Plaintiffs Michael W. Yogman and Elizabeth K. Ascher sued some of their Westport, Massachusetts neighbors in December 2019. Plaintiffs are husband and wife, and they own 666 River Road in Westport. They sought a decree declaring and "quieting" their rights in an easement called Ben's Point Lane, a partially built way that abuts the south side of 666 River Road. Ben's Point Lane runs west to east along the property. Plaintiffs want to use the Lane to reach the waters of the West Branch of the Westport River. The river is at the eastern (undeveloped) end of the Lane. Just south of where the Lane meets the river, the river enters Westport Harbor, an Atlantic inlet.

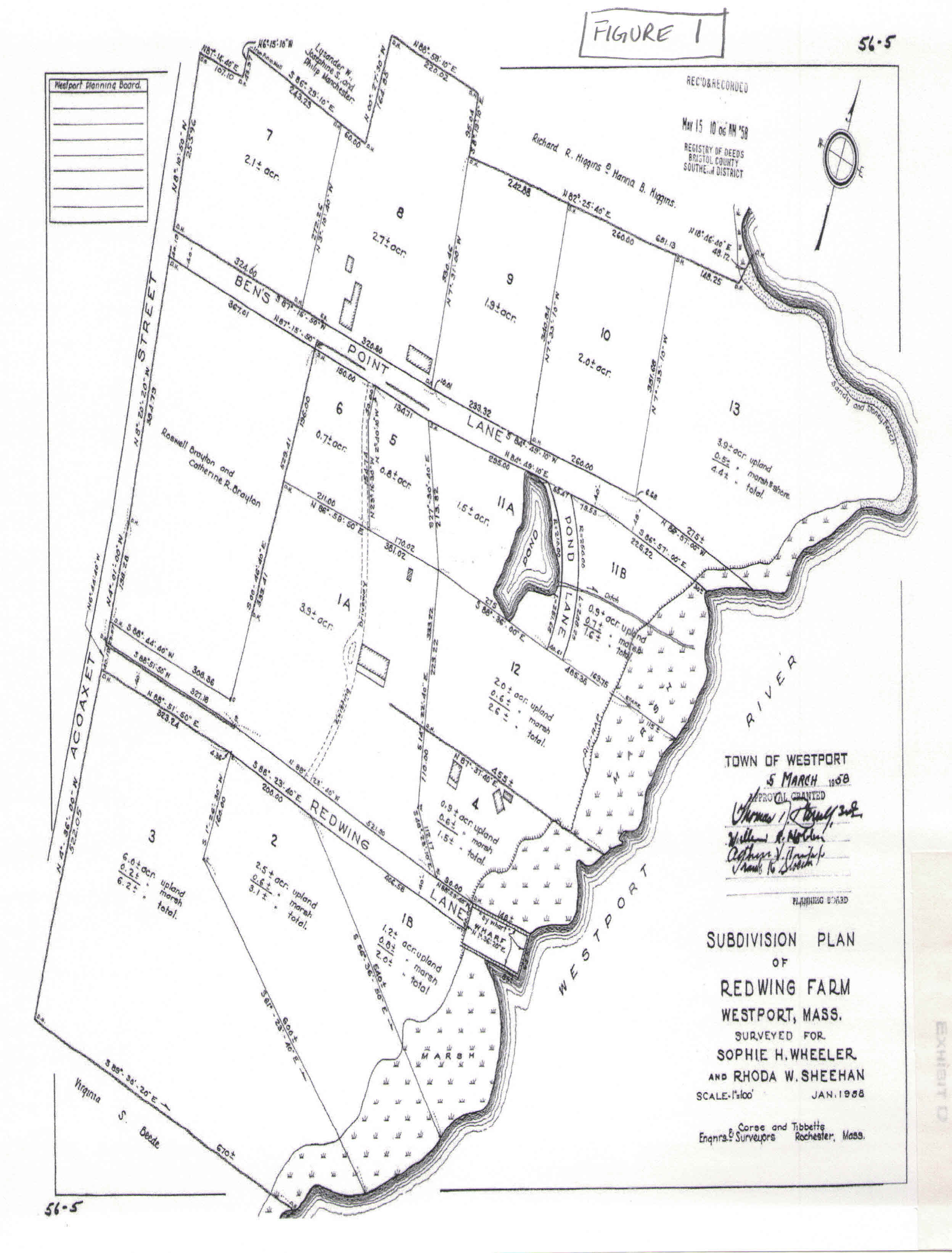

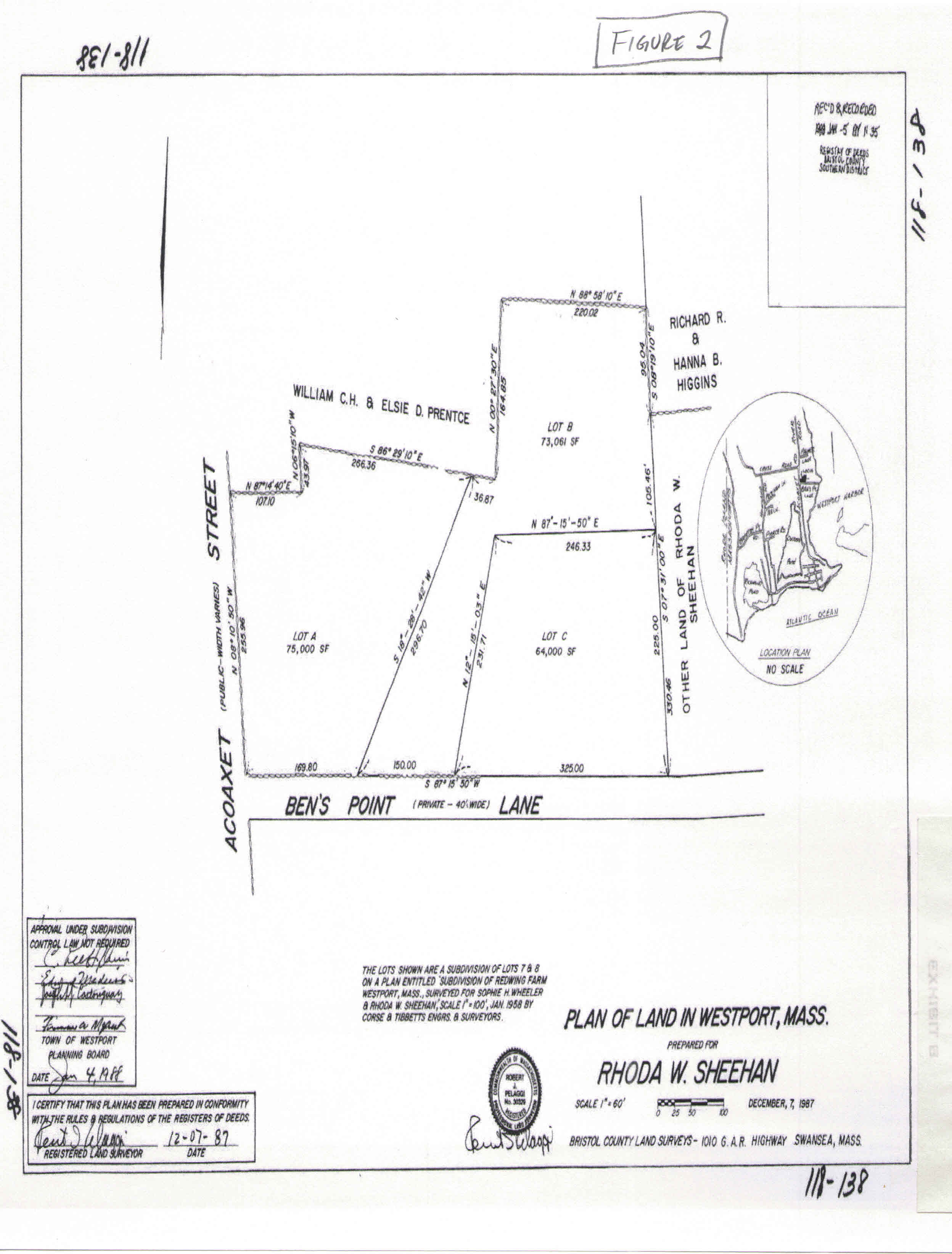

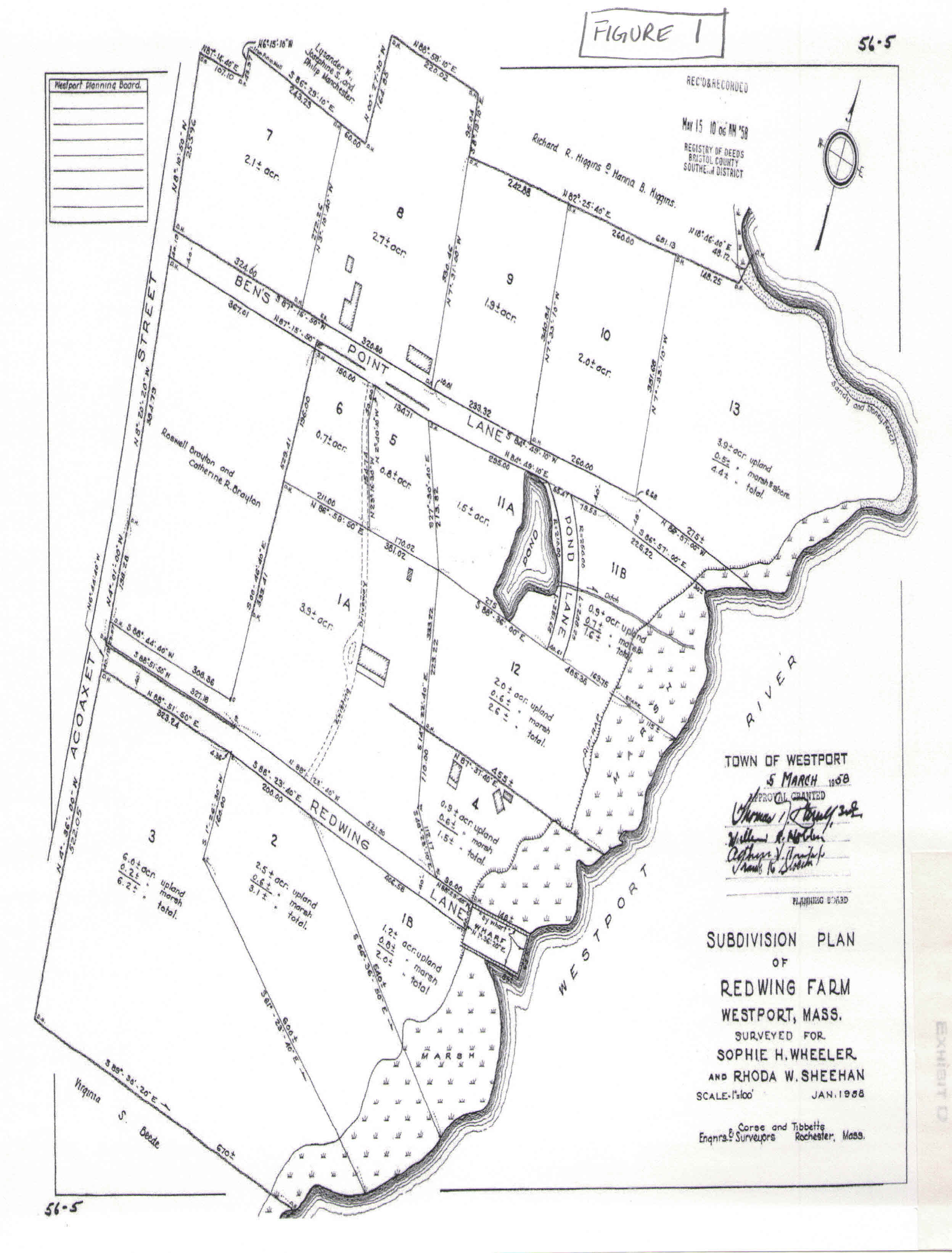

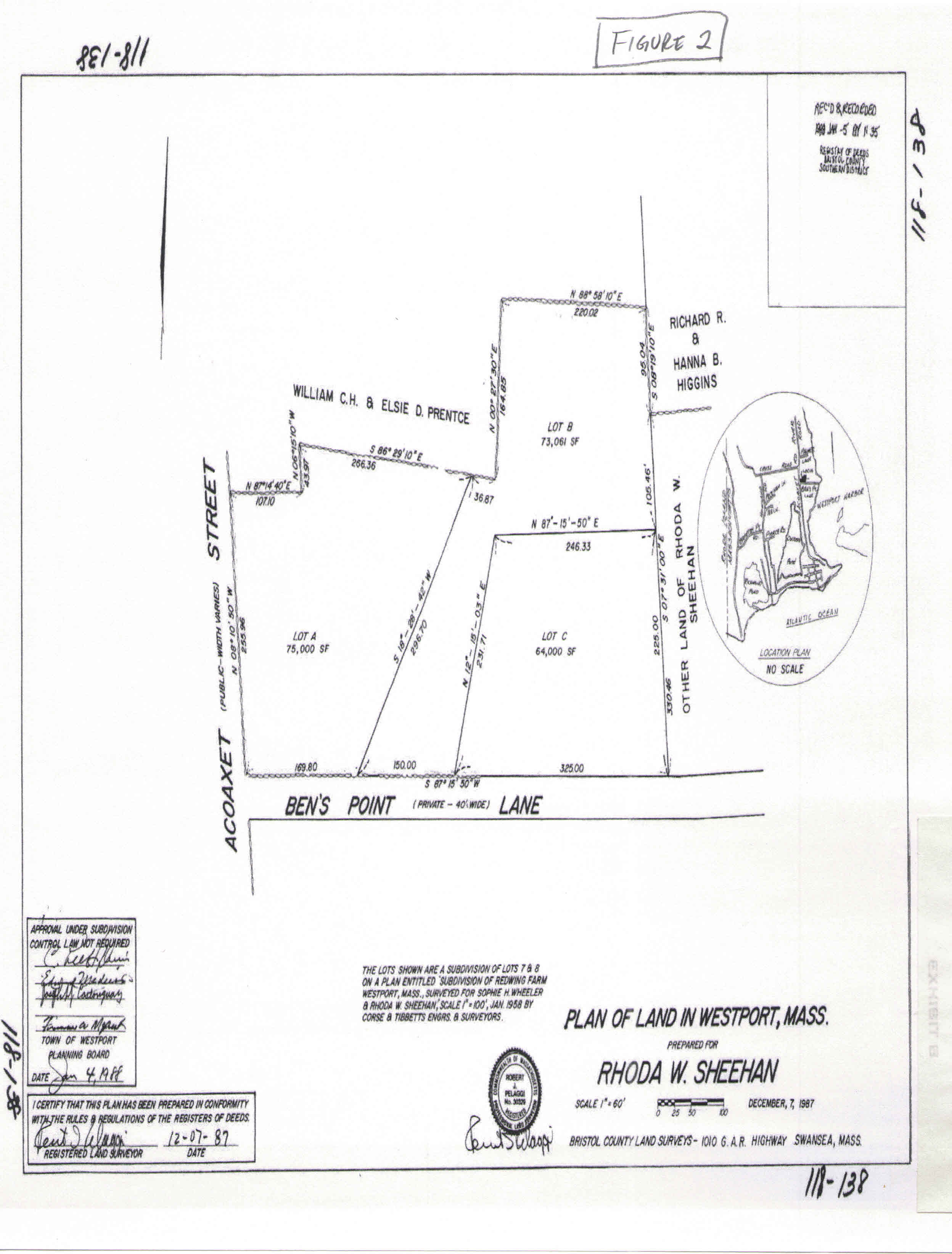

Pictures being worth a thousand words, the Court attaches to this Decision two figures. Figure 1 is the 1958 Subdivision Plan of Redwing Farm (the "1958 Subdivision"). What Figure 1 calls Acoaxet Street is now called River Road. When this Decision refers to a "Lot" by a number, the numbers are those that appear on the 1958 Subdivision. Figure 2 is a Plan of Land in Westport, Mass. Prepared for Rhoda W. Sheehan in 1987 (the "1987 Plan"). The 1987 Plan created within the 1958 Subdivision's Lots 7 and 8 three new parcels, Lots A, B, and C. When this Decision refers to a "Lot" by a letter, the letters are those that appear on the 1987 Plan. Plaintiffs' 666 River Road parcel is the 1987 Plan's Lot C.

Plaintiffs' suit names four defendants, but one can arrange them into two groups. Defendants James L. Rathmann and Anne F. Noonan (also husband and wife) are in one group. They own 682 River Road. Three parcels, Lots 5, 11A and 11B, comprise 682 River Road. Plaintiffs correctly allege in their complaint that Rathmann and Noonan don't own any of the fee beneath Ben's Point Lane, even though Lots 5, 11A and 11B abut the Lane. That's because in 1958, by written agreement (the "1958 Agreement"), Rathmann and Noonan's predecessor in title, Sophie H. Wheeler, conveyed to Rhoda W. Sheehan (she of the 1958 Subdivision) all of Wheeler's "right, title and interest . . . in and to the land shown on [the 1958 Subdivision] lying north of the south line of . . . Ben's Point Lane . . . ."

Early in this case, Mr. Rathmann and Ms. Noonan determined that they can neither grant to Plaintiffs rights to use Ben's Point Lane nor lawfully block Plaintiffs' use of the Lane. Thus, in late April 2020, Rathmann and Noonan agreed to abide by the outcome of this suit. That left unresolved Plaintiffs' claims against the other group of defendants in this case, Marion S. Vendituoli and Eileen W. Sheehan. They are the trustees of the RWS Family Holding Trust (the "RWS Trustees"). (The Court suspects that the "RWS" in the Trust's name comes from Rhoda W. Sheehan, but on the record before this Court, that's just a guess - a hunch that has no bearing on the outcome of this case.) The RWS Trustees own Lots 9, 10, and 13. And unlike Rathmann and Noonan's Lots 5, 11A and 11B, by virtue of the Derelict Fee Statute, M.G.L. c. 183, § 58, and the 1958 Agreement, the owners of Lots 9, 10, and 13 also own the fee beneath Ben's Point Lane that immediately abuts those Lots. [Note 1] Plaintiffs would cross that fee if they ever tried to use the Lane to reach the Westport River. The RWS Trustees have counterclaimed against Plaintiffs, insisting that Plaintiffs have no rights to cross Lots 9, 10 or 13.

Plaintiffs and the RWS Trustees have moved and cross-moved for summary judgment regarding Plaintiffs' easement rights. The facts set forth above (but not the Court's hunch) are undisputed. Based on those facts, the Court concludes that the RWS Trustees are right: Plaintiffs don't have the right to use Ben's Point Lane to reach the Westport River.

The additional pertinent undisputed facts are these. In the 1958 Agreement, in exchange for Sophie H. Wheeler ceding whatever rights she had in Ben's Point Lane, Rhoda W. Sheehan granted to Wheeler, for the benefit of certain lots south of the Lane (including the Rathmann/Noonan lots), various easement rights. The chief rights pertaining to the Lane that Sheehan granted to Lot 5 (one of the three Rathmann/Noonan lots) are found in paragraph 4 of the 1958 Agreement. That paragraph reads in pertinent part (emphasis added):

Rhoda W. Sheehan hereby grants to Sophie H. Wheeler as appurtenant to Lot No. 5 the right in common with said Rhoda W. Sheehan, her heirs and assigns, to pass and repass on foot or by vehicle over said Ben's Point Lane between the east line of Acoaxet Street and the east line of Lot No. 5 . . . .

The chief rights in the Lane affecting the two other Rathmann/Noonan lots, Lots 11A and 11B, are found in paragraph 3 of the 1958 Agreement (emphasis added):

Rhoda W. Sheehan hereby grants to Sophie H. Wheeler as appurtenant to Lots Nos. 11A, 11B, 12 and 4, the right in common with said Rhoda W. Sheehan, her heirs and assigns, to pass and repass on foot or by vehicle over said Ben's Point Lane between the east line of Acoaxet Street and the east line of Pond Lane. . . . No right is hereby granted over Ben's Point Lane east of Pond Lane.

From 1958 to 1985, Rhoda W. Sheehan owned Ben's Point Lane and every parcel on Figure 1 that abuts the north side of the Lane (to wit, Lots 7, 8, 9, 10, and 13). In 1985, she decided to sell Lot 13 - the one lot abutting the Westport River, and the one farthest from Acoaxet/River Street -- to a trust of which she was the trustee, the Bens [sic] Point Realty Trust (the "BPRT").

Ms. Sheehan's 1985 deed conveying Lot 13 (the "1985 Deed") created something of a template for two later conveyances by Sheehan to the BPRT. First, the 1985 Deed describes Lot 13 as bounded "Southerly by Ben's Point Lane Two Hundred Seventy-five (275) feet, more or less. . . ." Since Sheehan still owned Lots 7, 8, 9, and 10, and since all four lots are on the same side of the Lane as Lot 13, by operation of the Derelict Fee Statute, Sheehan conveyed to BPRT only the 275 feet of the Lane that abuts Lot 13. Second, the 1985 Deed identifies Lot 13 as being "Lot 13" on the 1958 Subdivision. Third, the only thing the 1985 Deed says about the use of the Lane is this: the 1985 Deed states it is conveying Lot 13 "[t]ogether with the right to use Ben's Point Lane for ingress and egress from Acoaxet Street along with others who are entitled to use the same." (Emphasis added.) Last, apart from its mention that "others" are entitled to use the Lane, the 1985 Deed doesn't state that Rhoda W. Sheehan or her successors in interest have or reserve the right to use the section of the Lane that abuts Lot 13.

Rhoda W. Sheehan's next conveyance of a Ben's Point Lane lot came in 1986, when she transferred to BPRT Lot 10, the lot that abuts the west side of Lot 13. Like the 1985 Deed, the 1986 deed conveying to BPRT Lot 10 (the "1986 Deed") describes Lot 10 as being bounded "Southerly by Ben's Point Lane Two Hundred Sixty (260) feet . . . ." As Sheehan still owned Lots 7, 8, and 9 on the same side of the Lane, by operation of the Derelict Fee Statute, the 1986 Deed conveyed to BPRT the 260 feet of the Lane that abuts Lot 10. And like the 1985 Deed, the 1986 Deed (a) identifies Lot 10 by reference to the 1958 Subdivision, (b) conveys to the owner of Lot 10 "the right to use Ben's Point Lane for ingress and egress from Acoaxet Street along with others who are entitled to use the same," and (c) is silent as to the particular rights of Sheehan and her successors in interest to use the section of the Lane that abuts Lot 10.

In 1987, Rhoda W. Sheehan received approval of the 1987 Plan. That Plan combined her Lots 7 and 8 as shown on the 1958 Subdivision and created three new parcels, Lots A, B, and C. (There'll be more discussion of the 1987 Plan later in this Decision.) Lot C was the site of Sheehan's home. In 1988, Sheehan conveyed Lot B by deed (the "1988 Deed") to her son Stafford Sheehan and his wife, Karen C. Sheehan. (The 1988 Deed is recorded at the Bristol South District Registry of Deeds in Book 2107, Page 30. Later in 1988, a corrective deed was recorded in Book 2137, Page 133. Unless noted, the latter deed didn't change anything in the 1988 Deed that matters to this case.)

The 1988 Deed doesn't follow the template of the 1985 and 1986 Deeds. For example, the corrected 1988 Deed describes the southern boundary of Lot B as "running N 87° 15' 50" E by the northerly line of Ben's Point Lane, One Hundred Fifty (150) feet . . . ." (Emphasis added.) The 1985 and 1986 Deeds describe the southern boundary as simply "by" the Lane. Usually that's a difference that makes no difference under the Derelict Fee Statute: for purposes of the Statute, granting something by the "line" of a way is equivalent to granting something by the way itself. See Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 804-805 (2003). As of the 1988 Deed, Rhoda W. Sheehan still owned Lots A, C, and 9, all of which were (and are) on the same side of Ben's Point Lane as Lot B. Therefore, pursuant to the Derelict Fee Statute, the 1988 Deed is presumed to have conveyed to Stafford and Karen Sheehan the 150 feet of the Lane that abuts Lot B.

The 1988 Deed's other material differences from the 1985 and 1986 Deeds are these: first, the 1988 Deed doesn't describe Lot B by reference to the 1958 Subdivision. In fact, the 1988 Deed doesn't mention the 1958 Subdivision at all. Instead, the 1988 Deed states that the 1987 Plan describes Lot B. Second, the 1988 Deed contains no language that grants rights in Ben's Point Lane either west or east of Lot B. Instead, the 1988 Deed grants

an easement, with all rights, privileges, and appurtenances thereto, to pass and repass for the installation of public utility lines, along a way twenty (20) feet in width running northeasterly from the northerly line of Ben's Point Lane inside the westerly boundary of Lot C on the [1987 Plan], for a distance of Two Hundred Thirty-one and 71/100 feet (231.71') to the northerly boundary of . . . Lot C.

But one thing is common among the 1985, 1986 and 1988 Deeds: none of them specifically describes what, if any, rights Rhoda W. Sheehan or her successors in interest reserved in that part of Ben's Point Lane that abuts each of the lots those Deeds conveyed.

In 1989, Rhoda W. Sheehan conveyed another of her Ben's Point Lane parcels, Lot 9. She conveyed it to then-owner of Lots 10 and 13, BPRT. Like the 1985 and 1986 Deeds, the deed conveying Lot 9 (the "1989 Deed") describes Lot 9 as "Southerly by Ben's Point Lane Two Hundred Thirty-Three and 32/100 (233.32) feet . . ." As of the 1989 Deed, Rhoda W. Sheehan still owned Lots A and C. Thus, under the Derelict Fee Statute, the 1989 Deed conveyed to BPRT the fee beneath the 232.32 feet of Ben's Point Lane that abuts Lot 9. And the 1989 Deed followed the template of the 1985 and 1986 Deeds in other ways: like those deeds, the 1989 Deed describes Lot 9 by reference to the 1958 Subdivision (and doesn't mention the 1987 Plan). Like the 1985 and 1986 Deeds, the 1989 Deed states that the BPRT is receiving Lot 9 "[t]ogether with the right to use Ben's Point Lane for ingress and egress from Acoaxet Street along with others who are entitled to use the same." And like the 1985 and 1986 Deeds, the 1989 Deed doesn't say anything about the particular rights of Rhoda W. Sheehan or her successors in interest to use the part of Ben's Point Lane that abutted the newly conveyed lot (this time, Lot 9).

We arrive at the last transfer at issue in this suit. Rhoda W. Sheehan died in 1997. In 1999, by virtue of a power of sale in her will, her son Philip Sheehan sold her residential parcel, Lot C, to Alice Turner. Plaintiffs are Turner's successors in interest to Lot C. The deed for the 1999 sale (the "1999 Deed") doesn't contain a metes-and-bounds description of Lot C. Instead, it refers to Lot C simply as "the land in Westport . . . , with the buildings thereon, being shown as Lot C on [the 1987 Plan]." The 1999 Deed states that Lot C is subject to three easements: the easement described in the 1988 Deed, another easement granted to two utility companies, and a septic-system easement granted to Stafford and Karen Sheehan. The 1999 Deed then states that its grant of Lot C is "[t]ogether with the right to use Ben's Point Lane as shown on said plan in common with others having rights in said Lane, for all purposes for which public streets are used in the Town of Westport." (Emphasis added.)

The 1999 Deed left Rhoda W. Sheehan's estate with only one Ben's Point Lane parcel, Lot A. The estate has since sold Lot A.

Those asserting easement rights (here, Plaintiffs) have the burden of proving that an easement exists. See Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 757 (1945). Plaintiffs rest their claim to use the entirety of Ben's Point Lane on two easement theories, easement by grant (the purported grant being included in the 1999 Deed) and easement by estoppel. The Court examines each theory in turn.

Easement by grant. Whether the 1999 Deed grants Plaintiffs the right to use the entirety of Ben's Point Lane "'must be found in a presumed intention of the parties'" to that deed, "'to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable.'" Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 344 (1967), quoting Dale v. Bedal, 305 Mass. 102 , 103 (1940).

When the language of the applicable instruments is "clear and explicit, and without ambiguity, there is no room for construction, or for the admission of parol evidence, to prove that the parties intended something different." "[T]he words themselves remain the most important evidence of intention," but those words may be construed in light of the attendant circumstances, and "the objective circumstances to which [the words refer]." "[T]he grant or reservation [creating an easement] 'must be construed with reference to all its terms and the then existing conditions as far as they are illuminating.'"

Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 25-26 (2006) (citations omitted; brackets and emphases in Hamouda), quoting Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. (7 Cush.) 526, 528 (1851); Robert Indus., Inc. v. Spence, 362 Mass. 751 , 755 (1973); McLaughlin v. Selectmen of Amherst, 422 Mass. 359 , 364 (1996); and Mugar v. Massachusetts Bay Transp. Authy., 28 Mass. App. Ct. 443 , 444 (1990).

Based on the language of the 1999 Deed and the undisputed attendant circumstances, the Court holds that the 1999 Deed does not grant Plaintiffs the right to use the entirety of Ben's Point Lane. First and foremost, the 1999 Deed states that it is granting "the right to use Ben's Point Lane as shown on said plan in common with others having rights in said Lane, for all purposes for which public streets are used in the Town of Westport." (Emphasis added.) The "surveyed" portion of the 1987 Plan shows only the western end of Ben's Point Lane, and not the part that runs to the Westport River.

Plaintiffs respond that the 1987 Plan presents two depictions of Ben's Point Lane. They concede that the "surveyed" portion of the Plan, the part of the Plan that's most apparent to any reader of the Plan, shows only the Lane's western end. But look closer at the 1987 Plan: in an oval inset, there's a "Location Plan." The "Location Plan" shows the entirety of the Lane, including the unbuilt stretch that goes to the Westport River. The 1987 Plan also says that "[t]he lots shown are a subdivision of Lots 7 & 8 on a plan entitled 'Subdivision of Redwing Farm Westport, Mass., Surveyed for Sophie H. Wheeler & Rhoda W. Sheehan,' Scale 1" = 100', Jan. 1958 by Corse & Tibbetts Engrs. & Surveyors" - that is, the 1958 Subdivision. Plaintiffs argue that these two facts prove that when the 1999 Deed talks of the Lane "as shown on said plan," the 1999 Deed means the entire Lane as laid out in 1958.

The Court holds that the 1999 Deed's reference to the Lane "as shown on said plan" is a reference to the "surveyed" portion of the 1987 Plan, the part of the plan that underwent the rigors of a professional survey. One case and five facts buttress the Court's interpretation:

* Darman v. Dunderdale, 362 Mass. 633 , 638 (1972), holds that when a grantor's deed refers to a recorded Plan No. 2, but Plan No. 2 bears a legend reference to a recorded Plan No. 1, a party has to provide additional evidence that the grantor intended to include in his or her deed easements over the ways shown on Plan No. 1: a chain of plan references doesn't suffice to prove the grantor intended to grant anything with respect to Plan No. 1. So the 1987 Plan's reference to the 1958 Subdivision, standing alone, doesn't win the day for Plaintiffs.

* By the time of the 1999 Deed, Rhoda W. Sheehan had conveyed to BPRT the sections of the Lane that lie along Lots 9, 10, and 13, without expressly reserving (in so many words) any rights to herself or her successors in interest in the sections of the Lane that lie along Lots 9, 10, and 13. Sheehan's estate thus did not have power to grant easements over those sections of the Lane. See also Knapp v. Reynolds, 326 Mass. 737 , 740-741 (1951) (one who no longer owns a fee may not create by later deeds easements over that fee).

* By contrast, in 1999, Sheehan's estate still owned the fee in the Lane that abuts Lots A and C. Thus, consistent with the RWS Trustees' interpretation of the 1999 Deed, Sheehan's estate could have granted via the 1999 Deed rights to use the Lane as it abuts Lots A and C. Those sections of the Lane appear on the more apparent "surveyed" portion of the 1987 Plan.

* In every conveyance prior to 1999, Rhoda W. Sheehan expressly granted only such rights in the Lane that the grantee needed for ingress and egress from Acoaxet/River Street. None of her pre-1999 grants expressly granted anyone the right to use the Lane to reach the Westport River.

* At the time of the 1999 Deed, the eastern end of the Lane hadn't been built - a fact that, while not dispositive of Sheehan's ability to grant an easement in the unbuilt portions of the Lane, see Hickey v. Pathways Ass'n, Inc., 472 Mass. 735 , 758 n.30 (2015), nevertheless sheds light on the intent of the parties to the 1999 Deed. See Labounty, 352 Mass. at 344 (physical condition of the premises is relevant to the analysis of whether the parties intended to grant an easement over the premises).

* Finally, the western end of the Lane, the end that the "surveyed" portion of the 1987 Plan depicts, had served since the 1950s (and still serves today) an important purpose: it provides access to a public way, Acoaxet/River Street. The far eastern end of the Lane has never served that purpose.

Plaintiffs challenge the conclusion that, via the 1985, 1986, and 1989 Deeds, Rhoda W. Sheehan deeded away her rights to grant easements over the eastern end of Ben's Point Lane. Plaintiffs argue that Sheehan implicitly reserved in those Deeds the right to grant easements in the Lane: after all, all three deeds state that BPRT's easement rights in the Lane are shared "with others who are entitled to use the same"; those "others" could have included Rhoda W. Sheehan herself. But Massachusetts law disfavors reading into a deed rights that run in favor of the grantor, if the same deed gives express easements to the grantee. See Krinsky v. Hoffman, 326 Mass. 683 , 685, 687-688 (1951) (deed that was "subject to all the rights, restrictions, stipulations and agreements . . . so far as now in force and applicable" did not identify grantor as having such rights; grantor should have included an express reservation in the deed to make that happen). Moreover, as a matter of grammar, the words "with others who are entitled to use the same" modifies the phrase that immediately precedes it, "the right to use Ben's Point Lane for ingress and egress from Acoaxet Street . . . ." (Emphasis added.) At best, Plaintiffs' suggested reservation of rights by Rhoda W. Sheehan to grant additional easements in the Lane as it crosses Lots 9, 10, and 13 would be limited to the purpose of furnishing later grantees ingress and egress from Acoaxet/River Street.

Plaintiffs argue that, if one can't find in all of Rhoda W. Sheehan's Ben's Point Lane conveyances an implied reservation of her right to use the Lane for its entire length, then her 1988 Deed, which conveyed Lot B, would have landlocked Lot C, the parcel on which Sheehan lived in 1988. If the 1988 Deed is the only thing that bears on Lot C's right to use the Lane from Lot C to Acoaxet/River Street, Plaintiffs might be right about the consequences of the Court's reading of the 1985, 1986, and 1989 Deeds. (If all conveyances were the product of carefully drafted deeds, first-year law students wouldn't have the pleasure of learning about two common law lifelines for landlocked parcels, the doctrine of easement by implication and the doctrine of easement by necessity. See, for example, Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 104 (1933) (discussing easements by implication); Kitras v. Town of Aquinnah, 474 Mass. 132 , 139 (2016) (discussing easements by necessity).) But Plaintiffs offer no reason why what appears to be an exception among the Sheehan conveyances, the 1988 Deed, forces reading into the earlier 1985 and 1986 Deeds, as well as the nearly identical 1989 Deed - deeds that involved different parties, different circumstances and different sections of Ben's Point Lane relative to Lot C - a reservation of rights by Rhoda W. Sheehan to grant others easements to use the Lane to reach the Westport River. The Court thus holds that the 1999 Deed does not grant Plaintiffs an easement over the Lane as it crosses the RWS Trustees' properties.

Easement by estoppel. The Appeals Court has rejected "general estoppel principles" in determining whether an easement exists. See Blue View Const., Inc. v. Town of Franklin, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 345 , 355 (2007). Instead, the court has held

that an easement may be created by estoppel in two ways. First, when a grantor conveys land bounded by a street or way, he, and those claiming under him, are estopped to deny the existence of the street or way, and his grantee acquires rights in the entire length of the street or way as then laid out or clearly prescribed. Second, when a grantor conveys land situated on a street in accordance with a recorded plan that shows the street, the grantor, and those claiming under him, are estopped to deny the existence of the street for the distance as shown on the plan. Thus, in each of those instances, easements by estoppel arise by virtue of the conveyance made by the grantor to the grantee. "Both categories of cases deal with the rights of grantees or their successors in title against their grantors and their successors in title."

Id. at 355 (citations omitted), quoting Patel v. Planning Bd. of N. Andover, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 477 , 482 (1989).

Plaintiffs gain something from Blue View and Patel: the 1999 Deed refers to the 1987 Plan. Blue View and Patel are clear that that plan reference estops Plaintiffs' grantors - that is, Rhoda W. Sheehan's estate - and the estate's successors in interest from contesting the existence of Ben's Point Lane "for the distance as shown on the plan." Blue View, 70 Mass. App. Ct. at 355. But this raises again the question of which part of the 1987 Plan, the "surveyed" portion of the Plan or its oval inset? The Court concludes from the undisputed facts discussed earlier that Blue View and Patel's estoppel doctrines reach only the parts of Ben's Point Lane that appear on the "surveyed" portion of the 1987 Plan. [Note 2]

The Court thus won't estop the RWS Trustees from asserting that Plaintiffs lack the right to use Ben's Point Lane as it crosses the Trustees' properties. Instead, the Court will declare that the Plaintiffs lack such rights.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

MICHAEL W. YOGMAN and ELIZABETH K. ASCHER, Plaintiffs v. MARION S. VENDITUOLI and EILEEN W. SHEEHAN, as Trustees of RWS Family Holding Trust; JAMES L. RATHMANN and ANNE F. NOONAN, Defendants

MICHAEL W. YOGMAN and ELIZABETH K. ASCHER, Plaintiffs v. MARION S. VENDITUOLI and EILEEN W. SHEEHAN, as Trustees of RWS Family Holding Trust; JAMES L. RATHMANN and ANNE F. NOONAN, Defendants