ELIZA L. PICARD vs. ALBERT M. BEERS.

ELIZA L. PICARD vs. ALBERT M. BEERS.

Practice, Civil, Auditor's report. Evidence, Extrinsic affecting writings. Stockbroker. Statute of Frauds. Wagering Contracts. Contract, Validity.

Where, in an action at law, after the filing of the report of an auditor, the defendant moves that the report be recommitted to the auditor for correction of certain alleged errors of law in his findings, and the motion is denied, at the trial of the case it is proper for the presiding judge to allow the entire report to be put in evidence and read to the jury, it being open to the defendant to request the presiding judge to instruct the jury to disregard any findings of the auditor erroneous as matter of law if such errors appear on the face of the report.

At the trial of an action for breach of contract against one who carried on business ostensibly as a stockbroker with a central and branch offices, it appeared that the plaintiff went to a branch office and gave to an employee of the defendant an order to buy certain stock, at the same time making a specific oral agreement as to terms under which the stock was to be kept in possession of the defendant subject to the plaintiffs further orders and payment of margins. This order in the plaintiff's hearing was telephoned to the central office, and, on the receipt by the defendant's employee of a reply that the order had been filled, the plaintiff was so informed and paid to the manager of the ofiice a certain sum as margin under her oral agreement. The manager thereupon filled out and delivered to the plaintiff a printed form of ticket or contract, which was signed by no one and had no place for signatures, but purported to set out an actual purchase of stock by the plaintiff from the defendant and not through the defendant as broker. The ticket did not set out the whole of the oral agreement previously made. The defendant requested the presiding judge to rule that the ticket was a memorandum of the contract and could not be varied by extrinsic evidence. Held, that the request rightly was refused.

R. L. c. 74, § 7, providing that every contract for the sale or transfer of a share in the stock of a corporation shall be void unless at the time of the making of the

Page 420

contract the party contracting to sell or assign the same is the owner or assignee thereof or authorized by such owner or assignee so to sell or transfer, has no application to a contract with a broker for broker's services in purchasing stock.

At the trial of an action against a stockbroker for breach of a contract with the plaintiff, his customer, the defendant filed a declaration in set-off to recover certain payments made by him to the plaintiff in transactions of the nature described in R. L. c. 99, § 4, and introduced evidence tending to show settlements of such transactions by the payment of differences without any actual purchase or sale of stock, and requested the presiding judge to rule in accordance with R. L. c. 99, § 6, that such settlements were prima facie evidence that the plaintiff in set-off had an afiirmative intention that there should be no actual purchase or sale of that stock and that the defendant in set-off had reasonable cause to believe that such intention existed. It further appeared from the finding of the jury that the plaintiff in set off was acting for the defendant as her broker, and that the parties were not dealing together as principals. Held, that, in view of the finding of the jury, the ruling requested was immaterial and was refused rightly.

CONTRACT . Writ in the Municipal Court of the City of Boston dated April 8, 1905.

The first and second counts set forth claims based on contracts as to the purchase and sale of stock, and are alike except for differences in dates of transactions and names and prices of stocks and the items in the accounts annexed showing amounts paid by or to be credited to the plaintiff. They allege that the defendant was a stockbroker and that he agreed with the plaintiff to purchase for her certain stock at the then market price plus a commission, in consideration of an initial payment of a specified sum by her as margin and of payment by her of such further sums as should be necessary to protect him from loss due to fall in the market price of the stock, he to charge her with interest on the amount of the purchase price of the stock and to credit her with dividends paid on it, to sell at market price when directed by her to do so and to pay to her the profit on the transaction. The breach of contract alleged in each count is a failure to pay the profit after the plaintiff ordered a sale.

The third count is similar to the first and second excepting that it alleges not only that the defendant agreed to sell when directed to by the plaintiff but also that he further agreed to deliver the specified stock to the plaintiff upon three days' notice from her and upon payment of the balance due to him from her upon that stock, and that it alleges that the plaintiff, at a time

Page 421

when she owed the defendant nothing, gave the required notice and demanded the stock, but that the defendant refused to deliver it.

The defendant in his answer, besides a general denial, set up payment, release and discharge, and that the alleged contracts were illegal and void at common law and by virtue of R. L. c. 74, § 7. The question of release does not appear to have been raised at the trial.

The defendant also filed a declaration in set-off in two counts alleging that on certain specified dates the plaintiff contracted with him upon margin to buy of him, and he contracted with her upon margin to sell to her, certain securities, he intending that there should be no actual purchase or sale and she having reasonable cause to believe that such intention existed; and that on such contracts he paid her certain specified sums set out in an account annexed, which he claimed the right to recover under R. L. c. 99, §§ 4-6.

The answer to the declaration in set-off set up a general denial and payment.

In the Superior Court the case was referred to an auditor, and upon the filing of his report the defendant moved that it be recommitted, setting out specifically as the grounds of his motion certain alleged errors of law in the auditor's findings. The motion was denied, and the defendant filed no exception or appeal from the order denying that motion.

At the trial, which was before Hardy, J., the defendant moved to strike out certain findings in the auditor's report, and his motion was denied and the defendant excepted. Upon the plaintiff's offering the report in evidence, the defendant objected to allowing the portions containing these same findings to be read to the jury, but the presiding judge allowed the entire report to be read and admitted in evidence, and the defendant excepted. The alleged errors of law in the auditor's findings are included in the requests for rulings and instructions hereinafter set out.

The auditor's report contained among others the following findings of fact:

The accounts stated by the plaintiff as to the various transactions were correct.

The plaintiff was of a low grade of intelligence and imperfectly

Page 422

educated, absolutely ignorant of the business of buying and selling stocks and, before her transactions with the defendant, had never been in a broker's office.

The defendant carried on business ostensibly as a stockbroker with a central office and several branch ofiices. The plaintiff dealt in a branch ofiice of which one Emerson was manager, where he was assisted by a Mrs. Crosby. This branch ofiice was connected by telephone with the main office.

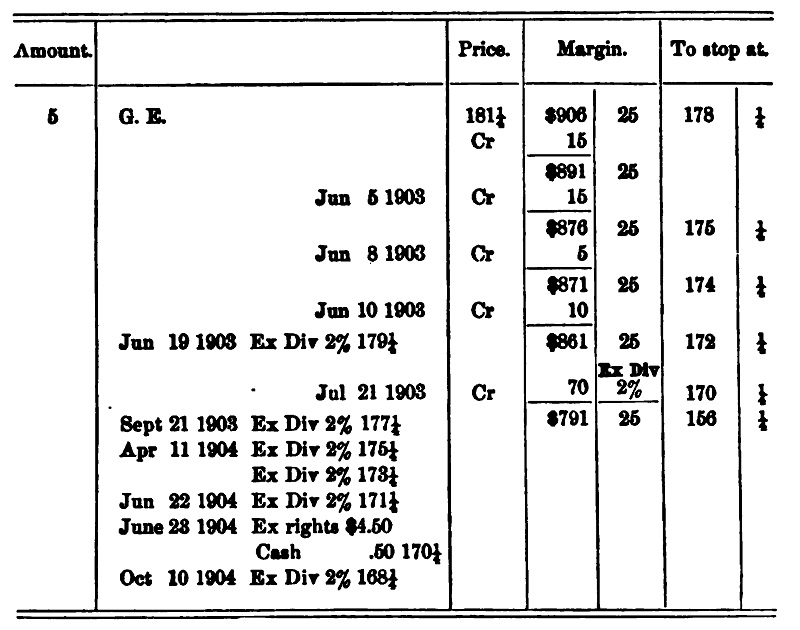

In each of the transactions in question the plaintiff gave an order to buy stock to Mrs. Crosby who filled out a printed form called a "buy slip," telephoned the particulars to the central office and, as soon as the price at which the stock was to be bought appeared on the ticker tape, again telephoned the central ofiice and inquired whether the order had been filled, and was told it was. She told this to Emerson. All this was done in the plaintiff's hearing. Emerson then filled out a printed form of ticket or contract which he delivered to the plaintiff. The plaintiff then paid the initial margin called for. Later payments of margin and receipts of dividends by the defendant were subsequently written upon the ticket or contract by Emerson. The three tickets or contracts corresponding to the three counts of the declaration were introduced in evidence respectively as Exhibits 1, 2 and 3. The forms upon which they were written were alike. The items written into the body of the tickets varied in particulars not material to the case. The following is Exhibit 1:

Established 1890. Do business with a reliable house.

(4812)

Commercial Stock Co., Bankers and Brokers.

(Page 35)

Long distance Telephones Main 3597-4 24 Congress Street.

Oxford 1379-5 128 A and 131 Tremont Street.

Night Phone, 356-3 Newton Highlands 70 Devonshire Street. Chamber of Commerce.

. . . . . . $317.50

Interest -66.00

. . . . . . =$251.50

Page 423

Boston, Jun 1 1903 (F)

Mrs. Picard

Has bought of us for his account and risk on Margin. (189 3/4)

Interest from Jun 1 1903 at 6 per cent. per annum will be charged on the purchase value of this stock.

We solicit and will receive no business except with the understanding that the actual delivery of property Bought upon orders, is in all cases contemplated and understood. Three days' notice required for the delivery of Stock.

By the agreements made between the plaintiff and Emerson and Crosby, representing the defendant, the plaintiff was to be charged with interest on the purchase price of the stock at the rate of six per cent per annum, and was to be credited with the amount of dividends and rights declared on the stock. The defendant was to hold the stock so long as the plaintiff kept up her margin and in the transactions instanced in the first and second counts of the declaration was to sell it when directed by her to do so. In the transaction mentioned in the third count of the declaration, the defendant was to hold the stock so long as

Page 424

the plaintiff kept up her margin and was to sell out when directed by her, or to deliver the stock to the plaintiff on three days' notice. In fact both purchases and sales were in all cases fictitious. No stock was ever actually bought or sold by the defendant and the transactions amounted, so far as the defendant was concerned, to wagers on the probable rise or fall in the price of the stock, with the additional element that he charged a commission to his customers on the amount of the supposed purchases and sales. The defendant fraudulently held himself out as a broker making actual purchases and sales of stock for his customers, and the plaintiff in her transactions with him was deceived by this holding out and believed him to be acting as broker for her, and believed that he was making actual purchases and sales of stock for her account. She never saw and never asked to see certificates of the stock which she believed the defendant held for her, but she once asked Emerson if the defendant really bought stock, to which Emerson replied: "Certainly, Mr. Beers buys the stock and your ticket is a voucher. The stock is held in your name."

The breaches of contracts set out in the various counts of the declaration the auditor found to have occurred as alleged.

Exhibit 10, referred to in the defendant's requests for rulings, contained the tickets or contracts relating to the transactions referred to in the declaration in set-off. Exhibit 11 contained tickets or contracts in other transactions between the plaintiff and the defendant which were introduced in evidence by the defendant to show that the plaintiff must have known the real nature of the transactions between them. The defendant introduced further evidence on this latter point at the trial, including evidence that the plaintiff made a contract with the defendant for at least one short sale of stocks upon the settlement of which he paid or credited to her on other transactions certain of the money declared for in his declaration in set-off; also that all the contracts relative to the securities set forth in the defendant's declaration in set-off were settled either by payment of differences in each or by credit to her on other transactions.

The defendant, in his first three requests for rulings, requested that the jury be instructed to disregard the findings of the auditor that the defendant owed the plaintiff under the first three

Page 425

counts of the declaration. The next eight requests were that the jury be instructed to disregard the following findings of the auditor:

(4) That the defendant contracted with the plaintiff as her broker to buy and sell for her the stocks set forth in Exhibit 10 of the auditor's report.

(5) That the plaintiff did not have reasonable cause to believe that the defendant intended at the time of contract with her relative to the several stocks set forth in his declaration in set-off and again in Exhibits 10 and 11 of the report, that there should be no actual purchase or sale. (6) That the plaintiff believed the defendant intended actually to purchase for her account the stocks specified in the declaration in set-off and again appearing in Exhibit 10 of the report.

(7) That it appeared from the testimony and the tickets or contracts, appended to the report as Exhibits 10 and 11, that the plaintiff had employed the defendant to buy and sell stocks including those specified in the declaration in set-off and also appearing in Exhibits 10 and 11 of the report.

(8) That the plaintiff believed the transactions, as to the stocks specified in the declaration in set-off, were real ones as distinguished from fictitious ones.

The presiding judge refused all of these requests and the defendant excepted.

The defendant further requested that the jury be instructed:

(9) That if the defendant was not, at the time of each of the contracts relied on by the plaintiff in her declaration, the owner or assignee of the stock contracted for or authorized by the owner or assignee thereof to sell the same, that contract was invalid under § 7 of c. 74 of R. L. and she could not recover upon such contract or for breach thereof.

(10) The papers set forth as Exhibits 1, 2 and 3 of the report are contracts between the plaintiff and the defendant wherein they contract together as principals and not as principal and broker.

(11) The papers set forth in Exhibit 10 of the report and numbered 2017 and 2035 are contracts between the plaintiff and the defendant as principals and not as principal and broker.

Page 426

(12) Aside from those numbered 2017 and 2035 the papers set forth in Exhibit 11 of the report are contracts between the plaintiff and the defendant as principals and not as principal and broker.

(13) The papers set forth as Exhibits 1, 2 and 3 of the report are memoranda of contracts between the plaintiff and defendant wherein they contract together as principals and not as principal and broker, and these contracts so far as covered by these memoranda cannot be varied by extraneous testimony.

(14) The papers set forth in Exhibit 11 of the report and numbered 2017 and 2035 are memoranda of contracts between the plaintiff and the defendant as principals and not as principal and broker, which contracts so far as covered by these memoranda cannot be varied by extraneous testimony.

(15) The papers, aside from those numbered 2017 and 2035, set forth in Exhibits 10 and 11 of the report are memoranda of contracts between the plaintiff and the defendant as principals and not as principal and broker, which contracts so far as covered by these memoranda cannot be varied by extraneous testimony.

(16) If it appear that a transaction set forth in the declaration in set-off was settled by the payment of differences and that no actual purchase or sale of the stock was made, that is prima facie evidence that the plaintiff in set-off had within §§ 4, 5 and 6 of c. 99 of R. L. an affirmative intention that there should be no actual purchase or sale of that stock, and that the defendant inset-off had reasonable cause to believe he so intended.

(17) If you find that ticket or contract numbered 4774, appearing in Exhibit 11 of the report, was settled by the decline in the market price of that stock equalling or exceeding the amount of the margin thereon, that fact is prima facie evidence that Beers intended no actual purchase or sale of that stock and that Mrs. Picard had reasonable cause to believe that such was his intention.

These requests also were refused and the defendant excepted.

The presiding judge explicitly charged the jury that, in order to find for the plaintiff either upon the declaration or upon the declaration in set-off, they must find that the defendant was acting for her as her broker. There were no exceptions to the charge to the jury. The verdict was for the plaintiff.

Page 427

F. H. Noyes for the defendant.

L. Bryant, for the plaintiff.

SHELDON, J. The court denied the defendant's motion to recommit the auditor's report, and the correctness of this action is not before us, as it was neither excepted to nor appealed from. Sullivan v. Arcand, 165 Mass. 364. Accordingly the judge at the trial properly allowed the report to be put in evidence and read to the jury. Any mistakes in ruling upon questions of law that may appear by the report to have been made by an auditor can be corrected by instructions to the jury. Allwright v. Skillings, 188 Mass. 538. Leverone v. Arancio, 179 Mass. 439. Winthrop v. Soule, 175 Mass. 400. It was of course open to the defendant to ask the court to rule that any of the auditor's findings were erroneous as matter of law, and not to allow the jury to consider such findings, if the errors appeared upon the face of the report. Briggs v. Gilman, 127 Mass. 530. Jones v. Stevens, 5 Met. 373, 377.

The defendant's main contention is that the papers or tickets which were given by his agents to the plaintiff as evidence of her several transactions with him, copies of which are set out in the bill of exceptions, were written agreements, the effect of which could not be varied by extrinsic evidence, and that these papers showed contracts of sale or purchase made directly between the plaintiff and the defendant; and accordingly that the auditor's finding that the defendant acted merely as broker, and undertook to buy and sell for her, was wrong as matter of law, and that the judge at the trial erred in submitting this question to the jury. Marks v. Metropolitan Stock Exchange, 181 Mass. 251. Anderson v. Metropolitan Stock Exchange, 191 Mass. 117, 119, 120. But it cannot be said as matter of law that these papers were written agreements within the meaning of the rule upon which the defendant relies. They were not signed by either of the parties; so far as appears by the printed exhibits, they contained no place for signatures. We do not understand either party to claim that they contain the real agreements which were made. According to the auditor's report, the contract in each case was made verbally between the customer and the defendant's agents, and the papers in question were filled out and given to the customer

Page 428

only later, after a real or pretended purchase or sale of the stock in question had been made by the defendant, and after the rights of the parties had been fixed by the verbal agreement; and the bill of exceptions does not show that this finding was controverted at the trial. But if so, the contract was made when the parties made their oral agreement; and the paper afterwards given did not as matter of law show a rescission of that agreement and the substitution of the paper as a written contract. Edgar v. Breck & Sons Corp. 172 Mass. 581, 583, and cases there cited.

In the cases relied on by the defendant, the written papers were treated by both parties as the agreements made between them. If the original contract was verbal and entire, the fact that part of it was afterwards reduced to writing does not make parol evidence inadmissible to show the whole agreement; and that question, if in dispute, must be passed upon by the jury. Ayer v. Bell Manuf. Co. 147 Mass. 46. Deshon v. Merchants' Ins. Co. 11 Met. 199. Accordingly the requests of the defendant numbered from 10 to 15 inclusive could not have been given.

For the same reasons, it would have been improper to give the defendant's ninth request. If the defendant was employed as a broker to buy stocks for the plaintiff, the provisions of R. L. c. 74, § 7, had no application. Barrett v. Hyde, 7 Gray 160. Colt v. Clapp, 127 Mass. 476, 480.

We are of opinion also that it necessarily follows from what has been said and from an examination of the auditor's report that the judge rightly refused to instruct the jury to disregard the findings of the auditor mentioned in the first eight requests of the defendant. These were all findings of fact which the auditor was warranted in making.

The defendant's sixteenth and seventeenth requests seem to us to contain correct statements of the law. R. L. c. 99, § 6. Marks v. Metropolitan Stock Exchange, 181 Mass. 251, 255. Thompson v. Brady, 182 Mass. 321. They were appropriate to the issue raised upon his declaration in set-off, and apparently might properly have been given. But it affirmatively appears by the bill of exceptions that the defendant has not been aggrieved by their refusal. Under the instructions given to the

Page 429

jury, they could not find for the plaintiff, either upon her declaration or upon the declaration in set-off, unless they found that in the matters at issue he was acting for her as her broker. Their verdicts for the plaintiff have accordingly settled that question. But this is fatal to the defendant's right of recovery upon his declaration in set-off. Lyons v. Coe, 177 Mass. 382. Accordingly, the question raised by these requests has now become immaterial. Wing v. Chesterfield, 116 Mass. 353. Kingman v. Tirrell, 11 Allen 97.

No question was saved by the exceptions or has been made before us as to the releases alleged to have been given by the plaintiff to the defendant.

Exceptions overruled.