A lattice of private paths and ways overlays the island of Martha's Vineyard. Many of these paths and ways were made by the Native American inhabitants of the island; others were laid out by colonial-era settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries. Two hundred years ago, the paths and ways led to and from farms and hayfields. Today, many of them serve as the ways to private homes.

One of these private ways is Quenames Road in the town of Chilmark. The parties in this case, George and Robin S. Rivera (Riveras), Bridget Montgomery and Michael Spangler (Montgomery-Spangler), and Holladay Caery Handlin (Handlin), own lots bounded by Quenames Road. The Riveras have divided their lot into two through a plan approved as approval not required under the Subdivision Control Law. A dispute has arisen among the parties as to whether the Riveras have the right to install utilities under Quenames Road for the use of the second lot created by the plan. After a trial at which direct testimony of experts was filed by affidavit and the experts were cross-examined, I find that the Riveras have an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road by all their lots and, therefore, have the right to install utilities in Quenames Road under G.L. c. 187, § 5.

Procedural History

The Complaint in this action was filed by the Riveras on November 12, 2016, naming Montgomery-Spangler and Handlin as defendants (Defendants). The Defendants' Answer, Affirmative Defenses, and Jury Demand (Ans.) were filed on December 19, 2016. The Plaintiff's Answer to Counterclaim was filed on January 3, 2017. At a case management conference held on January 17, 2017, the Defendants waived the jury demand in their counterclaim and it was determined that the Defendants would file their counterclaim for trespass in the Superior Court and seek an interdepartmental assignment so that it could be heard with this action. The Defendants filed their, complaint for trespass in the Superior Court, see case No. 1774CV00021 (Superior Court Action), on April 19, 2017. I was authorized to sit as a Justice of the Superior Court Department to hear the trespass claims in the Superior Court Action on May 18, 2017.

The Plaintiffs' motion for Summary Judgment, Memorandum in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment, and Plaintiffs' Statement of Material Facts were filed on July 7, 2017. The Defendants' Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment and Cross- Motion for Summary Judgment, Memorandum of Law in Support of Defendants' Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment and Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, Defendants' Response to Plaintiffs' Statement of Material Facts and Defendants' Statement of Additional Material Facts (Defs.' Resp. to Pls.' SOF), and Defendants' List of Exhibits in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment and in Support of Defendants' Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment were filed on August 7, 2018. The Plaintiffs' Reply and Opposition to Defendants' Opposition and Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment, Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Response to Plaintiffs' Statement of Material Facts and Plaintiffs' Response to Defendants' Statement of Additional Facts, and Plaintiffs' Statement of Additional Material Facts in Response to Defendants' Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment were filed on August 21, 2017. The Defendants' Reply and Sur-Reply Memorandum and Defendants' Responses to Plaintiffs' Statement of Additional Material Facts were files on August 28, 2017. The motions for summary judgment were heard and taken under advisement on September 8, 2017.

At a telephone conference call held on September 26, 2017, the court instructed the parties to provide supplemental record and briefing and to decide whether the cross-motions for summary judgment should be treated as a case stated. At a telephone conference call held on October 16, 2017, the cross-motions for summary judgment were converted to a case stated pending a trial for the purposes of cross-examining each party's expert. The Memorandum on Plaintiffs' Supplemental Title Affidavit and Expert Report in Further Support of plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment, Second Affidavit of Douglas O. Dowling, PLS, and Second Supplemental Affidavit of Edward Rainen were file on January 12, 2018. The Defendants' Supplemental Brief in Support of Cross-motion for Summary Judgment was filed on March 21, 2018. The Joint Pre-trial Conference Memorandum was filed on March 30, 2018. A trial was held on April 11, 2018. The court reporter was sworn. Exhibits 1A and 1-9, with sub-exhibits, were admitted. Testimony was heard from Edward Rainen (Rainen), Kathleen O'Donnell (O'Donnell), and Douglas Dowling (Dowling), after which the parties rested. The Defendants' Post-Trial Brief was filed on June 12, 2018. The Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Memorandum was filed on June 13, 2018. The court heard closing arguments on June 19, 2018, and took the case under advisement. This Decision follows.

Facts

Based on the undisputed facts, the exhibits, the testimony at trial, and my assessment of credibility, I make the following findings of fact.

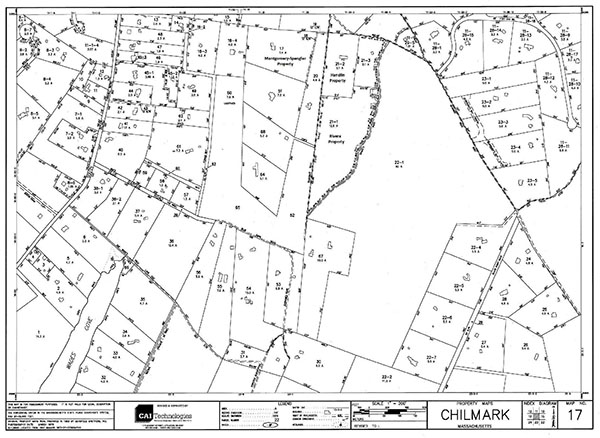

1. The Riveras own the property located at 88 Quenames Road, Chilmark, Massachusetts (Rivera Property), by deed dated October 21, 2004, and recorded with the Dukes County Registry of Deeds (registry) at Book 1022, Page1069. The Rivera Property is further identified as lot 21-1 on Chilmark Assessor's Map 17 (Assessor's Map), a copy of which is attached as Exhibit A. Defs.' Resp. to Pls.' SOF ¶ 1; Complaint Exh. D.

a. In 2004 the land purchased by the Riveras included lots 21-1 and 21-3, as shown on the Assessor's Map, which at that time were a single parcel. In 2005, by a plan endorsed as "Approval Under the Subdivision Control Law Not Required" (ANR endorsement) by the

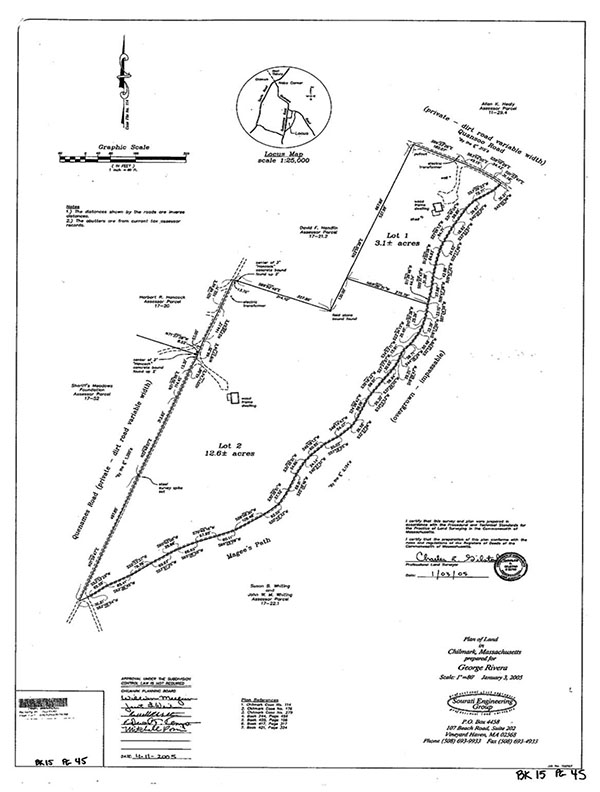

Chilmark Planning Board, the Riveras divided their property into the two lots shown on that plan entitled "Plan of Land in Chilmark, Massachusetts prepared for George Rivera," dated January 3, 2005, and recorded with the registry at Plan Book 15, Page 45 (2005 ANR Plan). The 2005 ANR Plan is attached as Exhibit B. Complaint ¶¶ 8 & Exh. C; Ans. ¶ 8.

b. After dividing their property, the Riveras sold the lot shown on the Assessor's Map as lot 21-3. Complaint ¶ 13; Ans. ¶ 13.

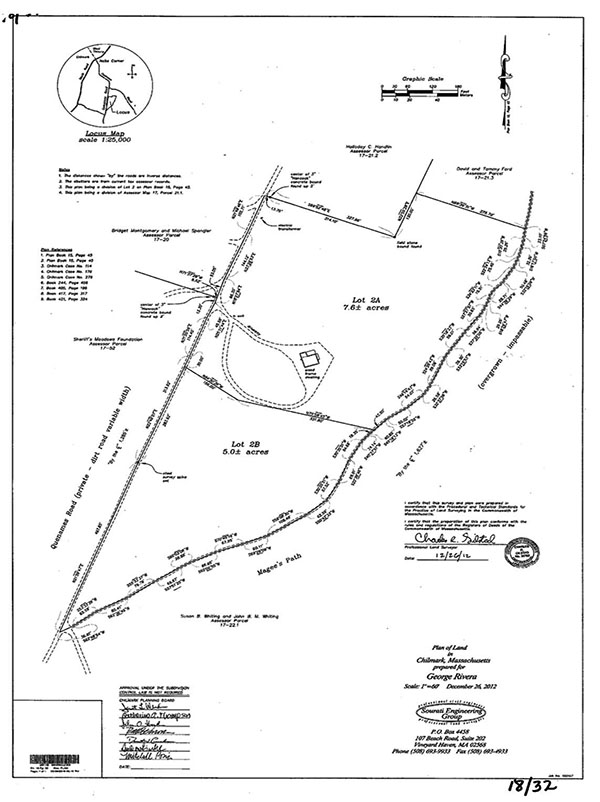

c. In 2013 the Riveras divided their remaining property as shown on another ANR plan, endorsed by the Chilmark Planning Board, entitled "Plan of Land in Chilmark, Massachusetts prepared for George Rivera," dated December 26, 2012, and recorded with the registry at Plan Book 18, Page 32 (2012 ANR Plan). The 2012 ANR Plan is attached as Exhibit C. Complaint ¶¶ 15-16 & Exh. E; Ans. ¶¶ 15-16.

2. Montgomery and Spangler own the property located at 73 Quenames Road, Chilmark, Massachusetts (Montgomery-Spangler Property), by deed dated December 5, 2003, and recorded with the registry at Book 981, page 196. The Montgomery-Spangler Property is further identified as lot 20 on the Assessors Map. Defs.' Resp. to Pls.' SOF ¶ 2.

3. Handlin owns the property located at the intersection of Quenames and Quansoo roads in Chilmark, Massachusetts, shown as lot 21-2 on the Assessors Map (Handlin Property), by deed dated February 18, 2010, and recorded with the registry at Book 1216, Page 879. Defs.' Resp. to Pls.' SOF ¶ 3.

4. The Rivera, Montgomery-Spangler, and Handlin Properties each abut Quenames Road located in Chilmark, Massachusetts, on the island of Martha's Vineyard. Exh 1A. Quenames Road is a private way. Exh. 2. [Note 1]

Martha's Vineyard, Chilmark, and a Place Called Quenames

5. In the mid-1600's Thomas Mayhew purchased Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Isles. Exh. 1, ¶ 22. Among these was a 1668 purchase of land on Martha's Vineyard from the Wompanoag, the Native American inhabitants of the island. The deed, dated June, 27, 1668, recites in relevant part:

This doth witness that I, Keteanummin Seachym of Takemmy, do hereby sell unto Thomas Mayhew of the Vineyard all that land that lyeth to the Eastward of Quanaimes, which Pemehannett and Kemasoome sold to the said Thomas Mayhew: I say I do hereby sell to the said Thomas Mayhew all the plain and the meadow, cornfields, woodlands, fish and whale only excepted, from Quansooway along by the Fresh Pond till it comes to the issuing of the Tyasquan: and from thence up to the bridge wch[sic] is at the path that comes from the mill: and so from the bridge along the school house path till it meets with the land sold the said Mayhew by the said Pemehannett and Kemesoom: So this land is bounded to the Westward by that which was pemehannett's: by the Sea on the South: by the Fresh Pond to the Eastward: and Northerly by Teeassquan River to the bridge: and then by the school house path till it meet with aforesaid land that was Pemehannetts

Exhs. 4, 4H.

6. Moving ahead approximately 150 years, Rainen testified that land in the area of Quenames and Quansoo Roads, encompassing what are today the Rivera, Montgomery-Spangler, and Handlin Properties, was, up until about 1826, owned entirely by a Jonathan Mayhew of Chilmark, Massachusetts. Tr. 171-173; Exh. 7, ¶ 18. After his death the property was left to his sons, Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) and Gilbert Mayhew. In 1826, the brothers divided the property by a deed dated April 29, 1826, and recorded in the registry at Book 22, Page 431(Partition Deed). Exh. 7A. The Partition Deed divided land belonging to Gilbert's and Jonathan (Jr.)'s deceased father along a division line. The Partition Deed in relevant part provided:

Which said tracts our Father Jonathan Mayhew late of said Chilmark [illegible] deceased gave unto us as [illegible] by his last Will & Testament. We the said Jonathan [and] Gilbert have agreed to make partition of the said tracts of land

do therefore make division thereof as follows viz., Beginning at a stake and stones land [illegible] by the land of William Clark and near to the cross paths so called being forty seven rods from Northernmost corner of the Homestead Lot, thence south twenty one degrees west or thereabouts one hundred and thirty five rods through the woods to a stake and stones, thence south seven degrees west fifty and one fourth rods to a stake and stones standing in the middle of the old field between the lands of said Clark [and] William Mayhew, thence south sixty three degrees east eighteen and a half rods to a stake and stones, thence south twenty degrees west eighty [and] a half rods to a stake and stones, thence south sixty degrees east sixteen rods until it comes to the middle of the Northmost end of the Corn House, thence southerly through the middle of the corn house, thence on a straight line to the middle of the dwelling house, thence southerly through the middle of said house on a straight line to a fence three and a half rods from said house, thence north fifty seven degrees west four rods and thirteen feet to a stake and stones in the southernmost corner of the house-yard, thence north thirty degrees west four and one fourth rods to a stake and stones standing in the northwestermost corner of said yard, thence north fifty six degrees west ten and a half rods to a stake and stones, thence south thirty degrees west fifteen and a half rods to a stake and stones, thence north fifty-nine degrees west four and a half rods till it comes to the barn, thence easterly by said barn five feet and ten inches until it comes to the easternmost bay, thence by the southwesterly side of said bay till it comes to the middle of said barn, thence south easterly in the middle of said barn eighteen feet and eight inches till it comes to the westernmost bay, thence Northwesterly twelve feet or until it comes to the northerly side of said barn, thence south thirty three degrees west three and one fourth rods to a stake and stones, thence south sixty three degrees east seven rods and two feet crossing the middle of the well to a stake and stones, thence south twenty degrees west one hundred and forty one rods to a stake and stones, thence south twenty degrees west till it comes to the Sea.

And I the said Jonathan do hereby

convey

to the said Gilbert

all the land lying to the northward [and] westward of said division line, together with all the buildings, parts of buildings thereon standing, and all other appurtenances thereunto belonging.

And I the said Jonathan

convey

to the said Gilbert

the parts of the following tracts of land described and bounded as follows, the gore of land lying northerly of the cross path aforesaid and within the angles of the Quenames, Quansue [and] Bethias roads so called. Also the southwesternmost half of the heater lot so called, the division line to begin at a black oak tree marked M.[illegible] standing on the south easterly side of said Quenames road from thence Northwesterly on a straight line to a stone set in a stump formerly known as the Rabbit tree.Also the southwesterly half of the Bethias Lot so called, the division line beginning by the road leading from Chilmark to Tisbury at a stake and stones standing nine and a half rods from the southeasterly corner of said Clarks land being on the southeasterly side of said road, thence southeasterly sixty seven rods till it comes to a stake and stone standing on an old ditch, thence southerly by said ditch to said Clarks land, thence southwesterly by the last mentioned land till it comes to the first mentioned corner.

Also the southwesterly part of the old wood lot laying to the Northward of the last mentioned land, the division line beginning as follows at the southeasterly corner of William Mayhews land by the ridge-hill[illegible] road so called, thence north forty five degrees east thirteen and three fourths rods to a stake and stones standing on the south side of the last mentioned road, thence south forty seven degrees east till it comes to the said Chilmark road, thence southwesterly by said road four and one fourth rods to the said William Mayhews land, thence southwesterly by the last mentioned land till it comes to the [][illegible] on ridge hill

And I the said Gilbert do hereby setoff make over covey and confirm to the said Jonathan

all the land laying to the southward and eastward of the first mentioned division line together with all the buildings and parts of buildings thereon standing, with the exception of having access[illegible] to the well of water. Pens and the barn also the cellar and the garret. And the said Gilbert do hereby further set off

to the said Jonathan

the parts of the following tracts of land described and bounded as follows, the northeasterly half of the Heater lot, so called, also the southeasterly half of the Bethia lot so called, Also the North easterly part of the old wood lot so called.

Exh. 7A. The effect of the Partition Deed was that Gilbert took title to the land to the west of the division line described in the Partition Deed (division line), and Jonathan (Jr.) took title to the land to the east of the division line.

7. Shortly after the Mayhew brothers partitioned their fathers' land, Jonathan (Jr.) died. In 1827, Almira Mayhew, the administratrix of his estate, conveyed certain parcels of land belonging to the late Jonathan (Jr.) to Samuel Hancock by a deed dated June 4, 1827, and recorded in the registry on January 17, 1828, at Book 23, Page 138 (1827 Deed). The 1827 Deed in relevant part provides:

I do hereby

convey

unto [illegible] the said Samuel Hancock

[a] certain parcel of woodland situate in Chilmark known by the name Baylies Swamp Lot, and bounded as follows viz. on the West by ridge hill path, on the south by land of Gilbert Mayhew, on the East by Chilmark or County Road, and on the North by land of the heard of Wm. Mayhew late deceased.

Also one other tract of woodland situate in Chilmark near Wm. Mayhews dwelling house, and bounded as follows, Beginning at a stake and stones set where the cross path so called intersects with Quenames Road at right angles thence North seventy nine degrees east by said cross path thirty seven and a half rods, thence south forty two degrees West ten rods by Magees path, thence South eighteen degrees west, ten rods by said path, thence South sixteen rods by said path, thence south twenty four degrees west thirteen and a half rods by said path, thence south seventy six degrees west thirty two and a half rods through the woods to Quenames Road, thence North twelve degree East forty seven [and] a half rods by said Quenames road to the first mentioned bound. Containing ten acres.

Exh. 7B.

8. By a similar and somewhat repetitive deed dated June 17, 1833, and recorded in the registry on June 27, 1833, at Book 24, Page 440 (1833 Deed), Almira Mayhew conveyed additional lands to Samuel Hancock. The 1833 Deed conveyed:

Certain tracts of land situate in said Chilmark at a place called Quenames viz. One tract beginning as to bounds at the Northwest corner of the cleared land owned by my late husband Rev. Jonathan Mayhew, thence easterly by the fence dividing the said cleared land from the wood land, to the land of William Mayhew Junior thence southerly by said Williams land ill it comes to the head of Quenames cove, so called, thence westerly by a fence standing on a ditch till it comes to land of said Samuel Hancock, thence northerly by said Hancocks land to the first mentioned corner with the buildings standing thereon. (Excepting the West Corner [and] the yard in front of it)

Also one tract of wood land called Baileys Swamp Lot reference being had to deed given by one as Administratrix to the estate of Rev. Jonathan Mayhew deceased to said Hancock.

Also, one other tract of wood land, bounded and described as follows viz. beginning at Quenames Road, where Bethias road intersects said Quenames road at right angles, thence East Southerly by said Bethias road until it comes to Magees path, thence southerly and westerly by said Magees path to Quenames road; thence northerly by said Quenames road to the first mentioned place of beginning.

Also, one other tract of beach [and] meadow at Quenames neck so called, and bounded as follows viz. beginning at a stake [and] stones one yard south from the East end of the [illegible] water fence, thence Westerly on a straight line by said fence to the meadow of said Hancock [and] Jonathan Mayhew Junior, thence Southerly by said Hancocks [and] Mayhews land to the Ocean, thence East by said Ocean to beach [and] meadow of the heirs of Joseph Chase late deceased, thence, Northerly by said heirs land, [and] the pond to the first mentioned bound.

Exh. 7C.

9. After Samuel Hancock died, his sons Freeman and Russell Hancock partitioned land left to them by their late father, by a deed dated January 30, 1873, and recorded in the registry at Book 56, Page 163, on December 18, 1873 (1873 Deed). The 1873 Deed provided in relevant part:

"That we Freeman Hancock and Russell Hancock both of Chilmark, in the County of Dukes county and State of Massachusetts, are equally invested in a number of tracts of land situated in said Chilmark, at a place called Quenames and thereabouts which our father Samuel J. Hancock late of Chilmark, deceased, gave unto us as [illegible] by his last will and testament.

We, the said Freeman and Russell have agreed to make division of all said tracts of land which lie to the north of the lower meadow fence as it now stands, said fence beginning by the Quenames Cove about fifty rods from the east side of the canal, and Joseph Nickersons dwelling house bearing west thirtysix degrees north thence directly towards said Nickersons house twenty[three illegible] rods, thence west thirteen degrees and on a straight line until it comes to the Chilmark Pond about twenty-eight rods form the west end of the canal.

That each of us may hold

[illegible] make division thereof as follows: Beginning at said lower meadow fence about halfway between Chilmark Pond and Quenames Cove on the former division line between Jonathan and Gilbert Mayhew thence north twenty four degrees east twenty eight rods by said line, thence north thirty degrees east and[sic?] said old line and on a straight line with it to land of Russell Hancock . And I the said Freeman do hereby setoff make over convey and confirm unto the said Russell his heirs executors, administrators, and assigns forever, all that tract of land lying to the eastward of the above mentioned division line. Said tract of land extending from the lower meadow fence to land of said Freeman Hancock to the north of Russell Hancocks land.

Also the eastern part of the North Field, so called, the division line [illegible] commence at [illegible] the west corner of land of Ann J. Hancock thence westerly on a straight line with the south side of the said Ann J. Hancocks land twenty one[illegible] and three fourths rods to an old ridge. Thence Northerly by said old ridge fifty and one half rods to a stake and stones standing by the edge of the woods. Thence Easterly by the edge of the woods on a straight line to land of Samuel L. Allen near his dwelling house. Thence Southerly by said Allens land and land of Ann J. Hancock to the place of beginning.

Also parts of the following tract of woodland bounded and described as follows, the north part of the tract lying to the west and adjoining the Quenames road, the division line to begin at a stake and stones on the west side of said Quenames Road, sixty rods to the southward of the crossroad, thence West Northwest eleven and three fourth rods to land of David Nickerson.

Also, the south and east parts of the Heater lot lying to the east and adjoining said Quenames road the division line to begin at a stake and stones on the east side of the said Quenames Road, forty one rods and eight links to the southward of the cross road thence east fourteen degrees south nineteen and one half rods to a stake and stones, thence northerly forty rods to a steak and stones by the side of the cross road nineteen and one half rods [illegible] the Quenames Road.

Also the east part of the Nabs Corner lot, so called, the division line to begin at the Northeast part of said lot near Nabs Corner, thence southerly on a straight line through said lot to a stake and stones by land of [illegible], said bounds being twenty rods from the highway on the west, and twenty four rods from land of [illegible] Adams on the east

And I, the said Russell do hereby set off make over, convey and confirm unto said Freeman his heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns forever, all that tract of land lying to the westward of the two just mentioned divisions lines, said tract of land extending from the lower meadow fence to the woods at the North abrest[sic] of the dwelling house of Samuel L. Allen.

Also all the south part of the wood lot to the west of Quenames road including the orchard and the woods. Also the northwest part of [the] Heater lot lying to the east of Quenames Road. Also the western part of the Nabs Corner lot.

Exh. 7G.

10. Rainen testified that the first course of the division line as described in the Partition Deed began at the northwest corner of what is today the Montgomery-Spangler Property and ran southwesterly along the westerly lot line following that course south until it intersected with Blue Barque Road. Tr. 162-163; Exh. 7.

11. Dowling testified that he did a significant amount of survey work in the area of Quenames Road in the 1980's during which he located the division line. Dowling testified that the division line begins approximately 118 feet west of the "Cross Path"which point is the north west corner of the Montgomery-Spangler Property"and it goes slightly south, about 20 degrees southwest, to the Three Point Rock, which is on the north side of Blue Barque Road." Tr. 194-197; Exhs. 1A; 8A; 8B.

12. I credit Rainen's and Dowling's testimony with respect to the location of the division line and find that the division line runs along the rear, i.e. the westerly, lot line of the Montgomery-Spangler Property, beginning at its northwest corner and running southwesterly along the rear lot line, maintaining that bearing until it intersects with Blue Barque Road. The substance of the division line can be seen as the westerly lot lines of lots 20 and 52 on the Assessor's map.

13. O'Donnell stated in her Supplemental Expert Report, marked as Exhibit 9, that "the location of Quenames Road at the time of the [Partition Deed] cannot be shown to be in the same location as at present, or when the Riveras purchased their property in 2004. The [Partition Deed] lacks clarity and sufficient specificity to determine the physical location of Quenames Road at the time of the [Partition Deed]." Tr. 96-97; Exh. 9.

14. Rainen testified as to his opinion of O'Donnell's statement regarding the location of Quenames Road in 1827, as follows:

Roadways prior to the 20th century did not get moved, because there was no heavy equipment to recreate them. The only time that a roadway would be moved is if a tree fell in a heavy storm and people had to walk around it. Roadways were created by humans in an area that enabled humans to travel with the least amount of difficulty, which is why Native Americans chose certain pathways that stayed out of the swamp and tried not to climb hills if they could avoid it; and that's why the same trodden path

was trodden upon for thousands of years, because it took them to places that enabled them to fish or hunt or do whatever they did. So the idea that Quenames Road would have been physically moved between the pre-Columbian period and 1827 and now 2018 does not make good sense to me.

Tr. 158-159.

15. Dowling's 1980's surveys in the area of Quenames Road identify it as an ancient way of variable width. Exh. 3. Dowling testified that in determining that the present location of Quenames Road was the location of an "ancient way" he relied on physical evidence, deed references, and maps from the time period. Tr. 185-186.

16. The roads now known as Quenames Road and Quansoo Road appear on various maps of the area from 1850, 1858, and 1891, and are shown in their current locations in the Google Maps image which is in evidence as Exhibit 5A. Exhs. 2R; 4B; 4D; 4E; 5A.

17. Having reviewed the 1827, 1833, and 1873 Deeds and the maps of the area from 1850, 1858, and 1891, and having considered the testimony of O'Donnell, Rainen, and Dowling, I find that Quenames Road is in the same location on the ground today as it was at the time of the 1827 Deed when it was first used as a bound in that conveyance to Samuel Hancock.

18. I credit Rainen's testimony and find that at the time of his death Jonathan Mayhew (Sr.) owned all of the land on both sides of Quenames Road. I further find that by virtue of taking title to all the land south and east of the division line in the Partition Deed, Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) in 1827 owned all of the land on each side of Quenames Road including what are now the Rivera, Montgomery-Spangler, and Handlin Properties.

19. I find that the tract of woodland bounded to the west by Quenames Road described in both the 1827 and 1833 Deed is that land which is now the Rivera Property, the Handlin Property, and another parcel not owned by any party to this action. This tract of woodland is what is shown as lots 21-1, 21-2, and 21-3 on the Assessor's Map.

20. I further find that the two tracts of land granted to Russell Hancock in the1873 Deed described as:

Also parts of the following tract of woodland bounded and described as follows, the north part of the tract lying to the west and adjoining the Quenames road, the division line to begin at a stake and stones on the west side of said Quenames Road, sixty rods to the southward of the crossroad, thence West Northwest eleven and three fourth rods to land of David Nickerson.

Also, the south and east parts of the Heater lot lying to the east and adjoining said Quenames road the division line to begin at a stake and stones on the east side of the said Quenames Road, forty one rods and eight links to the southward of the cross road thence east fourteen degrees south nineteen and one half rods to a stake and stones, thence northerly forty rods to a steak and stones by the side of the cross road nineteen and one half rods [illegible] the Quenames Road,

are the Montgomery-Spangler and Handlin Properties respectively.

21. I further find that based on the contents of the 1873 Deed, Samuel Hancock, by transfers not documented in the record before this court, acquired much of the land to which Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) took title in the Partition Deed. Finally, I find that the parcel of land which is now the Rivera Property was not described or conveyed by the 1873 Deed and was thus either conveyed by Samuel Hancock prior to his death or was otherwise devised but not to Freeman and Russell Hancock jointly.

22. The subsequent disposition of parcels of land owned by Samuel Hancock by virtue of the 1827 and 1833 Deeds and by Freeman and Russell Hancock by virtue of the 1873 Deed is not clearly documented in the registry records that are before the court. It appears that each of the Rivera, Montgomery-Spangler, and Handlin Properties at various times passed on from their former owners by marriage or devise, the probate records for which are not before the court. Having reviewed the 1827, 1833, and 1873 Deeds and those more recent documents which evidence the transfer of the subject parcels, to the extent that it is relevant to my inquiry, I detail the post-1873 title histories of the parties as follows.

Rivera Chain of Title

23. As discussed, the 1827 and 1833 Deeds conveyed to Samuel Hancock land along the eastern border of Quenames Road that included what is now the Rivera Property, with Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) retaining the property along the western bound of Quenames Road, including what is now the Montgomery-Spangler Property. Generally it appears that after Samuel Hancock took title to the parcel which includes the now Rivera Property by the 1827 and 1833 Deeds, title to the Rivera Property alone eventually passed by marriage or devise to an Esther R. Hancock. Exh. 1A.

24. In 2001, Herbert R. Hancock took title to the Rivera Property by a release deed from Fleet National Bank in its individual corporate capacity, as Trustee of the Trust of Esther R. Hancock, and as co-executor along with Charles F. Phillips, Jr., Marjorie H. Phillips, and Ruth

H. Gilmour of the estate of Esther R. Hancock, dated February 20, 2001, and recorded with the registry at Book 825, Page 415 (2001 Deed). The 2001 Deed provides that Esther R. Hancock's record title to the Rivera Property was acquired through the 1827 Deed from Almira Mayhew to Samuel Hancock. Exh. 1A. [Note 2]

25. The Riveras took title to the Rivera Property in 2004, by a deed from Wilma G. Hancock, a/k/a Billie Hancock, individually and as Executrix of the Will of Herbert R. Hancock, dated October 21, 2004, and recorded in the registry at Book at 1022, Page 1089. Exh. 1A.

Montgomery-Spangler Chain of Title

26. Generally it appears that Russell Hancock took title to the Montgomery-Spangler Property though the 1873 Deed and that ownership of that lot passed to a Herbert C. Hancock, and then by devise to a Hariph C. Hancock, upon whose death it passed by devise to a Marion C. Hancock. Exh. 2H.

27. The Montgomery-Spangler property was conveyed to Herbert R. Hancock and Jean F. Hancock in 1967, by a deed from Marion C. Hancock dated September 25, 1967, and recorded in the registry at Book 268, Page 299. Exh. 1A (Marion Hancock Deed). The deed conveys "right title and interest to those parcels of land with all buildings thereon, situated in said Chilmark, at a place called Quenames, which was set off to Russell Hancock in a division deed between Freeman Hancock and Russell Hancock dated January 30, 1873, and recorded with Dukes County Registry of Deeds in Book 56 Page 163." Exh. 1A. The 2001 Deed to Herbert R. Hancock makes reference to the Marion Hancock Deed and purports to release title to Lot 20 on the Assessor's Map, which is the Montgomery-Spangler Property. Exh. 1A. Whether the Montgomery-Spangler Property was properly included in that release deed is of no consequence as Herbert R. Hancock's title to that property at that time is not disputed or dispositive.

28. Montgomery and Spangler took title to the Montgomery-Spangler Property in 2003, by a deed from Wilma G. Hancock, individually and as executrix of the will of Herbert R. Hancock, dated December 5, 2003, and recorded in the registry at Book 981, Page 196. Exh. 1A.

Handlin Chain of Title

29. Generally, it appears that through marriage or devise a Priscilla Hancock acquired title to the Handlin Property from Russell Hancock, or his successors, who took title to it in the 1873 Deed. The Handlin deed, discussed infra, suggests that the Handlin Property was left to the First Congregational Church of West Tisbury upon her death. Exh 1A.

30. Handlin first took title to the Handlin Property by a deed from the First Congregational Church of West Tisbury (the Church) to David F. Handlin and Holladay C. Handlin, dated January 27, 1984, and recorded with the registry in Book 411, Page 733. The deed provides that the Church's record title is from "the Estate of Priscilla Hancock Docket D B 5471 Dukes County Probate Records." Exh. 1A.

Discussion

The ultimate issue in this case is whether the Riveras have the right to lay utilities in Quenames Road. The Riveras seek to install electric utility lines in Quenames Road to supply electricity to the lot identified as 2B on the 2012 ANR Plan. The Riveras argue that such rights arise under G.L. c. 187, § 5 (Chapter 187), which grants the right to lay utilities in a private way to owners of real estate abutting a way who have deeded rights of ingress and egress on such way. Id. To determine the applicability of Chapter 187 to the Rivera Property it is first necessary to establish what rights the Riveras have in Quenames Road and under what circumstances they arise. The Riveras argue that they have the right to use Quenames Road for ingress and egress either by an easement by estoppel or by an implied easement.

Easement by Estoppel

There are two circumstances in which Massachusetts recognizes the creation of an easement in a way by estoppel. Patel v. Planning Bd. of North Andover, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 477 , 480 (1989). First, "'when a grantor conveys land bounded on a street or way, he and those claiming under him are estopped to deny the existence of such street or way, and the right thus acquired by the grantee (an easement of way) is not only coextensive with the land conveyed, but embraces the entire length of the way, as it is then laid out or clearly indicated and prescribed.'" Murphy v. Mart Realty of Brockton, Inc., 348 Mass. 675 , 677-678 (1965), quoting Casella v. Sneirson, 325 Mass. 85 , 89 (1949). The second arises when land is conveyed according to a recorded plan. Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 755 (1945). Under this category, when a grantor conveys land located on a street according to a recorded plan on which the street is shown, the grantor and those claiming under the grantor are "estopped to deny the existence of the street for the entire distance as shown on the plan." Id. "It is well settled that an easement created by estoppel, under either set of circumstances, estops the grantors and their successors in title from denying the existence of an easement

However, the doctrine of easement by estoppel in this commonwealth has not been expanded to estop the grantees and their successors in title from denying the existence of an easement." Waldron v. Tofino Assocs., Inc., 20 LCR 480 , 485 (2012), citing Patel, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 482.

Prior to his death, Jonathan Mayhew (Sr.) owned all of the land on either side of Quenames road including that land which is now the Rivera, Montgomery-Spangler, and Handlin Properties. In 1826, Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) took title to all of his father's land east of the division line described in the Partition Deed. This included all of the relevant land on either side of Quenames Road. For the purposes of this analysis, Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) is the common grantor of the parties' properties as it was under his ownership that the parcels of land along Quenames Road were first conveyed. In 1827, Almira Mayhew as administratrix of the estate of Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.) conveyed a tract of woodland to Samuel Hancock, the westerly bound of which was described as "North twelve degrees East forty seven [and] a half rods by said Quenames Road" to "a stake and stones set where the cross path so called intersects with Quenames Road at right angles." Exh. 7B. In other words, the conveyed property was '"bounded on a street or way.'" Murphy, 348 Mass. at 677, quoting Casella, 325 Mass. at 89. By this conveyance, Samuel Hancock, as predecessor in title to the Handlin and Rivera Properties had an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road. As the Montgomery-Spangler Property had not yet been conveyed, Montgomery and Spangler today sit in the position of successors to the common grantor Jonathan Mayhew (Jr.). Montgomery and Spangler are therefore estopped from denying that the Riveras have an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road. As the larger parcel of woodland has the benefit of an easement by estoppel to use Quenames Road, that it was subsequently divided does not change the relative positions of Handlin or the Riveras. They are each successors to the granteeSamuel Hancockand are each benefitted with an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road.

The 1873 Deed is also evidence that the Rivera Property has the benefit of an easement by estoppel to use Quenames Road. Because the Rivera and Handlin Properties were conveyed to Samuel Hancock in 1827 and the Montgomery-Spangler Property was included in the devise to his sons at the time of his death, it is likely that at some point between 1827 and 1873, Samuel Hancock owned all of the properties that are the subject of this action. To the extent that Samuel Hancock could be regarded as a common grantor for the purposes of an easement by estoppel, the absence of the Rivera Property from the 1873 Deed indicates that to whomever that title passed, it did so prior to January 30, 1873, when the Hancock brothers divided their inheritance. In this situation, the Riveras are successors to the granteewhoever it wasof the earlier conveyance or transfer, and Montgomery, Spangler, and Handlin are in the position of successors to Samuel Hancock the common grantor. Under either the 1827 Deed or the 1873 Deed, the Riveras have an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road and the Montgomery, Spangler, and Handlin are estopped to deny its existence. [Note 3] As I have found that the Riveras have an easement by estoppel, I need not consider the merits of their argument that in the alternative they have an implied easement for the use of Quenames Road. [Note 4]

Applicability of G.L. c. 187, § 5

The Riveras have an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road for ingress and egress. They argue that under Chapter 187, they also have the right to lay utilities in the road.

Chapter 187 provides in relevant part:

The owner or owners of real estate abutting on a private way who have by deed existing rights of ingress and egress upon such way or other private ways shall have the right by implication to place, install or construct in, on, along, under and upon said private way or other private ways pipes, conduits, manholes and other appurtenances necessary for the transmission of gas, electricity, telephone, water and sewer service, provided such facilities do not unreasonably obstruct said private way or other private ways, and provided that such use of the private way or other private ways does not interfere with or be inconsistent with the existing use by others of such way or other private ways; and, provided further, that such placement, installation, or construction is done in accordance with regulations, plans and practices of the utility company which is to provide the gas, electricity, or telephone service, and the appropriate cities, towns, districts, or water companies which provide the water service.

G.L. c. 187, § 5. Easements for the use of a way arising by implication, estoppel, or necessity are deeded rights for the purposes of Chapter 187 and confer on a property owner the right to lay utilities in an abutting way. Lane v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Falmouth, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 434 , 437-439 (2006); Adams v. Planning Bd. of Westwood, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 391-392 (2005); c.f. Cumbie v. Goldsmith, 387 Mass. 409 , 411-412 n.8 (1982) (easement by prescription is limited to the uses that created it and does not authorize the holder to lay utilities under G.L. c. 187, § 5). The Riveras therefore have the right to lay utilities in Quenames Road pursuant to Chapter 187.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons judgment will enter declaring that the Rivera Property is benefitted by an easement by estoppel for the use of Quenames Road, that pursuant to G.L. c. 187, § 5 the Riveras have the right to lay utilities in Quenames Road, and dismissing the Defendants' claims for trespass.

Judgment accordingly.

GEORGE RIVERA and ROBIN S. RIVERA v. BRIDGET MONTGOMERY, MICHAEL SPANGLER, and HOLLADAY CAREY HANDLIN.

GEORGE RIVERA and ROBIN S. RIVERA v. BRIDGET MONTGOMERY, MICHAEL SPANGLER, and HOLLADAY CAREY HANDLIN.