Introduction

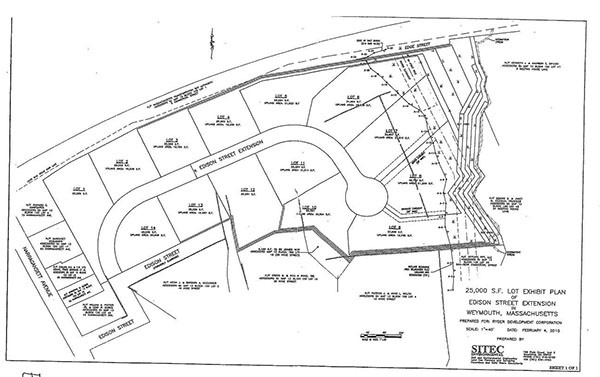

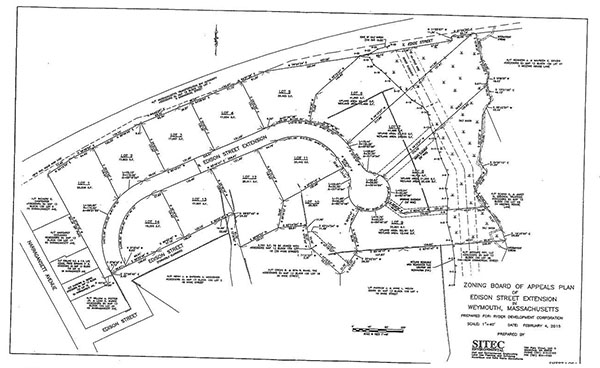

Defendants Kenneth Ryder and his company, Ryder Development Corporation, propose to subdivide approximately nine acres of woodland (the "Ryder Property") in Weymouth's Idlewell neighborhood into fourteen single-family residential lots. It is possible to subdivide the Ryder Property into fourteen lots that each conform to the applicable minimum lot area requirement under Weymouth's Zoning Ordinance, and Mr. Ryder has a subdivision plan that does so. See Ex. 1. The lots on that plan, however, are awkwardly shaped with many of them needing "pigtails" to have sufficient area. Mr. Ryder thus prefers an alternative plan, which has more compact lots. See Ex. 2. The problem with that alternative, however, is that many of the lots will now be undersized.

Mr. Ryder thus applied to Weymouth's Board of Zoning Appeals (the "Board" ) [Note 1] for a special permit pursuant to Article XV, § 120-53 of the Zoning Ordinance, under which the minimum lot area may be reduced for lots that satisfy all of its requirements. One of those requirements is that the lot from which the subdivision is made must have existed in its current configuration prior to December 1, 2013. The Ryder Property, which was five separate lots as of that date and only subsequently combined into one, does not satisfy this requirement. Moreover, a portion of one of those lots has since been conveyed out, so that the Ryder Property is not even in the same configuration as the five when combined. Despite this, the Board granted Mr. Ryder's special permit application.

This action is a G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal from the Board's decision. The plaintiffs, Christine Berns and Joseph Santos, are abutters to the Ryder Property and contend that the Board's decision should be reversed because the requirements for the special permit have not been met. Mr. Ryder argues that he has met those requirements and, in any event, contends that the plaintiffs lack standing to challenge the Board's decision.

This case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and documents admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully explained below, I find and rule that the plaintiffs have standing and Ryder has not satisfied the special permit provisions of the Zoning Ordinance. The Board's decision is thus reversed and vacated.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

Applicable Provisions of Weymouth's Zoning Ordinance

The Ryder Property is located in Weymouth's R-I zoning district, which has a minimum lot area requirement of 25,000 square feet. See Zoning Ordinance, Article XV, § 120-51; Zoning Ordinance, Table 1, Schedule of District Regulations. There are certain circumstances, however, under which the Board may allow smaller lots by special permit. These circumstances are set forth in Article XV, § 120-53 and Article XXV, § 120-122(D) of the Zoning Ordinance.

Article XV, § 120-53 provides:

EXCEPTIONS BY BOARD OF ZONING APPEALS

If the average size or area of residential lots in the surrounding neighborhood is nonconforming with respect to lot area and the new lots to be created are larger or of a similar area as the surrounding lots, the Board of Zoning Appeals may consider granting a special permit if all of the following requirements have been met. . . :

A. A lot [Note 2] shall be in existence in its current configuration prior to December 1, 2013.

B. The lot to be subdivided shall be at least 40,000 square feet.

C. The proposed new lots shall meet frontage requirements.

D. The proposed new lots shall not be less than 17,500 square feet in area.

E. The Board of Zoning Appeals shall make a finding that the proposed lots are of a similar lot size configuration to lots in the surrounding neighborhood.

or take any other action in relation thereto.

Zoning Ordinance, Article XV, § 120-53 (emphasis added).

If those requirements are satisfied, the Board then moves on to the special permit provisions of Article XXV, § 120-122(D), which states:

SPECIAL PERMITS

* * *

The special permit granting authority may approve any such application for a special permit only if it finds that, in its judgment, all of the following conditions are met:

(1) The specific site is an appropriate location for such a use.

(2) The use involved will not be detrimental to the established or future character of the neighborhood or town.

(3) There will be no nuisance or serious hazard to vehicles or pedestrians.

(4) Adequate and appropriate facilities will be provided for the proper operation of the proposed use.

(5) The public convenience and welfare will be substantially served.

Zoning Ordinance, Article XXV, § 120-122(D).

The Proposed Subdivision

Mr. Ryder's company, defendant Ryder Development Corp., [Note 3] is the current owner of the Ryder Property, which is an approximately nine acre parcel of unimproved woodland located between the MBTA's Greenbush commuter rail line and Commercial Avenue, one of Weymouth's main streets. Ryder proposes to subdivide the Ryder Property into fourteen singlefamily lots. The sole access to or from the subdivision is via Edison Street, which is presently a dead-end private way with two houses on it. Edison Street intersects with Narragansett Avenue, which connects with Commercial Avenue to the south and extends north toward the residences beyond the MBTA train tracks. The neighborhood consists mostly of older homes on small lots under 15,000 square feet in area.

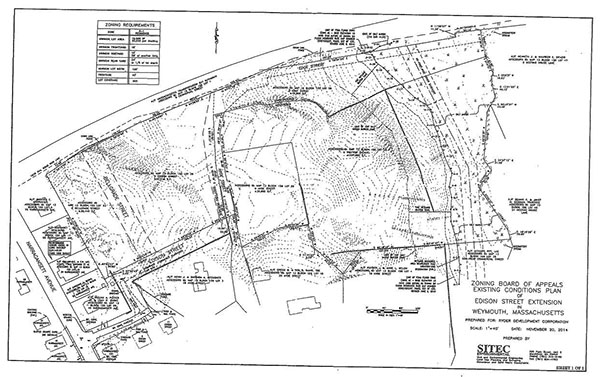

The Ryder Property is shown on the Zoning Board of Appeals Existing Conditions Plan of Edison Street Extension dated November 20, 2014, a copy of which is attached as Ex. 3. As that plan shows, the Ryder Property was previously five separate lots. [Note 4] When this action commenced on July 9, 2015, former defendant Kevin Rains, as Trustee of the Belgrade Nominee Trust, owned a portion of the Ryder Property and former defendants Gregg and Rita Rains together owned the remainder. [Note 5] Ryder acquired title to the Rains' and the Trust's respective portions of the Ryder Property during the pendency of this action. [Note 6] In 2015, an approximately 3,701-square-foot portion of one of the lots that is now part of the Ryder Property was carved out and conveyed to Gregg and Rita Rains to be joined with their yard next door.

Ryder has two different plans for the Ryder Property that both lay out fourteen lots on a proposed arc-shaped cul-de-sac that intersects with Edison Street's existing dead-end. The layouts on those two plans are essentially the same, except as follows.

On one of the plans, the "25,000 S.F. Lot Exhibit Plan of Edison Street Extension in Weymouth, Massachusetts" dated February 4, 2015 (the "Pigtails Plan"), a copy of which is attached as Ex. 1, ten of the fourteen lots have a "pigtail" - a narrow strip of land that extends behind other lots in the subdivision and adjacent to the "pigtails" of the other lots. [Note 7] With the "pigtails," the area of each of the fourteen lots satisfies the R-1 zoning district's 25,000-squarefoot minimum lot area requirement.

On the other plan, the "Zoning Board of Appeals Plan of Edison Street Extension in Weymouth, Massachusetts" dated February 4, 2015 (the "Board Plan"), a copy of which is attached as Ex. 2, none of the lots has a "pigtail." Eight of the fourteen lots satisfy the 25,000- square-foot minimum lot area requirement. Each of the other six lots is under 25,000 square feet in area, but over the 17,500-square-foot minimum required for a special permit under § 120-53. [Note 8]

Ryder's preference is to subdivide the Ryder Property into lots without "pigtails" as depicted on the Board Plan. Because six of the lots on that plan do not satisfy the minimum lot area requirement, zoning relief from the Board is required to do so. [Note 9]

The Special Permit

On March 3, 2015, pursuant to Article XV, § 120-53 and Article XXV, § 120-122(D) of the Zoning Ordinance, Ryder applied to the Board for a special permit to subdivide the Ryder Property as shown on the Board Plan (Ex. 2), with six of the proposed lots under 25,000 square feet. After public hearing, the Board granted Ryder's special permit application by decision filed with the town clerk's office on June 22, 2015. In its decision, the Board found:

All criteria were met for the Special Permit and the standards of Section 120.53 were met due to the following reasons:

1. The lot layout was better by eliminating the pigtail lots.

2. The more compact lot made it less complicated for liability, insurance, and survey work.

3. These lots meet or exceed the standard lot size of the neighborhood.

4. The reduction in lot size for six lots does not increase the potential density of the neighborhood.

Special Permit Decision (Jun. 22, 2015).

This case is the plaintiffs' appeal of the Board's decision.

The Plaintiffs' Properties

The plaintiffs each live next to the Ryder Property.

The backyard of Ms. Berns' home at 55 Narragansett Avenue directly abuts the Ryder Property near the proposed entrance to the subdivision off of Edison Street's existing dead-end. She currently maintains a garden and stone wall in that area.

Mr. Santos' home at 11 Edison Street is located at Edison Street's existing dead-end. He bought his house because of its quiet location on the dead-end and lives there with his wife and young children. Like others in the neighborhood, Mr. Santos spends time in the woods where Ryder's proposed subdivision will be built. Neighborhood children often play in those woods and on Edison Street as well.

Edison Street, because it is presently a dead-end, currently has relatively little traffic. Its current travel width is approximately ten to fourteen feet wide, making two-way traffic difficult. At present, because it is a dead-end, trash collectors typically back down the street to use it. It is similarly awkward for emergency vehicles.

Narragansett Avenue, particularly the part near the plaintiffs' houses, has heavy traffic at certain times of the day. This sometimes leads to congestion when school buses stop at its intersection with Commercial Street. Mr. Santos and Ms. Berns claim that this causes them delay when turning onto Narragansett Avenue at these times.

Ms. Berns and Mr. Santos contend that Ryder's proposed subdivision will exacerbate their ongoing traffic problems. However, they offered no expert testimony to support this. They also claim that because Edison Street is so narrow, using it for access to the subdivision will be dangerous - in patiicular, that vehicles will have difficulty navigating the proposed ninety-degree turn where the subdivision's cul-de-sac would intersect with Edison's existing dead-end. The degree to which there will be such difficulty, however, and its actual effect on the plaintiffs, is unknown since they offered no traffic studies or other expert testimony to support their claims. Importantly, however, neither did Ryder to rebut them.

Further relevant facts are set fmih in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

The plaintiffs contend that the Board's decision granting the special permit should be reversed because the requirements for a special permit under the Zoning Ordinance have not been met. Ryder argues that the plaintiffs lack standing to challenge the Board's decision and further contends that the Board acted within its allowable discretion in granting the special permit. As more fully discussed below, I find that the plaintiffs have standing and the requirements for the special permit have not been satisfied.

Standing

Only a "person aggrieved" has standing to challenge a municipal zoning board's decision. G.L. c. 40A, § 17. See 81 Spooner Rd., LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012). To be "aggrieved" within meaning of G.L. c. 40A, § 17, one "must assert 'a plausible claim of a definite violation of a private right, a private property interest, or a private legal interest."' Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 120 (2011) (quoting Harvard Sq. Defense Fund, Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Cambridge, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 491 , 493 (1989)). More particularly, one must suffer an infringement of a "specific interest that the applicable zoning statute, ordinance, or bylaw at issue is intended to protect." Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 30 (2006). "Aggrievement requires a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm." Kenner, 459 Mass. at 121. "The injury must be more than speculative," Marashlian v. Zoning Ed. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996), and must be "special and different from the injury the action will cause the community at large." Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005). However, "the term 'person aggrieved' should not be read narrowly." Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721.

Direct abutters, such as each of the plaintiffs, enjoy a rebuttable presumption that they are persons "aggrieved." [Note 10] 81 Spooner Rd., LLC, 461 Mass. at 700. Ryder can rebut the plaintiffs' presumption by showing that their "claims of aggrievement are not within the interests protected by the applicable zoning scheme." Picard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Westminster, 474 Mass. 570 , 573-574 (2016). See 81 Spooner Rd., LLC, 461 Mass. at 702. If the plaintiffs allege harm to a protected interest, Ryder can rebut the presumption by producing credible evidence that refutes the presumed fact of aggrievement. See 81 Spooner Rd., LLC, 461 Mass. at 702. This can be done by presenting evidence showing the alleged aggrievement is either "unfounded or de minimus." Id.

If Ryder successfully rebuts the presumption, the court must decide the issue of standing "on the basis of all the evidence." Id. at 701. The plaintiffs must then prove standing "by putting forth credible evidence to substantiate the allegations." Id.

"Credible evidence" has both quantitative and qualitative components. See Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441.

Quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made. Qualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the board's action. Conjecture, personal opinion, and hypothesis are therefore insufficient.

Id. (internal citations omitted).

Ryder contends that the plaintiffs do not have standing because they have not proven that they will suffer any particularized injury or that the reductions in lot area allowed by the special permit will cause them harm. However, because the plaintiffs benefit from the presumption of aggrievement, and because their alleged harm of traffic impacts is within the scope of the interests protected under the zoning laws, see Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 722; Weymouth Zoning Ordinance, Article I, § 120-2(A) (purposes of Wayland Zoning Ordinance include "lessen[ing] congestion in the streets" and "facilitate[ing] the adequate provision of transportation"), Ryder was required to come forward with credible affirmative evidence refuting that presumption. See 81 Spooner Rd., LLC, 461 Mass. at 702. Simply put, Ryder did not do so. [Note 11]

At present, Edison Street is narrow, cannot easily accommodate two-way traffic, and is difficult for emergency vehicles, trash collectors, and snow plows to use. Because of the traffic congestion on Narragansett Avenue, driving to and from Edison Street is challenging at certain times of day. Given this, the plaintiffs' claim that using Edison Street for access to the new lots allowed by the special permit will be problematic is sufficient to require Ryder to rebut it. Because their presumed standing is based on traffic impacts, Ryder's rebuttal must be supported by expert evidence, and no such evidence was presented. [Note 12] Because the sole access to Ryder's proposed subdivision will be off of Edison Street's dead-end, directly in front of Mr. Santos' home and behind Ms. Berns', their claimed aggrievement is particularized to their respective properties compared to neighborhood at large.

The plaintiffs have thus asserted a particularized injury to a protected interest that warrants the presumption of aggrievement. Ryder has not come forward with credible evidence to rebut it.

The Merits

The plaintiffs contend that the Board erred in granting the special permit because the requirements for a special permit under Article XV, § 120-53 and Article XXV, § 120-122(D) of the Zoning Ordinance have not been met. Ryder disagrees and argues that the Board's decision was reasonable and within its allowable discretion, particularly because the proposed subdivision will have the same density whether or not it has the reduced lot areas.

As Ryder argues, the Board Plan (with the reduced lot areas approved by the Board) and the Pigtails Plan (with all full-size lots allowed by right) both lay out fourteen lots and the homes on them will be the same, giving the two plans the same density. But this is not enough. To affirm the Board's decision, I must find that all of the Zoning Ordinance's requirements for the special permit have been met. See Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 n.5 (2003). As more fully discussed below, they have not.

The Standard of Review

In this G. L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal, as in all such proceedings, the reviewing court makes de novo factual findings based solely on the evidence admitted in court, and then, based on those facts, determines the legal validity of the municipal body's decision, with no evidentiary weight given to any findings by the Board. See Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y, Inc. v. Board of Appeal of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381-382 (2009).

The Board's decision "'cannot be disturbed unless it is based on a legally untenable ground' or is based on an 'unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary' exercise of its judgment in applying land use regulation to the facts as found by the judge." Id. at 381-382 (quoting Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 487 (1999)). In determining whether the Board's decision was "based on 'a legally untenable ground,"' the court must determine whether it was decided "on a standard, criterion, or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws." Britton, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73. In determining whether the decision was "unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary," "the question for the court is whether, on the facts the judge has found, any rational board" could come to the same conclusion. See id. at 74.

Where, as here, the grant of a special permit is at issue:

not only must [the special permit granting authority] make an affirmative finding as to the existence of each condition of the statute or by-law required for the granting of the . . . special permit . . . but the judge in order to affirm the board's decision on appeal must find independently that each of those conditions is met.

Id. at 73 n.5 (quoting Vazza Properties, Inc. v. City Council of Woburn, l Mass. App. Ct. 308, 311 (1973)).

The Requirements for a Special Permit Have Not Been Met

The validity of Ryder's special permit turns on Article XV, § 120-53 and Article XXV, § 120-122(D) of the Zoning Ordinance. The interpretation of a zoning ordinance is a question of law for the court, governed by the familiar principles of statutory construction. See Doherty v. Planning Bd. of Scituate, 467 Mass. 560 , 567 (2014). The court first looks to the ordinance's language, and, if its meaning is plain and unambiguous, the plain wording shall be enforced unless doing so would '"yield an absurd or unworkable result."' Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership v. Board of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 477 (2012) (quoting Adoption of Daisy, 460 Mass. 72 , 76 (2011)). Where an ordinance does not define its words, the court "give[s] them their usual and accepted meanings, as long as these meanings are consistent with the statutory purpose . . . [and] derive[s] the words' usual and accepted meanings from sources presumably known to the statute's enactors, such as their use in other legal contexts and dictionary definitions." Doherty, 467 Mass. at 569 (internal citations and quotations omitted). The court's objective is "to give effect 'to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous."' Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership, 461 Mass. at 477 (quoting Connors v. Annino, 460 Mass. 790 , 796 (2011)).

Article XV, § 120-53

Article XV, § 120-53 of the Zoning Ordinance provides that the Board may grant a special permit under that section only "if all of the following requirements have been met." Zoning Ordinance, Article XV, § 120-53 (emphasis added). Section 120-53 then sets forth five requirements, one of which is that "[a] lot shall be in existence in its current configuration prior to December 1, 2013." Zoning Ordinance, Article XV, § 120-53(A). The Zoning Ordinance defines the word "lot" as "[a] parcel of land in single, joint or multiple ownership, whether or not plotted, and not divided by a public street." Zoning Ordinance, Article II, § 120-6. The word "configuration" is undefined in the Zoning Ordinance. In the dictionary, "configuration" is defined as "[t]he arrangement of the parts or elements of something" and "[t]he form of a figure as determined by the arrangement of its parts; outline; contour." The American Heritage Dictionary 308 (Second College Edition 1991).

Based on the foregoing, it is plain and unambiguous that for property to qualify for a special permit under Article XV, § 120-53, that property must be a parcel of land that is presently arranged the same as it was before December 1, 2013. That requirement is not met in this case.

The Ryder Property presently consists of approximately nine acres of land that came into its current arrangement only in 2015, after Ryder acquired multiple parcels of land and combined them into one. As Ryder admitted, before he acquired title to the Ryder Property, the underlying land consisted of five separate lots. See Answer at 3, ¶ 19 (Jul. 22, 2015). The lots had different owners, different addresses, and different assessor's identification numbers. The distinct nature of each lot is further shown by Ryder's 2014 Existing Conditions Plan of the Ryder Property, which depicts the Ryder Property as five separate parcels, each with its own square footage. See Ex. 3.

In addition, in 2015, an approximately 3,701-square-foot portion of one of the lots that now comprises the Ryder Property was carved out for Gregg and Rita Rains and is not part of the proposed subdivision. Thus, even if the five lots could be considered one, they still fail the test that they have the same configuration as existed prior to December 1, 2013.

For those reasons, the Ryder Property is not presently in the same configuration as before December 1, 2013, nor was it so at the time of the Board's decision. It thus does not satisfy the requirements of Atiicle XV, § 120-53.

Article XXV, § 120-122(D)

Under Article XXV, § l 20- l 22(D), the special permit granting authority may grant a special permit "only if it finds that, in its judgment, all of the . . . conditions [enumerated in that section] are met." Zoning Ordinance, Article XXV, § 120-122(D). This provision clearly and

unambiguously provides that for a special permit to issue, the special permit granting authority (here, the Board) must find that all of the conditions of Article XXV, § 120-122(D) have been satisfied.

Based on the evidence before me, I am unable to find that all of those conditions have been met. In particular, the evidence does not show that "[t]here will be no nuisance or serious hazard to vehicles or pedestrians," Zoning Ordinance, Article XXV, § 120-122(D)(3), or that "[a]dequate and appropriate facilities will be provided for the proper operation of the proposed use." Zoning Ordinance, Article XXV, § 120- l 22(D)(4). As the permit holder, once the plaintiffs' standing was established, Ryder had the burden of making that showing. That burden was not met.

Ryder argues that the Board's decision is nonetheless reasonable because the planning board will consider issues similar to those under Article XXV, § 120-122(D) in connection with its subdivision review of the proposed project. That argument is wrong. The planning board's consideration of similar issues in the different context of its subdivision review does not obviate the requirement that the Board find that all of the conditions of Article XXV, § 120-122(D) are met.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Board's decision granting the special permit is reversed and vacated.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

In his Answer, Ryder admitted to the plaintiffs' allegation that "The Subject Property consists of five (5) separate lots that collectively consist of approximately 390,000 square feet of undeveloped land." See Answer at 3, ¶ 19 (Jul. 22, 2015). Ryder is bound by that admission. See G.L. c. 231, § 87.

CHRISTINE BERNS and JOSEPH SANTOS v. RICHARD McLEOD, EDWARD FOLEY, CHARLES GOLDEN, JONATHAN MORIARTY, ROBERT STEVENS, KEMAL DENIZKURT, BRAD VINTON, BRANDON DIEM and ROBIN MOROZ as members of the Town of Weymouth Board of Zoning Appeals, KENNETH RYDER, and RYDER DEVELOPMENT CORP.

CHRISTINE BERNS and JOSEPH SANTOS v. RICHARD McLEOD, EDWARD FOLEY, CHARLES GOLDEN, JONATHAN MORIARTY, ROBERT STEVENS, KEMAL DENIZKURT, BRAD VINTON, BRANDON DIEM and ROBIN MOROZ as members of the Town of Weymouth Board of Zoning Appeals, KENNETH RYDER, and RYDER DEVELOPMENT CORP.