Introduction

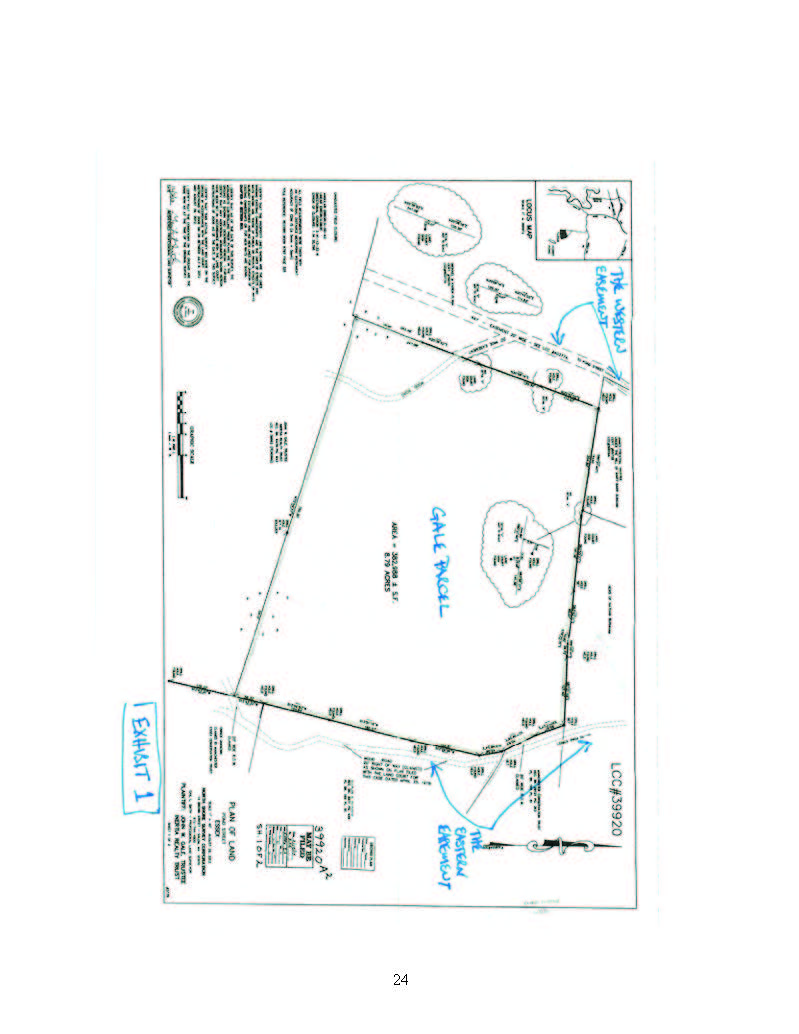

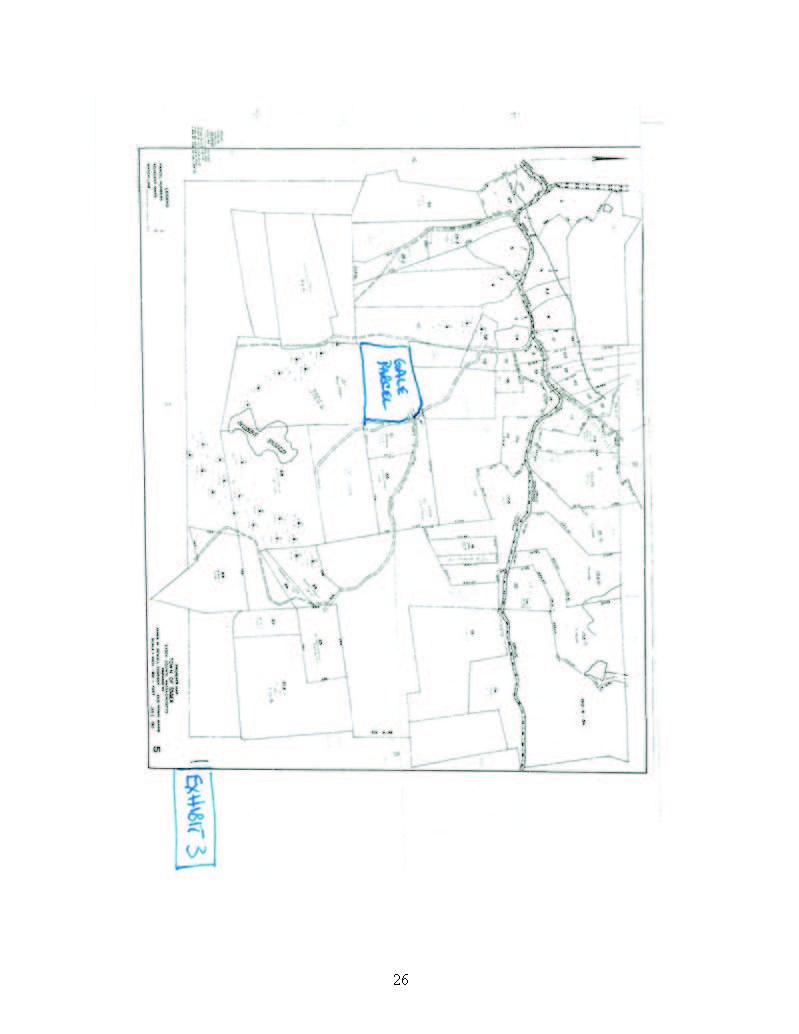

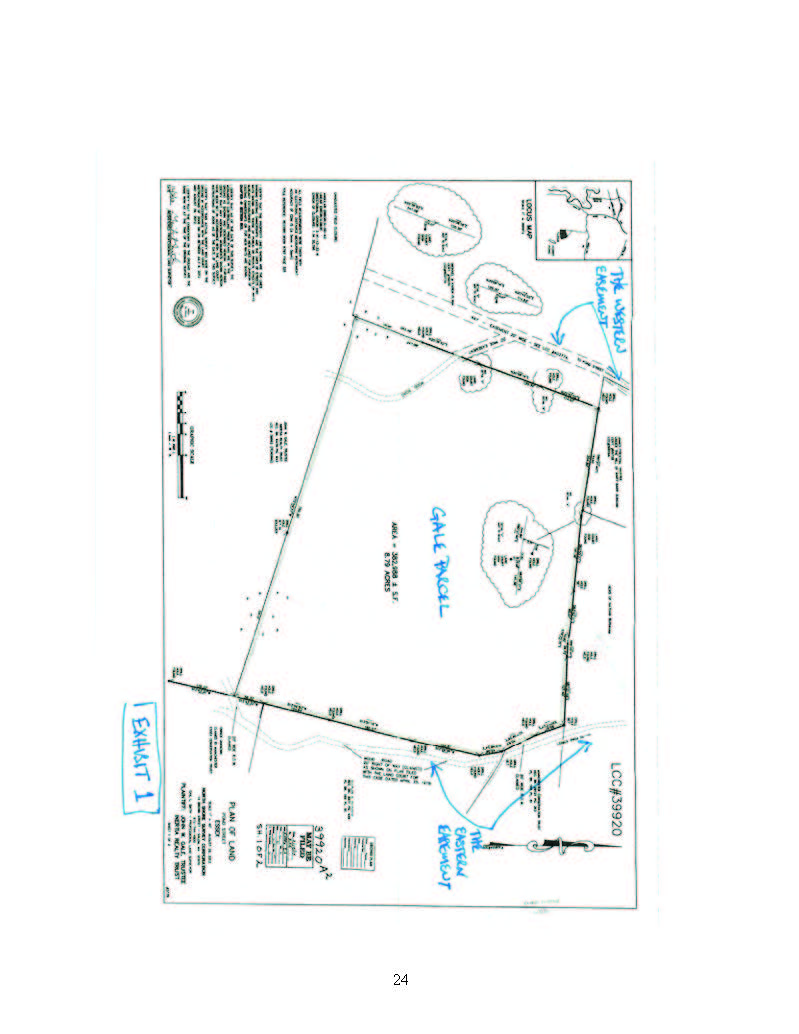

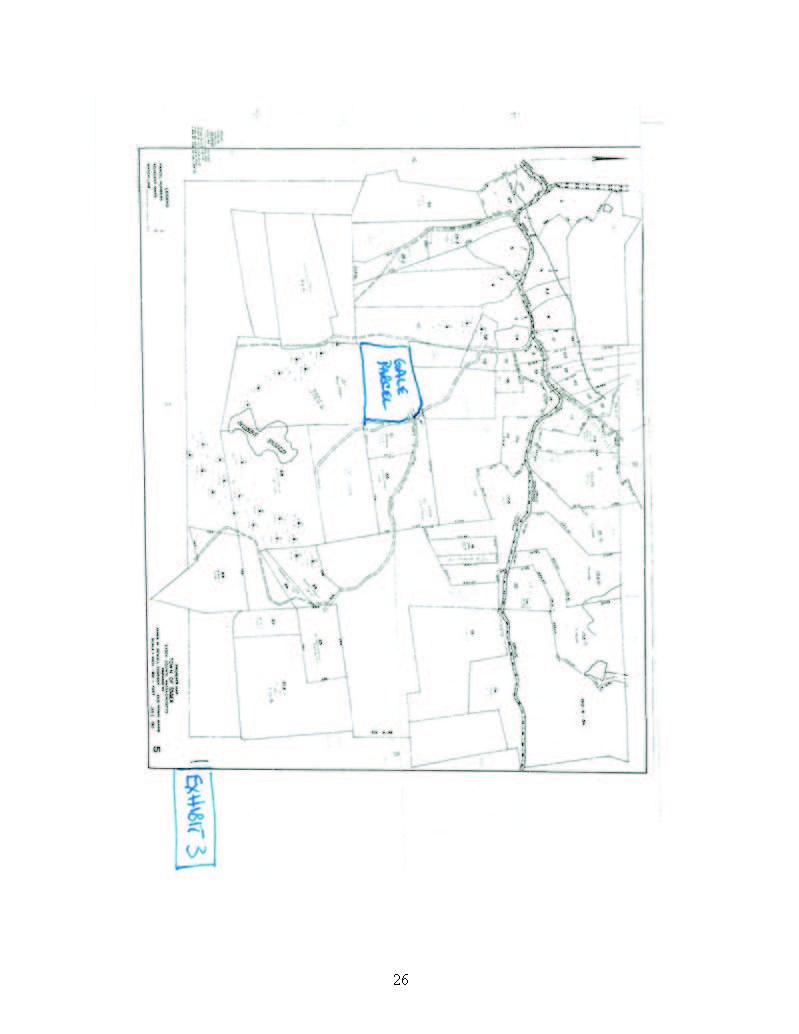

In this action, petitioner John Gale [Note 1] seeks to register title to an 8.79 acre parcel in Essex, the location and boundaries of which are shown on Sheet 1 of his proposed registration plan, a copy of which is attached as Ex. 1 (the "Gale parcel"). [Note 2] All abutters and other interested parties have been duly served and either agree to that request or, expressly or by default, do not oppose it. Moreover, independent of those agreements and defaults, the evidence shows that Mr. Gale has "good title [to the parcel] as alleged, and proper for registration." [Note 3], [Note 4] Subject to the final review of the title, I so find. [Note 5]

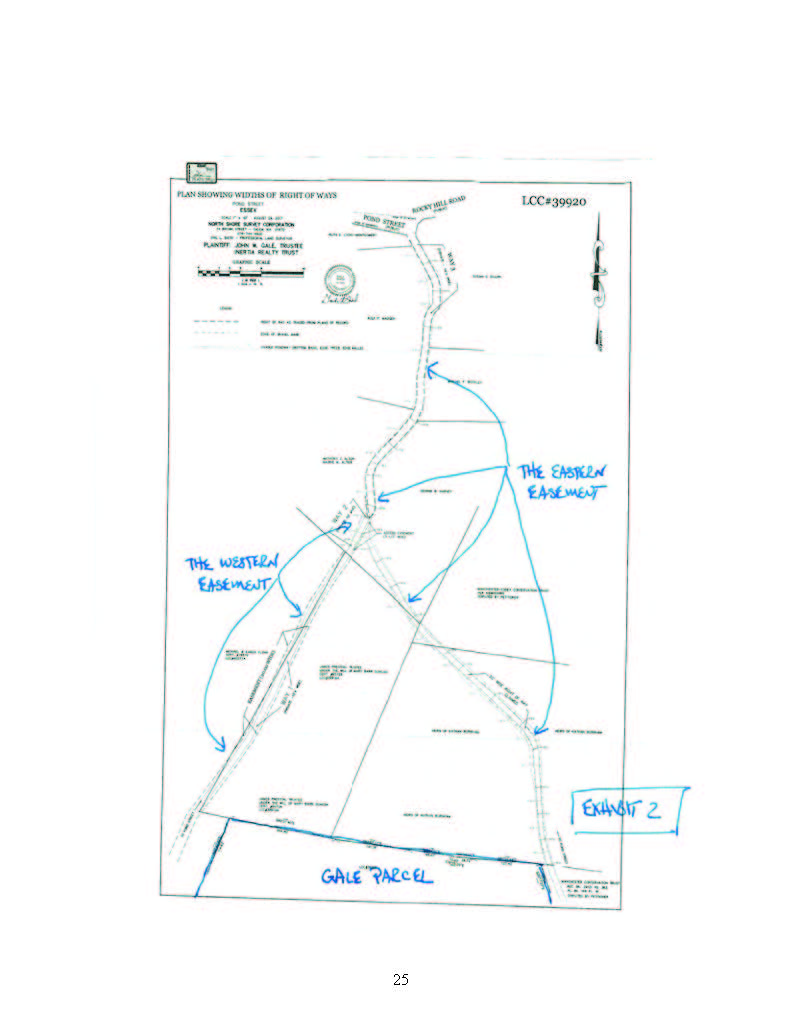

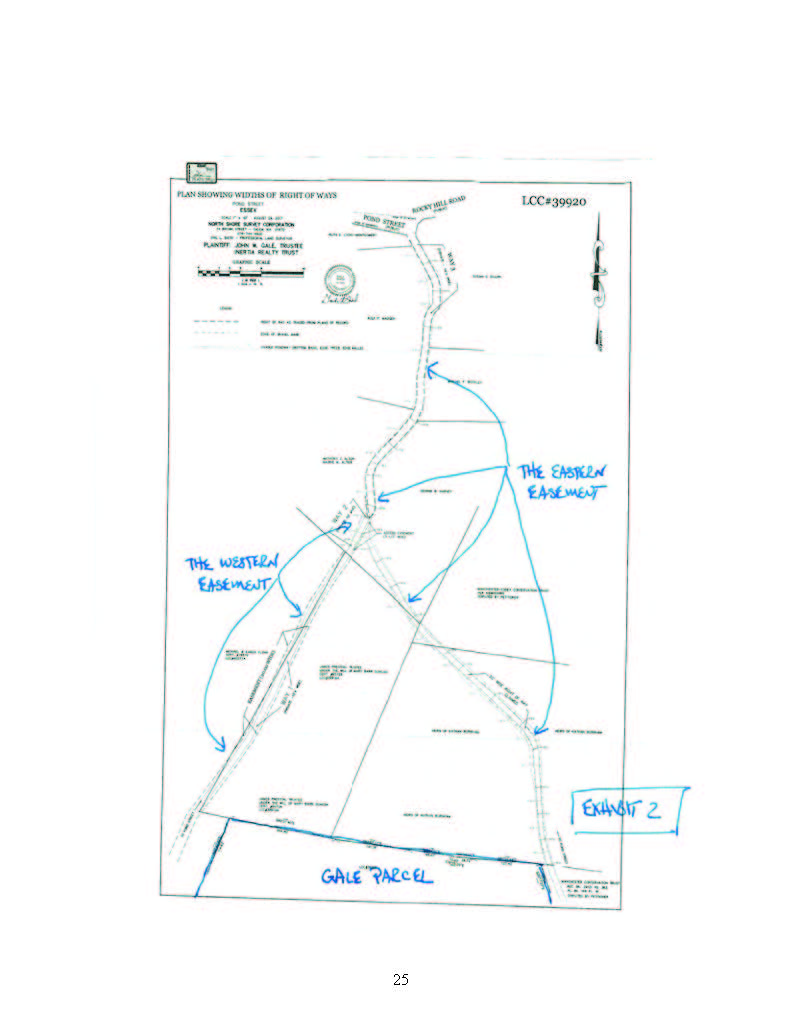

But more is also sought. Mr. Gale has plans to develop the parcel as homesites for his two daughters and, to do so, needs roadway access adequate for that purpose. He thus requests the additional declaration that his parcel has the benefit of two appurtenant easements, each, he claims, 20'-wide, one leading from Pond Street (a public road) to and along the east side of his parcel (the "eastern easement"), and the other branching off from the eastern easement at a point just north of his parcel and then leading to the parcel's west side (the "western easement"). These easements are shown on Ex. 2. Here again all abutters and other interested parties have been duly served, and again there has been either express assent or no opposition to this request, with one exception - the objections raised by respondent Manchester Essex Conservation Trust ("MECT"), which owns land on the opposite side of the eastern easement from the Gale parcel that is also accessed by that roadway. [Note 6]

MECT concedes the existence of the western easement and, with the exception of one small section (which it contends is narrower), does not oppose a declaration that it is 20'-wide along its entire length. It could hardly do otherwise since, with the exception of that section, Mr. Gale has an express 20'-wide easement from the underlying fee owners. Moreover, as a legal matter, MECT has no standing to raise an objection to any aspect of the western easement because none of that easement crosses its property or serves its land. That lack of standing, however, does not relieve Mr. Gale of the affirmative burden of proving his entitlement to a 20' width in the disputed section if he wants a judgment so holding. See Hermanson, supra. I thus address that issue below.

With respect to the eastern easement, MECT again concedes its existence. Again, it could hardly do otherwise since it uses that easement itself and has no greater rights than Mr. Gale to do so. But MECT contends that that easement is only prescriptive, that it is only 14' wide, and that it goes no further than the northeast corner of the Gale parcel, not (as Mr. Gale contends) also to his southeast corner. [Note 7] The difference between 14' and 20' is important for Mr. Gale because a 20'-wide access to Pond Street would allow the Gale parcel to be developed and anything less might limit, or perhaps entirely prevent, any such development. [Note 8] The western easement goes only as far as its intersection with the eastern easement, far short of Pond Street, and thus cannot provide the necessary 20'-wide access from Pond Street on its own. See Ex. 2. For development of the parcel, the eastern easement is the key one.

Mr. Gale contends that he is entitled to a 20'-width over the full length of the eastern easement and the disputed section of the western one even if they are only prescriptive. But his primary argument is that they are both express easements by grant from the Proprietors of the Town of Ipswich through their "Committee Appointed to Lay Out the Woodlands" (Mar. 9, 1710/1711) [Note 9] (hereafter, the "Roadway Grant"), and that that grant currently entitles him to a 20' width. MECT has stipulated that the Gale parcel is one of the "lotts" benefited by the Roadway Grant [Note 10] and, after review of the evidence, I concur and so find. But MECT disputes the current effect of that grant, particularly on the question of the width it allows.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. I also took a view. [Note 11] Based on the parties' stipulations, the witness testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, reliability, and appropriate weight of that evidence, my observations at the view, and the reasonable inferences I draw from this totality, I find and rule as follows.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

As noted above, Mr. Gale has good title, proper for registration, to the entirety of the Gale parcel (Ex. 1). This was proved by the evidence, [Note 12] and none of the respondents, all of whom have been duly and properly served, have raised any issues or objections to that title. I so find.

It is also undisputed, and was shown by the evidence, that the Gale parcel has the benefit of the western easement and, with the exception of the disputed section, that the western easement is 20'-wide by express grant from its underlying fee owners. I so find. The nature of the dispute regarding that section, and why the Gale parcel has the right to a 20' width there as well, is discussed below.

The eastern easement was the chief focus of the trial and, as previously noted, is the only one that MECT has standing to oppose. Mr. Gale contends that it is an express easement pursuant to the Roadway Grant, and that it is 20'-wide along its entire length. MECT contends that it is only prescriptive, and only 14'. Mr. Gale counters that, even if the easement is only prescriptive, his prescriptive rights entitle him to 20'.

I begin with the origin of the easement roadways, both east and west.

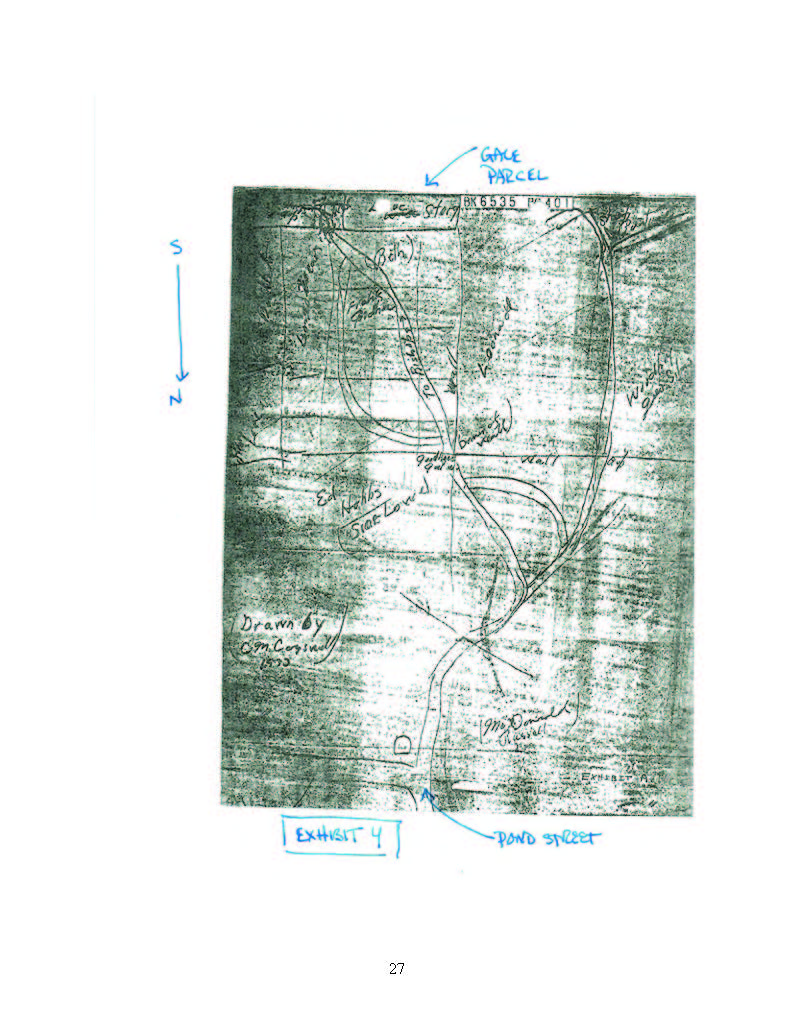

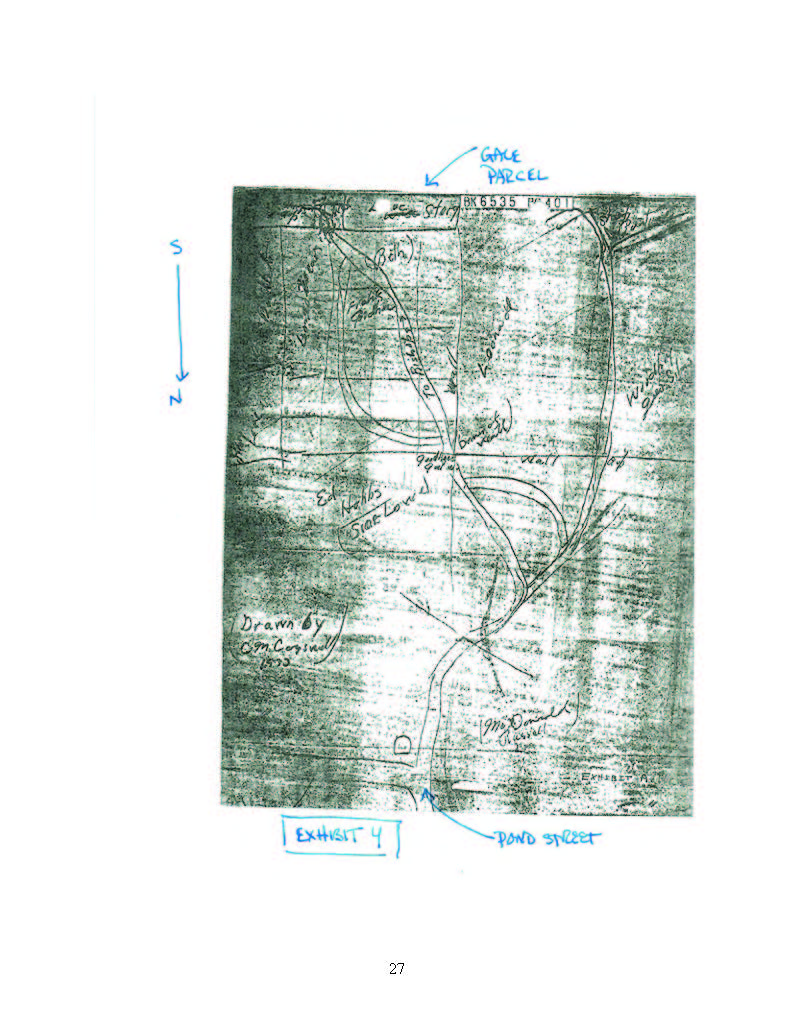

Both the eastern easement and the western easement are woodland roads, and both have existed for as long as anyone can remember. See, e.g., Ex. 3 (1968 plan showing the woodland roads in this area, including the eastern and western easements); the Affidavits of Hervey and Luther Burnham (included in the Land Court Title Examiner's Report, Trial Ex. 29) which detail their father's descriptions of the roads dating back to 1840 (his childhood) and their own personal observations dating back to 1910 (their childhood); the 1933 sketch attached to the Hervey Burnham affidavit that shows these and the other roads through the woodlands (a copy of which is attached as Ex. 4); and the various plans introduced into evidence at trial that show both of these roads and label them "Old Road to Manchester" or "Old Road." Both of the easement roadways were part of the Roadway Grant dated March 9, 1710/1711. [Note 13]

The background to the grant is a window into the history and early development of Massachusetts after the European settlement.

Essex did not become incorporated until 1819. Before that it was part of Ipswich (incorporated 1634) and called Chebacco Parish.

In its earliest Colonial times, Ipswich, like many parts of Massachusetts, was governed by "proprietors" whose meetings were the precursors to town meetings. "Proprietors" were groups of individuals to whom the governor and company of "Massachusetts Bay in New England" [Note 14] granted land as tenants in common, and which those individuals would then, by vote, divide among themselves as they deemed appropriate. They would often do so through appointed committees, which were charged to divide the land "among the freemen for the purposes of settlement, reserving such parts as might be deemed requisite for various public uses." See generally Attorney Gen. v. Tarr, 148 Mass. 309 , 311 (1889); Codman v. Winslow, 10 Mass. 146 , 15051 (1813).

In 1710, the Ipswich proprietors did exactly that, appointing a three-person committee "to lay out the woodlands and the lands accounted equivalent thereto . . . so that every proprietor may have his just due . . . when the lotts are drawn." The charge to that committee, and the division the committee decided upon, was as follows:$ [Note 15]

Subscribers [the individuals named below] being the Committee appointed to lay out the woodlands and the lands accounted equivalent thereto by vote of the proprietors may more at large appear - so we according to our best judgment divided those lands into lotts so that every proprietor may have his just due as well as the [surveying?] of the place would allow of: and all the several lotts are butted and bounded and the number of the lotts cut only bound marked which are all entered in the book, so that when the lotts are drawn, although it be woody and country land, we can easily show every man his lott. Having reserved all the highways and paths that are already made in all the lands laid out for the several proprietors to pass and repass as they shall have occasion; and where a way is wanting, we have reserved that privilege in general for the proprietors that they may pass and repass over each [ ?] lott as they may have occasion where it may be most convenient for them: with least prejudice to their neighbors['] lotts that they pass through; and if they shall necessarily have occasion to cut down any wood to clear a path they shall leave it for the owner of the land.

Dated March yr. 9th 1710/[17]11 Samuel Appleton

William Goodhew

Jonathan Wade

In modern terms, what was done was this. The Committee surveyed the woodlands and divided them into lots to be distributed by draw among the proprietors. The question of access to those lots was then addressed as follows. First, the already-existing "highways, and paths" remained in place as they were. And second, "where a way [was] wanting" to get to a lot, the owners of those lots were given the privilege of constructing an access road "where it may be most convenient for them: with least prejudice to their neighbors' lotts that they pass through."

This "choose your own adventure" approach to road location is not as strange as it sounds, and was actually quite clever. Rather than imposing an arbitrary set of roadways through this previously undeveloped land, the Committee trusted the landowners themselves to work out the network best suited to their needs and the topography and wetlands of the area - the "most convenient" route for the lot owner, with the "least prejudice" to the lots the route went through. [Note 16] The community was small (all of the Proprietors likely knew each other personally), and the standard for the layout and dimensions of such roadways was well known to the law. When roadways are defined only by their general purpose - here, to give "convenient" access to the lots so created "with least prejudice" to the lots they passed through - their location and width is whatever is reasonably needed for that purpose "to be of practical use to the grantee" and "convenient . . . for all the uses of free passage to and from the land granted to him." See L. Jones, A Treatise on the Law of Easements, §364 at 292 & 293; §367 at 294 & 295 (1898) (hereafter, "Jones on Easements"); George v. Cox, 114 Mass. 382 , 387-388 (1874) (if width not specified in deed, grant is construed to convey "a way of convenient width for all the ordinary uses of free passage to and from his land"); Johnson v. Kinnicutt, 2 Cush. [56 Mass.] 153, 157-158 (1848). Importantly, the roadways so created are "not confined to the mode of use adopted at the time of the grant." Jones on Easements at §374 at 299; Mahon v. Tully, 245 Mass. 571 , 577 (1923) (when easement arises from grant or reservation rather than prescription, "the measure of that right is its availability for every reasonable use to which the dominant estate may be devoted, and this use may vary from time to time with what is necessary to constitute full enjoyment of the premises."); Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 172-173 (1948) (grant of general right of way in era of horse drawn vehicles "did not restrict its use to horse drawn vehicles or limit the way to the width of vehicles then in common use"); Marden v. Mallard Decoy Club Inc., 361 Mass. 105 , 107-108 (1972).

The result in this area was the woodland roadway network that exists today, including the eastern and western easements. See Exs. 1 - 4.

I took a view of the easements in connection with the trial, and their current state is this. Both are woodland roads, typical of their kind. [Note 17] Pond Street, where the eastern easement begins, is paved, and the easement roadway as it branches south off Pond Street has a gravel surface. There are dwellings on each side as far as the fork where the western easement starts. As the roadways go further into the woods towards the Gale parcel their surface changes to gravel and dirt, and then to hard-packed dirt. The surface is substantially flat and used by both cars and commercial vehicles which drive at slow speeds along it. They are well maintained for woodland roads of their type, and there was clear evidence of their regular use. This is particularly so of the eastern easement. [Note 18] Where the roadway goes through uneven or cross-sloped ground, it has been dug into that ground to keep it generally level. Judging by the diameters of their trunks, the trees on either side of the roadway are second growth or later, indicating that the land was logged in the past and likely used for pasture or farming. This is consistent with the deeds from the 1850's contained in the Land Court Title Examiner's Report (Trial Ex. 29) that describe the land in the area as "pasture" or "woodland pasture."

As measured by Gail Smith, a professional land surveyor employed by Mr. Gale whose testimony I fully credit, the main traveled surface of the eastern easement roadway in its current state varies in width from 9' to 20', and the presently usable width of the roadway (from the presently-existing tree trunk, earthen bank, or wall edge on one side of the roadway to the corresponding presently-existing tree trunk, earthen bank, or wall edge on the other) varies from 14' to 27'. See Trial Ex. 26. The Gale parcel connects to the eastern easement at the northeast corner of the parcel, and has no connection to it at the parcel's southeast corner or anyplace else. See Ex. 1. [Note 19] As measured by surveyor Smith, the traveled width of the western easement in the disputed section varies from 12' to 16', and the presently usable width from 13' to 17'. Id. The area between the traveled surface width and the usable roadway width on both easements acts (and is used) as a "shoulder" for vehicles to pull over to allow oncoming vehicles to pass. I find that the total usable width of both was likely wider in the past, and perhaps the traveled width as well, prior to the presently existing trees taking root and growing. Again, this is consistent with the early deed descriptions of the abutting land as "pasture" or "woodland pasture" (indicating that the land was more open in the past), and even more so from the easements' labels on old plans as "Old Road to Manchester" or "Old Road" [Note 20] - a label attached to both the eastern easement and the western easement, indicating that both likely were branches of the Manchester road and that that road was a relatively significant one in the not-too-distant past.

The current surface of the roadways is the result of relatively recent work. In the 1960's and 1970's the roadways were all dirt, with a rougher surface and more potholes than today. Cars are approximately 6' wide, so the roadway plus the pull-over (usable) space at that time was likely the same as it is today. Mr. Gale, his residential neighbor George Harvey to the north, and his commercial neighbor Charles Raymond to his east, have been the ones responsible for the improvements and maintenance to the eastern easement roadway in the areas past the fork where the western easement branches off - levelling, graveling, pothole filling, and snow plowing. MECT, whose visitors use the eastern easement roadway to get to MECT's parking area at the edge of its land, has taken advantage of these improvements and maintenance but has not participated or contributed to them. There was no evidence, physical or testimonial, that any trees had been cut down in connection with these recent improvements. To the contrary, the diameter of the trees along the sides is such that many likely grew into what had formerly been open area alongside the roadway. This is consistent with the roadway having been wider in the past.

For current use of the Gale parcel as a developable lot, a reasonable access roadway along the easements would be a minimum of 20'-wide - wide enough for two cars to pass with a shoulder for pull-overs, snow storage in the winter, the installation and maintenance of utilities, and drainage. I so find.

Further facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

MECT Has No Standing to Challenge the Western Easement

As previously noted, MECT has no standing to object to any part of the western easement. It owns no land that the western easement crosses, and the land it occupies is not served by that easement. See Hickey v. Pathways Ass'n, Inc. 472 Mass. 735 , 753 (2015) (standing to object to the use of an easement requires the objecting party to either have a fee interest in its underlying fee or to hold an easement interest of its own).

The Question of MECT's Standing to Challenge the Eastern Easement

There are issues with MECT's title to its land. I need not reach or resolve those issues, however, because for purposes of this litigation only, Mr. Gale and MECT have stipulated that MECT has sufficient title to pass the first test of "standing" to challenge the eastern easement. [Note 21] In any event, Mr. Gale "recognizes that MECT [has] an easement over the ROW [the eastern easement] in common with him and many others to access its property east and south of the [Gale parcel]," Post-Trial Brief of John W. Gale, Trustee of Inertia Realty Trust at 34, and this is sufficient to pass that first test. See Hickey, 472 Mass. at 753 ("Even without a fee in the way . . . easement holders have an interest in preventing use of the way by those without rights of access."). [Note 22]

What Mr. Gale does contest is whether his widening and improvement of the eastern easement would cause any reasonable likelihood of injury to MECT - a likelihood MECT must also prove to have standing to contest such widening or improvement (the second test). See Higby/Fulton Vineyard LLC v. Bd. of Health of Tisbury, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 848 , 850-852 (2007). Mr. Gale intends to build two houses on his land, one for each of his daughters, and it is not immediately apparent what effect, if any, those houses will have on MECT's property which is currently undeveloped and used only by hikers walking on its trails. Indeed, it is likely that it will have no such effect. Occupants and visitors to the Gale parcel will park on that parcel, not on MECT's land, and there is no particular reason for any of those occupants or visitors to go onto MECT's property for any purpose. To obtain building permits, Mr. Gale will need to have septic or sewer, so there should be no off-site impacts from that. [Note 23] Noise and light impacts by those houses onto the MECT land are speculative at best, and MECT offered no proof of any. There was no proof of any impact on plants or wildlife on the MECT land.

Perhaps in recognition of this, MECT raised specific concerns only about potential increased traffic on the roadway. But again it offered no proof of any resultant injury to its property. The number of vehicle trips that would be added to the easement by the two houses on the Gale parcel would be few, and how those additional cars would adversely affect the MECT land was not shown. Mr. Gale already drives on the easement to go to and from his land. So do the vehicles going to and from the commercial property, owned by Charles Raymond, that is located just past the Gale parcel. Indeed, MECT's own property has regular vehicular traffic as evidenced by the parking area it has established for hikers just off the easement. If anything, the effect on the MECT parcel from the widening and improvement of the easement to 20' would only be positive since the roadway would now be driveable in both directions at once, eliminating any vehicular conflicts and making access easier for everyone.

In any event, establishing adverse traffic and parking impacts requires expert testimony, and MECT offered none at trial. See Twardowski v. Ukstins, 19 LCR 431 , 436 (2011) (HMG) (expert evidence typically required to establish traffic and parking-based aggrievement); Nihtila v. City of Brockton Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 19 LCR 395 , 396 (2011) (HMG) ("[E]xpert knowledge and skill are required if one is to properly evaluate the impact of an alleged prospective increase in traffic and parking, as well as safety concerns of the sort alleged by the plaintiffs."); Kane v. Chan, 17 LCR 107 , 108 (2009) (KFS) ("[C]laims of harm ... due to ... traffic ... are required to be supported by expert evidence . . . ."); Martinonis v. Movalli, 15 LCR 532 , 534 (2007) (GHP)( "[I]ntuitive conclusions about what will and will not exacerbate traffic are not countenanced by the courts; real proof based on traffic engineering and expert study and analysis is required to prove traffic harms and to show their particular and specialized adverse effect on the plaintiff."); Hilltop Gardens Inv. LLC v. JMK Dev., LLC, 13 LCR 202 , 206 (2005) (KCL) ("Traffic impact is a matter for expert testimony."). See also Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 124 (2011) (speculative traffic flow and safety concerns insufficient to confer standing); Brookins v. Boston Zoning Comm'n, 24 LCR 643 , 647 (2016) (JCC) (plaintiff's "speculative and unsupported personal opinion" insufficient to establish aggrievement on basis of parking and traffic impacts); Lowell v. Marquis, 16 LCR 205 , 206 (2008) (KCL) (alleged traffic impacts, not supported by expert evidence, were "too speculative and remote to convey standing").

I need not and do not decide the question of MECT's standing, however. As discussed more fully below, Mr. Gale has proved his right to widen the easement to a uniform 20'-width on the merits, mooting the standing issue. See Mostyn v. Department of Envtl. Protection, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 788 , 792 & n.12 (2013) (standing need not be addressed "where the merits have been fully briefed and the question of standing is not outcome determinative").

Purported Width Restrictions

There are three places on the easements with purported width restrictions, identified on the attached Ex. 2 as "Way 1", "Way 2", and "Way 3." There is also a fourth area, not specifically shown on Ex. 2, which was included in a conservation restriction granted to MECT by the Madsens. I address them in turn.

"Way 1" simply reflects the section of the western easement where Mr. Gale has an express 20'-wide grant from the underlying fee owners. Since all he seeks is 20', this is not in controversy.

"Way 2" is the disputed section of the western easement - the short section between the beginning of that easement at the fork where it branches off the eastern easement, and ending at the property line immediately to the south of the fork (i.e. where "Way 1" begins). It was referred to as "the existing driveway, approximately ten feet (10') wide" in an agreement between the then-owners of three parcels, Bergmann, Favazza, and Harvey (Easement, Mar. 29, 1979; Trial Ex. 34 at 2), in which a mutual easement to use it was agreed between those parties. MECT contends that that 10' reference was intended as a 10' limitation. I disagree. Fairly read, 10' appears to be part of the easement's location reference - identifying that location by its then-existing use (driveway) and traveled width (10') - rather than a width limitation. But whichever interpretation is correct does not matter for Mr. Gale. Neither he nor the prior owners of his parcel were signatories to that agreement, and his parcel is thus not bound by its terms. Mr. Gale's rights in that section are independent of that agreement, and are discussed below.

That same document also grants its signatories a mutual easement in what is referenced as the "existing road, approximately fourteen feet (14') wide," referring to the portion of the eastern easement that runs over their land. Trial Ex. 34 at 2. This is shown as "Way 3" on the attached Ex. 2. MECT again argues that the width reference was intended as a width limitation, and again I disagree. Once more, fairly read, it appears to be simply a location reference - this is the road we're talking about - and, once more, it does not matter for Mr. Gale. Neither he nor his predecessor owners were signatories, and are thus not bound by its terms. Once more, his rights in that roadway are independent of that agreement, and are discussed below.

Finally, there is the Conservation Restriction granted to MECT by the Madsens which, in relevant part, purports to prohibit any improvement to the eastern easement - width, surface, or drainage - in the section that runs over the Madsens' land (the lot closest to Pond Street, see Ex. 2). Conservation Restriction, Madsen to MECT, at 2, ¶2(b) (May 19, 2003) (Trial Ex. 43). There are several problems with this purported restriction (among others, the fact that the Madsens' predecessors had previously designated the area as a 44'-wide "Future Road" on their recorded subdivision plan, Trial Ex. 8, and granted the other lot owners - Lots B, C & D - a right of way over its entire 44'-width "for all the usual purposes for which ways are commonly used in the Town of Essex"), [Note 24] but only one necessary to note. Since the Madsens were the only grantor of that restriction, it only binds them and the land they then owned, and only to the extent that their predecessors, the Bergmanns, had not already granted roadway improvement and development rights to the owners of parcels B, C, and D. The Madsens did not own, and never owned, any part of the Gale parcel. The Gale parcel is thus not subject to that restriction. Once again, its rights (discussed below) are independently based and completely unaffected.

The Gale Parcel's Rights of Access

Mr. Gale claims a 20'-wide easement over both the eastern easement roadway and the western easement roadway (1) by prescription, and (2) by express grant pursuant to the Ipswich proprietors' Roadway Grant in 1711. I address each of these claims in turn.

Prescriptive Rights

To establish an appurtenant prescriptive easement over another's land, a claimant must prove "use of the land in a manner that has been (a) open, (b) notorious, (c) adverse to the owner, and (d) continuous or uninterrupted over a period of no less than twenty years." Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007). The claimant must also show that his or her use "was substantially confined to a regular or specific path or route for which he might acquire an easement of passage by prescription." Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45.

Thus, the location and width of a prescriptive easement is not what the claimant would like. It is not what the purpose the claimant wants to use it for requires, nor what might be preferable for that purpose. It is only the area that was actually used. [Note 25] See id. See also Lawless v. Trumbull, 343 Mass. 561 , 562-563 (1962) ("The extent of an easement arising by prescription, unlike an easement by grant, is fixed by the use through which it was created. Prescriptive rights are measured by the extent of the actual adverse use of the servient property, not by the extent of the threats of the dominant owner") (internal citations and quotations omitted); Stucchi v. Colonna, 9 Mass. App. Ct. 851 , 851 (1980); Stone v. Perkins, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 265 , 267 (2003).

Here, the existence of a prescriptive easement in both locations claimed (the eastern easement and the western) has been conceded and proved. [Note 26] The affidavits of Luther and Hervey Burnham, admitted into evidence by agreement as part of the Land Court Title Examiner's Report (Trial Ex. 29), locate both roadways and attest to their use for the entirety of their lifetimes and their father's before them (Luther was born in 1891, Hervey in 1896, and their father in 1840), and I infer and so find that the roadways likely date back to the 1700's when this part of Essex was first settled and developed. [Note 27] The testimony was consistent that, with the exception of the recent improvements to their surface (graveling and grading by machine; they were previously primarily hard-packed dirt), the roadways were much then as they are today, with their locations the same, their traveled width the same, and their usable width likely somewhat wider, but how much wider and where is not determinable on this record. [Note 28]

Surveyor Gail Smith's plan measures the width of the traveled way on the eastern easement as varying between 9' and 20', and its usable width as between 14' and 27'. She measured the disputed section of the western easement as having a traveled width varying between 12' and 16', and a usable width varying between 13' and 17'. See Ex. 2 (Trial Ex. 26). I agree with Mr. Gale that the prescriptive area (the area actually used for twenty or more continuous years, openly, notoriously, regularly, and adversely) was the usable width, since vehicles encountering each other would have done so at any point along the roadway at any given time, and snow plowing would have used all available space to push the snow to the side. He has thus established a prescriptive right to use and improve those widths to their full extent for access to his parcel.

Mr. Gale wants more than this, of course. He seeks a declaration that his prescriptive rights are at least 20'-wide in all places along the easements based on an "averaging" theory. In essence, his theory is this. If you take an average of the widths at key points along the road, he says, that average is a little over 19' and, rounded up, should be construed as 20'. But there is no basis for such a theory as a matter of prescriptive rights. Prescription extends only to what was actually used, and cannot be rounded up or smoothed out. See Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45; Lawless, 343 Mass. at 562-563; Stucchi, 9 Mass. App. Ct. at 851; Stone, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 267. That is particularly so here where the roadways in question were laid out by the landowners themselves rather than a town agency tasked with uniformity. [Note 29]

This does not mean that Mr. Gale cannot prove in a future action that 20' was actually available and used for some twenty-year continuous period in the past. Such proof would suffice to establish prescriptive rights presently, assuming the extra width is not found to have been subsequently abandoned or extinguished. See Owens v. Buccheri, Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 89 Mass. App. Ct. 1115 , 2016 WL 1273143 at *1 (Mar. 31, 2016) ("Once the statutory period for adverse possession runs, the adverse possessor . . . becomes the lawful, actual possessor and the new 'real owner' entitled to bring a claim against even the record title owners."); Wolpe v. Haney, 2019 WL 5090528 at *14 (Mass. Land Ct., Oct. 10, 2019). I only find that he has not done so in this proceeding. As the claimant, Mr. Gale has the burden of proof. See Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009) ("The burden of proving every element of an easement by prescription rests entirely with the claimant. If any element remains unproven or left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail.") (internal quotations omitted). All he has proved in this proceeding is the widths shown on Trial Ex. 26. I accept and adopt those widths but, as a matter of prescriptive use, I can go no further.

Express Rights Pursuant to the Roadway Grant

As noted above and stipulated between the parties, the Gale parcel is one of the "lotts" referenced in the Roadway Grant and, as I have found, both the eastern easement and the western easement are access roads constructed by the lot owners pursuant to that grant. The grant was a general one - a "privilege in general for the proprietors that they may pass and repass over each [ ?] lott as they may have occasion where it may be most convenient for them: with least prejudice to their neighbors['] lotts that they pass through." It is thus to be construed by the principles applicable to such general grants that contain no express terms regarding their location or width. These are the same as the grant itself states: the right to a "convenient" way, suitable for all purposes to which the lot can be put, with "least prejudice" to the lots the way runs through. See Jones on Easements, §364 at 292 & 293; §367 at 294 & 295; George, 114 Mass. at 387-388 (if width not specified in deed, grant is construed to convey "a way of convenient width for all the ordinary uses of free passage to and from his land"); Johnson, 2 Cush. [56 Mass.] at 157-158.

Both the eastern and western easements have long-since been "located." They are where they are today, and those locations are not surprising. They track the topography and run along or near the boundaries of the lots themselves, providing access to each of them. Through long use, the lot owners have acquiesced in those locations and can hardly do otherwise; the Roadway Grant is in each of their title chains. For present purposes, the only open question is the width to which they can be developed and improved. Here again, the law both then and now is clear. Roadways created under a general grant such as this are "not confined to the mode of use adopted at the time of the grant." See Jones on Easements §374 at 299; Mahon, 245 Mass. at 577 (when easement arises from grant or reservation rather than prescription, "the measure of that right is its availability for every reasonable use to which the dominant estate may be devoted, and this use may vary from time to time with what is necessary to constitute full enjoyment of the premises."); Hodgkins, 323 Mass. at 172-173 (grant of general right of way in era of horse drawn vehicles "did not restrict its use to horse drawn vehicles or limit the way to the width of vehicles then in common use"); Marden, 361 Mass. at 107-108. See also Sprague v. Waite, 17 Pick. [34 Mass.] 309, 317 (1835) (noting that ancient ways laid out for public use may be widened beyond "the travelled path . . . as the increased travel and the exigencies of the public may require.").

Mr. Gale has not been greedy. He has not sought 44'-wide ways - the current subdivision requirement and, of note, the width shown on the Bergmann subdivision plan and deeded to the purchasers of his lots. See Trial Exs. 8 (subdivision plan) and 31, 32 & 33 (deeds). Rather, he seeks only 20' - the minimum practical width for development of his parcel into house lots (the 16' minimum roadway surface required by the Essex subdivision regulations, plus a 4' shoulder for vehicle pull overs, utility and drainage installation, and snow storage during the winter months). I find this to be eminently reasonable, and well within the rights to which he is entitled under the Roadway Grant. See cases cited above. I note as well that, with the exception of MECT, none of the abutters through whose land the ways pass has objected to a 20' width, and the present "prescriptive" width through MECT's own land is 19'. See Ex. 2.

Neither the western easement nor the eastern easement crosses any part of the Gale parcel. See Ex. 1. The parcel must thus link to those easements. MECT has challenged those links, not so much the western easement where Mr. Gale has an express right to do so from the fee owners of the land over which his access runs (and MECT has no standing to object, see discussion above) [Note 30] as the two places where Mr. Gale seeks to access the eastern easement. These are (1) at the northeast corner of his lot, where he currently has a long-standing access point, and (2) at his southeast corner, where a small part of the access point to the land he owns to the south cuts across the corner of the parcel at issue in this action. See Ex. 1. No extended discussion is necessary to answer these objections. Landowners have the right to access their access roads at reasonable places and the Roadway Grant expressly provides for this. The link at the northeast corner is the long-existing link and, just as the easement itself may be widened to 20' (and for the same reasons), it may be widened to 20' as well. The proposed link at the southeast corner is a different story. No link is presently there and, because a link already exists at the northeast corner, is one reasonably necessary in that location. The parcel to the south may be entitled to link to the eastern easement at that location (a question for another case on another day), but not this parcel. MECT has standing to object to link to the Gale parcel in this location because it owns the underlying fee in the land the link would cross over. See Ex. 1.

Conclusion

For the reasons set forth above, I find and declare that, subject to final review before the Certificate of Title issues, [Note 31] Mr. Gale has good title to the Gale parcel, proper for registration. He has an appurtenant right to pass and repass over the full length of the eastern easement and the full length of the western easement as far as the southern corners of his parcel, the right to link to the western easement at the present location of that link, and the right to link to the eastern easement at the northeast corner of his lot at the present location of that link. He has prescriptive rights to those easements and links to the widths shown on Ex. 2. He has express rights to those easements and links to a full 20' width. Those rights include the right to reasonable improvement of their roadways, and the right to install drainage and utilities within the widths of these easements.

In accordance with the principles set forth in the Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) §4.10 comment b (2000) and the Appeals Court in Pearson v. Bayview Associates Inc., Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28, 92 Mass. App. Ct. 1129 , 2018 WL 1023055 at *8 (Feb. 23, 2018) (in locating easements without defined locations, court to strike "a balance between minimizing the damage to the servient estate and maximizing the utility to the dominant estate, recognizing that the holder of an easement is entitled to use the servient estate in a manner that is reasonably necessary for the convenient enjoyment of the dominant estate . . . taking into account conditions at the dominant and servient estates as they exist at present.") (internal citations and quotations omitted), I find and declare that the 20' to which the easements and links may be widened and improved shall be measured from the center of the current traveled way, 10' to each side of the center.

Mr. Gale is directed to contact the Chief Title Examiner and the Chief Surveyor of the Land Court to complete the steps necessary for the registration of his parcel in accordance with this Decision.

SO ORDERED.

JOHN GALE as trustee of Inertia Realty Trust v. MANCHESTER ESSEX CONSERVATION TRUST, et al.

JOHN GALE as trustee of Inertia Realty Trust v. MANCHESTER ESSEX CONSERVATION TRUST, et al.