GEORGE E. ALLEN vs. CITY OF BOSTON.

GEORGE E. ALLEN vs. CITY OF BOSTON.

Public Easement - Rights of the Owner of Land under the Highway - Excavation under Sidewalk - Negligent Management of Sewers - Action - Damages.

The general easement in the public acquired by the location of a highway extends to the limits of a highway as located, and includes various underground uses, of which the construction of sewers is one.

The owner of land over which a highway is laid retains his right in the soil for all purposes which are consistent with the full enjoyment of the easement acquired by the public, subject, however, to municipal or police regulations.

The owner of land over which a highway is laid has a right to excavate under the sidewalk, if he thereby violates no ordinances or regulations of the city, or interferes with no existing public use of the street.

The owner of land over which a highway was laid extended his cellar under the sidewalk so that its outer wall came just within the outside line of the sidewalk, and to within one or two feet of a sewer in the highway which, on that side, was constructed of common field stones, and deepened the cellar so that its floor was two feet below the level of the bottom of the sewer. The owner of the land brought an action against the city for damages for injuries occasioned by the leaking of the sewage into his cellar. Held, that, in the absence of knowledge that the sewer was improperly constructed, the owner of the land might well assume that it was tight, and due care on his part did not require him to guard against a defective construction of the sewer, the existence of which he had no reason to suspect.

The duty of keeping a sewer in repair rests upon the city, and if it is necessary, in order to prevent the leaking of sewage from the sewer into the cellar of abutting premises, to change the location of the sewer to another part of the street, it may be done by the city through its superintendent of sewers without the order of the board of mayor and aldermen, and the city will not be excused for a negligent omission to make the sewer safe merely on the ground that the power to fix its location and to prescribe a plan for its construction rests with the board of aldermen, when that board has not exercised that power.

The liability of a city for damages caused by the leaking of sewage from a sewer constructed by it in the highway into the cellar of an abutting owner does not depend upon the assessment of the abutting owner for the cost of the sewer, but upon the injury done to him by the nuisance, and the fact that his premises are not connected with the sewer does not prevent him from recovering for the damages sustained by its negligent construction or maintenance.

In an action for injuries caused by the leaking of sewage into the plaintiff's cellar, damages for the injury to his health and business, where they are specially alleged, as well as the injury to his property, may be recovered.

Page 325

TORT, to recover damages for injury to the plaintiff's health and business. The writ was dated June 6, 1890. Trial in the Superior Court, before Bishop, J., who allowed a bill of exceptions, in substance as follows.

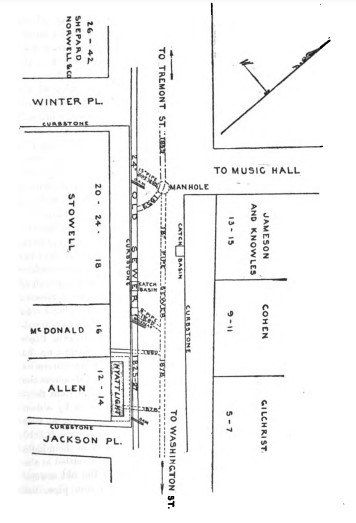

The plaintiff occupied, under a lease, a store and basement in the premises numbered 12 and 14 on Winter Street in the city of Boston. In that street there was a public drain or common sewer, twenty-four inches wide and eighteen inches deep, designated on the plan of a portion of Winter Street given on page 327 "Old Sewer, 1825-27." It was constructed - although by whom, or under what circumstances, did not appear on its westerly side toward the plaintiff's store of ordinary field stones, without cement; on the easterly side, of brick; and on the bottom, of plank.

There was also another sewer in the same street constructed in 1859 under an order of the board of aldermen of the city of Boston, [Note p325-1] designated on the plan as "1859-1859," which turned out from the old sewer just below Tremont Street and re-entered it opposite to the premises marked "Stowell" on the plan, and a third sewer, constructed under a similar order [Note p325-2] in 1878, designated

Page 326

on the plan as the "18" Pipe Sewer, 1878," connecting with the 1859 sewer at the manhole shown on the plan, and running thence past the plaintiff's premises to Washington Street. When the 1878 sewer was built, the connection between the 1859 sewer and the old sewer was discontinued. In the years 1877-78 the plaintiff's lessor, with the permission of the superintendent of streets, and in compliance with the ordinances of the city, and the regulations of the board of aldermen, extended the cellar of the premises in question, which theretofore was even with the line of the street, about seven feet under the sidewalk, so that its outer wall, which, in accordance with the regulations of the board of aldermen, was constructed of block granite and cement, came just within the outside line of the sidewalk, and within one or two feet of the westerly side of the old sewer, as shown on the plan by the dotted line on the front of the premises marked "Allen."

The cellar was also deepened, so that its floor was about two and a half feet below the level of the bottom of the old sewer, and the premises were at the same time connected with the new sewer, but never were connected with the old sewer. There was no evidence that there had been any leaking of sewage prior to 1880, but in that year the plaintiff's lessor perceived an odor coming, as was thought, from No. 16 Winter Street, and thereupon an examination was made by one Fox, who in 1874 had connected that estate by means of a drain-pipe with the old sewer. He found the drain-pipe in good order, but discovered sewage coming out of the old sewer, and percolating into the premises of the plaintiff's lessor. This was communicated to the superintendent of sewers of the city, who carried the

Page 327

Page 328

connecting drain of No. 16 Winter Street, by an Akron drainpipe, through the old sewer into the new one, and built a brick and cement bulkhead across the old sewer, as indicated on the plan, and inserted an eight-inch pipe immediately above it to turn a part of the sewage flowing in the old sewer into the new one.

On February 1, 1885, the plaintiff took possession of the premises, under a lease, and shortly thereafter bad odors were noticed in the store, and continued so that in 1886 the plaintiff complained to the mayor, and, upon an examination again made by the superintendent of sewers, sewage was found flowing into the plaintiff's cellar. The superintendent then put two courses of brick about eight inches high inside of the old sewer opposite the plaintiff's store, and later, finding this ineffectual, he pointed up the front wall of the plaintiff's store on the inside, and still later dug up the sewer at the point where the bulkhead was situated, and found the eight-inch pipe clogged with sticks, and the water backed up in the sewer, and running over the bulkhead. Thereupon he constructed a manhole directly over the bulkhead, leaving an opening of eight inches for an overflow between the top of the bulkhead and the bottom of the wall of the opening, and from time to time up to April, 1890, cleaned out the connection of the two sewers above the bulkhead. In April, 1890, on further complaint being made, the superintendent of sewers opened the old sewer between Jackson Place and the bulkhead and filled it in with gravel, bricked up the overflow between the top of the bulkhead and the bottom of the wall of the manhole, making a tight brick wall across the sewer at the bulkhead, thus preventing any sewage from flowing down into the old sewer, and closed the sewer by a dam near Jackson Place. In digging down to the old sewer at that time, it was found that the pipe connecting the estate No. 16 Winter Street with the 1878 sewer was jointed in the middle of the old sewer, and, not being supported, it had settled at the joint, and sewage was running out of it into the old sewers. He thereupon substituted for it a continuous iron pipe, but declined, though requested by the plaintiff, to fill up and discontinue the old sewer. Thereafter the smell diminished, until after a heavy rain, when it reappeared, and upon renewed complaint

Page 329

by the plaintiff, a fifteen-inch pipe was laid from the sewer near Winter Place into the 1878 sewer, and all sewage was stopped from flowing down into the old sewer by putting in a dam below Winter Place, all private drains and catch-basins were disconnected from the old sewer, which was filled in with gravel and discontinued, and were connected with the new one. Since that time no sewage or smell has appeared in the plaintiff's cellar.

An expert witness, who was admitted by the defendant to be the best expert in the country on sanitary questions, testified for the plaintiff that sewage and sewer gases were likely to percolate from the sewer through any material of which the foundation wall of the cellar could have been made, and that on account of the nearness of the sewer it would have been likely to enter the cellar, and that the practical way of remedying the trouble was either to dig up the old sewer in front and for some distance on either side of the plaintiff's premises, and connect the old sewer with the new one, as was done in June, 1890, or to put in a new sewer. He further testified that the several expedients adopted by the superintendent of sewers were not proper ways of keeping the sewage and sewer gas out of the cellar. On cross-examination he testified that he would not have tried to prevent the sewage and sewer gas from coming into the cellar by making a new foundation wall, because it would have been much less expensive to put in a new sewer; and that he did not believe it could be done.

The plaintiff introduced evidence tending to show that the smell from the sewage and sewer gases coming into the plaintiff's cellar, from February, 1885, to June, 1890, was very offensive, and that his health had been seriously impaired thereby; that he had incurred expenses for doctor's bills, and for alterations about the store, in attempts to remedy the trouble; that the health of his clerks had also been seriously impaired, and that some of them had left his employ on that account; that while they were in his employ they were made so sick by the stench that it was impossible for them properly to perform their duties, or properly to attend to the customers; and that, on account of the stench, customers had frequently left the store without buying.

Page 330

After the plaintiff had rested his case, the defendant asked the judge to rule that the action could not be maintained, which the judge declined to do, and the defendant excepted. The defendant then requested the judge to give the following rulings:

"1. The city is not liable for the injuries to the plaintiff's health. 2. The city is not liable for injury to the plaintiff's business. 3. The city is not liable for any damage. 4. If the jury find that the plaintiff, or his lessor, was guilty of negligence in extending his cellar under the sidewalk, and not so making it and its walls that sewage would not leak upon his premises, the sewer then being in the street, laid in the place and the manner described by the witnesses, (which was as above stated, and about which there was no dispute,) he cannot recover. 5. If the jury find that the only way in which the city could have prevented the injury was by removing the sewer either from the street, or to some other part of the street, they must find for the defendant. 6. If the jury find that the sewer was originally constructed in a proper and skilful manner for that period of time, (in the year 1825,) and the circumstances of the case as they were at that time, and that the city maintained the same in good condition as it was originally constructed, it is not liable to the plaintiff in this action."

The judge declined so to rule, and submitted the case to the jury under instructions, the material portions of which are as follows:

"This action of tort rests upon the alleged negligence of the city of Boston. The plaintiff claims that from January, 1885, to June, 1890, the defendant city negligently failed properly to care for and maintain a certain main drain or common sewer, and negligently allowed it to become and remain defective, leaky, and not fit to be used; by means whereof large quantities of putrid and offensive matter came into the plaintiff's premises, and created offensive odors and stenches, from which he suffered severely in his health and in his business.

"Certain facts are agreed in the case, or are not in dispute; viz. that Winter Street is a public street; that the owner of the lot occupied by the plaintiff owns to the centre of the street, and has all the rights to the centre of the street which an abutting owner, whose deed carries him to the centre of the way,

Page 331

would have, and that the plaintiff succeeds to those rights as lessee; that the sewer in Winter Street from which the trouble is alleged to have come is a public drain or common sewer maintained by the city. The authority to lay out main drains or common sewers in the city of Boston resides in the board of mayor and aldermen, who exercise the authority, not as representing the city, nor on its behalf, nor under its direction, but as public officers. The duties of the board of mayor and aldermen in laying out main drains and common sewers are of a quasi judicial nature, and involve the exercise of independent discretion, depending upon considerations affecting the public health and general convenience. It follows that the act of laying out a sewer is not the act of the city. It is the act of an independent board, and if there is a defect or want of sufficiency in the plan or system of drainage adopted, no action lies to recover for damages on account of it. .. The actual construction of a common sewer is the exercise of a merely ministerial duty, and, if not performed with reasonable care and skill, any person whose rights of property are injured by such negligence may have an action against the city. The actual construction is performed by the city itself. Also, after a common sewer is built, and until some change in its location or construction is directed by the board of mayor or aldermen, its care and maintenance devolve wholly upon the city, who provide for keeping it in order through such agents and officers as they choose to select and appoint. The sewer is the property of the city, and it is the city's duty to keep it in proper condition. This duty is ministerial, and the city is liable for negligence in its exercise to any person whom its negligence has injured.

"Before I speak of the main bearings of these two principles which I have stated, I will allude to one matter discussed in the argument. It was claimed on the one side, and denied on the other, that the city had a right to take up this sewer (the old 1825 sewer) and transfer its office and function to the other sewer built upon the other side of the street, ... and I give you this ruling upon this question.

"The system of sewerage adopted for Winter Street does not fix the location of the sewer; therefore if, to prevent sewage or sewer gases from escaping into the basement of the plaintiff's

Page 332

store, the location of the sewer should have been changed to the centre of the street, it was the duty of the city to do it, and it is liable for not having done it. The form, character, and construction of a sewer are matters for which the city is responsible. ... The continued maintenance of the sewer in a proper form, of a proper character, and in a proper condition, is a matter for which the city is responsible. A person injured, therefore, by the negligence of the city, whether it be negligence of construction or negligence of maintenance, may recover, without reference to the question whether the city has a right to take away the sewer altogether, or to transfer it under the principle which I have spoken of.

"To come then to the bearing of these propositions upon the case itself. The plaintiff's case rests upon a claim of negligence. He says that for five years the city suffered polluting matter to escape from a sewer either improperly constructed in the beginning, or allowed to be in an improper condition, or both; that the escape of the polluting matter and the condition of the sewer were with notice to the city, and that he was greatly injured by the escape of this matter caused by the condition of the sewer. .. Negligence is a breach of a duty. The city of Boston, having the duty of constructing and maintaining this sewer, owed to the plaintiff ... the duty of properly and skilfully constructing this sewer and maintaining it. ... Did the city perform this duty? The board of mayor and aldermen having the right to direct a sewer to be built, that is, to lay out a sewer, directed a sewer to be built through Winter Street, and that direction included in itself necessarily the duty on the part of the city of Boston, who were to build it, of properly and skilfully constructing it, and properly and skilfully maintaining it after it was constructed. Did the city execute the work in a skilful and proper manner, and has the city since maintained a drain the construction of which was proper and skillful? If so, the city is not responsible to the plaintiff. If it has failed in these particulars, or either of them, it is responsible to the plaintiff.

"There is a liability where the property of private persons is affected as the result of the negligent execution of the plan for the construction of a sewer, or the negligent failure to keep the

Page 333

same in repair afterwards and free from obstruction. In such a case, the city has the power to remove the cause of the trouble by substituting a skilful construction for unskilful construction, and by substituting proper maintenance for improper maintenance. Was the condition and construction of this sewer, in the beginning and subsequently, what it ought to have been? That is, was it what was proper? Was it what was skilful and reasonable to expect from the city? It is the duty of the city to use due and reasonable care under all circumstances to prevent sewage leaking from the public sewers into a person's premises. The city is not to guarantee that it will not come in; the city is not to insure that it will not come in, but it is the city's duty to use due and reasonable care under all circumstances to prevent its coming in when they undertake to construct a public sewer. If the city has performed its duty in this respect, it is exempt from liability. If it has not, it is liable, and the verdict must be for the plaintiff.

"The question whether the sewer when originally constructed was proper under all the circumstances then existing is not material, provided the city did not exercise due care in continuing to maintain it in a leaky condition subsequently. That is, if its neglect consisted in the maintenance of an improper sewer, if it was guilty of neglect at all, it is not material whether the sewer was proper in the beginning under the circumstances then existing. The fact that the officers of the sewer department acted in the matter of the removal of this trouble ... is not evidence tending to show that the city is liable, in the nature of an admission or otherwise.

" I ought to refer to the subject of the conduct of the plaintiff himself. ... A plaintiff cannot invite an injury, and then recover for it. I do not mean to indicate that there is evidence here which ought to indicate to your minds that that has been the case, but I am stating a general principle. A plaintiff in a position like the plaintiff here is bound to exercise that degree of care which would have been effective to guard him from the effects of a sewer properly constructed and maintained, and no more. He has a right to assume that the city will perform its duty, whatever that duty may be, and therefore he has a right to look for a sewer which is properly constructed and properly

Page 334

maintained, skilfully constructed and skilfully maintained. He is bound to exercise such care as would have been proper in the event of such a sewer being the sewer by which he was affected. If a sewer properly constructed and maintained overflows to the injury of a person, there is no recovery. If the city has done its duty, properly and skilfully constructed and maintained a sewer, the result is not the city's fault, and nobody can recover. If a sewer improperly constructed or maintained overflows or leaks, to the injury of a person, by reason of its improper condition, he may recover. It is not the plaintiff's duty to protect himself from sewage leaking in upon him from a sewer if its construction or condition is improper. . . . In other words, a person's duty corresponds to the requirements of a sewer properly constructed and maintained.

"The plaintiff also was bound to use due care and proper efforts to render the injury to himself as light as it could be. He was bound to use all proper exertions to get rid of it as soon as he could, and upon the evidence the plaintiff claims that he has done so; it is for you to say whether he has.

"These are the principles upon which the case is to be determined. If you find for the defendant, you will simply so return your verdict. If you find for the plaintiff, you must give to him such a sum as damages as will, in your opinion, compensate him. Not to ask yourselves what would any one of us put himself in that man's place for beforehand and go through it; that is no measure of damages.

"If the city is liable you are to give him such damages as you in your judgment say will be a fair and a proper compensation for the injuries which he has sustained in these respects:

"First. For the loss he has sustained in his business, which may be measured by the difference in the value of the store free from the odor and the value as it was during the time the odor existed. Second. For the injury to his health, and his sufferings and the pain which he has experienced, and when compensation or damages are given for impaired health the condition of the person with reference to whether or not the trouble is over, whether or not it is likely to continue, and if so, for how long, what its character is, is to be taken into account, because this is the only suit which the plaintiff can ever have for the same

Page 335

cause. Third. The expenses he has been put to on account of the matter, as, for instance, medical attendance and matters of that nature. Fourth. The injury to his business, if you find it to be so, from the persons in his employ being unable fully to perform their work, such an equivalent for their wages as you think he has suffered in that respect."

The jury returned a verdict for the plaintiff; and the defendant alleged exceptions.

The case was argued at the bar in March, 1893, and afterwards was submitted on the briefs to all the judges.

A. J. Bailey, for the defendant.

W. C. Loring & R. S. Gorham, for the plaintiff.

ALLEN, J. 1. The first objection now urged by the defendant is that the plaintiff's lessor acted in violation of law in building his cellar into the highway. This objection is untenable. There is no doubt that the general easement in the public acquired by the location of a highway extends to the limits of the highway as located. Commonwealth v. King, 13 Met. 115, 119. The right of the public includes various underground uses, of which the construction of sewers is one. Boston v. Richardson, 13 Allen 146, 159, 160. But the owner of the land over which a highway is laid retains his right in the soil for all purposes which are consistent with the full enjoyment of the easement acquired by the public. Tucker v. Tower, 9 Pick. 109. Denniston v. Clark, 125 Mass. 216. This right of the owner may grow less and less as the public needs increase. But at all times he retains all that is not needed for public uses, subject, however, to municipal or police regulations. 3 Kent Com. 433; Dillon, Mun. Corp. (4th ed.) §§ 656 b, 699, 700. The plaintiff's lessor, therefore, had a right to excavate under the sidewalk, if he thereby did not violate any ordinances or regulations of the city. It appears affirmatively that he did not. He interfered with no existing public use of the street. He was therefore using the land as he had a right to use it. McCarthy v. Syracuse, 46 N. Y. 194. Mairs v. Manhattan Real Estate Association, 89 N. Y. 498.

2. The defendant further contends that the plaintiff's lessor was negligent in not building his cellar wall so as to keep out sewage. There is nothing to show that he had any knowledge

Page 336

that the sewer would leak. There was no evidence that there had been any leaking of sewage into the premises before, or that it was ever ascertained till 1880 that sewage from the old sewer percolated into the same. In the absence of knowledge that the sewer was improperly built, the plaintiff's lessor might well assume that it was tight, and due care on his part did not require him to guard against a defective construction of the sewer, the existence of which he had no reason to suspect. The defendant's request for instructions upon this subject was rightly refused; and there is no occasion to consider whether knowledge on his part that the sewer was out of order would show negligence, under the circumstances, and debar the plaintiff from recovering for the kinds of damages complained of in this case.

3. The defendant asked the court to instruct the jury that they must find for the defendant if the only way in which the city could have prevented the injury was by removing the sewer either from the street or to some other part of the street. We are at a loss to see, on the evidence, how it could be found by the jury that there was no other way to prevent the injury than those supposed. It would seem that a new and tight sewer might have been laid there, and all the evidence in the case so assumes. The defendant contends that the city was not at liberty to put in a new sewer, and to make it tight, because the entire jurisdiction to prescribe the manner of making it and the materials to be used in keeping it in repair was in the board of aldermen. But at no time has the board of aldermen gone so far as to prescribe in what part of the street the sewer should be laid, or how it should be built. All these matters have been left to the superintendent of sewers, who was a city officer. The city, therefore, by its officer, might put the sewer in repair in any part of the street, and might prescribe the materials for building or repairing it. The duty of keeping a sewer in repair rested on the city. Child v. Boston, 4 Allen 41, 51 , 52. Emery v. Lowell, 104 Mass. 13, 16. Murphy v. Lowell, 124 Mass. 564. Bates v. Westborough, 151 Mass. 174, 182-184. And if it was necessary to put the sewer in another part of the street, the city through its superintendent of sewers might have done it. Having the power to put the sewer where it would, the city

Page 337

could not be excused for a negligent omission to make it safe, merely on the ground that the power to fix the location and to prescribe a plan of construction rested with the board of aldermen, when the board of aldermen had not exercised that power. Child v. Boston, 4 Allen 41, 53, 54. Boston Belting Co. v. Boston, 149 Mass. 44, 46, 47.

4. The fact that the plaintiff's premises were not directly connected with the old sewer does not prevent his recovering damages sustained by him through its negligent construction or maintenance. The liability of the city to the plaintiff does not depend upon the assessment of his estate for the cost of the sewer, but upon the injury done to him by the nuisance. Stanchfield v. Newton, 142 Mass. 110, 114. Merrifield v. Worcester, 110 Mass. 216, 221. Ball v. Nye, 99 Mass. 582. McCarthy v. Syracuse, 46 N. Y. 194.

5. The defendant also argues that the only damage the plaintiff can recover, if any, would be the injury to his property; and that injury to his health or business was wrongly allowed to be included in the damages. Such damages were specially alleged, and are clearly recoverable. Hunt v. Lowell Gas Light Co. 8 Allen 169. French v. Connecticut River Lumber Co. 145 Mass. 261. In the opinion of a majority of the court the entry must be,

Exceptions overruled.

FOOTNOTES

[Note p325-1] By an ordinance of the city of Boston , adopted in 1823 , it was provided, in section 1, that all common sewers which shall hereafter be considered necessary by the mayor and aldermen, in any street or highway in which there is at present no common sewer shall be made and laid, and forever afterwards shall be kept in repair, at the expense of the city, and under the direction of the mayor and aldermen or of some person or persons by them appointed.

By section 3 it was provided "that all common sewers shall be laid as nearly as possible in the centre of the street or highway, and shall be built of brick or stone , or such other materials and of such dimensions as the mayor and aldermen shall direct. And where it is practicable, it shall always be of sufficient size to be entered and cleared without disturbing the pavement above. And before the commencement of any common sewer, it shall be the duty of the mayor and aldermen to cause the level of the street to be taken, in order to determine the proper depth, capacity, and dimensions of the common sewer proposed to be laid in such street or highway. And all those particulars, together with a plan of the same, shall be recorded in a book to be kept for that purpose; in which shall also be recorded the size and directions of the particular drains which shall from time to time be permitted to be entered into such common sewers."

[Note p325-2] By an ordinance of the city of Boston , adopted in 1876, it was provided, in section 2 , that the superintendent of sewers "shall, under the direction of the board of aldermen, take the general supervision of all common sewers, which now are, or hereafter may be, built and owned by the city, or which may be permitted to be built or opened by its authority; and he shall take charge of the building and repairs of the same, and make all contracts for the supply of labor and materials therefor."

By section 3, "All common sewers which may be considered necessary by the board of aldermen, in any street or highway, shall be laid as nearly as possible in the centre of such street or highway, and shall be built of such materials, and of such dimensions, as the said board shall direct. And where it is practicable and advisable, they shall be of a sufficient size to be entered and cleaned without disturbing the pavement above."