Introduction

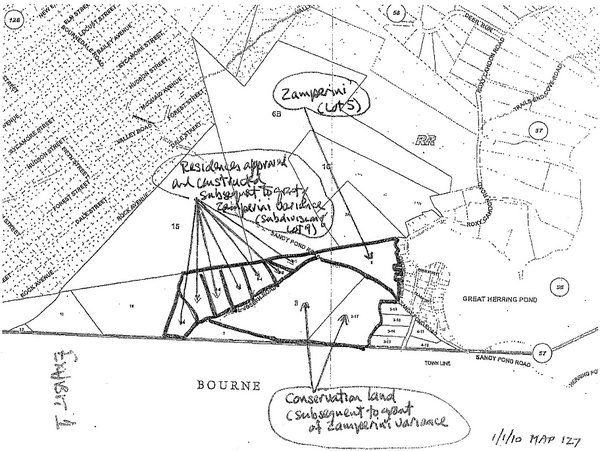

Plaintiffs John and Judi Zamperini own and live in a single family residence on a 7.6 acre parcel (Lot 5) on Sandy Pond Road/Sol Joseph Road in Plymouth (the road). [Note 1] They bought the then-vacant parcel in 1997, along with the abutting Lot 9, when the road (a private way) was relatively unimproved and, because of that, developments along it could only be built by variance from the zoning bylaws roadway requirements. The Zamperinis applied for such a variance for Lot 5, which was granted by the defendant Plymouth Zoning Board of Appeals subject to three conditions: first, the Zamperinis were required to improve the road by widening it to 16 feet and installing a compacted, 6-deep gravel base and surface, second, they were required to maintain the road in that condition, and third, they were prohibited from further subdividing Lot 5. Zoning Board of Appeals Decision, Case No. 2801 (Jul. 15, 1997). No reason was given for this third condition [Note 2] but, according to the Zoning Boards counsel in their briefs in this case, it was based on a concern about the density of future development along the road (at that time unknown) and the impact such density might have on road use. If so, that concern soon receded. By March 2000 the road improvements were in place, the Zamperinis built their home, and the Planning Board approved ANR plans for seven additional homes along the road. See Ex. 1, attached. Moreover, by April 2005, the Town had acquired the large parcels across the road and made them conservation land, removing the possibility they might ever be developed. Id. Lastly, by vote of Town Meeting, the zoning bylaw was changed and developments along such roads could now occur by special permit rather than variance.

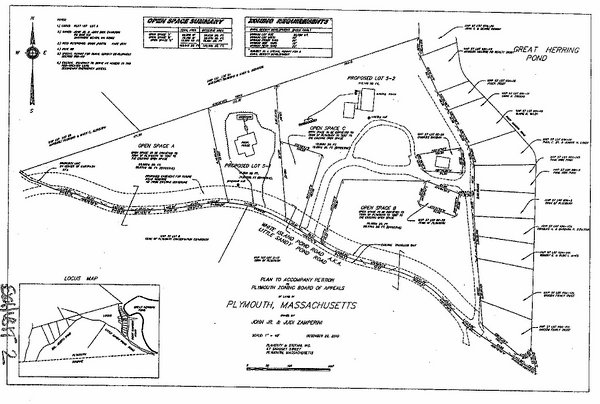

In October 2010, in accordance with that bylaw change, the Zamperinis applied to the Zoning Board for a special permit allowing them to create an additional building lot on their parcel. Included in their application was an associated request for the removal of the no subdivision condition in their 1997 variance. A copy of the Zamperinis plan, showing their existing home on Proposed Lot 5-2 and the proposed additional home on Proposed Lot 5-1, is attached as Ex. 2. The sole issue on both the special permit and variance modification requests was the adequacy of the road to support a new home on the subdivided lot. [Note 3]

The Planning Board reviewed the Zamperinis application and, by unanimous 5-0 vote, recommended its approval conditioned on the preservation of certain open space areas. [Note 4] The Zamperinis accepted those conditions and reflected them in their submission to the Zoning Board. See Ex. 2 (Open Spaces A, B & C, all to be conveyed to the Town). By 3-2 vote, however, the Zoning Board rejected the Planning Boards recommendation and denied the Zamperinis application in its entirety. The Zamperinis then timely filed this G.L. c. 40A, §17 appeal, contending that the Boards denial was arbitrary and capricious. The Board contends that it acted within its allowable discretion.

The matter was tried before me, case-stated, on agreed facts and exhibits. At the parties request I also took a view. As more fully set forth below, based on the parties Statement of Agreed Facts, the agreed exhibits, my observations at the view, and the inferences I draw from that evidence, I find and rule that the Zoning Board acted arbitrarily and capriciously in denying the Zamperinis application. The decision is VACATED and the matter is remanded to the Board to issue the special permit and modify the conditions of the 1997 variance as set forth below.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

In 1997, the Zamperinis acquired two vacant lots, Lot 5 and Lot 9, which front on Sandy Pond/Sol Joseph Road. At the time the Zamperinis acquired these lots, §300.05 of the Plymouth Zoning Bylaw provided for minimum access requirements that had to be satisfied before an owner could develop property. These were:

* The width of the traveled way [was] sufficient to allow two vehicles traveling in opposite directions to pass by one another (a minimum of 16 ft.) and to allow for snowplowing of the minimum width.

* The width of the existing right of way [was] at least 40 ft. in residential zones [,] or existing topography and existing or proposed structures allow[ed] for a right-of-way of at least 40 ft. to include eventual widening of the road and installation of sidewalks.

* The construction of the existing traveled way [was of] compacted binding gravel or better, such as to allow standard vehicles such as police cars, fire trucks, and ambulances to travel the road.

* The existing construction of the way [did] not allow or create any drainage problems either in the way, or adjacent street or ways, or on adjacent properties, and the Board determine[ed] that the road [was] not subject to the periodic flooding which makes it impassable, based on either historical documentation or inspection.

* The grade of the existing traveled way [did] not generally exceed 10% or exceed 15% in a few extreme instances.

* Dead end ways [had] existing turn-arounds of a least 60 ft., minimum radius and [did] not exceed 500 ft. in length.

Bylaw, §300.05.

The road failed to meet these requirements in two respects. It was not sufficiently wide, and it was not constructed of compacted binding gravel or better. [Note 5] Accordingly, in June 1997, the Zamperinis applied for a variance so they could build a single-family home on Lot 5. In July 1997, the Zoning Board granted the variance, conditioned on the Zamperinis widening the road to a minimum of 16 feet, giving it a base and surface of at least 6 inches of binding gravel, and maintaining it to that standard thereafter. As previously noted, the variance also prohibited further subdivision of Lot 5. Zoning Board of Appeals Decision, Case No. 2801 (Jul. 15, 1997).

The Zamperinis did not appeal any of these conditions. They improved the road as directed and subsequently constructed a single-family home on Lot 5, where they currently reside. The roadway remains in full compliance with the variance conditions, and both the Planning Board and Zoning Board have so found. [Note 6]

In 1999, the Zamperinis sold Lot 9 to Roger Zoebisch and Christopher Cummings. Mr. Zoebisch and Mr. Cummings submitted Approval Not Required (ANR) plans to the Planning Board, proposing to divide Lot 9 into seven, single-family lots and contending that the road met all of the requirements of §300.05. The Planning Board rejected these plans and Mr. Zoebisch and Mr. Cummings appealed that rejection to the Land Court. In connection with their motion for summary judgment, Mr. Zoebisch and Mr. Cummings submitted an affidavit from professional land surveyor Russell Stefani demonstrating that the road was fully compliant with the access requirements of §300.05. The Planning Board never contested that affidavit and, instead, agreed to settle the case with a remand and subsequent approval of the ANR plans, which was done. Mr. Zoebisch and Mr. Cummings then divided Lot 9 in accordance with those plans and, in 2000, built seven large single-family homes along the road, just past the Zamperini residence. See Ex. 1.

In light of these ANR approvals, in September 2001 the Zamperinis applied for a modification of their variance to remove the condition prohibiting subdivision of Lot 5 so that they could divide that lot and build an additional single-family home on the newly subdivided part. In connection with that application, they submitted a slightly modified version of Mr. Stefanis affidavit, which again demonstrated that the road complied with the minimum access requirements of §300.05 of the zoning bylaw. In November 2001, the Zoning Board denied their request to remove the condition, ruling that it was, in effect, a request for a new variance and finding that the Zamperinis had not met the criteria for such a variance. See Zoning Board of Appeals Decision, Case No. 3062 (Nov. 15, 2001). Again, the correctness of that Decision was never tested since no appeal was taken.

In 2003, the Town replaced §300.05 of the zoning bylaw with §205-17E, which allows property owners to apply for a special permit, instead of a variance, to develop lots on roads that do not meet the bylaws by right criteria. In making this change, the Town recognized that the standards for granting a variance are extremely onerous and adopted the new bylaw to bring more flexibility to access petitions and implement a more equitable process for property owners to improve substandard ways. See Trial Ex. 22, Final Report and Recommendation of the Planning Board on the Proposed Amendment to the Zoning Bylaw Section 300.05 Uses to Have Access at 5 (Jan. 21, 2003). Under the new bylaw, in the situation presented by this case (a private way not previously approved by the Planning Board under the Subdivision Control Law), a road must meet the following requirements for a home to be built by right:

* The width of the improved travel way [must be] sufficient to serve the proposed use as well as the existing uses. In no case shall the improved traveled way be less than 16 feet in width.

* The width of the existing road layout or easement [must be] at least 40 feet.

* The construction of the improved traveled way [must be] sufficient to serve the proposed use as well as the existing uses. The minimum acceptable construction standard [must] consist of compacted binding gravel consisting of crushed asphalt pavement, crushed cement concrete or gravel borrow meeting the Massachusetts Highway Department Standard Specifications for Highways and Bridges, Sections M1.03.0 and M1.11.0.

* No drainage problems [must] exist in the way, on adjacent ways or on adjacent properties.

* Based on historical documentation or inspection, the road [must not be] subject to periodic flooding, making it impassable.

* The grade of the existing improved traveled way [must] not exceed 10%.

* Dead-end ways [must have] improved turnarounds of a least 60 feet minimum radius and [must] not exceed 500 feet in length.

§205-17E (2)(c) [1]-[7].

If the road fails to meet these requirements, development may still occur by special permit from the Zoning Board of Appeals so long as the following conditions are met:

* The width of the improved traveled way is sufficient to serve the proposed use as well as the existing uses.

* The width of the layout or easement is sufficient to serve the proposed use as well as the existing use.

* The construction of the improved traveled way [will] be sufficient to serve the proposed use as well as the existing.

* No drainage problems will exist or be created in the way, on adjacent ways or on adjacent properties.

* The road will not be subject to periodic flooding.

* The grade of the existing improved traveled way will not exceed 10%.

* Sufficient turnaround provisions are provided for emergency vehicles.

§205-17E (3)(b)[1]-[7]. [Note 7]

In 2010, based on the new bylaw, the Zamperinis applied for a special permit and a modification of their variance so they could divide their property and construct an additional single-family home. The Planning Board reviewed the Zamperinis plan and recommended its adoption by the Zoning Board, provided two conditions were met, first, that the Zamperinis developed a Rural Density Development plan approved by the Planning Board to preserve parts of Lot 5 as open space, [Note 8] and second, that a mechanism was provided for roadway improvement through the creation of a 40 foot wide roadway layout or easement that would allow for future improvements if needed. [Note 9]

The Zamperinis met both conditions, and embodied them in the RDD plan they submitted with their application to the Zoning Board. Ex. 2. Three separate sections of land (Open Spaces A, B and C), with a combined effective area of 120,038 square feet, would be conveyed to the Town as open space. For the 40 roadway layout or easement, the 16 traveled way was to remain as is (fulfilling the requirement of §205-17E (2)(c) [1]) and the remaining 24 would be more than met by the Zamperinis grant of an easement on an additional 32 of their land for any future widening deemed necessary, making 48 available in all. [Note 10] Id.

The Zamperinis submitted the RDD plan to the Zoning Board in December 2010 as part of their application. Rejecting the Planning Boards recommendation of approval, the Zoning Board denied the Zamperinis application, giving the following as its reasons:

(1) the road was not sufficiently wide to accommodate a new home in addition to the homes that already existed along the road;

(2) the present roadway layout, less than 40 feet in width, was not sufficiently wide to serve an additional home as well as the existing homes;

(3) the application did not propose improvements to the width or condition of the road;

(4) the condition in the original variance prohibiting subdivision of Lot 5 was reasonably intended to limit development in a remote area with limited access;

(5) the circumstances related to the impact of additional development in this area had not changed significantly since the variance was granted in 1997;

(6) the original variance had never been appealed;

(7) the condition in that variance prohibiting further subdivision of Lot 5 had been acceptable to the Zamperinis at that time;

(8) the variance had been exercised, and the Zamperinis constructed their home based on its condition; and

(9) the road did not comply with Fire Department recommendations for an emergency vehicle turning radius of 50 feet.

Zoning Board of Appeals Decision, Case No. 3610 (Jan. 18, 2011).

The Zamperinis then timely appealed that decision to this court.

The court took a view of the road as part of the trial in this case, confirming the roads width (16-18), its condition (a flat, well-compacted, graveled surface with no apparent drainage, sight-line, or other issues), and observing its lack of traffic. During the half-hour view taken mid-morning on a Saturday in early September, not a single vehicle was observed using the road and there were neither ruts nor other evidence indicating any significant use. The view also included the location of the proposed 40 easement (40 north of the centerline), which I find is fully capable of use, and could actually and practicably be used, for road-widening at any time. [Note 11]

Further facts are contained in the Discussion section below.

Discussion

The applicable standard of review has been recently summarized by the Supreme Judicial Court as follows:

Judicial review of a local zoning boards denial of a special permit involves a combination of de novo and deferential analyses. The trial judge makes his own findings of facts and need not give weight to those the board has found. The judge then determines the content and meaning of statutes and bylaws and decides whether the board has chosen from those sources the proper criteria and standards to use in deciding to grant or to deny the variance or special permit application. We accord deference to a local boards reasonable interpretation of its own zoning bylaw, with the caveat that an incorrect interpretation of a statute is not entitled to deference.

After determining the facts and clarifying the appropriate legal standards, the judge determines whether the board has applied those standards in an unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary manner. This stage of judicial review involves a highly deferential bow to local control over community planning. The board is entitled to deny a permit even if the facts found by the court would support its issuance. The judge nonetheless should overturn a boards decision when no rational view of the facts the court has found supports the boards conclusion. Deference is not appropriate when the reasons given by the board lacked substantial basis in fact and were in reality mere pretexts for arbitrary action or veils for reasons not related to the purposes of the zoning law.

Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership v. Board of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 474-475 (2012) (internal quotations and citations omitted).

The analysis thus begins with the proper interpretation (the content and meaning) of Bylaw §205-17E, and whether it was correctly applied by the Board.

As the Boards 2001 Decision concedes, the road met the requirements of former Bylaw §300.05 at that time. Zoning Board of Appeals Decision, Case No. 3062 (Nov. 15, 2001) at 1 (Sandy Pond Road is a private way that complies with the minimum access standards of Section 300.05 of the Zoning Bylaw), 5 (The roadway meets all requirements of the Zoning Bylaw). The Board contends that the new §205-17E changed those requirements in certain respects, and then argues that the changes justify the Boards present rejection of the adequacy of the road. I disagree.

§300.05 permitted an applicant to submit a plan showing either (1) an existing 40 foot wide right of way, or (2) existing topography and existing or proposed structures [that would] allow for a right-of-way of at least 40 ft. to include eventual widening of the road

. The Zamperinis did the latter, and the Zoning Boards and Planning Boards previous decisions confirm that the existing topography and structures allow the usage of the full 40 feet if needed. See n. 6, supra. The new bylaw, §205-17E(2)(c)[2], provides that [t]he width of the existing road layout or easement shall be at least 40 feet. The Board thus argues that the standard has changed. In its view, while the prior bylaw allowed for a determination that the 40-foot width could be met in the future, the Board contends that new bylaw requires that a 40-foot wide road layout or easement already exist and, since it did not, the Zamperinis application was properly rejected. This is an incorrect reading of the bylaw. Where, as here, (1) the application contains the tender of such an easement, (2) the easement is capable of use, and (3) the allowance of the special permit application and/or the issuance of the building permit can be conditioned on the easements grant, the bylaw requirement has been met.

Bylaws are interpreted in accordance with the familiar rules of statutory construction. See Shirley Wayside Ltd. Partnership, 461 Mass. at 477. The bylaws language should be given effect consistent with its plain meaning and in light of the aim of the Legislature [here, Town Meeting] unless to do so would achieve an illogical result. See Commonwealth v. George W. Prescott Publishing Co., 463 Mass. 258 , 264 (2012) (citation omitted). Courts establish the intent of the bylaw from all its parts and from the subject matter to which it relates, and interpret it so as to render the legislation effective, consonant with reason and common sense. Id. Here, the bylaw was changed to bring flexibility when dealing with access petitions, provide a more equitable process, and give the Board the ability to consider the impacts of existing traffic conditions when reviewing requests for building permits on substandard ways. Trial Ex. 22, Final Report and Recommendation of the Planning Board on the Proposed Amendment to the Zoning Bylaw Section 300.05Uses to Have Access at 5-6 (Jan. 21, 2003). The interpretation of §205-17 now advanced by the Zoning Board, making compliance with the bylaw less flexible, is inconsistent with this. It is also inconsistent with the bylaws purpose of allowing improvements to substandard roads, which surely includes the provision of additional right-of-way. Contrary to the Boards argument, existing is not limited to on the ground, now. It can also mean by grant, effective at the time the building permit is issued, which is the logical, most consistent, and thus correct, interpretation.

The Zoning Boards Denial of the Zamperinis Application for a Special Permit and Modification of Their Variance was Arbitrary and Capricious

A Boards decision to refuse to modify a condition of a variance may be found to be arbitrary and capricious when a plaintiff has demonstrated that circumstances affecting the property have changed since the variance was granted, and the Boards reasons for denying the modification are unsupported by the facts. See Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers, 454 Mass. at 384-86. A refusal to grant a special permit may also be overturned when unsupported by any rational view of the facts. Id.

Since the Zamperinis first obtained their variance in 1997, I find and rule that circumstances affecting their property have changed in three significant respects.

First, the subdivision of Lot 9 and subsequent construction of seven homes along the road constitutes a change of circumstances that supports the Zamperinis variance request. The addition of these seven homes since the original variance was granted in 1997 demonstrates that the Boards concerns about the adequacy of the road have not materialized. There was no evidence that there have been any problems with access or emergency service along the road, and none to show that one additional home will be any kind of tipping point. Continuing to cite adequacy of access as a reason for refusing to modify the variance condition is unreasonable and simply not supported by the ten years of continuous use of this road without issue. It is also inconsistent with the granting of permits to build these seven new homes. Based on the evidence in the record and my observations at the view, I find that adding one single family home to the eight that now exist will not make any material difference to road usage and adequacy. Fire trucks, emergency vehicles and police cars will use it the same way they use it to access the seven new homes and a ninth home adds no new material risks requiring service nor any material traffic increase.

Second, in the years since the Zamperinis first request to modify their variance was turned down in 2001 for failing to meet the standard for a variance, the Town has voted to move away from that standard, choosing instead to adopt the less onerous standard for a special permit. Having previously been denied relief under the variance standard, this change in Town policy, intended to be more favorable to property owners like the Zamperinis, cuts in favor of their present application.

Lastly, in the years since the Board granted the variance to the Zamperinis, the Town has acquired parcels directly to the south of the Zamperinis lot for conservation as open space. The acquisition of this conservation land necessarily guarantees that development along this road in the future will be limited and thus alleviates the need for keeping in place the restriction on the Zamperinis ability to divide their lot. Furthermore, the Zamperinis RDD plan further limits development along Sandy Pond Road by conveying three separate tracts of Lot 5 to the Town for preservation as open space.

In addition to these changed circumstances, I find and rule that the Zoning Boards reasons for refusing to grant a special permit and modify the 1997 variance lack a substantial basis in fact and are thus unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary. Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers, 454 Mass. at 386 (internal quotations and citations omitted). The Zoning Board listed nine reasons for its decision. I briefly address each in turn.

As its first and second reasons, the Zoning Board found that the width of the traveled way along Sandy Pond Road was insufficient to serve an additional home as well as the existing homes, and the width of the road layout was less than 40 feet wide. As described above, these reasons lack factual support and are based on an incorrect interpretation of §205-17E. The road has accommodated eight homes for the last ten years without issue. Use of the road by residents of one additional house will not jeopardize access. And should future widening be needed, the Zamperinis RDD plan provides for a 40-foot wide easement (48 in total) to make those improvements.

Third, the Board noted that the Zamperinis had not proposed any additional improvements to the width or construction of the traveled way. This is plainly at odds with the RDD plan submitted by the Zamperinis in connection with their application. As noted above, that plan (and its associated offer) show a 40-foot wide easement extending to the north from the centerline of the road available for any future road widening deemed necessary.

As its fourth and fifth reasons, the Board stated that limitation of further development was a reasonable condition of the original variance and circumstances relating to impacts of additional development had not changed. But since 1997, the Town has been able to limit development through the acquisition of open space parcels to the south of the Zamperinis lot. Simply put, the Boards professed concern about the construction of one additional home on the Zamperinis lot is not based in fact.

The Boards sixth, seventh, and eighth reasons can be summarized as follows: the Zamperinis were satisfied with the variance they obtained in 1997, they did not appeal the variance, and they eventually exercised that variance. While all of these statements are true, they do not constitute a legal basis for denying the Zamperinis request when circumstances justifying the conditions of the original variance have changed significantly. See Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers, 454 Mass. at 383-84 (rejecting board of appeals argument that property owner was estopped from appealing variance condition five years later after circumstances affecting property had changed significantly).

The Boards final reason was that the ways serving the lot do not comply with the Fire Departments recommended emergency vehicle turning radius of 50 feet and have a width of less than 22 feet. These figures come from a memo provided to the Board by the Chief of the Fire Department. The memo, however, does not cite any specific fire department regulations and at trial the Board could only say that the figures reflect the fire chiefs own opinion. Sandy Pond/Sol Joseph Road is not a dead end street and the Boards decision fails to articulate any reasons why a 50 foot turning radius is required. Again, this road has provided access for the Zamperinis and its many other homes for over ten years without impeding emergency vehicles. Finally, the Boards decision overlooks the fact that the Zamperinis RDD plan provides for a 40 foot wide easement to allow for future road widening if needed.

Relief

Although, in the ordinary course, courts are reluctant to order boards to grant relief, such an order is appropriate where remand is futile or would postpone an inevitable result. Wendys Old Fashioned Hamburgers, 454 Mass. at 388. The Board has considered the Zamperinis request to allow them to build an additional house on two separate occasions, and both times the Boards denial failed to include facts that adequately support its conclusions. The Boards decision regarding the adequacy of the road to accommodate an additional home is at odds with both the conclusions of the Planning Board, the facts of this case as set forth above, and my observations of the road during the view. Remand to the Zoning Board to consider the Zamperinis request for a third time would simply delay an inevitable result. Thus, an order directing the Board to enter the particular relief sought once an RDD plan is approved by the Planning Board is warranted.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Boards decision denying the Zamperinis application for a special permit and variance modification is REVERSED. Once the Planning Board approves an RDD plan, the Board is hereby ORDERED to issue a special permit for roadway improvements under §205-17(E)(3)(b) and remove the condition against further subdivision of Lot 5 from the 1997 variance (Case No. 2801) subject to the Zamperinis grant of the 40 easement shown on Exhibit 2.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

JOHN ZAMPERINI, JR. and JUDI ZAMPERINI v. PETER CONNOR, DAVID PECK, WILLIAM KEOHAN, MICHAEL MAIN and EDWARD CONROY as members of the PLYMOUTH ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS.

JOHN ZAMPERINI, JR. and JUDI ZAMPERINI v. PETER CONNOR, DAVID PECK, WILLIAM KEOHAN, MICHAEL MAIN and EDWARD CONROY as members of the PLYMOUTH ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS.