Introduction

This case concerns the existence and scope of an easement on defendant William Ciminos [Note 1] commercial property at 580 Main Street in Wilmington, which was sold to him by plaintiffs Fred F. Cain, Inc. (FFC) and FFCs principal Fred Cain. [Note 2] The easement benefits FFCs property at 10 Ranch Road, behind 580 Main Street, which it retained after it sold 580 Main Street to Mr. Cimino.

580 Main Street, under Mr. Cains ownership and now under Mr. Ciminos, has always been used as a car dealership. At the time of the sale, as noted above, Mr. Cain retained ownership of a small lot of land, bordering the back of the dealership, which contains a two story building (#10 Ranch Road). The top floor of the building is rented to a residential tenant and Mr. Cain uses the bottom floor to operate FFCs towing business. Tow trucks come and go at all hours.

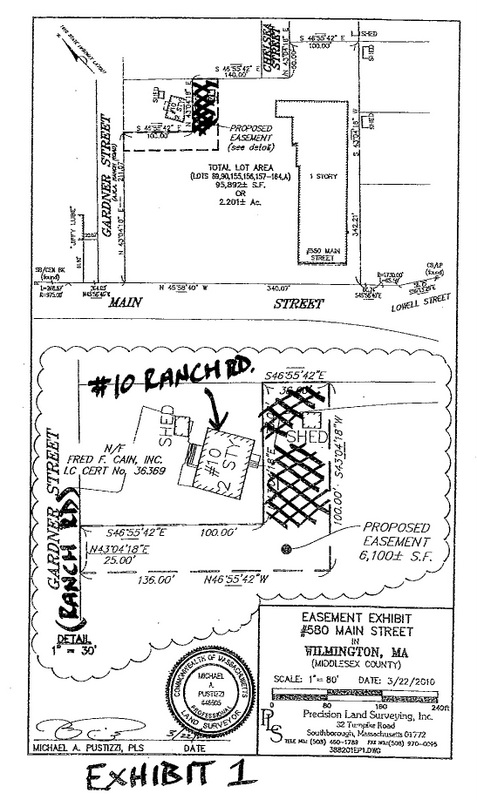

The parties negotiated the terms of the sale of the dealership property over the course of many months. A central part of those terms, set forth in the final, executed sale agreement, was Mr. Ciminos grant of an Exclusive Access and Use Easement over the dealership property for the benefit of 10 Ranch Road. [Note 3] The easement runs from Ranch Road (formerly Gardner Street) along the southern side of Mr. Cains property (10 Ranch Road), and then bends in an L-shape around its eastern side. See Plan of Easement, attached as Exhibit 1. The easement provides access to the two story building, and the parties agree that the eastern portion of the L (cross-hatched on Ex. 1) was intended solely for Mr. Cains use, including parking for his tow trucks and residential tenants and the location of storage sheds. [Note 4] At issue is the southern portion of the L the non-cross-hatched part.

Mr. Cain contends that the words Exclusive Access and Use Easement mean that only his property has the right to use the easement area, both east and south, for any purpose whatsoever. The word Exclusive, in his view, was intended to prohibit any use of any part of the easement by Mr. Cimino (the owner of the underlying fee) or any third-party tenant to whom Mr. Cimino might rent part of his building. [Note 5] Mr. Cimino contests that view with respect to the southern portion of the easement on essentially two theories. First, despite having signed the sale agreement with its easement language, he contends that no easement actually exists, only an agreement to agree on an easement at some future date, never consummated. Second, he says, if there was an easement agreement, exclusive meant only that Mr. Cimino could not grant rights to any property owner other than Mr. Cain. In Mr. Ciminos view, both he and any third-party tenant to whom he chooses to rent space on his property (580 Main Street) have full use of the southern portion of the easement so long as that use does not interfere with the Cain propertys access rights.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule (1) Mr. Cimino granted Mr. Cain an express easement on the terms contained in the sales agreement; it was not just an agreement to agree, never consummated, (2) as the parties agree, only the Cain property has the right to use the eastern, cross-hatched portion of the easement, no one else, and (3) with respect to the remainder of the easement (the southern, non-cross-hatched part), the word Exclusive, as intended by the parties, means that that easement area is for the exclusive use by the Cain property and may not be used by any other third party, whether a tenant on the Cimino land or anyone else, but does not preclude use by Mr. Cimino (the owner of the servient estate) in connection with his own business operations so long as that use does not interfere with access to and from the Cain parcel.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

580 Main Street and the Management Agreement

580 Main Street is located on Route 38 in Wilmington. Prior to its sale to Mr. Cimino, it was owned by Fred F. Cain, Inc. (FFC), a family-owned corporation originally formed in 1940. Plaintiff Fred Cain is the principal of FFC and, until January 30, 2004, owned FFC as an equal partner with his brother James. Freds son Stephen manages FFCs day-to-day business. For ease of reference, as previously noted, both FFC and Fred Cain shall collectively be referred to as Mr. Cain.

During the period of his ownership, Mr. Cain used 580 Main Street as a car dealership, first operating a Chrysler franchise until 1999 and then selling used cars until 2004. Mr. Cain also owns, and continues to own, a commercial rental property at 579 Main Street (across Route 38 from the car dealership) and a residential/commercial property at 10 Ranch Road, bordering the back of the dealership. In addition to owning this real estate, he also owns and operates a tow truck business.

William Cimino is the principal of PR356 LLC (for ease of reference, both are hereafter referred to as Mr. Cimono). He began his career as a car salesman in 1983 with Peter Fuller Jr., the owner of a Cadillac and other dealerships. Mr. Cimino advanced through the company into management roles and, around 2001, began looking for his own dealership. With his background, he was confident he could obtain a dealership of some sort; the challenge was finding an available one with an open location. From his experience, he concluded it was better to own the dealership real estate rather than lose profits by paying rent to a landlord each month. Thus, from his perspective, it was imperative to find a dealership property he could own.

Mr. Cimino began his search by speaking to a Mitsubishi representative about locations and properties that might be suitable for a franchise. He was advised to look along Route 38 and, while driving there in 2003, saw Mr. Cains used car dealership at 580 Main Street and decided to approach him.

Mr. Cimino had something of a chicken and egg problem. He could not get a car dealership license from the Town of Wilmington without first having his own car franchise, but could not get a franchise without a location. He thus entered into a management and lease agreement with Mr. Cain (Management Agreement) on January 30, 2004, which allowed him to operate under Mr. Cains dealership license as an independent contractor. More important for Mr. Cimino, the Management Agreement gave him the option to purchase the dealership property once he obtained his own franchise.

While operating under Mr. Cains license, Mr. Cimino spent some of his own money to upgrade the carpet and ceiling tiles in an effort to improve the propertys overall appearance and thus increase sales. He also acquired a newer inventory of used cars. These enabled him significantly to increase his earnings. Mr. Cain was indifferent to this since he was only receiving a fixed rent, unrelated to sales volume. [Note 6] Meanwhile, Mr. Cain continued to maintain an office in the dealership building from which he ran his tow business. Cars that were towed by Mr. Cains trucks were parked in a pen located on the Ranch Road property.

After a year of operating under Mr. Cains license, Mr. Cimino acquired a Cross Lander USA franchise [Note 7] and, with that in hand, was able to obtain his own license from Wilmington in December 2004. Thereafter, as the Management Agreement provided, he began operating his own business under the name Cimino Automotive Inc. (CAI), leasing the dealership from Mr. Cain. Pursuant to the terms of the Management Agreement, now that Mr. Cimino was running his own business, Mr. Cain moved his office from the dealership showroom to the back of the dealership building.

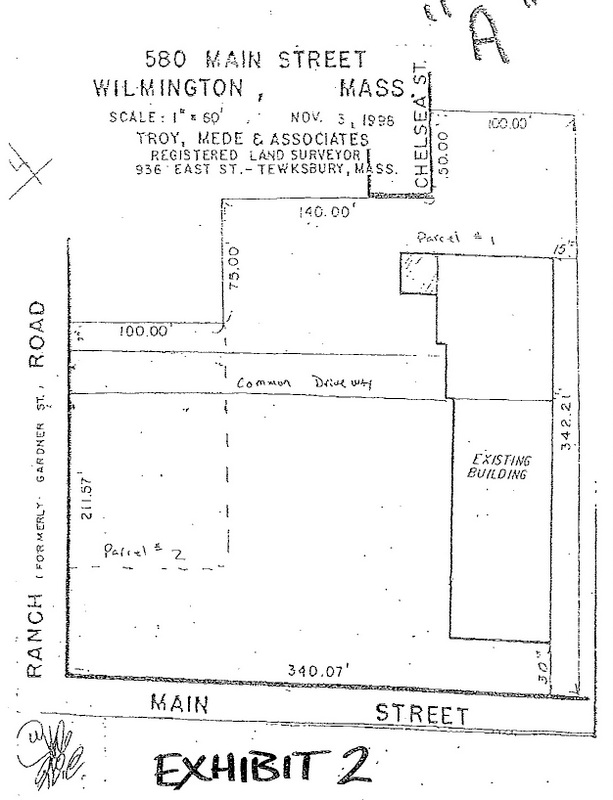

The relationship between Mr. Cimino and Mr. Cain, both during the management phase and then during the lease, was contentious. There were numerous disagreements about who should pay for maintenance costs for the building and almost continuous disputes over rent payments. Among those disputes, once Mr. Cimino began operating his own business, were Mr. Ciminos objections to Mr. Cains tow trucks driving through the dealership lot from the Main Street entrance along the side of the building. Resorting to self-help, he began to park cars along the Main Street entrance to block Mr. Cains trucks and insisted that the tow trucks enter from a common driveway running from Ranch Road that was depicted on a property plan that had been attached to the Management Agreement. See Exhibit 2, attached.

These disputes eventually led to litigation. Mr. Cain sought to evict Mr. Cimino and Mr. Cimino counter-claimed for the money he had spent on the dealership building for repairs and upgrades. For reasons not entirely clear from the testimony, Mr. Cains brother, James, also filed suit against Mr. Cain. In an effort to resolve these disputes, the parties and their attorneys met at the dealership in August 2005. Ultimately, they agreed that the lawsuits would remain pending but the eviction notice against Mr. Cimino would be withdrawn. It was also agreed that Mr. Cimino would receive some credit for the money he had spent if he decided to exercise his option to purchase the property in the future.

Around the same time in August 2005, Mitsubishi contacted Mr. Cimino to see if he was still interested in a Mitsubishi franchise. He was. To get it, he spent approximately $75,000 to redo the signage at the dealership and acquire the tools necessary to service Mitsubishi cars. He was then awarded the franchise, and began operating it from the 580 Main Street location in March 2006. All told, from the time he first entered into the Management Agreement with Mr. Cain, Mr. Cimino claims to have spent between $250,000 to $300,000 on building-related repairs, improvements, additions and alterations, including the $75,000 in signage and other costs associated with the Mitsubishi franchise.

The Sale of 580 Main Street to PR356

During the spring of 2009, Mr. Cimino gave notice of his intent to exercise his option to purchase the 580 Main Street dealership property. The parties retained counsel and engaged in lengthy negotiations from October 2009 until the closing in March 2010. Because the transaction involved the resolution of other outstanding issues between the parties, Mr. Cains attorney, Robert Peterson, drafted an Agreement containing all the essential terms and conditions involved in the deal. The Agreement was drafted in addition to the usual closing papers and deed, and the parties intended it to survive the closing. Under the Agreement, the purchase price was reduced from the $2.8 million figure first stated in the option to $2.4 million. The reasons for this price reduction are not stated in the Agreement, and both Mr. Cain and Mr. Cimino gave different explanations. I find that the $400,000 reduction was simply an agreed figure, not tied to or reflective of anything in particular. Mr. Cain also granted a right of first refusal to Mr. Cimino to purchase the Ranch Road property if Mr. Cain decided to sell the property outside his family. This had value to Mr. Cimino because the dealership has grandfather protection as a nonconforming lot, having less than the 100,000 square feet required by the Town of Wilmington for car dealerships. The addition of the Ranch Road property would make the dealership a legally conforming lot under the Wilmington zoning bylaw.

The easement at issue in this action is the subject of paragraph 10 in the Agreement, initially drafted by Attorney Peterson but then reviewed in detail and amended at the closing. Paragraph 10, as amended (the amendments are italicized), provides as follows:

Subsequent to closing, FFC [Cain] shall retain ownership of the real estate at 10 Ranch Road, Wilmington MA [the two-story building referenced above]

This is a residential dwelling containing approximately 7,500 square feet of land.

Pursuant to a separate Agreement by and between FFC [Cain] and PR356[Cimino], [Note 8] PR356 [Cimino] has agreed to give an Exclusive Access and Use Easement to FFC, which access and use easement shall be consistent with the Easement Plan attached hereto and incorporated herein by reference. The easement area is shown on an Easement Exhibit as prepared for PR356 [Cimino] by Precision Land Surveying Inc., dated March 22, 2010, a copy of which is attached hereto and incorporated herein by reference. [Note 9] At the time of closing as contemplated by this Agreement, said Easement Plan and drafted Exclusive Access and Use Easements from PR356 [Cimino] to FFC [Cain] were not finalized. [Note 10]

Subsequent to closing, PR356 [Cimino] shall pay Precision Land Surveying Inc. to complete an easement plan, in recordable form, for the benefit of FFC [Cain], which plan shall be substantially the same in form as the proposed Easement Exhibit attached hereto. Said plan shall be prepared at the sole cost and expense of PR356 [Cimino], and shall be completed no later than 30 days after the sale of 580 Main Street [the car dealership property] to PR356 [Cimino] by FFC [Cain].

Subsequent to closing, PR356 [Cimino] shall also engage PR356s [Ciminos] counsel, Michael Rubin of Rubin, Weisman, Colasanti, Kajko & Stein, LLP, of 430 Bedford Street, Suite 90, Lexington, MA to draft an Exclusive Use and Access Easement for the benefit of FFC [Cain] as contemplated by the Easement Exhibit attached hereto and incorporated herein by reference. Said easement shall be drafted in recordable form, with such easement language as may be agreeable to counsel to FFC [Cain], Robert G. Peterson, 314 Main Street, Wilmington, MA 01887. Said easements shall be completed by counsel to [Cimono], no later than 30 days after the sale of 580 Main Street to PR356 [Cimino] by FFC [Cain].

All expenses over $400 relative to the preparation and recording of the easement plan and easement documents shall be the sole responsibility of PR356 [Cimino].

Agreement at 3-4, ¶10 (Mar. 24, 2010) (Trial Ex. 9).

The closing took place on March 24, 2010. The parties were present and were assisted by counsel, Attorney Peterson for Mr. Cain and Attorney Michael Rubin for Mr. Cimino. As noted above, the parties reviewed the Agreement in detail with their attorneys and made a number of changes before signing it. However, neither the parties nor their attorneys had any discussion either earlier, then, or at any time prior to the signing of the Agreement regarding the meaning of the term Exclusive. Each was content with the word itself.

As noted above, the Agreement contemplated the creation of an easement document in a form suitable for registration. [Note 11] By the terms of the Agreement, these were initially to be drafted by Mr. Ciminos lawyer, Attorney Rubin. After nothing was sent within the 30 days, Attorney Peterson contacted Attorney Rubin, and Attorney Rubin delegated the task to his then-associate, Attorney Nellie Rosen. He did not, however, provide her with a copy of the Agreement or tell her what it provided. Instead, he simply requested her to draft an easement without giving her any guidance as to what it should say. Attorney Rosen put together a generic document, clearly never proofread, [Note 12] and, on May 14, 2010, emailed it to Attorney Peterson along with a copy of the Precision Land Surveying plan depicting the easement area. The granting language in her draft was as follows:

the perpetual right and easement, in common with others entitled thereto, to use for access by foot and motor vehicle, to #10 Gardner Street, Wilmington as shown thereon, but not for parking of same as shown on sketch plan of land entitled, Easement Exhibit # 580 Main Street in Wilmington, MA (Middlesex County) dated March 22, 2010 prepared by Precision Land Surveying, Inc. (hereinafter the Plan), attached hereto and made a part hereof, for the benefit of and appurtenant to _______ shown on said Plan, in common with the Grantor its successors and assigns.

Easement Draft, May 14, 2010 (Trial Ex. 10). Attorney Peterson glanced at the draft and immediately objected to its language as inconsistent with the term exclusive as intended and used in the parties signed Agreement. [Note 13] Attorney Peterson spoke briefly with Attorney Rubin after receiving the draft easement, noting his objections and requesting accurate language but, as the summer went on, Attorney Rubin never provided another draft. On November 16, 2010, frustrated at this, Attorney Peterson sent Attorney Rubin a letter, stating in relevant part:

Paragraph 10 of the Agreement between PR356 LLC [Cimono] and Fred F. Cain Inc. [Cain] dated March 24, 2010 calls for PR356 [Cimono] to give an exclusive access and use easement to Fred F. Cain Inc, [Cain] and which easement was to be consistent with the sketch drawn by Precision Land Surveying Inc. dated March 22, 2010

.I have been trying to draft this easement to get it recorded for some time. However, Fred informs me that Bill Cimino is now intimating that the easement will be something other than exclusive. This is unacceptable to Fred. The Agreement referred to above was very specific as to the exclusivity of the easement. As a matter of fact, the exclusive use easement contemplated by the Agreement was one of the reasons that Fred agreed to reduce the original purchase price between the parties. It is also the reason that Bill has a right of first refusal to purchase the property [10 Ranch Road] in the event the Cains wish to sell it. It is Freds position that the final easement between the parties will and should be consistent with the original signed Agreement. If Bill has other intentions, please let me know immediately so that Fred may take the appropriate actions to protect his interests.

Letter from Attorney Peterson to Attorney Rubin, November 16, 2010 (Trial Ex. 14). Attorney Rubin did not respond.

Pursuant to the Agreement, Mr. Cain remained in the back portion of the dealership building, now leasing that space from Mr. Cimino, until August 31, 2011 when Mr. Cain moved to the Ranch Road property. After Mr. Cain left the dealership property, Mr. Cimino began leasing that space to two third-party tenants, M.J. Landscaping and J.C. Welding, who began using the southern portion of the easement for vehicular access, apparently at the instruction of Mr. Cimino. Mr. Cain is opposed to any use of any part of the easement by either Mr. Cimino or Ciminos tenants and brought this action.

Additional facts are discussed in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

With the parties agreement on the eastern part of the easement (only Mr. Cain may use it, for any purpose), there are presently only two issues in contention: whether an easement agreement exists at all and, if so, what the parties intended by their use of the word exclusive with respect to the southern part. I discuss each of these in turn.

An express easement must be in writing and described with reasonable certainty. See Mason v. Albert, 243 Mass. 433 , 437 (1923). The March 2010 Agreement, in writing and signed, is sufficient. It states that PR356 [Cimino] has agreed to give an Exclusive Access and Use Easement to FFC [Cain]

Agreement at 3 (emphasis added). It describes the easement area with certainty by reference to the Easement Exhibit prepared by Precision Land Surveying. All that remained was to put the easement in the technical form necessary for registration in connection with the certificates of title for the burdened land. I thus reject Mr. Ciminos contention that there was only an agreement to agree on an easement in the future, or, at best, a license. [Note 14]

The central dispute in this action concerns the scope of the easement. What did the parties intend when they described the easement as an Exclusive Access and Use Easement? The plaintiffs have the burden of proving the nature and extent of the easement. See Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 24 n.1 (2006). When the language of a contract is unambiguous, its interpretation is a question of law for the court, and the terms must be construed in accordance with their ordinary and usual meanings. See World Species List Natural Features Registry Institute v. Reading, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 302 , 309 (2009). If a contract, however, has terms that are ambiguous, uncertain, or equivocal, the intent of the parties is a question of fact to be determined at trial. See Seaco Insurance Co. v. Barbosa, 435 Mass. 772 , 779 (2002). A contractual term is ambiguous if it is susceptible to more than one meaning and reasonable persons could differ as to which one is proper. See Sullivan v. Southland Life Ins. Co., 67 Mass. App. Ct. 439 , 443 (2006). When construing an ambiguous term, the court looks to the language used in the context of its surrounding facts and circumstances to ascertain the intent of the parties. See Mass. Municipal Wholesale Electric Co. v. Town of Danvers, 411 Mass. 39 , 45-46 (1991).

Mr. Cain contends the term exclusive as used in the Agreement is clear and unambiguous and should be construed in accordance with its ordinary dictionary definition. [Note 15] I disagree. By itself, the term is ambiguous. [Note 16] As the capitalization showsExclusive Access and Use Easement it was clearly a defined term. But it was never defined in the Agreement, and it was never discussed or clarified in the course of the negotiations between the parties. Despite Mr. Cains insistence that Mr. Cimino knew what exclusive meant based upon the parties prior use of that term in the Management Agreement, exclusive when used in the context of an easement agreement can mean something much different than granting an exclusive right to manage a business.

Exclusive in the context of an easement can be interpreted two different ways. One is that exclusive means the benefited property (Cain and his tenants) have the right to use the easement along with Mr. Cimino who owns the underlying fee, and Mr. Cimino may not grant that right to any other party. This interpretation conforms to the long held rule that the owner of the servient estate may make all beneficial use of his property so long as it is consistent with the rights of the easement holder. See M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 91 (2004) (and cases cited therein). A second interpretationthe one argued by Mr. Cainis that exclusive means only the Cain property may use it, for any purposeeffectively depriving Mr. Cimino of all rights in the land. If the parties had intended that meaning, something very different from the black-letter law, it was not stated expressly in the Agreement. See 28 Mass. Prac. Series § 8.4 (4th. Ed. 2004) (the drafter of an exclusive easement should specify whether everyone including the servient estate holder can be excluded from using the easement).

Since the meaning of exclusive cannot unambiguously be ascertained from the face of the Agreement, I turn to the surrounding facts and circumstances to determine the intent of the parties.

Communications between the parties during their negotiations show the easement was always meant to be mutually agreeable to the parties. Letter of Intent, circulated via email on December 15, 2009 (Trial Exhibit 5) (Cimino agrees to issue a mutually acceptable easement to FFC). This is so not only as a matter of law (there can be no contractual agreement without mutual assent, express or implied), but also because the easement was clearly important to both Mr. Cain and Mr. Cimino, albeit for different reasons. The facts and circumstances surrounding the eastern part of the easement confirm the parties agreement with respect to that portion. At the time the Agreement was signed, that portion was used for parking by the Cain building tenants and also for the location of storage sheds. See Exhibit 1. Thus, exclusive meant exclusive to Mr. Cain and no one else, including Mr. Cimino. But the facts and circumstances surrounding the southern portion of the easement are far different. Because Mr. Cains tow pen blocks access from Ranch Road to his two story house, the easement is critical to him and his tenants for such access, including access to the parking area in the eastern portion of the easement. He has no other true need, other than access, for that part of the easement (the southern part). It does not provide a buffer of any type, [Note 17] and must be kept open at all times for use by Mr. Cains tow trucks and to get to and from the parking spaces on the eastern side of the building.

For his part, Mr. Cimino needs access through the easement to offload vehicles bringing cars to his lot and for moving and positioning that inventory of cars around the lot. This is not a frequent or continuous use (cars are not offloaded or moved every day in this location), but it is critically important on those occasions when it is needed. Mr. Cain contends that Mr. Cimino can offload and position by keeping other areas of his lot open. But this overlooks the unique location of this portion of the easement, along or near the edge of a row of inventoried cars which need the easement to get there and back, and the fact that Mr. Cimino wants to expand his inventory, using his lot to its maximum extent. [Note 18]

Mr. Cain supports his interpretation of exclusive (excluding even Mr. Cimino) by pointing to the $400,000 reduction in sale price [Note 19] and the grant of a right of first refusal to Mr. Cimino to purchase the Ranch Road lot if the Cains decided to put it up for sale. This, he says, is consideration of such size that only one reasonable conclusion can be drawnit was done in return for Mr. Cains exclusive use and possession of the entirety of the easement. But that does not follow. There is nothing in the Agreement that allocates any particular consideration to the easement and, as noted above, I find the price reduction and right of first refusal to be terms the parties agreed-to as part of the overall deal, not in return for any specific provision.

Importantly, Mr. Cain had been in the car dealership business himself and well understood the importance of maintaining space for inventory on the lot. He also knew that Mr. Cimino wanted to grow his business and not just continue a used car dealership. Mr. Cimino invested substantial money into improving the dealership premises and eventually obtained a Mitsubishi franchise. I do not find it credible that, since Mr. Cimino was well into the process of building his business, he effectively would cede a significant portion of his dealership lot to Mr. Cain and agree to exclude himself from using his own property.

On Mr. Cains part, achieving access to the Ranch Road property was the crucial goal at the time the Agreement was made. The parties had been involved in prior disputes and lawsuits over access issues and the Agreement, negotiated over several months by the parties, addressed Mr. Cains concerns about access to his Ranch Road property. This is confirmed by two separate sections in the Agreement, designed to ensure Mr. Cains access rights. Paragraph 9(C) concerns access while Mr. Cain and FFC continued to occupy a portion of the dealership building post-closing, stating,

During said occupancy period of the premises by FFC [Cain], PR356/Cimino shall allow unrestricted access to the rental area by FFC [Cain], and shall not block any entrances, exits and/or parking area that may be used by FFC [Cain] to access the area occupied by FFC [Cain], including Gardner Street, also known as Ranch Road and any land owned by PR356 [Cimino] that would be used by FFC [Cain] to reach the leased areas.

Agreement at ¶ 9(C) (March 24, 2010) (Trial Ex. 9). Paragraph 11 concerns access once Mr. Cain and FFC had left the dealership property, stating,

As part of this Agreement, Cimino/PR356 agree not to inhibit and/or block any access to the FFC [Cain] property at 10 Ranch Road, or any property owned by PR356 [Cimino] and occupied by FFC [Cain] as may be allowed by the terms and conditions of this Agreement. Cimino/PR356 specifically agree not to block access to any properties owned by or used by FFC [Cain] as contemplated by this Agreement, including access as may be required through Gardner Road (Ranch Road) and/or Main Street.

Id. at ¶ 11. Since these sections were intended to protect Mr. Cains access, there is little evidence to support Mr. Cains contention that the parties intended to go one step further and prohibit Mr. Cimino from using the southern portion of easement area altogether. If the parties actually intended to vary the well-established rule that a servient owner may use his property in any manner consistent with the rights of the easement holder, that intention should have been clearly defined in the Agreement, or at least would have been the subject of some discussion among the parties, but there was none. If the parties truly agreed that Mr. Cain could totally exclude Mr. Cimino from all use of the easement, the language would have said exclusive access, use and possession.

But use of the easement by Mr. Cimino does not mean that his tenants have the same rights. As the evidence shows, the parties never intended any third-party tenants of Mr. Cimino to have any right to use the easement area. [Note 20] The word exclusive loses all meaning if that were so. Moreover, the attendant circumstances lead to the same conclusion. Mr. Cain had significant experience in the car dealership business, both as an owner and then as landlord to Mr. Cimino, and well understood the need and extent to which Mr. Cimino might use the easement area to offload or position his dealership car inventory. This was a known condition, and thus agreeable. But Mr. Cain had no such familiarity with any tenants Mr. Cimino might choose to have in his (Ciminos) building (there were none at the time the Agreement was signed). Mr. Cain could not know, for example, who Mr. Ciminos tenants might be at any given time, what their business might be, what their hours of operation might be, nor what impact their operations might have on the use of his building if they used the easement for access or any other purpose. In short, unlike the car dealership, they were an unknown quantity. They were thus excluded from the easement entirely.

It is precisely because Mr. Cimino has control over his tenants that I reject his contention that their ability to use the easement is somehow essential to his business interests, and thus that he would never have intended their exclusion from the easement. To begin with, he agreed to the word exclusive, and his own attorney knew that meant the exclusion of tenants and other third parties. See n. 20. For the reasons noted above, Mr. Cimino certainly knew that Mr. Cain would be opposed to tenant use of any part of the easement, and at the least might well have demanded veto power over their selection. Given the animosity in their relationship, Mr. Cimino quite clearly avoided pressing the issue. If tenant use was important to Mr. Cimino, the burden was on him to have the easement worded to allow it. As noted above, exclusive loses all meaning otherwise. [Note 21]

There is also no need (and certainly none that Mr. Cimino articulated at the time of the Agreement) for Mr. Ciminos tenants to use the easement. They can access the back portion of the dealership building from the Main Street entrance along the side of the building. See Ex. 1. Mr. Cimono argues that this will negatively impact his business (and thus, he says, he never agreed to it) because his grittier tenants, which include a landscaping and welding business, will be driving past his customers in the main showroom area. I find this concern an afterthought, and unpersuasive for the following reasons. First, Mr. Cimino never raised any such issue during the negotiations nor sought to insert such language in the Agreement. He is not a shy man, and would not have hesitated to do so if it was something he wanted. Second, he is the landlord. If he believes his tenants will harm his business, he can choose different tenants. Or he can restrict his tenants use of the Main Street entrance to times during the day that would not disturb his dealership business. Finally, if Mr. Ciminos tenants access their space from the Main Street entrance, their use will be transitory; they will not be lingering in front of the dealership. Simply put, this objection by Mr. Cimino rings hollow.

Plaintiffs Claims for Breach of Contract, Breach of the Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing, and G.L. c. 93A, §11 Violations

As an alternative to enforcing the contract under his interpretation of exclusive, Mr. Cain seeks damages in the amount of $400,000, which he alleges was the reduction in price he never would have agreed to if he did not get the sole right to use the entirety of the easement. As discussed above, the $400,000 price reduction was not connected to the grant of the easement and, in any event, the easement does not exclude use by Mr. Cimino and his dealership so long as that use does not interfere with Mr. Cains access. [Note 22] The easement agreement only excludes use by others, including Mr. Cimonos third-party tenants.

Mr. Cimino breached that aspect of the Agreement when he instructed his tenants to use the southern part of the easement for access to their space rather than the route they should have taken alongside his building. Mr. Cain is entitled to an injunction prohibiting all such use in the future. But as to the past use of the easement by those tenants, while improper, no actual damages were proved at trial. So far as the record shows, Mr. Cain has lost no rental income from the Ranch Road property. Indeed, he has had the same tenant since 2010. There was likewise no proof that Mr. Cains tow truck operations or tenants were blocked or impeded at any time by either Mr. Cimino or his tenants. Thus, no monetary damages are awarded.

I also find that Mr. Cain has failed to prove a violation of G.L. c. 93A, §11. To establish liability under §11, the so-called business-to-business provision of c. 93A, the plaintiff must show that the defendant engaged in an unfair method of competition or an unfair or deceptive act or practice. G.L. c. 93A, §11. [U]nfairness is determined from an examination of all the pertinent circumstances. Ordinarily a good faith dispute as to whether money is owed, or performance of some kind is due, is not the stuff of which a c. 93A claim is made. Northern Security Ins. Co. v. R.I. Realty Trust, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 691 , 696 (2011) (internal citations and quotations omitted). The inquiry focuses on the nature of challenged conduct and on the purpose and effect of that conduct as crucial factors in making a G.L. c. 93A fairness determination. Massachusetts Employers Ins. Exchange v. Propac-Mass, Inc., 420 Mass. 39 , 42-43 (1995). It is not the definition of an unfair act which controls but the contextthe circumstances to which that single definition is applied. Kattar v. Demoulas, 433 Mass. 1 , 14 (2000).

Here, both sides were assisted by capable counsel during all phases of negotiation. Yet, the language used in the Agreement remained ambiguous. In turn, both sides took an aggressive position on the meaning of the easement. Neither was entirely correct. Their differences have now been settled. Although Mr. Cimino breached the contract by allowing his tenants to use the easement, this did not go to the root of the contract. Petroangelo v. Pollard, 356 Mass. 696 , 701-02 (1970). Mr. Cain still got his easement allowing him access and parking. He suffered no actual damages from the use of the easement by Mr. Ciminos tenants. Furthermore, Mr. Ciminos position relative to the easements scope has been partially vindicated. With all ambiguities now resolved, any future violation by Mr. Cimino might well violate G.L. 93A, but it is not a violation now.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, and DECREED:

1. The plaintiffs, their tenants, customers, visitors, and suppliers and no one else may use the cross-hatched portion of the easement as shown on Exhibit 1 for access, parking, storage and structures.

2. The plaintiffs, their tenants, customers, visitors, and suppliers; and the defendants, their customers, visitors, and suppliers; may use the non-cross-hatched portion of the easement for access and egress only. No buildings, structures or parking are allowed in this area at any time except for temporary stops incident to travel. None of the defendants tenants, and none of those tenants visitors, customers or suppliers, may use any portion of the easement (cross-hatched or non-cross-hatched) at any time for any purpose.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

Having reviewed all the evidence, I find what truly was in the minds of the parties as they agreed upon the southern part of the easement and used the word exclusive was access by the occupants and visitors to the Cain property and such access as Mr. Ciminos regular car dealership operations might need from time to time, and the exclusion of everyone else.

FRED F. CAIN INC. and FRED F. CAIN v. 580 MAIN STREET WILMINGTON MA PR356 LLC and WILLIAM D. CIMINO

FRED F. CAIN INC. and FRED F. CAIN v. 580 MAIN STREET WILMINGTON MA PR356 LLC and WILLIAM D. CIMINO