Introduction

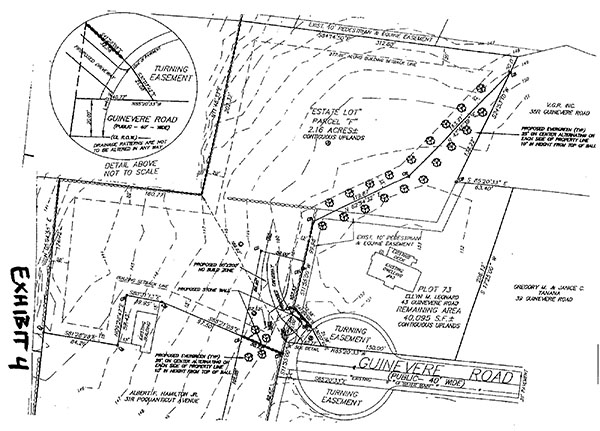

On March 12, 2008, [Note 1] the Easton Planning and Zoning Board approved defendant Aaron Wlukas application for a special permit allowing the creation of an Estate Lot [Note 2] on land owned by Ms. Ellyn Leonard, directly abutting a 2.11 acre vacant parcel owned by plaintiff V.G.R. Northeast Inc. See Ex. 4. This case is VGRs G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal of that permit.

Mr. Wluka has moved to dismiss VGRs appeal for lack of standing. After initially claiming standing based on an alleged decrease in the value of its property, increased storm water runoff, and interference with its rights to use a 10 foot wide pedestrian and equine easement, VGR has since withdrawn the first two contentions and now relies solely on the third the alleged interference with its easement rights to give it standing to bring this case.

Should standing be found, another set of motions comes into play. These are the parties cross-motions for summary judgment on the issue of whether the Board properly concluded that Mr. Wlukas proposed Estate Lot meets the 40 foot frontage requirement in the bylaw. [Note 3] VGR contends that it does not, arguing that (1) Guinevere Road (the road on which frontage is claimed) cannot be used as frontage because it never became a public way, (2) even if Guinevere Road can be used as frontage, Mr. Wluka improperly calculated that frontage by measuring horizontally along the boundary between his lot and Guinevere Road as shown on the approved subdivision plan (a distance of 40.77 feet, see Ex. 4) instead of around the arc of its cul-de-sac, and (3) since Guinevere Road currently terminates at the western edge of the cul-de-sac rather than the edge of the abutting property, Mr. Wluka improperly included the 20 feet between the edge of the cul-de-sac and the abutting property in his frontage measurement in order to meet the 40 foot requirement. See Exs. 2 and 4.

For the reasons set forth below, VGRs complaint is DISMISSED for lack of standing. Moreover, even if VGR had standing and the merits of its claims were reached, those claims would still be dismissed and the permit upheld.

Facts

The following facts are not in genuine dispute.

VGR is a Massachusetts corporation whose purpose is to engage in the business of purchasing, selling and distributing, at wholesale or retail, and in every other manner, janitorial, cleaning and building maintenance supplies of every kind and character, and all equipment, goods and materials of every kind and character used in connection thereto and also to engage in all other business or activities that are lawful under the laws of Massachusetts. VGR Articles of Incorporation. Mr. James Antosca is VGRs president.

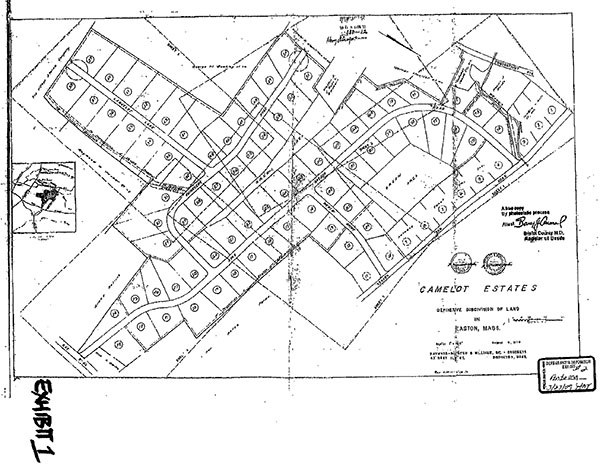

In August 1970, Mr. Antosca was the president of Antosca Construction Co., Inc., which obtained approval of a definitive subdivision plan for Camelot Estates. See Ex. 1.

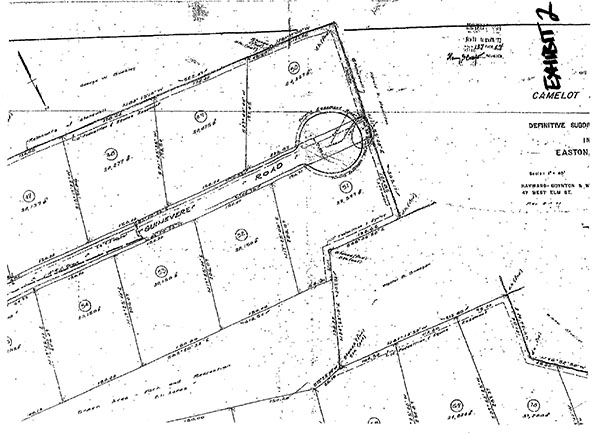

The subdivision created four new roads, Lancelot Lane, Guinevere Road, King Arthur Road, and Merlin Drive, as well as a 10-wide pedestrian and equine easement around its borders. Id. As shown on the subdivision plans, Guinevere Road is 40 wide and extends to the edge of the abutting property. See Exs. 1 (entire subdivision) and 2 (blow-up of relevant portion of Guinevere Road and the properties at issue in this case). Guinevere Road also has circular turning easements on its northern and southern sides, twenty feet back from the abutting property boundary, so that its overall appearance is that of a cul-de-sac. Id. As constructed, it currently terminates at the cul-de-sac, twenty feet from the subdivision boundary. Id.

In March 1973, Antosca Construction conveyed the lots along Guinevere Road, along with other lots, to the Center Realty Trust. The deed specified that the lots were conveyed [t]ogether with the fee in the streets and roads shown on the above mentioned plans. In August 1974, Center Realty conveyed those lots to Camelot Estates Corp., again including the fee to the streets and roads shown on the subdivision plans.

Between 1975 and 1978, Camelot Estates Corp. sold the lots along Guinevere Road to the public. The deeds specified that [t]he granted premises are conveyed together with the fee and soil of the ways shown on the plan showing the granted premises which is referred to in the description thereof to the centerline of said ways insofar as the same adjoin the granted premises.

In May 1978, Camelot Estates Corp. conveyed a number of lots along Lancelot Lane, King Arthur Road and Merlin Drive to Easton One Corp. This conveyance similarly included language that it included the fee in the roads and streets as shown on the above mentioned plans. In June 1982, Easton One Corp. conveyed the triangular-shaped 2.11 acre parcel labeled Green Area on Ex. 1 [Note 4] to Antosca Construction along with the fee in all roads and streets shown on the above mentioned definitive subdivision plans.

In November 1990, Antosca Construction conveyed its interest in Lancelot Lane to the Town of Easton along with all of the grantors right title, interest and estate in and to all of the roadway right of ways, including those two certain semi circular areas at the end of Guinevere Road shown on the subdivision plans. It conveyed the 2.11 acre parcel to VGR in 1997. This deed once again included the fee in all roads and streets shown on the above mentioned plans.

VGRs lot (the 2.11 acre parcel, still vacant) cannot be accessed by any of the roads in the subdivision. Instead, it has access only by way of the 10 foot wide pedestrian and equine easement, specifically the portion of that easement that runs along the western and northern boundaries of Lot 51. See Ex. 2.

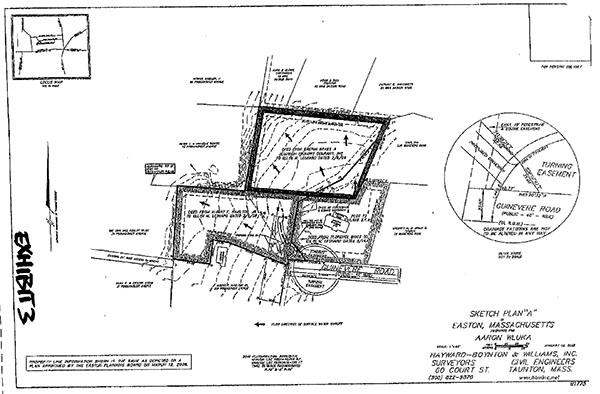

Ms. Ellyn Leonard owns Lot 51 as well as other adjoining properties outside the Camelot Estates subdivision. See Ex. 3. Mr. Wluka proposes to divide Ms. Leonards land into two separate lots, one occupied by the existing house (Plot 73) (the House Lot) and the second an Estate Lot under § 7-4 of the Easton Zoning Bylaw (the Estate Lot). See Ex. 4. The Estate Lots driveway will cross over a portion of the pedestrian and equine easement leading to VGRs property. Id. The plan also shows a stone wall across that easement and various trees to be planted between the House Lot and the Estate Lot, one of which would be located in the easement area. If measured along the boundary between the proposed Estate Lot and Guinevere Road as that road is depicted on the approved subdivision plan, the Estate Lot has 40.77 feet of frontage. If measured along the arc of the turning easement near the end of that road, frontage is less than 40 feet. The Board accepted the 40.77 foot frontage measurement and granted Mr. Wlukas application for an Estate Lot special permit on March 12, 2008. VGR timely appealed that Decision to this court.

Additional facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

Only a person aggrieved by a zoning board decision has standing to appeal. G.L. c. 40A, § 17. Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Watros v. Greater Lynn Mental Health & Retardation Assn, Inc., 421 Mass. 106 , 107 (1995); Green v. Board of Appeals of Provincetown, 404 Mass. 571 , 574, 536 N.E.2d 584 (1989).A plaintiff qualifies as a person aggrieved upon a showing that his or her legal rights will be infringed by the boards action. To show an infringement of legal rights, the plaintiff must show that the injury flowing from the boards action is special and different from the injury the action will cause the community at large. Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005) (citations omitted). Furthermore, the injury must be to a specific interest that the applicable zoning statute, ordinance, or bylaw at issue is intended to protect. Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 30 (2006) (citing Circle Lounge & Grille, Inc. v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 324 Mass. 427 , 431 (1949)).

Under G. L. c. 40A, an abutter is presumptively a person aggrieved. G. L. c. 40A, § 11; Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. However, a defendant may challenge the plaintiffs standing by offer[ing] evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33 (quoting Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 258 (2003)). [Note 5] Once the presumption has been rebutted, the issue of standing is decided on the basis of the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiff from the presumption. Id. (quoting Barvenik v. Aldermen of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132 (1992)); Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721.

Whether a plaintiff has proved standing is a question of fact for the court. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721; Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 440. However, this does not require that the factfinder ultimately find a plaintiffs allegations meritorious. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. Standing is the gateway through which one must pass en route to an inquiry on the merits. When the factual inquiry focuses on standing, therefore, a plaintiff is not required to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that his or her claims of particularized or special injury are true. Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 440-41. The plaintiff is only required to put forth credible evidence to substantiate his allegations. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721.

The court in Butler addressed what constitutes credible evidence in zoning cases.

Although decided zoning cases have not discussed the ingredients of credible evidence, cases discussing the same concept in other contexts have observed that credible evidence has both a quantitative and a qualitative component. We think the same approach is appropriate here. Quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made. Qualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the boards action. Conjecture, personal opinion, and hypothesis are therefore insufficient. When the judge determines that the evidence is both quantitatively and qualitatively sufficient, however, the plaintiff has established standing and the inquiry stops.

Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441-42 (citations omitted).

VGR is an abutter and thus has the presumption of standing. Mr. Wluka challenges this presumption under a variety of theories. First, Mr. Wluka has submitted into the record VGRs Articles of Organization, contending that in order for VGR to have standing, it must show that his plan harms VGRs corporate legal rights. See e.g., Harvard Square Defense Fund v. Planning Bd. of Cambridge, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 491 , 495 (1989); Chongris v. Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 17 Mass. App. Ct. 999 , 1000 (1984). Mr. Wluka contends that VGR is engaged in the business of selling janitorial supplies and the development of land abutting VGRs property is entirely unrelated to those business activities. Mr. Wlukas corporate harm theory is not sufficient to overcome the presumption of standing. Although VGRs ownership of this vacant parcel may have little bearing on its day-to-day business, the corporation is the property owner. This fact distinguishes this action from Harvard Square Defense Fund and Chongris where the entities in those cases did not own property in the impacted zoning district. [O]nly a limited class of individualsthose whose property interests will be affectedis given the standing to challenge the boards exercise of its discretion. Harvard Square Defense Fund, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 492 (internal quotations and citations omitted). It is irrelevant that VGRs chief stated corporate purpose is the sale of janitorial supplies. As its Articles of Incorporation make clear, it also has the right to engage in all other business or activities that are lawful under the laws of Massachusetts. As the owner of the abutting lot, VGR has a definite property interest at stake, which is sufficient for standing purposes.

Mr. Wluka next challenges VGRs presumptive standing by contending that the claimed harminterference with the easement leading to VGRs propertyis not specific to VGR since the right to use the easement is shared by all property owners in the subdivision. Again, this challenge fails. While VGR does not have exclusive rights to the easement, its interest is sufficiently different from the other property owners in the subdivision. All other owners have frontage and access their lots by the various roads in the subdivision. VGRs only means of access is by way of this easement. Thus, the harm claimed is particular to VGR and not the rest of the subdivision community.

Mr. Wluka does succeed in rebutting VGRs presumption of standing through his submission of an affidavit from Brian Murphy, a professional land surveyor and President of Hayward-Boynton & Williams, the firm which designed both Mr. Wlukas Estate Lot plan and Mr. Antoscas Camelot Estates plan in 1970. Mr. Murphys affidavit shows that the proposed driveway across the easement will match the existing grade, and thus will not interfere with VGRs use of the easement. Further, he states that the stone wall shown on the plan was added for aesthetic purposes and will not be constructed within said easement area. See Aff. of Brian J. Murphy at 7. As his testimony establishes, such adjustments are entirely common in my professional experience [and are referred to as] a field conditions change [that] does not affect the validity of the Estate Lot approval. [Note 6] Id. at 7-8.

Having offered evidence sufficient to warrant a finding contrary to the harm alleged by VGR, the burden of proving standing remains on the plaintiff. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35. VGR must thus put forth credible evidence to substantiate its allegation of harm, and must also show that the injury complained of is to an interest the zoning scheme seeks to protect. Id. at 32. It has not done either.

First, VGR has not made any credible showing of actual harm. A grade-level driveway across an easement does not impede its use by pedestrians or horses in any way, and VGR has not credibly shown otherwise. The stone wall will not be built and the sole tree in the easement will be removed if requested.

Second, VGR has not shown that the interest it seeks to protect, specifically its easement rights, is an interest protected by the zoning bylaw. VGR contends that these rights are within the scope of the bylaw where one of the bylaws stated purposes is to facilitate the adequate provisions of transportation. Town of Easton Zoning Bylaw, Section I, p. 1-1. I disagree.

The essential purpose of any zoning law is to stabilize property uses in the specified districts in the interests of the public health and safety and the general welfare

. Kane v. Bd. of Appeals of Medford, 273 Mass. 97 , 104 (1930). Protecting the public health, safety and welfare may include addressing transportation and access issues. The Easton zoning bylaw accomplishes this purpose by, among other things, regulating curb cuts and driveways, ensuring that traffic signs and lights are not obscured, and empowering the special permit granting authority to consider traffic congestion and pedestrian safety before issuing a special permit. In this case, it did so. VGRs easement rights, however, are separate and distinct from the transportation interests that are protected under the zoning bylaw, and must be enforced by resorting to the law of easements, not by challenging the issuance of a special permit. See e.g., Titanium Group LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of the City of Brockton, 17 LCR 67 , 75 (2009) (rejecting plaintiffs theory of standing resulting from increased traffic over easement burdening its property and further reasoning that a contrary ruling could pose the danger that certain other tangentially related bodies of law could be subsumed into the body of land use regulation, and because those other bodies of law may provide parties alternative and more appropriate channels for redress.).

If Mr. Wluka should interfere with VGRs easement rights by erecting obstructions in the easement area, [Note 7] easement law, rather than zoning law, affords protection against unlawful interference with such rights. See e.g., M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 91 (2004) (owner of servient estate may make all beneficial use of his property so long as it is consistent with the right of the easement holder); Killion v. Kelley, 120 Mass. 47 , 52 (1876) (one having rights in a way may make reasonable improvements that would not render the way less convenient and useful to another who has equal rights in the way). Having concluded that VGRs easement rights are not an interest protected by the zoning bylaw and, in any event, that VGR has not shown any actual interference with those rights, its appeal of the Boards decision to issue a special permit to Mr. Wluka is hereby DISMISSED for lack of standing.

Were I to find otherwise and reach the merits of the case specifically, whether the Wluka property has the requisite 40 frontage for an Estate Lot, the subject of the cross-motions for summary judgment the result would be no different. VGRs contention that such frontage is lacking is simply incorrect and, in any event, the Boards ruling that such frontage exists falls well within the zone of deference allowed that Board in interpreting the bylaw. See Berkshire Power Development Inc. v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Agawam, 43 Mass. App. Ct. 828 , 832 (1997).

Summary judgment may properly be granted when there is no genuine dispute of material fact and judgment may be entered on the undisputed facts as a matter of law. See Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). The material fact is the amount of frontage and that, in turn, depends on the proper place of measurement. Mr. Wluka measured his frontage at the boundary line between his proposed Estate Lot and the northern edge of Guinevere Road as shown on the approved subdivision plan, a distance of 40.77 feet. See Ex. 4. VGR contends that that is not the appropriate measurement, citing the current frontage definition which provides that for lots abutting curved streets or cul-de-sacs, frontage is the arc length between the side lot lines. That current frontage definition, however, was added to the bylaw by vote of Town Meeting on May 19, 2008. Mr. Wlukas plan was approved by the Board on March 12, 2008, when the Towns bylaw defined frontage simply as [t]he horizontal distance measured along the front lot line between the points of intersection of the side lot lines with the front lot line. The 40.77 measurement fully complies with that definition. [Note 8]

VGR contests this by arguing that Guinevere Road ends at the western edge of the cul-de-sac and does not continue westerly to the abutting property line. The distance between the edge of the cul-de-sac and the abutting property is approximately 20 feet, which Mr. Wluka relies on to meet the 40 foot requirement. See Ex. 4. In support of its argument, VGR submitted an affidavit from Mr. Antosca (the developer of the subdivision in his capacity as president of Antosca Construction), stating that Guinevere Road was designed to terminate at the cul-de-sac and was never intended to continue to the abutting property to the west. This affidavit, however, plainly contradicts the definitive subdivision plan, which shows the parallel lines of Guinevere Road continuing beyond the turning easements to the abutting property. See Exs. 1 & 2. It is thus of no effect. See Ng Bros. Constr. Inc. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 647-48 (2002) (partys characterization of documents cannot contradict the documents themselves); OBrien v, Analog Devices, Inc., 34 Mass. App. Ct. 905 , 906 (1993). The affidavit of Brian Murphy, the current president of Hayward-Boynton & Williams (the creator of the subdivision plan) explains why the intervening 20 feet between the edge of the cul-de-sac and the abutting property was always intended to be part of Guinevere Road. As he states in that affidavit:

The recorded plan for Guinevere Road shows a stub extending beyond the turning easement. The purpose of this stub. . .was to allow for the potential future development of [the abutting property to the west]....It is not uncommon for the reviewing authorities to require that newly created road layouts extend to abutting property lines within areas where the adjacent property had potential for future development. This would allow for future integration of utilities within the development and could eliminate long dead-end streets which are often viewed as potential hazards by safety officials.

Aff. of Brian J. Murphy at 6. [Note 9] VGR asserts ownership of this 20 foot space, claiming that Mr. Antosca reserved that land when he conveyed the subdivision property in the 1970s and subsequently conveyed this interest to VGR in 1997. But there is simply no support in the record for this contention. None of the deeds provided describe such a reservation. VGR has never paid taxes on that land, and an unchallenged title examination by Attorney Felix Cerrato concludes that VGR has no fee interest in any part of Guinevere Road, including this 20 foot section beyond the edge of the cul-de-sac.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, VGRs complaint is DISMISSED IN ITS ENTIRETY, WITH PREJUDICE, and the Boards decision granting the Estate Lot special permit to Mr. Wluka is AFFIRMED. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

V.G.R. NORTHEAST INC. v. CHRISTINE SANTORO, COLIN GILLIS, CAROL SYMMONS, WALTER JOHNSON and GEORGE STRANGE as members of the PLANNING AND ZONING BOARD for the town of EASTON, and AARON WLUKA.

V.G.R. NORTHEAST INC. v. CHRISTINE SANTORO, COLIN GILLIS, CAROL SYMMONS, WALTER JOHNSON and GEORGE STRANGE as members of the PLANNING AND ZONING BOARD for the town of EASTON, and AARON WLUKA.