WASHINGTON MILLS APARTMENTS II L.P. v. ANDREA MANAGEMENT CORP.

WASHINGTON MILLS APARTMENTS II L.P. v. ANDREA MANAGEMENT CORP.

MISC 16-000749

July 26, 2019

Essex, ss.

LONG, J.

WASHINGTON MILLS APARTMENTS II L.P. v. ANDREA MANAGEMENT CORP.

WASHINGTON MILLS APARTMENTS II L.P. v. ANDREA MANAGEMENT CORP.

LONG, J.

Introduction

Plaintiff Washington Mills Apartments II L.P. and defendant Andrea Management Corp. are abutting landowners on an island in Lawrence between the North Canal and the Merrimack River Andrea at #250 Canal Street (accessed by bridges over the canal) and Washington at #240 (directly behind the Andrea property, and accessed over the canal by the same bridges). Both properties, in common ownership until 1948, were once part of a single textile mill complex. Andrea's property is the former Mill Building No. 7. Washington's is the former Building No. 6 (still standing), Building No. 6 East Wing (now demolished), a former turbine house (now demolished), a former boiler house (now demolished), and a former exhaust stack (now demolished). Other parts of the mill were on adjacent sites on the island, now separately owned.

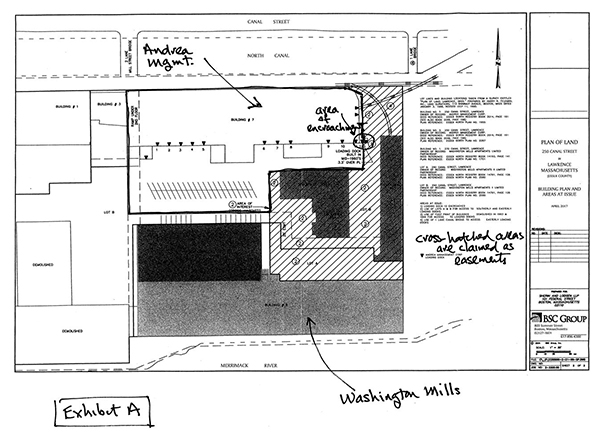

The days when the mill was active are long gone, and its former structures have either been demolished or re-purposed to other uses. Washington, which recently purchased the #240 Canal Street site, wants to fence it off for development and, in this action, seeks a judgment declaring that it owns the property free and clear of any adverse claims by Andrea. Andrea makes two such claims. The first is an adverse possession claim to approximately 3.3' of Washington's record land on which Andrea's predecessor built a loading dock addition in the mid-1960's. [Note 1] The second is an easement claim express and, if that fails, prescriptive to the routes Andrea's trucks take over the Washington site when they drive to and from the twelve loading docks along the back side of Andrea's building. See Ex. A (attached). Andrea also claims that Washington, which has an express easement across part of Andrea's land, [Note 2] has "overburdened" that easement by permitting third parties occupying unbenefited properties to use it as well.

It is unclear if the "overburdening" claim is currently being pressed. [Note 3] In any event, the third-parties allegedly using Washington's easement have not been made parties to this case and actual damages from their past use, if any, have not to date been shown or quantified. Rather, the case has focused, and is ready for trial, on the adverse possession and easement claims asserted by Andrea.

Washington contends that those claims can be dismissed on summary judgment and has so moved. With respect to Andrea's express easement claim arising, Andrea says, from the same 1948 deed that created Washington's Washington asserts that that deed unambiguously refutes such an easement. With respect to Andrea's claims of adverse possession and prescriptive easement, Washington contends all such uses of its land were permissive, not adverse, causing those claims to fail. Andrea, not surprisingly, disagrees.

At the end of the day, Washington may succeed in showing that Andrea's adverse possession and easement claims are invalid or, in the case of the alleged prescriptive easement, far less than the area claimed. [Note 4] But this is not that day. Contrary to its arguments, genuine issues of material fact exist on all these claims that require trial, and the outcome of the case depends upon how those factual issues ultimately are resolved. Washington's motion for summary judgment is thus DENIED.

Discussion

The standard for granting summary judgment is a strict one. It may be granted if, but only if, after "viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law." Augat Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co, 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991). All genuinely disputed facts must be construed in favor of the opposing party and, even if those facts are not disputed but reasonable inferences from them can be drawn either way, those inferences must favor the opposing party. See Verdrager v. Mintz Levin Cohn Ferris Glovsky & Popeo P.C., 474 Mass. 382 , 395 (2016). By this standard, as discussed more fully below, Washington's motion must be denied.

Moreover, even if summary judgment might otherwise be warranted, the court has discretion to deny it if it deems that the issues should be further developed before being decided. See Phelps v. MacIntyre, 397 Mass. 459 , 461 (1986). This is such a case, and I deny Washington's motion on this basis as well.

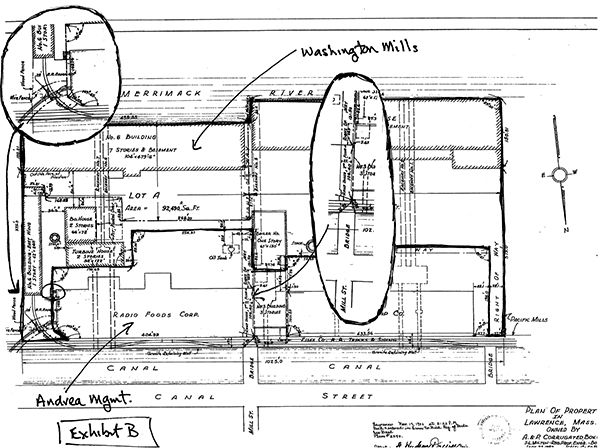

Two graphics are helpful in understanding the parties' positions. The first a plan showing Andrea's claims is attached as Ex. A. [Note 5] The 3.3' building extension claimed by adverse possession is circled and labelled "area of encroachment," and the areas over which Andrea asserts easement rights are cross-hatched. See Ex. A. Andrea's express easement claims are based on the 1948 deed which split the parties' parcels. A 1952 plan, showing the areas referenced in that 1948 deed, is attached as Ex. B. [Note 6]

Express Easement

Andrea bases its "express easement" claim on the 1948 deed its predecessor received from the parties' common grantor, Plymold Corporation, [Note 7] which owned (and was retaining) the Washington site at that time. That deed included "the following rights, so far as the grantor may legally grant the same": [Note 8]

(a) to use in common with the grantor and others entitled thereto said way twenty five feet wide along the south side of said [North] Canal; [Note 9] the bridges across said Canal serving the granted premises and land retained by the grantor; [Note 10] and Canal Street along the north side of said Canal;

(b) to use in common with the grantor and others entitled thereto the railroad sidings now serving the granted premises, and to use for the purpose of construction, operation, use and maintenance of railroad sidings the strip of land twenty eight feet wide marked on said plan "28' Railroad Easement" [Note 11] and running northeast from the easternmost bound of the granted premises to the east bound of land retained by the grantor;

(c) to use in common with the grantor and others entitled thereto the present power lines across the Merrimack River from land retained by the grantor, and to have and maintain, if necessary, power lines across land retained by the grantor between the granted premises and said river, the words "power lines" to include telephone lines;

(d) to use and maintain existing water supply facilities, sewers and other facilities serving the granted premises, such use and maintenance to be in common with the grantor insofar as said facilities serve in common the granted premises and the premises retained by the grantor;

(e) to enter upon the premises retained by the grantor in order to obtain full benefit of the rights herein granted.

Deed, Plymold Corporation to Radio Foods Corporation (Oct. 6, 1948), confirmed by the referee in bankruptcy and recorded November 5, 1948.

According to Andrea, its express easement to drive over the Washington property to get to the loading docks at the rear of its building derives from ¶ (e). It concedes that nothing in (e) explicitly says that in so many words, nor (at least easily) that such an easement can be based on "necessity", [Note 12] but points to three things that, it says, support its claim.

The first is its allegation not contested by Washington for purposes of this motion that, both before and after the 1948 deed, trucks going to and from the Andrea site regularly used the areas Andrea now claims, except for those that were occupied by buildings at that time. [Note 13] See Ex. A. This, it says, is both an "attendant circumstance" to the deed (the use before) [Note 14] and a demonstration of how the parties intended the deed to be interpreted (the use after). [Note 15]

The second is the easement over Andrea's land, granted in the same deed, for access to the Washington site. This was:

(b) to use in common with the grantee for passing and repassing, with motor vehicles or otherwise, the ramp under the second floor at the west end of said No. 7 Mill, the vertical rising gate at the north end of said ramp, and the strip of land running southerly from said ramp to the southernmost bound of the granted premises and marked on said plan "Right of Way retained by Plymold Corporation"; [Note 16] [and]

* * *

(g) to enter upon the granted premises in order to obtain full benefit of the reservations herein made.

Andrea sees this as an intended general right of access, and the use of the parallel phrase in Andrea's grant in ¶(e) ("to enter upon the premises retained by the grantor in order to obtain full benefit of the rights herein granted") as indicative of an intent to make both sets of access rights (Andrea's and Washington's) "reciprocal" in nature. See Affidavit of Edward A. Rainen, Esq. (Jun. 3, 2019). [Note 17]

Its third argument focuses on the purchase and sale agreement between Plymold and Andrea's predecessor, Radio Foods Corp. which culminated in the 1948 deed, and the language in that agreement that "the parties hereby agree that they shall grant to each other the right to enter upon the premises of each other in order to obtain full benefit of the grants and reservations made herein" language which, Andrea contends, once again indicates an intent to have both sets of access rights "reciprocal." See Rainen Aff.

The problem with these arguments is this. Both the purchase and sale agreement and the deed reflect easement rights to Andrea, to be sure, but the ones granted to Andrea as enumerated in the deed (¶¶ (a)-(d)) and in the agreement (pp. 2-3) are specific, are the same, and none describes an easement for general access via the route now claimed by Andrea. Rather, the only easement described for that area (labelled "28' R.R. Easement" on the plan, see Ex. B) is "for the purpose of construction, operation, use and maintenance of railroad sidings." Nothing is said about general access or a general right of way in that area (or, for that matter, in any other area retained by Plymold) for Andrea's benefit. Moreover, the purchase and sale agreement states that the plan accompanying it, incorporated by reference into the agreement, "sets forth the bounds, together with the rights of ways, grants and reservations" to be granted, and no right of way is shown on that plan in the area claimed by Andrea, just the railroad easement. The question then becomes whether these specific enumerations, preceding the language in ¶ (e), control the interpretation of (e) and thus preclude the inference that (e) was intended to be a general access grant. [Note 18] Washington says "yes" it does preclude that inference and its position is aided further by the requirement that an express easement "must identify with reasonable certainty the easement created and the dominant and servient tenements." Parkinson v. Assessors of Medfield, 395 Mass. 643 , 645 (1985), S.C., 398 Mass. 112 (1986), quoting Dunlap Investors Ltd. v. Hogan, 133 Ariz. 130, 132 (1982). No such identification is made, at least expressly, in the grant to Andrea.

Andrea thus has an uphill battle to show an express easement, [Note 19] but the arguments it makes are not unreasonable and thus cannot be ruled out on summary judgment. [Note 20] In any event, as a matter of discretion, I will not rule them out at this stage of the proceedings without hearing Andrea's title expert, attorney Edward Rainen, in full. As the Supreme Judicial Court has noted, maxims such as the expression of one thing being implied exclusions of others are not rules of law, but simply aids to interpretation and not to be applied when to do so would frustrate an instrument's intent. See Bank of America v. Rosa, 466 Mass. 613 , 619-620 (2013). After listening to the fact witnesses and reviewing what they have to say of the history of use of these parcels, it may very well be as Mr. Rainen says: the omission of explicit language in the deed may simply have been the result of the parties' assumption that it wasn't needed a reciprocal understanding that the access that existed then would continue to be the access thereafter. I still wonder about the wire fence, though. [Note 21]

Adverse Possession and Prescriptive Easement

For purposes of its motion, Washington does not dispute the 3.3' building encroachment, the past use of the alleged easement area by Andrea's and its predecessors' trucks, the area of the easement claimed, that the encroachment and use have been open, notorious and continuous for twenty years or more, nor any of the other elements of adverse possession or prescriptive easement, [Note 22] except for one the requirement of adversity. Rather, it contends that all such occupation and use was by permission, and relies on the testimony of Arthur Theriault and the rulings in Stearns v. Risso, 2019 WL 1526860 (Mass. Land Ct. 2019), to support that contention. A longtime continuous use such as this, spanning more than twenty years, triggers the presumption that the use was nonpermissive. See Smaland Beach Ass'n v. Genova, 94 Mass. App. Ct. 106 , 115 (2018). "Once the presumption arises, the landowner has the burden of rebutting it by showing that the use was permissive." Daley v. Swampscott, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 822 , 827 (1981).

Mr. Theriault, whose knowledge dates back to 1952, gave testimony that supports Washington's contention of permission. But he did so in response to leading questions, leaving it unclear what he actually intended to mean when he responded to Washington's use of that word. Moreover, he did not identify the basis of his response who, exactly, said what; who, exactly, did what; when; and in whose presence and why he concluded (if, in fact, he did) that that meant the use was permissive rather than adverse. What he testified he observed is just as consistent with acquiescence which does not negate adversity, see Ivons-Nispel Inc. v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 763 (1964) as it is permission, and needs further development to discern which of the two it was. This is one of those cases, centering on an issue (permission or acquiescence) which could go either way, where listening to the witnesses, observing them as they testify, getting as many details as possible, and then considering the entirety of their testimony in context, will be vitally important. See, e.g. Moon Owl Realty LLC v. Hubbard, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 90 Mass. App. Ct. 1114 (2016), 2016 WL 6565934. The Stearns case, for example, upon which Washington chiefly relies, was decided only after trial, with the benefit of having seen and heard the witnesses and then evaluating what they said.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, plaintiff Washington Mills Apartments II L.P.'s motion for summary judgment is DENIED.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] A 1952 plan shows the area occupied by an exterior staircase serving Building 7.

[Note 2] The easement, set forth as a reservation in the 1948 deed that split the parcels, grants Washington access to its property through the ramp under the Andrea building and then along a designated right-of-way. See Ex. B. The ramp connects to the Mill Street Bridge over the canal.

[Note 3] Washington denies that it has given permission to any such third parties, presumably an assertion that, to the extent those third parties are crossing Andrea's property (Iron Mountain was mentioned as one), they are doing so entirely on their own and are solely accountable for such use.

[Note 4] "To establish a way by prescription, the use must be not only open, adverse, uninterrupted, peaceable, continuous and under a claim of right, but must be confined substantially to the same route, and to substantially the same purpose for which the way was designed originally, unless the way is one for all purposes." Hoyt v. Kennedy, 170 Mass. 54 , 56-57 (1898). Later cases have made plain that the "claim of right" need not be made expressly or with such an intent, but is presumed from the use itself "whether that use is sufficient to put a reasonable owner on notice of the hostile activity and thus afford the owner an opportunity to act to vindicate his or her rights." AM Properties LLC v. J&W Summit Ave. LLC, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 150 , 157 (2017).

[Note 5] Andrea's property is Building No. 7 and the marked area around it. Washington's property is Building No. 6 and the area marked around it, including the cross-hatched section over which Andrea claims easement rights.

[Note 6] Andrea's property is labelled Radio Foods Corp. (its owner at that time). Washington's is the No. 6 Building and the other structures (now demolished) within its property line.

[Note 7] More precisely, the deed came from the U.S. District Court, District of Massachusetts, in which Plymold's Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings were taking place.

[Note 8] Successor owners are entitled to all non-abandoned, non-extinguished easement rights contained in their predecessors' deeds even if not enumerated or mentioned in their own deeds, "either generally or specifically." See G.L. c. 183, §15.

[Note 9] This is a reference to the area occupied by the railroad tracks running along the south (island) side of North Canal. See Ex. B ("Essex Co. R.R. Tracks & Siding").

[Note 10] There are two such bridges: the "2 Lane Mill Street Bridge" on the west side of Building No. 7, and the "1 Lane Bridge" on the building's east side. See Ex. A.

The 2 Lane Mill St. Bridge leads to a ramp under the second floor on the west side of the Andrea building and provides access to the Andrea Management site via that ramp. By express reservation in the 1948 deed, Plymold (and now Washington) has an easement to access its site across Andrea's land via that ramp and the areas marked "right of way" on Ex. B.

The 1 Lane Bridge on the east side of the Andrea building leads to a corridor owned by Washington (the area on Ex. B labelled "28' R.R. Easement') which is criss-crossed by railroad sidings as shown on that plan, one to the former "No. 6 Building-East Wing" on land owned by Washington, and the other to Andrea's building, then owned by Radio Foods Corp. Interestingly, the plan shows a wire fence which would seem to block access to the rear of the Andrea building (and to the Washington site as well) from that direction. Given that the plan shows a railroad siding leading through that fence, however, it likely had a gate for trains and, perhaps, for vehicles as well. Under the summary judgment standard, Andrea gets the benefit of that inference.

[Note 11] See Ex. B, showing the area so indicated.

[Note 12] When parcels are split leaving one "landlocked," an access easement over the retained land is deemed to arise by necessity. See Town of Bedford v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 76-77 (2004). The Andrea parcel has another means of access (across the 2 Lane Mill Street Bridge and then through the ramp under the second floor (see Ex A), but Andrea contends that that was not sufficient for the uses of the building at that time (nor this), presumably because of truck size and turning radius. See Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 105 (1933) (necessity that gives rise to easement rights need not be an absolute physical necessity, yet it must be a reasonable necessity). Because I deny summary judgment on other grounds, I need not and do not decide this question.

[Note 13] For purposes of this motion, Washington does not dispute that trucks going to and from Andrea's loading docks regularly used the route. It contends, however, that all such use was permissive. As more fully discussed below, whether the use was permissive or not is a genuinely disputed material fact. For purposes of this motion, I thus presume that all of it was adverse.

[Note 14] See Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007) (Where an easement is created by deed, its meaning, "'derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances.'") (quoting Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998)).

[Note 15] See Martino v. First Nat'l Bank of Boston, 361 Mass. 325 , 332 (1972) ("There is no surer way to find out what parties meant, than to see what they have done.") (internal citation and quotation omitted).

[Note 16] See Ex. B, where the areas are labelled "ramp under 2nd floor" and "right of way", and are on the land being conveyed to Andrea's predecessor in title.

[Note 17] Attorney Rainen (Andrea's expert witness) is a conveyancer and title examiner with over forty years' experience in the specialty.

[Note 18] The doctrine is known by its latin phrase, "expressio unius est exclusio alterius."

[Note 19] The party asserting an easement has the burden of proving it. See Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 757 (1945).

[Note 20] I note, for example, that ¶ (a) in its grant gives it the right "to use [,] in common with the grantor and others entitled thereto [,] the bridges across said Canal serving the granted premises and land retained by the grantor " (emphasis added). From that plural reference ("bridges"), which clearly includes the "1 Lane Bridge" that leads to the access route Andrea claims (see Ex. A), it is not unreasonable to infer an intent for Andrea to have a general right of access over that bridge and through the area it leads to. See, e.g., MacLean v. Conservation Comm'n of Nantucket, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 93 Mass. App. Ct. 1108 (2018), 2018 WL 1997061 at *1-*2, where the Appeals Court found deed language ambiguous, and thus requiring extrinsic evidence to determine its meaning, even though all parties in that case contended that there was no ambiguity in the deed language at all.

[Note 21] See n. 10, supra.

[Note 22] See n. 4, supra. Adverse possession has the same elements as easements by prescription, with this difference. For adverse possession to occur, the occupation must be exclusive. See Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007).