CHESTER J. BAILEY & another vs. AGAWAM NATIONAL BANK.

CHESTER J. BAILEY & another vs. AGAWAM NATIONAL BANK.

Easement. Deed. Equitable Restrictions. Way. Covenant, Against incumbrances. Damages.

The reservation in a deed of a right of way in the grantor over the land conveyed without the use of the word "heirs " reserves only a right during the life of the grantor.

In this Commonwealth a right of way cannot be excepted from the operation of a deed unless either the right of way or the way itself is in existence when the deed is made.

A deed by the owner of two adjoining lots of land conveying one of them contained this provision: "A passageway is to be kept open and for use in common between the two houses ten feet in width, five feet of said passageway to be furnished by said H. [the grantee] and five feet by me from land lying east of the land here conveyed." There was no passageway there before the deed was made. Held, that this provision was not a reservation nor an exception, but was a contract imposing a right in perpetuity for the benefit of adjoining lands which could be enforced in equity against any one taking with notice of it, and so created an incumbrance on the granted land. Held, also, that the clause should not be construed to limit the use of the way to the existence of the two dwelling houses then on the two lots, or for use in connection with a dwelling house, but that the way provided for was intended to be for the benefit of the two lots of land, and would not be abandoned or lost, if the dwelling house on the lot retained by the grantor was removed and that lot was cut up into back yards for houses fronting on a parallel street, although those houses were on land to which the right to use the passageway did not attach because not owned by the grantor when he made the deed.

A covenant against incumbrances in a deed, if an incumbrance exists, is broken as soon as made and the damages must be assessed as of the date of the deed.

THE following statement of the case is taken from the opinion of the court:

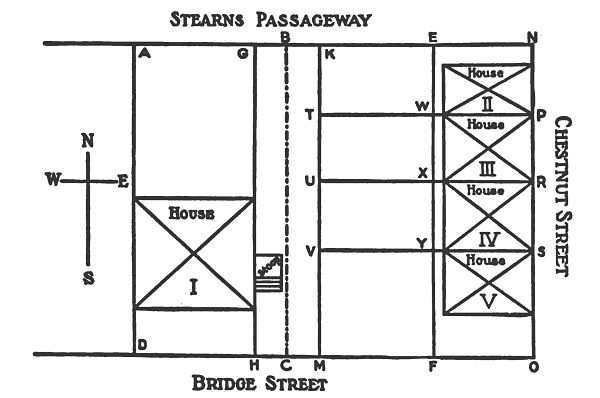

Before December, 1862, one Moore owned the parcel of land which on the plan printed on the following page is indicated by the letters A E F D. On this land were two houses, one on parcel A B C D marked I; the other, not shown on the plan, on parcel B E F C.

On December 1, 1862, Moore conveyed to one Henry in fee lot A B C D by a deed, in which, after the description of the land conveyed, is this provision : "A passageway is to be kept

Page 21

open and for use in common between the two houses ten feet in width, five feet of said passageway to be furnished by said Henry with five feet by me from land lying east of the land here conveyed. To have and to hold the aforesaid granted premises to

the said Michael Henry his heirs and assigns, to their use and behoof forever." The bill of exceptions states that "The said passageway is represented by GKMH on the plan. There was no passageway before this deed."

By mesne conveyances parcel A B C D came from Henry to the defendant and was conveyed by it to the plaintiffs by a full warranty deed dated June 15, 1892.

This action was brought for breach of the covenant against incumbrances in that deed. The breach complained of is the existence of a passageway over the five foot strip G B C H, part of the parcel A B C D conveyed to the plaintiff by the warranty deed, which right is or is in effect appurtenant to the land B E F C.

The main defence set up is that the right to a passageway in favor of lot B E F C created by this deed over the strip G B C H was a right during the life of the grantor, and that it came to an end on his death, to wit, on December 31, 1893. The case was tried by a judge of the Superior Court without a jury. The

Page 22

judge ruled that the right of lot B E F C in the passageway G K M H was a right in perpetuity, and assessed the damages as of the date of the trial. In assessing the damages the judge proceeded on the basis that "the right of way was limited in its use to the land mentioned in the deed Moore to Henry and its use could not be extended for uses in connection with lands beyond." This refers to lot E N O F, which was not owned by Moore when he conveyed to Henry in December, 1862. The defendant also contended that the right in the passageway was a "restricted right of way to be used only for purposes incident to the use and occupation of a dwelling house on the dominant estate"; that it had been abandoned; and also that "if the court finds for the plaintiffs the damages should be assessed as of the date of the delivery of the deed." The judge found for the plaintiff and assessed damages in the sum of $950, stating:

"I have assessed the damages as of the date of the trial (see Richmond v. Ames, 164 Mass. 467) and I find that the plaintiffs' estate at the date of the trial, was diminished in value in the sum of nine hundred and fifty dollars ($950) by reason of the existence of the incumbrance.

" If the damages shall be assessed as of the date of the deed from the defendant to the plaintiffs then I find the damages were four hundred and fifty dollars ($450) to which should be added interest at the rate of six per cent per annum, viz., three hundred nineteen dollars and fifty cents ($319.50) making seven hundred and sixty-nine dollars and fifty cents ($769.50) in all."

The case is here on exceptions to the refusal to rule as requested by the defendant.

The case was submitted on briefs at the sitting of the court in January, 1.905, and afterwards was submitted on briefs to all the justices.

C. H. Beckwith, for the defendant.

S. S. Taft & D. E. Tilley, for the plaintiffs.

LORING, J. [After the foregoing statement of the case.] 1. As matter of construction of the clause here in question, it was (in our opinion) the intention of the parties to it that the rights in the passageway ten feet wide, there provided for, should be rights in perpetuity, and for the benefit of the two adjoining lots of land. If this clause is to operate in favor of the grantor

Page 23

Moore by way of reservation or exception, this intention fails, so far as half the passageway, to wit, lot G B C H is concerned, for lack of the word "heirs." If it is to operate by way of reservation, that is to say, by implied grant by the grantee to the grantor, the word "heirs" is necessary. Ashcroft v. Eastern Railroad, 126 Mass. 196. It cannot operate under the Massachusetts doctrine by way of exception, because it is a new way not existing in law or in fact (that is to say, physically on the ground) at the date of the conveyance. Simpson v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 176 Mass. 359, and cases there cited.

But the clause in question does not purport to be a conveyance by way of exception or reservation; it purports to be a contract, which, as we have said, as matter of construction provides for a passageway in perpetuity for the benefit of the two adjoining lots of land. And it is a contract of which the grantee Henry's successors have taken with notice. Having taken their estate with notice of it, Henry's grantees are bound in equity to perform it. It was on this ground, (namely, that the subsequent grantee took with notice of the prior agreement imposed in perpetuity for the benefit of adjoining lands,) that the right to equitable relief by specific performance of a contract restricting the use of land in respect to the buildings to be erected on it and the use to be made of them was established when both the land benefited and that subjected to that burden had passed to grantees. Whitney v. Union Railway, 11 Gray 359. Tulk v. Moxhay, 2 Ph. 774. And see 17 Harvard Law Review, 174.

It is on its face a novel proposition that there should be a right to a passageway by way of equitable restriction over lot A in favor of lot B. But in case the owner of lot A has made an agreement in writing, but not under seal, (and for that reason not capable of being held to be a grant,) that the owner of lot B shall have a right of way over it in perpetuity, there is nothing anomalous in holding that this agreement should be specifically enforced in equity against all taking lot A with notice of that agreement in favor of the owner of the land for the benefit of which the agreement was made. In such a case it may be said and is said that there is an equitable restriction on A in favor of B. But that is apt to be misleading. The so called equitable restriction results from the fact that equity will enforce the

Page 24

agreement against those taking with notice in favor of the then owner of the land to be benefited. Equity does not enforce the agreement because there is an equitable restriction. See Whitney v. Union Railway, Tulk v. Moxhay, and Harvard Law Review, ubi supra. This perhaps was lost sight of in the opinion in Hazen v. Mathews, 184 Mass. 388.

Again, there is nothing anomalous in going into equity to enforce a right to a passageway. An injunction against obstructing it is the usual remedy invoked by the owner of a legal easement to that effect. And many an indenture under seal as to setbacks and restrictions on the kind of buildings to be erected and the use to be made of them has been held to create a legal easement although the rights under them undoubtedly are usually spoken of as equitable restrictions. For instances see Hogan v. Barry, 143 Mass. 538; Ladd v. Boston, 151 Mass. 585.

It remains to say a word of the cases in which a reservation has been held to be for life only, for lack of the word "heirs."

Claflin v. Boston & Albany Railroad, 157 Mass. 489, was an action of tort for obstructing a right of way. To maintain a way in that case it was necessary to make out a legal easement. The same however is not true of Ashcroft v. Eastern Railroad, 126 Mass. 196, or of Simpson v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 176 Mass. 359. In Simpson v. Boston & Maine Railroad there is nothing to show that the clause which was in terms a reservation in favor of the grantor was intended to be perpetual. Neither one of these two things however is true of Ashcroft v. Eastern Railroad, 126 Mass. 196. The plaintiff in that case brought a bill in equity, and the clause was "reserving to myself the right of passing and repassing, and repairing my aqueduct logs forever, through a culvert six feet wide and rising in height to the superstructure of the railroad, to be built and kept in repair by said company." We need not now determine whether that case is to be distinguished on the ground that the doctrine now laid down was not then contended for, or is to be supported on the ground that the court will not help out a conveyance defective for lack of the word "heirs" by letting it operate as an agreement. It is settled that the word "agree" may be read "grant," and an agreement under seal construed to be a grant.

Page 25

Hogan v. Barry, 143 Mass. 538. Ladd v. Boston, 151 Mass. 585. But it is another matter to hold that what is defective as a grant is valid as an agreement where the parties have undertaken to make a grant. As we have said, that need not be determined now.

If the owner of lot B E F C has a right in perpetuity specifically to enforce in equity the agreement that the strip G B C H shall be kept open as a passageway for the use of that lot, there is as much an incumbrance on the strip G B C H as there would be in case the owner of lot B E F C had a legal easement over the strip G B C H as appurtenant to his lot.

2. We are of opinion that the clause in question is not to be construed to limit the use of the way to the life of the two dwelling houses then on the two lots, or for use in connection with a dwelling house, but that it was intended that the way should be for the benefit of these two lots of land. For that reason it was not abandoned or lost in 1862 when the dwelling house on the lot retained by Moore was removed and that lot cut up into back yards for houses fronting on Chestnut Street, although the right of passageway could not be used in connection with the lots on Chestnut Street not owned by Moore at the date of the deed; Greene v. Canny, 137 Mass. 64; and the presiding judge was right in so ruling. But the right to use the passageway in question attached and now attaches to all the land then owned by Moore. Blood v. Millard, 172 Mass. 65.

3. We are of opinion that the defendant was right as to the date as of which the damages are to be assessed. The ruling appears to have been made on the authority of the concluding remarks of Chief Justice Field in Richmond v. Ames, 164 Mass. 467. The true rule is laid down in that case, namely: "In an action on the covenant against incumbrances, when the incumbrance is a right of way, and has not been relinquished, the damages are that amount of money which is a just compensation to the plaintiff for the real injury resulting from the incumbrance. Wetherbee v. Bennett, 2 Allen 428. The general rule is stated in Harlow v. Thomas, 15 Pick. 66, 69, as follows: 'The general rule in cases of this kind is plain and undisputed. If the covenantee has fairly extinguished the incumbrances, he ought to recover the expenses necessarily incurred in doing it.

Page 26

If they remain and consist of mortgages, attachments, and such liens on the estate conveyed as do not interfere with the enjoyment of it by the covenantee, he can recover only nominal damages. But if they are of a permanent nature, like the perpetual servitudes in this case, such as the covenantee cannot remove, he should recover a just compensation for the real injury resulting from their continuance. Prescott v. Trueman, 4 Mass. 627, 630.' See Batchelder v. Sturgis, 3 Cush. 201." See also Bronson v. Coffin, 108 Mass. 175; 3 Sedg. Damages, (8th ed.) § 972 ; Rawle, Covenants for Title, § 190, 191.

A covenant against incumbrances, if broken, is broken at the date of the deed (Jenkins v. Hopkins, 9 Pick. 543) and the damages accrue at that date. The damages (and we are here speaking of damages under a covenant against incumbrances as distinguished from the other covenants in a warranty deed) are a just compensation for the injury actually suffered at that time. What was probably meant by the concluding remarks of Chief Justice Field in Richmond v. Ames is that subsequent events may be put in evidence to show what the damages then incurred in fact were, and that in making up the amount of the verdict or finding, interest may be added to the amount so found, down to the date of the verdict or finding. It cannot be that the amount of damages is not fixed at the date of the breach but is dependent upon there being a rise or fall in the market value of the estate sold between the date of the breach and the date of the trial. Were it the rule, as it is in some jurisdictions, that a subsequent rise in value of an article of fluctuating value (see Sedg. Damages, § 512) may be considered in actions of trover, there might perhaps be some reason for the rule adopted by the judge in this case; but that is not so in this Commonwealth. Kennedy v. Whitwell, 4 Pick. 466. Stone v. Codman, 15 Pick. 297. Johnson v. Sumner, 1 Met. 172. East Tennessee Land Co. v. Leeson, 183 Mass. 37, 41.

The exception as to the measure of damages is sustained; all the other exceptions are overruled.