SANDRA JACKSON v. ADAM BARNEY and PAULA BARNEY

SANDRA JACKSON v. ADAM BARNEY and PAULA BARNEY

MISC 17-000541

October 28, 2019

Suffolk, ss.

LONG, J.

SANDRA JACKSON v. ADAM BARNEY and PAULA BARNEY

SANDRA JACKSON v. ADAM BARNEY and PAULA BARNEY

LONG, J.

Introduction

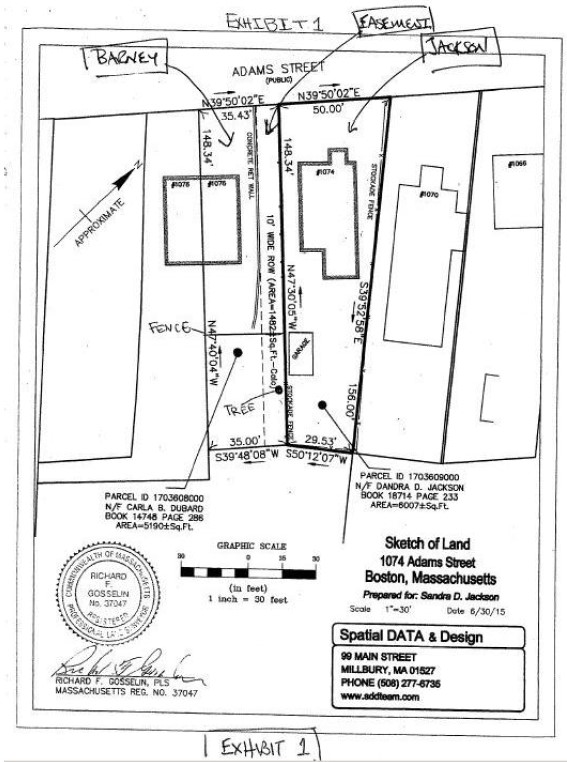

Plaintiff Sandra Jackson, who owns and lives at #1074 Adams Street in Dorchester, has an express ten foot-wide right-of-way easement over the property next door at #1076, currently owned by defendants Adam and Paula Barney. The easement starts at the street and extends the full length of their common boundary line to the back of their lots. See Ex. 1 (attached).

The easement was created in 1947 by the then-common owner of both properties when he split off and sold the now-Barney land and, in that deed, expressly reserved the right-of-way over that land for the benefit of the lot he retained, now owned by Ms. Jackson. It has explicitly been referenced in every succeeding deed of the Barney property, including the deed to the Barneys, and its intent is not hard to discern. It was, and is, to give the Jackson property vehicle access over the right-of-way to the area behind the Jackson house where Ms. Jackson's garage and off-street parking are located. All of Ms. Jackson's back yard is paved, and she and her visitors park in that entire area.

The right-of-way is currently paved as far as the line of the front (street side) edge of Ms. Jackson's garage. Prior owners of the Barney property installed a fence across the right-of-way at that point, blocking its use beyond the fence. See Ex. 1. There is also a tall tree, decades old, in the easement area behind the fence close to the back end of Ms. Jackson's garage, which cannot be gotten past or maneuvered around while staying within the easement. See id. It too totally blocks the easement beyond its location.

Neither the fence nor the tree was an issue for Ms. Jackson - they have been there longer than she has - at least until recently. The Barneys bought #1076 in December 2015 and, based on false representations by its prior owners, believed that they could park in the front part of the easement. Accordingly, they began parking their two cars, tandem fashion (nose to bumper), in front of the fence. In addition, contractors and others coming to their house would also park there, sometimes even further towards the street. Ms. Jackson asked the Barneys to cease such parking, they refused, and Ms. Jackson then brought this lawsuit, initially through counsel but now, because she does not have enough money to continue paying her attorney, pro se.

Ms. Jackson seeks the removal of the fence and the tree, a permanent injunction giving her full, unobstructed use of the entirety of the right-of-way at all times (i.e., no parked cars or other obstructions anywhere along its length), and monetary damages. The Barneys oppose those requests, contending that the area behind their two cars when they are parked in tandem with the nose of the first at the fence is all that is needed to give Ms. Jackson "convenient access" over the right-of-way to her garage and back yard parking, and thus all to which she is entitled. See Martin v. Simmons Properties LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 14-15 (2014). They also contend that she has abandoned all but that part of the easement. See Martin, 467 Mass. at 19. Ms. Jackson disagrees.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. I also took a view. [Note 1] Based on the stipulations, testimony, and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and my observations at the view, I find and rule as follows.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

As noted above, Ms. Jackson has a 10'-wide express easement over the Barney property, from the street to the back of their lots, directly abutting their common boundary line. See Ex. 1. [Note 2] Its clear purpose (it is described as a "right of way over driveway") is to provide vehicular access to Ms. Jackson's garage and back yard parking area, which occupies the whole of Ms. Jackson's back yard.

Two further aspects of the easement are also clear. First, Ms. Jackson is entitled to use the full 10' width of the easement, and has no obligation to drive on her own property to get to her garage or back yard unless she needs more than that 10' width to do so. See Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998) (easements construed in accordance with their plain language). Second, Ms. Jackson's house and garage have been in their current locations since at least 1933, well pre-dating the creation of the easement in 1947. [Note 3] The easement must thus be construed in light of those buildings and their locations - in other words, as intending reasonably smooth vehicular movements to and from the easement from the back yard parking area while maneuvering around the edges of the house and garage. See id. (construction of easement in light of "attendant circumstances"). Put simply, the house and the garage are fixed points which the easement was intended to accommodate, not to ignore, and anything in the easement that impedes reasonably smooth access to and from the garage and back yard parking area while maneuvering around the house and garage is inconsistent with the intent of the easement and thus not allowed. A vehicle might be able to get into or out of the back yard with multiple "back-ups" for example, but if those back-ups are due to anything in the easement itself - a parked car, say, or any other physical object - that car or object cannot be there.

The rear part of the easement has been blocked for many years by a fence across it on the line of the front of Ms. Jackson's garage. See Ex. 1. The easement has also been blocked for decades by a large tree behind the fence, 6 ½' back from the rear corner of Ms. Jackson's garage. [Note 4] See id. Even if the fence was not there, vehicles cannot get between the tree and the back of the garage to turn into or out of Ms. Jackson's parking area (there is not enough space), and they cannot get around that tree to its other side (and thus turn into or out of parking area from behind it) while staying in the easement. It is thus apparent, and I so find, that for decades no vehicle entering or exiting Ms. Jackson's backyard parking area has done so from anyplace other than in front of her garage.

After purchasing the #1076 Adams Street property in December 2015, the Barneys began parking their two cars in the front part of the easement, tandem fashion, with the nose of the first car against the fence and the nose of the second car directly behind the bumper of the first. [Note 5] Contractors working on their house, as well as occasional visitors, have parked even further into the front area of the easement, and in some instances on Ms. Jackson's property itself. When there are two cars parked in front of the fence, Ms. Jackson must drive onto her own property to get into and out of her backyard parking area.

A preliminary injunction in the case, entered before the court had the benefit of an actual view of the site, barred the parking of a second car but allowed one to be parked with its nose to the fence. [Note 6] A car was parked in that location at the time the view was taken, which allowed me to observe its effect on the use of the easement. [Note 7] As I observed at the view, it is not easy for vehicles to get into and out of Ms. Jackson's back yard with even one car parked in the easement, even with its nose against the fence. It is possible to get by a single car so parked, but it requires multiple maneuvers.

Prohibiting vehicles from parking on the street side of the fence will make turning into, and coming out of, Ms. Jackson's backyard parking area materially easier and more convenient for her and her visitors. As noted above, removing the fence will not result in any improvement, because the tree makes the fence barrier irrelevant and the tree has been there for decades. The fence is irrelevant because it is impossible for a vehicle to drive between the tree and the garage to turn into or drive out of Ms. Jackson's back yard (there is only 6 ½' between the back of the garage and the trunk of the tree), and it is impossible to drive past that tree to turn into Ms. Jackson's backyard while staying within the easement. Clearly no vehicle has done either since the tree was planted. All cars have turned into, and come out of, the backyard parking area by passing in front of the garage.

Further facts are set forth in the analysis section below.

Analysis

A party having the benefit of an express right-of-way, even if its location and dimensions are quite specific, does not necessarily have the right to use its entirety. Instead, unless the language of the easement requires that the full extent of the right-of-way be kept open, the easement holder is entitled only to a "convenient way" over the area for a "useful and proper purpose," and "not to unobstructed use of the whole space." Martin, 467 Mass. at 14-16 (internal citations and quotations omitted). That purpose is found by evaluating "the intention of the parties regarding the creation of the easement or right of way, determined from the language of the instruments when read in light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or [with] which they are chargeable to determine the existence and attributes of [the] right of way." Id. at 14 (internal citations and quotations omitted).

Here, both the language of the easement - in particular, its ten-foot width and its description as a driveway - and the physical conditions that existed at the time the easement was created (a house on the now-Jackson property, with its garage and parking in the rear), show that the purpose of the easement was to give the owners of the now-Jackson property an access route for vehicles over that right-of-way to the rear of the Jackson property. The question thus presented is how much of that right of way is needed for convenient access. Importantly for the analysis, because the right-of-way is expressly on the Barneys' land, none of that access route need be on Ms. Jackson's property. Even though her land on that side of her house is currently paved, she has the right to change that at any time she wishes, and to rely solely on the ten-foot easement over the Barneys' land for vehicle access to the rear of her property. Indeed, she testified that she intends to plant a garden alongside her house.

The reasonableness of a use of an express easement is a question of fact dependent on the circumstances of the case. See Doody v. Spurr, 315 Mass. 129 , 134 (1943). The evidence showed that a turn off of the easement into the area behind Ms. Jackson's house (and vice versa) is difficult, and perhaps impossible, if two cars are parked in tandem on the right-of-way in front of the fence. It is certainly not "convenient" if the second car is there. To squeeze between Ms. Jackson's house and the second car requires driving on Ms. Jackson's own land, which she has no obligation to do.

At the time the preliminary injunction was entered, I did not have the benefit of a view. Based solely on the materials submitted to me in connection with that motion, and as a preliminary ruling only, I found that if the second car was not there, Ms. Jackson could drive into and out of the rear of her property, using only the right-of-way easement, without undue difficulty. Having now seen the actual site and watched vehicles maneuvering on it, I find otherwise. Vehicles can get into and out of Ms. Jackson's back yard parking area with a car parked in the easement nose to the fence, and getting into that area is not materially impeded with a car there, but getting out of the rear area onto the easement (which generally involves backing-up) is a problem if there is a car in that part of the easement. [Note 8] It can be done, but it requires multiple back-ups whereas, if the car was not there, it can be accomplished in a single back-up maneuver. I thus find that parking a car in the easement in front of the fence, even a single car, is an unreasonable interference with Ms. Jackson's explicitly-granted easement rights. I further find that, if the easement is completely open and unobstructed in front of the fence, Ms. Jackson does not reasonably need any more of the easement (i.e. anything beyond the fence) to get into and out of her garage and rear yard parking area. In any event, Ms. Jackson and her predecessors have abandoned that back portion of the easement.

The fence across the easement, blocking off its back area, has been in place since before Ms. Jackson bought her property (1993). The tree behind the fence has been there even longer. No one could use that portion of the easement since they have been there and, prior to the filing of this lawsuit, there is no evidence that either Ms. Jackson or any of her predecessors ever protested their installation (the fence) or planting (the tree). "Nonuse does not of itself produce an abandonment no matter how long continued." Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 188 (1957). But non-use coupled with an intent to abandon does extinguish an easement, and abandonment "can be shown by acts indicating an intention never again to make use of the easement in question." Carlson [The 107 Manor Avenue LLC] [Note 9] v. Fontanella, et al., 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158 (2009), quoting Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 592 (1965); see generally, Restatement (Third) of Property, §7.4 (2000) cmt. a. There was evidence that the Barneys' predecessor owners would park in the easement area in front of the fence from time to time, but I credit Ms. Jackson's testimony that those cars would be moved when she requested, that she continued to use the entirety of that area to get to and from her rear yard, and that she never intended to abandon that area of the easement. But the easement area blocked off by the fence and the tree is a far different story. Abandonment can be inferred from a combination of physical obstructions making use of an easement impossible and a lack of objection over an extended period of time. See Carlson, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 158, citing Lund v. Cox, 281 Mass. 484 , 492-493 (1933); see also Sindler, 348 Mass. at 593 (abandonment found when alleged easement holders "stood by while the disputed area has been confined to the use of the owners of the locus during the past thirty-five years" and "apparently acquiesced in the construction of a high chain link fence which enclosed the disputed area for a few years, and in the subsequent placing of a chain across the entrance to the disputed area to prevent its use by persons other than those working or having business in the factory on the petitioner's premises."). This is precisely what occurred here, and I so find.

Conclusion

Ms. Jackson has an express easement over the area in front of the fence, the entirety of which she needs to ensure reasonably convenient access to her garage and back yard parking area as the easement intended. She has not abandoned any of that area, and is entitled to have it kept free and unobstructed at all times other than for brief "drop offs" and "pick-ups" by the Barneys, which I find would not unreasonably interfere with Ms. Jackson's easement rights. See Martin, 467 Mass. at 9 (servient estate "retains the right to make all uses of the land that do not unreasonably interfere with exercise of the rights granted by the servitude") (internal citations and quotations omitted). The easement area behind the fence has been abandoned, and Ms. Jackson has no right to use any of that area for any purpose.

Accordingly, the Barneys, their agents, servants, employees, contractors, invitees, and others acting in concert or participation with them are permanently ENJOINED from placing any objects or other obstructions in the front part of the easement (the area from the line of the fence to Adams Street) and from parking or stopping there other than for brief pick-ups and drop- offs. Ms. Jackson no longer has any right to use any portion of the back part of the easement (from the line of the fence to the back boundary line of the Barneys' lot), that portion of the easement is EXTINGUISHED, and Ms. Jackson is permanently ENJOINED from walking or driving there unless invited by the Barneys. Ms. Jackson's claim for monetary damages is DISMISSED WITH PREJUDICE for failure to prove any such damages.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

EXHIBIT 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] "Information properly acquired upon a view may properly be treated as evidence in the case." Martha's Vineyard Land Bank Comm'n v. Taylor, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 93 Mass. App. Ct. 1116 (2018), 2018 WL 3077223 at *2, n. 12 (internal citations and quotations omitted). See also Talmo v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Framingham, 93 Mass. App. Ct. 626 , 629 n. 5 (2018) and cases cited therein.

[Note 2] The easement is contained in a reservation in the deed from Frank and Christine Chichetto, the then-common owners of the two properties, to the Barneys' predecessors-in-title Francis and Grace Wiley, "reserving to the grantors [who retained the now-Jackson land] a right of way over driveway ten feet in width beginning at Adams Street and running parallel and adjacent to the southerly line of lot #1 on the above referred plan [the now Jackson property] approximately 148.34 feet [the full length of the common boundary line]." Deed, Chichetto to Wiley (Jun. 11, 1947), recorded in the Suffolk Registry of Deeds and explicitly referenced and incorporated into all succeeding deeds to the Barney land, including the Barneys'. See Deed, Dubard to Barney (Dec. 31, 2015).

[Note 3] See, e.g., "Atlas of the City of Boston, Dorchester, from Actual Surveys and Official Plans," Plate 34, Part of Wards 16 & 17, G.W. Bradley & Co. publishers, Philadelphia, PA (1933) (on file at the Land Court). The Jackson property is shown as being owned by Margaret Chapman at that time.

[Note 4] The tree was observed and the measurement taken at the view. The fact that the tree is many decades old was apparent from the height of the tree and the width of its trunk.

[Note 5] It is possible for the Barneys to create parking spaces outside of the easement in the area behind their house, but the Barneys, to date, have not done so. There is also on-street parking on nearby side streets, but this is less convenient than parking on-site, particularly when the Barneys are transporting their young children.

[Note 6] Memorandum and Order on Plaintiff's Motion for Preliminary Injunction at 5 (Jul. 30, 2018).

[Note 7] At the court's request, vehicle maneuvers took place and were observed at the view.

[Note 8] The back bumper of the car parked there at the time of the view was 16 ½ feet from the fence line.

[Note 9] This case is also referred to as The 107 Manor Avenue LLC v. Fontanella, et al. After the plaintiff, Robert Carlson's appeal, he transferred the property to The 107 Manor Avenue LLC. His motion to substitute a party was allowed.