRET LEE, ROBERT HAVENER and JASON MAKOFSKY as members of the Natick Zoning Board of Appeals that heard the remand to consider "equitable considerations" with respect to the plaintiff's "tear down" request; MICHAEL WARE and LISA WARE.