In this action, Plaintiffs challenge the affirmance by the Town of Sherborn Zoning Board of Appeals (Board), whose members are Defendants, of a permit issued by the town's Zoning Enforcement Officer (ZEO). The permit allows the construction of a single-family residence on a vacant lot (Lot 69F) owned by Defendants. Plaintiffs live directly across the street from Lot 69F. They allege it is not buildable under the Sherborn Zoning By-Laws and the Board erred in upholding the permit by incorrectly interpreting the By-Laws' method of determining lot width. By agreement of the parties, the correct determination of "minimum lot width" was the only issue at trial, as the parties agreed Lot 69F complies with all other use and dimensional requirements of the By-Laws. This court does not reach the merits of Plaintiffs' appeal pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 17, finding and ruling, after trial, that Plaintiffs do not have standing to challenge the Board's decision.

Prior to trial, the court took a view of and walked throughout the parties' properties. Four days of trial took place in January 2018. [Note 1] Michael Penney, a licensed professional engineer, Emily Pilotte, a potential buyer of Lot 69F, Sue McPherson, a realtor, and Daniel A. O'Driscoll, a professional land surveyor, testified for Defendants. David Humphrey, a professional land surveyor, and Paul Hutnak, a professional engineer, testified for Plaintiffs. Plaintiff Robert Murchison and Defendant Merriann Panarella also testified. [Note 2] Thirty Exhibits

were entered in evidence, including photographs. As discussed below, this court finds and rules Plaintiffs are not "person[s] aggrieved" and do not have standing to maintain this zoning appeal. [Note 3] This action will be DISMISSED.

Based on an agreed statement of facts, stipulations, exhibits, and the credible testimony introduced at trial, and the reasonable inferences drawn therefrom, this court finds the following facts:

The Parties' Properties

1. Plaintiffs' property, Lot 69F, is a vacant three-acre parcel of land, with 251 feet of continuous frontage on Lake Street, a public way designated as a "scenic road." [Note 4] Lot 69F is currently undeveloped, and has been cleared in anticipation of construction of a single-family residence.

2. Plaintiffs live at 177 Lake Street, which is located across the street from Lot 69F (Plaintiffs' Property). Both properties are located in a "Residence C" zoning district.

Relevant Provisions of the By-Laws

3. Under By-Laws Section 4.2, titled "Schedule of Dimensional Requirements," lots in a Residence C zoning district require, among other things, the following dimensional requirements: 1) a three-acre minimum lot size; 2) minimum continuous frontage of 250 feet; 3) a minimum lot width of 250 feet; 4) minimum front setback of sixty feet; 5) minimum side setback of forty feet; and 6) a minimum rear setback of thirty feet.

4. An asterisk in Section 4.2 notes that "minimum lot width" is to be "[m]easured both at front setback line and at building line. At no point between the required frontage and the building line shall lot width be reduced to less than 50 feet, without an exception from the Planning Board."

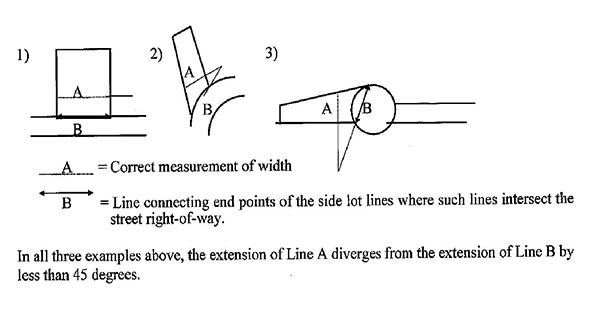

5. Section 1.5 of the By-Laws, "Definitions," defines "building line" as "[a] line which is the shortest distance from one side line of the lot to any other side line of the lot and which passes through any portion of the principal building and which differs by less than 45° from a line which connects the end points of the side lot lines at the point at which they intersect the street right-of-way."

6. The By-Laws do not contain a definition of "front setback line."

7. Section 1.5 defines "Width, Lot" as "[a] line which is the shortest distance from one side line of a lot to any other side line of such lot, provided that the extension of such line diverges less than 45° from a line, or extension thereof, which connects the end points of the side lot lines where such lines intersect the street right-of-way." The definition also includes the following illustration and commentary:

(see image below)

8. None of the proposed lines put forth by Plaintiffs or Defendants to support their respective interpretations of "lot width" diverge more than 45°.

Administrative Process

9. The ZEO issued a foundation permit for a single-family residential structure on Lot 69F on June 29, 2016. Plaintiffs timely filed a notice of appeal on July 19, 2016. The Board held a duly noticed and advertised public hearing on Plaintiffs' appeal of the ZEO's issuance of a foundation permit on September 14, 2016, and October 5, 2016, and issued its decision unanimously upholding the ZEO's issuance of the permit.

Plaintiffs' Standing

10. Section 1.2 of the By-Laws, "Purpose," states that the purpose of the By-Laws is "to promote the health, convenience and welfare of the inhabitants and to accomplish all other objects of zoning."

11. By-Laws Section 1.3, "Basic Requirements," provides "[n]otwithstanding any other provision of these By-Laws, any building or structure or any use of any building, structure or premises is prohibited if it is injurious, obnoxious, offensive, dangerous, or a nuisance to the community or to the neighborhood, by reason of the following:

Noise Gases

Vibrations Dust

Concussion Harmful fluids or substances

Odors Danger of fire or explosion

Fumes Smoke

Electronic interference Excessive drawdown of groundwater

Debris/refuse Lighting

or if it discharges into the air, soil water or groundwater any industrial, commercial or other kinds of waste, petroleum products, chemicals . . . or pollutants . . . or has any other objectionable features detrimental to the neighborhood health, safety, groundwater, convenience, morals or welfare."

12. The By-Laws' only references to "storm water" are in reference to "Wireless Communications Facilities," in Section 5.8, and "Large-Scale Ground Mounted Solar Photovoltaic Facilities" in Section 5.10.

13. The proposed development of Lot 69F for use as a single-family residence will not cause a diminution of value of Plaintiffs' Property, nor will it cause a harmful increase in storm water runoff, or otherwise cause damage to Plaintiffs' Property.

14. Due to existing drainage patterns on Plaintiffs' Property, the elevation of Plaintiffs' house and the existing grading of Plaintiffs' lot, it is not likely that water would enter Plaintiffs' basement, absent a crack or flaw in their foundation. It also is unlikely that stormwater will encroach on Plaintiffs' southern driveway even during a one-hundred year storm with the existing catch basins partially blocked.

15. Plaintiffs' claims that the construction of a single-family residence on Lot 69F will negatively impact them in terms of noise, [Note 5] light, [Note 6] air, open space and density of the neighborhood, [Note 7] and that the construction of a house will cause a harmful increase in traffic [Note 8] are either speculative or, at most, de minimis. In addition, Plaintiff will not suffer any particularized harm from any increase in traffic on Lake Street. [Note 9]

* * * * *

Plaintiffs Do Not Have Standing

Under G. L. c. 40A, § 17, only a "person aggrieved" has standing to challenge a decision by a zoning board of appeals. 81 Spooner Rd., LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012). A person aggrieved must suffer "some infringement of legal rights." Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996). Aggrievement requires more than "minimal or slightly appreciable harm," and the "right or interest asserted by the party claiming aggrievement must be one that G. L. c. 40A intended to protect." Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 121 (2011). [Note 10]

Under G. L. c. 40A, § 11, "abutters, owners of land directly opposite on any public or private street or way, and abutters to the abutters within three hundred feet of the property line of the petitioner," are entitled to notice of zoning board hearings and "enjoy a rebuttable presumption that they are 'persons aggrieved'" by a decision concerning another property. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. Here, there is no dispute that Plaintiffs, as "owners of land directly opposite on any public or private street or way" to Lot 69F, are "parties in interest" under G. L. c. 40A, § 11, and benefit from a rebuttable presumption that they have standing. 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 700; Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721.

"A defendant, however, can rebut a party's presumptive standing by showing that, as a matter of law, their claims of aggrievement, either in the complaint or during discovery, are not interests that [G. L. c. 40A] is intended to protect . . . . Alternatively, the defendant can rebut the presumption by coming forward with credible affirmative evidence that refutes the presumption, that is, evidence that warrant[s] a finding contrary to the presumed fact of aggrievement, or by showing that the plaintiff has no reasonable expectation of proving a cognizable harm." Picard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Westminster, 474 Mass. 570 , 573 (2016), quoting Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 33 (2006). A defendant may also rely on the plaintiff's lack of evidence in order to rebut a claimed basis for standing. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35 (stating a developer was not required to provide affidavits on each of the plaintiff's claimed aggrievements, but could rely on plaintiff's lack of evidence as to those claims, obtained through discovery).

If sufficiently rebutted, plaintiffs then must "'establish by direct facts and not speculative personal opinion that [their] injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community[.]'" 81 Spooner Road, LLC, 461 Mass. at 701, quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 32. [Note 11] The question is "whether plaintiffs have put forth credible evidence to show they will be injured or harmed by the proposed changes to an abutting property, not whether they will simply be 'impacted' by such changes." Kenner, 459 Mass. at 121. Credible evidence is

composed of both qualitative and quantitative components: "quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury," and "[q]ualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the board's action." Butler v. Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 441 (2005) (internal citations omitted). Conjecture and personal opinion are insufficient. Id. As discussed below, Plaintiffs' presumptive standing was rebutted at trial by Defendants and Plaintiffs did not thereafter establish any aggrievement.

Alleged Harm Due to Noise, Lighting, Increased Traffic, and Increased Density

Plaintiffs allege they are aggrieved by the Board's decision because the proposed development of Lot 69F will negatively impact their light, air, open space and density of the neighborhood, and will cause an increase in noise and traffic. Plaintiffs also allege the proposed development will negatively affect their property value and will direct harmful stormwater runoff onto their property.

Plaintiffs' allegations of harm from noise, lighting, traffic and overall density of the neighborhood amounts to speculation and conjecture. Defendants, relying on the testimony of Mr. Murchison, have demonstrated that any harm is, at most, de minimis, which cannot serve as a basis for standing. See Kenner, 459 Mass. at 124. Further, evidence offered by Plaintiffs in support of these alleged aggrievements failed to show how the alleged harms are "special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community." Kenner, 459 Mass. at 118. The

aggrievement must be particular to Plaintiffs themselves, and not merely to the community at large. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33. Mr. Murchison's testimony that he expects an increase in lighting, traffic and noise as a result of a new house being built across the street on a three-acre lot was insufficient to establish standing to challenge the Board's decision upholding the ZEO.

Plaintiffs also alleged harm due to overcrowding, or an increase in the density of the neighborhood. The proposed structure for Lot 69F, however, complies with all dimensional requirements of a residential zoning district, as well as with the three-acre minimum lot size, with the only possible exception being the issue of whether the "lot width at the building line" was interpreted correctly in accordance with the By-Laws. While this interpretation question was the issue tried on the merits (which this court does not reach in this decision), the effect of interpreting the By-Laws as urged by Plaintiffs would not render Lot 69F unbuildable, it would affect only the placement and size of the house that could be built. Plaintiffs cite several cases in support of the argument that density-based claims of harm can confer standing. This court does not take issue with the theoretical premise but the cases cited have significantly different factual contexts and largely present challenges to construction on undersized lots which have merged with adjacent lots in areas where "existing development is already more dense than the applicable zoning regulations allow." Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 296 (2008); see also, e.g., Mauri v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newton, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 336 , 340 (2013); Marhefka v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Sutton, 79 Mass. App. Ct. 515 , 519 (2011). While the

cases cited by Plaintiffs might allow, they certainly do not compel a ruling in this case that Plaintiff has established particularized harm to them by the proposed construction based on increased density. Based on Mr. Murchison's testimony, this court finds Plaintiffs simply do not want any construction on Lot 69F.

Diminution in Property Value

Plaintiffs allege a diminution in the value of their property as a result of the Defendants' proposed single-family residence. Diminution in value is not, in and of itself, an interest protected under G. L. c. 40A. Kenner, 459 Mass. at 123. It is a sufficient basis for standing only

where it derives from or relates to cognizable interests protected by the applicable zoning bylaws. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 3132.

Defendants presented testimony from Ms. McPherson, listing broker for Lot 69F, who works for Century 21 Commonwealth. Ms. McPherson opined that the addition of a single-family residence on Lot 69F would cause no diminution in the value of Plaintiffs' Property. To the contrary, she opined that a single-family residence is the "best and highest use" for the lot and the proposed house, complete with landscaping, would constitute an improvement in the neighborhood as opposed to its current condition as a vacant, cleared lot. Even taking into consideration Ms. McPherson's self-interest as the salesperson for Lot 69F, the court found this testimony sufficiently credible to rebut Plaintiffs' presumption of standing on the issue of diminution of value, shifting the burden to Plaintiffs to demonstrate through direct facts, and not speculation, that the development of Lot 69F will cause them a particular and personal harm resulting in diminution of value. Plaintiffs did not meet that challenge.

No expert testimony was proffered by Plaintiffs on the issue. Mr. Murchison testified that, in his opinion, Plaintiffs' Property is worth an estimated five million dollars. The court allowed his testimony as a lay owner of residential property and not as an expert witness. [Note 12] "A nonexpert owner of property may testify to its value upon the basis of 'his familiarity with the characteristics of the property, his knowledge or acquaintance with its uses, and his experience in dealing with it.'" Epstein v. Board of Appeal of Boston, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 752 , 759 (2010), quoting Winthrop Prods. Corp. v. Elroth Co., 331 Mass. 83 , 85 (1954). [Note 13] Plaintiffs failed to provide anything other than speculation and conjecture as to the perceived harm to their property value. Even if Plaintiffs had provided sufficient evidence of potential diminution of value, the decreased value was not tied to any particularized harm Plaintiffs proved they would suffer.

Storm Water Runoff

Defendants asserted a legal position that Plaintiffs' concerns about stormwater runoff is not an interest protected by the By-Laws, because stormwater is not listed in By-Laws Section 1.3 (see fact 11 above.) Defendants nonetheless produced sufficient evidence, primarily through

expert testimony from Michael C. Penney, a licensed professional engineer, to rebut Plaintiffs' claims of harm caused by increased stormwater runoff and potential for increased flooding.

Mr. Penney testified that, in his opinion, Plaintiffs will not suffer any harm due to stormwater runoff, or increased flooding. Based on his review of Lot 69F and the proposed development, he credibly testified that any stormwater runoff will not be significantly greater than any runoff that occurs with the lot in its current undeveloped state. He reviewed the topography of the lot and Lake Street, and included in his analysis the effect of nearby roadside ditches, catch basins and piping. As part of his analysis, he relied on a survey of Lake Street (see

Exhibit 59A) to identify the street's lowest points, and to locate three catch basins used in his calculations. This was needed to accurately calculate the volume of water the lowest spot on the survey, the northernmost catch basin could accommodate in a storm.

Mr. Penney's analysis also incorporated mitigation measures which are part of the proposed development, such as a foundation drain, infiltration swale, erosion control barrier and other measures aimed at reducing or directing runoff. He used his data to create different models. One model focused solely on Lot 69F, analyzing the peak flow and total volume of runoff from the lot in a natural, cleared or developed state, the potential for ponding on Lake Street, and the potential for ponding if a catch basin was fifty percent blocked. In recognition of the fact that lots other than Lot 69F may contribute runoff to Lake Street, Mr. Penney created a model for the potential runoff from all lots contributing stormwater to the lowest point in the street (called the "full contributory area"). Mr. Penney further explained his model was "conservative" because he used a category of soil less permeable than what is actually found at Lot 69F and enlarged the full contributory area to include more runoff water as a cautionary measure.

When analyzing the model limited to just Lot 69F, Mr. Penney determined that, while runoff from the lot in a developed state increased during a fifty year storm and a one hundred year storm, runoff was significantly less than it would have been from a cleared lot. Based on his models, Mr. Penney also testified that he found no scenario, whether Lot 69F was cleared or developed, in which runoff could crest Lake Street or reach Plaintiffs' southern driveway, even if the three catch basins shown on the Lake Street survey were partially obstructed during a one hundred year storm. To reach this conclusion, Mr. Penney modeled runoff for two, ten, twenty-five, fifty and one hundred year storms for each of the lot's potential states (natural, cleared or developed) to see whether runoff would reach Plaintiffs' Property. Given the existing drainage patterns and elevation of Plaintiffs' house, Mr. Penney found it was impossible for water to penetrate Plaintiffs' foundation, absent a crack or other flaw.

Mr. Penney's testimony provided credible evidence that Plaintiffs will not be aggrieved by increased runoff or flooding, and that their property likely will not suffer adverse effects from runoff as a result of the Board's Decision.

Plaintiffs attempted to rebut Mr. Penney's opinion by testimony from their expert, Paul Hutnak, a professional engineer and licensed soil evaluator, who stated that the peak rate of runoff from Lot 69F will increase by approximately ten to fifteen percent following construction of a single-family house on it. The court finds that, compared to the methodology and findings of Mr. Penney, the testimony of Mr. Hutnak was insufficient to establish Plaintiffs' standing based on harm from stormwater runoff. Mr. Penney analyzed runoff from Lot 69F in natural, cleared, and developed states, whereas Mr. Hutnak only compared the runoff from Lot 69F's natural state and its proposed developed state.

Plaintiffs also failed to sufficiently rebut Mr. Penney's testimony that runoff from the developed lot would be significantly less than runoff from a cleared lot, during a fifty or one hundred year storm due to the proposed mitigation. Mr. Hutnak agreed with Mr. Penney's assessment that a cleared lot would lead to more runoff than one in a natural state. He did not contradict Mr. Penney's claim that runoff from the full contributory area would not flow onto Plaintiffs' Property and cause damage. Mr. Hutnak's testimony omits any assertions or opinion that runoff from Lot 69F will cause actual damage to Plaintiff's Property. He did not challenge the majority of Mr. Penney's analyses and conclusions, and the court, as noted above, found Mr. Penney's opinion testimony well-supported and credible.

Conclusion

Having found that Plaintiffs are not aggrieved by the Decision, the court need not, and does not, reach the merits of their appeal. Plaintiffs lack standing, and the case will be dismissed.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

Q [y]ou concede that the noise you're referring to is only the noise associated with someone living on the property in a developed home on a day-to-day basis?

A: Well, I would say that would be the case, but I also would add construction noise to that.

Q: [A]fter a house is there, after a family is living there, the only noise you're referring to is noise associated with their living there and day-to-day activities?

A: And potential traffic . . . .

Q: [The] allegation of additional noise is simply a matter of speculation, is it not?

A No. I'd say it's a matter of knowledge and experience of having cars driving on the road and having people in houses and play music and such; it's experience.

Q: [W]hat you meant by lighting was simply the light that would come from the house on the lot and perhaps some outdoor lighting, correct?

A: Yes, that sounds right . . . . I've had experience living in houses over the course of my life where I can see the light coming into my house from their house[.]

Q: You have not engaged any engineer or other professional to do any form of study or analysis in an attempt to substantiate [beliefs of harm from air, open space and density]?

Q: You allege that increased traffic might result from the development of [L]ot 69F and thereby cause you harm, is that correct?

A: Yes . . . again, I have experienced traffic coming from increased development.

ROBERT MURCHISON and ALISON MURCHISON v. RICHARD NOVAK, et al., as they are MEMBERS of the TOWN OF SHERBORN ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS and MERRIANN M. PANARELLA and DAVID H. ERICHSEN.

ROBERT MURCHISON and ALISON MURCHISON v. RICHARD NOVAK, et al., as they are MEMBERS of the TOWN OF SHERBORN ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS and MERRIANN M. PANARELLA and DAVID H. ERICHSEN.