The question presented in these consolidated actions, by a motion and cross-motions for partial summary judgment, is whether a protest petition signed by landowners opposed to the rezoning of land in the Newtonville neighborhood of Newton, (the "Village") comprised ownership of the requisite twenty percent of land required to trigger an increased quantum of vote to adopt a zoning amendment under G. L. c. 40A, § 5. This controversy arises out of two decisions by the Newton City Council (the "City Council") approving a zoning amendment to rezone land in the Village owned by the non-municipal defendants and granting the defendants a special permit/site plan approval for their proposed development of the land. On October 31, 2017, the court held a hearing on the parties' motion and cross-motions for partial summary judgment. The sole issue, apparently one of first impression, was whether the plaintiffs' protest petition met the statutory requirements of G. L. c. 40A, § 5, so as to trigger an increase in the vote of the City Council necessary to pass the zoning amendment from two-thirds to threefourths.

For the reasons stated below, the defendants' motion for partial summary judgment is ALLOWED, and the plaintiffs' cross-motions for partial summary judgment are DENIED.

FACTS

The material undisputed facts pertinent to these motions for partial summary judgment are as follows:

1. The Village is located within the city ofNewton (the "City").

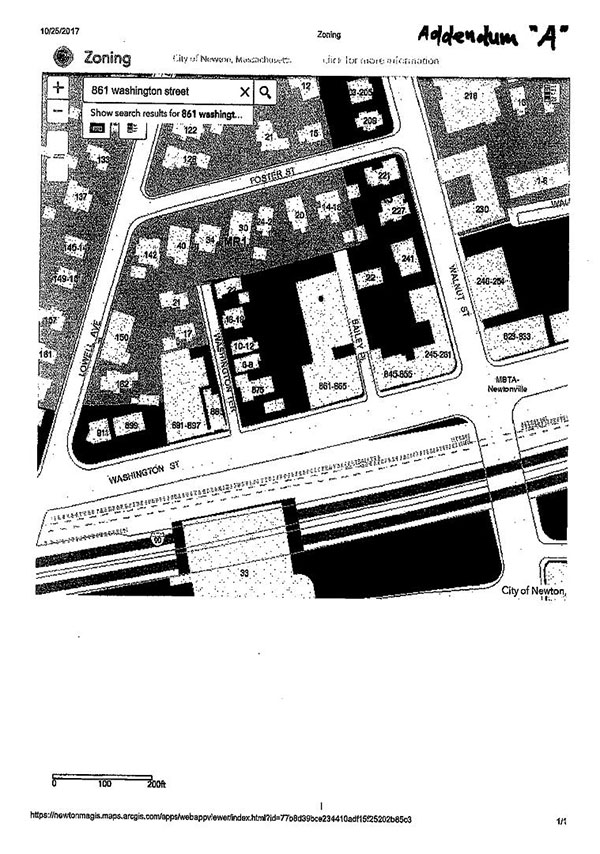

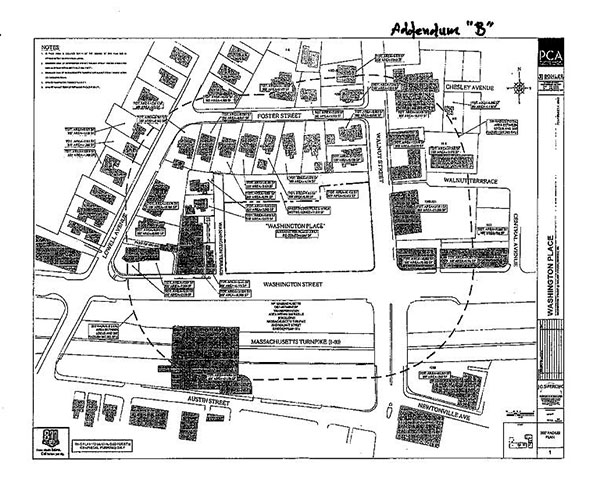

2. Mark Newtonville, LLC and Mark Lolich, LLC (collectively, the "Developer") own contiguous land located in the Village at 22 Washington Terrace, 16-18 Washington Terrace, 10-12 Washington Terrace, 6-8 Washington Terrace, 875 Washington Street, 869 Washington Street, 867 Washington Street, 861-865 Washington Street, 857-859 Washington Street, 845-855 Washington Street, 245-261 Walnut Street (also known as 835-843 Washington Street), 241 Walnut Street, Bailey Place, 22 Bailey Place, 14-18 Bailey Place, and an unnumbered lot on Bailey Place (collectively, the "Developer's Land"). [Note 1] See Addendum "A," infra.

3. On May 9, 2016, the Developer filed an application for a Special Permit/Site Plan Approval (the "First Application") for a mixed use retail and residential development on the Developer's Land (the "Project"). [Note 2] At the time of the First Application the various parcels comprising the Developer's Land were zoned either Business 1, Business 2, or Public Use, and the Developer simultaneously requested that the entirety of the Developer's Land be rezoned to Mixed Use 4 ("MU4"). [Note 3]

4. On August 12, 2016, landowners in the Village submitted a written protest (the "First Protest Petition") to the city clerk pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 5, opposing the Developer's rezoning request. [Note 4]

5. There are twenty-four members on the City Council, triggering the three-fourths vote requirement for a zoning amendment if the owners of twenty percent or more of the "area of land immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet" from the land to be rezoned file a petition in compliance with G. L. c. 40A, § 5, fifth para. (the "protest provision").

6. On January 11, 2017, the City of Newton Law Department ("Law Department") issued an interoffice memorandum to the City Council's Land Use Committee providing guidance as to how it would interpret the protest provision and concluded that only owners of land directly abutting the Developer's Land were eligible to protest. [Note 5] Applying its interpretation, the Law Department determined that landowners owning 84% of the area of land immediately adjacent to and within three hundred feet of the Developer's Land signed the First Protest Petition, thus requiring a three-fourths vote by the City Council to rezone the Developer's Land. [Note 6]

7. On February 22, 2017, the Developer submitted a request to withdraw both the request for rezoning and the First Application, without prejudice. The City Council approved the request to withdraw on April 3, 2017.

8. On April 4, 2017, the Developer refiled its Special Permit/Site Plan Approval application (the "Second Application") for the Project. With the Second Application, the Developer again submitted a rezoning request, but only to rezone 92,907 square feet of the Developer's Land to MU4 (the "Rezoned Area"). A 31,049 square foot section of the Developer's Land to the north of the Rezoned Area and separating the Rezoned Area from the northerly abutting properties would remain zoned "Business 2" (the "B2 Area").

9. On May 25, 2017, a number of landowners in the Village filed another protest petition (the "Second Protest Petition") with the city clerk pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 5, opposing the Developer's rezoning request as submitted in conjunction with the Second Application.

10. Plaintiffs Ellen Fitzpatrick of 20 Foster Street, Mari Wilson and John L. Wilson of 30 Foster Street, Bette A. White of 14 Foster Street, Robert H. Smith and Elizabeth B. Smith of 40 Foster Street, William R. Koss and Francesca Koss of 142 Lowell Ave., and Meghan Smith of 34 Foster Street (collectively, the "Foster Street plaintiffs") signed the Second Protest Petition. [Note 7]

11. Because the Developer now excluded the B2 Area from the area to be rezoned, a change from what had been requested with the first rezoning request, the Foster Street plaintiffs, whose land directly abutted the land as originally proposed to be rezoned, no longer owned land directly abutting the proposed Rezoned Area as requested in conjunction with the Second Application. Of the Foster Street plaintiffs, Fitzpatrick, White, Meghan Smith, and Mari Wilson and John L. Wilson own land that directly abuts the B2 Area, which is owned by the Developer, but which is no longer proposed to be part of the land to be rezoned.

12. On May 26, 2017, the Law Department issued a memorandum to the City Council's Land Use Committee, determining that the Second Protest Petition failed to trigger the requirement of a three-fourths vote to adopt the proposed zoning amendment, because none of the signatories to the Second Protest Petition owned land immediately adjacent to the Rezoned Area. [Note 8]

13. On June 19, 2017, plaintiff Patrick J. Slattery, Trustee of P&K Realty Trust II, owner of land at 221 Walnut Street and 227 Walnut Street, joined the Second Protest Petition. [Note 9] Slattery's land at 227 Walnut Street also directly abuts the B2 Area but does not abut the Rezoned Area as requested in conjunction with the Second Application.

14. None of the signers of the Second Protest Petition owns land that abuts the Rezoned Area, as proposed to be rezoned in conjunction with the Second Application.

15. The area of land extending three hundred feet from the Rezoned Area, as proposed to be rezoned in conjunction with the Second Application, and which is owned by the signers of the Second Protest Petition, is less than twenty percent of the total area of the land extending three hundred feet from the Rezoned Area.

16. On June 19, 2017, the City Council voted to approve the zoning amendment as requested in conjunction with the Second Application, in a vote of 16 yeas, 7 nays, and 1 absent. This was a margin meeting the two-thirds requirement of G. L. c. 40A, § 5, if the Second Protest Petition was not successful, but less than the three-fourths vote that would be required if the Second Protest Petition had been successful in meeting the twenty percent threshold.

17. On June 26, 2017, Newton Mayor Setti Warren signed the zoning amendment, rezoning the Rezoned Area, as proposed with the Second Application, to MU4.

DISCUSSION

"Summary judgment is granted where there are no issues of genuine material fact, and the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Ng Bros. Constr. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 643-644 (2002); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56 (c). "The moving party bears the burden of affirmatively showing that there is no triable issue of fact." Ng Bros. Constr., supra, 436 Mass. at 644. In determining whether genuine issues of fact exist, the court must draw all inferences from the underlying facts in the light most favorable to the party opposing the motion. See Attorney Gen. v. Bailey, 386 Mass. 367 , 371, cert. denied, 459 U.S. 970 (1982). Whether a fact is material or not is determined by the substantive law, and "an adverse party may not manufacture disputes by conclusory factual assertions." See Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986); Ng Bros. Constr., supra, 436 Mass. at 648. When appropriate, summary judgment may be entered against the moving party and may be limited to certain issues. Community Nat'l Bank v. Dawes, 369 Mass. 550 , 553 (1976); Mass. R. Civ. P. 56 (c).

INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTEST PROVISION IN GENERAL LAWS c. 40A, § 5

A determination whether the plaintiffs met the threshold for a successful protest requires a calculation of the quotient, where the numerator is the "area of the land" owned by protesting owners whose land is "immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet" from the land to be rezoned, and where the denominator is the "area of the land immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet" from the land to be rezoned. If the quotient derived from this calculation is at least twenty percent, the protest is successful and a three-fourths vote will be required to adopt the zoning change. See G. L. c. 40A, § 5, fifth para.

While the calculation is straightforward, determination of the components of the calculation - the numerator, consisting of the area of land owned by those whose land is immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet from the rezoned land; and the denominator, consisting of the area of land extending three hundred feet from the rezoned land - is less so. The plaintiffs, [Note 10] the City Council, and the Developer all offer differing interpretations of the various components of the protest provision, agreeing on some points and diverging on others. They differ on the contents of the numerator: the City Council argues that the protesters' land cannot be included unless it abuts the land to be rezoned; the plaintiffs and even the Developer rely on a more forgiving interpretation, which would allow a protest by any owner whose land lies within three hundred feet of the land to be rezoned, regardless of whether it abuts the land to be rezoned.

Similarly, the parties differ on the contents of the denominator: the Developer argues that the denominator includes all land "immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet" from the land to be rezoned; the plaintiffs variously argue that land in streets, land owned by the Commonwealth (including portions of the Massachusetts Turnpike and the Walnut Street Bridge) and land owned or under agreement by the Developer, in particular the "B2 Area" which is part of the proposed development but not part of the land proposed to be rezoned, should be excluded from the total area of land in the denominator of the calculation.

These are consequential differences, as the plaintiffs will be foreclosed from taking advantage of the protest provision if their land is required to be, but is not, "immediately adjacent" to the land to be rezoned; and they similarly will fail in their protest if the area of land they own is divided by the total of all land within three hundred feet of the land to be rezoned, with no exclusions for land owned by the Developer and land in streets and highways, as they concede they do not meet the twenty percent threshold under such circumstances. To resolve these disagreements, it is appropriate to look not only to the language of the statute, but to the extent the statute is ambiguous, to its legislative history as well.

"When a statute is 'capable of being understood by reasonably well-informed persons in two or more different senses,' it is ambiguous." Meyer v. Nantucket, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 385 , 390 (2010), quoting Falmouth v. Civil Serv. Comm'n, 447 Mass. 814 , 818 (2006). Using principles of statutory construction to interpret its meaning, the court looks "to the intent of the Legislature 'ascertained from all its words construed by the ordinary and approved usage of the language, considered in connection with the cause of its enactment, the mischief or imperfection to be remedied and the main object to be accomplished, to the end that the purpose of its framers may be effectuated."' DiFiore v. American Airlines, Inc., 454 Mass. 486 , 490 (2009), quoting Industrial Fin. Corp. v. State Tax Comm'n, 367 Mass. 360 , 364 (1975). The court is also guided by the caution that must be exercised in interpreting a provision that requires an even greater supermajority vote than is ordinarily required in voting on a zoning amendment. A successful protest petition under G. L. c. 40A, § 5, "derogates from the normal legislative process by majority rule even more drastically than the statutory two-thirds rule . . . which otherwise applies to the enacting of zoning amendment. The limitations upon and conditions of that leverage must therefore be strictly enforced." Parisi v. Gloucester, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 682 ,683 (1975).

Legislative History

In 1923, the United States Department of Commerce issued the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (the "SSZEA"), meant to serve as a model zoning enabling act. U.S. Dep't of Commerce, A Standard State Zoning Enabling Act § 5 (rev. ed. 1926). The SSZEA included a provision for a landowners' protest against zoning changes, which appears in many states' zoning acts. Id. The SSZEA's protest language provided in relevant part:

"In case, however, of a protest against such change, signed by the owners of 20 per cent or more either of the area of the lots included in such proposed change, or of those immediately adjacent in the rear thereof extending__ feet therefrom, or of those directly opposite thereto extending__ feet from the street frontage of such opposite lots, such amendment shall not become effective except by the favorable vote of three-fourths of all the members of the legislative body of such municipality."

SSZEA at 7-8.

The protest provision first appeared in Massachusetts in G. L. c. 40, § 27, when the Legislature enacted "An Act Revising the Municipal Zoning Laws," and adopted some of the language found in the SSZEA. See St. 1933 c. 269, § 1. Section 27 provided in relevant part:

"No change of any such ordinance or by-law shall be adopted except by a two thirds vote of all the members of the city council . . . provided, that in case there is filed . . . a written protest against such change, stating the reasons, duly signed by the owners of twenty per cent or more of the area of the land proposed to be included in such change, or of the area of the land immediately adjacent, extending three hundred feet therefrom, or of the area of other land within two hundred feet of the land proposed to be included in such change, no such change of any such ordinance shall be adopted except by a unanimous vote of all the members of the city council . . . if it consists of less than nine members or, if it consists of nine or more members, by a three fourths vote . . . ."

Id. [Note 11] The plain meaning of the language in Section 27 is that three categories of landowners have a right to file a protest against a zoning amendment: 1) owners of the area of the land that will be included in the zoning change; 2) owners of the area of the land immediately adjacent to the proposed zoning change and extending three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned; and 3) owners of other land that is within two hundred feet of the land to be rezoned, but which need not be immediately adjacent to the land to be rezoned.

In December, 1971, the Massachusetts Department of Community Affairs (the "DCA") published "1972 Report on Zoning in Massachusetts: Proposed Changes and Additions to Zoning Enabling Act Chapter 40A" (the "DCA Report"), in which the DCA made recommendations for a comprehensive revision of Chapter 40A. [Note 12] The DCA determined that the "veto power given to a minority of the voters by the extraordinary majority requirements of [the protest provision] makes it unnecessarily difficult to enact progressive changes in existing by-laws." DCA Report, at 34. Claiming that as a result of this difficult hurdle to zoning changes, boards of appeals engaged in "ad hoc rezoning through improper use of the variance granting power," the DCA recommended that the protest provision be abandoned. Id.

When the Legislature amended Chapter 40A in 1975 it retained the protest provision, moving it from Section 7 to Section 5. However, the protest provision was revised, to remove as eligible protesters, the category of owners of "other land within two hundred feet" from the land proposed to be rezoned. See St. 1975, c. 808, § 3. Considering the removal of that category of owners from those eligible to protest, in connection with the DCA's recommendations that the protest provision be abandoned altogether, it is apparent that the Legislature intended to narrow the class of landowners eligible to protest, thus addressing the perceived "mischief or imperfection"--difficulty in enacting progressive change--that resulted from previous versions of the protest provision. See DCA Report, at 34; DiFiore v. American Airlines, Inc., supra, 454 Mass. at 490-493 (examining legislative history of statutory amendment and language to determine Legislature's intent). In its present form, Section 5 allows a protest by only two of the three categories of owners previously qualified to protest: "owners of twenty per cent or more of the area of the land proposed to be included in such change or of the area of the land immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet therefrom . . . ." G. L. c. 40A, § 5.

"Immediately Adjacent"

"A statute should be construed so as to give effect to each word, and no word shall be regarded as surplusage." Recinos v. Escobar, 473 Mass. 734 , 742-743 (2016), quoting Ropes & Gray LLP v. Jalbert, 454 Mass. 407 , 412 (2009).

Chapter 40A does not define the term "immediately adjacent." Where a statute does not define a word or term, the court looks to its ordinary meaning. See Kain v. Department of Envtl. Prot., 474 Mass. 278 , 291 (2016). The American Heritage College Dictionary defines "adjacent" as: "adj. 1. Close to; lying near: adjacent cities. 2. Next to; adjoining: adjacent garden plots." The American Heritage College Dictionary 17 (4th ed. 2002). As Black's Law Dictionary states in its definition of "adjacent," this means "not necessarily touching." Black's Law Dictionary 42 (7th ed. 1999). The word "immediately" is defined as "with no intermediary; directly" in the American Heritage College Dictionary, which defines "intermediary" as "[e]xisting or occurring between"; Black's Law Dictionary defines "immediate" as "[n]ot separated by other persons or things< her immediate neighbor>." See American Heritage College Dictionary at 692, 724; Black's Law Dictionary at 751. Because land that is adjacent to a parcel of land can either mean land that touches the parcel or land that is simply near the parcel, the Legislature's use of the word "immediately" to modify "adjacent" indicates that the Legislature intended to establish that the land must touch the parcel ofland to be rezoned. Concluding otherwise would render the word "immediately" as surplusage. See Recinos v. Escobar, supra, 473 Mass. at 742-743.

Giving effect to both "immediately" and "adjacent" produces the result that for land to be immediately adjacent to the land to be rezoned, it must touch, or abut, the rezoned land. [Note 13] See Stop & Shop Supermkt. Co. v. Urstadt Biddle Properties, Inc., 433 Mass. 285 (2001) ("The statute is to be construed as written, in keeping with its plain meaning, so as to give some effect to each word"). This is further evidenced by the Legislature's removal of "other land within two hundred feet of the land proposed to be included in such change" when it enacted the current version of the protest provision. See St. 1975, c. 808, § 3, inserting G. L. c. 40A, § 5. [Note 14] "Where the Legislature has deleted such language, apparently purposefully, the current version of the statute cannot be interpreted to include the rejected requirement." Abrahamson v. Estate of LeBold, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 233 , 227, rev. denied, 475 Mass. 1102 (2016). The deleted clause, "other land within two hundred feet of the land proposed to be included in such change" included a category of owners of land who could protest a proposed zoning amendment: those whose land was within two hundred feet of the land proposed to be rezoned, but whose land was not "immediately adjacent" thereto. Construing the statute to mean that all landowners within three hundred feet of the area to be rezoned are eligible to protest leads to the result that a person owning land some distance away from but not abutting the land to be rezoned, as long as it is within three hundred feet, would be qualified to protest, thus rendering the phrase "immediately adjacent" superfluous. Such an interpretation would, in effect, add back to the statute the language deleted by the 1975 revision of the protest provision removing the phrase that allowed a protest to be effectuated by owners of "other land within two hundred feet," without a requirement that the land be "immediately adjacent" to the land to be rezoned. It would be inappropriate to accept an interpretation of the statute that, in effect, would reinsert a phrase that the Legislature has chosen to delete. See Duracraft Corp. v. Holmes Products Corp., 427 Mass. 156 , 164 (1998).

At the hearing on the parties' cross-motions, counsel for Slattery, citing Dennis Housing Corp. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Dennis, 439 Mass. 71 (2003), argued that interpreting the term "immediately adjacent" in its literal sense would defeat the purpose of G. L. c. 40A, § 5. However, Slattery has not offered any support for the argument that the Legislature's intent in amending the statute was other than to narrow the class of landowners who could participate in a Section 5 protest to those whose land was included in the proposed rezoning and those whose land was immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet from the land proposed to be rezoned. Since the Legislature's intent, as evidenced by the legislative history, is apparent from a literal reading of the words in the statute, and this reading is confirmed by the legislative history, this is not an appropriate occasion for interpreting the statute in a "liberal, even if not literally exact, interpretation of certain words (in order) to accomplish the purpose indicated by the words as a whole . . . ." Dennis Housing Corp. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Dennis, 439 Mass. at 83. Contrast Intriligator v. Boston, 395 Mass. 489 , 491 (1985) ("literal approach" to statutory construction not appropriate in interpreting effect of adoption of Massachusetts Tort Claims Act, G. L. c. 258, on municipal liability for injuries caused by accumulations of snow and ice on park roads, where legislative intent to preserve immunity in certain circumstances is obvious). "'The object of all statutory construction is to ascertain the true intent of the Legislature from the words used."' Dennis Housing Corp. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Dennis, supra, 439 Mass. at 83, quoting Champigny v. Commonwealth, 422 Mass. 249 , 251 (1996). Here, the term "immediately adjacent" is not defined in either G. L. c. 40A, § 5, or elsewhere in G. L. c. 40A; therefore, the words must be given their ordinary meaning. Taking the ordinary meaning of the words "immediately" and "adjacent", as confirmed by the legislative history, the court interprets "area of land immediately adjacent" to mean land that directly abuts the Rezoned Area. As the Parisi court explained in rejecting a similarly strained interpretation of a different aspect of the protest provision of G. L. c. 40A, § 5, this court is "not inclined to strain the grammatical structure" of the provision to reach the contrary result urged by the plaintiffs. Parisi v. Gloucester, supra, 3 Mass. App. Ct. at 682.

"Extending Three Hundred Feet Therefrom"

The protest provision provides that signatures of the owners of twenty percent or more of "the area of the land immediately adjacent" to the land to be rezoned and "extending three hundred feet therefrom" are necessary to file a successful protest. G. L. c. 40A, § 5. The City Council, the Developer, and the plaintiffs agree that the phrase "extending three hundred feet therefrom" serves to place a limit on the depth of a landowner's directly abutting land that may be counted, so that if the landowner's directly abutting land extends beyond three hundred feet, only the area of land within the first three hundred feet is eligible to be counted toward the protest. Beyond that, the parties' interpretations differ as to which land should be included in the denominator of the equation in determining whether the protesting plaintiffs own twenty percent of the land extending three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned. The City Council's interpretation is that only land directly abutting and extending three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned is included, and that the streets are excluded and serve to cut off any adjacency of land opposite the streets; thus the City Council's position is that the denominator is "zero." The Developer argues that all land extending for a radius of three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned must be included without exception. The plaintiffs argue for various exclusions. They argue that land in the streets within the three hundred foot radius of the land to be rezoned should be excluded from the denominator. The plaintiffs also argue more expansively that the B2 Area (which is part of the land owned by the Developer but which is not proposed to be rezoned), land owned by landowners who have entered into agreements with the Developer, and highways and bridges and other land owned by the Commonwealth should not be considered as land "extending three hundred feet" from the land to be rezoned, and must be excluded from the denominator.

For the reasons stated below, the court concludes that there is no basis for excluding from "the area of the land extending three hundred feet" from the land to be rezoned, land in streets or the Massachusetts Turnpike, other land owned by the Commonwealth, land owned or under agreement by the Developer, the B2 Area, or other land sought by the plaintiffs to be excluded from the denominator.

The plaintiffs argue that the B2 Area should be excluded because it is owned by the Developer, and that the land of landowners entering into an agreement with the Developer should be excluded from the denominator; the court disagrees. There is nothing in the language of G. L. c. 40A, § 5, that excludes other land, owned by the proponent of a rezoning petition but that will not be rezoned, from being counted in the calculation of the area of land extending three hundred feet from the land proposed to be rezoned. The statute calls for all land extending three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned to be included in the denominator, not all land except for land owned by a developer. Nor does the statute allow the court to examine the Developer's intent in excluding the B2 Area from the area proposed to be rezoned, as the plaintiffs urge, and to penalize the Developer if the Developer's intent was to create a buffer zone that prevented the plaintiffs from claiming that their land was "immediately adjacent" to the land to be rezoned. Accordingly, the court concludes that the statute does not permit the exclusion of the B2 Area from being counted as part of the land extending three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned.

The court also disagrees with the plaintiffs' assertion that the area of land in the streets, the Massachusetts Turnpike and other publicly owned land should be excluded. Again, G. L. c. 40A, § 5 provides, "twenty per cent or more of the area of the land proposed to be included in such change or of the area of the land immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet therefrom . . . ." (emphasis added). It does not call for inclusion of all land extending three hundred feet except for land in streets or land owned by public entities, or owned by any particular owner or class of owner. By calling for a measurement on the basis of "land" instead of "lots," the Legislature eliminated the idea of discriminating between parcels of land on the basis of ownership. While the plaintiffs argue that only owners of "lots" should be eligible to protest, the statute does not specify "lots," despite the fact that the SSZEA's model statute used the term "lots." See SSZEA at 7-8. The Legislature used the word "land" in its version of the protest provision, and streets are land. The use of the term "land" instead of the term "lots" indicates an intent by the Legislature to include in the denominator all land extending three hundred feet from the land proposed to be rezoned, regardless of ownership or character of the land.

In support of their argument that streets should be excluded from the denominator, the plaintiffs point to the notice requirements in G. L. c. 40A, § 11, which provide that notices of public hearings are to be sent to "parties in interest," and that such "parties in interest" "as used in this chapter shall mean the petitioner, abutters, owners of land directly opposite on any public or private street or way, and abutters to abutters within three hundred feet of the property line of the petitioner . . . ." This is offered as evidence of an intent to exclude land in streets when considering matters of notice to nearby landowners. Section 11, however, discusses the requirements for notice of special permits and variances. G. L. c. 40A, § 11. Section 5 contains its own requirements as to who may participate in a protest and likewise contains its own provision for those entitled to receive notice of a public hearing on a proposed zoning change; the phrase "parties in interest" does not appear in Section 5. The only sections in Chapter 40A in which the phrase "parties in interest" appears are §§ 9, 9A, 10, 11, 15, and 16, all of which pertain to the permit granting authority, special permits, variances, appeals to the permit granting authority, and permits. The "parties in interest" treatment of owners across a street, treating them as abutters for the purpose of notice of certain public hearings, is glaringly not made applicable to Section 5 when looking at Chapter 40A as a whole. The statute's separate treatment of owners across a street as abutters for the purpose of notice of hearings for other purposes is evidence that landowners across a street are not intended to be treated as abutters for the purposes of the protest provision, and that the land in the street is therefore not intended to be excluded from the denominator of all land to be included when calculating the percentage of ownership of the protesting landowners. Section 5 does not classify the area of land within three hundred feet of the land proposed to be rezoned into different categories of real property, as does Section 11 with respect to determination of parties in interest. If the Legislature intended to treat the protest provision relating to zoning amendments the same as the notice provision for variance or special permit hearings, it could have simply allowed the protest provision to be submitted by some percentage of Section 11 "parties in interest," instead of providing an entirely different measure of who was entitled to submit a protest in Section 5. [Note 15]

PLAINTIFFS FAIL TO MEET THE TWENTY PERCENT THRESHOLD UNDER A MORE INCLUSIVE INTERPRETATION

Even if the court were to apply the alternate, more expansive interpretation urged by the plaintiffs, that the owners of all land within three hundred feet of the land to be rezoned are eligible to protest, regardless whether their land is immediately adjacent to the land to be rezoned, the plaintiffs still fail to trigger the three-fourths vote of City Council.

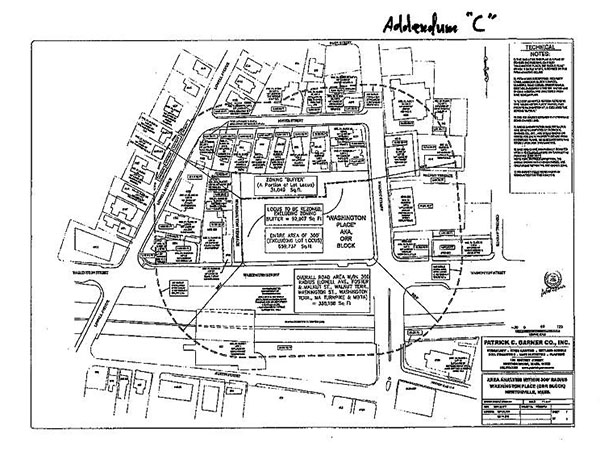

The plaintiffs and the Developer have submitted plans in support of their motions depicting a three hundred foot radius drawn around the Rezoned Area. While the parties disagree over which plan the court should use to determine whether the protest was sufficient, it is immaterial, as under either plan the plaintiffs do not reach the requisite twenty percent.

The Developer's Plan

The Developer's plan was prepared by Joshua G. Swerling, a professional engineer, utilizing the City's GIS data to calculate the area of land within three hundred feet of the Rezoned Area (the "Swerling Plan"). [Note 16] The Swerling Plan measured the total area of land within three hundred feet of the area to be rezoned as comprising 687,393 square feet, which includes, in addition to privately owned land, the area of the streets, the Massachusetts Turnpike, the Walnut Street Bridge, and other land owned by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation ("MassDOT"). Measuring the area of land owned by signatories to the Second Protest Petition that falls within the three hundred foot radius provides a total of 79,233 square feet of protest land. The result is that the protesting landowners own 11.5% of the area of land within three hundred feet of the Rezoned Area, short of the requisite twenty percent for a successful protest. It is undisputed that in arriving at 11.5% of protesting land area, the Developer only included the area of land appearing on the Swerling Plan that is owned by the landowners who signed the Second Protest Petition and Slattery, who later joined the protest.

The Plaintiffs' Plan

The plaintiffs take issue with the Swerling Plan for a number of reasons. [Note 17] They contend that: 1) the area of the streets and the Massachusetts Turnpike should be excluded from the calculation; 2) the B2 Area should be excluded because it is owned by the Developer; 3) land owned by those entering into agreements with the Developer should be excluded; and 4) landowners who signed the First Protest Petition should be included in the calculation.

The plaintiffs rely on a plan developed by Patrick C. Garner, a professional land surveyor (the "Garner Plan"). [Note 18] Mr. Garner explained in an affidavit that he created a base map utilizing the Swerling Plan, adopting the property and street boundary lines, and the three hundred foot radius extending from the Rezoned Area. Mr. Garner then reviewed recorded deeds and plans for each parcel of land falling within the three hundred foot radius to determine the lot areas. Including the streets, but excluding the B2 Area, the Garner Plan produces a land area of 659,737 square feet. The plaintiffs total the area of land owned by protesters as 103,121 square feet, which produces 15.6%, short of the required twenty percent even when including in the numerator the land of owners who signed the First, but not the Second Protest Petition. Consequently, the plaintiffs' interpretation, to produce a successful result of twenty percent or greater, relies not only on inclusion of the land of an owner who signed the First Protest Petition, but not the Second Protest Petition, thus making the numerator larger; but also relies on exclusion from the denominator of the B2 Area (which has been referred to as a "buffer zone"), as well as land in streets and other land, in order to make the denominator smaller.

As an initial matter, even if the court were to apply an interpretation that includes the owners of all land within three hundred feet of the Rezoned Area as eligible to sign a protest, only the area of land of landowners who signed the Second Protest Petition would be included. The Developer withdrew its initial request for rezoning and submitted a second rezoning request, with an altered area of land to be rezoned. The plaintiffs cannot combine the First Protest Petition with the Second Protest Petition, as the statute calls for the protest to be signed by landowners who are protesting "such change," not a previous, withdrawn proposed change in zoning. Further, the plaintiffs included in their calculation land owned by an owner who signed the First Protest Petition, but subsequently rescinded that signature in a letter to the City Council. [Note 19] As such, that area of land cannot be included either; deducting the aforementioned areas of land results in 79,233 square feet of protesting land.

Just as it is not appropriate to include in the numerator the land of owners who did not sign the Second Protest Petition, neither is it appropriate, for reasons discussed above, to exclude from the denominator land in streets or highways, land owned by the Commonwealth, the B2 Area, other land owned by or under agreement to the Developer, or any other land extending three hundred feet from the Rezoned Area. After including in the denominator the streets and the B2 Area that will not be rezoned, and excluding from the numerator signatories of the First Protest Petition as well as the owners of 15 Foster Street who withdrew their protest, the plaintiffs, utilizing the Garner Plan, only reach an area of protesting land equaling 11.5%. As the Garner Plan's total area of land extending three hundred feet from the Rezoned Area excluded the B2 Area's 31,049 square feet, the B2 Area must be added to the 659,737 square feet, producing a total area of land extending three hundred feet from the Rezoned Area of 690,786 square feet. Therefore, using the plaintiffs' Garner Plan, but excluding from the numerator the land of owners who signed the First Protest Petition, and including all land extending three hundred feet from the Rezoned Area in the denominator, the calculation required by the protest provision results as follows: 79,233 square feet of land owned by landowners whose land is within three hundred feet of the land to be rezoned ÷ 690,786 square feet of land extending three hundred feet from the land to be rezoned = 11.5%. As is noted above, even if those who signed the First Protest Petition are included, the percentage reaches only 15.6%; also as discussed above, the court has concluded that none of the plaintiffs own land that is immediately adjacent to the land to be rezoned within the meaning of the statute.

The plaintiffs' protest, under either an interpretation of the statute requiring that the land of the protesting owners be "immediately adjacent" to the land to be rezoned, or an interpretation allowing a protest by owners of any land within three hundred feet, regardless of whether the land is immediately adjacent to the land to be rezoned, was not sufficient to trigger a requirement of a three-fourths vote of the City Council. While the plaintiffs contend that a literal construction of the protest provision produces an inequitable result, it is not for the court to bend the statute to produce a result the plaintiffs think is fair to their position. "When statutory language yields a plain meaning, arguments that its application in a particular case will cause a hardship or lead to an inequity should be addressed to the Legislature." New England Survey Systems, Inc. v. Department of Indus. Accidents, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 631 ,634 (2016), quoting Larkin v. Charlestown Sav. Bank, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 178 , 183-184 (1979). See DiFiore v. American Airlines, Inc., supra, 454 Mass. at 490-491 ("[O]ur respect for the Legislature's considered judgment dictates that we interpret the statute to be sensible, rejecting unreasonable interpretations unless the clear meaning of the language requires such an interpretation").

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the defendants' motion for partial summary judgment is ALLOWED, and the plaintiffs' cross-motions for partial summary judgment are DENIED.

Judgment will enter dismissing those counts of the plaintiffs' complaints contesting the adoption of the zoning change on the basis of the protest provision of G. L. c. 40A, § 5, fifth para., when final judgment is entered in the remainder of the present consolidated actions.

"No zoning ordinance or by-law or amendment thereto shall be adopted or changed except by a two-thirds vote of all the members of the town council, or of the city council where there is a commission form of government or a single branch, or of each branch where there are two branches, or by a two-thirds vote of a town meeting; provided, however, that if in a city or town with a council of fewer than twenty-five members there is filed with the clerk prior to fmal action by the council a written protest against such change, stating the reasons duly signed by owners of twenty per cent or more of the area of the land proposed to be included in such change or of the area of the land immediately adjacent extending three hundred feet therefrom, no such change of any such ordinance shall be adopted except by a three-fourths vote of all members."

MAURA J. HARRINGTON v. NEWTON CITY COUNCIL, CITY OF NEWTON SPECIAL PERMIT GRANTING AUTHORITY, AND MARK NEWTONVILLE, LLC.

MAURA J. HARRINGTON v. NEWTON CITY COUNCIL, CITY OF NEWTON SPECIAL PERMIT GRANTING AUTHORITY, AND MARK NEWTONVILLE, LLC.