Introduction

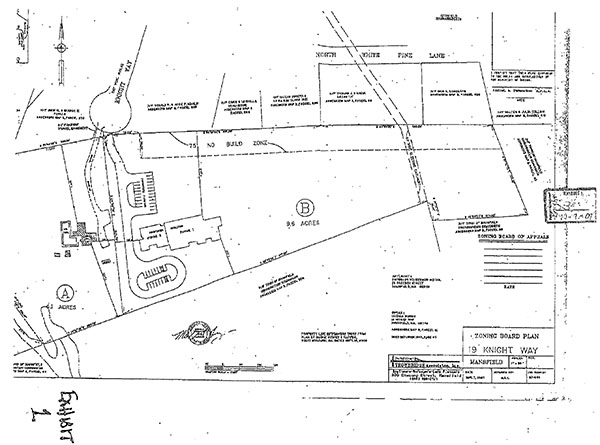

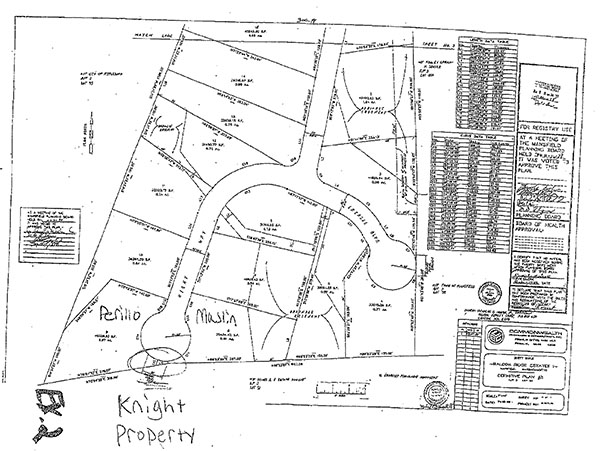

This case is a dispute over the existence and scope of an alleged 50-wide easement over the property of plaintiffs John and Sharon Perillo and Gerald and Anne Maslin, benefiting the property of defendant Brenda Knight at 19 Knight Way in Mansfield. The Knight property consists of over 13 acres, is currently occupied by a single family home, and is the site of a proposed Montessori school. The easement is at its entryway, half on the Perillos property to the west and half on the Maslin to the east. See Ex. 1. The Perillo and Maslin properties are part of a subdivision called the Balcom Ridge Estates developed by Global Realty Trust in 1989, and the easement, as shown on the subdivision plan, is referenced in the Perillo and Maslin deeds. See Ex. 2.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the evidence received, my assessment of the credibility of that evidence, and the reasonable inferences I draw from the credible evidence, I find and rule as follows.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

This dispute arose when Ms. Knight, in conjunction with Hands On Montessori Elementary School Inc., proposed to build a one-story, 17,000 square foot school on her property (the Montessori School). The proposed school would be built opposite Ms. Knights residence and serve 160 children, 130 under the age of seven and 30 between the ages of seven and twelve. In order to build the school, Ms. Knight needs to make use of the 50-wide travel easement. See Ellsworth v. Town of Mansfield, Case No. 08 MISC 382311 (KCL), Memorandum and Order on the Parties Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment (July 25, 2011).

Ms. Knight, along with her late husband James, acquired the property in 1974. At the time the Knights purchased their property, it benefited from an express right of way and easement for a 12-wide road (1950 right of way) providing access to their property via Balcom Street, a public way. This express easement, sometimes called the Jewell Street Extension, was approximately a quarter-mile long and ran through the property now occupied by the Balcom Ridge Estates. This 1950 right of way was the only means of access to the Knight property.

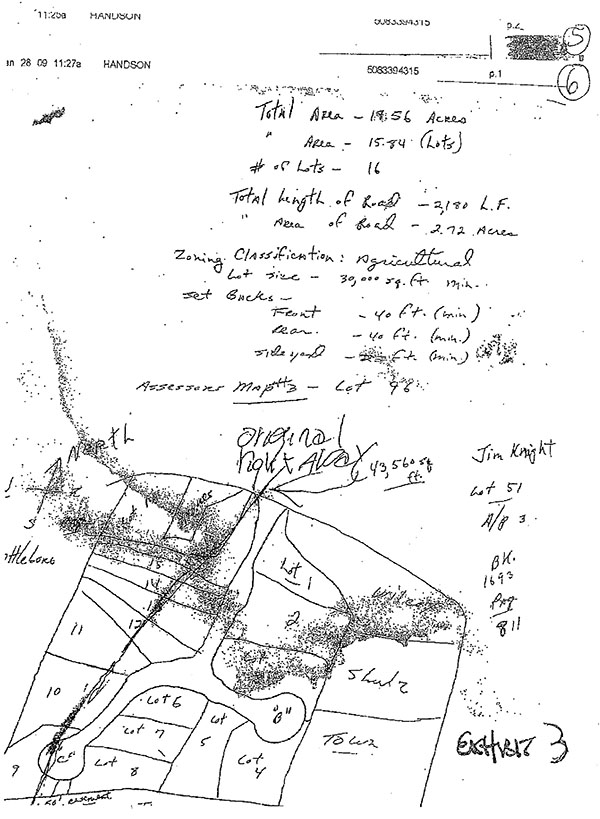

The easement in dispute in this case is a second easement, created as a result of the agreed elimination of the 1950 right of way. In 1989, the property now owned by the plaintiffs was owned by Global Realty Trust, which intended to develop it into a 16-lot subdivision. Global needed to eliminate the 1950 right of way benefiting the Knights property to free up enough space to make seven of its lots buildable. See Trial Trans. at 131-132 and Ex. 3 (contemporaneous sketch).

When Mr. Knight learned of the planned subdivision, he attended a Mansfield Planning Board meeting and expressed concern about the effect the subdivision might have on the access to his property. The Planning Board apparently shared Mr. Knight's concern, and advised Global to consider Mr. Knight's request for a new easement before submitting the subdivision plans for approval. See Mansfield Planning Board Meeting Minutes at 4 (May 18, 1988). Shortly thereafter, Nicholas Harris, the owner of Global, approached Mr. Knight to negotiate the elimination of the 1950 right of way. According to Mr. Harris, Mr. Knight insisted on obtaining a 50-wide right of way so that he could develop his property in the future. [Note 1] Mr. Harris agreed to the 50' right of way and incorporated it into the subdivision plan (1989 subdivision plan) as the 50' roadway travel easement. See Ex. 2. He then showed the plan to Mr. Knight and submitted it to the Mansfield Planning Board for approval. No formal grant of easement was ever drafted or signed.

The plans depicting the subdivision, its roads, and the 50'-wide travel easement were approved by the Mansfield Planning Board and recorded at the Registry of Deeds. See Ex. 2. The Perillos' deed references the 1989 subdivision plan for a more particular description of the granted premises. Deed, Woodie to Perillo (Aug. 31, 1999). The Maslins' deed contains a similar reference, describing their land as being as shown on the 1989 subdivision plan. Deed, The Rondo Company, Inc. to Maslin (Nov. 22, 1996). The roads created by the subdivision were later accepted by the town and became public. Order of Taking for Layout of Knight Way (Jun. 10 1989).

The 50 easement was not improved to its full width. Instead, the Knights continued to use a 25-long section of the pre-existing 12-wide easement that ran from the Knight Way cul-de-sac to their property. This 12-wide driveway was graveled and lies exclusively on the Perillos' property, entirely within the 50 easement.

For the past 16 years, both the Perillos and the Maslins have treated the land bordering the gravel driveway as lawn space, seeding and mowing it. The Knights have also mowed it, placed their mailbox there, and planted a few small trees near the western edge. None of the trees are of any appreciable size and can easily be moved or removed.

In 2007, Ms. Knight notified her neighbors that she planned to sell part of her property to Hands On Montessori Elementary School Inc., and use the full 50 width of the easement for access. The Perillos and Maslins claim that, despite the fact that their deeds reference the 1989 subdivision plan, they had no knowledge of the alleged 50-wide easement prior to this notice. They then brought this action seeking a declaration that the 50' travel easement does not exist. In the alternative, they seek a declaration that the easement was either abandoned or would be overburdened if used for access to the school, effectively barring its operation.

Further facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

Existence of the 50-Wide Easement

The plaintiffs contend that the 50-wide easement does not exist. I disagree.

The 50-wide roadway travel easement is an implied easement, created by recorded plan and deed reference without the need for a formal grant. The origin of an implied easement whether by grant or by reservation must be found in a presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable. Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006) (finding an implied easement through deed references to recorded subdivision plan and other circumstances) (internal citations and quotations omitted). Furthermore, [a] plan referred to in a deed becomes a part of the contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of the lots and to determine the rights intended to be conveyed. Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted).

Plaintiffs correctly note that Ms. Knight has the burden of proving that the easement exists. See Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 105 (1933) (The burden of proving the intent of the parties to create an easement . . . is upon the party asserting it.). I find that she has met that burden. The 1989 subdivision plan clearly delineates a 50-wide travel easement extending over the plaintiffs property. This plan was later referenced in the deeds of both plaintiffs as part of the description of their parcels. The inclusion of the 50-wide travel easement in the 1989 subdivision plan (Ex. 2) was the end result of a negotiation between Mr. Knight and Mr. Harris, in which the Knights agreed to the elimination of the 1950 right of way in exchange for the right to travel over the new subdivision roads and link them to his property via a 50-wide travel easement. The Planning Board heard and approved that request, and it was embodied in the approved definitive subdivision plan, duly recorded and referenced in the plaintiffs deeds.

The subdivision developer, Global Realty Trust, was more than willing to agree since the elimination of the former easement enabled it to create and sell seven additional lots. See Ex. 3

Plaintiffs base their argument almost exclusively on Patel v. Planning Bd. of North Andover, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 477 (1989). But, as noted in a previous ruling, Patel does not apply to this case. See Memorandum and Order on the Parties Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment at 5 (Jul. 28, 2011). As explained in that Memorandum, Patel presented two issues.

The first was whether the mere approval and recording of a subdivision plan which refers to a roadway

convey[s] an easement in favor either of those owning property abutting the subdivision or the public generally. 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 480. The court held no. Id. But that is not the case here. This was not a mere approval and recording of a plan. To the contrary, in return for giving up their existing easement, Ms. Knight and her late husband were given an explicit promise of both an easement over the subdivision roads and a 50-wide easement from those roads to their property the easement at issue in this lawsuit. That 50-wide easement was placed on the 1989 subdivision plan, and that plan, duly recorded with the easement clearly shown, was later referenced in the plaintiffs deeds as the explicit description or showing of their properties. The plaintiffs properties are thus burdened by the easement. See Reagan at 458 (A plan referred to in a deed becomes a part of the contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of the lots and to determine the rights intended to be conveyed.) (internal quotations and citations omitted).

The second issue in Patel was whether a reference to a subdivision plan in the deeds to the subdivision owners created an easement over the subdivision roads in favor of abutters or the public at large. Again, the court held no since the abutters and members of the public were strangers to the deed[s]. Patel, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 481. But again, that is not the issue presented in this case. The Knights were not strangers: (1) they gave up their existing easement to get this one, (2) the 50-wide easement was placed on the 1989 subdivision plan, and (3) that plan was incorporated into the plaintiffs deeds, (4) all as an integral part of the Knights agreement with the subdivision developer. See also Reagan, 446 Mass. at 458 (finding an implied easement through deed references to recorded subdivision plan and other circumstances). Thus, the plaintiffs reliance on Patel is misplaced.

The plaintiffs also contend that they had no knowledge of the easement prior to 2007. But this is not correct. The plaintiffs deeds expressly reference the 1989 subdivision plan which shows the easement and, indeed, their lots are described by reference to that plan. Furthermore, the existence of the Knights gravel driveway surely put the plaintiffs on notice that an easement of some type and dimension existed, and triggered an obligation of further inquiry.

Abandonment of the Easement by the Knights

Plaintiffs contend that, even if the 50-wide travel easement existed at some point in time, Ms. Knight abandoned it by acquiescing to the plaintiffs use of the land as lawn space and failing to assert her right to the easement for over 18 years.

Abandonment is a question of intent and can be proven by acts indicating an intention to never again make use of the easement. Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 592 (1965). The party asserting abandonment carries the burden of proof. New York Cent. R.R. Co. v. Swenson, 224 Mass. 88 , 92 (1916). Nonuse by itself does not prove abandonment. Cater v. Bednarek, 462 Mass. 523 , 528 (2012) (finding a valid easement in spite of a ninety-eight year period of nonuse by the dominant estate holder). In addition to nonuse, plaintiffs must show that the defendant took affirmative action showing either a present intent to relinquish the easement or a purpose inconsistent with its further existence. Lasell Coll. v. Leonard, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 390 (1992) (internal citation omitted). On this claim, the plaintiffs fall short. Although Ms. Knight did not assert her right to the 50-wide easement until 2007, she took no affirmative actions that show an intention to never make use of it. At the time it was created, the easement was not intended for immediate use. It was intended for the time when the Knights developed or subdivided their expansive property. This arose in 2007 when Ms. Knight decided to sell a portion of her property to the Montessori School. Even if the Perillos, Maslins, and Ms. Knight treated the area within the easement as lawn space, that use was not inconsistent with the continued existence of the easement. The few scattered trees in the easement area were planted by the Knights for decorative purposes and can easily be moved or cut down. The mailbox can also easily be moved. Therefore, the assertion that Ms. Knight intended to abandon the easement fails.

Overburdening

The plaintiffs final contention is that the proposed use of the Knight property for a school will overburden the 50-wide travel easement. Since Ms. Knight is relying upon the easement, the burden is on her to show that the proposed use is consistent with the scope of the easement. Swenson v. Marino, 306 Mass. 582 , 583 (1940). The question, put simply, is whether the traffic generated by the school was contemplated by the parties at the time the easement was created, bearing in mind that full development of the 13 acres was clearly anticipated.

Traffic impact is a matter of expert testimony. Hilltop Gardens Inv., LLC v. JMK Dev., LLC, 13 LCR 202 , 206 (2005) and cases cited therein. Neither side provided the court with expert testimony concerning the traffic impact of the proposed use of the easement. [Note 2] Also, the school has not been built and may be modified before then. It is also uncertain what types of traffic it might generate (cars only? school buses?), how numerous the vehicles might be, and at what hours the vehicles will use the easement. It is thus premature to rule on the overburdening question at this time, and I decline to do so. The challenge may be raised in another lawsuit.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the 50-wide easement at issue in this case exists, has not been abandoned, and its full width may be used to access the defendants property. I have not and do not rule on whether any potential future use of the easement for the Montessori School will overburden. Such a claim, once ripe and if timely brought, may be addressed in another proceeding.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

JOHN PERILLO, SHARON PERILLO, GERALD MASLIN and ANNE MASLIN v. BRENDA KNIGHT.

JOHN PERILLO, SHARON PERILLO, GERALD MASLIN and ANNE MASLIN v. BRENDA KNIGHT.