Mouhab and Laura Rizkallah live at 34 Arlington Street in Winchester and claim portions of their next-door neighbors' property at 30 Arlington Street by adverse possession or alternatively by prescription. The neighbors, Edward and Monica Driggers, after becoming aware of the Rizkallahs' claims, won the race to the courthouse and filed their quiet title and declaratory judgment action seeking to quiet their title as against the Rizkallahs' adverse claims. The Rizkallahs, by counterclaim, assert that they and their predecessors in title have established title by adverse possession, or have obtained an easement by prescription, to an area at the rear of the Driggers' property where both properties abut a golf course.

I denied the Driggers' motion for summary judgment on December 14, 2018. I took a view on November 1, 2019, and the case was tried before me over four days from January 14-17, 2020. Following the filing of post-trial briefs and requests for findings of fact and rulings of law, closing arguments were held before me and I took the matter under advisement on June 24, 2020.

Based on the findings of fact and rulings of law below, I find and rule that the Rizkallahs have failed to prove their counterclaims of adverse possession and easement by prescription, and that the Driggers are entitled to a judgment quieting their title to the disputed portions of their property and enjoining any trespasses on their property by the Rizkallahs.

FACTS

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence admitted at trial, my view of the subject properties, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, weight and inferences reasonably to be drawn from the evidence admitted at trial, I make factual findings as follows:

1. Dr. Mouhab Rizkallah purchased the property at 34 Arlington Street in Winchester on June 18, 2008. [Note 1]

2. The dwelling at 34 Arlington Street was built by a prior owner, James McKeown. [Note 2] McKeown and his wife Denise McKeown purchased the 34 Arlington Street property from Eugene R. Racek and Gretchen Racek on July 16, 1992. [Note 3]

3. McKeown died in November 1996, and his wife, Denise McKeown, sold the property to Garen and Jill Bohlin in December of 1997. [Note 4]

4. The Bohlins sold the property to Dr. Rizkallah in 2008. [Note 5]

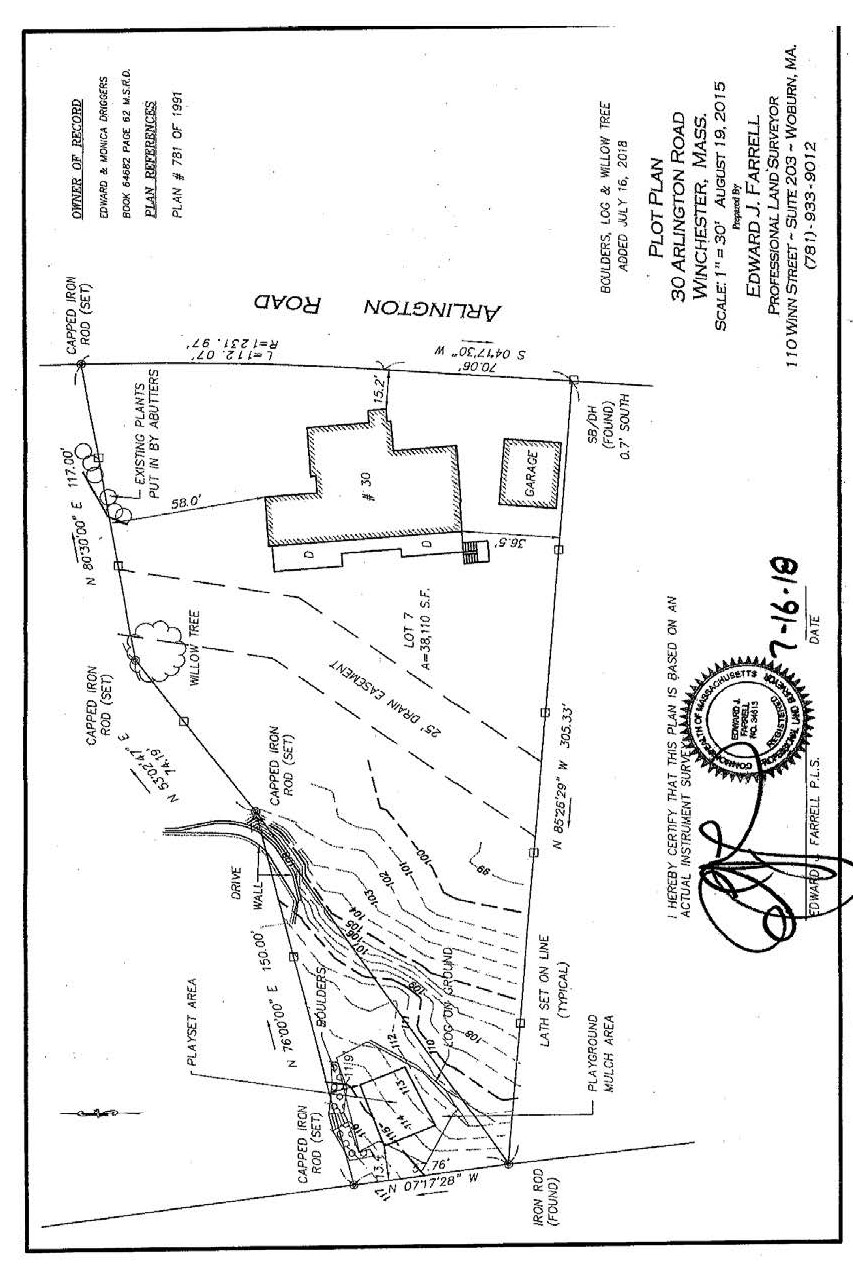

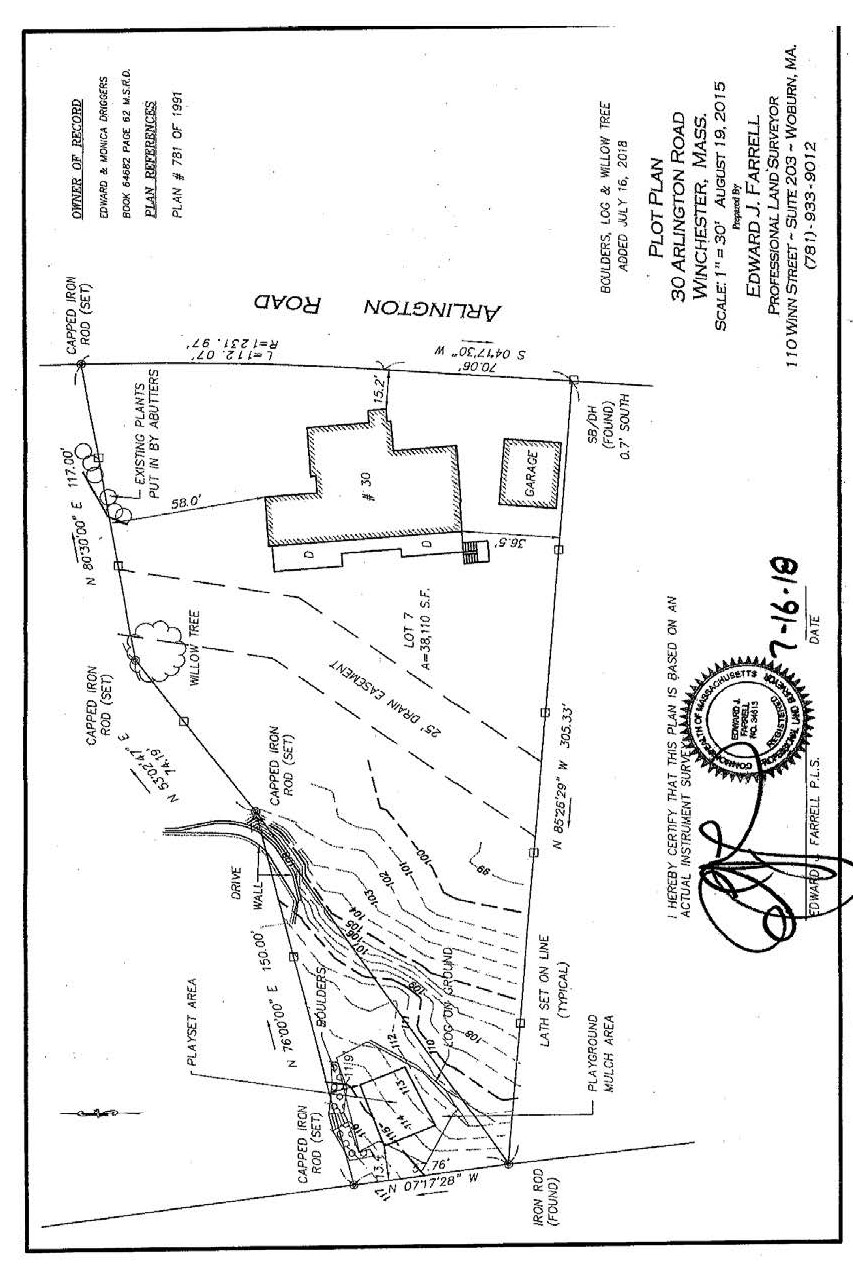

5. The Rizkallah property is roughly 45,000 square feet in area, and slopes first downward, then progressively upward from Arlington Street, with a long driveway and large front yard, with the house situated toward the rear of the property. [Note 6] There is a backyard behind the house, and the property abuts the Winchester Country Club golf course in the rear. [Note 7]

6. The plaintiffs Monica and Edward Driggers own and reside at 30 Arlington Street, next door to the Rizkallah property. [Note 8] They purchased 30 Arlington Street on December 16, 2014 from James and Kim Aiken. [Note 9] The Aikens had purchased 30 Arlington Street in 2005. [Note 10]

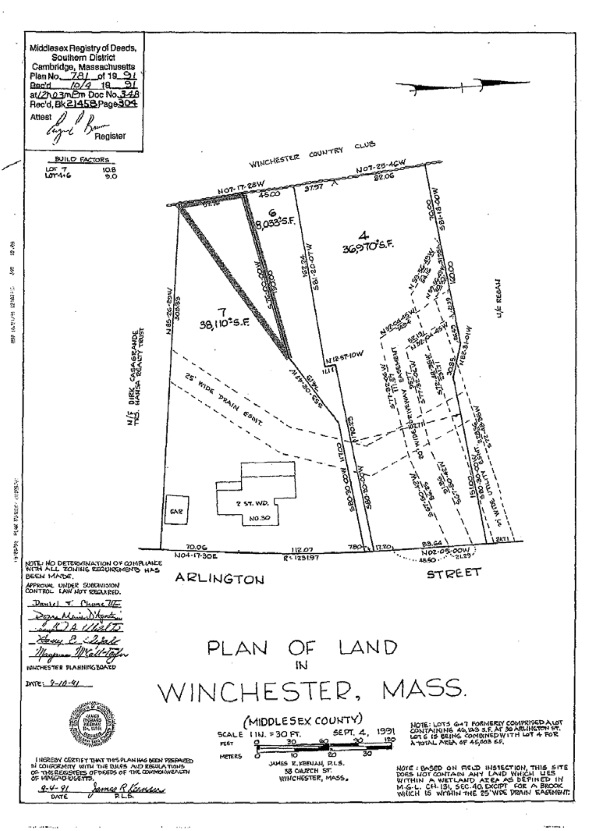

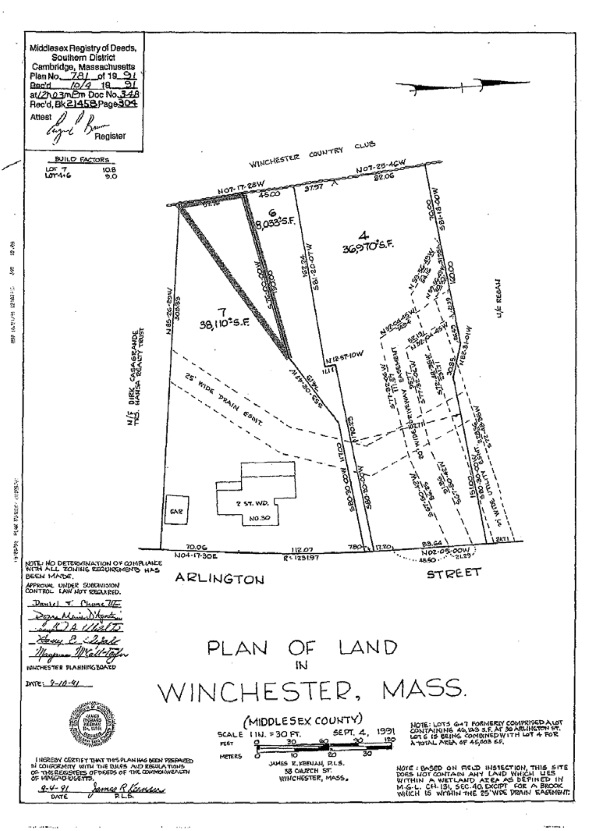

7. The Driggers property at 30 Arlington Street and the Rizkallah property at 34 Arlington Street were in common ownership until October 2, 1991, when Eugene R. Racek and Gretchen Racek sold 30 Arlington Street to Tamara Leaf and Thorkild Vad Norregaard, by a deed dated October 2, 1991, and recorded with the Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds on October 4, 1991 in Book 21458, Page 314. [Note 11]

8. The house on the Driggers property is sited at the front of the property close to Arlington Street, with a relatively flat backyard. [Note 12] At the back of the cleared portion of the backyard is a stream that crosses the property from north to south, with two bridges over it leading to the back part of the Driggers property. [Note 13] To the rear (west) of the stream, the backyard lawn continues until it meets a wooded embankment, which is left in a natural, mostly wooded state, and which slopes gently uphill toward the rear of the property, where it - like the Rizkallah property next door - abuts the Winchester Country Club golf course. [Note 14] The rear, westerly boundary of both the Driggers and Rizkallah properties is marked by a low stone wall. [Note 15] The Driggers property also slopes upward toward the Rizkallah property to the north. [Note 16]

9. At the rear, southwest corner of the Driggers property is an embankment. [Note 17] At the top of the embankment is a flat area, which is triangular in shape, and is bounded roughly by a log along the southern boundary of the area at the top of the embankment, on what would be the hypotenuse of the triangle. [Note 18] The area is also bounded by the low stone wall of the golf course boundary on the west, and the northwest portion of the third side of the triangle is defined by a low boulder wall, with steps leading up into the Rizkallah backyard. [Note 19] The low boulder wall and steps are on the record property of the Driggers. This low boulder wall is roughly parallel to, and just to the south of, the record property line between the Rizkallah and Driggers properties. [Note 20] At the "bottom" of this third side of the triangle, near the eastern end of the triangle along the north-south record boundary between the two properties, a stone-faced retaining wall supporting part of a paved basketball court on the Rizkallah property encroaches onto the record property of the Driggers. [Note 21] This triangular-shaped area is the disputed area over which the Rizkallahs seek to establish their counterclaim of adverse possession or easement by prescription. [Note 22]

10. Despite the hotly contested litigation of this case, there is actually little dispute as to the historical appearance and use of the disputed area, and I find those physical characteristics and uses to be as follows:

a. The dwelling at 34 Arlington Street, currently owned by Dr. Rizkallah, was built in 1993 by then-owner James McKeown, shortly after his purchase of the property from the common owner of both properties, the Raceks. [Note 23] A certificate of occupancy was issued in November, 1993. [Note 24] The house was constructed toward the rear of the property, with a long driveway leading up to the home from Arlington Street. [Note 25] No part of the driveway encroached on the property at 30 Arlington Street at this time. [Note 26]

b. Prior to 1994, and up until it was removed and replaced by Dr. Rizkallah in 2009, there was a retaining wall constructed of wooden railroad ties on the Driggers property, which served to level part of the backyard of the Driggers property, and to support part of the embankment on the northern side of the Driggers property. [Note 27] The railroad tie retaining wall ran roughly east to west on the Driggers property near its northern boundary with the Rizkallah property. [Note 28] There was no evidence presented at trial with respect to who built the railroad tie retaining wall. However, as there was no evidence to suggest that it was built by McKeown in conjunction with the construction of the house on 34 Arlington Street, it is likely, and I so find, that it was built prior to the separation of the two properties from common ownership by Eugene and Gretchen Racek, the common owners of the two properties, to facilitate a plan to subdivide their property. [Note 29]

c. I find that the railroad tie retaining wall was entirely on what it is now the Driggers property, and that it did not cross over or encroach onto what is now the Rizkallah property. Neither the landscaping plan nor the 1994 as-built plan for the house constructed on the Rizkallah property by McKeown depict any part of the railroad tie retaining wall encroaching on the Rizkallah property. [Note 30] I do not credit Dr. Rizkallah's testimony that neither of these plans could be expected to show the retaining wall. Both plans show features, including trees, and would be expected to show all built structures on the property. [Note 31] The as-built plan, in particular, shows the driveway on the Rizkallah property nowhere near the property line, and certainly not in a location that would have depended on the retaining wall for support. [Note 32] I specifically do not credit Dr. Rizkallah's testimony that the railroad tie retaining wall extended from the Driggers property over the boundary line in the same manner as does the present stone retaining wall. [Note 33] His assertion is not supported, and is in fact contradicted, by the evidence presented at trial, including the 1994 as-built plan. [Note 34]

d. Furthermore, I find that there was no credible evidence that the old railroad tie retaining wall was ever an encroachment from the now-Rizkallah property onto the now-Driggers property. As I have found, it was constructed by Eugene and Gretchen Racek or another common owner of the two properties before the properties were separated by the October 2, 1991 conveyance. Further, the railroad tie retaining wall was constructed entirely on the present Driggers property, with no physical encroachment onto the present Rizkallah property. The railroad tie retaining wall would have served the function of enlarging the level portion of the rear yard of the Driggers property, and may have been placed there by the Raceks to enlarge the level portion of the backyard of 30 Arlington Street, or to enlarge the useable area of 34 Arlington Street to facilitate its sale as a buildable lot after subdivision of the two lots, or both. There was no evidence to suggest otherwise, and the Rizkallahs failed to meet their burden of proving that the predecessor retaining wall was an adverse encroachment on the Driggers' property, regardless of whether it extended beyond the property line.

e. The evidence was also undisputed, and I so find, that the area between the railroad tie retaining wall and the boundary between the two properties remained unimproved and unused by any former owner of the Rizkallah property until Dr. Rizkallah dismantled the wall after he purchased the property in 2008.

f. In 1994, Ronald Nevola, a sprinkler and landscape lighting contractor working for McKeown installed an irrigation system and landscape lighting fixtures on the McKeown property. [Note 35] This included installation of three irrigation sprinkler heads south of the southerly property boundary of the McKeown property, in what is now the disputed area of the property owned by the Driggers. [Note 36] A pump, in a wooden pump box, was installed near the stream on the McKeown, now Rizkallah property. [Note 37] A high pressure water line was installed on the McKeown - now Rizkallah - property, running generally to the west toward the rear of the properties. [Note 38] At some point in what is now the triangular disputed area, the high pressure line crossed over to the Driggers property, where it was connected to a wooden-lidded valve distribution box buried in the ground, with its cover above ground. [Note 39] From there, underground lines led to the three sprinkler heads that were installed in the ground in the disputed area: one near a log roughly along the southern boundary of what is now the disputed area; one near the eastern corner of the disputed area; and one near the northwest corner of the disputed area, by the golf course wall. [Note 40] The sprinkler heads, about two and a half inches in diameter, were flush to the ground except when activated about three times a day during the warmer months. [Note 41]

g. Mr. Nevola testified that he maintained the irrigation system from 1994 to 2002, and again between 2006 and 2008, and that he activated the system each spring and drained and shut it down each fall during those years. [Note 42] He did not testify as to the time of day the sprinkler heads were set to operate. I credit his testimony that the sprinkler heads, including those in the disputed area, were installed and operating during these two periods.

h. The pump for the irrigation system failed in 2002, and was not replaced until 2006, and so the sprinkler heads in the disputed area, along with the rest of the irrigation system, were not in operation from 2002 until the pump was replaced in 2006. [Note 43] Mr. Nevola did not return to the 34 Arlington Street property during this period.

i. Also installed in 1994 in the disputed area were three landscaping "uplights" designed to illuminate trees and overhanging branches. [Note 44] These were almost flush to the ground, but protruded perhaps an inch and a half from the ground so as not to be buried by mulch or leaves. [Note 45] They were intended to be activated each night. [Note 46] Other such lights were installed through the rest of the then-McKeown backyard, adjacent to the disputed area.

j. The installer, Mr. Nevola, also testified that the landscape lighting, which was powered by low-wattage incandescent bulbs of 25-30 watts, was set to go on each evening when it got dark and to turn off in the morning, by a control system combination of photo-sensors and timers. [Note 47] He testified that these three lights and the lights in the adjacent McKeown backyard were pointed straight up so as to illuminate tree trunks and overhanging branches in their immediate vicinity. [Note 48] I credit this testimony.

k. Mr. Nevola also testified that these lights operated from 1994 to 2009. [Note 49] He did not, however, return to the property to maintain the irrigation or lighting systems from 2002 to 2006. [Note 50] He further testified that during the years he was not maintaining the irrigation system or lights, he would drive by on Arlington Street and would see the lights operating. [Note 51] I do not credit this testimony, as I find it less than credible that one driving by on Arlington Street, down an incline and a few hundred feet away from the disputed area, in a few moments while passing between the two houses, would be able to determine that specific lights up the hill in the woods behind both houses on the subject properties were operating on any particular side of the property line. [Note 52]

l. Prior to the purchase of 34 Arlington Street by Dr. Rizkallah, the disputed area was down a slight slope from the lawn of the McKeown backyard, and was characterized by an open area in which large, relatively flat, granite stones with an unfinished, rough surface were embedded into the ground. [Note 53] All witnesses with personal knowledge of the appearance of these stones for the period from 1994 to 2009 testified, and I so credit their testimony, that the stones were generally greenish in color, as they were covered with moss. [Note 54] There was also grass between the stones. [Note 55] At some point, there was a mulch pile that accumulated in the rear, northwest corner of the disputed area, near the low stone golf course wall. [Note 56]

m. With the exception of the presence of the landscaping "uplights," valve distribution box, and the sprinkler heads, there was no testimony of any active use, or in fact any use at all, of the disputed area at any time between 1994 and 2009. [Note 57] There was no backyard furniture or structures of any kind placed in the disputed area by Dr. Rizkallah's predecessors in title, nor was there any testimony to support a finding of any kind of active use of the disputed area during the period before Dr. Rizkallah's ownership. [Note 58] There was testimony that there was grass between the flat stones in the disputed area, but I do not find, based on this testimony, that there was any regular maintenance of this area. [Note 59] The area is largely shaded and was taken up mostly by large, flat stones covered with moss, (indicating a lack of regular maintenance) and there was no suggestion that grass would grow well enough in such an area to require any regular mowing or other maintenance. Furthermore, testimony that the area was "maintained" was not based on personal observations of maintenance (e.g., mowing, weeding) in the disputed area, and to that extent I do not credit such testimony.

n. A hotly disputed issue in this case is the origin of a log that lies today on the southern boundary of the disputed area, roughly along part of the hypotenuse of the triangle-shaped disputed area. [Note 60] I find, based on all the evidence, that this log was in existence in 1994 in the same location as it is today, but that prior to 2009 it was partially covered by soil, leaves and other natural debris. [Note 61] There was no evidence that the log was placed in that location by any present or prior owner of either of the subject properties, and I find that the log is simply a fallen tree, with its larger branches still intact today. [Note 62] I find that while the log became a convenient and obvious boundary of the disputed area, it was not placed there on purpose by any present or prior owner; it simply fell and happens to be lying along the top of an embankment. A log intended to be used as a monument for a property boundary would likely have been trimmed of its branches, and would also likely not have been left more than half-buried for at least fifteen years, as this log was.

o. There was testimony that down the embankment from the log, in the woods on the Driggers property, piles of leaves and yard waste have been observed. [Note 63] There was further testimony that while working for Dr. Rizkallah in 2009, a landscape worker dumped leaves from the Rizkallah property over onto the embankment sloping down toward the Driggers' back yard. [Note 64] There was, however, no direct testimony that anyone working on the Rizkallah property prior to Dr. Rizkallah's ownership actually crossed the disputed area and dumped leaves over the embankment onto the Driggers property. [Note 65] The leaves seen in that area prior to the Rizkallah's ownership of 34 Arlington could as easily - and likely - have been placed in the woods behind the Driggers house by the Driggers' predecessors. I do not credit the suggestion in testimony on behalf of the Rizkallahs that leaves dumped at the bottom of the embankment came from what is now the Rizkallah property.

p. After Dr. Rizkallah purchased 34 Arlington Street in 2008, [Note 66] he made physical changes to the disputed area and he began active use of the disputed area. He replaced the railroad tie retaining wall - which was entirely on the Driggers property - with a larger, stone masonry retaining wall, which crossed over the property line from the Rizkallah property onto the Driggers property at the corner of the disputed triangle nearest the Rizkallah house. [Note 67] While the old railroad tie retaining wall did not support any driveway or other paved surface encroaching from the Rizkallah property onto the Driggers property, the new retaining wall supported a new encroachment beside the wall: a paved basketball court. [Note 68] These improvements were constructed within 100 feet of a stream and therefore were constructed apparently illegally, since they were constructed without the benefit of an order of conditions from the Winchester Conservation Commission. [Note 69] They were built in 2009 or 2010.

q. Dr. Rizkallah completely reworked the area near the back of the disputed triangle in the vicinity of the golf course wall and the log. In 2009, he had the landscaping lights and the sprinkler heads removed. [Note 70] New sprinkler heads were installed in the disputed area. [Note 71] In 2009, the large, flat stones were removed and relocated so that they formed a walkway along the record boundary line leading to the back of the Rizkallah house. [Note 72] The stones were cleaned of the moss that had covered them by power washing. [Note 73] The area was regraded to make it level, and a bed of mulch suitable for a play area was placed on the now-level ground. [Note 74] What had been a gentle grade to the backyard proper of the Rizkallah property was improved by the construction of a low stone retaining wall and steps from the backyard, which was on the Rizkallah property, down into the new play area in the disputed area. [Note 75] The new wall and steps encroached from the record Rizkallah property onto the disputed area. [Note 76] In the summer of 2010, Dr. Rizkallah installed an elaborate swing and play set for his children to use on the new level mulched area. [Note 77] The entirety of the swing set is over the record boundary line onto the Driggers property. [Note 78]

r. Since 2008 or 2009, Dr. Rizkallah and his family have used the play area on the disputed area on a regular basis. [Note 79]

11. The Aikens were the Rizkallahs' neighbors at 30 Arlington Street from the time the Rizkallahs purchased the property in 2008 until late 2014. [Note 80] They had a friendly neighborhood relationship during that period. [Note 81] In addition, Dr. Rizkallah had a business relationship with Mr. Aikens, who was an insurance broker. [Note 82] Mr. Aiken provided (and continues to provide) insurance for some of the residential apartments Mr. Rizkallah owns. [Note 83]

12. On at least two occasions, Dr. Rizkallah and Mr. Aiken had discussions about Dr. Rizkallah's desire to purchase part of the rear of the property from the Aikens. [Note 84] Additionally, Dr. Rizkallah emailed Mr. Aiken, expressing his interest in buying part of the rear of the property if the Aikens intended to sell their lot. [Note 85] These discussions never came to anything.

13. Around April of 2010, another neighbor, Dirk Casagrande, approached Dr. Rizkallah in the vicinity of the disputed area and informed Dr. Rizkallah that he believed Dr. Rizkallah's play area was encroaching on the Driggers' (then the Aikens') property. [Note 86] Following this discussion, Dr. Rizkallah approached Mr. Aiken and told Mr. Aiken that he believed the swing set encroached on the Aikens' property by a small amount, perhaps a few feet. [Note 87] At that time, Mr. Aiken believed the encroachment to be only a few feet. [Note 88] Mr. Aiken told Dr. Rizkallah that he was not concerned about the encroachment and did not intend to insist that Dr. Rizkallah move the swing set. [Note 89]

14. The Driggers purchased 30 Arlington Street from the Aikens on December 16, 2014. [Note 90] For about the first year they had friendly relations with the Rizkallahs. [Note 91] In December 2015, the Driggers had the first of a number of surveys of their property prepared, and confirmed that Dr. Rizkallah's play area was almost entirely on their property. [Note 92] Mr. Driggers and Dr. Rizkallah had a conversation in December, 2015, in which Dr. Rizkallah informed Mr. Driggers that he considered the area to be his, and that he would not move the play area and its improvements. [Note 93] This litigation followed.

DISCUSSION

"Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive, and adverse for twenty years." Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). The "necessary elements of such possession [include] the obligation to show that it was actual, open, continuous, and under a claim of right or title." Mendonca v. Cities Service Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968). The burden of proving each element falls upon the party claiming title by adverse possession. Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003). "The acts of the wrongdoer are to be construed strictly and 'the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof.'" Tinker v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74 , 76 (1912), quoting Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 (1853). "If any of the elements remains unproven or left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail." Sea Pines Condominium III Ass'n v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 847 (2004).

"An adverse possession claim requires that possession be 'actual' in nature, meaning that the possessor must be actually utilizing the land that he or she is claiming." Chew v. Kwiatkowski, 19 LCR 88 , 91 (Mass. Land Ct. 2011) (Trombly, J.). To prove actual use, the plaintiff "must establish changes upon the land that constitute 'such control and dominion over the premises as

to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership.'" Id.

In looking to the extent of the claimant's acts upon the land, this showing of dominion and control is closely linked to the requirement that the use be likewise open and notorious. An open use is one undertaken without attempted concealment; to be notorious, "it must be sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property." Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007). "The purpose of the requirement of 'open and notorious' use is to place the true owner 'on notice of the hostile activity of the possession so that he, the owner, may have an opportunity to take steps to vindicate his rights by legal action.'" Lawrence v. Town of Concord, supra, 439 Mass. at 421, quoting Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333-334 (1959). "The nature of the occupancy and use must be such as to place the lawful owner on notice that another person is in occupancy of the land, under an apparent claim of right[.]" Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, supra, 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 848. Acts under a claim of right are those undertaken "with an intention to appropriate and hold the same as owner, and to the exclusion, rightfully or wrongfully, of everyone else." Lawrence v. Town of Concord, supra, 439 Mass. at 421 n.5, quoting Bond v. O'Gara, 177 Mass. 139 , 144 (1900). [Note 94]

The particular acts that would be consistent with ownership, as well as those sufficient to provide notice to the true owner, will vary depending on the features of the land in question, and the court must therefore consider the conjunction of "the nature of the occupancy in relation to the character of the land." Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 623-624 (1992). "Evidence insufficient to establish exclusive possession of a tract of vacant land in the country might be adequate proof of such possession of a lot in the center of a large city." LaChance v. First Nat'l Bank & Trust Co., 301 Mass. 488 , 490 (1938). "Acts of possession which are 'few, intermittent and equivocal' do not constitute adverse possession." Kendall v. Selvaggio, supra, 413 Mass. at 624, quoting Parker v. Parker, 83 Mass. 245 , 247 (1861). "[T]he determination whether a set of activities is sufficient to support a claim of adverse possession is inherently fact-specific." Sea Pines Condominium III Ass'n v. Steffens, supra, 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 848.

Given the character of the disputed area, including its location at the top of a slope on an undeveloped part of the property at 30 Arlington Street, in an area that generally was left in its natural wooded condition, the type of activity that would support a claim of adverse possession would be further along the scale of the type of proof required for wooded, undeveloped land, than for developed, urban land. See Kendall v. Selvaggio, supra, 413 Mass. at 624.

The Rizkallahs also seek, as an alternative remedy, to establish an easement by prescription over the disputed area, which they mistakenly label in their counterclaim an "exclusive-use easement . . . by prescription." "Acquiring an easement by prescription requires 'clear proof of a use of the land in a manner that has been (a) open, (b) notorious, (c) adverse to the owner, and (d) continuous or uninterrupted over a period of no less than twenty years.'" Barnett v. Myerow, 95 Mass. App. Ct. 730 , 738 (2019), quoting Smaland Beach Ass'n v. Genova, 94 Mass. App. Ct. 106 , 114 (2018). Essentially, the elements for proof of an easement by prescription are the same as for a claim of adverse possession, minus the requirement of exclusivity. The Rizkallahs have mischaracterized their alternative counterclaim as one for an "exclusive" easement by prescription, as an easement by prescription is, by definition, not an exclusive easement.

I. THE RIZKALLAHS HAVE FAILED TO CARRY THEIR BURDEN OF ESTABLISHING TITLE BY ADVERSE POSSESSION OR BY PRESCRIPTION TO THE PLAY AREA.

The dispute that sparked the present litigation centers on the play area near the rear of the disputed area, which includes the flat, mulched area improved by an elaborate children's play set, and which also includes the low stone wall and stone steps constructed by Dr. Rizkallah after re-grading the area in 2009. The Rizkallahs have demonstrated that, commencing in 2009, their activities in this area have been actual, open and notorious, continuous and adverse. However, they have failed to meet their burden of proving that they have met the requirements for a claim of adverse possession (or for a prescriptive easement) continuously for the requisite twenty years.

The physical appearance of the part of the disputed area, prior to 2009, that Dr. Rizkallah later converted into a play area, does not credibly support a finding that there were any improvements to the disputed area that would put any reasonable owner of the Driggers property on notice of an adverse claim.

There was no evidence at trial to suggest who installed the flat granite stones in the disputed area, or whether those stones had been installed by a prior owner at all. But even assuming they had been placed there by a prior owner of the Rizkallah property, their appearance was not sufficient to give rise to any finding that they constituted an adverse encroachment onto what is now the Driggers property.

The undisputed testimony in regard to the appearance of the granite stones' appearance from 1994 to 2009 was that they were green and moss-covered, which suggests that no one was cleaning, maintaining or otherwise using the stones to support any use of the disputed area. They do not have finished, milled or ground flat surfaces; rather, their surfaces are rough and only approximately flat. Accordingly, the presence of these relatively flat, moss-covered granite stones would not put an owner on notice of any actual possession of this area by Dr. Rizkallah's predecessors in title.

The fact that there was grass between the stones does not change this conclusion. There was no testimony as to any care or mowing of this grass in this area on any regular basis, and the mere presence of grass between a series of relatively flat stones does not indicate that an adverse possessor has installed or is caring for the grass. In particular, there was no evidence at trial of the condition of the grass or of any regular maintenance of the grass in this area during the period spanning 1994 to 2009. Even in situations, unlike this one, where there had been routine lawn maintenance, this court has often found that, without significant improvements or alterations, routine lawn maintenance, with little or nothing more, does not serve to sufficiently exert dominion and control or place the true owner on notice of an adverse claim. See, e.g., Doucette v. Nix, 23 LCR 657 , 663 (Mass. Land Ct. 2015) (Piper, J.); Beene v. Silva, 23 LCR 189 , 192 (Mass. Land Ct. 2015) (Long, J.); Berman v. Johnson, 16 LCR 644 , 649 (Mass. Land Ct. 2008) (Long, J.); Frigoletto v. Pirro, 15 LCR 161 , 165 (Mass. Land Ct. 2007) (Long, J.); Arnold v. Lamanna, 15 LCR 300 , 303 (Mass. Land Ct. 2007) (Sands, J.), aff'd 72 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (July 15, 2008) (Rule 1:28 Decision); Cyr v. Burke, 13 LCR 456 , 461 (Mass. Land Ct. 2005) (Lombardi, J.); Courville v. Kohn, 12 LCR 455 , 458 (Mass. Land Ct. 2004) (Lombardi, J.); Ciccone v. Ciccone, 1 LCR 176 , 178 (Mass. Land Ct. 1993) (Cauchon, J.).

The only evidence of actual physical improvements by a prior owner of the Rizkallah property in this part of the disputed area was the presence of a valve distribution box for the irrigation system - mostly buried but with its wooden cover showing - three sprinkler heads, and three landscape lights. The sprinkler heads and the lights were buried so as to be flush or nearly flush with the ground. The presence of the valve box - and, when not operating, the sprinkler heads and lights, flush or nearly flush to the ground - in an area in the woods, with a surface often covered with leaves and mulch, is insufficient to constitute a presence that is either "open" or "notorious." Even a diligent landowner walking through the disputed area is likely not to have seen these features, flush or nearly flush with the ground amidst leaves and mulch. These features were not "such as to place the lawful owner on notice that another person is in occupancy of the land, under an apparent claim of right[.]" Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v. Steffens, supra, 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 848.

Nor was the evidence of the operation of the lights and the sprinkler heads sufficient to put an owner on notice of an adverse claim. The area in which the lights and the sprinkler heads

were located was up a slope and well into the wooded area behind the house on the Driggers' property. The periodic operation of sprinkler heads, even on a daily basis, back in the woods and up a slope from the occupied part of the property, in an area not regularly traversed, would not put a reasonable owner on notice of an effort to exercise dominion over the property. The operation, even on a nightly basis, of the landscaping lights would similarly not provide such notice. These lights were only three of many other lights operating at the same time in the adjacent McKeown/Bohlin/Rizkallah backyard. Given the distance from the house on the Driggers property, the slope, the intervening woods, and the adjacency of the three encroaching lights to the other lights in the McKeown/Bohlin/Rizkallah backyard, it would not be apparent to any reasonably observant owner of the Driggers property that those three lights were installed over the property line.

Even were the operation of the lights and the sprinkler heads sufficient to put an owner of the Driggers property on notice of an encroachment, this activity was not continuous for a sufficient time, as it was interrupted between 2002 and 2006. The only testimony regarding the installation and operation of the lights and sprinklers was by installer Ronald Nevola, who was not employed to maintain or operate either the irrigation system or the landscape lighting and was not present at the property between 2002 and 2006. It is undisputed that the irrigation system was not operating between 2002 and 2006. As for the lights, Mr. Nevola testified only that he saw the lights operating during this period when he drove by on Arlington Street at night, but I do not credit this testimony, as I find it unlikely that even one intimately familiar with both properties would be able to discern, while momentarily driving by hundreds of feet away, looking to the side, between the two houses, up a slope and through a wooded area, whether three low-wattage lights in the distance were on one side of the property line or the other - if they could be seen at all. There was no other evidence presented regarding the operation of the lights during this period. Thus, credible proof is lacking of any qualifying adverse use that the operation of the lights and the sprinklers might have entailed for at least a period of four years during the claimed period of adverse use and possession from 1994 through the commencement of the present action.

The Rizkallahs point to evidence that their predecessors' landscapers crossed the disputed area to dump leaves and other gardening debris over the embankment into the woods behind the Driggers house. However, there was no direct evidence presented that anyone working on the Rizkallah property prior to the Rizkallahs' ownership ever crossed the boundary line to dump leaves on the now-Driggers property. Rather, leaves were merely observed in the embankment area on the Driggers property - but without evidence otherwise, it cannot be concluded that the then-owner of the Rizkallah property was the party who did the leaf dumping.

Even assuming that the then-owner of the Rizkallah property was responsible for the leaf dumping over the boundary line onto the Driggers property, this limited and intermittent activity cannot be characterized as an action unequivocally associated with a claim of ownership; it is, in fact, more consistent with an adjacent landowner's attempt to place unwanted debris beyond the bounds of his own property, and thus is not unambiguous treatment of that area as his own. Such leaf dumping is pointedly dissimilar to the significant acts of improvement, cultivation, or alteration that are the characteristic uses attendant to ownership. Cf. Peck v. Bigelow, supra, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556. Furthermore, standing alone, it is the type of "intermittent and equivocal" use of the property that cannot serve to establish actual adverse use of this area. See Kendall v. Selvaggio, supra, 413 Mass. at 624.

Moreover, given the wooded and unimproved character of this part of the Driggers property, this use, if proven by evidence at trial, would fail to qualify as open and notorious. "In the circumstances of wild and unimproved land, a more pronounced occupation is needed" to place the lawful owner on notice of an apparent claim of right. Sea Pines Condo. III Ass'n v.

Steffens, supra, 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 848.

Finally, there was no evidence at trial, credible or otherwise, of any actual use of the disputed area until Dr. Rizkallah made changes to the disputed area, turning it into a play area in 2009. There was no testimony of any use at all of the disputed area by the McKeowns or the Bohlins, the two predecessor-owners of the Rizkallah property. No lawn furniture, no toys, and no structures of any kind were placed in the disputed area, and I have found that the log marking what has become part of the southern boundary of the disputed area was simply a fallen tree in the woods. There was no testimony, credible or otherwise, that any member of the McKeown family or the Bohlin family ever even walked across the disputed area, let alone made any adverse use of it. The occasional entry of the persons maintaining the irrigation system and the landscape lighting, as well as the potential occasional entry of a landscaper to dump leaves over the embankment, as I have found, was intermittent at best.

Accordingly, the Rizkallahs have failed to carry their burden on their adverse possession and prescriptive easement claims with respect to the play area and stone wall and steps in the disputed area.

II. THE RIZKALLAHS HAVE FAILED TO CARRY THEIR BURDEN OF ESTABLISHING TITLE BY ADVERSE POSSESSION OR BY PRESCRIPTION TO THE RETAINING WALL AND BASKETBALL COURT ENCROACHMENT.

After Dr. Rizkallah purchased 34 Arlington Street, he razed an existing railroad tie retaining wall that was located entirely on the property next door at 30 Arlington Street - apparently without any permission from the Aikens, who then owned the property at 30 Arlington Street - and replaced it with a stone and masonry retaining wall that is partly on his property and partly encroaches on the Driggers property at 30 Arlington Street. Additionally, he razed the existing wall and constructed the new one also without seeking or obtaining a necessary order of conditions from the Winchester Conservation Commission, even though the work was within 100 feet of the stream that traverses both properties.

As I have found, the former railroad tie retaining wall was entirely on what is now the Driggers property at 30 Arlington Street, and it potentially served two functions: it could have supported part of the property at 34 Arlington Street, and it could have created additional level area in the side yard of the property at 30 Arlington Street. There was no evidence as to whether the wall's intended purpose was one or both of these functions.

The evidence suggests, and I have found, that the railroad tie retaining wall was constructed by the common owner of the two properties before they were separated by a conveyance in October, 1991. Accordingly, there was thus no evidence to support a finding that the railroad tie retaining wall constituted an adverse encroachment onto the 30 Arlington Street property by any prior owner of the 34 Arlington Street property. This would be true even if the railroad tie retaining wall physically encroached onto the property that was later subdivided to become 34 Arlington Street, which it did not.

There also was also no evidence that the area between the top of the railroad tie retaining wall and the boundary between the Rizkallah and Driggers properties was paved, landscaped, or improved by any structures or used in any way by the prior owners of the Rizkallah property. Hence, the earliest evidence of adverse possession by encroachment of a retaining wall or other structure onto the Driggers property is the construction of the new retaining wall and the paved basketball court it supports, by Dr. Rizkallah, no earlier than 2009. This, of course, falls far short of the twenty years necessary to prove a claim of adverse possession. Accordingly, although the adverse incursion of the stone and masonry wall onto the Driggers property is actual, open and notorious, exclusive and continuous, it has not been so for the requisite twenty-year period, and so the Rizkallahs' adverse possession claim, as well as their prescriptive easement claim, for this remaining part of the disputed area fails.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, the Rizkallahs' counterclaims for adverse possession and for establishment of a prescriptive easement fail. The Driggers will be awarded an appropriate judgment declaring that they have good and clear marketable title to their record property free and clear of any claims by the Rizkallahs.

ADDENDUM A

ADDENDUM B

EDWARD DRIGGERS and MONICA DRIGGERS vs. MOUHAB RIZKALLAH and LAURA RIZKALLAH

EDWARD DRIGGERS and MONICA DRIGGERS vs. MOUHAB RIZKALLAH and LAURA RIZKALLAH