The developer of a proposed affordable housing development with thirty-two dwelling units, seeking to demonstrate to the Hingham Zoning Board of Appeals that it has sufficient access to the proposed development, added to its proposed plan an additional access road from Autumn Circle, a public way, to the proposed development. The problem, and thus the issue in this case, is that the proposed roadway leading to the development from Autumn Circle must utilize a right of way on the land of the two plaintiffs, and they argue that the developer has no rights to cross their land to access the proposed development from Autumn Circle. For reasons stated below, this court agrees with the plaintiffs, and will enter a judgment declaring that the developer does not have the right to pass over the land of the plaintiffs to access the proposed development.

The plaintiffs commenced this action on February 13, 2018, and filed a "First Amended Verified Complaint" on April 25, 2018. The complaint, as amended, asserts "try title" claims pursuant to G. L. c. 240, §§ 1-5, seeking to force the developer to try its title to the disputed right of way (Counts I and II); a declaratory judgment count seeking a declaration that the developer does not have any rights over the plaintiffs' properties (Count III); claims of extinguishment of the disputed right of way by adverse possession (Counts IV and V); and a claim for preliminary injunctive relief (Count VI). The defendants filed an answer to the amended complaint on May 18, 2018. Their answer included a counterclaim seeking declaratory relief with respect to their rights in the disputed way.

The plaintiffs also filed a motion for a preliminary injunction. A hearing was held on the request for preliminary injunctive relief on May 14, 2018, and on May 16, 2018 the court issued an Order allowing the plaintiffs' motion in part, enjoining the defendants from entering onto the plaintiffs' properties, including the claimed right of way. The present "partial" motion for judgment on the pleadings was filed by the plaintiffs on June 15, 2018, seeking judgment on Count III only, for a declaratory judgment that the right of way over the plaintiffs' properties claimed by the defendants is not an enforceable right of way or easement. Although seeking judgment on only one count, and thus termed a "partial" motion for judgment on the pleadings, the plaintiffs and the defendants agree that if the plaintiffs are successful on Count III, the other counts of the First Amended Verified Complaint would be moot. The defendants filed their opposition on July 13, 2018, and the court took the motion under advisement following oral arguments on August 14, 2018.

FACTS

For the purposes of this Rule 12(c) motion for judgment on the pleadings, the facts pleaded by the parties are accepted as true. The documents attached by the plaintiffs to their First Amended Verified Complaint and by the defendants to their answer are part of the pleadings and will be accepted as documents to be considered in deciding the Rule 12(c) motion. See, Mass. R. Civ. P. 10(c) ("A copy of any written instrument which is an exhibit to a pleading is a part thereof for all purposes"). See also, Schaer v. Brandeis University, 432 Mass. 474 , 477 (2000) (in considering motion to dismiss, "items appearing in the record of the case, and exhibits attached to the complaint, also may be taken into account"). See also Jarosz v. Palmer, 436 Mass. 526 , 530 (2002).

The facts pleaded in the First Amended Verified Complaint, the Answer, and shown by the exhibits to the First Amended Verified Complaint and to the Answer, are as follows: [Note 1]

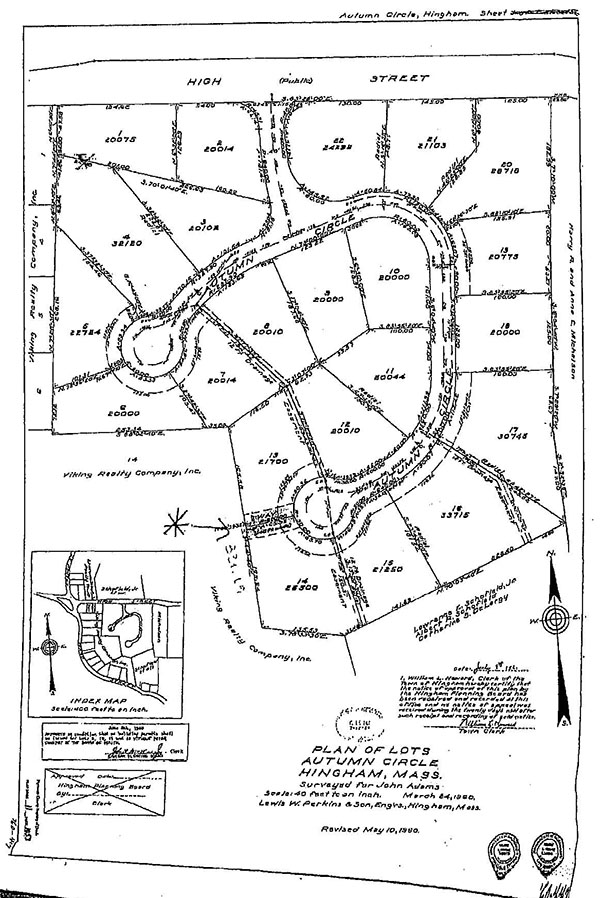

1. The Autumn Circle Subdivision Plan (the "Subdivision Plan") was recorded with the Plymouth County Registry of Deeds ("Registry") in Plan Book 11, Page 1053, as Plan No. 447 of 1960, on July 15, 1960. [Note 2]

2. The land comprising the Autumn Circle Subdivision had been conveyed, prior to the recording of the Subdivision Plan, to Hingham Estates, Inc. on June 21, 1960, by a deed recorded with the Registry in Book 2783, Page 73.

3. Abutting the land comprising the Autumn Circle Subdivision at the time of the June 21, 1960 conveyance and at the time of the recording of the Subdivision Plan on July 15, 1960, was land then owned by Viking Realty Company, Inc., ("Viking Realty") a predecessor in interest of the current defendant Viking Lane, LLC, which is the present record owner of the abutting land (the "Viking Land"). The Viking Land, then as now, is bounded roughly by the Autumn Circle Subdivision to the north and east, and by land of others (resulting from Viking Realty's sale of some lots formerly part of the Viking Land) and Ward Street, a public way in Hingham, to the south and west.

4. Defendant River Stone LLC ("River Stone") has rights to purchase the Viking Land from Viking Lane, LLC pursuant to a purchase and sale agreement. River Stone is the present applicant for the G. L. c. 40B development proposed for the Viking Land.

5. The Viking Land and the land comprising the Autumn Circle Subdivision did not share a common grantor at the time the subdivision land was conveyed to Hingham Estates, Inc., at the time the Subdivision Plan was approved and recorded, or at any other time since.

6. The Subdivision Plan depicts a "Way 40 feet wide," (hereinafter, the "Way") straddling the common boundary between Lots 13 and 14 in the Subdivision, with twenty feet of its width on each of the two lots, running the length of the boundary line from one of the two cul-de-sacs of Autumn Circle to the western boundary of the two lots, where the subdivision property is abutted by the Viking Land.

7. The Way was apparently, although not conclusively, included on the Subdivision Plan as a result of a requirement in the Hingham Planning Board's Rules and Regulations that in any subdivision plan, "[p]rovision shall be made for the proper projection of ways, if adjoining property is not subdivided." For the purposes of the present motion, the court assumes, as argued by the defendants, that the quoted regulation is the reason the Way was placed on the Subdivision Plan.

8. The first deed out of Lot 14 by the developer of the Autumn Circle Subdivision, recorded with the Registry on June 22, 1961, in Book 2871, Page 435, included the following language: "Together with and subject to a right of way over a strip of land 40 feet wide as shown on [the Subdivision Plan] extending from Autumn Circle to land of Viking Realty Company, Inc. as shown on said plan, one half of said strip being part of Lot #13 on said plan and the other half being part of said Lot #14 hereinbefore mentioned." This is the only explicit mention of the Way in any deed conveying an interest in Lot 14.

9. There is no mention of the Way in any deed conveying an interest in Lot 13.

10. Notwithstanding the reference to the Way in the first deed out of Lot 14, there has never been an explicit grant or other conveyance by any owner of the land shown on the Subdivision Plan of any rights in the Way. In particular, there is no deed or other grant of an easement or other interest in the Way in the chain of title of the land owned by Viking Realty or any of its successors in interest.

11. The plaintiffs Anne C. Mullen and Joyce A. Bethoney, own, respectively, Lots 14 and 13 in the Autumn Circle Subdivision.

12. The Way has never been built on the ground or used by Viking Realty or any of its successors in interest.

13. At the time the Subdivision Plan was approved and recorded in 1960, the Viking Land included several hundred feet of frontage on Ward Street, some of which Viking Realty sold off as "approval under the subdivision control law not required" ("ANR") lots in 1964 and 1965. After the sale of ANR lots, Viking Realty retained access to Ward Street over a 40-foot wide way to be known as Viking Lane, and an additional stretch of frontage along Ward Street of approximately 200 feet further to the east along Ward Street. That frontage remains part of the Viking Land today.

14. On April 21, 1964, the town of Hingham, by a taking recorded in the Registry in Book 3107, Page 400, took the layout of Autumn Circle for public highway purposes, and took a drainage easement only, in the Way.

15. In 2016, River Stone submitted an application to the Hingham Zoning Board of Appeals for approval of a 36-unit affordable housing development pursuant to G. L. c. 40B, §§ 21-23, to be constructed on the Viking Land. The proposal called for access to the development to be entirely from the frontage on Ward Street.

16. In January, 2018, River Stone submitted a revised application, reducing the number of units from thirty-six to thirty-two, and proposing, for the first time, access to and from the proposed development over the Way, to Autumn Circle. This access would be in addition to access from the frontage on Ward Street in the location of the original proposed Viking Lane. The revised proposal does not propose to use any of the defendants' additional frontage along Ward Street for a second or third access.

DISCUSSION

The parties agree that the facts in this case are not in dispute; the documents submitted to the court in conjunction with or outside the pleadings are largely matters of record, specifically, conveyancing documents, recorded plans and the Rules and Regulations of the Hingham Planning Board as in effect in 1960 when the Subdivision Plan was approved and recorded. Accordingly, the present motion for judgment on the pleadings is treated as a motion for summary judgment. See Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(c).

The plaintiffs posit that the undisputed facts in the record require a finding that the owner of the Viking Land does not have any rights over the Way, and that they are entitled to a judgment that would preclude the use of the Way for access to or from the affordable housing development proposed on the Viking Land. The defendants seek a determination that they have rights over the Way, or, at a minimum, a ruling that there are material facts in dispute and that they are entitled to prove the existence of rights in the Way. The defendants argue first that they have the benefit of a direct grant of rights in the Way by virtue of its appearance on the Subdivision Plan. Failing that, the defendants argue that they are entitled to a determination that the Viking Land has the benefit of access over the Way by estoppel, by implication, or by eminent domain as a result of the town of Hingham's taking of certain rights in Autumn Circle. The court's discussion, below, addresses each of these arguments, and does not differ in its conclusions, as the offered facts do not differ, from the court's discussion of these issues in its ruling on the plaintiffs' earlier motion for preliminary injunctive relief.

Easement by Direct Grant or Reservation

The defendants first argue that they have the benefit of a granted easement over the Way by virtue of the Hingham Planning Board's requirement that the Way be shown on the Autumn Circle Subdivision Plan, the inclusion of the Way on the Subdivision Plan, and the recording of the Subdivision Plan. While the inclusion of a way or easement on a subdivision plan, in combination with a grant or reservation of the way or easement in a deed or other conveyancing document, could well establish a right to use a way shown on a plan, there is no case holding that the mere depiction of a way on an approved subdivision plan, or a condition of approval on a subdivision plan, without more, can operate as a grant of an easement or restriction. "Subdivision approvals are not permanently etched in stone, but can be modified in accordance with the provisions of G. L. c. 41, § 81W." Samuelson v. Planning Bd. of Orleans, 86 Mass. App. Ct. 901 , 902 (2014). There is a distinction "between land use restrictions 'created by deed, other instrument, or a will,' and land use restrictions imposed as a condition to the discretionary grant of regulatory approval under the police power." Id., quoting Killorin v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 655 , 658 (2011). As there were never any rights granted or reserved with respect to the Way as shown on the Subdivision Plan, it had no more permanence than any other condition on any other subdivision plan that could be changed by a planning board pursuant to G. L. c. 41, § 81W.

Further, the mere depiction of a roadway on a subdivision plan does not serve to convey any property rights. The owner of abutting land gains no rights in the approved subdivision ways by virtue of their inclusion on a subdivision plan. Where the owner of land adjacent to a subdivision does not have an granted easement to use the roadways in the subdivision for access to the subdivision from adjacent land, even acquisition of ownership of a lot in the subdivision by the abutting landowner will not justify the use of the subdivision roadways for access to the adjacent land. Matthews v. Planning Bd. of Brewster, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 456 , 466 (2008). See also, Siok v. Planning Bd. of the Town of Ludlow, 23 LCR 597 (2015) (planning board could authorize deletion from approved plan of spur roadway intended to connect to adjacent undeveloped parcel where no easement over proposed roadway had been reserved or granted on original approval).

The undisputed facts in the present action are not different in any material respect from those presented to the court in Patel v. Planning Bd. of North Andover, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 477 (1989). In Patel, the North Andover Planning Board required the developer of a subdivision called Marbleridge Estates to show a future connection for a roadway on one of the subdivision lots, and to grant an easement for the future roadway so that when the adjacent land was developed, the roadways in the two subdivisions could be connected. The developer showed the intended future roadway on the plan, but the planning board neglected to obtain an easement over the lot with the proposed future roadway before certifying that the subdivision was complete and releasing the developer's performance bond. The lot on which the plan showed the future roadway was sold without any easement encumbering it, but with the roadway depicted clearly on the subdivision plan referred to in the grantee's deed. Years later, the planning board, in approving Abbott Village Estates, a subdivision of the adjacent land, required the Abbott Village Estates developer to build and incorporate into the new subdivision, the future roadway shown on the lot in the adjacent Marbleridge Estates subdivision. The owner of the lot on which the future roadway was to be located appealed the approval. The Appeals Court held that no easement authorizing the construction of the roadway was conveyed by virtue of its having been shown on a subdivision plan. "The mere approval and recording of a subdivision plan which refers to a roadway does not convey an easement in favor either of those owning property abutting the subdivision or the public generally." Id. at 480. Nor did it matter that the deed to the plaintiff, who was contesting the existence of the easement, referred to the subdivision plan showing the roadway, or that the plaintiff had actual knowledge that the proposed roadway easement was shown on the subdivision plan. Id. at 479-480. Under the principles articulated in Patel, there was no creation of an easement for the benefit of the Viking Land by express act of any owner of the Autumn Circle Subdivision land. As a matter of determining whether there was an express grant or reservation, the present facts are indistinguishable in any material way from the facts in Patel.

Easement by Estoppel

The defendants also argue that the undisputed facts may give rise to an easement by estoppel. An easement by estoppel generally may be created only when the dispute is between grantees or their successors in interest and their grantors or their successors in interest, which is not the case here. See Patel, supra, at 482 ("Neither of the two lines of estoppel cases has any application to the facts of the present case. Both categories of cases deal with the rights of grantees or their successors in title against their grantors and their successors in title"). See also Blue View Construction v. Town of Franklin, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 345 , 355 (2007) ("Thus, in each of those instances, easements by estoppel arise by virtue of the conveyance made by the grantor to the grantee"). As in Patel and Blue View, the defendants here seek to establish an easement by estoppel based on a conveyance that is outside their own chain of title. Contrary to the arguments of the defendants, Massachusetts courts have resisted efforts to recognize the creation of easements on broader principles of estoppel. Patel, supra, at 482; Blue View Construction, supra, at 355 ("Blue View relies on general estoppel principles in attempting to make its case. We have held, however, that such principles do not apply to the creation of easements").

The defendants argue in support of their estoppel theory that Viking Realty deeded out several ANR lots on Ward Street, thereby losing much of its frontage on Ward Street, in reliance on the existence of the Way as shown on the Subdivision Plan. This exact argument was rejected by the Appeals Court in Blue View Construction, and also ignores the fact that, unlike the developer who had deeded away all of its frontage in Blue View Construction, the present defendants still retain more than sufficient frontage on Ward Street to add additional access ways into their proposed development.

Easement by Implication

The defendants point to Perillo v. Knight, 86 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2014) (Rule 1:28 Memorandum and Order) as supporting a conclusion that, notwithstanding the lack of an express grant or reservation of easement, and notwithstanding the lack of a common grantor, an easement may be created by implication where the parties are shown to have intended the creation of an easement and the planning board's regulations did not require an express grant.

"[I]mplied easements, whether by grant or reservation, do not arise out of necessity alone. Their origin must be found in a presumed intent of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable." Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. 102 , 103 (1940). "The burden of proving the existence of an implied easement is on the party asserting it." Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006).

To the extent Perillo may be relied upon as precedent at all, the facts in Perillo are distinguishable from those in the present case. [Note 3] The plaintiff's predecessor in title in that case had explicitly negotiated an easement with one of the defendants, and the defendants demonstrated that they had relied on the completed negotiation by constructing a roadway on the new easement and by giving up another easement. The defendants, who would have the burden of proof to show the existence of a an easement by implication, have offered not even a suggestion in the record that the Way as shown on the Subdivision Plan resulted from anything other than the requirement of the planning board that the Way be shown on the plan to accommodate possible future development of the abutting land. Nor have the defendants offered any facts to show that Viking Realty or any of its successors in interest took any steps to implement any understanding of the existence of such an implied easement for more than fifty years after the approval of the subdivision.

The plaintiffs are entitled to rely on the absence of such facts where the defendants, with the burden of proof on this issue, have failed to demonstrate any facts that would support their argument that there was an agreement in place upon which to base a finding of an implied easement. "[A] party moving for summary judgment in a case in which the opposing party will have the burden of proof at trial is entitled to summary judgment if he demonstrates, by reference to material described in Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c), unmet by countervailing materials, that the party opposing the motion has no reasonable expectation of proving an essential element of that party's case. To be successful, a moving party need not submit affirmative evidence to negate one or more elements of the other party's claim

The motion must be supported by one or more of the materials listed in rule 56 (c) and, although that supporting material need not negate, that is, disprove, an essential element of the claim of the party on whom the burden of proof at trial will rest, it must demonstrate that proof of that element at trial is unlikely to be forthcoming." Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706 , 714 (1991).

With no facts offered by the defendants that would tend to support their theory of an implied easement, the case is within the ambit of the holding of Patel, and accordingly there is no basis for a finding that an easement by implication could be established or that there is any genuine issue of material fact on this issue.

Easement as a Result of the Roadway Taking

Finally, the defendants argue as well that they acquired easement rights as a result of the town of Hingham's taking of the roadway layout for Autumn Circle and the taking of a drainage easement in the Way. They acknowledge that the taking was of a drainage easement in the Way, not of an easement for passage, but they argue that because Viking Realty was included as a party to the taking, the taking of the drainage easement constituted a recognition of Viking Realty's rights in the Way. This argument is unavailing, as the town had no ability to grant what it did not own, and if the town mistakenly understood Viking to be the owner of an easement in the Way, that did not give the town the authority to grant such an easement. Simply put, "whatever the intent, one may not grant what one does not own . . . Thus, easements can be created only 'out of other land of the grantor, or reserved to the grantor out of the land granted; never out of the land of a stranger.'" Kitras v. Town of Aquinnah, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 285 , 292 (2005), quoting in part Richards v. Attleboro Branch R. Co., 153 Mass. 120 , 122 (1891). As in Kitras, in which the court held that the Commonwealth could not be found to have impliedly granted easements over land owned by others, the town of Hingham cannot in this case be found to have granted any easements over land owned by others where it did not explicitly take such easements by eminent domain.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons discussed above, the plaintiffs' "Partial Motion for Judgment on the Pleadings" is ALLOWED. Judgment will enter on Count III of the First Amended Complaint, and on the defendants' counterclaim, also seeking declaratory relief, declaring that neither Viking Realty Company, Inc. nor any of its successors in interest has any rights over the Way; and judgment will enter dismissing the remaining counts of the First Amended Verified Complaint as moot.

ANNE C. MULLEN and JOYCE A. BETHONEY v. VIKING LANE, LLC and RIVER STONE LLC

ANNE C. MULLEN and JOYCE A. BETHONEY v. VIKING LANE, LLC and RIVER STONE LLC