SELIG LIPSKY & another vs. JACOB S. HELLER & another.

SELIG LIPSKY & another vs. JACOB S. HELLER & another.

Equity Pleading and Practice, Master's report. Easement. Way. Light and Air.

A party to a suit in equity who fails to file exceptions to a master's report in support of objections which he has filed is deemed to have accepted the report.

Where a master's report does not report the evidence a party to the suit who has filed exceptions to the report is none the less concluded by the master's findings of fact.

Where the plaintiff in a suit in equity informs the master to whom the case has been referred that he does not desire a finding on one of the matters included in his bill and the master accordingly leaves this question undecided, no objection on this ground is open to the plaintiff on exceptions to the master's report or on an appeal from a decree confirming it.

One owning land in a city divided it into five lots as shown on a plan, two of the lots and the rear portions of the others being accessible from a public street only by the use of passageways and an open space or court designated on the plan. He made separate deeds of four of the lots designating each by reference to the plan, which was recorded in the registry of deeds. The deeds of three of these lots granted a right of way in, along or over the court and passageways to a public street in common with others having a like easement or to whose estates such rights were granted as appurtenant, and in two of these deeds the open space was referred to as "a court" or "an open court." The open space was at the back of the fourth lot, and the deed of that lot described it as "subject to a right of way . . . in and over the passageway and open court, on the northerly and easterly sides appurtenant to the other estates designated on said plan." Later the same grantor sold and conveyed the fifth lot by deeds containing no effectual reference to the plan or the easement. Held, that the grantor by his deed of the fourth lot, making it subject to the right of way as described above, excepted such easement for the benefit of the fifth lot which he then owned, that being one of the "other estates designated on said plan " to which the right of way was appurtenant.

By describing land in a deed as bounding on "an open court," which belongs to the grantor, and granting a right of way "in along or over" such court and certain passageways connecting therewith, no easement of light and air over the court is created, where it does not appear that at the time of the conveyance such an easement was indispensable for the reasonable enjoyment of the land conveyed.

In a suit in equity by the respective owners of two lots of land upon a city street abutting in the rear upon an open court constituting the back portion of a lot of land belonging to the defendant fronting on the same street between the lots of the two plaintiffs, to restrain the defendant from extending his building over the open space or court in which the plaintiffs claimed rights of way and easements of light and air, it appeared that all of the lots formerly had belonged to

Page 311

the same person, who divided the land into these lots according to a plan recorded in the registry of deeds, that in the deeds the lots of the plaintiffs were bounded upon the open space described as " a court " or an "open court," that the land of the defendant was made "subject to a right of way . . . in and over the passageway and open court, on the northerly and easterly sides appurtenant to the other estates designated on said plan," that the court was connected with a public street by a passageway under the defendant's building, and that another passageway led from the other end of the court along the rear of the lot of one of the plaintiffs. There were no words in the deeds creating an easement of light and air and it did not appear that at the time of the conveyances to the plaintiffs such an easement was indispensable for the reasonable enjoyment of the land conveyed, and it was held that no such easement was created. A master to whom the case was referred found, that the use of the whole surface of the court for passage had been general and unopposed, and that such surface had been repaired at the expense of the lot owners, that no definite assignment of the location and width of the way in the court had been established by user, and that the plaintiffs were entitled to a convenient way, which he located along the northerly and easterly sides of the court, making its width the same as that of the covered passageway under the defendant's building through which access to the street was obtained. He found that if the way was so arched or built over as to correspond in height with the existing covered passageway there would be no unlawful interference with the plaintiffs' rights of way. Held, that as the words "in and over the passageway and open court on the northerly and easterly sides" were unambiguous, and as no rights had been acquired by prescription, the rights of the plaintiffs could not be extended by their unopposed use of the whole surface of the court, and that the way and the court were not commensurate in width. Held, also, that the plaintiffs could not be deprived of the access of light and air so far as these were indispensable for the proper use of a passageway of the dimensions which had been established by the master, and that the defendant must leave such openings for light and ventilation as might be found to be necessary for the convenient use of the way.

BILL IN EQUITY, filed in the Superior Court on October 24, 1905, as follows :

"And the plaintiffs say that :

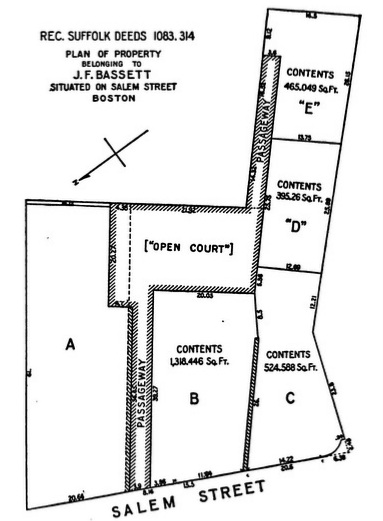

"1. The plaintiff Lipsky is the present owner of a certain parcel of land with the buildings thereon and appurtenances thereto numbered 59-61 Salem Street in said Boston, also of two parcels of land with the buildings thereon and appurtenances there to situated in the rear of 59-61 on said Salem Street being lots marked ' C,' ' D ' and ' E ' on a plan recorded with Suffolk Deeds Book 1083, page 314, a copy of which plan is hereto annexed, and the plaintiff Goldstein is the present owner of a parcel of land with the buildings thereon and appurtenances thereto numbered 65 on said Salem Street, being lot 'A' on said plan.

Page 312

"2. The defendant is the present owner of a parcel of land with the buildings thereon numbered 63 on said Salem Street being lot ' B' on said plan and that said lots A, C, D and E adjoin said lot B.

"3. In the rear of said lot ' B' there is an open court and passage-ways, one of which passage-ways leads to said Salem Street, as shown in said plan ; said court and passage-ways were laid out by one John F. Bassett who owned all of said parcels in 1871, granting the right of passage-way, drainage and other easements in and over said open court to be used and enjoyed as they now are used and enjoyed for the benefit of said adjoining estate and are a part of a common plan or design which has continued to have definite and fixed limits marked by buildings and fences, for upward of thirty (30) years and that all conveyances to date of the several parcels were made subject to said rights, privileges, easements and burdens in and over the open court of said lot ' B.'

" 4. The defendant Heller, disregarding the rights, privileges and easements of the plaintiffs, as owners of the adjoining estates, in the said open court, is about to erect an addition to the rear of his building which addition will occupy a substantial part of said open court and is to be of the dimensions appearing in an application for permit for alterations made to the building commissioner of the said City of Boston, a copy of which application is hereto annexed marked 'B.'

" 5. The plaintiffs believe and have reason to believe and say that the erection of this addition in said open court is in violation of the plaintiffs' rights, privileges and easements and will greatly diminish in value the plaintiffs' property and that they would suffer irreparable damage thereby.

" 6. [Added by amendment] That the said John F. Bassett, the plaintiffs' predecessor in title, by the use of the words 'open court' in the several deeds of conveyances intended to convey and did thereby convey an easement appurtenant to their respective estates, and that said court should remain forever open and thereby be an easement of light and air for the benefit of the granted premises.

" Wherefore the plaintiffs pray

"1. That the defendant, his agents, servants and his contractor,

Page 313

Nathan Fritz, be forever enjoined and restrained from erecting said proposed addition or any other building or structure in said open court, and that he be enjoined and restrained from interfering in any manner with the plaintiffs' proper use of the rights, easements and privileges in and over said open court, and that the defendant be ordered to preserve and keep said court in the condition heretofore existing, till the further order of the court.

"2. And for such other and further relief as the court may deem meet, in the premises."

On page 314 is a copy of the plan annexed to the bill.

The case was referred to George W. Estabrook, Esquire, as master. The material facts found by the master are stated in the opinion. The plaintiffs filed objections and exceptions to the master's report. The defendant Heller filed objections to the master's report, but filed no exceptions founded thereon.

The case was heard upon the plaintiffs' exceptions to the master's report by Richardson, J., who made a final decree that the exceptions be overruled and the master's report be confirmed, and that the plaintiffs' bill be dismissed with costs. The plaintiffs appealed.

The case was argued at the bar in March, 1908, before Knowlton, C. J., Morton, Hammond, Loring, & Braley, JJ., and afterwards was submitted on briefs to all the justices.

E. Greenhood, (I. Harris with him,) for the plaintiffs.

H. W. Bragg, (P. Pinkney with him,) for the defendants.

BRALEY, J. By a failure to take exceptions the defendant must be deemed to have accepted the master's report, and the evidence not having been reported, although the plaintiffs duly excepted, they are concluded by his findings of fact. The respective rights of the parties in the land, therefore, must be determined from the report, upon which also depends the question, whether the decree dismissing the bill should be affirmed, or wholly or partially reversed. Whitworth v. Lowell, 178 Mass. 43. French v. Peters, 177 Mass. 568, 572. East Tennessee Land Co. v. Leeson, 183 Mass. 37. In this inquiry, the plaintiffs having informed the master that they did not desire a finding as to any rights of drainage, he left this question undecided, and it is not open on their exceptions and appeal.

Page 314

The common grantor under whom all parties derive title was one John F. Bassett, who, having become seised in fee, subdivided the entire tract into lots as shown by the plan, a copy of which is annexed to the bill. The land fronted on Salem Street,

Page 315

but two of the lots and the rear portion of the others were accessible only by the use of passageways, and, exclusive of the open passageway and the space described as a " court," the whole area was covered with buildings. By separate mortgage deeds of even date and delivery he conveyed lots A, D, E and B, designating each by reference to the plan, " to be entered of record herewith." It is through a foreclosure of these mortgages that all subsequent grantees have derived title, and to ascertain the intention of the grantor they may be construed as one instrument. Cloyes v. Sweetser, 4 Cush. 403. Porter v. Sullivan, 7 Gray 441, 446. In the description of the first two, the space appearing on the plan in the rear of lot B with the connecting passageways is referred to under the designation of either a " court," or an " open court," and the grant of the first three lots expressly includes a right of way in, along or over the court and passageways to Salem Street in common with others having a like easement, or to whose estates such rights were granted as appurtenant. Having created the dominant estates, lot B is described as "subject to a right of way . . . in and over the passageway and open court on the northerly and easterly sides appurtenant to the other estates designated on said plan." It is manifest from the plan, which by reference is incorporated, and the language of the instruments, when read together, that the purpose of the grantor was to provide for the rear lands, a permanent outlet to the only public way connected with the property, either before or after the division. Boston Water Power Co. v. Boston, 127 Mass. 374, 376. Salisbury v. Andrews, 128 Mass. 336. Taft v. Emery, 174 Mass. 332. It still remains to determine whether this right was made appurtenant to lot C. After the other lots had been mortgaged, this lot was divided into three parcels, and sold at different times to the same grantee. The deeds contain no reference to either the plan or the easement, except that when conveying the last parcel the grantor and his assignee in insolvency added to the description of the premises, " together with the benefit of the reservation contained in the mortgage deed"; but in the interval his ownership of lot B had been transferred by foreclosure, and neither he nor his assignee could then subject it to an additional servitude. Greene v. Canny, 137 Mass. 64. Haverhill

Page 316

Savings Bank v. Griffin, 184 Mass. 419, 421. But, if they could not, having been delineated on the plan this lot falls within the description of "other estates" referred to in the deed of lot B, and in the master's summary of facts he finds that at the time not only was a passageway in existence, but the way as described was necessary to its enjoyment. Leonard v. Leonard, 2 Allen 543. Simpson v. Boston & Maine Railroad, 176 Mass. 359. A right of way under these conditions may become appurtenant to other lands of the grantor by either reservation or exception. In each case the character of the provision must be ascertained from his purpose and intention rather than by any particular form of words. Claflin v. Boston & Albany Railroad, 157 Mass. 489, 493. If considered a reservation, as argued by the defendant, the right of passage was limited to the life of the grantor, because of the omission of words of inheritance, and, as he has since deceased, the easement perished at his death. The means of communication, however, were intended unquestionably to be unrestricted in time so far as required for the enjoyment of the other estates, and if lot C, which had been retained by him, was deprived of this privilege, its value, either for his own use or for sale or rental, would have been greatly impaired, - a result which he could not have intended; and the perpetual right of way granted to the other lots in common also becomes by exception appurtenant to lot C. Bowen v. Connor, 6 Cush. 132, 136. Brown v. Thissell, 6 Cush. 254, 257. Dennis v. Wilson, 107 Mass. 591, 592, 594. Hogan v. Barry, 143 Mass. 538, 539. White v. New York & New England Railroad, 156 Mass. 181. Hamlin v. New York & New England Railroad, 160 Mass. 459.

The plaintiff Goldstein, who owns lot A, and the plaintiff Lipsky, who owns lots C, D and E, under mesne conveyances, have acquired as against the defendant, who has succeeded to the title of lot B, convenient rights of way over the unoccupied land shown on the plan. Boland v. St. John's Schools, 163 Mass. 229, 236, 237.

In the bill as amended the plaintiffs allege that by the use of the words " open court " Bassett intended to convey, and did convey, an easement of light and air as appurtenant to their respective estates ; but without express words a deed of land conveys no right to light and air over other lands, and the various deeds

Page 317

in the chain of title contain no express grant of such an easement. Brooks v. Reynolds, 106 Mass. 31, 32. Salisbury v. Andrews, 128 Mass. 336. Ladd v. Boston, 151 Mass. 585. Baker v. Willard, 171 Mass. 220. They further contend that by either implied grant or estoppel this right was annexed. If the grantor had said that the court was not to be built over, or was to be kept open and maintained by the abutters, as in Schwoerer v. Boylston Market Association, 99 Mass. 285, Attorney General v. Williams, 140 Mass. 329, or should always lie open as a way, as in Salisbury v. Andrews, 128 Mass. 336, 343, or its existence was shown to have been absolutely necessary to afford light and air required for the enjoyment of the surrounding premises, as in Case v. Minot, 158 Mass. 577, there would have been by implication a covenant that the entire space should remain unoccupied by buildings. Emerson v. Wiley, 10 Pick. 310. Brooks v. Reynolds, 106 Mass. 31. Case v. Minot, 158 Mass. 577, 585, and cases cited. A comparison of the boundaries in the mortgage deeds in connection with the plan, whenever the court is referred to as an abuttal, with the description of the servient estate, makes it plain, as the plaintiffs substantially concede, that Bassett retained the fee in the soil, subject to the rights which had been granted. Codman v. Evans, 1 Allen 443. Jamaica Pond Aqueduct v. Chandler, 9 Allen 159, 164. Killion v. Kelley, 120 Mass. 47. Whether an easement arises by implication depends upon the circumstances shown by the evidence as existing at the time of the grant. Salisbury v. Andrews, 19 Pick. 250, 255. This portion of the entire tract being within the boundaries of lot B, some form of reference was imperative when this space was named either as the general location of the rights of way or as an abuttal.

The burden of proof was upon the plaintiffs to show that this servitude had been created, and made appurtenant to their estates by implication. Beals v. Case, 138 Mass. 138, 140. Clapp v. Wilder, 176 Mass. 332. The master on the evidence before him found and ruled that the words " court" and " open court," being merely descriptive in the conveyancing, were not intended to create a distinct right to light and air, and as he made no finding that at the time such an easement was indispensable for the reasonable enjoyment of the estate, an implied grant after

Page 318

division cannot be raised by construction. Keats v. Hugo, 115 Mass. 204. Baker v. Willard, 171 Mass. 220, 227. Clapp v. Wilder, 176 Mass. 332, 338. It is further urged that under the rule in Salisbury v. Andrews, 19 Pick. 250, 258, the way covered the area of the court. But while the use has been general and unopposed, and the surface has been repaired at the expense of the lot owners, the right to pass and repass is described as " in and over the passageway and open court on the northerly and easterly sides," and these words being unambiguous, the way and the court were not commensurate in width. Johnson v. Kinnicutt, 2 Cush. 153. O'Brien v. Murphy, 189 Mass. 353. Because the deeds, even with the accompanying plan, did not define its width on the northerly and easterly sides, or the location and width on the southerly side, it was a question of fact as to what the parties intended as to these limits at the time of the original conveyance. George v. Cox, 114 Mass. 382. Decatur v. Walker, 137 Mass. 141. The master decided upon the evidence before him, that no definite assignment having been made by deed, or established by user, the plaintiffs were entitled to a convenient way, whose width throughout should be determined by its sufficiency to afford ample ingress and egress for the owners, and occupants of the dominant estates. George v. Cox, ubi supra. Stetson v. Curtis, 119 Mass. 266. Having reached this conclusion, and finding that no rights by prescription had been acquired, he accordingly located the way along the northerly and easterly sides, and fixed its width to correspond in breadth with the covered passageway through which communication with the street was obtained. Yet as lot C did not extend easterly far enough to abut on the way as located, he further decided, that a connecting passageway of like width was an essential part of the easement. The way as thus defined having been determined to be not only convenient, but within the terms of the easement as it existed at the date of the deeds, finally fixes the place where it is to be used and enjoyed. Atkins v. Bordman, 20 Pick. 291, 295, 296 ; S.C. 2 Met. 457.

If it is settled that the defendant's ownership of the soil confers the right to improve the property in any manner not inconsistent with the easement, the master reports, that, if built from the ground level, the proposed addition to the rear of his building

Page 319

will extend completely across the way on the southerly side of lot C. Atkins v. Bordman, 2 Met. 457. Gerrish v. Shattuck, 132 Mass. 235. Burnham v. Nevins, 144 Mass. 88. There having been no location in height except as might be required for its comfortable use, he determined, if the way was so arched or built over as to correspond in height with the exit, there would be no unlawful interference with the rights of passage, yet no reference is made to the method of construction. If not entitled to have the way kept open to the sky, the plaintiffs cannot be deprived of the access of light and air, in so far as these elements are indispensable to its use for the purposes of a passage-way of the dimensions which have been established, and the defendant must leave such openings for light and ventilation as may be found necessary for the convenience of travellers. Richardson v. Pond, 15 Gray 387, 390. Atkins v. Bordman, 2 Met. 457, 475.

It follows that so much of the decree as overrules the plaintiffs' exceptions and confirms the master's report is affirmed, but in all other particulars it must be reversed, and a decree in their favor entered, the terms of which are to be settled in the Superior Court.

Ordered accordingly.