DAVID OWENS as trustee of the KMA REALTY TRUST vs. OYSTER POND HOMEOWNERS' ASSOCIATION TRUST

DAVID OWENS as trustee of the KMA REALTY TRUST vs. OYSTER POND HOMEOWNERS' ASSOCIATION TRUST

2019-15-000443-DECISION

October 22, 2019

Barnstable, ss.

LONG, J.

DECISION

Introduction

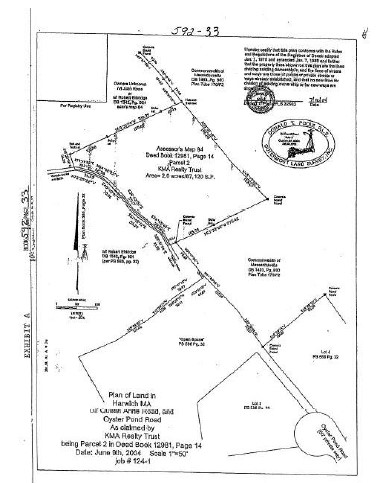

Plaintiff David Owens, in his capacity as trustee of the KMA Realty Trust, claims to own a two-acre woodland parcel in Harwich as located and depicted on a plan he prepared and recorded in 2004. A copy of that plan is attached as Ex. 1. The parcel is landlocked. However, Mr. Owens also claims to have an easement appurtenant to that parcel - express, implied, or prescriptive - along the route of an old cartpath whose traces go through the abutting land to the south and which he alleges would enable him to access and use a private subdivision way, Oyster Pond Road, that ultimately connects to the public Queen Anne Road. Whether such an easement exists and, if so, its location, dimensions, and scope of allowable use, are the ultimate issues in this lawsuit. But before those issues can be reached, there is a preliminary one. Does Mr. Owens own the parcel allegedly benefited? If the answer is "no", he has no standing to assert any easement rights on its behalf and this case must be dismissed.

Defendant Oyster Pond Homeowners' Association Trust - the homeowners' association for the Oyster Pond subdivision - owns both Oyster Pond Road and the subdivision open space through which the alleged easement runs. [Note 1] The Association thus has standing to challenge both the easement claim and Mr. Owens' title to the allegedly benefited land, see Hickey v. Pathways Association Inc., 472 Mass. 735 , 753 (2015), and has done so.

Rather than search for and join the other parties potentially affected by the easement claim at this time, Mr. Owens and the Association agreed to split the case into two parts and, as between themselves, [Note 2] litigate the ownership issue first, doing so in a case-stated trial with the court allowed to draw inferences from the evidence presented. If ownership is found, they agree that the easement issues should not be tried until all other potentially affected parties have been added to the case.

Mr. Owens stipulated that his claim to ownership is based solely on his claim of record title. He does not assert, and agrees he has no current basis for, a claim of adverse possession. [Note 3] Thus, the evidence was primarily documentary, with supplementation from the parties' joint statement of facts and the affidavits of their title examiners.

Based on that evidence, the credibility, reliability, and weight I found appropriate to its evaluation, [Note 4] and the reasonable inferences I drew from the evidence found credible and reliable, I find and rule as follows.

Facts and Discussion

As the party claiming title, Mr. Owens has the burden of proving that he owns the parcel at issue and must prove that he actually owns it, not just that he has a better claim than others.

See Sheriff's Meadow Foundation Inc. v. Bay-Courte Edgartown Inc., 401 Mass. 267 , 269 (1987). Because the title Mr. Owens claims is record title, he must prove a clear and unbroken chain of ownership back to a solid source. See Bongaards v. Millen, 440 Mass. 10 , 15 (2003) (where grantor lacks title "a mutual intent to convey and receive title to the property is beside the point. The purported conveyance is a nullity, notwithstanding the parties' intent."). This case turns on whether he has met that burden of proof.

The inquiry thus begins with Mr. Owens' deed, and then works backwards to see what land that deed contains, if any. [Note 5] For purposes of this case, it only matters if that land is in the location shown on Ex 1. If it is not in that location (or, more precisely, if Mr. Owens is unable to prove that it is located there), then this case must be dismissed. Land located elsewhere is irrelevant to the ultimate issue presented (the easement).

Mr. Owens contends that the land shown on Ex. 1 is the second parcel in his deed, [Note 6] which is described as "a certain piece of woodland bounded as follows:

[1] On the East by land now or formerly of Edmond Flinn,

[2] On the South by a ditch, [Note 7] and

[3] On [t]he West by a road. [Note 8] Containing an area of about two acres."

No other information about the parcel is contained in the deed and, in a notable omission, no northern boundary is identified.

Mr. Owens hired a surveyor, Donald Poole, to locate this parcel "on the ground" and the survey Mr. Poole produced (Ex. 1, labelled "Plan of Land in Harwich MA off Queen Anne Road and Oyster Pond Road as claimed by KMA Realty Trust" (June 9, 2004)), was recorded at the Registry by Mr. Owens in Plan Book 592, Page 33 (Jul. 14, 2004). How Mr. Poole took the three-sided description in the Owens deed and decided that the parcel it described was the five-sided lot he depicted in Ex. 1, with those precise bounds, bearings, and measurements, was neither explained nor apparent in the evidence. [Note 9] Unlike plans of registered land which are produced in connection with land registration proceedings, see G.L. c. 185, §26 et seq., recorded plans such as Mr. Poole's do nothing more than reflect a claim of ownership unless and until reviewed and approved after due court proceedings.

The description in Mr. Owens' deed first appeared in an April 9, 1894 deed from the children of Oren Eldridge ("Oren Sr.") to one of their siblings, Oren H. Eldridge ("Oren H.") [Note 10]

- a deed not recorded until October 14, 1941. [Note 11] With some variation, that language remained consistent from deed to deed thereafter, up to and including Mr. Owens'. [Note 12] Like the 1894 deed, each of these deeds lacked any identification of the parcel's northern boundary, or anything more specific about the other ones. If this problem was recognized (and how could it not have been?), nothing was done about it. This was likely because the parcel (vacant, landlocked woodland, never developed) had little, if any, value at that time. As noted in Cuddy, Cape Cod woodlots had steadily declining value in the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, and these were no exception. The three woodlots in Oren H.'s estate, four acres in total, were valued at only $40 in 1941. There is no indication that any use was ever made of them (they were not among the parcels identified as "cleared" or "meadow" in Oren Sr.'s 1883 estate inventory). And to say that their documentation was "relaxed" (deeds not recorded for years; a missing northern boundary; no attempt made to give the parcel's other boundaries a better description or to install "on the ground" monumentation) is an understatement. See Cuddy, 2017 WL 2687415 at *2.

There are no deeds prior to 1894 that have the Owens description - none, at least, into Oren Sr. - so Mr. Owens makes a leap and argues the 1894 deed must be for the same two acre parcel that was conveyed from Amos Eldridge to Oren Sr. by deed dated February 22, 1854. [Note 13] This 1854 deed is thus the source of title upon which Mr. Owens relies - the so-called "starting deed" to which his title must connect, and which, for his ownership claim underpinning his alleged easement to succeed, must be in the location he claims. There is nothing in Oren Sr.'s estate inventory that is helpful to the resolution of this question, [Note 14] so everything depends upon the 1854 deed itself and whatever information can be gleaned from the title histories and abutter references for the other properties in the area.

The property in the 1854 deed is described as "A certain piece of scrub land situated in Harwich & bounded as follows, viz:

Beginning at the South West corner of the premises, at a stake & stone by the road, thence runs

[1] Northerly in Jacob Smith's range to a stake & stone by Edmund Flinn's range, thence

[2] Easterly by said Flynn's range to a stake & stone on a ditch, thence

[3] Southerly by the ditch to the road to a stake & stones, thence

[4] by the road to the first mentioned bound, being two acres between same more or less."

The parties agree that this description and the description in the 1894 and Owens deeds have no common or corresponding bounds." [Note 15] Both state that the properties they describe are in Harwich and contain approximately two acres, but thereafter the differences are striking. First, the 1854 deed references specific monuments - "stake[s] & stone[s]" - at each of the parcel corners. But neither the 1894 deed nor any of the intervening deeds between the 1894 and Owens deeds mention any such monuments, nor does Mr. Poole's plan indicate that any were

found during the course of his fieldwork. See Ex. 1. The failure to find even traces of these monuments is notable because the land in this area has remained undeveloped and undisturbed from 1854 to the present. One would have expected at least some traces to be there if this was, in fact, the same parcel. Second, the western boundary in the 1854 deed is land owned by Jacob Smith, not (as the 1894 and Owens deeds state) a road. Third, the 1854 deed has a northern boundary (land owned Edmund Flinn), while the 1894 and Owens deeds describe no boundary on the north at all. Fourth, the eastern boundary in the 1854 deed is a ditch, ending at a road, while the eastern boundary of the 1894 and Owens deeds is "land now or formerly of Edmund Flinn." And fifth, the southern boundary in the 1854 deed is a road, not (as the 1894 and Owens deeds states) a ditch.

Aligning the 1854 and the 1894 and Owens deeds in an effort to have them describe the same parcel requires pivoting the 1854 deed so that its northern boundary (Edmund Flinn/Flynn) becomes its eastern one, its eastern boundary (a ditch) becomes its southern one, its southern boundary (a road) becomes its western one, and its western boundary (Jacob Smith) becomes its northern boundary. There are many problems with such a pivot, however. Among those problems are these. First, compass directions were the same in 1854 as in 1894 (north is still north, not east) and conveyancers would have been careful to keep directional references consistent deed to deed if the same property was being conveyed. Second, the lack of any mention of Jacob Smith in the 1894 deed as an abutter (now or formerly) on any side of that parcel is significant. If the 1894 parcel was the same as the 1854 parcel, surely such a reference would have been made. Third, as other deeds in the evidentiary record showed, Jacob Smith could not have been a northern abutter as the pivot requires. His land in this area was to the west. Fourth, the north/south cartpath which Mr. Owens alleges is the same "road" both deeds must have intended to reference as their western boundary is not the only cartpath in this area. As shown by other evidence in the record, there was at least one east/west cartpath through these woods that would have been consistent with the 1854 deed's reference to it as a southern boundary, and thus a strong indication that the 1854 deed describes a different parcel than Mr. Owens'. Fifth, the lack of any northern boundary at all in the 1894 deed and the ones following from it cannot be ignored. If, as Mr. Owens seems to suggest, Edmund Flinn was the northern as well as the eastern abutter in the 1894 deed (thus filling that gap), why did the drafters not say so, either in the 1894 deed or in even one of the successor deeds? As noted above, the drafters could not possibly have failed to note the absence of such a boundary. If they were so uncertain as to where the parcel was located, this court should be cautious of reaching such a certainty on its own.

Mr. Owens' response to these objections is this. The 1854 deed put the property it described into Oren Sr.'s ownership. There is no deed of record in which he conveyed that property to anyone else during his lifetime. [Note 16] The only conveyance out of his estate of anything likely to be this property (a two-acre parcel of vacant woodland in Harwich with a road, a ditch, and Edmund Flinn as named abutters) is the 1894 deed from the Eldridge children (Oren Sr.'s heirs) to their sibling, Oren H. Therefore, says Mr. Owens, it simply must be the same two-acre parcel. [Note 17] He concedes that it may not match up to the precise location, bounds, bearings, and measurements that Mr. Poole depicted on Ex. 1, but argues that, for purposes of giving him standing to assert an easement over the traces of the cartpath, all that needs to be determined is that he owns two-acres bounded on one side by that path.

I cannot, however, reach that conclusion on the record before me. Mr. Owens has the burden of proof and, for the reasons noted above, he has not met it. The Association and its title expert have made a plausible case that the two acres owned by Mr. Owens are in a different location entirely [Note 18] and, while (as Mr. Owens notes) there are problems with the Association's theory, this is not a case where all Mr. Owens need do is show that his theory is better. Rather, he must prove ownership, not just a better case, and he has not done so on this record. See Sheriff's Meadow Foundation, 401 Mass. at 269.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the plaintiff's complaint is DISMISSED. Because the dismissal is based on the plaintiff's failure to prove title and not because any superior title has been proved, the dismissal is without prejudice. If more and better proof is obtained, and if all potentially affected abutting landowners are joined as parties, the plaintiff may re-assert its title claims in a future lawsuit. At the end of the day however, in the absence of such proof, it may be one of those instances that only title by adverse possession can resolve.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

Exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The alleged easement also runs through land owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a parcel Mr. Poole's plan marks "n/f Robert Eldridge, but which the Town's tax records mark "owners unknown." For now, only the Association has been named as a defendant in this case.

[Note 2] Mr. Owens and the Association would be bound by the adjudication of that issue, but non-parties, unless in privity with a party, would not be bound. See Cruickshank v. MAPFRE USA, 94 Mass. App. Ct. 662 , 665 (2019).

[Note 3] The parcel is vacant forest land surrounded by vacant forest land, much of it owned by the Commonwealth.

[Note 4] See Cuddy v. Eldredge Public Library, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 1129 (2017), 2017 WL 2687415 at *2 (evaluation of which calls in which deeds are more reliable is "a factual determination for the judge to make in light of the circumstances, which included (as the judge noted) the relaxed documentation practices concerning woodlots on Cape Cod in the past (and particularly during the nineteenth century as their value declined), the absence of reliable or complete monumentation, the trial testimony [of the witnesses], the loss of documents resulting from the 1827 destruction by fire of the Barnstable County registry of deeds, and - of particular importance [in the Cuddy case] - the history of the various transfers, as well as the points in time at which, and the identities of the parties among whom, they occurred.").

[Note 5] Just because a deed purports to convey something does not mean that it actually does so. Unless the grantor actually owns the land he purports to convey (or, under the doctrine of estoppel by deed, soon acquires that land, see Zayka v. Giambro, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 748 , 751 (1992)), nothing is conveyed. See Bongaards, 440 Mass. at 15.

[Note 6] Barnstable Registry of Deeds Book 12981, Page 14, Parcel 2 (May 1, 2000).

[Note 7] The abutting landowner is not named, nor is any information provided about the ditch.

[Note 8] The road is neither named nor described, nor is any information about it provided - for example, where it comes from, or where it goes to.

[Note 9] When questioned by the court at oral argument, Mr. Owens' counsel gave the following account of how the plan was created. According to that explanation, everything is based on three assumptions.

First, Mr. Poole assumed that the "vehicle tracks and path" he observed and noted on the plan were the "road" referenced in the Owens deed, and that the western boundary of the parcel followed the mid-point of that "road" as he interpreted its location must have been (the area is overgrown, and whether something on the ground is a "vehicle track" or not is a matter of interpretation). Second, although Mr. Poole did not find a ditch or even traces of a ditch on the south (note that none is indicated on the plan), he assumed that two concrete bounds he found in that area must mark where a ditch had been, even though no deed in evidence in this case (Mr. Owens' or any other) so indicates. Third, he assumed that two acres was the exact size of the parcel and, using the easternmost of the concrete bounds as the southeast corner of the lot, drew the other boundary lines so that they enclosed two acres (an "adjust to fit" approach), which is why a fifth boundary line was needed north of the "road" to give the parcel sufficient area. See Ex. 1.

All of the monuments along these "adjust to fit" lines (marked on the plan as "hub and tack set") were put there by Mr. Poole himself. The ownership of the land to the north and west of the parcel - all landlocked vacant forestland, surrounded by landlocked vacant forestland - is marked "owners unknown" on the town's tax records, so it seems unlikely that any of those owners were consulted on the location of those boundaries. It is also unclear what (if any) consultation was made with the Commonwealth on the location of the boundary lines to the east and south. In short, what appears to be a precise survey of an actual parcel is nothing of the kind. It is, as Mr. Poole was careful to state, nothing more than a plan of land "as claimed" by Mr. Owens in his capacity as trustee of the KMA Realty Trust). See Ex. 1 (emphasis added).

[Note 10] The 1894 deed listed the same three parcels, using substantially the same descriptions, as the Owens deed, and the property at issue is the second parcel in each. The only difference between the 1894 deed and the Owens deed in their description of that parcel is that the eastern boundary, rather than being "by land now or formerly of Edmond Flinn" (Mr. Owens' deed), was "by Edmond Flinn" in the 1894 deed, presumably reflecting that Mr. Flinn was alive in 1894.

[Note 11] Oren H. Eldridge never recorded that deed himself, nor was it recorded at any time during his lifetime. Instead, it was recorded some 47 years later, after his death, by his personal representative who recorded it simultaneously with the filing of Mr. Eldridge's estate inventory in the Barnstable Probate Court. In that inventory these two acres, lumped together with two other parcels each identified as one acre in size, were described as "old swamp land in East Harwich, 4 acres, approx.." and valued in total at $40. The Eldridge inventory contained many other parcels of land in Harwich, some described as "swamp" or "rough swamp" and others simply as "lots." The remainder of his real property was apparently in Chatham - the town where he resided.

[Note 12] The land is called "swamp land" in some of the intervening deeds, and "woodland" in others. The most significant variation is its description in an estate inventory as "land on Hawkes Nest Road" - an actual road in Harwich over a thousand feet to the east of the land shown on Ex. 1.

[Note 13] The deed was recorded six years later in Book 74, Page 258 (Apr. 10, 1860).

[Note 14] His real property at the time of his death was listed as: (1) "Dwelling House, Barn and Outbuildings $600," (2) "Homestead Land $60," (3) "Cleared Land and Meadow $84," and (4) "Wood Land $120."

[Note 15] Joint Statement of Facts at 2, ¶7.

[Note 16] This would not rule out an unrecorded deed, however.

[Note 17] See Brief of Plaintiff KMA Realty Trust in Support of Title at 7 ("While the deed description did vary over the course of the numerous conveyances amongst the Eldridge family, there is no indication that it was not the same parcel being conveyed.").

[Note 18] See Affidavit of Paul O'Connell III in Opposition to Plaintiff's Title Examination and Brief of the Plaintiff KMA Realty Trust in Support of Title. In addition to the problems with Mr. Owens' ownership discussed in this Decision (the lack of a persuasive match between the 1854 deed and the 1894 deed, indicating that the two described different parcels), the Association points to an additional issue. So far as the record shows, there are no deeds into Amos Eldredge that facially contain this two acre parcel, nor are there any deeds or documents of record naming Amos as an abutter to any parcels in the area. Moreover, the evidence showed that Eldridge family members owned many, many parcels of woodland in Harwich. The 1854 and 1894 deeds each went unrecorded for many years - this was landlocked woodland without much value, with no one seemingly paying it much attention - and it would not be surprising if there are missing, unrecorded deeds relating to this land. See Brief of the Plaintiff KMA Realty Trust In Support of Title at 9 (arguing, in response to the Association's challenge to its title claims, "These issues are distinguishable from any inconsistent deed descriptions in the Plaintiff's chain of title and leads to the conclusions [sic, conclusion] that there may in fact be a missing deed.").

DAVID OWENS as trustee of the KMA REALTY TRUST vs. OYSTER POND HOMEOWNERS' ASSOCIATION TRUST

DAVID OWENS as trustee of the KMA REALTY TRUST vs. OYSTER POND HOMEOWNERS' ASSOCIATION TRUST