All the individual parties are family members who hold title to four adjoining lots in Falmouth that form a sort of family compound. The plaintiffs hold title to two of the lots; the defendants hold title to the other two. At issue is the lot in the middle, lot 250, currently owned by defendant Suzanne J. Keohane, Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I. The trustee seeks to build a house on lot 250, but the Town of Falmouth building commissioner refused to issue a building permit on the grounds that lot 250 was a nonconforming lot that had merged with one or more of the adjoining lots. The Town of Falmouth Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) issued a decision reversing the building commissioner's determination, and the plaintiffs appealed. The parties have now filed cross-motions for summary judgment. As discussed below, the court finds that the plaintiffs' presumption of standing has not been rebutted, and that the ZBA erred because lot 250 did not qualify for protection from merger under the Town of Falmouth Zoning By-Laws (Bylaw) because it was not vacant in 1981.

Procedural History

The Plaintiffs filed their complaint (Complaint or Compl.) in this action on March 11, 2016. On March 31, 2016, the answers of Suzanne H. Keohane, Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I (Suzanne Ans.), Patricia H. Keohane (Patricia Ans.), and Harold J. Keohane Individually and as Trustee of the Keohane Santuit Realty Trust (Harold Ans.) were filed. On April 6, 2016, the Plaintiffs' Answers to the Facts in Support of Affirmative Defenses of Suzanne H. Keohane Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I, Patricia H. Keohane, and Harold J. Keohane Individually and as Trustee of the Keohane Santuit Realty Trust were filed. The Case Management Conference was held on May 17, 2016.

On May 15, 2017, the Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment and Summary Judgment Brief were filed. On July 7, 2017, the Defendants' Opposition Brief to Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment and Brief in Support of Defendants' Cross Motion for Summary Judgment (Defs. Opp.) were filed. On July 31, 2017, the Plaintiffs' Summary Judgment Opposition and Reply were filed. On August 7, 2017, the Parties' Consolidated Statement of Undisputed, Material Facts with Responses (SOF) and Joint Summary Judgment Appendix (Appendix or App.) were filed. Also on August 7, 2017, Defendants' Motion to Strike Exhibits 15 and 16 and Portions of Exhibits 17 and 18 and All References Thereto and Reasons in Support Thereof (Motion to Strike), and Plaintiffs' Opposition to the Keohanes' Motion to strike were filed. The Court heard the motion to strike and the cross-motions for summary judgment on August 9, 2017, and took the motions under advisement. This Memorandum and Order follows.

Motion to Strike

The Defendants have moved to strike Exhibits 15 and 16 and portions of Exhibits 17 and 18 from the Appendix. The disputed exhibits submitted by the Plaintiffs are appropriate evidence to be considered by the court in the event that the Defendants rebut the Plaintiffs' presumption of standing. See 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700- 703, 703 n.15 (2012). Further, in large part, the Defendants' motion goes to the weight of the evidence rather than its admissibility. The Defendants' Motion to Strike is DENIED.

Summary Judgment Standard

Generally, summary judgment may be entered if the "pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court draws "all logically permissible inferences" from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991). "Summary judgment is appropriate when, 'viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.'" Regis College v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012), quoting Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991).

Undisputed Facts

The following facts are undisputed:

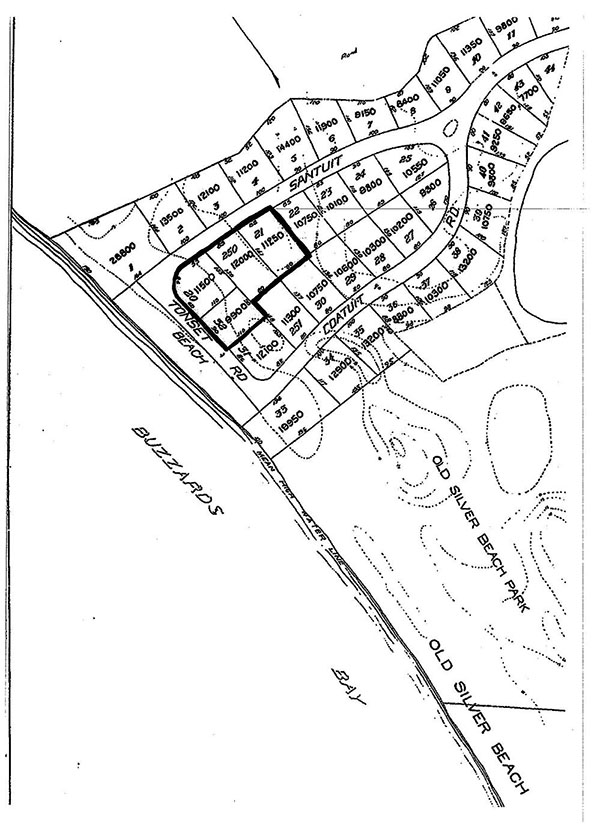

1. The properties relevant to this action are four contiguous lots in Falmouth, Massachusetts shown as lots 20, 21, 32, and 250 on a plan entitled "Plan of Lots at Old Silver Beach Village, West Falmouth Mass., Owned by Old Silver Beach Corporation," dated December 1926 and recorded with the Barnstable Registry of Deeds (registry) in Plan Book 20, Page 1-F1 (the 1926 Plan). Page F-1 of the 1926 Plan is attached as Exhibit A. SOF ¶ 68; App. Exh. 1, Tab C.

2. Cornelius K. Hurley, Jr. (Hurley, Jr.) is the record owner of lot 20. Compl. ¶ 1; Harold Ans. ¶ 1; Patricia Ans. ¶ 1; Suzanne Ans. ¶ 1.

3. Sheila H. Canty, Trustee of the Canty Family Realty trust, is the record owner of lot 21 by deed dated January 3, 2003, and recorded with the registry at Book 16186, Page 955. Compl. ¶ 3; Harold Ans. ¶ 3; Patricia Ans. ¶ 3; Suzanne Ans. ¶ 3.

4. Suzanne Keohane, Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I, is the record owner of lot 250 by deed dated February 1, 2016, and recorded with the registry at Book 29488, Page 300. Compl. ¶ 4; Harold Ans. ¶ 4; Patricia Ans. ¶ 4; Suzanne Ans. ¶ 4.

5. The Keohane Tonset Realty Trust is the record owner of lot 32 by deed dated January 17, 2012, and recorded with the registry at Book 26061, Page 209. SOF ¶ 98; App. Exh. 1, Tab BB.

6. Lot 250 is a nonconforming lot under the Bylaw because it contains approximately 12,000 square feet and is located in a Single Residence B (RB) zoning district which requires a minimum lot size of 40,000 square feet. SOF ¶¶ 37, 77.

7. The only interior demarcation between the four lots, which are otherwise open to each other, is a fence along the easterly boundary of lot 20, running southerly from Santuit Road and stopping short of the lot's southeastern corner, leaving lot 20 open to lot 250. SOF ¶ 7; App. Exh. 2, Tab 3.

8. The Town of Falmouth (Town) first adopted zoning in 1926. Under the 1926 Bylaw, lots in residential zoning districts were required to have 7,500 square feet of lot area. SOF ¶ 155-56; App. Exh. 12.

9. Mildred G. Hurley (Mildred) acquired lots 20 and 32 by deed dated April 27, 1946, and recorded with the registry at Book 648, Page 509. SOF ¶ 73; App. Exh 1, Tab A.

10. In 1946, lot 20 was improved with a single-family dwelling and contained approximately 11,500 square feet of lot area. Lot 32 was vacant land, containing approximately 9,900 square feet of lot area. SOF ¶ 74.

11. On February 22, 1957, the Town amended the Bylaw to increase the minimum lot size in a RB zoning district to 20,000 square feet, making lots 20, 21, 32, and 250 nonconforming. SOF ¶ 74, 77, 157; App. Exh. 13.

12. In 1957, lot 250 was owned by Old Silver Beach Trust in common with several other adjacent lots of land. SOF ¶ 158; App. Exh. 1, Tab AAA.

13. By identical deeds dated June 6, 1961, and November 15, 1961, recorded with the registry at Book 1117, Page 406, and Book 1137, Page 501 respectively, C. Keefe Hurley (Hurley, Sr.) and Mildred (together the Hurley parents) took title to lots 21 and 250 at tenants by the entirety. SOF ¶¶ 75-76; App. Exh. 1, Tab B.

14. At that time, lots 21 and 250 were vacant land, containing approximately 11,250 and 12,000 square feet of lot area respectively. SOF ¶ 77.

15. In 1961, the Hurley parents constructed a single-family dwelling on lot 21 to be used by the Hurley parents' adult children and their growing families, who would visit for several weeks at a time each year. SOF ¶ 3.

16. Also in 1961, the Hurley parents built a driveway for lot 21 which straddled the shared property line between lots 21 and 250, and a parking area on lot 250 for cars visiting lots 20 and 21. SOF ¶ 4.

17. The unimproved lots, 32 and 250, were used for recreation by the Hurley family. Some family members believed they were a single lot. SOF ¶ 5.

18. A stone wall ran along the respective frontage of lots 20 and 32 on Tonset and Santuit Roads. SOF ¶ 6.

19. After the Hurley parents purchased lots 21 and 250 in 1961, Hurley, Sr. installed a stockade fence along Santuit Road from the end of the stone wall to the easterly edge of the driveway leading to lot 21. SOF ¶ 6.

20. In 1962, the Hurley parents built a tennis court along the southern boundary of lots 21 and 250, with the majority of the tennis court being situated on lot 250. SOF ¶ 9; App. Exh. 1, Tab K.

21. In 1970, the Hurley parents moved to the Cape full-time, and lived in the house on lot 20 as their full time residence. SOF ¶ 153.

22. In 1983, the Town, attributing the tennis court to lot 250 only, included the tennis court in the real estate tax assessment for lot 250 and valued it at $3,200. App. Exh. 7.

23. The Hurley family shared maintenance of the four lots. In 1985, the Hurley parents purchased and installed a shed on lot 250 to store garden tools, maintenance equipment used for the upkeep of all four lots, and the tennis net during the off-season. SOF ¶ 12; App. Exh. 1, Tab K.

24. In 1989, the Hurley parents conveyed lot 21 to their daughter Sheila Canty (Canty) by deed dated December 8, 1989, and recorded with the registry at Book 7172, Page 208. SOF ¶ 13; App. Exh. 1, Tab L.

25. In 1991, the tennis court was damaged by a hurricane. Repairs made by Cape & Island Tennis were paid for by Robert Canty, who, together with his wife Sheila Canty, was the then owner of lot 21. SOF ¶¶ 161-62; App. Exh. 1, Tabs CCC, DDD.

26. Mildred conveyed lots 20 and 32 to the Hurley parents, husband and wife, as tenants by the entirety, by deed dated November 14, 1991, and recorded with the registry at Book 7782, Page 86. App. Exh. 1, Tab BBB.

Title to Lot 250:

27. The Hurley parents conveyed lot 250 to their son, Hurley, Jr., as Trustee of the C.K.H. Realty Trust, by deed dated November 14, 1991, and recorded with the registry at Book 7782, Page 84. SOF ¶ 14; App. Exh. 1, Tab M.

a. Hurley, Jr. as Trustee of the C.K.H. Realty Trust conveyed lot 250 to Harold Keohane by deed dated December 24, 1993, and recorded with the registry at Book 8989, Page 265. SOF ¶ 15; App. Exh. 1, Tab N.

b. By deed dated January 17, 2012, and recorded with the registry at Book 26061, Page 21, Harold Keohane conveyed lot 250 to the Keohane Santuit Realty Trust u/d/t/dated January 17, 2017 (Santuit Realty Trust). SOF ¶ 80; App. Exh. 1, Tabs AA, SS.

c. The Santuit Realty Trust is a nominee trust with its sole beneficiary being the Harold J. Keohane Trust u/d/t/ dated January 7, 1993. The beneficiaries of the Harold J. Keohane Trust are the Keohanes and their children Suzanne H. Keohane, Michaela Keohane, Michael Keohane, and Elizabeth K. Scott. SOF ¶¶ 81-82; App. Exh. 1, Tab SS.

d. In early 2016, Suzanne H. Keohane was appointed Trustee of the Santuit Realty Trust. SOF ¶ 83. By deed dated February 1, 2016, and recorded with the registry at Book 29488, Page 300, Suzanne H. Keohane Trustee of the Santuit Realty Trust conveyed lot 250 to Suzanne H. Keohane, Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I u/d/t dated January 22, 2016 (Irrevocable Trust). SOF ¶¶ 83-84; App. Exh. 1, Tab CC.

e. The beneficiaries of the Irrevocable Trust are the Keohanes and their children Suzanne H. Keohane, Michaela Keohane, Michael Keohane, and Elizabeth K. Scott. SOF ¶ 85.

Title to Lot 32:

28. The Hurley parents conveyed lot 32 to their daughter, Patricia Keohane, by deed dated December 24, 1993, and recorded with the registry at Book 8989, Page 263. SOF ¶ 16; App. Exh. 1, Tab O.

a. By deed dated January 17, 2012, and recorded with the registry at Book 26061, Page 209, Patricia Keohane conveyed lot 32 to the Keohane Tonset Realty Trust u/d/t dated January 17, 2012 (Tonset Realty Trust). SOF ¶ 98; App. Exh. 1, Tab BB.

b. The Tonset Realty Trust is a nominee trust with its sole beneficiary being the Patricia H. Keohane Trust u/d/t January 7, 1993. The beneficiaries of the Patricia H. Keohane Trust are the Keohanes and their children Suzanne H. Keohane, Michaela Keohane, Michael Keohane, and Elizabeth K. Scott. SOF ¶¶ 99-100.

Siting, Approval, and Construction of the Keohanes' House:

29. After Patricia and Harold Keohane (the Keohanes) separately acquired title to lots 32 and 250, the Keohanes consulted with Holmes and McGrath, Inc., Civil Engineers and Land Surveyors, who suggested that the Keohanes merge the two lots in order to increase the size of their prospective home. SOF ¶ 20; App. Exh. 1, Tab R.

30. Seeking to build a house on lot 32, Patricia Keohane filed a Notice of Intent with the Falmouth Conservation Commission and the Massachusetts DEP on August 14, 1998. The Notice describes the project site as one combined site, listing the addresses and assessor's numbers for both lots 32 and 250. SOF ¶ 22; App. Exh. 1, Tab S.

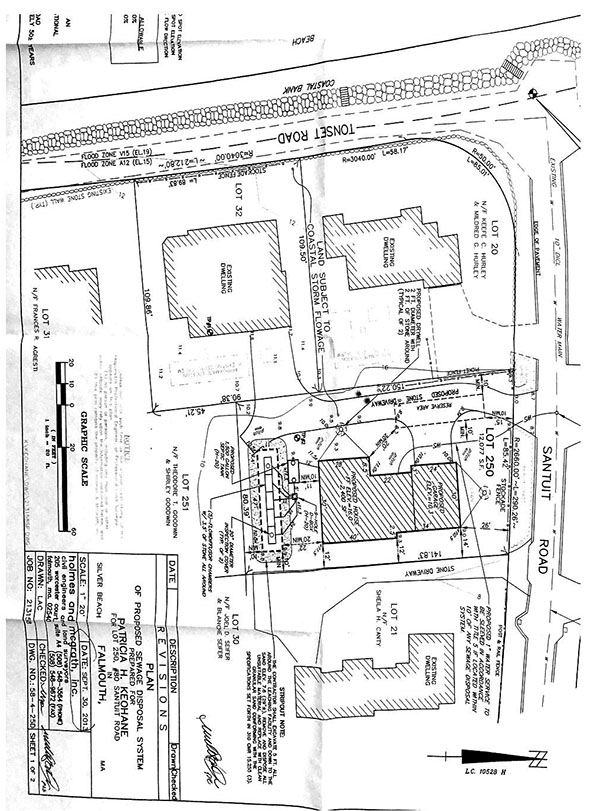

31. The Notice of Intent and the Falmouth Conservation Commission's approval in its October 28, 1998, Order of Conditions together describe the project as 21,000 square feet because the Keohanes proposed to construct a driveway on lot 250 to serve the house to be built on lot 32. SOF ¶ 23; App. Exh. 1, Tabs S, T.

32. On March 19, 1999, Patricia Keohane was granted a variance by the Falmouth Board of Health to allow the reserve soil absorption area of the septic system to be sited with a zero foot setback from the easterly boundary of lot 32 and a five foot setback from the northerly boundary of lot 32, provided that "an easement to provide access for the initial installation of the soil absorption system and all future upgrading, replacement, and routine maintenance requirements for the proposed system shall be granted by the owners of Lot 250 for the benefit of Lot 32." SOF ¶ 26; App. Exh. 1, Tab V.

33. The tennis court was removed in 1996. One of the four sections of fence which enclosed the court remains along the southerly border of lot 250 to this day. SOF ¶ 115.

34. In 2001, Falmouth Building Commissioner Eladio Gore (Gore or Building Commissioner) endorsed a letter agreeing that "Lot 32 Tonset Road is entitled to a building permit pursuant to the provisions of Section 240-66(C)(1) and (4) of the Falmouth Zoning Bylaw," without considering whether lot 32 was held in common with any adjoining lots other than lot 20. App. Exh. 1, Tab NN.

35. Construction of the Keohanes' house on lot 32 was completed between 2002 and 2003. SOF ¶ 21.

36. The Keohanes access their home on lot 32 by a driveway from Santuit Road over lot 250 which is approximately 150 feet long. SOF ¶ 28; App. Exh. 1, Tab W.

37. The Keohanes jointly applied for a construction loan to build the house on lot 32 and listed both lots 32 and 250 on the loan application. SOF ¶ 33(a); App. Exh. 1, Tab Y.

38. The Keohanes have paid annual dues to the Old Silver Beach Home Owner's Association and property taxes for lots 32 and 250 from their joint bank account. SOF ¶ 33(b).

39. The Keohanes have used lots 32 and 250 to host a variety of family gatherings including several family reunions for Harold Keohane's family, the Keohanes 40th Wedding Anniversary, and the wedding of Elizabeth Keohane Scott. Lot 250 has been used for guest parking and tents have been set up on both lots. SOF ¶ 33(d); App. Exh. 1, Tab Z.

40. By letter dated December 6, 2013, Edward W. Kirk, Esq. (Kirk), on behalf of Harold J. Keohane, Trustee of the Santuit Realty Trust, wrote to Gore, the Building Commissioner, requesting his agreement that lot 250 qualifies as a lawful nonconforming lot under each of §§ 240- 66(C)(2) and 240-66(C)(4) of the Bylaw. SOF ¶¶ 36, 129; App. Exh. 1, Tab GG.

41. Section 240-66(C)(2) of the Bylaw provides that:

Any lot not held in common ownership with any adjoining land as of 1 January 1981, not protected by Subsection C(1), shall be eligible to apply for a building permit if the lot has at least

[t]en thousand square feet of area in an AGR/RB District.

App. Exh. 4.

42. Section 240-66(C)(4) of the Bylaw provides that:

Any lot held in common ownership with such adjoining lots, vacant as of 1 January 1981, may be treated as not held in common ownership if, as of 1 January 1981, a dwelling was in existence on all other commonly held, contiguous lots, or if subsequent to 1 January 1981, the lot was no longer held in common ownership and a dwelling was permitted by special permit on each of such adjoining lots.

App. Exh. 4.

43. On January 6, 2014, Gore sent a letter to Kirk, declining to issue a letter of buildability after a preliminary investigation revealed that "lot 250 may have merged with one of the other contiguously owned lots," and seeking documentation to clarify the following "seeming inconsistencies:"

1. According to the 1/1/81 assessor's information, lot 250 had a structure on it and lot 032 was vacant.

2. According to GIS aerial photographs from 3/12/1986, it appears that the contiguous lots 250 and 032 did not have a house on said lots. However, it appears that lot 250 had a tennis court.

3. Also according to records it appears that lot 250 has a driveway to access a new structure on lot 032.

SOF ¶ 39; App. Exh. 1, Tab HH.

44. On July 23, 2014, Kirk wrote to Gore responding to the issues raised in Gore's January 6, 2014 letter. SOF ¶ 40; App. Exh. 1, Tab II.

45. Gore issued a final determination on July 2, 2015, (Determination) concluding that lot 250 had merged with one of the other contiguous lots and is not a buildable lot. SOF ¶¶ 40, 138; App. Exh. 1, Tab JJ.

46. On July 29, 2015, Harold J. Keohane, Trustee of the Santuit Realty Trust appealed Gore's determination to the ZBA. SOF ¶¶ 41, 139; App. Exh. 1, Tab KK.

47. By its written decision dated February 22, 2016 (Decision), the ZBA voted unanimously to overturn "the Building Commissioner's Determination that Lot 250 (80 Santuit Road) is not a buildable lot." SOF ¶¶ 44, 140; App. Exh. 1, Tab LL.

48. In the Decision the ZBA found, in relevant part, that:

5. The Board finds in 1989 common ownership of Lots 250 and 21 was severed when Lot 21 was conveyed to Sheila Canty.

6. The Board finds that Lot 250 has not been in common ownership with any lot since 1989

14. The Board further finds that Section 240-66C. (4) offers protection to Lot 250 so as to be deemed not held in common ownership with adjacent Lot 21

18. The Board finds that an accessory structure, in this case a tennis court that crossed the property lines of Lot 21 and Lot 250, was eliminated in 1996

and therefore the lot has been vacant

20. The Board finds that because the parents (C. Keefe Hurley and Mildred Hurley) purchased lots and later conveyed them to their children does not indicate an intent to 'control' the lands; that the various ownerships of lots at various times did not constitute "checkerboarding"

by any one person; and that the 'doctrine of merger' did not occur for Lot 21 and Lot 250 as said lots have always been treated and assessed as separate lots and conveyed separately.

22. The Board finds that Lot 250 qualifies for the protection provided by Section 240-66C. (2) and (4) based on the findings set forth herein.

App. Exh. 1, Tab LL.

49. On February 3, 2016, Suzanne H. Keohane, Trustee of the Irrevocable Trust granted Patricia Keohane, Trustee of the Tonset Realty Trust an easement over and across lot 250, as appurtenant to, and for the benefit of, lot 32 for the purpose of providing pedestrian and vehicular access between Santuit Road and lot 32. The easement is recorded with the registry at Book 29488, Page 306.

SOF ¶ 101; App. Exh. 1, Tab X.

50. The Plaintiffs assert that they will be injured by the construction of a house on lot 250, specifically by the "increase in the overall density of [an] already, overly dense seaside village." Compl. ¶ 110; SOF ¶¶ 181-182.

a. The Keohanes had a plan prepared by Holmes and McGrath, entitled "Plan of Proposed Sewage Disposal System Prepared for Patricia H. Keohane for Lot 250, #80 Santuit Road in Silver Beach, Falmouth, MA," (the 2013 Plan) which depicts an elevated 2,400 square foot house with attached garage located on lot 250. The 2013 Plan is attached as Exhibit B. Compl. ¶ 22-23; Harold Ans. ¶ 22-23; Patricia Ans. ¶ 22-23; Suzanne Ans. ¶ 22-23. App. Exh. 1, Tab OO.

b. Sheila Canty asserts that the construction of a house on lot 250 will injure her particularly because (1) the size and placement of the house will cast shadows onto lot 21, reduce available light, and decrease privacy; (2) a house on lot 250 will increase existing drainage problems on lots 250 and 21; and (3) the value of her property will decrease. SOF ¶ 181.

c. Hurley, Jr. asserts that the construction of a house on lot 250 will injure him particularly because (1) the house will cast shadows on lot 20; (2) the house will reduce his privacy which is of particular significance to him as lot 20's front yard abuts Tonset Road and Old Silver Beach, and is not private; (3) the house will crowd an already undersized lot and exacerbate existing drainage problems by covering a significant portion of the lots pervious surface; (4) the 2013 Plan shows that the driveway on lot 250 will be moved closer to lot 20 and will now serve two lots, increasing noise, creating parking difficulties for guests on lot 250, and creating parking spillover onto a protected dune area on lot 20; and (5) the value of his property will decrease.

SOF ¶ 182.

Discussion

The Plaintiffs seek to have the ZBA's Decision that lot 250 is buildable annulled on the grounds that lot 250 is not a legally buildable lot. The questions before the court on these cross-motions for summary judgment are (1) whether the Plaintiffs have standing to challenge the Decision of the ZBA; (2) whether lot 250 is a buildable lot under the protections afforded by Bylaw; and (3) whether the Plaintiffs' respective adverse possession claims are perfected and cause lot 250 to become a new lot for the purposes of G.L. c. 40A, § 6, which must comply with existing dimensional requirements.

1. Standing

The Defendants challenge the Plaintiffs' standing to maintain their appeal of the Decision overturning the Building Commissioner's Determination. In order to have standing to challenge the issuance of the Decision, the Plaintiffs must be "person[s] aggrieved" by the Decision. G.L. c. 40A, § 17; Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 117 (2011); Planning Bd. of Marshfield v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Pembroke, 427 Mass. 699 , 702-703 (1998). Persons entitled to notice under G.L. c. 40A, § 11, including abutters to the subject property and abutters to abutters within 300 feet of the subject property, are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they are aggrieved within the meaning of § 17. G.L. c. 40A, § 11; 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012); Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Choate v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Mashpee, 67 Mass. App. Ct. 376 , 381 (2006). The Plaintiffs are direct abutters to lot 250 and therefore entitled to the rebuttable presumption that they are aggrieved.

In the zoning context, a defendant can rebut an abutter's presumption of standing at summary judgment in three ways. First, the defendant can show "that, as a matter of law, the claims of aggrievement raised by an abutter, either in the complaint or during discovery, are not interests that the Zoning Act is intended to protect." 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 702, citing Kenner, 459 Mass. at 120. Second, "where an abutter has alleged harm to an interest protected by the zoning laws, a defendant can rebut the presumption of standing by coming forward with credible affirmative evidence that refutes the presumption." Id. at 703. "[T]he defendant may present affidavits of experts establishing that an abutter's allegations of harm are unfounded or de minimis." Id. at 702, citing Kenner, 459 Mass at 119120, and Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 2324 (2006). Third, a defendant need not present affirmative evidence that refutes a plaintiff's basis for standing; "it is enough that the moving party demonstrate by reference to material described in Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c), [ 365 Mass. 824 (1974),] unmet by countervailing materials, that the party opposing the motion has no reasonable expectation of proving a legally cognizable injury." Id. at 703, quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35; see Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706 , 716 (1991). "Once the presumption of standing has been rebutted successfully, the plaintiff [has] the burden of presenting credible evidence to substantiate the allegations of aggrievement, thereby creating a genuine issue of material fact whether the plaintiff has standing and rendering summary judgment inappropriate." 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 703 n.15, citing Marhefka v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Sutton, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 515 , 519521 (2011).

The Defendants have not rebutted the Plaintiffs' presumption of standing in any of the three ways discussed above. First, in their challenge to the Plaintiffs' standing the Defendants argue that "[c]oncerns of diminished open space, other aesthetics, including, but not limited to, ocean views, and property values are insufficient to establish a definite violation of a private right, property interest or legal interest." Defs. Opp. at p. 20. To rebut the Plaintiffs' presumption of standing with this argument the Defendants were required to show that the Plaintiffs' claims of aggrievement are not interests that G.L. c. 40A or the Bylaw were intended to protect. Such protected interests can arise from a bylaw's express language or implicitly from the intent of the bylaw's provisions. Marhefka v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Sutton, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 515 , 518-519 (2011); see, e.g., Monks v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Plymouth, 37 Mass. App. Ct. 685 , 688 (1994) (bylaw expressly protected visual character or quality of the neighborhood); Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 8 , 12 (2009) (requirements regarding lot size, lot width, and side yard are intended to further the general purposes of the bylaw).

Plaintiffs have articulated aggrievement due to shadows, decreased light, loss of privacy, exacerbation of drainage problems, and massing caused by the increased density of a new house on the nonconforming Lot 250. SOF ¶¶ 157, 181, 182; App. Exh. 13. Section 240-1 of the Bylaw, in relevant part, provides:

The purpose of this chapter is to lessen congestion in the streets; to conserve health; to secure safety from fire, flood, panic and other dangers; to provide adequate light and air; to prevent overcrowding of land; to avoid undue concentration of population; to encourage housing for persons of all income levels; to facilitate the adequate provision of transportation, water supply, drainage, schools, parks, open space, and other public requirements; to conserve the value of land and buildings, including the conservation of natural resources and the prevention of blight and pollution of the environment

App. Exh. 4. The Plaintiffs' claims of aggrievement relating to decreased light from shadows, exacerbation of drainage problems, and increased density are all interests which the Bylaw expressly intends to protect, and are ones generally protected under G.L. c. 40A. Sheppard, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 12; Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 297 (2008). As the Defendants have not shown that the Plaintiffs' claims of aggrievement are not based on protected interests, and several of the Plaintiffs' claimed harms are in fact harms to interests protected by the Bylaw, the Defendants have not rebutted the presumption of standing for lack of a legally protected interest.

Second, the Defendants do not present any affirmative evidence which, if credited, would establish that the Plaintiffs' allegations of harm are unfounded or de minimis. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 702. Rather, the Defendants attack the Plaintiffs' claims by arguing that the Plaintiffs have not provided enough admissible evidence to support their alleged injuries. This argument misplaces the burden at this stage of the standing analysis. Where the Plaintiffs have the presumption of standing and have in fact articulated claims of aggrievement to interests protected by G.L. c. 40A or the Bylaw, the Defendants bear the burden of coming forward with credible admissible evidence to refute the presumption. Id. They have not done so.

Third, the Defendants, in their discussion of the weight of the Plaintiffs' evidence regarding shadows, privacy, noise, traffic, and property value, do not demonstrate that the Plaintiffs have "no reasonable expectation of proving a legally cognizable injury." Id. at 703, quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35; see Kourouvacilis, 410 Mass. at 716. The Defendants argue at length that the lay opinions of the Plaintiffs, with respect to the harms that they allege, are speculative and are insufficient evidence to confer standing. This is not correct. As discussed, the Plaintiffs have presented evidence of their harms in the form of their own observations based on plans for the proposed house. Compl. ¶ 110; SOF ¶¶ 181-182; App. Exh. 1, Tab OO. The Plaintiffs, as abutters with the presumption of standing, articulated particular injuries which need not be further supplemented with such "credible evidence to substantiate allegations of aggrievement" until after the presumption of aggrieved status has been rebutted. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 703 n.15.

The Plaintiffs have a presumption of standing. They have articulated grounds for aggrievement that involve harm to interests protected by c. 40A and the Bylaw, and have presented evidence supporting those harms. The Defendants have offered no evidence to counter those harms or demonstrate that the Plaintiffs cannot prove those harms. The Defendants have not rebutted the Plaintiffs' presumption of standing, and the Plaintiffs have standing to bring this action to challenge the Decision.

2. ZBA Decision

The Plaintiffs seek annulment of the Decision. They argue that lot 250 is not a buildable lot because it is a nonconforming lot that (1) is not protected under G.L. c. 40A, § 6, or the Bylaw and (2) has merged with one of the other adjoining lots. The Defendants defend the ZBA's buildability determination by arguing primarily that §§ 240-66(C)(2) and 240-66(C)(4) of the Bylaw protect the status of lot 250 as a buildable lot.

An appeal of a zoning board of appeals decision is de novo; that is, in an action under § 17 the "court shall hear all the evidence pertinent to the authority of the board . . . and determine the facts, and, upon the facts as so determined, annul such decision if found to exceed the authority of such board . . . or make such other decree as justice and equity may require." G.L. c. 40A, § 17. Section 17 review of a local board's decision involves a "'peculiar' combination of de novo and deferential analyses." Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc. v. Board of Appeal of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381 (2009). The court is obliged to find facts de novo and may not give any weight to those facts found by the local board. G.L. c. 40A, § 17; Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 72 (2003) ("In exercising its power of review, the court must find the facts de novo and give no weight to those the board has found."); Kitras v. Aquinnah Plan Review Comm., 21 LCR 565 , 570 (2013) (noting the court must "review the factual record without deference to the board's findings"). After finding the facts de novo, the court's "function on appeal" is "to ascertain whether the reasons given by the [board] had a substantial basis in fact, or were, on the contrary, mere pretexts for arbitrary action or veils for reasons not related to the purpose of the zoning law." Vazza Props., Inc. v. City Council of Woburn, 1 Mass. App. Ct. 308 , 312 (1973). The court, however, must give deference to the local board's decision and may only overturn a decision if it is "based on a legally untenable ground, or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary." MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 639 (1970), citing Gulf Oil Corp. v. Board of Appeals of Framingham, 355 Mass. 275 , 277 (1969); Britton, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 72; Kitras, 21 LCR at 570.

The validity of the ZBA Decision turns on whether, as a matter of law, lot 250 is a buildable lot. Lot 250 became dimensionally nonconforming when the Bylaw was amended in 1957, but it may remain buildable today if it is protected by G.L. c. 40A, § 6, or a more generous provision of the Bylaw. The answer to that question depends, in turn, on whether lot 250 could be deemed to have merged with any of the adjoining lots 20, 21, or 32. "A basic purpose of the zoning laws is 'to foster conforming lots.'" Asack v. Bd. of Appeals of Westwood, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 733 , 736 (1999), quoting Murphy v. Kotlik, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 410 , 414 n.7 (1993). To this end, the doctrine of merger provides that "adjacent lots in common ownership will normally be treated as a single lot for zoning purposes so as to minimize nonconformities." Seltzer v. Bd. of Appeals of Orleans, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 521 , 522 (1987). It is well settled that "a landowner will not be permitted to create a dimensional nonconformity if he could have used his adjoining lot to avoid or diminish the nonconformity." Planning Bd. of Norwell v. Serena (Serena), 27 Mass. App. Ct. 689 , 690 (1989), S.C., 406 Mass. 1008 (1990). "The statutory 'grandfather' provision contained in G.L. c. 40A, § 6, incorporates this doctrine by providing protection from increases in lot area and frontage requirements only to nonconforming lots that are not held in common ownership with any adjoining land. While a town may choose to adopt a more liberal grandfather provision, it must do so with clear language." Carabetta v. Bd. of Appeals of Truro, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 266 , 269 (2008). Once merger occurs, it cannot be undone. "A person owning adjoining record lots may not artificially divide them so as to restore old record boundaries to obtain a grandfather nonconforming exemption; to preserve the exemption the lots must retain 'a separate identity.'" Asack, 47 Mass. App. Ct. at 736, quoting Lindsay v. Bd. of Appeals of Milton, 362 Mass. 126 , 132 (1972).

a. G.L. c. 40A, §6

As a threshold question the court must address whether lot 250 was afforded grandfather protection under G.L. c. 40A, § 6, at the time that it became dimensionally nonconforming. The fourth paragraph of § 6 provides:

Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to a lot for single and two-family residential use which at the time of recording or endorsement, whichever occurs sooner was not held in common ownership with any adjoining land, conformed to then existing requirements and had less than the proposed requirement but at least five thousand square feet of area and fifty feet of frontage. Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirement of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply for a period of five years from its effective date or for five years after January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, whichever is later, to a lot for single and two family residential use, provided the plan for such lot was recorded or endorsed and such lot was held in common ownership with any adjoining land and conformed to the existing zoning requirements as of January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, and had less area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirements than the newly effective zoning requirements but contained at least seven thousand five hundred square feet of area and seventy-five feet of frontage, and provided that said five year period does not commence prior to January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, and provided further that the provisions of this sentence shall not apply to more than three of such adjoining lots held in common ownership.

Lot 250, having a lot area of approximately 12,000 square feet, first became nonconforming in 1957 when the Bylaw was amended to increase the required lot size in a RB district to 20,000 square feet. At the time of the amendment, lot 250 was held in common together with adjacent lots by the Old Silver Beach Trust. Therefore, lot 250 is not protected by § 6 from the increased dimensional requirements of the Bylaw because it was held in common ownership at the time it became nonconforming and did not comply with the dimensional requirements of the Bylaw as of January 1, 1976. But for the presence of a more generous Bylaw provision, lots 21 and 250 merged under the ownership of the Old Silver Beach Trust and lot 250 would not be buildable today.

b. Bylaw § 240-66(C)

Section 240-66(C) of the Bylaw provides more liberal relief for nonconforming lots than that found in G.L. c. 40A, §6. Specifically, lot 250 may be buildable if it complies with § 240- 66(C)(2) of the Bylaw. Section 240-66(C)(2) states:

Any lot not held in common ownership with any adjoining land as of 1 January 1981, not protected by Subsection C(1), shall be eligible to apply for a building permit if the lot has at least

[t]en thousand square feet of area in an AGR/RB District.

"This is the type of indulgent bylaw language intended to offer protection from the merger doctrine, should adjacent properties later come into common ownership." Esposito v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Falmouth, Mass. Land Ct., No. 09 MISC 396701 (Mar. 11, 2013), aff'd, 87 Mass. App. Ct. 1124 (2015), citing Preston v. Bd. of Appeals of Hull, 51 Mass. App. Ct. 236 , 240 (2001) and Seltzer, 24 Mass. App. Ct. at 522-523 (1987). This type of "snapshot" provision looks at the status of the lot at a specific point in time. The lot's compliance with the provision on the date of the snapshot determines whether it is buildable at any time in the future. Consequently, if lot 250 complied with §240-66(C)(2) in 1981, it would remain buildable today irrespective of the history of use and ownership by the Keohanes since they took title to lots 32 and 250 in 1993. Section 240-66(C)(4) further provides:

Any lot held in common ownership with such adjoining lots, vacant as of 1 January 1981, may be treated as not held in common ownership if, as of 1 January 1981, a dwelling was in existence on all other commonly held, contiguous lots, or if subsequent to 1 January 1981, the lot was no longer held in common ownership and a dwelling was permitted by special permit on each of such adjoining lots.

The effect of § 240-66(C)(4) is to create an exception for certain lots held in common with adjoining lots on January 1, 1981 (hereafter 1981) [Note 1], so that such lots get the benefit of § 240- 66(C)(2).

Thus, the ZBA erred, as a matter of law, in basing its Decision on the ownership status of lot 250 and lot 21 in 1989. Rather, the inquiry under § 240-66(C) is to determine, first, what lots were held in common ownership with lot 250 in 1981. It is undisputed that, in 1981, lots 21 and 250 were adjoining lots commonly held by the Hurley parents, while title to adjoining lots 20 and 32 was in Mildred's name alone. This separate ownership does not necessarily mean that the two sets of lots were not commonly owned. Rather, the question depends on who controlled the lots and how they were used. In Serena, the Appeals Court observed that "[t]he crux [of common ownership], thus, was not the form of ownership, but control: did the landowner have it 'within his power', i.e., within his legal control, to use adjoining land so as to avoid or reduce the nonconformity?" Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 691 (holding that common ownership of adjacent properties existed where defendants held one lot jointly and another as trustees and sole beneficiaries of a trust). The Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) affirmed the Land Court judge's conclusion that the "Serenas were entitled only to one building permit for the combined lots because the Serenas could use the two lots 'as one if they so chose.'" Planning Bd. of Norwell v. Serena, 406 Mass. 1008 , 1008 (1990), quoting Serena, Land Ct., No. 122914, slip op. at 8 (Jan. 22, 1988). Similarly, in Sorenti v. Bd. of Appeals of Wellesley, 354 Mass. 348 (1963), the SJC found common ownership where the plaintiff held title to a lot with insufficient frontage and title to the adjacent lot was held for the plaintiff by a straw. Id.; see Russo v. Town of Hubbardston Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 19 LCR 50 , 52 (2011) ("The rationale behind the reasoning in both Serena and Sorenti is that it is proper to look beyond record ownership and determine whether 'the landowner ha[s] it

within his legal control, to use the adjoining land so as to avoid or reduce nonconformity.' Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 691"). Where lots in a proposed subdivision were held separately by a business corporation, a trust, and two individuals, the Appeals Court found that "[w]e may disregard the shell of purportedly discrete legal persons engaged in business when there is active and pervasive control of those legal persons by the same controlling person and there is a confusing intermingling of activity among the purportedly separate legal persons while engaging in a common enterprise." DiStefano v. Town of Stoughton, 36 Mass. App. Ct. 642 , 645 (1994).

There is evidence in the record showing sufficient control by both Hurley parents together to support a finding that the two pairs of lots were only nominally separate as a matter of record title. Particularly, the use of the tennis court and parking area on lot 250 for the benefit of lots 20 and 21, and the ease with which the Hurley parents retitled each lot between 1989 and 1993 would support this conclusion. Such a conclusion would result in a finding that in 1981 lot 250 was held in common with three other adjacent lots, only two of which had existing dwellings, and is therefore not buildable under § 240-66(C) of the Bylaw. The record also shows, however, that various officials of the Town have on at least two occasions found that the four lots were not held in common ownership. In 2001, the Building Commissioner endorsed a letter agreeing to the status of lot 32 as a buildable lot; the common ownership of all four lots together was not considered. Most recently in the Decision the ZBA, properly positioned to consider the common ownership of all four lots together, found that lot 250 had not been in common ownership with any other lots since 1989 when lot 21 was conveyed to Sheila Canty. The ZBA reached this finding despite that fact that from 1989 to 1991 the remaining lots 20, 32, and 250 were still titled to one or both of the Hurley parents.

Given that the court "must give 'substantial deference' to a board's interpretation of its zoning bylaws and ordinances," Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of N.Y., Inc., 454 Mass. at 381, quoting Manning v. Boston Redevelopment Auth., 400 Mass. 444 , 453 (1987), due to its "home grown knowledge about the history and purpose of its town's zoning by-law," Duteau v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Worcester, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 664 , 669 (1999), there is an issue of fact as to whether all four lots were held in common ownership in 1981. A finding one way or the other would require the drawing of an inference that is impermissible on a motion for summary judgment. The court need not deny the cross-motions, however. The question of lot 250's status as a buildable lot can still be determined on the undisputed facts before the court.

There is no dispute that lot 250 and lot 21 were held in common ownership in 1981. Thus, lot 250 does not qualify for the protection of § 240-66(C)(2) unless it qualifies as a buildable lot under the provisions of § 240-66(C)(4). That section provides that a commonly held lot in 1981 is buildable only if, in 1981, it was vacant and there was a dwelling on the adjoining commonly held lot, or if the lots came into separate ownership after 1981 and a dwelling was permitted by special permit on the other lots. Bylaw § 240-66(C)(4). A dwelling was built on lot 21 in 1961 and was on the lot in 1981; moreover, no provision of the Bylaw allows for a dwelling on lot 250 or lot 21 by special permit. The only remaining question to determine whether lot 250 is buildable under § 240- 66(C)(4) is whether it was vacant in 1981.

The parties do not dispute that in 1981 there was a parking area, a portion of the driveway that served lot 21, and a tennis court located on lot 250. The tennis court was situated along the southern lot lines of lots 21 and 250 with the majority of the tennis court being located on lot 250. [Note 2]

The parties' arguments over the vacancy of lot 250 in 1981 come down to whether the presence of the tennis court is fatal to a finding that lot 250 was vacant within the meaning of the Bylaw.

The Bylaw does not define what "vacant" means. It defines a "dwelling" as:

A building or portion thereof used exclusively for residential occupancy including one-family, two-family and multifamily dwellings, but not including commercial accommodations used, or intended for use, by single or multiple families, as the case may be, for living, sleeping, cooking and eating.

Bylaw § 240-13. There was no dwelling on lot 250 in 1981. The Bylaw goes on to define a "structure" as:

Anything constructed or erected, the use of which requires fixed location on the ground or attachment to something located on the ground, including but not limited to tennis or similar sports courts

Bylaw § 240-13. Applying the Bylaw's definitions, the tennis court on lot 250 was a structure for the purposes of the Town's zoning.

The absence of a dwelling on lot 250 does not necessarily mean that the lot was vacant in 1981. A substantial and permanent structurethe tennis courtwas in place on lot 250 from 1962 until it was removed in 1996. The courts of the Commonwealth have had few opportunities to interpret the meaning of the word vacant in the context of a zoning bylaw. See Kibbe v. Town of Douglas, 69 Mass. App. Ct. 1108 (2007) (Rule 1:28 decision) ("the locus was not vacant in 1970 when the town adopted the zoning bylaws, because the trailerwhich fell within the definition of a mobile home as set forth in the town zoning bylawsremained on the locus."); Ryder v. Crawford, 16 LCR 326 , 328 (2008) ("The absence of any reported decision on the proper interpretation of 'vacant,' however may be attributable to the fact the definition of the word is commonly understood by the general public. Black's Law Dictionary defines 'vacant' as '[e]mpty; unoccupied

' Black's law Dictionary 1546 (7th ed.1999). Accordingly, the court finds and rules that the presence of the stone barn results in locus being neither empty nor unoccupied."). However, in the Decision the ZBA found that the "tennis court

was eliminated in 1996

and therefore has been vacant." Decision at ¶ 18. Giving proper deference to the ZBA's interpretation of their Bylaw would suggest that lot 250 only became vacant after the tennis court was removed in 1996.

This deference is supported by the undisputed facts. The tennis court, being in existence on the ground for more than 30 years, was more than some transient or ephemeral, temporary structure. By at least 1983, the tennis court was included in the real estate tax assessment for lot 250, being valued at $3,200. Considering the tennis court's size, prolonged existence, the value that it added to lot 250, the fact that it is specifically defined as a structure by the Bylaw, and the ZBA's own suggestion that its existence precluded vacancy, it would be unreasonable to conclude that, with the tennis court's presence, lot 250 was vacant in 1981. The court finds as a matter of law that lot 250 was not a vacant lot on January 1, 1981.

Lot 250 was held in common with at least one other adjoining lot which had an existing dwelling in 1981. However, because of the presence of the tennis court, lot 250 was not vacant at that time and therefore is not afforded the protection of § 240-66(C)(4). Consequently, lot 250 must be treated as though it was in common ownership with lot 21 on January 1, 1981, is not eligible for a building permit pursuant to § 240-66(C)(2), and therefore is not a buildable lot. As a matter of law lot 250 is not a buildable lot and the Decision of the ZBA must be annulled as it was based on a legally untenable ground.

3. Adverse Possession

"Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive, and adverse for twenty years." Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). Material facts are in dispute with respect to the adversity and exclusivity of the uses claimed by the Plaintiffs, making summary judgment on the adverse possession claims improper at this time.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment is ALLOWED in part and DENIED in part, and the Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. Judgment cannot enter at this time, as the Plaintiffs' adverse possession claim remains open. A telephone status conference is set down for February 23, 2018 at 9:30 am.

SO ORDERED

CORNELIUS K. HURLEY, JR., individually and As Trustee of the C.K.H. Realty Trust, and SHEILA H. CANTY, Trustee of the Canty Family Realty Trust, v. SUZANNE H. KEOHANE, Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I, HAROLD J. KEOHANE individually and in his Capacity as Trustee of the Keohane Santuit Realty Trust, PATRICIA H. KEOHANE, FALMOUTH ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, and KIMBERLY BIELAN, KENNETH FOREMAN, TERRANCE HURRIE, EDWARD VAN KEUREN, PAUL MURPHY, and MARK COOL, as they are the members of the FALMOUTH ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS.

CORNELIUS K. HURLEY, JR., individually and As Trustee of the C.K.H. Realty Trust, and SHEILA H. CANTY, Trustee of the Canty Family Realty Trust, v. SUZANNE H. KEOHANE, Trustee of the Harold J. Keohane Irrevocable Income Only Trust I, HAROLD J. KEOHANE individually and in his Capacity as Trustee of the Keohane Santuit Realty Trust, PATRICIA H. KEOHANE, FALMOUTH ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, and KIMBERLY BIELAN, KENNETH FOREMAN, TERRANCE HURRIE, EDWARD VAN KEUREN, PAUL MURPHY, and MARK COOL, as they are the members of the FALMOUTH ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS.