JOHN MOSS and AMY BORNER v. GARY LINGLEY and ANNMARIE LINGLEY as Trustees of the J.M.J. Realty Trust and TOWN OF WAYLAND, acting by and through its BOARD OF SELECTMEN, BOARD OF PUBLIC WORKS and CONSERVATION COMMISSION.

JOHN MOSS and AMY BORNER v. GARY LINGLEY and ANNMARIE LINGLEY as Trustees of the J.M.J. Realty Trust and TOWN OF WAYLAND, acting by and through its BOARD OF SELECTMEN, BOARD OF PUBLIC WORKS and CONSERVATION COMMISSION.

MISC 13-480577

April 6, 2018

Middlesex, ss.

LONG, J.

DECISION

Introduction

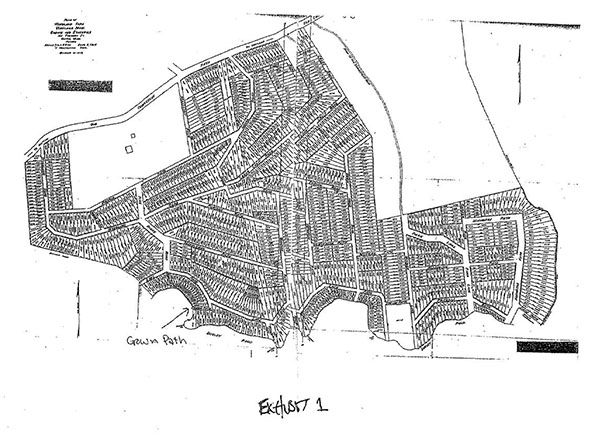

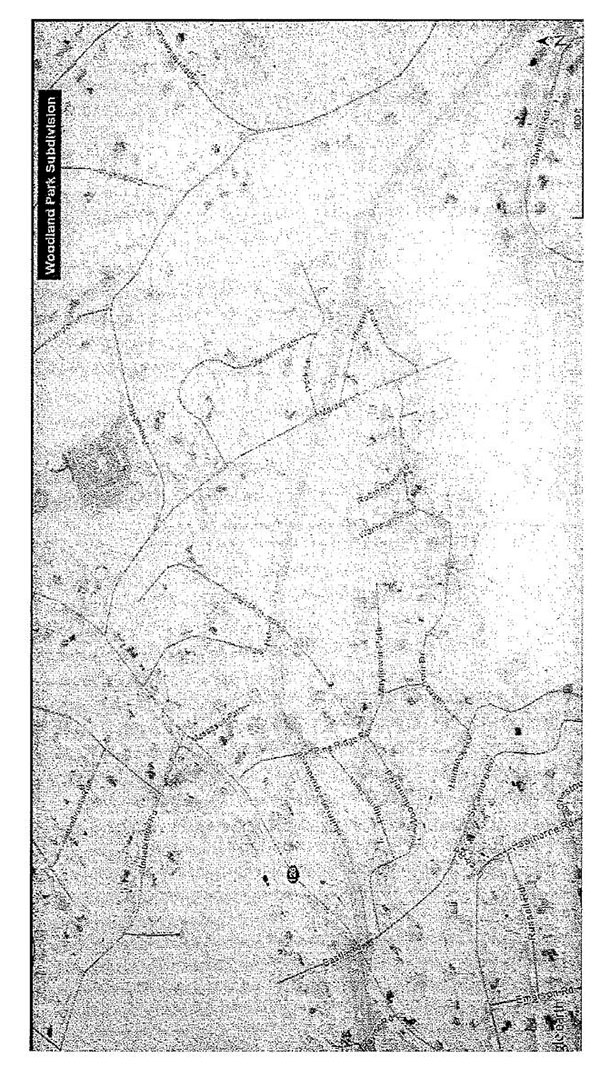

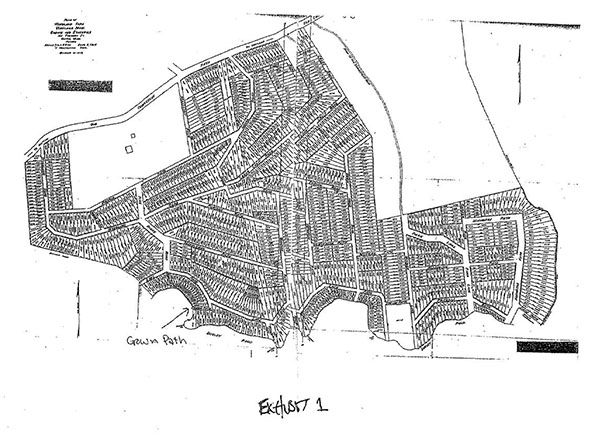

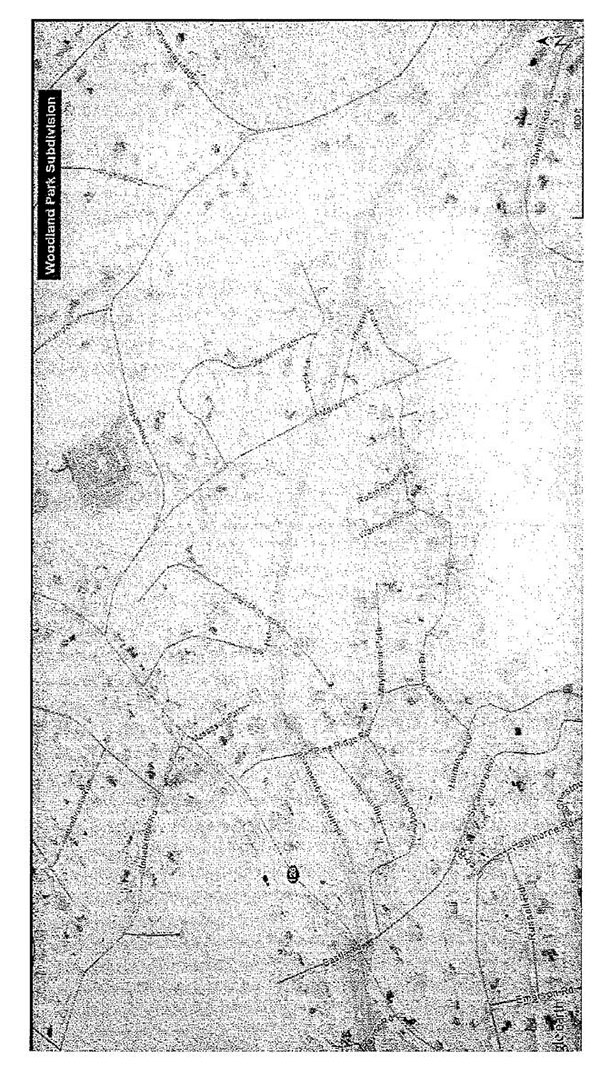

The plaintiffs, John Moss and Amy Borner, own the property at 50 and 54 Lake Shore Drive on Dudley Pond in Wayland. It is part of the Woodland Park Subdivision, which was laid out on a plan entitled "Woodland Park, Wayland, Mass." dated September 3, 1914 and recorded at the Middlesex South Registry of Deeds (the "1914 Plan"), a copy of which is attached as Ex. 1. That plan, however, has almost no relationship to how the area has actually developed. See Ex. 2 (present-day aerial photograph). The lots on the plan were combined into larger parcels before houses were built on them. [Note 1] Others were combined into extensive conservation areas. The Hultman Aqueduct to the Quabbin Reservoir took many more. As a result, many of the roadways shown on the plan were never built, and no steps have ever been taken to build them. See Ex. 2. In particular, the "Crown Path" roadway shown across the plaintiffs' property on the 1914 Plan has never been used or developed. It is, and has always been, only a "paper street" [Note 2] and has long-since been incorporated into the plaintiffs' property.

Despite this, and based solely on the existence of Crown Path on the 1914 Plan, both defendant J.M.J. Realty Trust and the Intervenor Defendant Town of Wayland have contended that they have the right to use Crown Path for access to Dudley Pond. The Trust has previously been defaulted, [Note 3] leaving only the town as an active defendant. [Note 4] The town has never used Crown Path for such access, has no need to do so, and has always used other routes to access the pond.

The plaintiffs contend that the town has no right to use Crown Path because, to the extent it ever had an easement to do so, that easement has long-since been abandoned. The town disagrees.

This case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and documents admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully explained below, I find and rule that abandonment has occurred, and thus that whatever easement rights previously existed for any of the town's parcels to use Crown Path now no longer exist.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

The Woodland Park Subdivision

The Woodland Park Subdivision plan laid out 969 lots on approximately eighty-five acres of land, with Dudley Pond to the south and Old Connecticut Path to the north. Nearly all of those lots have been combined into larger parcels. The 1914 Plan also depicts a network of roadways, most of which, like Crown Path, are only paper streets which have never been developed.

The Town's Property

The town owns the entirety of Dudley Pond. The town also owns, in whole or in part, 159 lots as shown on the 1914 Plan, which are presently configured as eleven parcels (collectively, Town Parcels 1-11) and administered by various town departments. [Note 5] Town Parcels 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 consist of deed-restricted conservation land and are administered by the town's conservation commission. Town Parcel 6, acquired by a taking for "highway purposes" (although not presently used as such), is administered by the town's department of public works. The town's board of selectmen administers Town Parcels 7, 8, 9, and 10 (acquired by tax lien foreclosures), as well as Town Parcel 11 (acquired by quitclaim deed). The Town Parcels are, for the most part, wooded, unimproved, and not presently in active use.

At issue is the town's claim of a right of way over Crown Path, which is based solely on the depiction of Crown Path on the 1914 Plan and the reference in certain of the town's deeds to the right to use the ways shown on that plan. [Note 6] As discussed more fully below, regardless of what easement rights may have existed on that basis, all such rights to the use of Crown Path have been abandoned.

The Plaintiffs' Property

The plaintiffs' property consists of thirteen (and a portion of a fourteenth) adjoining lots shown on the 1914 Plan. [Note 7] They acquired title to 50 Lake Shore Drive [Note 8] in 2006, and title to the adjacent property at 54 Lake Shore Drive in 2008. [Note 9] After purchasing 50 Lake Shore Drive, the plaintiffs demolished the existing house on the property, constructed a new one, and remodeled its garage. They subsequently demolished the house on 54 Lake Shore Drive and, with extensive landscaping, began using that parcel's land as part of their lawn. The two properties are thus now combined into a single parcel with a single dwelling. [Note 10]

The plaintiffs' property includes the fee to all of the land abutting Crown Path as depicted on the 1914 Plan. By operation of the Derelict Fee Statute, the plaintiffs own the entirety of the fee in Crown Path as well. [Note 11] See G.L. c. 183, § 58.

Crown Path

Crown Path has never been used or developed as a roadway. [Note 12] As shown on the 1914 Plan, it appears to extend from Lake Path (presently Lake Shore Drive) to Dudley Pond, between lots now owned by the plaintiffs. It is approximately two-hundred-and-twenty feet long, varies from nineteen to twenty-one feet wide, and has a hairpin turn near the street. On the ground, most of Crown Path is relatively flat, but toward Dudley Pond it slopes down and has a steep, rocky drop to the water.

Before the plaintiffs combined 50 Lake Shore Drive and 54 Lake Shore Drive into one residence, most of Crown Path was used as part of 54 Lake Shore Drive's side yard. The front portion of the remainder was used as part of 50 Lake Shore Drive's driveway, which has been used only for access to 50 Lake Shore Drive and has never gone farther than its house (i.e., never to the pond itself). The rest was part of 50 Lake Shore Drive's side yard.

Other than the part used for 50 Lake Shore Drive's driveway, Crown Path was physically impassable by motor vehicle. Crown Path was heavily wooded from Lake Shore Drive through its hairpin turn, and it contained shrubbery and trees toward the water. This shrubbery and trees within Crown Path made vehicular travel over it impossible. Various other obstructions in Crown Path also prevented passage over it, including a concrete block retaining wall that extended approximately twenty-six feet over it, and portions of two chain link fences one an approximately six-foot section of fencing near the garage on 50 Lake Shore Drive, and the other an approximately ten-foot section of fencing near the pond. In addition, the former owners of 54 Lake Shore Drive used Crown Path as a year-round storage area for their pontoon boat, trash barrels, a barbeque, a lawnmower, and other household goods.

At present, most of Crown Path is used as part of the plaintiffs' front lawn, and some is used as part of their driveway. [Note 13] Its entrance by Lake Shore Drive is partially blocked by a stone wall, and is blocked by the water's edge by brush and trees.

So far as the evidence showed, no one other than the owners of 50 Lake Shore Drive and 54 Lake Shore Drive has ever used Crown Path for access to the water and, prior to the filing of this case, only defendant Gary Lingley had ever asserted a right to do so. [Note 14] As the town stipulated, there was no evidence of anyone, town employees included, having ever used Crown Path to access the pond. And, prior to this action, the town never requested anyone to remove obstacles within Crown Path or demanded that Crown Path be open for its benefit.

In short, Crown Path has never been used as a right of way to the water, by anyone, at any time. [Note 15]

Further relevant facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

The town's claimed right of access over the Crown Path area is based solely on the 1914 Plan's depiction of Crown Path and the references in some of its source deeds to those lots' right to use the subdivision's roads. The plaintiffs contend that, to the extent the town ever had an easement over Crown Path (an issue I need not, and do not, decide), all such rights have been abandoned. The plaintiffs are correct that abandonment has occurred.

"[A]bandonment of an easement is a question of intention to be ascertained from the surrounding circumstances and the conduct of the parties." Carlson v. Fontanella, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158 (2009) (citing Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 592 (1965)). Nonuse by itself does not prove abandonment, see Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 528 n.15 (2012), but it is a factor, when combined with others, from which abandonment can be inferred. See Sindler, 348 Mass. at 592-593 ("[F]or a period of over thirty-five years, the respondent . . . permitted the occurrence of events and relatively permanent changes in the disputed area, all of which combine to warrant an inference that it has abandoned its rights to the easement in question."); Lund v. Cox, 281 Mass. 484 , 492-493 (1933) ("Physical obstructions on the servient tenement, rendering user of the easement impossible and sufficient in themselves to explain the nonuser, combined with the great length of time during which no objection has been made to their continuance nor effort made to remove them, are sufficient to raise the presumption that the right has been abandoned and has now ceased to exist."); Carlson, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 158-160. See also Siebecker v. Orefice, 22 LCR 178 , 181-182, 2014 WL 1896414 at *6 (2014) (Land Ct.) aff'd, 87 Mass. App. Ct. 1126 , 2015 WL 3477162 (June 3, 2015) (Mem. and Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) ("[A]bandonment may be found based on a totality of three elements: (1) long-term nonuse, (2) acquiescence by the dominant estate to obstruction of the easement, [and] (3) inconsistent use by the dominant estate."). In particular, nonuse together with the "failure to protest acts which are inconsistent with the existence of an easement, particularly where one has knowledge of the right to use the easement, permits an inference of abandonment." Carlson, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 158. See Sindler, 348 Mass. at 593; Lund, 281 Mass. at 492-493.

Here, the town has never used Crown Path, nor, until this lawsuit, asserted a right to do so. Instead, for decades, it acquiesced to the inconsistent uses that area's owners were making of it. Prior to intervening in this action, the town never protested the many obstacles vegetation, chain link fences, a concrete retaining wall, trash barrels, a barbeque, a lawnmower, a pontoon boat, etc. in Crown Path that prevented vehicular access over it. Nor did the town object to the plaintiff's extensive landscaping work in the Crown Path area until this lawsuit.

The town had knowledge of Crown Path through its depiction on the 1914 Plan, knowledge through decades of observation of its use by the plaintiffs in ways inconsistent with its use for access to the pond, knowledge of the practical and physical impediments to using it for access to the water, and has always used alternative routes to access the pond. All this, combined with the town's long period of non-use, is sufficient to permit an inference of abandonment. I do so, and find that the town has abandoned whatever easement rights it has over Crown Path. [Note 16]

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the town has abandoned all rights of easement over Crown Path and so declare. Final judgment shall also now enter against defendant J.M.J. Realty Trust, declaring that it has no easement rights to use Crown Path, based on its failure to timely respond to the plaintiffs' interrogatories without good cause, Mass. R. Civ. P. 33(a)(3), (4) and (6), and its failure, again without good cause, to have counsel enter an appearance on its behalf by the court-ordered deadline of March 26, 2015. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The plaintiffs' property, for example, is a combination over a dozen lots (lots 301-313, and half of 300), and the entirety of Crown Path.

[Note 2] A paper street is "a street shown on a plan but not built on the ground." Berg v. Town of Lexington, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 569 , 570 (2007).

[Note 3] The J.M.J. Realty Trust, which owns a house lot over 1,000 feet away, was defaulted on two independent grounds. The first a default and associated order pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 33(a)(3), (4) and (6) for failure to respond to the plaintiffs' interrogatories without good cause occurred while the Trust was represented by counsel. See Docket Entries (Oct. 17, 2014; Oct. 20, 2014; Nov. 20, 2014); Institution for Sav. in Newburyport & its Vicinity v. Langis, 92 Mass. App. Ct. 815 (2018). Because a trust must have counsel and cannot be represented by its trustees pro se, its then-counsel's motion to withdraw (he was not being paid) was repeatedly denied while the Rule 33(a) motion, along with the Trust's failure to respond to other discovery, were still pending. See Docket Entries (Jul. 9, 2014; Aug. 13, 2014) and the case law cited therein. When the attorney's motion to withdraw was ultimately allowed after default was entered, the Trust was directed to have successor counsel file an appearance within thirty days. See Docket Entry (Jan. 6, 2015).

The attorney who subsequently entered an appearance on behalf of the Trust was disqualified because of a conflict, and no successor counsel filed an appearance by the court-ordered deadline of March 26, 2015. See Docket Entries (Feb. 6, 2015; Feb. 24, 2015; Mar. 12, 2015; Mar. 30, 2015). Judgment shall thus enter against the Trust on that basis as well. See id. The plaintiffs' motion for entry of a separate and final judgment against the Trust was denied solely to avoid multiple appeals in the same case, see Long v. Wickett, 50 Mass. App. Ct. 380 , 386404 (2000), and will now be entered along with a Judgment addressing the town's claims, bringing this matter to a full conclusion.

[Note 4] The town stipulated that its rights to Crown Path, if any, are based solely on its status as a landowner in the Woodland Park Subdivision as derived from the 1914 Plan and not, in any manner, on its status as a municipality.

[Note 5] The lots depicted on the 1914 Plan that are currently owned by the town are: (1) Lots 105-107, 408-409, 968-969 ("Town Parcel 1"); (2) Lots 410-417 ("Town Parcel 2"); (3) Lots 429-473 and 805-818 ("Town Parcel 3"); (4) Lots 484-493 and 504-518 ("Town Parcel 4"); (5) Lots 522-528, 539-542, 543-555, and 604-613 ("Town Parcel 5"); (6) Lots 616-619 ("Town Parcel 6"); (7) Lots 529-533 and part of Lot 800 ("Town Parcel 7"); (8) Lots 621-624 and 589-591 ("Town Parcel 8"); (9) Lots 945-947 ("Town Parcel 9"); (10) Lot 620 ("Town Parcel 10"); and (11) Lots 266-267 ("Town Parcel 11").

[Note 6] The town so stipulated. It also stipulated that it has no present plans or intention to use Crown Path.

[Note 7] The plaintiffs' property consists of part of lot 300, and lots 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312 and 313 on the 1914 Plan.

[Note 8] 50 Lake Shore Drive consists of Lots 301, 302, 303, 304, 305, 306, 307, 308, 309, and a portion of Lot 300 on the 1914 Plan.

[Note 9] 54 Lake Shore Drive consists of Lots 310, 311, 312, and 313 on the 1914 Plan.

[Note 10] The two properties legally merged in 2008 when their title came into the plaintiffs' common ownership. With the plaintiffs' subsequent improvements to the properties, they have physically appeared to be a single lot with a single residence since 2011.

[Note 11] The plaintiffs' 2006 and 2008 deeds each describe the land conveyed as bounded by Crown Path. As stipulated by the parties, the plaintiffs' source deeds from the original owner of the subdivision property also describe the properties conveyed as bounding on Crown Path, and all subsequent conveyances in the plaintiffs' chain of title contain such bounding descriptions. So far as the evidence showed, there has been no exception or reservation of the fee in Crown Path by any of the plaintiffs' predecessors in title. Thus, by acquiring title to the land abutting Crown Path, the plaintiffs also acquired the fee in Crown Path itself. See G.L. c. 183, § 58.

[Note 12] This corresponds with United States Geographical Survey maps from 1943, 1950, 1958, 1965, 1970 and 1977 that all depict the 50 Lake Shore Drive and 54 Lake Shore Drive properties as developed with residences, with none showing Crown Path as existing on the ground.

[Note 13] The plaintiffs removed the fencing and retaining wall.

[Note 14] Mr. Lingley's activities on Crown Path, which resulted in the plaintiffs' filing of this lawsuit to stop them, were not done in good faith, but rather in an attempt to get money from the plaintiffs. The J.M.J. Realty Trust property where Mr. Lingley lives is over 1,000 feet away from Crown Path and uses a well-developed, much closer, direct access route to Dudley Pond (Maiden Lane) when its residents actually want to go to the pond. Here, on a dozen occasions in provocative fashion, Mr. Lingley drove onto the Crown Path land (the plaintiffs' yard) and simply parked there on the grass, doing nothing further, with no attempt to get to or use the pond. When challenged by the plaintiffs, he said he would continue doing this until paid to stop, and referred the plaintiffs to his then-attorney to negotiate an amount he would accept. The plaintiffs declined to pay him, and instead filed this lawsuit. See Docket Entry (Aug. 13, 2014).

[Note 15] Because of the various impediments to using Crown Path, it is not surprising that it has never been used as a right of way. As discussed, the physical obstructions historically located throughout Crown Path rendered it impassable by vehicle. Even without those obstructions, it would be impracticable to use Crown Path as an access route to the pond. Crown Path does not conform to current subdivision dimensional regulations, and navigating vehicles over it would be difficult because of its hairpin turn. With its steep edge and boulders along the water, boat access would be difficult, if not impossible. It is also highly doubtful that the conservation commission would grant approval for the construction of a roadway to the water.

[Note 16] The town argues that it could not lawfully abandon its alleged easement in Crown Path without following the voting and other requirements of G.L. c. 40, § 15. I disagree. G. L. c. 40, § 15 concerns only land taken by eminent domain, see Muir v. City of Leominster, 2 Mass. App. Ct. 587 , 593 (1974), and is thus immaterial to this case because the town's claimed right of way over Crown Path is based solely on alleged grants of easement for properties the town acquired by deed. See Transcript (Closing Arguments) at 9-12; Intervenor's Post-Trial Brief at 11.

JOHN MOSS and AMY BORNER v. GARY LINGLEY and ANNMARIE LINGLEY as Trustees of the J.M.J. Realty Trust and TOWN OF WAYLAND, acting by and through its BOARD OF SELECTMEN, BOARD OF PUBLIC WORKS and CONSERVATION COMMISSION.

JOHN MOSS and AMY BORNER v. GARY LINGLEY and ANNMARIE LINGLEY as Trustees of the J.M.J. Realty Trust and TOWN OF WAYLAND, acting by and through its BOARD OF SELECTMEN, BOARD OF PUBLIC WORKS and CONSERVATION COMMISSION.