Plaintiff Elizabeth Gillis Warden hopes to build a single-family dwelling on property located at 10 Harbor Way, in the Wings Neck neighborhood of Bourne ("Lot 19"). When the Town of Bourne Zoning Board of Appeals ("Board") upheld a denial by the Town of Bourne Building Inspector ("Building Inspector") of her building permit application in a decision dated and received by the Town Clerk on January 31, 2018 ("Decision"), she filed suit on February 16, 2018, pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17. Plaintiff now moves for summary judgment, contending that the Decision was arbitrary and capricious, exceeded the Board's power, and was made in error. Plaintiff asserts that her vacant lot is entitled to the grandfathering protections of G.L. c. 40A, § 6, and it was error for the Board to uphold the Building Inspector's determination that Lot 19 was not buildable due to it being in common ownership with and adjoining Lot 20. She further contends that a private street called Harbor Way runs between Lots 19 and 20 and precludes merger of those lots. Plaintiff seeks to annul the Decision.

On April 18, 2018, Plaintiff filed her Motion for Summary Judgment. The Board filed an opposition to Plaintiff's motion on September 17, 2018. Intervenors Newman Flanagan and Stanley Budryk, both Wings Neck neighbors, also filed an opposition on September 17, 2018.

Following a hearing on March 19, 2019, the parties were given an opportunity to supplement the record. Plaintiff filed Plaintiff's Post-Hearing Submission in Further Support of Her Motion for Summary Judgment on April 2, 2019, and on April 12, 2019, Defendants filed their Oppositon to Plaintiff's Supplementation of Summary Judgment Record and Additional Information, Documentation and Briefing. With the final submissions in hand, this matter was taken under advisement.

As discussed more fully below, I conclude that Lots 19 and 20 were not merged because Harbor Way, a private way, runs between the lots and is subject to the access rights of neighbors in the Wings Neck subdivision. On the record before the court, I cannot determine whether Plaintiff's property is entitled to grandfathering status, but as discussed below, the Board's Decision was based on erroneous application of the doctrines of merger and res judicata. Accordingly, I ALLOW Plaintiff's Motion for Summary judgment. This matter is remanded to the Board for further proceedings consistent with this memorandum and decision.

I. UNDISPUTED FACTS

Based on the pleadings and the documents submitted with the motion for summary judgment and oppositions, the following facts are undisputed or deemed admitted by the parties:

1. Plaintiff is the current title owner of 10 Harbor Way, or Lot 19 as labeled on Assessor's Map No. 45. Defs.' Resps. to Pls.' Concise Statement of Material Facts in Supp. of Her Mot. for Summ. J. ("Defs.' Resps."), ¶ 1; Pls.' App. of Ex. In Supp. of Her Mot. for Summ. J. ("Pls.' App.), Exs. B, C.

2. On April 28, 1948, the U.S. government conveyed a tract of land in Bourne to Plaintiff's grandfather, Frank Flanagan. This deed is recorded at the Barnstable County Registry of Deeds, Book 694, Page 58 ("Flanagan Deed").

3. Flanagan created Lot 19, as well as 13 additional house lots on Wings Neck from a portion of that land ("Flanagan Subdivision") by a subdivision plan entitled "Subdivision Plan of Land in Bourne (Pocasset) Mass., Subdivision of Lot A as shown on a plan by [Rutherford J. Kelley] dated June 2, 1949 and filed in the Barnstable Registry of Deeds, Plan Book 88, Page 3, Scale 1 in = 40ft., March 14, 1950, Ruthford J. Kelley., Reg. Land Sur., 223 Wren St., W. Roxbury, Mass.," dated March 14, 1950 ("Flanagan Subdivision Plan"). Pls.' App., Ex. E.

4. The Flanagan Subdivision Plan was approved by the Town of Bourne Planning Board ("Planning Board") on October 24, 1952 and recorded at the Barnstable Registry of Deeds on June 1, 1954, at Plan Book 115, Page 95.

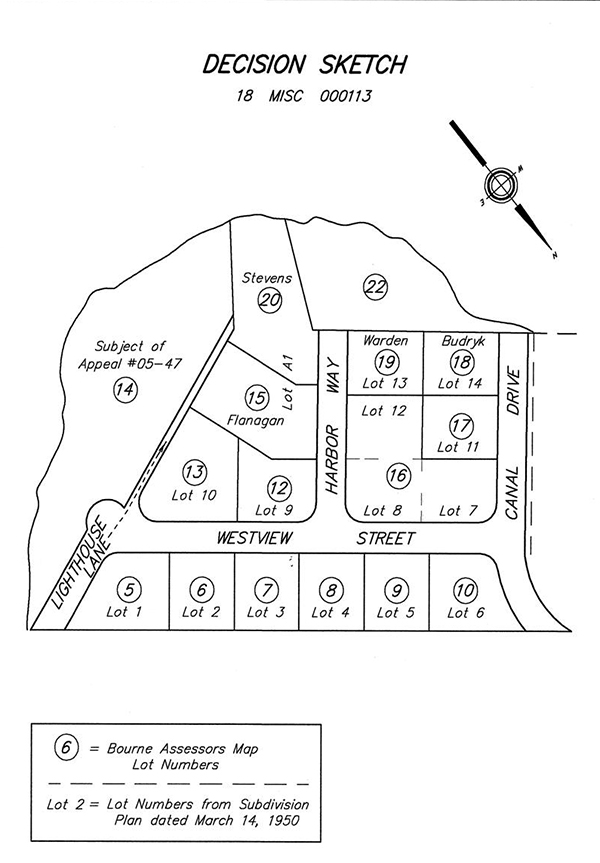

5. Three of the lots in the Flanagan Subdivision are of particular interest in this caseLot 19, as labeled on the Assessor's Map (also known as 10 Harbor Way), Lot 20 (Zero Lighthouse Lane), and Lot 14 (One Lighthouse Lane). On the Flanagan Subdivision Plan, Lot 19 appears as Lot 13, while Lot 20 appears as part of Lot A1 (which has since been subdivided), and Lot 14 is not identified. [Note 1]

6. Post subdivision, on September 21, 1983, Lots 14, 19, and 20 were conveyed by "Frank Flanagan, also known as Frank and Irene Flanagan" to their daughter (and Plaintiff's mother), Elizabeth Flanagan Gillis ("Elizabeth Sr."), by quitclaim deed recorded at Book 3895, Page 98. Defs.' Resps. No. 9; Pls.' App., Ex. F.

7. Thereafter, Lot 19 was the subject of a number of conveyances within and among the Flanagan family. Ultimately, on September 1, 2005, Plaintiff's sister, Christina Stevens, Trustee of the Lighthouse Realty Trust ("Stevens") conveyed Lot 19 to Plaintiff by quitclaim deed, recorded at Book 20251, Page 125. [Note 2] Pls.' App., Ex. B.

8. Lot 19 has an area of over 8,600 square feet and frontage of 82.52 feet on Harbor Way. Defs.' Resps. No. 8; Pls.' App., Ex. E. Lot 19 is listed by the Town of Bourne Assessor's Office as a buildable lot and has been taxed as such. Defendant's Responses, No. 14; Pls.' App., Ex. J.

9. When the Flanagan Subdivision Plan was approved and Lot 19 created, the Zoning By-Law for the Town of Bourne required that each dwelling house be erected on a lot in separate ownership from adjacent land and have a minimum of 6,500 square feet and a street frontage of at least 70 feet. Pl.'s Post-Hearing Subm. In Further Supp. of Her Mot. For Summ. J., Ex. BB. This zoning bylaw defined "lot" as an area of land with definitive boundaries and defined a "street" as a way open to public use or approved by the Planning Board. Id.

10. Harbor Way is a 40-foot wide private way that divides Lots 19 and 20, and is one of a number of private ways in the Flanagan Subdivision. Pls.' App., Ex. E.

11. Plaintiff applied to the Building Inspector for a permit to construct a single-family dwelling on Lot 19. The Building Inspector denied her permit application on August 14, 2017 on the basis that Harbor Way is not considered a "street" so as to separate Lots 19 and 20 ("Building Inspector's Decision").

12. In reaching its conclusion, the Building Inspector's Decision relied on a February 17, 2006 Board decision in another case involving the Flanagan Subdivision and Plaintiff's mother ("Appeal #05-47"). Defs.' Resps. No. 16, Ex. L. [Note 3]

13. Like the case at hand, the Board's 2006 decision in Appeal #05-47 also concerned parcels in the Flanagan Subdivision. Pls.' App., Ex. N. In Appeal #05-47, the Board considered whether Lot 14 in the Flanagan Subdivision was a buildable lot, and it ultimately agreed with the Building Inspector that Lot 14 was not buildable.

14. The Building Inspector's Decision explained the connection between Appeal #05-47 and the present case: "In the Zoning Board of Appeals decision in Case #05-47 (an Appeal of the Building Inspector's Decision), the Zoning Board ruled that Harbor Way is not considered a street. Therefore it does not 'separate' the two lots (Parcels 19 and 20)."

15. Plaintiff appealed the Building Inspector's Decision to the Board. On January 31, 2018, the Board filed with the Town Clerk its Decision upholding the Building Inspector's

Decision as to Lot 19. In its Decision, the Board adopted the Building Inspector's determination that Lot 19 is not buildable because it is contiguous with and in the same ownership as Lot 20. Plaintiff timely appealed the Decision to the Land Court.

16. Intervenors Newman Flanagan and Stanley Budryk own property in the Wings Neck neighborhood of Bourne within the Flanagan Subdivision, at Lots 15 and 18, respectively, on the Assessor's Map. These lots are depicted as Lot 18 and a portion of Lot 1A on the Flanagan Subdivision Plan.

II. DISCUSSION

A. Standard of Review

Summary judgment may be entered if the "pleadings, deposition, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Mass. R. Civ. P. 56 (c). See Regis College v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012). In viewing a summary judgment record, the court is to construe all facts "in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party . . . ." Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991).

Therefore, in evaluating a summary judgment motion, the court must consider two issues: (1) whether any factual disputes are genuine, and, if so, (2) whether those facts are material. Town of Norwood v. Adams-Russell Co., Inc., 401 Mass. 677 , 683 (1988), citing Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 247-248 (1986). To determine if a dispute about a material fact is genuine, the court must decide whether "the evidence is such that a reasonable [fact finder] could return a verdict for the nonmoving party." Anderson, supra, at 248. "As to materiality, the substantive law will identify which facts are material." Carey v. New England Organ Bank, 446 Mass. 270 , 278 (2006), citing Anderson, supra at 248; Molly A. v. Commissioner of the Dept. of Mental Retardation, 69 Mass. App. Ct. 267 , 268 n.5 (2007). "Only disputes over facts that might affect the outcome of the suit under the governing law properly preclude the entry of summary judgment." Anderson, supra, at 248.

When reviewing an appeal from a local zoning board decision, this court considers the facts de novo, but it must give some level of deference to the board's conclusion. Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003). The court is solely concerned with "the validity but not the wisdom of the board's actions." Wolfman v. Board of Appeals of Brookline, 15 Mass. App. Ct. 112 , 119 (1983). A court hearing an appeal under G. L.c. 40A, § 17 is not authorized to make administrative decisions. Pendergast v. Board of Appeals of Barnstable, 331 Mass. 555 , 557-558 (1954). If reasonable minds may differ on the conclusion to be drawn from the evidence, the board's judgment is controlling. ACW Realty Mgmt., Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Westfield, 40 Mass. App. Ct. 242 , 246 (1996). As such, a decision may not be overturned unless "it is based on a legally untenable ground . . . or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary." Id., quoting Subaru of New England. Inc. v. Board of Appeals of Canton, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 483 , 486 (1979) (omission in original, internal quotations omitted). Where the court's findings of fact support any rational basis for the municipal board's decision, the decision must stand. MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 638-639 (1970).

B. The Doctrine of Merger Does Not Preclude Lot 19 from Receiving the Benefits of Grandfathering

The central issue currently before this court is whether the doctrine of merger precludes Lot 19 from receiving the benefits of treatment as a preexisting, nonconforming lot. Under G. L. c. 40A, §6, preexisting nonconforming lots for single- and two-family residences are afforded certain protections. In relevant part, the statute provides:

Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply to a lot for single and two-family residential use which at the time of recording or endorsement, whichever occurs sooner was not held in common ownership with any adjoining land, conformed to then existing requirements and had less than the proposed requirement but at least five thousand square feet of area and fifty feet of frontage.

G. L. c. 40A, § 6 (emphasis added).

The emphasized language above indicates that not all preexisting, nonconforming single- and two-family lots benefit from these protections. To fall within the purview of G. L. c. 40A, § 6, a lot may not have been "held in common ownership with any adjoining land," meaning that it must not have merged with another lot. This so-called "merger doctrine" strives "to enable nonconforming lots to become conforming by combining the nonconforming lot with adjacent land, thus bringing the nonconforming lot into conformity." Pitsick, LLC v. Lipsitt, 23 LCR 277 , 287 (2015) (Misc. Case No. 13 MISC 477862) (Sands, J.). Undersized, adjoining lots that are held in common ownership will be treated as a single, merged lot for zoning purposes if doing so would eliminate or minimize the nonconformities. See Sorenti v. Board of Appeals of Wellesley, 345 Mass. 348 , 353 (1963) ("[A]n owner who has or has had adjacent land has it within his power, by adding such land to the substandard lot, to comply with the frontage requirement, or, at least, to make the frontage less substandard.").

The merger doctrine forms the basis for the Board's Decision, in which it agreed with the Building Inspector that Lot 19 merged with Lot 20 across Harbor Way. While Harbor Way may appear to separate Lots 19 and 20 on the Flanagan Subdivision Plan, the Board concluded the lots had merged by virtue of the derelict fee statute, G. L. c. 183, § 58. The derelict fee statute provides that owners of real estate abutting a waywhether public or privatehold the fee interest to the centerline of the way. Accordingly, the Board determined that Lots 19 and 20 merged at the centerline of Harbor Way, and Lot 19 could not satisfy the requirement that it was "not held in common ownership with any adjoining land." As a result, the Board found that the grandfathering protections in G. L. c. 40A, § 6 do not apply to Lot 19. [Note 4]

In her summary judgment motion, Plaintiff disagrees with the Board, arguing that Lot 19 is eligible for these protections because Lot 19 is not held in common ownership with any adjoining land. She contends that Lots 19 and 20 have not merged. To determine whether G. L.

c. 40A, § 6 applies to Lot 19, therefore, this court must first analyze whether Lots 19 and 20 have merged over Harbor Way.

In certain situations, Massachusetts courts have found that a physical barrier is sufficiently robust to prevent application of the doctrine of merger. See, e.g., Heavey v. Board of Appeals of Chatham, 58 Mass. App. Ct. 401 , 402 (2003) (no merger where body of water separated lots in common ownership). In Dowling v. Board of Health of Chilmark, 28 Mass. App. Ct. 547 , 548-549 (2003), the Massachusetts Appeals court explained that "a substantial physical barrier which, for practical purposes, prevents use of the two parts of the property as a unit" would prevent merger of two adjacent properties in common ownership. In Dowling, the physical barrier was a roadway that had been used by the public for over 32 years.

In Smith v. Town of Sutton Zoning Board of Appeals, Land Court Misc. Case No. 07 MISC 342017, slip op. at 11-14 (Feb. 3, 2010) (Trombley, J.), this court considered on summary judgment whether two lots in common ownership merged when they were separated by a paper street. The lots at issue had been conveyed only by reference to a plan and were construed to include the fee interest in the adjacent way, which was provided as the boundary for each lot.

The court explained:

Even though the derelict fee statute . . . allows deeds to be construed to so as to give landowners abutting a way the fee interest to the center line, in which case a landowner owning parcels on opposite sides of the paper street would own the fee in the entire way, that ownership is still subject to the rights of others to pass and repass over the way.

Id. at 10. Judge Trombley ultimately concluded that he could not determine who might have rights in the way on summary judgment where the original grantor made no express reservation of an easement over the way and the record did not include deeds for the other lots in the subdivision. It was unclear whether the subdivision lots included descriptions bounded by the way to create automatic easements by implication for the benefit of the other lot owners, which would create an actual physical impediment to use as a single lot. The court accordingly concluded that there were material facts in dispute to be determined at trial. Id. at 13-14.

This court also considered whether a paper street could prevent merger in Johnson v. Casper, 16 LCR 86 , 89-90 (2008) (Misc. Case No. 319146) (Sands, J.), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 1102 (2009). In that case, the court examined whether the paper street sufficiently interrupted the use of the property as one lot. Judge Sands explained: "The inquiry for purposes of determining grandfather status pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 6 . . . is not whether there are adjoining fee interests, but rather whether there are adjoining lots." Id. at 89. The test articulated in Johnson v. Casper is useful for the analysis at hand: whether the paper street sufficiently interrupted the use of the property as one lot. Id. In Johnson, the court ultimately concluded that the paper street prevented merger because it arose from recordation of a plan and, as such, could be used by any person with easements rights in the paper street.

Here, too, the record contains ample evidence that Harbor Way sufficiently interrupts the use of Lots 19 and 20 to prevent use of these lots as one. Unlike the court in Smith, the court in the present case has deeds for several lots in the Flanagan Subdivision. Plaintiff's Post-Hearing Submission included copies of deeds for Lots 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 12 and 14. Each of these deeds contains language providing the respective lot owners with rights over the streets, roads, and ways shown on the Flanagan Subdivision Plan, including Harbor Way. For example, the Lot 1 deed includes the following language with reference to the Flanagan Subdivision Plan:

There is also granted as appurtenant to the above described premises a right, in common with owners who are or may become entitled to similar rights, to use for all the purposes for which streets are used the streets and roads as shown on said plan and a right to pass and repass on foot over the passageways as show on said plan.

Barnstable County Registry of Deeds, Book 1070, Page 58. Similarly the deed for Lot 2, recorded at the Registry in Book 2431, Page 276, states: "The said premises are conveyed together with the right, in common with others now or hereafter entitled thereto, of access to the beach, and over the streets, roads and way shown on said plan." See also the deeds for Lots 4, 5, 7, 8, 12 and 14, recorded with the Registry at Book 28630, Page 79; Book 1170, Page 332; Book 12947, Page 015; Book 909, Page 241; Book 31609, Page 36; Book 1376, Page 1162; Book 1376, Page 1165; Book 11716, Page 348; Book 1108, Page 483; Book 19314, Page 225.

As such, the rights of other subdivision owners to use Harbor Way sufficiently interrupt the combined use of Lots 19 and 20 as a unified, merged lot. Indeed, an affidavit from just one Wings Neck neighbor submitted by the Intervenors explains that she has spent every summer on Wings Neck since 1963 and "I am very familiar with the appearance of Harbor Way at the location of the plaintiff's parcel 19 having walked there many times," presumably along the ways of the Flanagan Subdivision. Aff. of Julie C. Molloy, Sept. 13, 2018. As a result, the derelict fee statute does not cause Lots 19 and 20 to merge.

Further, cases considering the application of the derelict fee statute for zoning purposes make it clear that the derelict fee statute and the zoning laws serve separate and distinct purposes. In Sears v. Bldg. Inspector of Marshfield, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 913 , 913-914 (2009), the Appeals Court concluded that the derelict fee statute does not require a town to include the fee interests covered by that statute when calculating lot area required by its zoning bylaw or G. L. c. 40A, § 6. It explained that the derelict fee statute is "designed to deal with the enforcement of property rights and the problem of unowned lots," and it "has never applied, nor did the Legislature intend it to apply, to add lot area for zoning purposes." Id. at 914. See also Kubic v. Audette, 27 LCR 33 , 42 n.23 (2019) (Misc. Case No. 13 MISC 480929) (Cutler, J.) ("The fact that [a plaintiff] owns the fee in the southern half of the Right of Way does not make the Right of Way part of his lot."); Chopelas v. Kelly, 1 LCR 78 , 79 (1993) (Misc. Case No. 131369) (Cauchon, C.J.) ("The determinative factor as to whether the sideline or centerline of the abutting paper street should be used for zoning purposes is whether there are rights still existing in others to use the street as a private way.").

The Board also contends that Harbor Way has been eradicated between Lots 19 and 20, because that portion of Harbor Way lies near the terminus. As support for this contention, the Board cites to Emery v. Crowley, 371 Mass. 489 (1976). There, the Supreme Judicial Court held that lots must have frontage along the length of a way to have rights in the way. "[L]ogically, the lot owner at the end of a way cannot acquire any fee interest in the way without encroaching on the property rights, if any, of the abutting side owners." Id. at 494. See Diodati v. Kohl, 24 LCR 183 , 186 (2016) (Misc. Case No. 10 MISC 436806) (Speicher, J.) (finding that landowners at end of way did not have rights over it). Emery is inapposite in this case, however, because Lots 19 and 20 have frontage along Harbor Way, rather than lying at the terminus of the way, as was the case in Emery. At the terminus of Harbor Way is a parcel of land labeled "Lot 22" on the Assessors Map and as "U.S. Coast Guard" on the Flanagan Subdivision Plan. See Diodati v. Kohl, 10 MISC 436806 (2016). For these reasons, I conclude that Lots 19 and 20 have not merged, so as to preclude Lot 19 from the grandfathering protections of G. L. c. 40A, § 6.

Plaintiff also urges the court to apply the bylaws in existence at the time the Town approved the Flanagan Subdivision Plan in 1952 and find that Lot 19 is buildable. Plaintiff contends that Lot 19with a lot area of 8,662 square feet and frontage of 82.52 feet on Harbor Waymore than satisfies the minimum dimensional requirements of both the older bylaw and the dimensional minimums of G. L. c. 40A, § 6 (which requires 5,000 square feet and 50 feet of frontage). The record, however, is insufficient for the court to make this determination, particularly as to which bylaws apply to Plaintiff's proposed project.

C. Res Judicata Does Not Establish That Harbor Way is Not a Street

The Board contends that a 2005 Barnstable Superior Court case ("Barnstable Case") previously established that Harbor Way is not a street, and therefore, it cannot separate Lots 19 and 20. This court was not provided with a copy of the complaint in the Barnstable Case. [Note 5] However, that matter was an appeal of the Board's decision in Appeal #05-47, which is part of the summary judgment record. The Board argues that in approving the stipulation of dismissal in the Barnstable Action, the superior court affirmed the Board's decision in Appeal #05-47, such that Plaintiff is barred by res judicata from arguing that Harbor Way is a street.

The term res judicata encompasses both claim preclusion and issue preclusion. Kobrin v. Board of Registration of Medicine, 444 Mass. 837 , 843 (2005), citing Heacock v. Heacock, 402 Mass. 21 , 23 n.2 (1988). "Claim preclusion makes a valid, final judgment conclusive on the parties and their privies, and prevents litigation of all matters that were or could have been adjudicated in the action." Kobrin, supra, at 843, quoting O'Neill v. City Manager of Cambridge, 428 Mass. 257 , 259 (1998). To succeed on an assertion of claim preclusion, the Board must establish three elements: "(1) the identity or privity of the parties to the present and prior actions, (2) identity of the cause of action, and (3) prior final judgment on the merits." DaLuz v. Department of Correct., 434 Mass. 40 , 45 (2001), citing Franklin v. North Weymouth Coop. Bank, 283 Mass. 275 , 280 (1933).

Similarly, issue preclusion "prevents relitigation of an issue determined in an earlier action where the same issue arises in a later action, based on a different claim, between the same parties or their privies." Heacock, supra at 23, n.2. To succeed on the defense of issue preclusion, therefore, the Board must establish that: "(1) there was a final judgment on the merits in the prior adjudication; (2) the party against whom preclusion is asserted was a party (or in privity with a party) to the prior adjudication; and (3) the issue in the prior adjudication was identical to the issue in the current adjudication." Tuper v. North Adams Ambulance Serv., Inc., 428 Mass. 132 , 134 (1998). The third element requires that "the issue decided in the prior adjudication must have been essential to the earlier judgment." Id. at 134-135. See also Petrillo v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Cohasset, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 453 , 457 (2006); Cox v. Considine Dev. Co., LLC, 21 LCR 172 , 178 (2009) (Misc. Case No. 12 MISC 458355) (Sands, J.), quoting Kobrin, supra, at 843. Additionally, the issue must have been "actually litigated" in the prior case. Jarosz v. Palmer, 436 Mass. 526 , 531 (2002).

To test the validity of the res judicata claim, this court must look more carefully at Appeal #05-47 and the Stipulation of Dismissal in the Barnstable Case. In Appeal #05-47, the Board upheld the Building Inspector's determination that Lot 14which is not at issue in this casewas not a buildable lot. The Board found that Lots 14 and 20 were adjoining lots held in common ownership from 1959 to 2005, and thus, these lots had merged for zoning purposes. Appeal #05-47 did not determine the buildability of Lot 20 (which the Board contends has merged with Lot 19 in the present matter) or the buildability of Lot 19 itself. Instead, the Board's decision only concerned the buildability of Lot 14, which does not have frontage on Harbor Way. Nevertheless, in Appeal #05-47, the Board stated that "neither Lighthouse Lane [which runs between Lots 14 and 20 on the Flanagan Subdivision Plan] nor Harbor Way would be considered 'streets' under Bourne's Bylaws because neither road has at least 20 feet of paved 3 inch bituminous concrete in the areas abutting Parcel 20." This statement is the basis of the Board's res judicata argument.

Res judicata based on claim preclusion gives this court little pause because the Barnstable Case and the present matter involve different causes of action. The Barnstable Case concerned the buildability of Lot 14 and the present matter concerns the buildability of Lot 19. Issue preclusion, however, warrants further discussion. The identity of the parties is straightforward: The plaintiffs in the Barnstable Case were Plaintiff's parents, and the defendant was the Board. Defs.' App., Ex. Z. Not only does Plaintiff share a familial connection with the Barnstable Case plaintiffs, but Plaintiff is also their successor in title to Lot 19. As successor in interest to Elizabeth Sr. (who conveyed Lot 19 to Stevens, and Stevens, to Plaintiff), Plaintiff is in privity with the Barnstable Case plaintiffs for the purpose of determining if the Barnstable Case has preclusive effect on this case. See O'Donoghue v. Commonwealth, 93 Mass. App. Ct. 156 , 161- 162 (2018); Dombrowski v. Murphy, 26 LCR 218 , 220 (2018) (Misc. Case No. 17 MISC 000665) (Speicher, J.).

The remaining two issues are less clear, however. There is some case law to suggest that a stipulation of dismissal is not a "final judgment on the merits" for issue preclusion. See, e.g., Jarosz, supra, at 535-536; Department of Revenue v. Ryan, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 380 , 382-383 (20014). However, even if there were finality, there is no sufficient identity of the issues for preclusive effect in this case. As noted above, the issue must not only have been identical in both actions, but it also must have been actually litigated and essential to the judgment of the prior case.

Here, the lot at issue in the prior action (Lot 14) has frontage on Lighthouse Lane, not Harbor Way. Indeed, it does not even touch Harbor Way. That Lot 20 abuts Harbor Way (as well as Lighthouse Lane) could not logically have been "essential"or even relevantto either Appeal #05-47 or the subsequent Barnstable Case. Rather, the simple mention of Harbor Way in Appeal #05-47 was extraneous to the determination of merger in those cases. A conclusion that Lots 14 and 20 had merged was not grounded in the status of Harbor Way, but rather in their shared lengthy, contiguous boundary. As a result, there is no identity of the issues between the two actions. [Note 6] Plaintiff is not bound by the offhanded statement in Appeal #05-47 that Harbor Way is not a "street,"; neither Appeal #05-47 nor the Barnstable Case has a preclusive effect on the present matter.

III. CONCLUSION

For the reasons articulated above, Plaintiff's Motion for Summary Judgment is ALLOWED. Judgment shall enter annulling the Decision and remanding the matter to the Town of Bourne Zoning Board of Appeals for further proceedings consistent with this Decision.

ELIZABETH GILLIS WARDEN v. TOWN OF BOURNE ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, HAROLD A. KALICK, WADE M. KEENE, JOHN E. O'BRIEN, TIMOTHY M. SAWYER, AMY B. KULLAR, KATHLEEN BRENNAN, a/k/a KAT BRENNAN AND DEBRA BRYANT a/k/a DEBBIE BRYANT, as they constitute the Town of Bourne Zoning Board of Appeals. NEWMAN A. FLANAGAN and STANLEY BUDRYK, Defendant Intervenors.

ELIZABETH GILLIS WARDEN v. TOWN OF BOURNE ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS, HAROLD A. KALICK, WADE M. KEENE, JOHN E. O'BRIEN, TIMOTHY M. SAWYER, AMY B. KULLAR, KATHLEEN BRENNAN, a/k/a KAT BRENNAN AND DEBRA BRYANT a/k/a DEBBIE BRYANT, as they constitute the Town of Bourne Zoning Board of Appeals. NEWMAN A. FLANAGAN and STANLEY BUDRYK, Defendant Intervenors.