ADRIAN BIGNAMI and PETRA BIGNAMI v. MIGUEL SERRANO and MARISA SERRANO

ADRIAN BIGNAMI and PETRA BIGNAMI v. MIGUEL SERRANO and MARISA SERRANO

MISC 18-000323

May 7, 2020

Norfolk, ss.

LONG, J.

ADRIAN BIGNAMI and PETRA BIGNAMI v. MIGUEL SERRANO and MARISA SERRANO

ADRIAN BIGNAMI and PETRA BIGNAMI v. MIGUEL SERRANO and MARISA SERRANO

LONG, J.

Introduction

This case concerns a driveway on plaintiffs Adrian and Petra Bignami's land on Tappan Street in Brookline. By express easement, that driveway is shared with the property behind them, owned by defendants Miguel and Marisa Serrano, and is the sole access to both those homes.

Shared driveways are always uneasy arrangements, but its issues in this instance are intensified by the driveway's location (close to the side of the Bignamis' house), its narrowness (one car wide, with no room for vehicles to pass each other or pull over when a car comes from the opposite direction), and the need, most particularly for the safety of the Bignamis' young children, to ensure that vehicles drive slowly over it.

And these are not the only disputes between the parties. Relations between them are so bitter that the Bignamis have installed video surveillance cameras covering the entirety of the shared driveway to record the Serranos' use of it, a surveillance which inevitably records not only the adult Serranos and their visitors, but also the Serranos' young children and the Serranos' interactions with them. In addition, the Bignamis claim the right to drive onto the Serranos' land and to park in any garage the Serranos may build.

The context from which their disputes arose is as follows.

The Bignamis' property, which fronts on Tappan Street, is #146 (hereafter "#146" or "the front lot"), and the Serranos' property, behind the Bignamis and with no street frontage of its own, is #150 ("#150" or "the back lot"). The shared driveway runs from Tappan Street along the westerly side of the Bignami property to the Serrano property's lot line (hereafter, "the shared driveway" or "the shared part"). The Serrano driveway connects to the shared driveway at the lot line, and runs from there to the site of a former garage on the Serranos' property (hereafter, "the Serrano driveway" or "the Serrano part").

The overall driveway, both the shared part and the Serrano part, has existed since at least 1907, and is shown on a map of Brookline from that year. It was created before the now-Bignami lot and the now-Serrano lot were divided, when both were a single property. The now-Bignami lot contained the main house (now the Bignami residence), and there was a stable behind it located on the now-Serrano lot. The driveway led from Tappan Street past the main house and ended at the stable. The stable was converted into residential space in 1925 (now, considerably renovated, the Serrano residence) and, soon thereafter, a large sub-ground garage was built next to it.

The 1954 ANR plan that divided the formerly single Tappan Street property into these two lots shows a 40'-wide "right of way" from Tappan Street to the Serrano lot that runs along the eastern side of the Bignami lot (hereafter, the "40'-wide right of way"). [Note 1] As soon as the 40'-wide right of way formally became an easement (when the two lots entered into separate ownership later in 1954 with the conveyance of #150 (the back lot)), [Note 2] it was expressly limited to pedestrian use and, by the express terms of the deed, could not even be used for that purpose so long as the shared driveway was "available" for the Serrano lot to use. [Note 3] The shared driveway has, in fact, been the only access either property ever used. The 40'-wide right of way has never been developed, and it has never been used as a way in any capacity, at any time, for any purpose.

The Serrano lot's right to use the shared driveway became irrevocable in 1963 when it was put into a formal easement agreement. That agreement (hereafter, the "1963 Agreement") also included an easement benefiting the Bignami lot which likely reflected an earlier, informal, practice. This agreement gave the owners of the Bignami lot a right to park one vehicle in the then-existing garage on the now-Serrano property, expressly limited to that particular garage, as well as a right to use the Serrano driveway to get to and from that parking space. That particular garage was unique because it was dug into a large slope on the Serranos' yard and had a fenced lawn above it, and was also unique because, although located next to the Serrano house, it was isolated from the house and had no direct access to it. To get to the house, it was necessary to walk back out onto the driveway, climb the slope, and then enter the front door of the house. Moreover, the garage was unusually spacious, with three bays and room for five cars. It fell into disrepair over the years and the town eventually declared it unsafe and ordered its removal. The Serranos complied with this order and demolished the garage soon after they purchased the property. Thereafter, based on their contention that the end of the garage meant the end of the Bignamis' right to park and drive on their land, the Serranos put up a fence blocking the Bignamis' access.

The disputes between the parties are these: (1) the Bignamis' right, if any, to park in any new garage that may be built on the Serrano lot, [Note 4] (2) the Bignamis' right, if any, to use the Serrano driveway to access the new garage, to park where the old garage was formerly located, or, even if no parking right of any kind exists, as a turn-around area for their cars, (3) the Serranos' right to use the shared driveway if the Bignamis no longer have a right to use the Serrano driveway, (4) the Bignamis' right, if any, to pause or stop in the shared driveway, [Note 5] (5) what measures the Bignamis may take with respect to the shared driveway to reduce speed and increase safety, (6) the Bignamis' right to put fences and other barriers alongside the shared driveway so long as they do not block it, and to put a fence along the border between their property and the Serranos' property so long as that fence does not block the shared driveway, (7) the Bignamis' right, if any, to conduct video surveillance of the shared driveway, (8) the Bignamis' right to relocate the shared driveway under MPM Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 (2004) and, if so, where, and (9) the Serranos' right, if any, to use the 40'-wide easement for pedestrian or vehicular access to their lot.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule as follows.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

The Current Use of the Driveways

As noted above, this case involves two neighboring families in Brookline: the Bignamis and the Serranos. The Bignamis live at #146 Tappan Street, and the Serranos at #150. The Bignami property has frontage on Tappan Street. The Serrano property is a "rear lot" without frontage and is located behind the Bignamis' property. [Note 6] Both lots have their own outdoor parking spaces. The Bignamis currently have three such spaces on their property, with room to create more.

The Bignamis have lived at #146 since August 2012. The Serranos moved into #150 in March 2018, after nearly two years of renovation. Both homes use the shared driveway as their sole access to Tappan Street. The driveway is paved with asphalt, is 9' wide at its maximum, and is thus only one car wide. Two cars cannot pass each other on the shared driveway, nor, if they are coming from opposite directions, can one pull over for the other to pass. If a vehicle is stopped or paused anywhere on the shared driveway, no other vehicle can get by as long as that vehicle is stopped or paused.

The Serranos and the Bignamis both have young children. Both sets of children use the shared driveway to walk to and from the street, and the Bignami children also use it to play on. Each of the families has a child with a disability. Vehicles speeding on the driveway are thus dangerous to them, as are even momentarily-inattentive drivers. On one occasion one of the Bignami children came close to serious injury when a construction vehicle speeded down the shared driveway from the Serrano property without stopping. Even that incident did not lead to subsequent vehicles driving consistently more slowly.

Children in both families attend the same school with the same starting and ending times. Both sets of parents thus need to drive them there and bring them home at the same time. Parents in both homes work on similar schedules, others are home with the children, and they, their child-care helpers, their visitors, and their deliveries, come and go to their houses frequently throughout the day at both regular and irregular times. All of these trips are on the shared driveway because there is no other access to either house. The Serranos are delayed - sometimes quite a bit, and sometimes at important times - when the Bignamis pause or stop their cars in the shared driveway to load and unload their children, their shopping, or to go back inside the house to retrieve something forgotten.

The school van that transports the Bignamis' disabled child drives onto and backs out of the Bignami driveway without going onto the Serrano property. The van is never unattended (the driver is always inside), and never creates a conflict for the Serranos because the driver immediately backs down the driveway, out of the Serranos' way, when the Serranos need to leave their house. The relations between the parties themselves are such that they have not similarly cooperated with each other. Nor, as the evidence showed (and I so find), can cooperation between them realistically be expected or relied upon for purposes of determining the appropriate relief to be granted in this case.

As noted above, a now-demolished garage previously existed on the Serrano property, which the owners of the Bignami lot had a right to park a single vehicle inside as long as that garage existed. [Note 7] The Serranos installed a fence blocking access to the area occupied by the former garage soon after its demolition. Until the garage was demolished, the Bigmanis would drive over the Serrano driveway when they wanted to use their parking space. The cars parked on the Bignami property itself would turn around using "k" turns on the shared driveway without driving onto the Serrano lot. To the extent the Bignamis claim that they drove onto the Serrano lot just to turn around, I do not believe them.

The Creation of the Easements at Issue in this Case

As noted above, the Bignami and Serrano properties were originally a single lot, with one house and its associated stable, owned by Edith May. The stable was converted into a dwelling space in 1925, which Ms. May used as an artist's studio. In 1954, after Ms. May's death, her executor filed an ANR plan that divided the property into two lots. The original house continued to be numbered 146 Tappan Street, and the studio building, formerly the stable, became #150. The executor then conveyed both lots to Benedict and Ethel Alper, and the lots remained in their common ownership until later that year.

The ANR plan showed a 40'-wide "right of way" over the eastern side of #146, and the deed from Ms. May's executor to the Alpers referenced it. But no actual easement was created at that time, either express or implied, because the two lots remained in common ownership and an easement that purports to burden one part of commonly-owned land for the benefit of another commonly-owned part cannot legally exist. See Ritger, 62 Mass. at 147 (easements are eliminated "by the unity of title and possession, both of the dominant and servient tenements, in the same person" at the same time). Such an easement did not exist until June 24, 1954 when the Alpers conveyed #150 to George and Janet Faxon, and the grant of that easement expressly limited it to pedestrian use, and even that use only when the use of the shared driveway to access #150 was no longer "available." The precise language of the grant was as follows:

This conveyance is subject to a 40-foot Right of Way over the Easterly side of Lot A [#146 Tappan Street, where the Alpers continued to live], as shown on said plan, extending from Tappan Street to said Lot B [#150, the lot conveyed to the Faxons], for the benefit of Lot B, to be used for pedestrian traffic only. Provided however, and it is specifically covenanted and agreed that said 40-foot Right of Way shall not be used for any purpose by the owners . . . of said Lot B [150 Tappan Street], . . . so long as the present existing driveway from Tappan Street across the westerly side of Lot A [146 Tappan Street] to the building in the rear of said Lot B is available for all purposes for which driveways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline; it being a further covenant, agreement, and condition that each owner shall maintain so much of said driveway as lies within the confines of said owner's lot. [Note 8]

Put simply, the Faxons and their successor owners of #150 were granted a pedestrian-only easement over the 40' right of way which would not take effect so long as the "present existing driveway" (the shared driveway) was "available" for them to use "for all purposes for which driveways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline." That driveway - the shared driveway - has been the sole access to #150 from that time to the present, and continues to be so.

On June 19, 1959, the Faxons deeded #150 to Edward and Regina Barshak without changing the rights and easements as they existed between the properties. [Note 9] Four years later, on February 28, 1963, the Barshaks conveyed #150 to Henry and Barbara Moses, again without altering the rights and easements. [Note 10]

The Moses wanted their right to use the shared driveway to be affirmatively stated and irrevocable. Thus, on March 14, 1963, soon after they purchased #150, they and the Alpers (who had continued to own #146) entered into the 1963 Agreement "to grant certain rights over the existing driveway from Tappan Street to the rear of Lot B [#150]". [Note 11] This agreement included the formalization of what was likely an existing arrangement regarding the garage on #150. The Moses to Alper grant gave the Alpers and their successors:

the right to use the present existing driveway from Tappan Street across the westerly side of Lot A [#146] to the garage building in the rear of Lot B [#150], to the extent said driveway lies within the confines of Lot B [i.e., the Serrano driveway], for all purposes for which driveways and footways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline. The said Moses further grant and convey . . . the right to park one motor vehicle in that stall of the garage building in the rear of Lot B which is closest to Lot A; but only so long as the garage building is standing, there being no obligation to repair or rebuild said garage.

The Alper to Moses grant gave the Moses and their successors:

the right to use the present existing driveway from Tappan Street across the westerly side of Lot A to the garage building in the rear of Lot B, to the extent said driveway lies within the confines of Lot A [i.e., the shared driveway], for all purposes for which driveways and footways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline.

No mention was made of the 40'-wide pedestrian-only easement from 1954, but the fact that the shared driveway easement was now irrevocable (and thus the shared driveway would always be "available") shows the mutual intent to abandon it.

In 1994, the executor of Mr. Alper's estate [Note 12] deeded #146 to Mark and Mary Canner without change to its then-existing easements or driveway rights. [Note 13] Six years later, in 2000, the Canners conveyed #146 to David and Victoria Register, without further change. [Note 14] And in 2012, the Registers conveyed #146 to the current owners, the Bignamis, again without change. [Note 15]

In 2016, the trustee of Mrs. Moses' trust (to which the Moses had transferred ownership of #150) conveyed #150 to the current owners, the Serranos, with no reference at all to its rights and easements. [Note 16] By operation of law, this nonetheless conveyed all such rights and easements as then existed. See G.L. c. 183, §15 ("In a conveyance of real estate all rights, easements, privileges and appurtenances belonging to the granted estate shall be included in the conveyance, unless the contrary shall be stated in the deed, and it shall be unnecessary to enumerate or mention them either generally or specifically.").

The Demolition of the Former Garage on the Serrano Property

For safety reasons, the old garage on the Serrano property was demolished soon after the Serranos bought the lot. Since the garage no longer existed, this ended the Bignamis' ability to park a car inside it, and the Serranos erected a fence across their driveway blocking all access to the area formerly occupied by the garage. The Bignamis contend that they have a right to a parking space in any new garage if and when one is built, and at least the right to go onto the Serrano property to turn their vehicles around. The Serranos contend otherwise.

Stopping and Pausing in the Shared Driveway

The Bignamis currently have three outdoor parking spaces on their property, two on the eastern (house) side of the driveway and one on the other side of the driveway, and have room behind their house to create more. [Note 17] They typically load and unload their cars from these spaces, but also do so while paused or stopped in the shared driveway. This pausing or stopping in the driveway occurs mostly when they are loading or unloading their children from their cars, and they do it intentionally to block vehicles from using the shared driveway while they are doing so. Their loading and unloading in the driveway takes anywhere from one to fifteen minutes, and often delays the Serrano family who are trying to leave their home at the same time. It would not be necessary if the Bignamis enlarged the parking area on the "house" side of their property or if they simply had fewer cars parking there (they currently own three cars, for two drivers), both of which are feasible and reasonable alternatives that would give them more than adequate safe space to load and unload without blocking the driveway. Blocking the driveway for the safety of their children while loading and unloading them would also not be necessary if effective speed-calming devices are installed on the shared driveway itself.

Attempts to Reduce Speed on the Shared Driveway

The Bignamis have young children, and thus have serious and legitimate concerns about speeding and inattention on the shared driveway. As noted above, their youngest son came close to being struck by a large, fast-moving truck leaving the Serrano property during the Serranos' house renovations, and speeding has not been confined to just construction-related vehicles. Delivery trucks and visitors' cars have sped as well. As a result, the Bignamis have tried a variety of traffic-calming measures to reduce speed on the shared driveway.

In Summer 2017, during the height of the two-year renovations of the Serrano house, the Bignamis put a sign on the shared driveway that read, "Drive Like Your Kids Live Here" and a bright yellow figurine with a flag that read, "Slow. Child." These signs were ineffective. They were frequently moved (not by the Bignamis), and later stolen. Ms. Bignami personally spoke to the Serranos' general contractor and other construction workers about her concerns for her children and implored them to drive slowly. They agreed to instruct their vendors and workmen to drive slower, but their speeding continued nonetheless. After this, the Bignamis installed speed bumps.

There are currently three speed bumps on the shared driveway, installed by the Bignamis in stages between Fall 2017 and Spring 2018. [Note 18] The first speed bump is located near Tappan Street to slow vehicles as they enter the shared driveway. The second is located just before the Bignamis' parking areas to ensure that vehicles have not sped up when they reach that point. The third is near the Serranos' property line, to ensure that vehicles entering the driveway from that direction do not speed. I find that each is reasonable and necessary to ensure that cars and trucks drive slowly on the driveway, and that none of them, singly or as a group, unreasonably interfere with the Serranos' use of the driveway.

The Bignamis started with 2"-high plastic speed bumps, but later changed to 3"- high rubber ones when the shorter screws in the smaller speed bumps became dislodged. The shorter speed bumps were also replaced because they were insufficient to adequately slow vehicles on the driveway. A visitor to the Serrano house tripped over one of the speed bumps while walking down the shared driveway at night, but the Bignamis have since solved this problem by installing solar lights on both sides of each speed bump to clearly mark and illuminate their location.

Fences and Visibility

The Bignamis have installed a 6'- high wooden fence on the property line between their house and the Serranos', with an opening for the shared driveway. After an incident where the Serranos' daughter was choking and the Serranos expressed concern about the visibility of their home to emergency vehicles, the Bignamis removed alternating slats from that fence to increase visibility. This has satisfied the Serranos.

The Bignamis also installed a short mesh fence along the western edge of the shared driveway to keep vehicles from driving off the edge of the driveway onto their grass. This mesh fence has since been replaced with cinder blocks, which achieve the same purpose.

Neither the fences nor the cinder blocks enter or cross the shared driveway. Further, neither the fences nor the cinder blocks prevent any person or vehicle from entering or exiting the shared driveway. Notably, they have not prevented any mode or method of access that existed prior to their installation.

Video Surveillance

The Bignamis installed four motion-activated surveillance cameras covering the entirety of the shared driveway, three with both audio and video capabilities. [Note 19] Camera one was installed on a tree by the Bignamis' house facing Tappan Street. Camera two was installed on the Bignamis' fence so that it faced the back of the shared driveway in the direction of the Serrano house. Camera three was installed on the stockade fence along the property line between the two houses, recording all traffic and pedestrians coming onto the shared driveway from the Serranos' property. Camera four was a so-called "nanny camera", but instead of being pointed into the Bignami living spaces (thus showing the children's activities with their caregiver), it was pointed out the window to cover the driveway.

The Bignamis installed these cameras purportedly for security reasons -- they have left their cars unlocked, and intruders have come up the driveway on dark nights and opened the car doors to take items left inside -- but primarily to monitor the Serranos' use of the shared driveway. [Note 20] This inevitably captures the Serranos' children when they are on the driveway, either by themselves or with their parents.

Footage collected by these cameras is stored "in the cloud" by a company with whom the Bignamis have a monthly contract, and can be viewed by anyone with the password to log-in and access the videos. Video is stored for 30 days before being automatically deleted. The Bignamis review all of this footage at least weekly and have the option of downloading any of it they wish. They have used camera footage in this court, and also at hearings before the Brookline municipal boards in connection with their opposition to the Serranos' permit applications.

During the course of these proceedings, I entered a preliminary injunction prohibiting the Bignamis' audio and video surveillance of the shared driveway and, after that injunction was entered, the Bignamis re-directed the cameras so that they covered only the Bignamis' house and their parking areas. That injunction, and the reasoning behind it, are discussed more fully below. Further facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

The 1963 Agreement between the Alpers and the Moses is at the center of this case, with its interpretation and application determining all of its issues. As previously noted, it has two parts -- the first, which granted the Bignami lot certain rights with respect to the Serrano property, and the second, which governs the use of the shared driveway on the Bignami lot. I address them in that order.

The Bignamis' Rights in the Serrano Property

I begin with the question of whether the demolition of the old garage on the Serrano property terminated the Bignamis' right to park on the Serranos' land (whether in any newly-built garage or in an outside area), and the related question of whether it terminated the Bignamis' right to go onto the Serrano land for that purpose or any other. Those questions are governed by the 1963 Agreement, which states as follows with respect to the Serrano property:

Harry Moses and Barbara Moses, husband and wife, hereby grant and convey to Benedict S. Alper and Ethel Alper, . . . , their heirs, assigns and successors the right to use the present existing driveway from Tappan Street across the westerly side of Lot A [#146] to the garage building in the rear of Lot B [#150], . . . , for all purposes for which driveways and footways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline. The said Moses further grant and convey to said Alpers, their heirs, assigns, and successors the right to park one motor vehicle in that stall of the garage building in the rear of Lot B which is closest to Lot A; but only so long as the garage building is standing, there being no obligation to repair or rebuild said garage.

(emphasis added).

When interpreting the meaning of such grants, courts look to the words of the instrument to discern the intent of the grantor, White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 410-11 (2013), and those words are to be interpreted in their "usual and ordinary sense," DeWolfe v. Hingham Centre Ltd., 464 Mass. 795 , 803 (2013) (internal citations omitted), and in a "common sense" manner, Cadle Co. v. Vargas, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 361 , 366 (2002) (internal citations and quotations omitted). [Note 21] Here, that language specifically states that the Bignamis' right to park continues "only so long as the garage building" is standing (emphasis added). This functions as a temporal limitation for the parking easement, automatically terminating the right when that garage is no longer there. That garage has now been demolished, and is gone. The right to park has thus ended.

This is clear not only from the language of the grant, but also because it makes perfect sense. As noted above, the now-demolished garage was unique. It was large with many bays, was dug into the hillside, and, most importantly, was completely separate from the Serrano house with no doorway or other access to it. Thus, the privacy and security of the house was unaffected if a stranger's car parked inside the garage. That style of garage is extremely uncommon today. The function of a residential garage is to protect vehicles from the weather and, just as importantly, to allow the residents of the house access to their vehicles without themselves being exposed to the cold, rain, and snow. Any new garage on the Serrano property will thus almost certainly have a direct entrance to the house. It will also, almost certainly, be smaller.

The Bignamis argue that the specific inclusion of the phrase "there being no obligation to repair or rebuild" means that if the structure is rebuilt then the Bignamis' right to park one vehicle in it would continue. I disagree. Contrary to the Bignamis' assertion, the specified lack of an obligation to repair or rebuild shows that, once the existing structure is damaged or destroyed, the Bignamis' limited rights have ended and they can make no further demands on the Serranos. Had the easement extended to a rebuilt garage it would have said so affirmatively, and the fact that it did not is easy to understand. As just noted, the old garage was unique. It had room for five cars, and it was completely separate from the Serrano house with no doorway or other access to it. [Note 22] In the absence of explicit language, it would be extraordinary to grant a stranger a right to park in a new garage that had such direct access, given the intrusion on privacy and seclusion that would result. [Note 23] In the absence of explicit language, it would also be extraordinary to require any rebuilt garage to be larger than the homeowner needed just to accommodate a stranger's car.

Since the Bignamis' right to a parking space in the now-demolished garage has ended, so too has their right to drive onto the Serrano property. The clear purpose of the driveway easement was to provide the owner of #146 with access "to the garage building" in which they had a parking easement. The language of the grant expressly ties them together. When an easement is incapable of being exercised for its originally intended purpose, the easement right is extinguished. Makepeace Bros. v. Town of Barnstable, 292 Mass. 518 , 525 (1935). Here, the driveway easement was created for the purpose of allowing the owners of #146 to access the garage. Since the garage no longer exists, the easement rights, limited to accessing the demolished garage, have come to their prescribed conclusion. See id. (holding that easement rights created for the purpose of whaling were extinguished when the whaling industry disappeared); Cotting v. Boston, 201 Mass. 97 , 101-02 (1909) (noting that, when an easement is granted for purpose of passing and repassing to a specific building, "a right of way through a building, in the absence of plain words to the contrary, incumbers the servient estate only so long as the building exists described in the instrument creating the right of way. We can think of no sound principle of law which prevents the extinction of a right of way with the destruction of the building upon the dominant estate, when it seems reasonable that such was the intention of the parties.").

Furthermore, in determining the scope of an easement, the court looks to the language of the grant "in the light of the attending circumstances which have a legitimate tendency to show the intention of the parties as to the extent and character of the contemplated use." Doody v. Spurr, 315 Mass. 129 , 133 (1943); see White, 464 Mass. at 410-11 (quoting Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007)) ("The basic principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that their meaning, derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances."). As noted above, the language of the grant indicates that its purpose was exclusively for access to the garage. This is exactly the way, and the only way, it was used by the original grantees, the Alpers. Joshua Alper (the nephew and executor of the Alpers, who regularly visited their home) testified that the driveway easement over the Serrano property was only ever used to access the parking space in the former garage and was never used as a general turn-around for the Alpers' cars. When the Alpers turned the cars around that they parked on their property, they did so using a backing-up "k-turn" into the shared driveway on #146. [Note 24] The Bignamis' use of the Serrano driveway on #150 is too far removed from the granting parties' use to be relevant for the interpretation of the granting parties' intent. Boudreau v. Coleman, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 621 , 632 (1990) ("Where the intent is doubtful, the construction of the parties shown by the subsequent use of the land may be resorted to, if such use tends to explain or characterize the deed, or to show its practical construction by the parties, providing the acts relied upon are not so remote in time or so disconnected with the deed as to forbid the inference that they had relation to it as parts of the same transaction or were made in explanation or characterization of it.") (internal quotations omitted). Furthermore, to the extent the Bignamis claim they made a regular practice of driving onto the Serrano property solely to turn around the vehicles that they parked on their own land, I do not believe them.

For these reasons, I find that the Bignamis' right to go onto the Serrano property ended when the old garage was demolished, and that the Bignamis have no right to park in any new garage or outside area on the Serrano land.

The Existence and Scope of the Serranos' Easement over the Shared Driveway on the Front Lot

The second part of the 1963 Agreement sets forth the Serranos' rights in the shared driveway on the front lot (the Bignami property at #146). As noted above, that Agreement grants the Serranos:

the right to use the present existing driveway from Tappan Street across the westerly side of Lot A [#146] to the garage building in the rear of Lot B [#150], to the extent said driveway lies within the confines of Lot A [i.e., the shared driveway], for all purposes for which driveways and footways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline.

This shared driveway is, and has always been, the Serrano property's sole access to the street.

The Bignamis argue that the expiration of their easement on the Serrano land also ended the Serranos' easement over the shared driveway on their lot -- an argument that the two are linked and the end of one necessarily ends the other. I disagree. The two sets of rights are independent of each other, and were clearly intended so. This is apparent from the language of the Agreement and, in particular, the differing nature of the two grants.

The right of the owner of #150 to use the shared driveway does not include any temporal or other limitation. Nor, given that the shared driveway is #150's only access to the street, can any such limitation logically or sensibly be implied. The need to use it is perpetual. See Cadle Co., 55 Mass. App. Ct at 366 (contracts to be given "common sense" interpretation). Making this right of access irrevocable -- not just existing when the driveway was made "available," as the 1954 agreement had previously provided -- was a clear motivating intent when the new agreement was negotiated and signed in 1963.

In contrast, the right to park on #150 that was granted to the owner of #146 does have an express limitation, and it is plainly stated. That right exists "only so long as the garage building is standing, there being no obligation to repair or rebuild said garage." That garage is now gone. As a result, the purpose for which the owners of #146 had driveway access to the rear lot ended and, accordingly, so too did their driveway easement. See Makepeace Bros., 292 Mass. at 525 (holding that once an easement's purpose is gone the right comes to an end).

The attendant circumstances of the 1963 Agreement also support this reading of the clear language. White, 464 Mass. at 410-11 (holding that words used in a written instrument can be interpreted, when necessary, based on attendant circumstances). The Alpers did not use the Serrano property for any purpose other than accessing the garage. Even the Registers, who owned #146 just before the Bignamis, did not go on the Serrano lot for any other purpose. In contrast, the owners of #150 have always used the "existing driveway from Tappan Street across the westerly side of Lot A" in order to access their otherwise landlocked parcel, and (unlike the demolition of the garage) no circumstance has occurred that caused the easement's clear purpose -- rear lot access to a public street -- to end. See Comeau v. Manzelli, 344 Mass. 375 , 381 (1962) (finding that an easement to pass and repass from grantee's property to a public way has the purpose of providing access to the way). [Note 25]

Unreasonable Interference with Easement Rights

For the reasons set forth above, the Serranos continue to have an easement to use the shared driveway. The question now becomes what can be done in the shared driveway, and what must be prohibited, in light of that easement. The analysis begins with the basic principles of easement law.

Easements have a "servient" estate and a "dominant" estate. The servient estate is the one burdened by the easement (here, the Bignami property), and the dominant estate is the one that benefits from it (here, the Serrano lot). See Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 524 n.5 (2012) (citing MPM Builders, 442 Mass. at 88 n.2). When an easement is created it includes by implication every right necessary for its enjoyment. Sullivan v. Donohoe, 287 Mass. 265 , 267 (1934). But the owners of the servient estate retain the full right to use their property in any and all ways that do not materially interfere with the easement's use. Merry v. Priest, 276 Mass. 592 , 600 (1931). See also Ampagoomian v. Atamian, 323 Mass. 319 , 322 (1948) (servient estate may use its land for all purposes except where inconsistent with the easement); Perry v. Planning Bd. of Nantucket, 15 Mass. App. Ct. 144 , 158 (1983) ("[The] owner [of the servient estate] may use the land for all purposes which are not inconsistent with the easement . . . or which do not materially interfere with its use.") (internal quotations omitted).

Applying these principles, I turn to the specific issues that have arisen regarding the use of the shared driveway: the Bignamis' right, if any, to stop or pause their cars in the driveway;

their right, if any, to install and maintain speed bumps or other speed-reducing measures in the driveway; their right, if any, to install and maintain a fence or other barrier along the borders of the driveway to keep vehicles from driving off it onto their landscaping; their right, if any, to install and maintain a fence between their property and the Serranos' so long as the fence does not block the driveway; and their right, if any, to conduct video surveillance of the driveway. Stopping or Pausing in the Shared Driveway

The Bignamis own the fee in the shared driveway. Fee ownership generally includes the right to temporarily pause or park in the easement area, but not when "it would interfere with the [easement holder's] right of ingress and egress of the way." DeNadal v. Beauregard, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 1139 , 2013 WL 3233466 at *2, n.8 (2013). See also Brassard v. Flynn, 352 Mass. 185 , 189 (1967) (fee owner may temporarily park a vehicle on a shared way, but only if it is not a substantial obstruction to the easement holder's ingress and egress); Poller v. Brewster, 9 LCR 207 , 209 (Mass. Land Ct. 2001), amended by Poller v. Brewster, 9 LCR 288 (Mass. Land Ct. 2001) (right to make temporary stops incident to travel or for the purpose of loading and unloading passengers and property only exists so long as it does not "interfere unreasonably with the rights of others with rights of passage to make use of the way.").

Here, because of the narrowness of the shared driveway, any stop or pause is a total and complete obstruction of ingress or egress for the complete duration of the stop or pause. For the Serranos, there is no room to maneuver around the stopped vehicle while staying within the easement. This severely prejudices the Serranos, who have no other way to get to or from their home. A one to fifteen minute delay may not seem like much in the abstract, but it can be critical when children need to be taken to school, when work schedules need to be met, when an emergency arises, and when it may occur multiple times during the day or night. It is unreasonable to hold the Serranos' schedules hostage to the convenience of the Bignamis, and there is no persuasive justification for doing so. The Bignamis have plenty of parking space on their land (three spaces at present, two of them immediately outside their doorway), and have room to create more next to their house. They thus have no need to stop in the shared driveway itself. [Note 26] The evidence showed that the parties cannot be relied upon to cooperate with each other, nor could such cooperation solve the problem. This is because the Bignamis are often not in their cars when they are stopped or paused in the shared driveway. They may be back in their house to retrieve something forgotten, or in the process of getting their children, groceries, or shopping into and out of their house.

Accordingly, with the exception of the school van that picks up the Bignamis' disabled child at the same, set time in the morning and has not been a problem for the Serranos to schedule around, there shall be no pausing or stopping of any vehicle in the shared driveway, at any time, for any duration, no matter how brief. I find that this is the only workable solution and that it is necessary to protect the Serranos' right of free access over the easement. Allowing the Bignamis to pause or stop in the shared driveway, even for short periods of time, would materially interfere with the Serranos' easement rights, and prohibiting such pauses or stops is not an unreasonable burden on the Bignamis.

Speed Bumps in the Shared Driveway to Reduce Speeding

I turn next to whether the Bignamis' three 3"-high rubber speed bumps unreasonably interfere with the Serranos' use of their express easement over the shared driveway, and find that they do not.

The Bignamis have shown a compelling reason for reducing speed. Not only is this necessary for their safety in general, it is also a particular need for their children who play next to the house near the driveway and in the driveway itself, and even more particularly for their disabled child. Speeding is a continuing problem on the driveway, not only from construction vehicles during renovations of the Serrano home [Note 27] but also, on a regular and continuing basis, from delivery vehicles going to and from the Serrano house and, for that matter, to the Bignamis'. Even visitors' vehicles drive too quickly on the driveway. Signs have been ineffective. Physical "bumps" are needed to actually reduce speed and, just as importantly, to remind drivers that they must slow down.

Such "bumps" are not unreasonable. They have not interfered with vehicles going to and from the Serrano property. No vehicle has been unable to go over them. [Note 28] No vehicle has been damaged by the bumps. All that the bumps have done is slow those vehicles down. Shorter bumps, with shorter screws, have become dislodged. The 3" bumps with longer screws have not, and are more effective at slowing vehicles down without materially adding to the "bump" that drivers feel. Speed reduction measures have been ordered by judges of this court in similar situations. See, e.g., Wright v. Patriakeas, 18 LCR 453 , 453 (Mass. Land Ct. 2010) (Sands, J.) (enjoining placement of any item in an easement except for speed bumps and speed limit signs); Wylan v. Matthews, 10 LCR 258 , 259 (Mass. Land Ct. 2002) (Sands, J.) (implementing speed limit on shared driveway).

Two issues have arisen with the bumps, both easily addressed.

The first is their illumination. A visitor to the Serranos tripped over one of them in the dark, and vehicles should have fair warning of their presence in order to know to slow down. Thus, the Bignamis have installed lights on both sides of each of them. Such illumination must continue, and is hereby made a condition of the Bignamis being allowed to maintain the bumps in place.

The second is one that arises during snow season. The driveway needs to be plowed, and the bumps make it difficult to plow. They will either hinder the plowing or become damaged and dislodged by the plows. The Bignamis have committed to removing the bumps whenever it snows, and whenever they will be away from their property during wintertime for extended trips. This, at a minimum, is what they must do. My concern is that this may prove unworkable in practice. Snowfalls are not always predictable, the Bignamis may not have removed the bumps beforehand, and they may not be around to remove them when the snow arrives and plowing is necessary. A permanent solution is far preferable -- a traffic calming "table" that plows can go over, and is still enough of a "bump" to slow vehicles down. For now, the 3"-high rubber bumps are allowed, but if any snowplowing problem occurs they must be removed and replaced by traffic-calming tables as described above or the alternate measures described below.

The Bignamis have proposed two alternate measures, specifically (1) the installation of two 4" asphalt speed bumps, one on each side of their parking areas, which will be durable enough to withstand snowplowing with caution, and (2), as a longer-term solution after the Serranos complete their renovations, the resurfacing of the shared driveway with asphalt, the installation of a concrete speed bump with a 4" reveal near the property line between the two properties, and the installation of a 4" high, 10' long speed table with 3' transition ramps on both sides located between the Bignamis' parking areas and Tappan Street. [Note 29] These too are acceptable and may be implemented. So long as they, too, are illuminated so that their locations are apparent, they are not unreasonable and they will not interfere with the Serranos' access over the easement.

The Installation of a Border Fence, and Fences or other Barriers Along the Shared Driveway

I turn next to whether the Bignamis' installation of a fence along the border between the properties, and whether their installation of a mesh fence or cinder blocks along the edges of the shared driveway, impermissibly interfere with the Serranos' express easement.

The most obvious initial issue is this: do any of them cross or block the shared driveway? If so, they would be prohibited. As discussed above, the shared driveway is simply too narrow to allow any blockage, anywhere, at any time. See World Species List-Natural Features Registry Inst. v. Reading, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 302 , 310 (2009) (while servient estate owners "enjoy rights to use their land, they may not engage in activities that are inconsistent or materially interfere with a dominant owner's easement."). Here, however, neither the boundary line fence nor the mesh fence/cinder blocks cross or block any part of the driveway. The boundary line fence has an opening the full width of the driveway, and the mesh fence and cinder blocks were placed along the driveway's edges. None are on the driveway itself. "[T]he owner of the servient estate may fence the sides of [a] way" which is encumbered by an easement to pass and repass. Ball v. Allen, 216 Mass. 469 , 472 (1913). The Bignamis' fences and cinderblocks are reasonable because they exist to demarcate property lines and prevent people from driving off of the shared asphalt driveway and onto the Bignamis' yard area. See Rendell v. Mass. Dep't of Conservation & Rec., 17 LCR 734 , 746 n.55, 2009 WL 4441212 at *18 n.55 (Mass. Land Ct., Dec. 2, 2009), aff'd 81 Mass. App. Ct. 1138 (2012) (Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28).

A related issue is whether the fence along the property line or the mesh fences/cinder blocks along edges of the shared driveway impair the sight-lines of the driveway. Put simply, while vehicles are on the shared driveway proceeding at the slow speeds directed above, do the property line fence or the mesh fence/cinder blocks along the edge of the driveway impair the driver's ability to see the driveway itself? If so, this would be a material impairment of the Serranos' easement rights. Again, none of them do, and the Bignamis have placed poles along the edges of the driveway so that the edges are clearly visible in the snow or rain.

The Serranos have objected to the property line fence insofar as it obscures the view of their house as seen from Tappan Street. But keeping an open view of their house is not a part of their easement rights, which only concern the driveway itself and the access it provides. In any event, the Bignamis have voluntarily removed every other slat from the fence, which enables the Serrano house to be seen more easily.

In sum, none of these fences or cinder blocks interfere with the Serranos' easement rights, and thus they may remain.

Video Surveillance of the Shared Driveway

I turn next to the question of whether the Bignamis' video surveillance of the shared driveway is an unreasonable and material interference with the Serranos' easement rights to its use. I find and rule that it is, most particularly because it inevitably surveils the Serranos' minor children and the Serranos' interactions with their children on the Serranos' own private property (their express easement) -- a type of privacy and a place of privacy that the law especially protects.

In reaching this conclusion I looked at Massachusetts privacy law generally, including cases under the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act (G.L. c. 12, §§11H & I), the Massachusetts Privacy Law statute (G.L. c. 214, §1B), and those involving the privacy of children and the parent/child relationship, and applied their guidance to the property rights at issue here. As those cases show, conduct on the part of the servient estate that forces the holders of a dominant estate to avoid, limit, or fear the use of their rights is fundamentally inconsistent with the existence of an easement and materially interferes with its use, particularly when children are involved. See Ayasli v. Armstrong, 56 Mass. App. Ct. 740 , 743-45 (2002) (holding that defendant violated Massachusetts Civil Rights Act, inter alia, by videotaping neighbors because this and other actions made the neighbors want to abandon their renovation and thus interfered with their right to use and enjoy their property); Yagjian v. O'Brien, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 733 , 735 (1985) ("The cases on this subject have tended to weigh slight inconvenience to the dominant owner's use of the way against the servient owner's freedom to use his property in a reasonable manner for his own benefit and convenience and to strike an equitable balance."); Moses v. Cohen, 15 LCR 41 , 47 (Mass. Land Ct., 2007) (noting that, in the context of relocating an easement, a decrease in privacy burdens the enjoyment of the easement). See generally Quilloin v. Walcott, 434 U.S. 246, 255 (1978) (relationship between parent and child constitutionally protected; "freedom of personal choice in matters of family life is one of the liberties protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment") (quoting Cleveland Bd. of Education v. Lafleur, 414 U.S. 632, 639-640 (1974); Custody of a Minor, 375 Mass. 733 , 748 (1978) ("These natural rights of parents [to raise their children according to the dictates of their own consciences] have been recognized as encompassing an entire 'private realm of family life' which must be afforded protection from unwarranted State interference.") (citing Quilloin, supra); Guardianship of Kelvin, 94 Mass. App. Ct. 448 , 453 (2018) ("It is well established that parents have a fundamental liberty interest in the care, custody, and management of their children.") (internal citations and quotations omitted).

Violations of the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act require interference or attempted interference with protected rights by "threats, intimidation, or coercion." G.L. c. 12, §§11H & I; Swanset Dev. Corp. v. Taunton, 423 Mass. 390 , 395 (1996). Thus, it is particularly instructive when, even in the context of this high burden, courts have found video surveillance of others to be such a violation. Such was the case in Ayasli, an action with many parallels with this one.

In Ayasli, among other things, the defendant consistently opposed the plaintiff's development plans before town boards (so have the Bignamis here), took photographs of the plaintiff's house (so have the Bignamis here, during one of the Serrano children's birthday parties), and threatened more extensive videotaping of the plaintiff's activities (here, any motion of any kind on the driveway activated the Bignamis' videotaping). 56 Mass. App. Ct. at 742-45; see Haufler v. Zotos, 446 Mass. 489 , 507-08 (2006) (describing the conduct in Ayasli as a standard for violating enjoyment of property rights in the context of a Massachusetts Civil Rights Act claim). This was found to violate Ayaslis' right to use and enjoyment of their property because this conduct constituted "persistent efforts to disturb the plaintiffs' enjoyment of their land, to impede access, limit use, and generally make the Ayaslis so uncomfortable in that secluded location that they would abandon their plans for the house." Ayasli, 56 Mass. App. Ct. at 753.

Federal statutes also protect children's privacy. The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 established federal rules to protect the privacy of children by requiring parental consent for websites that collect a child's data, thereby putting parents in control over the information collected from their children online. The statute covers personal information collected online from an individual under the age of 13, and includes a "photograph, video or audio file where such file contains a child's image or voice" in its definition. 16 C.F.R. §312.2. The purpose of enacting this legislation was to protect children's privacy online, specifically children under 13 years old (which the Serranos' children are). See 16 C.F.R. §312 et seq. Here, the Bignamis were collecting the personal information of the Serrano children by videotaping them and their interactions with their parents and other caregivers while on the shared driveway, uploading those images to a third-party's website (the company storing those images), and occasionally storing those images themselves.

Another federal privacy law that protects the privacy of the parent/child relationship is the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) that gives parents protections with regard to their children's educational records including report cards, disciplinary records, and contact and family information. See 34 C.F.R. Part 9. The law allows parents the right to review their children's records and requires that schools obtain parental consent before disclosing personally identifiable information. See id.

Massachusetts also has similar laws recognizing and protecting children's privacy and a parent's right to raise them without intrusion by others. Pursuant to G.L. c.71, §34D, for example, the Massachusetts Department of Education has promulgated regulations to ensure parents' and students' rights of confidentiality over student records. See 603 Mass. Code Regs. §23.01. Similar to COPPA's focus on consent, third persons may only access student records with consent from the student or their parents. See 603 Mass. Code Regs. §23.07(4); Commonwealth v. Buccella, 434 Mass. 473 , 477 (2001). A further example of concerns and protections for children's privacy comes from our Juvenile Court system. Pursuant to the state's right to adjust its legal system to account for "children's vulnerability and their needs for concern . . . sympathy, and . . . paternal attention," Bellotti v. Baird, 443 U.S. 622, 635 (1979), Juvenile Court proceedings and records in Massachusetts are closed to the public "[t]o preserve the confidentiality of those charged." Commonwealth v. Walczak, 463 Mass. 808 , 828 n. 21 (2012); see also G.L. c.119, §65; G.L. c.119, §60A.

The Massachusetts privacy statute (G.L. c.214, §1B) is also instructive on why the continuous non-consensual videotaping of parents and their children, on their own private property (their express easement) to which the public has no right of access, should be (and is) prohibited as a matter of property law in the circumstances of this case. As G. L. c. 214, §1B provides: "A person shall have a right against unreasonable, substantial or serious interference with his privacy." Intrusion on solitude and the violation of a person's interest in being left alone are actionable under the statute, which is stated in broad terms "so that the courts can develop the law thereunder on a case-by-case basis, by balancing relevant factors . . . and by considering prevailing societal values." Schlesinger v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 409 Mass. 514 , 517, 519 (1991). See also Bratt v. International Business Mach. Corp., 392 Mass. 508 , 509-510 (1984) (balancing defendant's legitimate business interest in disseminating private facts against the nature and substantiality of the intrusion to the plaintiff).

In determining whether there is a constitutional right to privacy in a particular situation, courts look at whether an individual's expectation of privacy in those circumstances "is one which society would recognize as reasonable." Commonwealth v. Simmons, 392 Mass. 45 , 48 (1984) (internal citations omitted). For purposes of privacy law, a driveway is considered a semi-private area, whereby the "expectation of privacy which a possessor of land may reasonably have while carrying on activities on his driveway will generally depend upon the nature of the activities and the degree of visibility from the street." Id. Here, the Serranos have such a reasonable expectation. This is their and their children's only means of access to the street. This is a place where they regularly interact with their children, both when walking and driving. And as shown by the difficulties experienced by the ambulance coming to the Serrano home when their daughter was choking, the driveway is not open and obvious from Tappan Street. Rather, it is narrow, down-sloping, curved, and bordered by trees and shrubbery.

In an escalating dispute between neighbors not unlike this one, the Supreme Judicial Court used the Bratt balancing test by assessing "the extent to which the defendant violated the plaintiff's privacy interests against any legitimate purpose the defendant may have had for the intrusion." Polay v. McMahon, 468 Mass. 379 , 383 (2014). Factors such as "the location of the intrusion, the means used, the frequency and duration of the intrusion, and the underlying purpose behind the intrusion" go into that balancing. Id. In Polay, a neighbor installed cameras that recorded the home of their neighbor across the street on a continuous basis, and the court ruled that this conduct presented a claim for invasion of privacy. Id. at 383. As the Court emphasized, "[n]owhere are expectations of privacy greater than in the home, and in the home all details are intimate details." Id. at 383-384 (emphasis in original) (internal quotations omitted). Even beyond the home, the Court noted, "even where an individual's conduct is observable by the public, the individual still may possess a reasonable expectation of privacy against the use of electronic surveillance that monitors and records such conduct for a continuous and extended duration." Id. at 384 (emphasis added).

Here, like Polay, the video surveillance, triggered by motion of any kind, is continuous and pervasive. It is surveillance of the Serranos on their own private property (their easement). And, in addition, it inevitably records the Serranos' children and the Serranos' interactions with their children -- a constitutionally recognized and protected "private realm of family life" that can only be intruded upon in compelling circumstances. See Custody of a Minor, 375 Mass. at 748; Quilloin, 434 U.S. at 255. Making it worse is the fact that the surveillance footage is stored in the cloud, accessible to anyone with the password (or who can "hack" it), and may be archived by the Bignamis for use on any occasion, in any setting, they choose.

The Bignamis defend this invasion of privacy by claiming they need it to deter speeding, to protect their vehicles and home from break-ins and theft, and to memorialize potential evidence for use in court proceedings and zoning board hearings. But these goals do not outweigh the Serranos' right to privacy and, tellingly, can be accomplished in other ways with no privacy intrusions. [Note 30] Speeding on the driveway is addressed by the speed bumps. House and vehicle security are addressed, and in fact better addressed, by pointing the cameras at the Bignamis' doors, windows, and vehicles themselves, not the driveway. And there should be either minimal future need, or no need at all, for evidence regarding driveway use. The judgment in this case, and the specific orders it enters, are designed be self-executing with no need for monitoring, thus ensuring that no future legitimate issues will occur with driveway use.

In short, the Bignamis' reasons for conducting video surveillance of the shared driveway are far outweighed by its invasion of the Serranos' privacy rights -- rights that are inherent in the express easement the Serrano property was granted. "When an easement or other property right is created, every right necessary for its enjoyment is included by implication." Sullivan, 287 Mass. at 267. This surveillance of the driveway causes the Serranos to avoid, limit, or dread the use of their express easement rights and is thus unreasonable and fundamentally inconsistent with the existence of the easement. It is thus prohibited. [Note 31]

MPM Builders Relocation of the Driveway

Neither the Bignamis nor the Serranos are particularly happy with the current location of the driveway. The Serranos would prefer to have a second driveway created over the Bignami property, located on the other (eastern) side of the Bignamis' house and serving just the Serrano lot. But that would require the consent of the Bignamis and is not going to happen. [Note 32] If the Serranos can only have the shared driveway (and that is all they are entitled to), they would like it to be widened so that two cars can pass. But that too is a non-starter. Their easement right is to the driveway, as is, and they have no right to demand that it be relocated or widened. See Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 176, 179 (1998) (with respect to an easement created by a conveyance, "the extent of the easement is fixed by the conveyance"; "judge's enlargement of the linear extent of the easement was unwarrantable, given the clarity of the instruments creating the easement.") (internal citations and quotations omitted). [Note 33] If there is to be any re-location of the shared driveway, it is solely at the Bignamis' option since they are the owners of the land over which it runs. See MPM Builders, 442 Mass. at 90, n.4 (easement holder may not unilaterally relocate an easement), 91- 92 (servient estate may relocate easement without easement holder's assent so long as purpose for which easement was granted is preserved, utility of easement is not significantly lessened, burden on use and enjoyment of easement by easement holder is not increased, and servient owner bears entire expense of the changes in the easement).

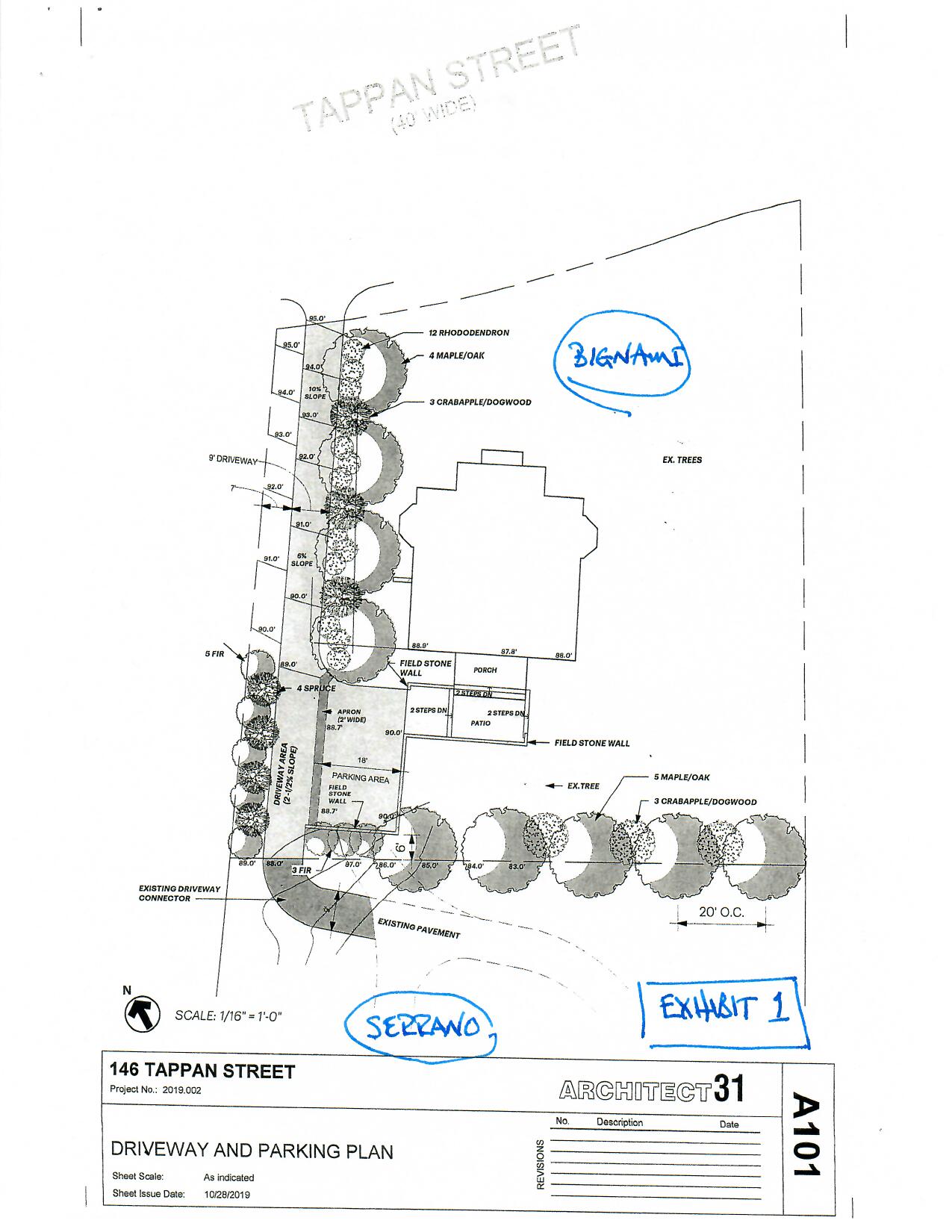

The Bignamis have proposed such a relocation as shown on the attached Ex. 1. [Note 34] The current driveway starts at Tappan Street, runs past the Bignami house, and then, once past the house and the Bignamis' two current parking spots on the eastern (house) side of the driveway, bends towards the Serrano lot. The Bignamis currently have a single parking space on the far side of the driveway on the western side of the bend. As shown on the relocation plan, the changes would be these. The existing asphalt driveway would be straightened, moved further away from the Bignamis' home so that it is closer to their western property line, and would now have a uniform width of 9'. [Note 35] The Exhibit shows the driveway as 7' back from the Bignamis' western lot line (approximately where the front section of the driveway is located today), but the Bignamis would prefer to locate it even further towards that western boundary so that it is only 5' back if they can do so as of right and without adversely affecting the neighbors' retaining wall on that side. This would put it further away from their house and enable them to enlarge their parking areas.

The differences between the existing driveway and the proposed relocated driveway are thus few, but they are key. As shown on Exhibit 1, the driveway would now be straight along its entire length, increasing the visibility both of the Serrano house and the driveway itself to drivers using it. It would be a uniform width. Its currently-varying topography would now be smoothed. The parking areas on the Bignami property would now be larger, raised, and level. Drainage control would be installed so that no run-off from the driveway goes onto the Serrano lot (the land slopes downhill from Tappan Street to the Serrano property). And by moving the driveway closer to the western lot line, the parking space that was formerly on the western side of the driveway would now be moved to the "house" side as part of an overall larger parking area. This would eliminate the safety concerns arising from crossing the present driveway to get to and from the car on the opposite side, and increase the overall space available for parking and turning vehicles around while staying entirely on the Bignami property. It is also consistent with the Bignamis' long-term plans to construct a garage on their property behind the proposed new parking area, further adding to their available parking.

The only material changes for the Serranos are (1) the increased visibility of their house from Tappan Street (something they themselves want), and (2) the need for a "connector" on their land to link their driveway to the relocated shared driveway. See Ex. 1 ("Existing Driveway Connector"). The Serranos indicated at trial that this is acceptable to them and, under MPM Builders, all the expense involved in the construction of the connector will be paid by the Bignamis.

For all of these reasons, I find and rule that the Bignamis may relocate the shared driveway as they have proposed, so long as it is properly constructed with appropriate drainage controls and they bear its entire expense. All of the MPM Builders criteria would be satisfied. See 442 Mass. at 90. The relocation preserves the purpose of the easement (pedestrian and vehicle access to the Serrano lot). Straightening the easement and making it a uniform 9' width increases its utility (it is now more visible and easier to plow), as does moving the Bignamis' parking space from the far side of the driveway to the house side which eliminates crossover conflicts. From the Serranos' perspective, it would be in a better location for them because it would increase the visibility of their house. The Serranos have no objection to the construction of the new connector on their property as long as it is properly done. And the Bignamis will be responsible for paying the entire expense of the relocation and connector. Thus, there will be no burden on the Serranos, only benefit, from the relocation.

The 40'-Wide Right of Way Easement, Never More Than for Pedestrian Use, Has Ended

The final issue in the case is the status of the 40'-wide right of way easement on the easterly side of the Bignami property. The Serranos contend that it exists and, moreover, can be developed by them for vehicular access to their lot. The Bignamis contend that it no longer exists at all. The Bignamis are correct.

The 40'-wide right of way, shown on the 1954 ANR plan that divided the former single lot into two, became an easement when, and only when, ownership of the two lots was separated. See Ritger, supra and the discussion in nn. 2 & 3, supra. It was an express easement, and thus governed by its express terms. See Sheftel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. at 176, 179. Those express terms were contained in the Alper to Faxon deed, recorded in the Norfolk Registry of Deeds in Book 3272, Page 547 (Jun. 24, 1954); "[t]his conveyance is subject to a 40-foot Right of Way over . . . Lot A [#146 - the Bignami property] . . . to be used for pedestrian traffic only. Provided, however, and it is specifically covenanted and agreed[,] that said 40-foot Right of Way shall not be used for any purpose by the owners or occupants . . . of said Lot B [#150 - the Serrano property] . . . so long as the present existing driveway [the shared driveway] . . . is available for all purposes for which driveways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline." (emphasis added). The 40'-wide right of way has never been developed or used as a way for any purpose at any time. Instead, access to the Serrano property has always exclusively been over the shared driveway, both pedestrian and vehicular.

The Town has had no problem with this. The Serranos obtained both a demolition permit (to take down the old garage) and a building permit (for their renovations) based on nothing more than the use of the shared driveway. That this was the only access to the lot was not secret. The Town's building inspectors paid many visits to the Serrano lot during demolition and renovation, and an occupancy permit was ultimately issued, with no issue of access ever raised. [Note 36]

The 40'-wide right of way easement ended on May 8, 1963 with the recording of the 1963 Agreement which gave the Serrano lot a permanent affirmative easement over the shared driveway. The shared driveway was thus now permanently available, which ended the 40'-wide easement by its terms ("said 40-foot Right of Way shall not be used for any purpose by the owners or occupants . . . of said Lot B [#150 - the Serrano property] . . . so long as the present existing driveway [the shared driveway] . . . is available for all purposes for which driveways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline.") (emphasis added). See Sheftel, supra (express easements governed by their terms). The 1963 Agreement was also an express abandonment of the 40'-wide easement. See 107 Manor Ave LLC v. Fontanella, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158 (2009) (internal citations omitted) (abandonment shown "by acts indicating an intention never again to make use of the easement in question"); Mello v. Town of Dighton, 32 Mass. L. Rep. 596, 599 (2015) (statement in deed showing intent never to make use of easement, and trustee's certificate expressly abandoning it, sufficient to show easement abandoned). The 40'-wide easement thus no longer exists and cannot be revived.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that: (1) the Bignamis have no right to park on the Serrano property or in any new garage the Serranos may construct, (2) the Bignamis have no right to drive onto the Serrano property for any purpose, (3) the Serranos continue to have an express easement to use the shared driveway to access their property, both for pedestrians and vehicles, (4) except for the school van that picks up the Bignamis' disabled child, no vehicle may pause or stop anywhere on the shared driveway for any purpose at any time, no matter how brief the pause or stop might be, (5) the Bignamis may install and maintain the speed calming measures described in this Decision on the shared driveway, (6) the Bignamis may install and maintain a fence between the properties, and also a fence, cinder blocks, or other barriers along the edges of the shared driveway so long as they are clearly marked (including with snow stakes in the winter) and do not encroach onto the shared driveway, (7) audio and video surveillance of the shared driveway is prohibited and permanently enjoined, (8) the Bignamis may relocate the shared driveway and construct a connector on the Serrano property in the manner and in the location described in this Decision so long as they do so properly, with adequate drainage control, and pay all costs associated with the relocation and connector, and (9) the 40-foot right of way easement over the Bignami lot for the benefit of the Serrano lot no longer exists for any purpose.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The shared driveway is on the opposite (western) side of the Bignami lot.

[Note 2] Its previous showing on the ANR plan did not make it an easement. As a matter of law, there can be no easement over land in common ownership that purports to benefit another part of that land. See Ritger v. Parker, 8 Cush. [62 Mass.] 145, 146 (1851). The reason for this is because there is no need for the easement's existence, as the owner has "the full and unlimited right and power to make any and every possible use of the land." Busalacchi v. McCabe, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 493 , 498 (2008), quoting Ritger, supra at 147. The actual easement in the 40' right of way did not arise until the conveyance of #150 out of common ownership, and its existence and scope was limited by the express terms of the grant in that deed. See n.3, below.

[Note 3] Deed, Alper to Faxon, Norfolk Registry of Deeds Book 3272, Page 547 (Jun. 24, 1954 ("This conveyance is subject to a 40-foot Right of Way over . . . Lot A [#146] . . . to be used for pedestrian traffic only. Provided, however, and it is specifically covenanted and agreed that said 40-foot Right of Way shall not be used for any purpose by the owners or occupants . . . of said Lot B [#150] . . . so long as the present existing driveway [the shared driveway] . . . is available for all purposes for which driveways are commonly used in the Town of Brookline.").

The significance of the use of the word "available" is addressed more fully below in the discussion of the complete extinguishment/abandonment of the 40' right of way easement in 1963.

[Note 4] There is no such garage at the present time.

[Note 5] The parties agree that the Serranos have no right to pause or stop in the shared driveway.

[Note 6] The term "rear lot" is used in the Brookline Zoning Bylaw as follows: "Where a lot is located to the rear of another lot or lots, it shall have feasible vehicular access to a street over a strip of land not part of any other lot and not less than 25 feet wide in S and SC Districts nor less than 20 feet in other districts. Such land may not be counted as more than 20 percent of the required lot area of such rear lot." Brookline Zoning Bylaw §5.14. The shared driveway and its use by the Serrano lot pre-date this provision, and is thus grandfathered.

[Note 7] See discussion below.

[Note 8] Deed, Alper to Faxon, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 3272, Page 547 (Jun. 24, 1954) (emphasis added).

[Note 9] Deed, Faxon to Barshak, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 3740, Page 69. (Jun. 19, 1959), conveying #150 "subject to, and with the benefit of, any restrictions, easements, or rights, of record, if any, so far as now in force and applicable." Any such change, of course, would have had to have been agreed by the owners of both #146 and #150.

[Note 10] Deed, Barshak to Moses, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 4055, Page 322 (Feb. 28, 1963), conveying #150 "subject to, and with the benefit of, any restrictions, easements, or rights, of record, if any, so far as now in force and applicable."

[Note 11] Agreement, Moses to Alper and Alper to Moses, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 4069, Page 226 (executed Mar. 14, 1963, recorded May 8, 1963).

[Note 12] Mrs. Alper apparently pre-deceased him.

[Note 13] Deed, Alper (executor) to Canner, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 10641, Page 663 (Aug. 11, 1994) ("This conveyance is subject to, and with the benefit of, all easements, agreements, restrictions, and rights of way, if any, of record and now in force and applicable.").

[Note 14] Deed, Canner to Register, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 14214, Page 175 (Jun. 14, 2000) ("Said premises are conveyed subject to and with the benefit of restrictions, easements and driveway rights of record, if any, as far as now in force and applicable.").

[Note 15] Deed, Register to Bignami, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 30182, Page 582 (Jul. 2, 2012) ("Said premises are conveyed subject to and together with any and all easements, restrictions, reservations, agreements and rights of way of record insofar as the same are now in force and applicable.").

[Note 16] Deed, Moses to Serrano, Norfolk Registry of Deeds, Book 34333, Page 11 (Jun. 14, 2016). The deed neither references nor mentions any easement rights.

[Note 17] These would be in the area shown on their recent site plans for the location of a proposed garage.

[Note 18] The first speed bump was installed in November 2017. The second was installed December 2017. The third and final speed bump was installed in Spring 2018.

[Note 19] The Bignamis have since turned-off the audio function, although the capability remains.

[Note 20] They were not, for example, pointed in the direction of the doors and windows to the Bignami house, which one would expect if their true purpose was security for the house.

[Note 21] Deeds are contracts, and the principles for interpreting them are the same for both.

[Note 22] The back wall of the old garage was the foundation wall of the Serrano house.

[Note 23] See the discussion of privacy rights in Massachusetts law, infra.

[Note 24] David and Victoria Register, who owned the property just before the Bignamis, also did "k-turns" backing out of their parking areas into the shared driveway and then exited onto Tappan Street without driving onto the Serrano lot or using it as a turn around.