Introduction

Qiao Juan Gao and Lu Hong Lin (the Gaos) and Carlos P. Silva and Maria L. Silva (the Silvas) are next door neighbors. Their multi-family homes in Malden sit on either side of a common driveway. A dispute arose between them over this driveway. The Gaos obtained a survey of their property that disclosed that the fence enclosing their backyard excluded a wedge-shaped portion of their yard where it abuts the Silvas' backyard. After the Gaos brought this action for trespass, the Silvas brought a counterclaim for adverse possession over this wedge-shaped area. At trial, the parties stipulated that they had resolved the dispute over the driveway; the adverse possession was tried to me. After trial, I find that the Silvas and their predecessors in title have established that they actually, adversely, openly, notoriously, and exclusively used this area for a continuous twenty-year period, thereby giving them title by adverse possession over the area.

Procedural History

The Gaos filed their Complaint (Complaint) on July 23, 2018, naming the Silvas as defendants. The Complaint contains two counts: Count I, Encroachment, and Count II, Trespass. The case management conference was held on September 27, 2018. On March 6, 2019, the Silvas filed their Answer and Counterclaim, containing one counterclaim seeking to quiet title by adverse possession (Counterclaim).

The Pre-Trial Conference was held on July 23, 2019 before Judge Foster. Trial was held on December 10 and 11, 2019. Exhibits 1-15 were admitted, and Exhibits A and B were marked for identification. Testimony was heard from Charmaine Lee, Carlos Silva, Qiao Juan Gao, and Lu Hong Lin. The court took a view on December 11, 2019. The Plaintiff's Memorandum in Opposition to Defendant's Adverse Possession Claim and the Defendants' Post-Trial Memorandum were both filed on March 24, 2020. The court held a Post Trial Hearing and heard closing arguments on June 26, 2020 by video conference, and took the case under advisement. This Decision follows.

Facts

Based on the view [Note 1], the undisputed facts, the exhibits, the testimony at trial, and my assessment of credibility, I make the following findings of fact:

1. The Gaos are the owners of the property located at 10-12 Parsonage Road, Malden, Massachusetts (Gao property) by quitclaim deed from Charmaine A. Lee, dated July 24, 2014 and recorded at the Middlesex South Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 63965, Page 389. Exhs. 1, 2.

2. The Silvas are the owners of the property located at 6-8 Parsonage Road, Malden, Massachusetts (Silva property) by quitclaim deed from Mary A. Harrington, Trustee of the Harrington Family Trust and Guardian of Virginia B. Harrington, dated December 31, 1998 and recorded at the registry in Book 29614, Page 436. Exhs. 1, 3.

3. The Gao property and the Silva property share a boundary line running east to west from the rear, common border of the properties to Parsonage Road along the western border of the properties. Exh. 1.

4. The properties each have a multifamily house on their respective lots. The shared boundary line of the Gao property and the Silva property bisects a common driveway that lies between the multifamily homes on each lot. Behind the driveway, from the perspective of Parsonage Road, are the rear yards of the Gao property and the Silva property, which are separated by a black chain-link fence (the chain-link fence). Exhs. 8, 11-12; Tr. 1-39; View.

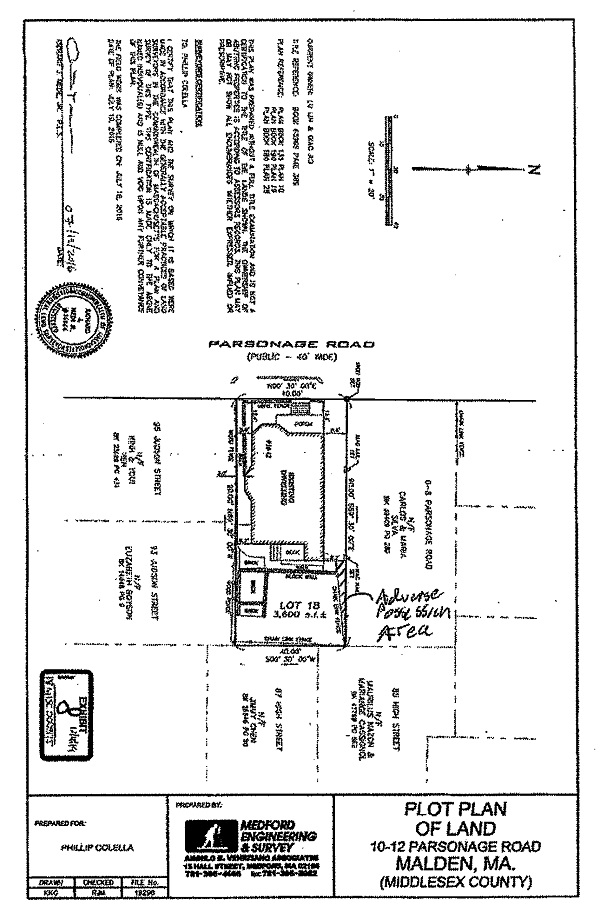

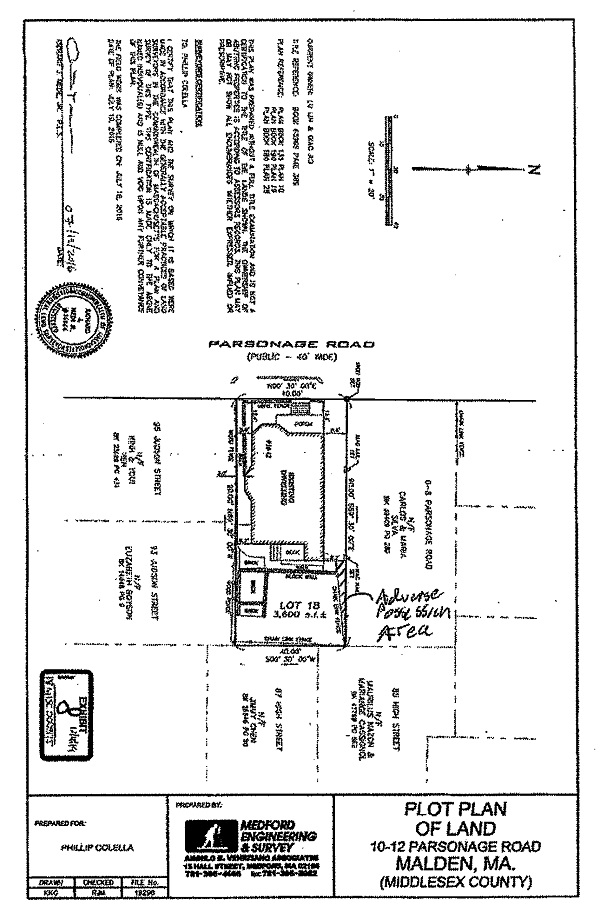

5. Sometime in early 2015, a dispute arose as to whether the Gaos had a right to park in the common driveway. After the dispute could not be settled, and on advice of the building department of the City of Malden, the Gaos hired a surveyor, Richard J. Mede, Jr. of Medford Engineering & Survey, to conduct a survey of the Gao Property. Mr. Mede completed a plan entitled "Plot Plan of Land 10-12 Parsonage Road Malden, MA. (Middlesex County)," dated July 18, 2016 (Mede survey). A copy of the Mede survey is attached as Exhibit A. Tr. 1-74-79, 2-18, 2-21-24, Exh. 8.

6. The Mede survey revealed that the chain-link fence between the two rear yards did not lie on the property line, but instead was angled inwards or southwesterly, such that there is a wedge-shaped area outside of the chain-link fence, and adjacent to the Silvas' rear yard, within the Gaos' property line. This wedge-shaped area, hereinafter referred to as the "adverse possession area," ends where the paved driveway begins, and is the subject of the Silvas' adverse possession claim. Exh. 8, Tr. 1-7-8; View.

7. The Mede Survey also shows that the property line bisects the driveway, leaving the Gaos with an approximately 8.4-foot-wide space to park their cars. The boundary line is shown on the driveway by a white marker several feet to the left of the chain-link fence. I credit the Mede Survey, and find that it accurately shows the boundary lines of the Gao property. At trial, the parties stipulated that there was no dispute over the boundary between their properties down the middle of the driveway as shown on the Mede survey. Tr. 1-5-7; Exhs. 8, 11A-11C; View.

8. Ms. Gao testified that she retrieved the survey sometime in 2017. She showed the survey to Mr. Silva in September of 2017 and asked him to remove his belongings from within the bounds of her property. I credit her testimony, and by agreement of the parties, I find that the Silvas were aware that the adverse possession area was not a part of their property as of September 24, 2017. Tr. 1-80-82, 1-90.

9. Charmaine Lee previously owned the Gao property. She purchased the property on December 25, 1998 from her parents, Herbert and June Roberts, and her aunt and uncle, Sonia and Nicholas McDonald. Prior to that transfer, Ms. Lee's parents and the McDonalds bought the property from her aunts Veta Gavin, Vivienne Wright, and Sonia McDonald on April 4, 1991. Ms. Lee testified that her aunts purchased the property sometime in the late 1980s. I credit her testimony. Tr. 1-15-17, Exhs. 4, 6.

10. Ms. Lee has been familiar with the Gao property since the late 1980s, when she would visit the property at least annually for family gatherings. She recalls the chain-link fence "always being there," dividing the backyards of the Gao property and Silva property. During the time that Ms. Lee and her parents owned the Gao property, Ms. Lee testified that none of them ever replaced the chain-link fence, nor made any alterations or repairs. I credit Ms. Lee's testimony, and find that the chain-link fence (including the gate) has been in that same location off of the boundary line since the late 1980s up to the present day. Tr. 1-17, 1-19, 1-20-21, Exh. 11C.

11. During the time she owned the property, Ms. Lee never limited the Silvas' use of the property on the other side of the chain-link fence. She never maintained the adverse possession area because she believed that her property ended at the fence. I credit her testimony. Tr. 1-22.

12. Ms. Lee lived at the Gao property beginning in 1995, as she rented the downstairs apartment before purchasing the property. She was familiar at that time with Mary and Virginia Harrington (the Harringtons), who previously owned the Silva property. Ms. Lee testified that the Harringtons maintained the backyard of the Silva property all the way up to the fence. She also recalls the adverse possession area being used by the Harringtons for parking throughout the time they lived at the Silva property. Ms. Lee did not recall the Silvas parking in the adverse possession area. I credit her testimony. Tr. 1-23-26, 1-37.

13. At the time that the Harringtons lived at the Silva property, the driveway was unpaved. It was paved "several years" after the Silvas moved in, paid for jointly by the Silvas and Ms. Lee. Tr. 1-26-27.

14. Ms. Lee testified that she never asked the Silvas to remove the white-slatted fence placed between their yard and the driveway, which lies partly in the adverse possession area. She testified that she believed that "where the fence ended was where [her] property ended." I credit this testimony. There was no evidence that she ever challenged the neighbors' use of the adverse possession area, or that she used or maintained that area herself. Tr. 1-28-29, Exh. 11C.

15. Carlos Silva testified that in the time he has lived at the Silva property, the chain link fence has always been in its present location, and it has never been replaced or repaired. In fact, at the time he purchased the home, the chain-link fence had plants growing in it, which he removed on his side. I credit this testimony, and find that Mr. Silva began maintaining his yard up to the chain-link fence at the time he moved into the Silva property. Tr. 1-22, 1-42-43, 1-65.

16. Mr. Silva testified that he placed the white plastic fence separating his yard from the driveway, which lies partially in the adverse possession area, in 2013 or 2014. The fence is held in place only by three planters in front of that fence, and the planter furthest to the right lies within the adverse possession area. I credit this testimony. Tr. 1-43-44, 1-67, Exh. 11; View.

17. Leaning up against the chain-link fence, and within the adverse possession area, is a plastic white-lattice panel, originally left-over porch material, which Mr. Silva has stored in that location since 2014 or 2015. Tr. 1-44-45, Exh. 11; View.

18. In front of the white lattice, and also within the adverse possession area, is a flower bed that abuts the chain-link fence all the way to the back of the Silvas' yard. Mr. Silva testified that he cares for those plantings daily, and uses mulch to care for them yearly. The flowers were planted by Ms. Silva. Tr. 1-45-46, 1-66, Exh. 11; View.

19. Also within the adverse possession area is the pole of a tent-like structure that lies within the Silvas' yard. The pole is affixed to the ground with cement. That structure was installed in 2001. Tr. 1-47-48, 1-66, Exh. 11; View.

20. According to Mr. Silva, Ms. Lee never spoke with him about repairing the chain link fence (or the chain-link fence generally), about the flower bed, or about the white fence by the driveway. Ms. Lee and Mr. Silva never exchanged letters or notes about any of the fences. Mr. Silva also testified that neither the Gaos nor the former owners of the Gao property ever gave him permission to use the adverse possession area. I credit Mr. Silva's testimony. Tr. 1-46-48.

21. Mr. Silva testified that the Silvas believed that the black chain-link fence was on the property line up until they were made aware of the Mede survey. I credit his testimony. Tr. 1-57.

Discussion

I. Adverse Possession

Legal Standard

"Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years." Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 621-622 (1992), quoting Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964); G. L. c. 260, § 21. The twenty-year period can be achieved by tacking the adverse possession of a predecessor if there is privity of estate between the plaintiff and the predecessor. G.L. c. 260, § 22. The person claiming title has the burden of proving adverse possession, and this burden "extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession." Mendonca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968), quoting Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949); Lawrence v. Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003).

After weighing all of the evidence, I find that the Silvas have title to the adverse possession area. The Silvas proved at trial that the chain-link fence existed in its present location continuously for the statutory 20-year prescriptive period, and that the Silvas and their predecessors in title continuously used the adverse possession area in a manner that was actual, open, notorious, exclusive, and adverse. As detailed below, I find that they have met their burden of proving adverse possession.

A. Continuous Use

The Silvas and their predecessors in title, the Harringtons, continuously used the adverse possession area outside of the chain-link fence. Exh. 8. Ms. Lee testified that since at least 1995, when she began living at the Gao property, the Harringtons maintained the backyard up to their fence, and parked their cars in the adverse possession area. Tr. 1-23-26. Then, when the Silvas came to own the property in 1998, they began maintaining the adverse possession area, first by trimming the plants growing along the chain-link fence on his side, then planting a bed of flowers and maintaining it until the present-day. Tr. 1-43, Tr. 1-45-46, 1-66, Exh. 11. Since they have lived at the Silva property, the Silvas have also used the adverse possession area to erect a tent-like structure, secure a white plastic fence to separate their yard and the driveway, and to store a spare white-lattice panel. Tr. 1-43-45, 1-47-48. Therefore, by the time the Silvas were

put on notice in September 2017 that the adverse possession area was not a part of their yard, but in fact belonged the Gaos, the Silvas and the Harringtons before them had continuously used that area for at least 22 years.

B. Open and Notorious Use

"The purpose of the requirement of 'open and notorious' use is to place the true owner 'on notice of the hostile activity of the possession so that he, the owner, may have an opportunity to take steps to vindicate his rights by legal action." Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421, quoting Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333 (1959). Explicit notice of adverse use is not required. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421; Ottavia, 338 Mass. at 334 ("Where the user has acted, without license or permission of the true owner, in a manner inconsistent with the true owner's rights, the acts alone ... may be sufficient to put the true owner on notice of the nonpermissive use"); Poignard v. Smith, 23 Mass. 172 , 178 (1828) (where true owners were both out of the state, adverse possession was still found because "acts of notoriety, such as building a fence round the land or erecting buildings upon it, are notice to all the world"). "Open and notorious use of a property is thus

deemed to place the true owner on constructive notice of such use, and it is immaterial whether the true owner actually learns of that use or not." Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 422. For use to be open, "the use must be without attempted concealment;" to be notorious, "it must be sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property." Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007).

Here, the Silvas' and the Harringtons' use of the adverse possession area was open and notorious. While the Harringtons lived next door to Ms. Lee, they maintained the adverse possession area, and used it for parking. Tr. 1-24-26. Parking can be open and notorious use of land, see, e.g., Patrick J. Gill & Sons, Inc. v. Moskow, 3 LCR 86 (1995) (Kilborn, J.), and here the backyards are visible from the driveway and the street. Tr. 1-39, Exh. 11, View. Indeed, Ms. Lee had actual notice, as she testified as to the Harringtons' use of maintaining the adverse possession area and parking on it. Tr. 1-24-26. The Silvas' use was also sufficient to place the true owners (first Ms. Lee, then the Gaos) on notice of the non-permissive use: trimming plants on their side of the chain-link fence, planting a flower bed, and installing the tent-like structure pole in the groundall visible from the Gao property, from the driveway, and the street. Exh. 11; View. Having found that the Harringtons' and the Silvas' use was open

and notorious since at least 1995, and up until the present day, I find that the use was open and notorious for the requisite statutory period.

C. Exclusivity

"A claimant's use is 'exclusive' for purposes of establishing title by adverse possession if such use excludes not only the record owner but 'all third persons to the extent that the owner would have excluded them.'" Brandao v. DoCanto, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 151 , 158 (2011), quoting Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 557 (1993). To demonstrate exclusivity, "[s]uch use must encompass a 'disseisin' of the record owner." Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 557. "That is to say, a use or possession which is not adverse to the owner, or which is concurrent with that of others, or which does not exclude a similar use or possession by others, will not confer a title in fee, however long continued." Eastern R.R. Co. v. Allen, 135 Mass, 13, 16 (1883). "Acts of enclosure or cultivation are evidence of exclusive possession." Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 349 (1967).

Here, there is no evidence that Ms. Lee or the Gaos ever used the adverse possession area. The chain-link fence, enclosing the Gao yard, made it appear (and all the parties so believed) that the adverse possession area was a part of the Silva property, and was always treated as such. I find, therefore, that the adverse possession area was used exclusively by the Silvas and their predecessors, the Harringtons, from at least 1995 up until the survey was completed and delivered to the Silvas in 2017.

D. Adverse/Non-permissive Use

The essence of adverse possession is that the possessor's use of the land must be adverse or hostile to the true owners, meaning that the use is without permission of the owners. Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145 (2000). "The essence of nonpermissive use is lack of consent from the true owner." Id.; see Ottavia, 338 Mass. at 333334. Accordingly, if the true owners give permission to use their land, there can be no adverse possession. Kendall, 413 Mass. at 623. "One's use of another person's property is adverse to that person if the manner of his use and the circumstances thereof demonstrate that he does not recognize or consider himself to be subject to an authority in that person to prevent his use of the property." Bills v. Nunno, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 279 , 284 (1976). "It is well established in Massachusetts that permissive use based on a mutual mistake as to the location of a boundary line will not defeat a claim of adverse possession." Kendall, 413 Mass. at 622. The possessor's subjective state of mind

or intent is irrelevant to a claim of adverse possession. Id. at 623. One can obtain title by adverse possession even if he or she does not intend to deprive another of property. Flynn v. Korsack, 343 Mass. 15 , 18-19 (1961); Van Allen v. Sweet, 239 Mass. 571 , 574575 (1921). Thus, even if the possessors believe their use is permissive because of a mistake as to titles or the location of a boundary line with adjoining land, their claim is not defeated so long as the nature of the use and resulting occupancy of the land is sufficient to indicate adversity. Kendall, 413 Mass. at 622623; Boutin v. Perreault, 343 Mass. 329 , 331-332 (1961).

Here, there was no evidence presented at trial that the owners of the Gao property ever granted permission to the owners of the Silva property to use the adverse possession area. Ms. Lee never spoke with Mr. Silva about his use of the adverse possession area, nor gave him permission to use it. Tr. 1-28-29, 1-48. Similarly, there is no evidence that Ms. Lee ever challenged the Harringtons' use of the adverse possession area or granted them permission to use it. The Gaos did not challenge the Silvas' use of the adverse possession area until September 24, 2017. Tr. 1-80-82, 1-90.

For as long as Ms. Lee lived at the Gao property, and up until the Gaos acquired their survey showing otherwise, Ms. Lee and the Silvas believed and behaved as though the adverse possession area was part of the Silva property, and there is no evidence before me that the Gaos believed the adverse possession area to be a part of their property until they received the survey, Tr. 1-28, 1-57, 2-27. The Silvas and the Harringtons did not"consider [themselves] to be subject to an authority ... to prevent [their] use of the property." Bills, 4 Mass. App. Ct. at 284. Therefore, from at least 1995 until 2017, the Silvas and the Harringtons used the adverse possession area in a manner adverse and non-permissive.

I find, based on the evidence, that the Harringtons and the Silvas occupied and used the adverse possession area adversely, openly, notoriously, exclusively, and continuously between 1995 and 2017, a period of more than twenty years. Twenty years from 1995 is 2015. Thus, the Silvas have established title by adverse possession to this adverse possession area, title that ripened in 2015.

II. Encroachment and Trespass

The Gaos' Complaint contains two claims: Count I, Encroachment, and Count II, Trespass. An individual "who intentionally enters land in the possession of another is subject to liability to the possessor for a trespass, although his presence on the land causes no harm to the land, its possessor, or to any thing or person in whose security the possessor has a legally protected interest." Restatement (Second) of Torts § 163 (1965). A plaintiff who proves that the defendant committed an intentional, unprivileged trespass to his real property is entitled to recover nominal damages, even if no actual damage is shown. Lawrence v. O'Neill, 317 Mass. 393 , 395 (1944); Cumberland Corp. v. Metropoulos, 241 Mass. 491 , 503 (1922).

To prevail in an action for trespass, the plaintiff must show that he or she had actual possession of the real property or a right to possession of the property at the time of the trespass. Attorney Gen. v. Dime Sav, Bank of N.Y., FSB, 413 Mass. 284 , 288 (1992); Federal Nat'l Mortgage Ass'n v. Gordon, 91 Mass. App. Ct. 527 , 536 (2017). One is in possession of land if they (1) are in occupancy with intent to control the property, (2) were formerly in occupancy with intent to control if no other person has obtained possession, or (3) have the right to immediate occupancy if no other person is in possession. Restatement (Second) of Torts § 157 (1965).

To the extent that the encroachment and trespass claims concern the common driveway, the parties have resolved that dispute. With respect to the adverse possession area, the Silvas and their predecessors began using the adverse possession area sometime in the early 1990s, but no later than 1995. Having found that the Silvas' adverse possession has ripened into ownership as of 2015, the Gaos' claims of encroachment and trespass fail, because they do not own the property (the adverse possession area) that is claimed to be encroached or trespassed upon. Therefore, the Gaos' claims of encroachment and trespass must be dismissed.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find that the Silvas have acquired title to the adverse possession area by adverse possession, and therefore the Silvas have not committed trespass and are not encroaching on the Gao property. The claims of the Complaint with respect to the common driveway shall be dismissed without prejudice and the claims of the Complaint with respect to the adverse possession area shall be dismissed with prejudice. On the Counterclaim, judgment shall enter declaring that the Silvas have acquired title to the adverse possession area by adverse possession.

Judgment Accordingly.

Exhibit A

QIAO JUAN GAO and LU HONG LIN, Plaintiffs v. CARLOS P. SILVA a/k/a CARLOS P. DASILVA and MARIA L. SILVA a/k/a MARIA L. DASILVA, Defendants

QIAO JUAN GAO and LU HONG LIN, Plaintiffs v. CARLOS P. SILVA a/k/a CARLOS P. DASILVA and MARIA L. SILVA a/k/a MARIA L. DASILVA, Defendants