ADELA LIZOTTE, administratrix, vs. NEW YORK CENTRAL AND HUDSON RIVER RAILROAD COMPANY.

ADELA LIZOTTE, administratrix, vs. NEW YORK CENTRAL AND HUDSON RIVER RAILROAD COMPANY.

Negligence, Employer's liability. Railroad. Evidence, Materiality. Practice, Civil, Exceptions.

In an action by an administrator against a railroad corporation for causing the death of the plaintiffs intestate while in the employ of the defendant as a section man, it appeared that the intestate had been employed for about seven years as a section man in the freight yard where the accident occurred, that the section men were supposed to look out for themselves and there was no rule or custom to give them warning of the approach of a train unless sometimes when a gang of men were working together under a foreman, that on the day of the accident the intestate was set to work alone, after a light snow storm, to clear out the switches and the interlocking system and the ditches where the switch system crossed the tracks, that while the intestate was thus at work a train went by and he stepped back to let it pass, that it went over a switch some distance beyond him, and stopped, and its rear car was detached and was pushed or kicked back upon a spur track on which a box car, with brakes set tight, was standing near the place where the plaintiff was at work, that the plaintiff knew that it was a common occurrence for a single car to be pushed down upon this spur track after cars had been drawn up the track to the switch in the way he had seen this train go, that the moving car was loaded with cinders and a brakeman was upon it, that the brakeman set his brake and tried to stop the car but was unable to do so, and the car ran into the stationary car with such force as to push it a distance of eight feet or more, and that when it stopped the intestate

Page 520

was found crushed under its wheels. Why the intestate went behind the stationary car, thus cutting off his view of the train and of the moving car, did not appear, and there was nothing to indicate whether he knew that the cinder car was approaching or that he looked out for himself in any way. The brakeman on the cinder car testified that he tried to set the brakes, beginning seasonably and using all proper effort, and was unable to stop the car. He suggested that the brake chain at the other end of the car was too long so that there was too much slack in the chain. Held, that, assuming that the defendant could have been found to be negligent on the ground that the brake of the cinder car was defective, there was no evidence that the plaintiff's intestate was in the exercise of due care at the time of the accident, when, in view of his experience and knowledge, the circumstances called for special care on his part with reference to the train which had passed and to the probability that a car would be switched back upon the spur track in the usual manner.

At the trial of an action by an administrator against a railroad corporation for causing the death of the plaintiffs intestate while in the employ of the defendant as a section man, the plaintiff cannot be allowed to show that the intestate performed his duties in a careful manner, as his habits and character are not in issue, the question in regard to his conduct being whether he exercised due care under the circumstances existing at the time of the accident.

In an action by an administrator against a railroad corporation for causing the death of the plaintiff's intestate while in the employ of the defendant as a section man, where the trial judge ordered a verdict for the defendant, if it appears that the plaintiff's intestate was not in the exercise of due care at the time of the accident, the wrongful exclusion of evidence upon the question of the defendant's negligence in providing an insufficient brake for the car which caused the death of the intestate affords no ground for sustaining an exception, as the issue is immaterial and consequently the plaintiff cannot be aggrieved by the ruling.

TORT by the administratrix of the estate of Michael Lizotte, who also was his widow, to recover for his conscious suffering and death while employed by the defendant as a section hand, alleged to have been caused by the negligence of a person in charge and control of a train of the defendant, or by a defect in a brake of a car constituting a part of the ways, works or machinery of the defendant. Writ dated March 27, 1905.

At the trial in the Superior Court, before Wait, J., the evidence for the plaintiff was introduced which is described in substance in the opinion. At the close of the plaintiffs evidence, the judge ruled that there was not sufficient evidence to warrant a finding for the plaintiff upon any count of the declaration, and ordered a verdict for the defendant. The plaintiff alleged exceptions, including exceptions to the exclusion of certain evidence offered by her.

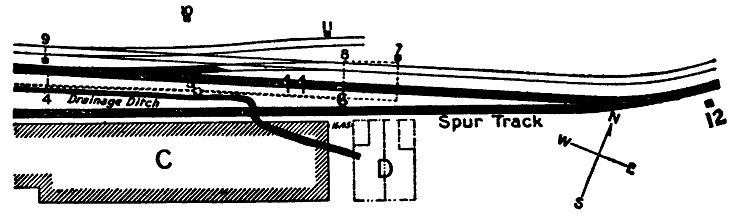

On page 521 is a reduced copy of a part of the plan which is referred to in the opinion.

Page 521

M. M. Taylor, for the plaintiff.

R. A. Stewart, for the defendant.

SHELDON, J. In our opinion the verdict for the defendant was ordered rightly. The plaintiffs intestate, Michael Lizotte, had been employed for about seven years as a section man in the Worcester yard of the defendant. His work consisted mainly in keeping the interlocking switch system, shown upon the plan which was used at the trial and at the argument before us, clear from snow and ice, keeping the drainage ditches open and doing such other work about the yard as the foreman might set him to do. He was a competent man. His eyesight and hearing were good. The section men were supposed to look out for themselves, and there was no rule or custom to give them any warning when a train came up while they were at work, except

sometimes when a gang of men were working together under a foreman or assistant foreman.

On the day that he was hurt, after or during a light snow storm he was set to work alone to clear out the switches and the interlocking system and the ditches where the switch system crossed the tracks, and had been at work in this way during the forenoon. This was his usual work, and he was accustomed to do it in his own way without any particular instructions from the foreman. Early in the afternoon he was seen at this work, near the point numbered 6 on the plan. A box car with brakes set tight was standing upon the spur track which runs past the storehouse of one Marble and the cattle pen (marked respectively C and D on the plan). This car stood about north of the cattle pen. A train of cars then passed, going easterly along track 44, which was just northerly of the spur track, and ran past Lizotte, who stepped back to let it pass. It went on over the switch numbered 12 on the plan. There this train stopped; and its rear car was detached, and was pushed or kicked back upon the

Page 522

spur track on a slightly down grade towards the car standing there. This moving car was loaded with cinders, and a brakeman was upon it. He seasonably set his brake and tried thereby to stop the car, but was unable to do so and this car ran into the stationary car with such force as to push it a distance of eight feet or more. When it stopped Lizotte was found crushed under its wheels seriously injured, and he died after a few hours of conscious suffering.

Such movements of cars and trains, including the pulling of cars up on track 44 and kicking one or more of them down on the Marble spur track, were of daily occurrence, being the usual way of putting cars on this track, as Lizotte knew. He was accustomed to work alone in this vicinity, as he was doing at the time of the accident.

The only ground upon which it is contended that the defendant could be found to have been negligent is that the brake of the car loaded with cinders was broken or defective. There is no direct evidence that this was the case; and the contention rests entirely upon the evidence of the witness Barron that he endeavored to set the brakes, beginning seasonably and using all proper effort, but that he was unable to stop the car, and upon his suggestion that the brake chain at the other end of the car was too long, so that there was too much slack in the chain. If, however, we assume that the defendant could be found to have been negligent in this respect, it was yet impossible to say that Lizotte himself was in the exercise of due care. There is absolutely no evidence of what he did after the train had passed him, or how he came to be upon the spur track and so near the stationary car when it was struck and driven against him. McCarty v. Clinton Gas Light Co. 193 Mass. 76. Gorham v. Milford, Attleborough & Woonsocket Street Railway, 189 Mass. 275. Donaldson v. New York, New Haven, & Hartford Railroad, 188 Mass. 484. When the train first passed him, he saw it and stepped out of its way. It stopped at switch number 12, only two hundred and thirty feet from him, which must have been within about a minute from its passing him. It was within his full sight; and there was nothing to prevent him from seeing it, until he apparently went voluntarily behind the stationary car and thus cut off his view. He knew that it was a common

Page 523

occurrence for a single car to be pushed down upon this spur track, after cars had been drawn up the track in the way he had just seen. It is a matter of pure conjecture whether he stepped behind the stationary car for some purpose connected with his work or entirely for his own sake, and whether or not he knew of the other car being switched back. There is nothing to help him in the circumstance that his pick and shovel were found placed in the passageway between the cattle pen and the Marble storehouse, and that his pipe lay upon the track to the east of his own body. There is nothing to indicate whether he knew that the cinder car was approaching, or that he looked out for himself in any way. For all that the evidence indicates, he may have been leaning against the stationary car or sitting upon the track and smoking, without paying any attention to the coming danger. That he previously had been doing his work in the usual way does not help him, or justify an inference that he still was attending to his duty; and the cases on which he relies are not applicable, for, in view of his experience and knowledge, the circumstances did call for special care on his part with reference to the train which had passed and to the probability that a car would be switched back upon the spur track in the usual manner. Geyette v. Fitchburg Railroad, 162 Mass. 549, 551. Tyndale v. Old Colony Railroad, 156 Mass. 503. Shea v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 154 Mass. 31. The burden is on the plaintiff to show affirmatively that her intestate was in the exercise of due care, and this she has failed to do. See beside the cases already cited, Cox v. South Shore & Boston Street Railway, 182 Mass. 497; Dacey v. New York, New Haven, & Hartford Railroad, 168 Mass. 479; Murphy v. Boston & Albany Railroad, 167 Mass. 64. The circumstances shown here differ widely from those that appeared in Meadowcroft v. New York, New Haven, & Hartford Railroad, 193 Mass. 249.

The exceptions to the exclusion of evidence may be disposed of briefly. The question whether the intestate discharged his duties in a careful manner was excluded properly. The issue was not as to his habits and character, but whether he exercised due care under the existing circumstances. Malcolm v. Fuller, 152 Mass. 160. Gahagan v. Boston & Lowell Railroad, 1 Allen 187. As to the other evidence excluded, it is enough to say that

Page 524

it bore only upon the question of the defendant's negligence in providing an insufficient brake. But as the case now stands, this was an immaterial issue, and the plaintiff was not aggrieved by the ruling made. Stackpole v. Boston Elevated Railway, 193 Mass. 562, and cases there cited.

Exceptions overruled.