EDWARD JACKSON & others vs. JAMES STEVENSON

EDWARD JACKSON & others vs. JAMES STEVENSON

Restriction in Deed - Acquiescence - Changed Conditions - Refusal to enjoin - Damages.

A tract of land was divided into lots which were sold subject to restrictions in the deed, which restrictions were designed to make the locality a suitable one for residences. Owing to the general growth of the city and the use of the neighborhood for business, the purpose of the restrictions could no longer be accomplished. Held, on a bill in equity brought by the owner of one of the lots praying that the owner of two of them be enjoined from violating the restrictions relating to the erection of out-buildings, that it would be oppressive and inequitable to give effect to the restrictions; and, since the changed condition of the locality had resulted from other causes than their breach, to enforce them in this instance could have no other effect than to harass and injure the defendant, without effecting the purpose for which the restrictions were originally made.

A bill in equity was brought to enforce the restrictions in a deed, but, on account of changed circumstances, the court refused to grant an injunction. It appeared by the master's report that the plaintiffs were entitled to some damages. Held, that, as the plaintiffs had no remedy at law against the defendants, the bill should be retained for the purpose of assessing the plaintiffs' damages.

Page 497

BILL IN EQUITY , filed on July 13, 1891, praying that the defendant be restrained from erecting any building in violation of the provisions of a deed. Hearing on the bill, answer, master's report, and plaintiffs' exceptions, before Knowlton, J., who reserved the case for the consideration of the full court. The facts appear in the opinion.

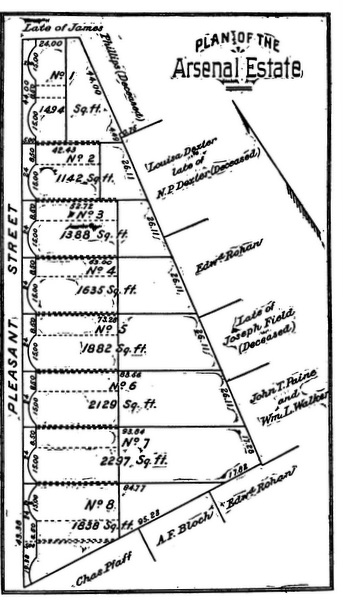

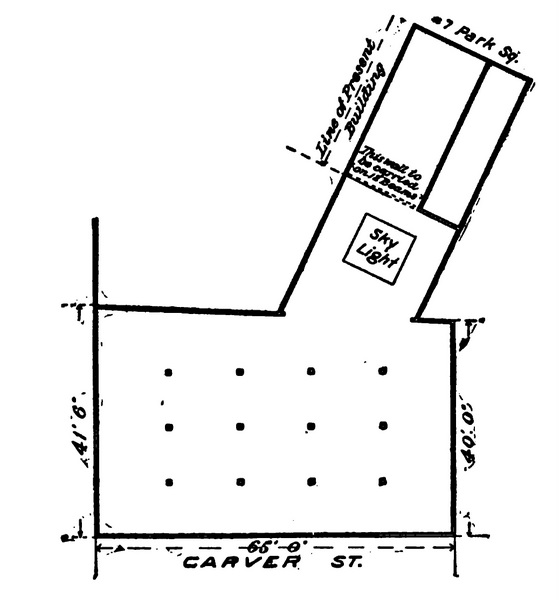

The premises are shown on the accompanying plans.

C. Almy, (H. M. Spelman with him,) for the plaintiffs.

W. A. Hayes, Jr., for the defendant.

BARKER, J. In the year 1853 the city of Boston owned a parcel of land known as the Arsenal Estate, in the vicinity of the southerly end of the Common. The lot was triangular, but truncated at the northerly end towards the Common, and contained an area of about 14,000 square feet, bounded on the west by Pleasant Street, now known as Park Square, and on the other side by lands of private owners. The westerly line was about 232 feet in length, and the greatest depth perpendicular to this line was about 100 feet, while at the northerly end the depth was about 24 feet. At this time the estates surrounding the Common were chiefly used for the more expensive residences. The city caused the land to be divided into eight lots and sold. The most northerly and southerly lots, numbered respectively 1 and 8, were each about 44 feet wide, and each of the other lots was 24 feet. The plaintiffs are the owners of lot No. 8, while the defendant is the owner of lots numbered 4 and 5; the other lots are owned by different persons, all deriving title through separate deeds from the city. Each lot was divided, by lines parallel with Pleasant Street, into front and rear portions. The front portion of lot No. 1 was 18 feet deep; of lot No. 2, 32 feet; and of the other lots, 40 feet. In order to provide a general building scheme, and to effect a uniform plan, certain restrictive clauses, intended for the benefit of the lots and of the neighborhood, were inserted by the city in its deeds. The first of these clauses related to partition walls, the second to the front lines of the buildings, and the third required the buildings to be of a width equal to the width of the front of the lot. The fourth restrictive clause provided that "No dwelling-house or other building except the necessary outbuildings shall be erected or placed on the rear of the said lot." The fifth clause was as follows: "No

Page 498

Page 499

building which may be erected on the said lot shall be less than three stories high, exclusive of the basement and attic, nor have exterior walls of any other material than brick, stone, or iron, nor be used or occupied for any other purpose or in any other way than as a dwelling-house, apothecary's shop, dry goods store, or grocery store, during the term of twenty years from August 25, 1853."

The city conveyed the lots Nos. 4 and 5 in 1856, and the plaintiff's lot, No. 8, in 1858. All the lots were conveyed by the city before the year 1864, and dwelling-houses of substantially uniform design were built, which now remain upon lots Nos. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. The main part of each house is forty feet deep, four stories high, exclusive of basement and attic, and covers the width of its lot, extending back to the line separating the front and rear portions. On the northerly side of the rear of lot No. 7 is a two-story L, about 11 feet wide and 15 feet deep, and between 17 and 18 feet in height, the lower story of brick, and the upper of metal, with flat roof; in the rear of this L, and covering the whole width of the lot, is also a building seven feet high, of brick, connecting with a storehouse on Carver Street, which is the next street easterly. The rear building last mentioned was erected in 1886; the upper story of the L was added in 1878, and the original L existed before 1877. Since 1886 the structures on the rear of lot No. 7 have been used in a wholesale and retail apothecary business, carried on in the buildings on this lot and in connecting buildings on Carver Street. On the northerly side of lot No. 6 is an extension 32 feet high, 13 feet wide, and 14 1/2 feet deep, with a nearly flat roof, used as part of the main building. This extension has been in its present shape since 1878, and for some years before that date it was one story lower. On the rear of lot No. 3 is a brick L, 9 1/2 feet wide and 39 feet high, extending to the end of the lot. This has existed for many years, and has always been used as a part of the main building. Upon the northerly side of the rear of each of the defendant's lots have existed for many years structures about eleven feet wide, extending from the main buildings to the easterly side of the lots, with roofs sloping to the south, the north walls being about ten feet high. These extensions have been used for kitchens, laundries, and waterclosets.

Page 500

On the top of the north wall of the L on lot No. 5 there has been for many years a trellis of upright posts and crossbars, partly covered with live grape-vine.

No objection had been made by the owners of the plaintiff's estate to any structure erected on any of the lots until this case arose in 1891. The master finds that since August 25, 1873, there has been a considerable change in the character of the neighborhood, the houses being no longer used as dwellings exclusively, but devoted to a considerable extent to business purposes, and that the neighborhood is now, to all intents and purposes, a business or mercantile one. The defendant, owning property on Carver Street abutting on the rear of lot No. 4, and intending to erect a market on Carver Street, proposed to build over the entire rear portion of lot No. 4, a brick structure with a flat roof and raised skylight, for use as a part of and a connection between the ground floor of the building on lot No. 4 and his Carver Street property, designed as a store or market, its exact use depending upon future tenants. The plaintiffs, upon ascertaining this, gave notice that they should insist on a compliance

Page 501

with the restrictions, and, this notice being disregarded, brought their bill, alleging that the defendant is about to erect on lot No. 4 a building which is not a necessary outbuilding, and asking that he may be perpetually enjoined from placing on the rear of lot No. 4 or No. 5 any buildings except necessary outbuildings.

The master finds that the proposed structure is a reasonably necessary outbuilding, if, in construing the fourth restriction, the facts that the operation of the fifth restriction has ceased, and that the neighborhood is now used for general business purposes, are to be considered, unless the defendant's intention to use it in part as a connection between the Park Square and Carver Street buildings shows that it can be in no sense an outbuilding. The plaintiffs except to this part of the master's report, and also to his findings as to structures upon the rear of other lots.

The master finds that the proposed structure would cause no appreciable diminution of light or air, nor any perceptible damage to the plaintiffs' estate, beyond the possible technical damage which the law may assume; and that the structures on the rear portions of lot No. 6 and lot No. 7, which lie between the premises of the parties, are of more considerable importance as affecting the plaintiffs' premises than the proposed structure would be.

Whether the right to equitable relief is affected by acquiescence depends upon the circumstances of each case. Where such a defence is claimed, the facts relating to it become material, and may be inquired into. The exception to the finding of the master relative to structures upon the other lots must therefore be overruled. Roper v. Williams, Turn. & Russ. 18. Peek v. Matthews, L. R. 3 Eq. 515. Ware v. Smith, ante, 186.

We assume that when restrictions inserted in the deed of a particular lot are part of a general scheme for the benefit and improvement of all the lands included in a larger tract, a grantee of any part of the land may, under proper circumstances, enforce them against his neighbor; Whitney v. Union Railway, 11 Gray 359; Parker v. Nightingale, 6 Allen 341; Linzee v. Mixer, 101 Mass. 512; Tobey v. Moore, 130 Mass. 448; Beals v. Case, 138 Mass. 138; Payson v. Burnham, 141 Mass. 547; and that the restrictions inserted by the city in its deeds were of this nature. Hano v. Bigelow, 155 Mass. 341. We also assume that

Page 502

the restrictions, except as expressly limited in duration, were intended to be permanent; and that the structures which the defendant proposed to erect were not necessary outbuildings, within the meaning of the fourth restriction. Keening v. Ayling, 126 Mass. 404. Sanborn v. Rice, 129 Mass. 387, 397. Ayling v. Kramer, 133 Mass. 12, 14. Hamlen v. Werner, 144 Mass. 396. We also assume that an owner having the right to enforce such a restriction, if otherwise entitled to sue in equity, is not obliged to wait until after the objectionable structure is erected before bringing his bill; Peek v. Matthews, L. R. 3 Eq. 515; and that relief may be granted, although no actual serious pecuniary damage may have been sustained, or is to be expected; Attorney General v. Algonquin Club, 153 Mass. 447, 455; and that an owner may neglect to object to infractions of restrictions to some extent, without losing his right to enforce the restrictions when they more clearly and seriously affect him. Linzee v. Mixer, 101 Mass. 512, 531. Payson v. Burnham, 141 Mass. 547, 556.

Assuming these points in favor of the plaintiffs, we are nevertheless of the opinion that an injunction should not be granted in the present case. It is evident that the purpose of the restrictions as a whole was to make the locality a suitable one for residences; and that, owing to the general growth of the city, and the present use of the whole neighborhood for business, this purpose can no longer be accomplished. If all the restrictions imposed in the deeds should be rigidly enforced, it would not restore to the locality its residential character, but would merely lessen the value of every lot for business purposes. It would be oppressive and inequitable to give effect to the restrictions; and, since the changed condition of the locality has resulted from other causes than their breach, to enforce them in this instance could have no other effect than to harass and injure the defendant, without effecting the purpose for which the restrictions were originally made. Duke of Bedford v. British Museum, 2 Myl. & K. 552. German v. Chapman, 7 Ch. D. 271, 279. Sayers v. Collyer, 24 Ch. D. 180, 187. Columbia College v. Thacher, 87 N. Y. 311. Starkie v. Richmond, 155 Mass. 188.

But as the plaintiffs have no remedy at law against the defendant, the bill should be retained for the purpose of assessing

Page 503

their damages. Upon the master's report, they are entitled to some damages, and we do not understand him to find that, upon the view which we have taken, the damages are merely nominal. The case is to be referred to an assessor to report the damages caused to the plaintiffs by the erection of the structures which the defendant has caused to be built since the bringing of the bill, but an injunction is denied.

So ordered.