ROBERT J. FAIR vs. MANHATTAN INSURANCE COMPANY. SAME vs. GREENWICH INSURANCE COMPANY. SAME vs. MARKET INSURANCE COMPANY.

ROBERT J. FAIR vs. MANHATTAN INSURANCE COMPANY. SAME vs. GREENWICH INSURANCE COMPANY. SAME vs. MARKET INSURANCE COMPANY.

A policy of insurance against fire upon goods in a certain building named, without further representation or limit as to their situation, covers them in whatever part of the building they may be at the time of the loss, although at the time of the issuing of the policy they were all in one store in the building, and though a plan referred to in the policy shows the building divided into several stores, the reference to the plan appearing to be made solely to show the relative situation of the building to other buildings.

An objection to the report of an auditor to whom had been referred an action on a policy of insurance against fire, that he had exceeded his powers, in stating the amount claimed by the plaintiff and the manner in which it was calculated, in stating the amount of the plaintiff's loss by theft as well as by fire, in giving the testimony of witnesses and the considerations which affected its weight in his mind, in stating that the sum the plaintiff should recover was an estimate not entirely satisfactory to him and probably covering the amount of the goods actually consumed by fire, should be taken by a motion to recommit the report; and when taken for the first time when the report is offered in evidence, a ruling of the court allowing the whole report to be read by the jury is not the subject of exception, when it appears that the court at the same time gave proper instructions as to the use and effect of the report as evidence.

ACTIONS OF CONTRACT to recover for alleged losses by fire under three policies of insurance, one issued by each of the defendant companies. The actions were tried together. The Manhattan Insurance Company insured the plaintiff against loss or damage by fire "on stock of dry goods and other merchandise, hazardous and extra hazardous, his own or held by him in trust or on commission, or sold but not delivered, contained in the frame building known as Hunt Building, situate on Main Street in the village of Northampton, Mass., as per plan filed in this office, and on his store furniture and fixtures also contained in

Page 321

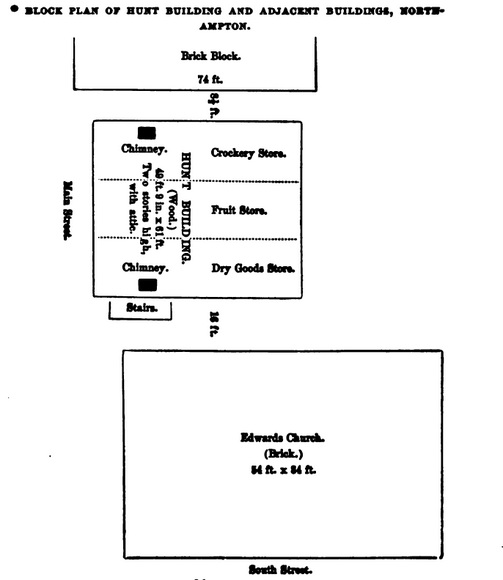

said building." The policies issued by the other companies were the same, except that they did not contain the risk upon the furniture and fixtures; and, while the policy of the Greenwich Insurance Company referred to a plan filed in the office of Rathbone, Greig & Hamblin in the city of New York, the policy of the Market Insurance Company contained no reference to a plan. The plans referred to were like the one given in the margin.

BLOCK PLAN OF HUNT BUILDING AND ADJACENT BUILDINGS, NORTHAMPTON.

Page 322

These cases, with one against the Commonwealth Insurance Company, which was subsequently settled, were by the Superior Court referred to an auditor under the following rule: "And now it is ordered by the court that Samuel T. Spaulding, Esq., be, and he hereby is appointed auditor in the above mentioned actions, to hear the parties and examine their vouchers and evidence, and to state the accounts and make report thereof to the court; and if either party neglects to appear on due notice, then the auditor is to proceed ex parte."

The auditor made the following report:

"The plaintiff was insured on his stock of dry goods in the frame building known as the Hunt Building, situate on Main Street in Northampton, from the 19th of March 1870 to the 19th of March 1871, to the amount of $2000, by policy issued by the Commonwealth Fire Insurance Company of the city of New York, in which a plan of the premises is referred to as filed in the office of Rathbone, Greig & Hamblin; to the amount of $1500, by policy issued by the Greenwich Insurance Company of the city of New York, in which the same plan is referred to, from the 19th of March 1870 to the 19th of March 1871; to the amount of $3500, by policy issued by the Manhattan Insurance Company in the city of New York, as per plan filed in the office of the company, being the same as, or similar to, the plan above named, from the 9th of December 1869 to the 9th of December 1870; and to the amount of $2500, by policy issued by Market Fire Insurance Company in the city of New York, in which no plan is referred to, and the building is described not as the Hunt Building, but as the framed building owned by B. North, from the 17th of October 1869 to the 17th of October 1870. No question was made that the same premises were not referred to in the last named policy as in the others. The plaintiff was insured also by the policy from the Manhattan Insurance Company to the amont of $600, on his store furniture and fixtures also contained in said building.

"The plan referred to represents the story of the Hunt Building opening immediately from the street, as divided into three rooms, parallel to each other and extending from front to rear

Page 323

the middle room being the smallest, and the east and west rooms about equal to each other in size. The plaintiff occupied the west room at the time the policies were issued, and there carried on business, where the goods, furniture and fixtures insured were then situated. The other rooms were occupied and used as stores severally by other parties. At the hearing the plaintiff testified that the shape of the room thus occupied by him was different from that represented on the plan, in this, that the middle room extended only about half way from the front to the rear of the building, and the space in the rear of that room was then included in the west room, and was part of the store occupied by him with his goods, furniture and fixtures.

"The building was wholly consumed by fire on the 19th of May, 1870. Due notice was given, and proof made by the plaintiff of his loss, to the defendants. Between the time the insurance was effected and the time of the fire, the plaintiff entered into possession of the east and middle rooms, took away the partition separating the west and middle rooms, and filled the whole space afterwards constituting only two rooms, designated as the East and West rooms, with goods, fixtures and furniture, and carried on trade therein until and at the time of the fire.

"The plaintiff claimed $8,905.19 as his loss on the goods, including the value of the goods burnt, and the damage to goods by their removal, besides $156.50 damage to the furniture and fixtures, and these actions were brought to recover those sums. It was agreed that the sum of $596.78 should be taken as a correct estimate of the damage to the goods saved, and $156.50 of the damage to the furniture and fixtures, as settled by appraisers mutually chosen. The plaintiff testified that he calculated the loss on the goods by adding together the cost of goods on hand the 14th of February 1870, as per inventory then taken, and the cost of goods purchased between that day and the 19th of May, as shown by invoices, and subtracting from the amount the cost of goods sold during the same period, and the value of the goods saved as ascertained by the said appraisers. To determine the cost of goods sold, he deducted from the price of cash sales, in the ordinary business of the store, 33 per cent., and from the

Page 324

price of goods supplied to a store at Amherst, and another store at Easthampton, 12 1/2 per cent.

"Allowing for errors in invoices, or in the statement of them in evidence, and in the calculation of the cost of goods sold, I find that the whole loss on the goods, including the value of the goods burnt and stolen, and damage to goods saved by their removal, was at least $7000. Deducting the appraised damage to the goods saved, I find that $6403.22 was the value of the goods burnt and stolen.

"The defendants claimed as a matter of law to be referred to the court, that by the terms of the policies they were not liable for goods burnt in, or damaged by removal from any part of the store except what was the west store at the time the insurance was effected, nor for goods stolen. The questions therefore presented at the hearing for my decision, depending upon the said question of law, were, 1st. What was the value of the goods burnt in that part of the building occupied by the plaintiff at the time of the fire. 2d. What was the value of the goods burnt in that part which was originally the west store, and the damage to goods and furniture and fixtures removed from that part? and 3d. What are the proportions, and shares of the loss, in each case to be sustained by the defendants respectively?

"Several witnesses testified in behalf of the defendants that they assisted in removing goods from the store at the time of the fire, that the fire broke out under the roof, in the rear, about midway between the ends of the building; that the store was lighted with gas; that all the goods were removed, except articles of small value, varying in the opinions of the witnesses from $50 to $150; that drawers, a counter, and case doors, and a desk were carried out; that they went over all parts of the store, and some saw no goods, except trifling articles scattered about the floor, and others only those and a few articles hanging upon a string; that they were finally driven out by the fire from the west store, the plaintiff coming out last with his arms full of goods, and especially that the west store was cleared of goods; also that the plaintiff afterwards said that there were not many goods left in the store, but a great many were stolen. On the other hand was

Page 325

the presumption that the missing goods remained in the store until it was shown they were carried out, and that the observation of witnesses in the confusion, hurry and alarm of the fire, especially as to parts of the stores to which they did not seem to have given particular attention, was likely to be superficial and inaccurate. On the whole evidence therefore, I find that the larger part of the goods missing was removed; that the west store was nearly cleared; and that the goods, visible to the witnesses who testified, were few and comparatively of little value; and I have no certain guide as to the value of the goods which might remain unnoticed. However, I make the following estimate, not entirely satisfactory to myself, as probably covering the amount of goods actually consumed by fire.

Value of goods burnt in what was the west store . $ 200

Value of goods burnt in what became the east store of the plaintiff . 1000

which sums, with $596.78, the damage to goods removed, make $1796.78, to be apportioned among the defendants if they are liable for the whole loss, besides $156.50, the damage to the furniture and fixtures, to be charged to the Manhattan Insurance Company alone.

"If the defendants are liable only for the value of goods burnt in what was the west store, and the damage to goods, furniture and fixtures removed from that part of the building, then there is to be apportioned between them the sum of $498.39, being the amount of the goods burnt in that store and one half of the appraised damage to the goods, besides $78.25, being one half of appraised damage to the furniture and fixtures, to be charged to the Manhattan Insurance Company alone.

"I estimate the proportions and shares of the whole loss, if to be sustained by the defendants, as follows:

The Commonwealth Fire Insurance Co. $ 378.26 20-95

The Greenwich Insurance Co. 283.70 15-95

The Manhattan Insurance Co. $ 661.97 35-95 plus 156.50

Market Fire Insurance Co. $ 472.83 25-95

"And the proportions and shares of the partial loss, if that only is to be sustained by the defendants, as follows:

Page 326

The Commonwealth Insurance Co. $ 104.92 20-95

The Greenwich Insurance Co. 78.69 15-95

The Manhattan Insurance Co. $ 183.61 35-95 plus 78.25= $ 261.86 35-95

Market Fire Insurance Co. 131.15 25-95

"In the foregoing estimates and apportionments of damages, no part of the value of goods stolen has been included."

Trial in the Superior Court, before Rockwell, J., who, after a verdict for the plaintiff, allowed the defendants' following bill of exceptions:

"The plaintiff offered the auditor's report in evidence; the defendants objected to the reading of any part of it to the jury except the findings of the auditor on the matter into which he was ordered by the rule to inquire; but the court overruled the objection, and permitted the whole report to be read in evidence. The court gave proper instructions as to the use and effect as evidence of the auditor's report.

"The plaintiff testified that when the policies were written, the main floor of the building was divided into three stores, the easternmost of which was occupied by one Arnold as a crockery store and extended from front to rear of the building; the middle one was occupied as a confectionery and fruit store, and extended through only a part of the depth of the building; the west store extended through the entire depth of the building and in the rear of the middle store. The plaintiff, when the insurance was effected, occupied only this west store. At the time of the fire he occupied the whole floor of the building, having removed the partition between the west and middle store, and opened passage ways and doors into the east store. The stock was in all parts of the main floor of the building.

"The defendants in each case asked the court to rule that the plaintiff could not recover for loss of or injury to any part of the stock; and the Manhattan Company, that he could not recover for loss of or injury to furniture or fixtures which were contained in that part of the building which he did not occupy when the insurance was effected; but the court declined so to rule, and did rule that the plaintiff was entitled to recover for all loss of or injury to goods, furniture or fixtures in any part of the building."

Page 327

The case was argued September term 1872, by

A. L. Soule & E. H. Lathrop, for the defendants.

G. M. Stearns & C. E. Smith, for the plaintiff.

MORTON, J. The policies of the Manhattan Insurance Company and of the Greenwich Insurance Company each describe the property insured as a "stock of dry goods and other merchandise hazardous and extra hazardous, his own or held by him in trust or on commission, or sold but not delivered, contained in the frame building known as Hunt Building, situate on Main Street in Northampton, as per plan." The policy of the Market Insurance Company contains substantially the same description except that there is no reference to a plan. At the time the policies were issued, the main floor of the building was divided into three stories, as shown on the plan, and the plaintiff occupied the west store, the others being occupied by other persons. The building was wholly consumed by fire on May 19, 1870. At the time of the fire, the plaintiff occupied the whole of the main floor, having removed the partition between the west and middle store, and opened doors into the east store. The defendants contend that the policies covered the goods contained in the west store only. It was not shown or claimed that the removal of the goods by the plaintiff increased the risk, and we are of opinion that this case is not distinguishable in principle from the case of West v. Old Colony Insurance Co. 9 Allen 316. The words of the policies in suit include all the three stores, and there is nothing in them to indicate that the plaintiff occupied or intended to occupy only one of them, or that the intention of the parties was to limit the risk to goods contained in the store then in fact occupied by him. The reference to the plan was for the purpose of showing the situation of the building in relation to other buildings. The ruling that the plaintiff was entitled to recover for all loss of or injury to goods, in any part of the building, was correct.

Before passing upon the exception to the ruling admitting the auditor's report, the court desire a further argument upon the questions, 1st. Whether the auditor exceeded his authority in the manner in which he has stated the case; and 2d. Whether

Page 328

the objections to the report could be first taken at the trial, or should have been taken by a previous motion to recommit.

Further argument ordered.

The case was accordingly reargued upon these questions at September term 1873.

A. L. Soule, for the defendants.

M. P. Knowlton, (G. M. Stearns with him,) for the plaintiff.

GRAY, C.J. The bill of exceptions presents important questions of practice, which have been fully and ably argued, as to the powers of auditors appointed in actions at law, and the method of dealing with their reports when returned into court.

The Rev. Sts. c. 96, §§ 25, 30, (substantially reenacting the St. of 1817, c. 142,) provided that when in any action it should appear that an investigation of accounts and examination of vouchers was required, the court might appoint one or more auditors to hear the parties, examine their vouchers and evidence, state the accounts between them, and make report thereof to the court; and that such report, if there should be no legal objection to it, might be used as evidence to the jury, subject to be impeached by evidence produced by either party on the trial. An auditor so appointed was authorized to hear and determine all matters of fact involved in the issue so referred to him. Locke v. Bennett, 7 Cush. 445.

But in Whitwell v. Willard, 1 Met. 216, it was held by a majority of the court that an action of tort, the trial of which would not require an investigation of accounts or an examination of vouchers, although it would require the introduction of a great mass of evidence in detail before the jury, could not be referred to an auditor. The St. of 1856, c. 202, provided that in any action, whether of contract, tort or replevin, the court might appoint auditors to hear the parties and report upon such matters as might be directed by the court, and their report should be prima facie evidence upon those matters only. The purpose of this statute was to enlarge the class of cases which might be referred to auditors, not to affect in any way the extent of their authority with regard to the matters submitted to

Page 329

them. Quimby v. Cook, 10 Allen 32. Section 46 of c. 121 of the Gen. Sts. is a condensed reenactment of the earlier statutes.

An auditor's report is not governed by all the rules regulating the admission of ordinary evidence offered by either party. It is the report of an officer appointed by the court under authority of the statute. It is made by the statute prima facie evidence, and prima facie evidence only, upon such matters as are referred to the auditor. It does not, technically speaking, change the burden of proof. Morgan v. Morse, 13 Gray 150. The object of the statute is to simplify and elucidate the trial of those matters, and is not to be defeated or evaded at the election of either or both parties. If the plaintiff relies on the auditor's report at all, he may be required to read the whole of it; but the part which is unfavorable, as well as that which is favorable to him, is only prima facie evidence. Fogg v. Farr, 16 Gray 396. As the court may refer a case to an auditor without, or even against, the consent of the parties, it may require his report to be read at the trial, although neither party desires it. Clark v. Fletcher, 1 Allen 53.

An auditor is not limited in his report to a naked summary of the facts found or of the account between the parties, but may at his discretion include in it a narrative of the circumstances of the case, and a statement of the evidence given before him and of his reasons for his conclusions; such a statement may be considered by the jury; and the respect which they should pay to his report may be affected by the manner in which he appears to have performed his duty. When the statute makes the report prima facie evidence, it does not establish an invariable measure of the degree of confidence with which the jury shall receive the auditor's report. It merely gives the party, in whose favor the auditor reports, the benefit of his finding in the first instance, and declares it to be sufficient to support the claim or defence, unless in the opinion of the jury it is overcome by other evidence. But, in determining whether it has been so overcome, the jury may take into consideration the manner in which the auditor appears by the report itself to have performed his duty, as well as any other competent evidence introduced at the trial upon the matters referred to the auditor and reported upon by him.

Page 330

In Commonwealth v. Cambridge, 4 Met. 35, which was a suit against a town to recover back money overpaid for the support of state paupers, Mr. Justice Wilde said: "Nor can we admit that the auditor has exceeded his authority, as the attorney general contends, by estimating the value of the paupers' labor. The auditor was directed to state the accounts, and report the same to the court. To do this, it was necessary to ascertain the value of the paupers' labor. The auditor's judgment is not conclusive; it may be impeached by the evidence reported, and by other evidence, and it may be controlled by the jury. But his judgment is entitled to great respect, for he appears to have examined the subject most thoroughly. The witnesses best acquainted with the ability of the paupers to labor and the labor they actually performed were examined, and every other source of information was resorted to, which could be expected to aid him in forming a correct judgment. The evidence, and the reasons of his opinion, are reported; so that the jury had ample means to correct the auditor's judgment."

In Jones v. Stevens, 5 Met. 373, it was said by Mr. Justice Hubbard, and decided by the court, that "where the evidence offered bears directly or incidentally on the matters of account, there the auditor is called upon to examine it, and may state it, if he thinks it necessary to render his report intelligible; though he is not required, as a matter of course, to detail the testimony at length."

In Taunton Iron Co. v. Richmond, 8 Met. 434, Chief Justice Shaw said: "The report of an auditor is prima facie evidence for the party in whose favor it is made, in regard to any item; subject to the reconsideration of the jury, either upon the evidence contained in the report, or upon any other counteracting evidence; and this rule is not changed by the fact that the auditor, at the request of either party, or otherwise, has reported the evidence from which he drew his conclusions."

The very object of appointing auditors, as stated by Chief Justice Bigelow in Clark v. Fletcher, 1 Allen 53, is "that a preliminary investigation should be had under the authority of the court, by means of which the precise points in controversy can be ascertained,

Page 331

and the evidence bearing on them stated in a clear and condensed form, so that a jury may be able intelligibly to pass upon the issues with facility and without unnecessary loss of time."

The auditor's report is the only form in which he can be permitted to state what took place before him, and he cannot be called as a witness for the purpose of adding to or controlling it. But a party dissatisfied with the report may, in order to affect its weight, prove by a witness, whom he calls at the trial, that he did not testify before the auditor. Kendall v. Weaver, 1 Allen 277. Monk v. Beal, 2 Allen 585. Packard v. Reynolds, 100 Mass. 153.

In Lincoln v. Taunton Copper Co. 9 Allen 181, in which the order of reference was to three auditors, and it was held that the report of one who dissented from the others could not be read to the jury, but that only the report of the majority was admissible as prima facie evidence, Mr. Justice Dewey said: "The fact will always appear from the report itself that it had not the concurrence of all the auditors."

The finding of an auditor upon a matter not embraced in the reference to him should be stricken out by the court at the trial, or the jury instructed to disregard it. Jones v. Stevens, 5 Met. 373. Snowling v. Plummer Granite Co. 108 Mass. 100. If the auditor reports the facts on which his conclusions are founded, and these facts are not sufficient in law to support the conclusions, the court should instruct the jury accordingly; and such instructions, being upon a pure question of law, may be revised by bill of exceptions. Ropes v. Lane, 9 Allen 502. Morrill v. Keyes, 14 Allen 222.

But the court may for any sufficient cause recommit the report to the same or another auditor for revision. Rev. Sts. c. 96, § 29. Gen. Sts. c. 121, § 49. An objection to the form of the report, to the fulness or manner in which the auditor has stated the evidence or the reasons by which he has been influenced, or to the qualifications of witnesses testifying before him, should be raised by motion to recommit the report for amendment before the trial. Allen v. Hawks, 11 Pick. 359. Jones v. Stevens,

Page 332

5 Met. 373. Leathe v. Bullard, 8 Gray 545. Kendall v. May, 10 Allen 59. And the ruling upon such a motion, at least when first made during the trial, is not a subject of exception. Kendall v. Weaver, 1 Allen 277. Packard v. Reynolds, 100 Mass. 153.

In Allen v. Hawks, 11 Pick. 359, Chief Justice Shaw said: "It is no doubt competent for the court in the first instance to decide upon the acceptance of the report, upon exceptions or otherwise. It is for the court to determine whether the auditors have pursued their authority and completed their duty, and conducted honestly and correctly, and to accept, reject or recommit the report."

In Jones v. Stevens, 5 Met. 373, which was an action for work and labor performed for the defendant, one ground of defence was that the work was done by the plaintiff and another person as partners; both parties introduced evidence before the auditor upon the question of partnership, and his report stated his conclusion upon that question and the facts on which it was based; objection was taken on this ground to the admission of the report in evidence at the trial, and overruled by the presiding judge; his instructions, as understood by this court, were "that the facts, as stated in that part of the report, so far made a part of it, that they might be read to the jury; but that the opinion formed by the auditor upon those facts, in relation to the partnership, should be excluded from their consideration;" and this court held that, although the auditor was not required to determine the question of partnership, yet the course adopted by the judge, "in rejecting the conclusions drawn by the auditor, while he retained the facts upon which the conclusions were formed, was within the exercise of his discretion, and that his decision in this respect was not erroneous."

In Leathe v. Bullard, 8 Gray 545, it was held that, at the argument in this court on a bill of exceptions, the competency of evidence introduced before the auditor could not be objected to by a party who had neither moved to have the report recommitted to the auditor, nor to have the objectionable parts stricken out, in the court below; and the court had no occasion to consider whether a

Page 333

motion to strike out at the trial would have been a matter of right when no motion to recommit had been made.

In Kendall v. May, 10 Allen 59, it was held that evidence of the insanity of a witness, who had been allowed by the auditor to testify before him, could only be introduced upon a motion to recommit the report, and that the judge was not obliged to entertain such a motion after the trial had begun; and the inconvenience of correcting the auditor's report, on account of any error of fact or of law, pending the trial before the jury, was forcibly pointed out.

The objections, made at the argument upon this bill of exceptions, to the report of the auditor, to whom had been referred several actions upon policies of insurance issued by the defendants to the plaintiff on the same risk, were that the auditor stated the amount claimed by the plaintiff and the manner in which it was calculated, the whole amount of the loss as found by the auditor, the testimony of several witnesses, and the considerations which affected its weight in the auditor's mind; and that the sum which he found the plaintiff to be entitled to recover was an "estimate, not entirely satisfactory to" the auditor, and "probably covering the amount of the goods actually consumed by fire." As to these statements, and particularly the last one, it was argued, on the one side, that the tendency would be to produce an impression upon the jury that the loss sustained by the plaintiff was at least equal to the sum reported by the auditor, and might have been more; and on the other, that if the auditor was not fully satisfied of the correctness of his conclusions, it was his duty, or at least within his discretion, so to state in his report, in order that the jury might be informed more exactly of the result of his deliberations upon the case, and be better enabled to judge of the weight to which, when compared with the other evidence introduced before them, his conclusion was really entitled.

We are of opinion that these considerations were proper to be submitted to the court below, in the first instance, upon a motion, before the trial, to recommit the report to the auditor; and that when, as in the present case, no such motion was made, but the report was objected to for the first time when offered in evidence,

Page 334

and when the bill of exceptions states that the court gave proper instructions to the jury as to the use and effect as evidence of the auditor's report, the ruling of the presiding judge, refusing to strike out any part of the report, and allowing the whole to be read to the jury, does not entitle the defendants to a new trial.

Exceptions overruled.