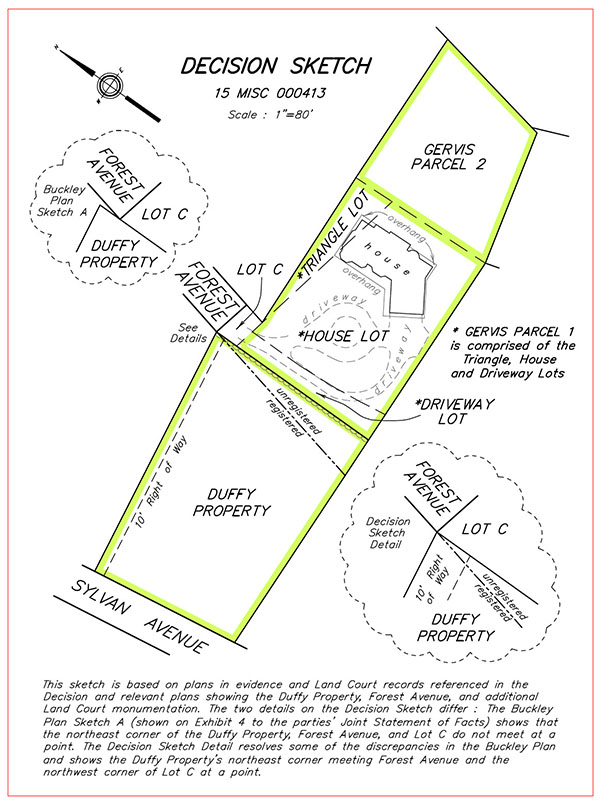

At issue in this case is whether Defendants Robert M. Gervis and Laurie L. Gervis (Defendants or Gervis) may use for access a right-of-way easement (Right of Way) located on property owned by Plaintiff Arthur X. Duffy, as Trustee of Sylvan Avenue Realty Trust (Plaintiff or Duffy). The parties own adjacent residential properties in West Newton. Duffy's property comprises both registered and recorded land, over which the Right of Way crosses. Plaintiff contends that his property is not subject to any rights in favor of Defendants because the burden of the Right of Way does not appear on his certificate of title. The property owned by the Gervises comprises several parcels of land which are shown on the attached Sketch, along with the Duffy Property, for reference.

The case came before the court on cross-motions for summary judgment. The summary judgment record includes affidavits of Michael J. Coutu, a landscape architect; Robert Buckley, a registered land surveyor; Jason Rosenberg, Esq.; and Edward Rainen, Esq., a title attorney, on behalf of Plaintiffs, [Note 1] and an affidavit of Defendant Robert M. Gervis on behalf of Defendants. [Note 2]

Based on the summary judgment record, with respect to the Right of Way, this court determines the following: (1) Defendants' rights in and over the Right of Way on the registered portion of the Duffy Property derive only from their ownership of the Triangle Lot and the Driveway Lot, two of the Lots comprising the Gervis Parcel 1. Therefore, Defendants' rights to use the Right of Way are limited to use by them in connection only with those two Lots, as they existed as of December 28, 1916; (2) Defendants, as owners of the House Lot (the third lot comprising Gervis Parcel 1), and Gervis Parcel 2 do not have appurtenant rights in and over the Right of Way on the registered portion of the Duffy property appurtenant to either the House Lot or Gervis Parcel 2; and (3) Defendants' use of the Right of Way to benefit either the House Lot or Gervis Parcel 2 impermissibly overloads the Right of Way as a matter of law. Plaintiff also sought a declaration regarding the location of a stone wall along the boundary line between the parties. With respect to that issue, the record establishes that the stone wall is located on Plaintiff's property.

The following material facts are established by the record and are not in dispute.

Gervis Property Gervis Parcels 1 & 2

1. Defendants are the owners of real property known as and numbered 204 Forest Avenue in West Newton (Gervis Property), by deed dated June 11, 1998, recorded with the Middlesex South Registry of Deeds in Book 28698, at Page 521. [Note 3] At various times in the past, the Gervis Property has been known as and numbered 200 Forest Avenue.

2. The Gervis Property comprises two recorded land parcels, shown as Lot B on a plan titled "Plan of Land in West Newton," (West Newton Plan) recorded in Plan Book 300, Plan 5 (Gervis Parcel 1), and Lot A on Plan 57 of 1955 (Gervis Parcel 2). [Note 4]

3. Charles E. Gibson, through various deeds, acquired property on the east side of Forest Avenue (or Street) that later became Gervis Parcel 1. Gervis Parcel 1 consists of three subparcels: referred to by the parties as the House Lot, the Triangle Lot and the Driveway Lot. The surveyed locations of these subparcels, in relation to the historic parcels comprising the Gervis Property, are shown on the plan attached as Exhibit C to the Supplemental Affidavit of Robert J. Buckley, RLS and Exhibit 4 to the parties' joint statement of facts (Buckley Plan). [Note 5]

a. On or about April 27, 1909, Gorman D. Gilman and Adelaide L. Gilman conveyed a parcel of land known as Lot No. 35, as shown on a "Plan of Lands on Sylvan Heights, Newton, belonging to John Coe, Willard Sears and others," recorded in Plan Book 3A, Plan 47 (Sylvan Heights Plan), to Charles E. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 3446, at Page 172.

b. On or about April 23, 1910, John Read, et al., the residuary devisees under a will of Elizabeth T. Eldredge, conveyed a parcel of land shown as Lot 36 on the Sylvan Heights Plan, to Charles E. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 3524, at Page 223-224.

c. On or about November 2, 1916, Frank J. Hale conveyed a parcel of land known as Lot A on a plan titled "Plan of Land in West Newton, Mass.," dated November 2, 1916, by E. S. Smilie, Surveyor, recorded in Plan Book 254, Plan 17 (Smilie Plan), to Charles E. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 4093, at Page 565.

House Lot

4. On or about November 1, 1913, Charles E. Gibson conveyed a parcel of land with the buildings thereon (House Lot), as shown on a plan titled "Plan of Land in West Newton Belonging to Charles E. Gibson," drawn by E. S. Smilie, Surveyor, dated October 28, 1913, recorded at the End of Book 3844 (Gibson Plan), to Stewart K. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 3844, at Page 19.

5. On or about December 31, 1913, Stewart K. Gibson conveyed the House Lot to Helen K. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 3860, at Page 81 (outlined in light green on the Buckley Plan).

6. Helen K. Gibson was the owner of the House Lot on December 28, 1916.

Triangle Lot

7. The Triangle Lot is not shown as a separate parcel on any plan of record. It is included in the deed of Lot A on the Smilie Plan. This land was acquired by Charles E. Gibson from Frank J. Hale on or about November 2, 1916, by deed recorded in Book 4093, at Page

565. The accurate surveyed layout of the Triangle Lot is shown on the Buckley Plan (outlined in orange thereon).

8. Charles E. Gibson was the owner of the Triangle Lot on December 28, 1916.

9. The Triangle Lot was first described as a distinct parcel on or about November 22, 1921, when Charles E. Gibson deeded it, together with the Driveway Lot (discussed below), to James W. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 4488, at Page 534, in which it was described as "that Triangular parcel." This deed was not recorded until January18, 1922.

Driveway Lot

10. There is no recorded plan that shows the Driveway Lot. It is located in a portion of the area labeled "Driveway" on a plan of land titled "Plan of Land in West Newton, Mass. Belonging to Charles E. Gibson," recorded in Plan Book 255, Plan 29. The accurate surveyed layout of the Driveway Lot is shown on the Buckley Plan, outlined in pink.

11. Charles E. Gibson was the owner of the Driveway Lot on December 28, 1916.

12. As noted above, in paragraph 9, Charles E. Gibson conveyed both the Driveway Lot, described as the land "between land of said Robert W. Newell, and the land of said Helen K. Gibson," and the Triangle Lot to James W. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 4488, at Page 534.

House Lot, Triangle Lot and Driveway Lot

13. After acquiring the Driveway Lot and the Triangle Lot, and recording his deed from Charles E. Gibson on January 18, 1922, James W. Gibson immediately conveyed both Lots to Helen K. Gibson by deed dated January 11, 1922, recorded in Book 4488, one page later, at Page 535.

14. On or about May 29, 1925, Helen K. Gibson conveyed the House Lot, along with the Triangle Lot and Driveway Lot, to James W. Gibson by deed recorded in Book 5420, at Page 491. The land conveyed is shown as Lot B on the West Newton Plan.

Gervis Parcel 2

15. Gervis Parcel 2 is shown as "Lot A 20370 sf" on Plan No. 57 of 1955, recorded with the accompanying deed in Book 8394, at Page 120. The plan is titled "Plan of Land in Newton, Mass."

16. Charles E. Gibson did not own Gervis Parcel 2 on December 28, 1916.

17. On or about March 22, 1945, Frank J. Hale conveyed land containing Gervis Parcel 2 to Marjorie Hale Gardner by deed recorded in Book 6836, at Page 70.

18. By mesne conveyances Defendants became the record owners of Gervis Parcel 2 on June 11, 1998 (see paragraph 1 above.)

19. Defendants installed a swimming pool entirely within Gervis Parcel 2. A portion of the decking surrounding the Pool is located on Gervis Parcel 1. Gervis Parcel 2 also contains trees, shrubbery, landscaping, a storage shed, and a small cabana located near the pool. No part of the Gervis single-family residence (Gervis House), is located on Gervis Parcel 2. The surveyed location of the structures on the Gervis Property, including the Gervis House and swimming pool, are shown on the Buckley Plan.

Duffy Property

20. Plaintiff is the owner of real property located at 44 Sylvan Avenue in West Newton (Duffy Property), by deed dated May 21, 2012, recorded in Book 59147, at Page 548, and registered as Document No. 1601569, resulting in Certificate of Title No. 251232.

21. The Duffy Property comprises two parcels, one of which is registered land. The two parcels are shown on the Gibson Plan. The parcel of registered land is shown as Lot I on Land Court Plan 2617-H (H Plan) and is outlined in gray on the Buckley Plan. The parcel of recorded land is outlined in brown on the Buckley Plan.

22. On December 28, 1916, Plaintiff's predecessor-in-title, Charles E. Gibson conveyed the Duffy Property to Robert W. Newell by two deeds (Gibson Deeds). The first was registered as Doc. 20223 and Certificate of Title No. 7594, was issued to Newell. The second was recorded in Book 4107, at Page 404. The Gibson Deeds state rights are reserved in a Right of Way and the underground utilities for the benefit of adjacent property owned by Helen K. Gibson as follows:

a. Registered Document No. 20223 states grantor is ". . . reserving to the grantor and his heirs and assigns the right of passage on foot or in vehicles over a strip ten feet wide, being the northerly portion of the premises hereby conveyed in common with the grantor and his heirs and assigns an appurtenant to and for the benefit of the remaining land of said grantor, and also of the land owned by Helen K. Gibson adjoining said land of Hale. Also reserving to the grantor, his heirs and assigns for the benefit of his remaining land, and also the land owned as aforesaid by said Helen K. Gibson, the right in common with said grantee to use the sewer as now located in the granted premises, and also to maintain and use water and gas pipes as now located through said premises."

b. The recorded deed states grantor is "reserving to the grantor and his heirs and assigns the right of passage on foot or in vehicles over a strip ten feet wide forming the northerly portion of the premises hereby conveyed in common with the grantee and his heirs and assigns in connection with the right of passage to Sylvan Avenue, reserved in the deed to said grantee above mentioned as appurtenant to and for the benefit of the adjoining land of said grantor, and also the land now owned by Helen K. Gibson adjoining said land of Hale. Said premises are also conveyed subject to the right to maintain and use the sewer, gas and water pipes as now located upon the premises hereby conveyed." (Italics added.)

23. As of the date of the summary judgment submission, the last Certificate of Title produced by the Registry District for the registered parcel of the Duffy Property was No. 185717, and it contains the following references:

a. "[s]aid parcel is shown as [L]ot I on said plan, [the H Plan]," and

b. "the above described land is subject to the restrictions set forth in Certificate 27060, so far as the same are now in force and applicable."

24. Review of the referenced Certificate No. 27060 leads to its language "the above described land is subject to the reservations and sewer rights as contained in deed from Charles E. Gibson to Robert W. Newell, dated December 28, 1916, being Document 20223." Certificate No. 27060 also states that the land is subject to certain restrictions set forth on the Certificate.

25. One of Plaintiff's predecessors-in-title granted a water line easement to the City of Newton, by instruments dated May 10, 1994, filed as Document No. 959958, and recorded in Book 24908, at Page 179. The easement is shown as "Right of Way and Water Easement" on a plan of land entitled "Plan of Land in Newton, Mass., scale 1 in. = 20 ft., November 19, 1993, John J. Regan, Land Surveyor, Newton Highlands, Mass.," recorded with the Registry in Plan Book 1994, Plan 991. It is approximately ten feet wide and covered partially by grass and dirt. There are no structures within this right of way. [Note 6]

26. Forest Avenue, shown on the Smilie Plan, is a private way, forty feet in width.

Stone Wall

27. A stone wall located near the common boundary between the Duffy Property and the Gervis Property, on the easterly boundary of Plaintiff's property is located within property owned by Plaintiff, as shown on the Buckley Plan. [Note 7]

* * * * * *

I. Summary Judgment Standard

Summary judgment may be entered if the "pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue of material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court is to draw "all logically permissible inferences" from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203

(1991). "Summary judgment is appropriate when, 'viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.'" Regis College v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 ,

284 (2012), quoting Augat Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991). When the court is faced with cross motions, it must analyze the parties' legal positions at the summary judgment stage guided by which party has the burden on the issues before the court. Each moving party bears the burden of affirmatively demonstrating the absence of triable issues of fact and its entitlement to judgment as a matter of law on those matters for which it has the burden of proof. Lev v. Beverly EnterprisesMassachusetts, Inc., 457 Mass. 234 , 237 (2010).

II. Plaintiff's Certificate of Title Contained References That, Upon Further Investigation, Would Have Put Him on Notice of The Right of Way

a. Plaintiff's Certificate of Title Referenced a Land Court Plan

Both parties have moved for summary judgment on their respective first counts of the complaint and counterclaim, seeking declarations regarding the validity of the Right of Way purportedly reserved to benefit Defendants' parcels. Defendants, as the party claiming the benefit of an easement, bear the burden of proving its existence in and over the Duffy Property, the servient estate. Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006); Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 629 (1990).

Plaintiff takes the position that the registered portion of his property is not subject to the Right of Way because the encumbrance is not specifically mentioned in the deed into Duffy nor on his Certificate of Title issued by the Registry District. Defendants counter that, despite the absence of an express description of the Right of Way on the Duffy Certificate of Title, other facts noted on the certificate should have prompted Plaintiff to investigate further.

The Duffy Property comprises both registered and recorded land. Under G. L. c. 185, § 46 a holder of a certificate of title takes "free from all encumbrances except those noted on the certificate." For registered land to be burdened, generally the easement must be shown on the certificate of title. Hickey v. Pathways Ass'n, 472 Mass. 735 , 754 (2015), citing Commonwealth Elec. Co. v. MacCardell, 450 Mass. 48 , 50 (2007). An owner, however, may take property subject to an unregistered easement under two narrow exceptions to this general rule. First, if there are facts described on a certificate of title which would prompt a reasonable purchaser to investigate further other certificates, documents or plans in the registry system, or, second, if the purchaser has actual knowledge of a prior unregistered interest, the registered property may be encumbered by the easement. See Jackson v. Knott, 418 Mass. 704 , 71011 (1994).

Defendants claim they hold a valid easement pursuant to the first exception, under which "[i]f a plan is referred to in the certificate of title, the purchaser would be expected to review that plan." Id. When Duffy took title, the most recent transfer certificate of title for the registered

portion of the Duffy Property was Certificate No. 185717. This certificate, after setting out the metes and bounds description of the parcel, provides "[s]aid parcel is shown as Lot I on said plan, [H Plan]." The H Plan, titled "Subdivision of A¹, B & C² shown on plan filed with South Registry District of Middlesex County Land in Newton Dec. 28, 1916 E. S. Smilie, Surveyor," and referenced in fact paragraph 21, supra, depicts Lot I and the Right of Way. Further investigation of the H Plan leads to Document 20223, containing the original reservation of the Right of Way by Charles E. Gibson, and would have placed Plaintiff on notice of Defendants' rights in the Right of Way.

b. Plaintiff's Certificate of Title Also References Other Certificates of Title That Plaintiff Had a Duty to Investigate

In addition to referencing the H Plan, Certificate No. 185717 also references Certificate of Title No. 27060; "[t]he above described land is subject to the restrictions set forth in Certificate [No.] 27060, so far as the same are now in force and applicable." A review of Certificate No. 27060 informs "[t]he above described land is subject to the reservations and sewer rights as contained in deed from Charles E. Gibson to Robert W. Newell, dated December 18, 1916, being Document 20223." In Document 20223, Charles E. Gibson conveyed the registered portion of the Duffy Property to Robert W. Newell, reserving for himself and his heirs and assigns the "right of passage on foot or in vehicles over a strip ten feet wide, being the northerly portion of the premises hereby conveyed in common with the grantor and his heirs and assigns as appurtenant to and for the benefit of the remaining land of said grantor, and also of the land of Helen K. Gibson, adjoining said land of Hale." [Note 8] Defendants argue that, pursuant to Jackson, Plaintiff had an obligation to investigate the reference to Certificate No. 27060

mentioned on his certificate of title, and that reference in turn would have led him to the easement described in the original deed from Charles E. Gibson to Robert W. Newell.

Plaintiff disagrees, arguing that because Certificate No. 185717 only references restrictions in other certificates of title, as opposed to easements, he was not required toinvestigate those certificates due to the distinctions between the two types of encumbrances. A restriction on the use of land is a right to compel the person entitled to possession of the land not to use it in specific ways. Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 662 (2007), citing Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 347 (1967). An affirmative easement "creates a nonpossessory right to enter and use land in the possession of another and obligates the possessor not to interfere with the uses authorized by the easement." Patterson, 448 Mass. at 663 (citations omitted).

The court finds that distinction does not relieve Plaintiff of his obligation to investigate other certificates of title or plans with the registration system. The first Jackson exception asks "whether there were facts within the Land Court registration system available . . . at the time of. . . [purchase], which would lead [a purchaser] to discover that [the property] was subject to an encumbrance, even if that encumbrance was not listed on [the] certificate of title." Jackson, 418 Mass. at 711. Purchasers are expected to review all types of relevant documents in the land

registration system, including plans and other certificates of title, to determine both their own rights and those of others. Hickey, 471 Mass. at 758; Jackson, 418 Mass. at 712; Duddy v. Mankewich, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 62 , 62 (2009).

In Plaintiff's case, Certificate No. 185717 specifically references Certificate of Title No. 27060, and reasonable purchasers would be expected to review that certificate to determine their rights. That investigation would have led Plaintiff to Document 20223, or the deed from Charles E. Gibson to Robert Newell, and alerted him to the reservation of the Right of Way easement contained in that deed. That the certificate references a "restriction" as opposed to an easement did not relieve Plaintiff of his obligation to investigate relevant certificates of title. See, e.g., Popponesset Beach Ass'n, Inc. v. Marchillo, 39 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (1996) (stating, in dicta, that "an encumbrance may bind an owner if what the certificate of title recites in the way of prior documents, plans, restrictions, rights, and reservations would prompt a reasonable purchaser to investigate further the referenced documents" under the first Jackson exception). [Note 9]

Accordingly, this court finds and rules that Plaintiff had a duty to investigate the Certificate of Title No. 27060, as well as the plan expressly referenced in Certificate No. 185717. This would have resulted in the discovery of Document 20223, and the H Plan. The explicit reference to a plan depicting the Right of Way, combined with the general reference to a prior certificate of title, constitutes adequate reference to the easement such that it burdens the portion of Plaintiff's Property that is registered. This ruling, however, represents a pyrrhic victory for Defendants because this court concludes that the Right of Way is not appurtenant to the House Lot, which constitutes the largest portion of Gervis Parcel 1 and, importantly, the portion on which the Gervis House is located.

c. The Purported Reservation of an Easement to Benefit Helen K. Gibson's Adjacent Lot Was Ineffective Because She Was a Stranger to The Deed

As noted above, Charles E. Gibson reserved for himself and his heirs and assigns the right of passage over the Right of Way to benefit the lots he retained the Triangle Lot and the Driveway Lot. He also purported to reserve rights in the Right of Way for the benefit of adjacent land owned at the time by his wife, Helen K. Gibson. Plaintiff argues that because Helen K. Gibson did not own the land conveyed by Charles E. Gibson to Robert W. Newell in Document 20223, she was a stranger to that deed and her own land could not be benefitted by any reservations within that deed. This court agrees.

"An easement cannot be imposed by deed in favor of one who is a stranger to it." Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 172 (1946), citing Hazen v. Mathews, 184 Mass. 388 , 393 (1903). Plaintiffs argue Helen K. Gibson was a "stranger" because, although she signed the deed, she had no fee interest in the land conveyed by Charles E. Gibson to Robert W. Newell. Charles E. Gibson is the sole grantor noted on Document 20223. He attempted to reserve to his wife's land an easement over the Right of Way in that document. At the time he conveyed what is now the Duffy Property to Robert Newell, however, he had not yet granted any such rights to her. To successfully reserve rights to Helen, Charles could have granted an easement directly to her, and then conveyed the Duffy Property subject to easements benefitting both his remaining land and that of Helen. See Haverhill Sav. Bank v. Griffin, 184 Mass. 419 , 421 (1903) (invalidating a grantor's attempt to reserve to a neighboring lot rights in a sewer because no such right had been granted or prescriptively acquired by the owner of the neighboring lot).

Accordingly, the purported reservation of an easement to benefit the land of Helen K. Gibson in Document 20223 is invalid.

Although she was a stranger to the deed, Helen K. Gibson did sign it, in order to release her inchoate rights of "dower and homestead." Defendants argue that because Helen K. Gibson signed the deed, she was a party to the deed and therefore not a "stranger" unable to be benefitted by an easement. Dower rights in effect in 1916 afforded a widow a life estate in one-third of the real estate owned by her husband during their marriage. Opinion of the Justices, 337 Mass. 786 , 788 (1958). These rights vested only if the wife survived the husband. Id. at 791. [Note 10]

Defendants argue Helen's signature on the deed makes her a party to it, a status sufficient to receive and benefit from rights conveyed pursuant to the deed. This, in Defendants' view, aligns with Hodgkins, in which a grantor attempted to reserve easement rights over the conveyed property to himself as well as an adjacent party. When the adjacent party asserted those easement rights, the court ruled the adjacent land owner did not have the benefit of the easement because the adjacent party was not a party to the deed, and therefore was a stranger. Hodgkins, 323 Mass. at 172.

The language inserted in Document 20223 serves only as a release of Helen's dower rights. An inchoate right of dower is "a kind of property with incidents sui generis." Fitcher v. Griffiths, 216 Mass. 174 , 175 (1913). It is a "'valuable interest which is frequently the subject of

contract and bargain . . . . It is more than a possibility, and may well be denominated a contingent interest.'" Fitcher, 216 Mass. at 175, citing Bullard v. Briggs, 7 Pick. 533 , 538 (1829). Dower rights have been described as "a vested right of value, dependent on the contingency of survivorship," Mason v. Mason, 140 Mass. 63 , 63 (1885). Although a clear "precise technical description" is lacking, it appears to be accepted that a dower right was an "incumbrance upon land, good consideration for a promise, and is protected by the courts during coverture." Fitcher, 216 Mass. at 175 (internal citations omitted).

While dower rights may have constituted a contingent interest, a wife's signature releasing those rights in an instrument of conveyance did not appear to convey or grant title. For example, in cases where a husband attempted to convey land owned by his wife using a deed in his name only that his wife signed to release her dower right, courts held that such execution was insufficient to convey the wife's property. See Bruce v. Wood, 1 Met. 542 (1840) (stating wife's dower release was insufficient to convey her fee and that wife needed to be party to the "efficient and operative parts" of the conveyance); Greenough v. Turner, 11 Gray 332 (1858) (wife did not join in deed of conveyance of her land with only a release of homestead rights at the end); Lithgow v. Kavenagh, 9 Mass. 161 , 173 (1812) (stating that a wife's release of her

dower right in property she herself owned did not join her in conveying title and was solely to consent to the husband's conveyance of the property); Anttila v. A. E. Lyon, Co., 222 Mass. 126 , 127 (1915) (stating the release of a spouse's dower or curtsey not listed as grantor in a mortgage title was intended to operate solely as a release and the inclusion of "all other rights therein" title should be read in that context and not as conveying interest in land). In the instant matter, Helen K. Gibson did not own the Duffy Property when her husband conveyed it. As a result of this

III. The House Lot and Gervis Parcel 2 are not benefitted by the Right of Way

Plaintiff argues that Defendants are now overloading the Right of Way by using it to access after-acquired parcels. [Note 11] Charles E. Gibson only owned a small portion of what is now Gervis Parcels 1 and 2 when he reserved the Right of Way on December 28, 1916, to purportedly benefit Gervis Parcels 1 and 2. Specifically, he owned the Triangle Lot and the Driveway Lot only. By using the Right of Way to access the House Lot portion of Gervis Parcel 1, as well as the pool and pool house located on Gervis Parcel 2, Plaintiffs argue Defendants are using the Right of Way to access land it does not benefit.

After-acquired property, or property located beyond the dominant estate, can benefit from an easement only if the easement is one in gross, a personal interest in or right to use land of another, or the owner of the after-acquired property receives the consent of the owner of the servient estate. McLaughlin v. Bd. of Selectmen of Amherst, 422 Mass. 359 , 364 (1996); Murphy v. Mart Realty of Brockton, Inc., 348 Mass. 675 , 67879 (1965). Absent the express consent of the owner of the servient estate, the use of an appurtenant easement to benefit property located beyond the dominant estate constitutes an overloading of the easement. Taylor v. Martha's Vineyard Land Bank Comm'n, 475 Mass. 682 , 686 (2016), quoting Murphy, 348 Mass. at 67879; see also Southwick v. Planning Bd. of Plymouth, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 315 , 318 (2005) ("[A] right of way appurtenant to the land conveyed cannot be used by the owner of the dominant tenement to pass to or from other land adjacent to or beyond that to which the easement is appurtenant"); McLaughlin, 422 Mass. at 364 (stating easement may not be used to serve estate to which it is not appurtenant). In arguing that the Right of Way granted for the benefit of a portion of Gervis Parcel 1 may not now be used to access the remainder of Gervis Parcel 1 or Gervis Parcel 2, Plaintiff relies on the Murphy rule.

The parties filed their final summary judgment submissions on October 14, 2016. Three days prior, the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) issued a decision affirming the Murphy rule and declining to adopt a more "fact-based inquiry" that asked "'whether use of an easement by an adjacent parcel place[s] additional burdens on the servient estate,'" and, if so, whether such additional use 'unfairly burden[s] the servient estate . . . in a manner beyond the scope of that intended' in the original grant." Taylor, 475 Mass. At 686. The SJC declined to adopt the more flexible approach due to what the Court perceived as potential negative consequences: significant costs, the introduction of uncertainty in land ownership, longer litigation processes with less predictable outcomes, and financial constraints on owners of smaller servient parcels who are litigating against defendants with greater financial means. Taylor, 475 Mass. at 68889.

Charles E. Gibson did not own the House Lot or what is now Gervis Parcel 2 on the important date of December 28, 1916. The record establishes that the Right of Way is appurtenant only to the Triangle Lot and the Driveway Lot, his remaining parcels. The Gervis House is located on the House Lot portion of Gervis Parcel 1, which is not benefitted by the Right of Way. The record establishes that adjacent Gervis Parcel 2 is used primarily for recreational purposes, comprising a swimming pool, trees, shrubbery, storage shed, and a cabana. It does not have on it dwellings of any kind. Thus, Defendants argue that Gervis Parcel 2 must be considered accessory to and part of the residential use of Gervis Parcel 1. Even if that were true, Defendants' analysis assumes the House Lot had the appurtenant right to use the Right of Way, which it does not.

Despite Defendants' attempts to distinguish their situation, the SJC's reaffirmance of the bright-line Murphy rule in Taylor is clear: absent consent from the owner of the servient parcel, the use of an easement to benefit after-acquired property constitutes an overloading of the easement. Accordingly, Plaintiff's request for a permanent injunction will be ALLOWED, in part, to prevent overloading of the Right of Way by use of it for access to the House Lot and Gervis Parcel 2. This injunction does not leave the Gervis Parcels without access to a way. In an affidavit dated September 7, 2016, Defendant Robert M. Gervis stated that "Forest Avenue, the main street used to access our home, is a narrow, private way. Travel along Forest Avenue is frequently blocked or access is otherwise impaired for a variety of reasons. We have crossed the disputed [Right of Way] . . . primarily when access to Forest Avenue is blocked or otherwise impaired, as the [Right of Way] has often been the sole means of access to our home." The scope of access by way of Forest Avenue was not otherwise addressed in the parties' joint statement of material facts. Accepting Mr. Gervis' affidavit as providing the only facts about Forest Avenue, those facts do not rise to the level of a "substantial impracticality," Taylor, 475 Mass. at 690, and Taylor has recently reaffirmed that the Murphy rule is to be strictly applied, in spite of the inconveniences it may cause in specific situations. [Note 12]

IV. Conclusion

For the reasons discussed above, Defendants' motion for summary judgment is allowed in part and denied in part, and Plaintiff's cross motion is denied in part and allowed in part.

Judgment to issue accordingly.

The court addressed the motions to strike and Plaintiff's oppositions at the hearing, advising that it would disregard any assertions or facts not based on personal knowledge proffered in the affidavits, as well as the opinions expressed therein. The affidavit of Attorney Rosenberg, largely containing opinion testimony regarding actions of zoning officials of the City of Newton, is stricken in its entirety. The Buckley Plan has been addressed more fully in footnote 6, supra. Accordingly, this court confirms that Defendants' motions to strike were DENIED, except as qualified herein.

ARTHUR X. DUFFY, as TRUSTEE of SYLVAN AVENUE REALTY TRUST v. ROBERT M. GERVIS and LAURIE L. GERVIS.

ARTHUR X. DUFFY, as TRUSTEE of SYLVAN AVENUE REALTY TRUST v. ROBERT M. GERVIS and LAURIE L. GERVIS.