JOHN HAYES vs. FRANK D. WILKINS.

JOHN HAYES vs. FRANK D. WILKINS.

Agency. Master and Servant. Negligence.

A driver employed by a teamster who, after having completed his regular work for the day, is driving back to his employer's stable by a route which is not the shortest but which he chooses because the shortest route is blocked by teams, is acting within the scope of his employment, and if on the way he goes into a pool room to get some tobacco, negligently leaving the horse unhitched and unattended, and the horse runs away and injures a person lawfully on the highway, the employer of the driver is liable for the injuries thus caused.

Page 224

If a servant while driving the horse of his master within the scope of his employment negligently leaves him standing unhitched and unattended in order to enter a building upon an errand of his own, and the horse runs away and injures a person lawfully upon the highway, the negligence of the servant in leaving the horse while in his charge is the direct and proximate cause of the injury and his purpose in entering the building, which remotely caused the accident, is immaterial.

TORT for personal injuries from being knocked down by a runaway horse belonging to the defendant, at about five o'clock in the afternoon of November 21, 1902, while the plaintiff was lighting a lantern at the corner of Washington Street and Bow Street in that part of Boston called Charlestown to warn travellers of obstructions incident to the erection of a building which the plaintiff was superintending as a carpenter. Writ dated January 12, 1903.

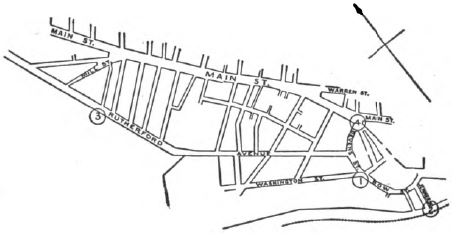

In the Superior Court the case was tried before Bishop, J. The following is a reduced copy of a plan annexed to the record.

The defendant was a truckman or teamster maintaining a stable on Front Street at the corner of Jenner Street at the point marked 2 on the plan. He ran four or five teams that year, and his business consisted in part of delivering merchandise to the Western Division of the Boston and Maine Railroad at its freight depot on Rutherford Avenue, a street shown on the plan. One Current was a driver of a team in the employ of the defendant, and on the day in question he had been directed by the defendant, or the foreman, to go to the market

Page 225

and get some cases of eggs and deliver them at the freight station. Current got the eggs and delivered them at the point marked 3 on the plan. This was his last work for the day, except to return to the stable. Instead of turning to the right and going to the stable in that direction through Rutherford Avenue, Current drove the team to the left on Rutherford Avenue to Mill Street, followed Mill Street to Main Street and went down Main Street to the corner of Main and Devens Streets, where he stopped the team at Melvin and Shaw's pool room at the point marked 4 on the plan, got off his team, and, leaving the horse unattended, went into the pool room and asked the proprietor for a piece of tobacco, and received it. While he was in the pool room the horse ran down Devens Street to the corner of Bow Street and Washington Street, and the accident occurred at the point marked 1 on the plan. These facts were not disputed.

Current testified that Rutherford Avenue was the shortest route in length, but that night it was not the shortest route "on account of so many teams coming up there it was all blocked, and the other streets were clear." He also testified that when he stopped at the pool room the horse was headed in the general direction of the stable.

There was evidence, not controverted, that the plaintiff was in the exercise of due care.

The defendant contended that Current at the time of the accident was engaged in an affair of his own, namely, getting tobacco for himself in the pool room. The plaintiff contended that Current was acting within the scope of his employment by the defendant, and also contended that the defendant was liable because he had entrusted a horse to Current which he knew or should have known was vicious and likely to run away.

At the close of the evidence, the judge ruled that the proximate cause of the accident was the fact that the horse was left unattended in a place to which Current had gone; that he had left the horse to go upon an errand of his own not connected with the business of the defendant; and that upon the authority of McCarthy v. Timmins, 178 Mass. 378, the driver of the team was not acting within the scope of his employment when he went to and into the pool room, leaving the horse unattended; and further ruled that if the defendant knew that his men previously

Page 226

had gone off on errands of their own without censure, such knowledge would not give authority to Current to repeat the act as a part of his duty to the master, or bring it within the scope of his employment, and that the evidence introduced to show that the horse was of a vicious character would not affect this conclusion.

The judge ordered a verdict for the defendant, and reported the case for determination by this court. If the rulings of the judge upon the whole evidence were right the verdict was to stand, unless the evidence offered and excluded should have been admitted and might affect the result. If the rulings upon the whole evidence were wrong, or if the judge erred in excluding the evidence of a habit of drivers to leave their horses for their own purposes with the knowledge of the defendant, the verdict was to be set aside and the case was to stand for trial.

W. A. Buie, (J. R. Murphy with him,) for the plaintiff.

W. H. Hitchcock, (W. I. Badger with him,) for the defendant.

KNOWLTON, C. J. The plaintiff was struck and injured by a horse and wagon belonging to the defendant. The horse was running away, and there was evidence from which the jury might have found that the defendant's driver was negligent in leaving the horse unhitched and unattended, knowing that it was unsafe so to leave him. It was undisputed that the plaintiff was in the exercise of due care, and the principal question is whether there was evidence that the driver was acting within the scope of his employment when he left the horse.

He was on the way to the defendant's stable, after having completed the regular work for the day by delivering some merchandise at a freight house. While the route that he took was not the shortest, it was but little longer than the other, and the jury might have found that he chose it because the other was blocked by teams, and that therefore he was within the scope of his employment up to the time when he left the horse. He went into a pool room to get some tobacco, and this movement, treated as an independent act, was not for the master's benefit, nor within the scope of his employment as a servant. But his custody of the horse, up to the time that he left him, was in the performance of the defendant's business, and any negligence in maintaining that custody was negligence for the consequences

Page 227

of which the defendant is liable. While he had the horse in custody for his master, and was charged with the duty of continuing this custody as a servant, he negligently omitted to continue it, and as a consequence the horse ran away. His purpose in going into the pool room is immaterial. His negligence occurred while he was directly engaged in his master's business, by the mere omission of that which he should have done in the business. If the attempt were to charge the master for negligence in the performance of the act of going to buy tobacco, the case would be different. If the driver had carelessly injured property in the pool room the defendant would not be liable, because his going into the pool room, considered as a positive act, was not within the scope of his employment. But the omission and failure to continue the proper custody of his horse when he had him in custody for the master, was an omission to perform his duty as a servant while he was acting for his master. This omission, quite apart from the purpose which accompanied it, was a direct and proximate cause of the plaintiff's injury.

The case is different from McCarthy v. Timmins, 178 Mass. 378, in which the driver, for his own purposes, had driven the team away from the streets on which he should have driven it for his master, and had ceased to act within the scope of his employment before the negligent omission that caused the accident.

On this part of the case we are of opinion that there was evidence for the jury. We discover no error in the other rulings at the trial

Verdict set aside.